|

Hubbell Trading Post

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER V:

TRADERS AND TRADING

According to at least one Hubbell Trading Post superintendent, it is the continuity of experienced traders who have worked there who are responsible for the success of Hubbell Trading Post since the NPS and SPMA took over. [1] Ten superintendents served at Hubbell Trading Post during its first twenty-five years as a national historic site. Although all of those men and one woman arrived in Ganado with varying degrees of experience, only one of them had ever held a superintendent's position, all the rest had a job to learn.

On the other hand, all of the three traders who have been employed at Hubbell Trading Post were already very experienced in their profession before they got there. As one of the traders mentioned, coming to work at Hubbell Trading Post was for him like "walking out the back door of the store and coming in again through the front door." [2]

The man John Cook would recruit for SPMA for the job of Trader/Manager at Hubbell Trading Post was Bill Young, a neighbor of his at Canyon de Chelly, who was then managing the Thunderbird Trading Post there.

Bill Young, SPMA's First Trader at Hubbell Trading Post, 1967-1978

Bill Young was one of the last of the truly old-time Indian Traders. He was born William S. Young in 1902 in Winslow, Arizona. His first trading post job was in 1920 at a Richardson family trading post in Leupp, Arizona (they were well-known traders). He spent the next six years at either the trading post in Leupp or the one at Cameron. He was married in 1921 to Freeda Richardson. Although only nineteen when married, Bill had been working since he was thirteen, right after his father, a railroad worker, died. In 1928, Bill bought out the Red Lake Trading Post at Tolani Lakes and traded there for fourteen years. By that time he was fluent in the Navajo language. He claimed that it took him about six months to learn "trader Navajo" but that he needed another five years to become conversationally fluent in the language.

In 1942, Bill Young moved to the Belmont Ordnance Depot (Fort Wingate, New Mexico) to be trader to the Navajo employees there, and there he remained for the next fourteen years. After a brief stint as the owner of a market in Flagstaff, Bill returned to the Navajo Nation and became trader at the Thunderbird Trading Post, Chinle, Arizona, where he remained until he accepted the position at Hubbell Trading Post. By all accounts Bill Young was a most fortunate choice. Dedicated to preserving and encouraging fine arts-and-crafts work, he continued that same long tradition of Hubbell Trading Post. Bill Young was an archetypical trader who bridged the gap from pre-World War II trading into modern times. Bill retired in 1978. He died on May 23, 1990. [3]

|

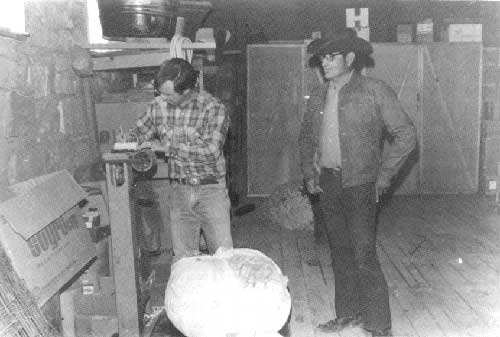

| Figure 12. Trader Bill Young examines a Navajo rug with Roberta Tso in May of 1972. Bill, one of the last of the truly old-time Indian traders, served at Hubbell Trading Post NHS from 1967-1978. NPS photo by Fred Mang, Jr. HUTR Neg. Pl-182. |

What It Takes to be an Indian Trader

While Bill Young was still trader at Hubbell Trading Post, there was already concern that a satisfactory replacement might not be available. According to the experts, [4] it just isn't possible to bring in a trainee and hope to turn him or her into a successful Indian trader. As Bill Malone said, the "charisma" might just not be present. If one is to judge by the careers of the men who have served at Hubbell Trading Post, apprenticing to become an Indian trader could take years. Unless one is a Navajo, one must learn a language with no relationship to European tongues, and one must adjust to a people who to a great extent still regard life from a different point of view than do most Americans. Although the Navajo language is becoming less of a necessity, it is still considered a requirement for the Trader/Manager at Hubbell Trading Post, and it is used there every day.

Besides having the proper charisma (an elusive attribute!), the trader must know the grocery business, and not many so-called traders these days do so. Although groceries are a small percentage of the business at Hubbell Trading Post, they are a part of any real trading post. Tourists may buy a few snacks, but Navajo who come in to trade arts and crafts will often pick up some groceries as part of the deal. They may trade a rug for some cash, pay off part of their account, and also carry out a few bags of groceries. That kind of a transaction is truly what a trading post is all about. For the trading post to keep its aura of a true trading post, it is absolutely crucial for the grocery department to be maintained; and every attempt should be made to remain competitive in the grocery business, at least in Ganado. All of the Trader/Managers at Hubbell had "thrown a lot of flour over the counter" before they came to Hubbell Trading Post.

A trader must know how to buy, sell, and trade for Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni jewelry, both old and new, expensive and not so expensive. The trader has to be able to recognize pottery, antique and modern, from most of the tribes of the Southwest. And he must be able to price old or new baskets from tribes all over the Southwest. For one person to be able to do this would seem to call for a lot of esoteric knowledge in one head. And that's exactly the case, and that's why a good trader is not created in a few months. The three men who have been Trader/Managers at Hubbell Trading Post all entered the business when they were young and all of them had spent a number of years as traders before they were hired by SPMA. Hubbell Trading Post's reputation rests on the fine quality of its arts and crafts. Many of the items there are of museum quality and some are valued in the thousands of dollars.

But Hubbell Trading Post was always famous for its Navajo rugs. Hubbell's was partly responsible for putting Indian rugs on floors all over the United States, and the "Ganado Red" is well known and easily recognizable by anybody who knows Navajo rugs and blankets. Some other rug styles originated in the area, Klagetoh, Wide Ruins, and Chinle, rug designs that say "Indian rug" to people who know little about the craft.

Hubbell Trading Post is still well known for its rugs. Rugs valued at thousands of dollars circulate through the trading post. The trader must understand the quality of a fine rug as soon as he sees it, and he must be able to discern between rugs from several parts of the Navajo

Nation as well as rugs from other tribes, or even imitation Navajo rugs. A good selection of antique rugs is also in the rug room, and the trader must know the era in which it originated, where it probably came from, and its present market value. The trader makes snap decisions involving thousands of dollars, but of course his decisions are based on decades of experience, some of it in the school of hard knocks. What the trader has to know about arts and crafts would take more space than we have here.

The trader at Hubbell Trading Post must be able to deal effectively with an extraordinarily wide range of people, customers and artists. In the very long tradition of the trading post, he is obliged to pay fair price for a job well done. Artists all across the Four Corners area know this, and many will pass by other trading posts without stopping in order to sell at Ganado. And buyers are aware that if the product is at Hubbell Trading Post it is guaranteed to be of high quality.

The old-time traders served their customers in many ways far beyond what is necessary today. To a great extent it was up to the traders to interpret the white man's world for them. Traders like J.L. Hubbell and his sons, who knew the Navajo language and understood the people and their needs, would read and write letters for them, give them advice, intercede for them in the face of legal difficulties, be their pawnbroker and banker, give them medical attention, and act as art director. And because of the Navajo attitude toward death, some traders were occasionally called upon to bury the dead.

Today, the Navajo can communicate with the white man's world just as well as can most other Americans. But if for whatever reason a Navajo does have a problem, there are tribal social agencies available to offer help and advice. However, Bill Malone mentions that at a few Navajo funerals he has been called upon to shoot the deceased's horse, so the extension of extraordinary service to the community has not ended for this particular trader. [5]

Wool and Mohair and Pinon Nuts and Livestock

All of the old-time traders bought skins and wool and mohair, and pinon nuts when available, and many of them dealt in sheep and cattle. All of this is also among the skills required of a true Indian trader, and all of the men who have been Trader/Managers at Hubbell Trading Post had or have the experience to buy and sell these commodities.

Just now there seems to be little trading going on for raw products. Reportedly the past several seasons have been too dry for pinon nuts, which in the best of times is not necessarily an annual crop (the 1991 crop was reportedly a good one). But even if there are plenty of pinon nuts available, it is apparently difficult to buy them at a low enough price in order to make money on the resale in town. The people who gather the nuts would just as soon take them to town themselves. On the other hand, it would seem that it is no longer a particularly economical venture for the Navajo to invest time and money in a pinon nut gathering expedition. In a weekend a family may gather twenty to twenty-five pounds, and that's a weekend of scrambling around on hands and knees. A few years ago the buyers tried to buy the pinon nuts at only twenty-five cents a pound, and of course at that rate the Navajo simply couldn't afford to go after them. With their recent scarcity, however, the price for pinon nuts has risen to five and six dollars a pound. And pinon nuts are a product the Navajo themselves use, so the trader does like to have some on hand in the grocery store. If they are available, some will be bought. [6]

|

| Figure 13. Loading wool to take to town. This scene was in June of 1982 when Trader Al Grieve started to buy wool. NPS photo by Theresa Nichols. HUTR Neg. R19#2. |

Hubbell Trading Post always bought wool. Travelers in the old days recall that in season the warehouse would be almost bursting with wool. Packing and weighing wool is hard work, and apparently it was always easy to lose money if the work wasn't done correctly. If he didn't know what he was doing, the trader could be cheated. And if the trader didn't have time to do all the weighing himself, he needed somebody he could trust to do the work.

When Roman Hubbell became ill, Dorothy had to cut back on the buying of wool and skins and mohair and sheep. And then, for almost ten years, she had to keep the trading post alive in hopes that the National Park Service would take over. She had quite enough to do during that period without the added work of the wool and mohair, etc. It was all she could do just to maintain the trading post as a viable business so that the NPS would have something to take over.

And, as we have noted, the Navajo Tribe is itself now dealing in many such commodities on a cooperative basis. These days, little wool is being moved by traders. For one thing, sheep and wool and skins are less a part of Navajo life than they were two or three decades ago; there isn't as much wool as there once was for a trader to buy.

|

| Figure 14. Weighing wool at Hubbell Trading Post. Trader Al Grieve with Paul Dokev in the wareroom in May, 1981. HUTR Neg. R13#31. |

Bill Young bought sheep and wool and mohair, but his dealings with these raw materials could never have been a significant part of his operation. In any case, these items cannot be separated out of his profit and loss statements on file at SPMA. Very probably Bill bought these products because he always had done so, and buying them was good for interpretive reasons, or to please Navajo customers.

What we do know for certain is that Bill Young was not buying livestock and raw products "very aggressively" when AI Grieve took over as Trader/Manager. [7] Grieve mentions that Assistant Trader/ Manager John Young (Bill Young's son) had no interest in dealing in the products, and one can imagine that Bill Young had himself gotten beyond the point where he wanted to handle them.

We know, too, that Al Grieve started buying wool and mohair. He says he bought a lot of it and did not lose any money on the deal. Well, he didn't make very much on it either, and therein lies the conflict for the Trader/Manager. Just how much time is he going to devote to a product that is not particularly profitable?

|

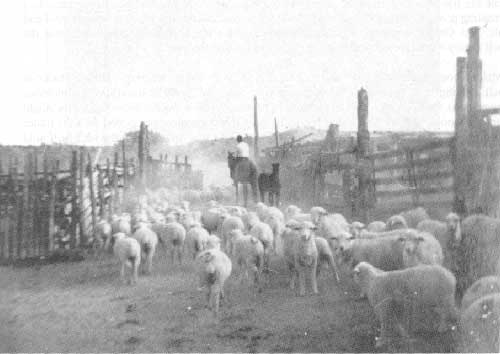

| Figure 15. Putting sheep into the corral in the evening on September 26, 1969. The horseman is Friday Kinlicheenie. NPS photo by David Brugge. Old snapshot copied by the authors. |

It does seem likely that because of modern prejudices the trading post might not---probably should not---deal in skins and livestock. Surely such an operation would be repugnant to a great many visitors no matter how accurate the scene might be. Sheep were not being purchased when Bill Malone came mainly because the corrals were in such disrepair that they wouldn't hold them and sheep have not been brought since. [8] In order to have livestock in premises, one superintendent, Kevin McKibbin, imported retired mules from the Grand Canyon. The animals deserve a retirement home, and at Hubbell they had a reason to go on living which they could do in relative luxury. Wild horses from federal lands can be removed to the trading post. There are many ways of getting livestock to Hubbell Trading Post NHS without having exploited animals there. On the other hand, wool and mohair are a part of the trading post scene that can be continued without fear of offending a lot of people.

Al Grieve started buying wool because it was something he wanted to do, trying as he did to recreate the life and times of an old-fashioned trading post. Life at a trading post, especially a farm/trading post like Hubbell's, would follow the seasons. In season, a trader bought wool and mohair. Al Grieve, together with Superintendent Juin Crosse, tried to determine what the Hubbell family would have been doing at any given time of the year. [9]

Bill Malone bought and sold wool and mohair during his first three or four years as Trader at Hubbell Trading Post. [10] He says the operation was "marginal." As he describes the business, the buyer must first contract with the source in order to get the wool. Then the trader might encounter a wool dealer who will offer the trader only five cents more per pound than the trader has paid for it. The sack may have cost the trader four or five dollars, and the sack will hold about 180 pounds, and so the profit on one sack may be only about $9.00, less the cost of the sack if he happens to lose it. But of course weighing and packing the wool takes time, and it can be a dirty business, and if the trader hires somebody to do the job for him he must pay that person at least the minimum wage. And then hope the worker is weighing the wool correctly. Once the wool is packed, it must be driven into Gallup, a further expenditure of time and money.

In the old days, Bill went on to explain, the person who was bringing in the wool might be paying off a grocery bill, and if the trader was making a profit of twenty to thirty percent on the groceries, he could make a profit on the entire deal. But most of the people in today's market who are selling wool will generally want to be paid cash for it, they won't want to take trade. So, Bill doesn't mind explaining, if you're not using the wool in a grocery account, you may lose money on it. And so he phased wool and mohair out of his operation. [11]

|

| Figure 16. Al Grieve, Trader/Manager at Hubbell Trading Post, 1978-1981. One of the NPS superintendents who was at the site during those years described At Grieve as an "outstanding" trader. The photo is from May, 1981. HUTR Neg. R13#17. |

Alan R. Grieve, Trader/Manager, 1978-1981

One ex-superintendent who was at Hubbell Trading Post when Alan Grieve was Trader/Manager there said that Al was an "outstanding" trader. [12] Grieve was the youngest of the three traders who have worked for SPMA at the trading post, and by all accounts it was he who changed the direction of the trading practices to what they are today. Those who have seen him in action say that he is a creative, imaginative trader.

Al Grieve moved to the Navajo Reservation in 1966 from his home in Albuquerque when he married a Navajo girl. By 1969 he was living in a sheep camp, herding sheep, gathering wood, hauling water. He was not, however, making very much money, and so he set out to make some by buying and selling arts and crafts, a skill he had learned while still in high school. Grieve spent his summers working for an old-time trader who would buy anything as long as he felt he could take it down the road and turn it over with a gain of a few dollars, or a trade for something he presumed to be of more value.

In 1971, Al Grieve went into business at the Standing Rock Trading Post, which he operated until 1977 with his mother as his partner. During all of that time he was learning Navajo from his customers and his wife and her family. Standing Rock was a rather typical old-time, over-the-counter trading post, which to a great extent was the reason for its demise. The Grieves were just leasing the trading post, which, like Hubbell Trading Post, had old wooden floors, wooden warerooms, and the wind and dust would seep in around the old windows. When the Public Health service insisted that the post be upgraded in order to comply with modern notions of sanitation, the Grieves decided they just did not want to go to the expense of repairing an old building that did not belong to them.

By 1978, then, Al Grieve had almost ten years experience in operating a real trading post and buying and selling Indian arts and crafts. He was fluent in Navajo. When Bill Young decided to hang up his trading boots, Al Grieve was working over in Gallup at Little Bear's Enterprises, running their pawn department, buying and selling crafts, and visiting crafts shows for them in many parts of the country. He had made many buying trips across the Indian reservations. People knew him out there where his skills were noted. One day when he was working at Little Bear's Enterprises, a National Park Service employee by the name of Art White drifted in and insisted they go to lunch, he had something important he wanted to discuss with him. That "something" turned out to be an offer to take over at Hubbell Trading Post as Trader/Manager, an offer Al Grieve accepted. [13]

Why John Young was not Chosen to Succeed his Father as Trader/Manager

John Young, Bill Young's son, went to work at Hubbell Trading Post in 1968 as assistant to his father with the approval of SPMA's Earl Jackson. Apparently it was hoped---by the Youngs---that John Young would take over as Trader/Manager when his father retired. However, even as early as 1974, when Bill Young first considered retirement, there was controversy within the Park Service and Southwest Parks and Monuments as to whether or not John would succeed to his father's position. At a May 14, 1974, meeting at the Southwest Regional Office in Santa Fe it was decided unanimously that John Young would not be acceptable as Trader/Manager of Hubbell Trading Post.

John Young's problem seems to have been one of indecisiveness. He couldn't take control, and the general opinion of him was that he lived in his father's shadow. In his later years, Bill Young would spend winter months in a warmer part of Arizona. Reportedly, John Young ran up enormous phone bills as he called Bill for advice. [14] In 1972, after Bill Young was away from the trading post for a month because of ill health, Bill admitted to Earl Jackson that it took a while for them to get back on their feet, that things had "slowed down substantially" at the shop. And at that point John Young had been on the job for about four years. Furthermore, John Young reportedly had little grasp of the Navajo language.

Although he was passed over for the Trader/Manager position when Al Grieve was hired, John Young did stay on at the trading post as an assistant. Unfortunately, resentments festered between Mr. and Mrs. Young and Al Grieve. So many problems cropped up because of the Young's presence in the store that John Young was asked to resign, with a month's pay, effective July 1, 1979. [15]

Changes in Trading Practices During Alan Grieve's Tenure as Trader/Manager

When Bill Young started as Trader at Hubbell Trading post he would generally buy low and sell high, with a two hundred or three hundred percent markup. That was how traders had operated when he entered the business in 1920, and for the most part that was how he continued to conduct business at Hubbell Trading Post. He did, however, have a fine appreciation for the arts and crafts, and his knowledge and experience sustained Hubbell Trading Post during its formative years as a national historic site. Another basic point about Bill and John Young's methods was that the men seldom went on buying trips around the Navajo Nation. Many arts and crafts people came to them, but the Youngs did not necessarily get to see all of the developments in arts and crafts, nor did they know all of the better artists and crafts people.

Al Grieve's modus operandi was to go on the road on occasional buying trips, a practice he'd followed during all of his years as a trader. As Grieve pointed out, Hubbell Trading Post is not on every crafts person's route into town, so many of them never did pass by the trading post. By going on the road, then, Grieve was able to bring a wider range of crafts into the trading post, rugs from different areas. Hopi jewelry, sand paintings from what he considered to be better sources. He would also go into Gallup to see what he could discover there, and he would go to other trading posts, carrying with him what he considered to be surplus crafts from Hubbell Trading Post and he would trade for crafts he didn't have. Ganado Red and Wide Ruins and Klagetoh rugs, which would just drift into Hubbell Trading Post, could be traded for Two Gray Hills and Teec Nos Pos rugs, only few of which would have been found in the trading post before Al Grieve got there.

So Al Grieve can be credited with expanding the variety of the arts and crafts to be found at Hubbell Trading Post. Another change in the operation of the trading post was to start paying higher prices to the artists for their work and also to have less of a markup. The rationale behind this change of business philosophy was that if the artists were paid more they would continue to bring their work to Hubbell Trading Post, and with less of a markup on the items for sale more of the crafts could be turned over. It was hoped that these changes would help perpetuate the Indian arts and crafts business, which to a great extent is what Hubbell Trading Post as a national historic site was intended to do.

This change in business philosophy worked. Business increased by over $250,000 the first two years Al Grieve was on the job. [16] However, there was no drastic change in the operation of the trading post when Al Grieve arrived to take over, just a change in emphasis in certain areas of the operation. That same can be said for the present operation. Hubbell Trading Post just tries to keep pace with the changing times, but still continue as a real trading post.

Al Grieve Resigns

Al Grieve contends that he is both a cowboy and a trader, and this conflict within himself eventually led to his resignation as Trader/Manager. He started leasing land for cattle raising even while he was at Hubbell Trading Post, and he enjoyed the work so much that he decided to go into it on a full-time basis. He leased a ranch near Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, and moved there with his family in 1981. Although he still ranches, he is also doing some trading, buying and selling arts and crafts, keeping in touch with the industry. Although he now thinks of himself as more of a cowboy than an Indian trader, he still enjoys trading.

Billy Gene Malone, Trader/Manager, 1981 to Present

Back in 1961, when Bill Malone took a job as a clerk in Al Frick's store in Lupton, Arizona, out on US 66 just west of Gallup, he had no idea that he was starting down the road of a long career as a trader. He had just been released from the Army, where he had been trained as an electronics specialist, but the clerking job in Lupton was the best he could find around Gallup. As far as he's concerned, it was probably the smartest move he ever made.

By the end of the year Bill was managing the store in Lupton, but in 1962 he took a job at the trading post at Pinon, which at that time was still an old-time, over-the-counter bullpen operation where about "999 out of 1,000" [17] of the customers were non-English-speaking Navajo. The Pinon Trading Post sold groceries on credit, bought rugs, sheep, wool, mohair, pinon nuts, took pawn, and was in most respects a classic, old-fashioned trading post. Pinon lies west of Chinle, close to the Hopi Reservation but still in Navajo country. Bill speaks Navajo; he can carry on conversations with his customers on any subject they care to choose. He is married to a Navajo woman from Lupton, and they have five children and a growing number of grandchildren.

|

| Figure 17. Bill Malone, Trader/Manager of Hubbell Trading Post NHS. Bill went to work at Hubbell Trading Post in 1981. He continues the trading post's long tradition of fair dealing and handling only quality arts and crafts. A Manchester photograph, May 9, 1991. |

In 1981 when AL Grieve was leaving Hubbell Trading Post, the ubiquitous and determined Art White stopped by the Pinon Trading Post to see if Trader Malone could be talked into applying for the position. No, Bill wasn't especially interested. He had been aware of the job back when Bill Young retired. After all, he and his family were pretty well settled in Pinon. They liked it there. But the more Bill thought about it, the more he thought that it wouldn't hurt just to drive down and take a look... Eight or ten other applicants were on hand when Bill arrived at Hubbell Trading Post. As he recalls, they were to be advised of the results of the interview in about two weeks. However, only fifteen minutes after Bill was interviewed, he was called back into the room and offered the position of Trader/Manager. By 1981, good Indian traders could have been included on the endangered species list; the people who interviewed Bill Malone would have known that.

Conflicts

One day in the spring of 1991 a young Navajo woman approached Bill Malone in the bullpen and exchanged greetings with him. She told Bill that she was taking some children on a field trip. She would need gasoline. She had some craftwork with her that she wanted to exchange for just a bit of credit. If Bill would do that for her, she could make the trip. Bill didn't hesitate.

An old-time trader would often keep a great deal of what was going on at the trading post in his head. Deals were struck suddenly, and maybe it was just too time consuming to make a record of it. Such an operation would drive a modern merchandiser mad. But of course an old-time trading post was absolutely nothing like a modern store where most of the pricing is done half a continent away, where all the sales are recorded by a computerized cash register.

There has always been a lot of give and take at a trading post. Al Grieve mentions that when he would sell an expensive rug, he might include in the deal---for free---a book on how to care for the rug. The trader is always trying to treat his customers fairly and possibly without the interference of computerized pricing and an up-to-the-minute inventory check.

It may well be that it is impossible to run a traditional trading post from downtown. The distant accountant, trying to balance his figures, is going to wonder what happened to a six-pack of Coca Cola that was given away and forgotten, a book that was thrown into a deal, a little cash exchanged for arts and crafts, the transactions not recorded because the trader was too busy to do so. The accountant has a right to know what is going on, but it may be impossible for a trader to deal in the traditional way and still be completely responsible to a distant office where modern technology is trying very efficiently to account for every penny.

This is indeed a conflict for the trader as well as the SPMA. They are working on the problem, but it does seem likely that a trading post cannot be run at long distance and that it must be operated to a great extent on old-fashioned trust if it is to maintain the aura of an old-fashioned trading post. And an old trading post was operated on guesswork, snap decisions, and personal whimsy. If Hubbell Trading Post ever enters the modern merchandising world, it may no longer be a trading post, and SPMA will no longer need a bona fide trader to run it. To what extent should Hubbell Trading Post devote itself to making money, and how much time should be devoted to "interpretation?" Buying and selling wool and mohair is hard work, time consuming, and not particularly profitable. But that's what trading posts did.

No real trading post was simply an arts-and-crafts store. Without the groceries, the trading post is no longer a trading post. And some tourist-related items are encroaching on the grocery area. It's difficult to imagine many Navajo customers being interested in Taos drums or tee shirts and caps with Hubbell Trading Post printed on them. To the objective but interested observer, the tourist items may appear out of place in the bullpen. This is a sensitive issue that probably needs some study.

Finally, Hubbell Trading Post was always a farm as well as a trading post. J.L. Hubbell spent thousands of dollars creating an irrigation system that worked. [18] When John Cook was superintendent there he saw water in every ditch. [19] Since then, because of the leaky dam, the reservoir known as Ganado Lake has been drained. Ganado Lake was the source of irrigation water on the Hubbell land. And now the ditches are dry and deteriorating, filling in with drifting sand. It will take more thousands of dollars to restore the irrigation system once the dam is repaired or replaced.

When the dam is finally repaired, and the ditches to the Hubbell land repaired, and the ditches on the historic site repaired, then farming can start up again. SPMA and the NPS can cooperate in funding this aspect of the interpretation program of Hubbell Trading Post.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

hutr/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006