|

Hubbell Trading Post

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

The cultural landscape associated with the Hubbell Trading Post complex is significant in that it comprises one of the most complete assemblages of landscape resources associated with an early Navajo trading post operation.

This landscape represents the design and development of an expanding trading post operation in Northeastern Arizona within the immediate vicinity of the Navajo Nation. While the existing Hubbell Trading Post landscape reveals the evolution of a rural vernacular landscape through a continuum of use that dates from the last quarter of the nineteenth century to the present day, the period of significance ranges from 1874 through 1967 with the primary period being defined as the period from 1874 through 1930 at which time J.L. Hubbell died and his heirs undertook full management of the trading post and associated business operations. Following J.L. Hubbell's death a variety of changes were implemented with regard to the trading post and farm landscape, however many of these changes were temporary in nature and did not alter the overall spatial organization and land use patterns originally established by J.L. Hubbell.

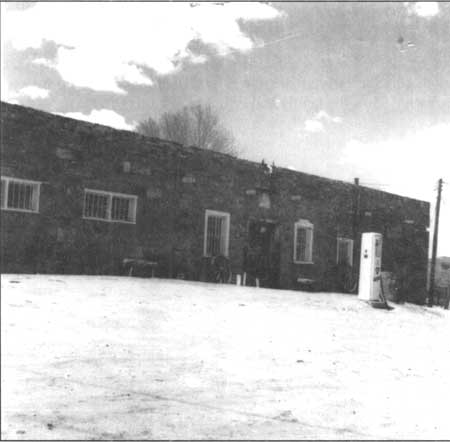

The Hubbell landscape contains numerous features that not only represent but also help define the various land use practices that have occurred over the past century. While very little information has been located to provide insight into the use of the landscape prior to the 1890's, we know that the site was first developed as a trading post location by William Leonard in or around 1874. Archival and photographic records provide us with a glimpse of the landscape design and development associated with this early trading post complex (figure 82).

Around 1878 John Lorenzo Hubbell purchased the Leonard Trading Post and within a few years had begun to modify the design of the original complex. During the 1880's Hubbell brought in a partner, a Mr. C.N. Cotton and by 1885 Cotton had acquired full ownership of the operation. In 1894 J.L. Hubbell once again purchases the trading post and operates it until his death in 1930. The trading post continued under the ownership and management of the Hubbell family until 1967 at which time the property is purchased by the National Park Service. The enacting legislation for the establishment of the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site states that the post should continue in an operational mode similar to that of an active trading post.

|

| Figure 82. Historic photograph of the Leonard buildings, pre-1913. (RP 313). |

Through its continuum of use over the past 94 years the Hubbell Trading Post and its associated landscape resources serve as a reminder of the settlement and developmental history of both the Southwestern United States and the Navajo Nation. Because of the intact nature of this cultural landscape and its varied components and associated resources it is found to be significant under National Register criteria A, B, C, and D. Criterion A applies to properties associated with events that have made significant contributions to the broad patterns of history including but not limited to exploration, settlement, farming, and ranching. Criterion B applies to properties associated with individuals whose specific contributions to history can be identified and documented. The individuals significance may be within a local, State, or National historic context. J.L. Hubbell was definitely a significant figure on the local and State level and even to some degree on the National level (particularly during the first quarter of the twentieth century). Criterion C applies to properties whose physical design reflects distinctive characteristics of a type, period or method of construction (such as late nineteenth - early twentieth century trading posts on the Navajo reservation). Criterion D applies to properties that have yielded or are likely to yield, information important to prehistory or history. Surface or subsurface remains may provide information about agricultural or industrial land uses, settlement patterns, or ceremonial traditions. [131]

PERIOD OF SIGNIFICANCE

As noted in the statement of significance described above, the period of significance has been identified as 1874 to 1967 with the primary period identified as 1874 through 1930. This period represents the continuum of use associated with the early development and evolution of the trading post operation. The Leonard period of development (1874 to 1878) is included in this primary period of significance because it laid the groundwork for Hubbell's later developments. Leonard selected the site on the Pueblo Colorado Wash and established the first layout of the trading post operation. His developments were then expanded upon by John Lorenzo Hubbell and played a significant role in Hubbell's placement of later structures and buildings including the present day trading post, the Hubbell residence, and other support structures such as the barn and corrals.

The Leonard buildings remained a dominant visual element within the trading post complex and represented a continuum of time for the evolution of the site until they were determined a safety hazard and razed by the Hubbell family in the 1920's. About this same time J.L. Hubbell's son Roman began to assist his father in the management of the farm and trading post operation and Hubbell's adult daughters returned to reside at the homestead with their families. During the next ten years a few "improvements" of an aesthetic nature were made to the landscape, primarily the area immediately adjacent to the family's residence.

The death of J.L. Hubbell in November of 1930 ended a primary period in the development and growth of the Hubbell Trading Post and farm at Ganado, Arizona and marked the beginning of a new era. Hubbell's heirs continued to modernize and mechanize the farming and business operations and the landscape associated with the residential area was clearly demarcated from the public use areas by means of a stone wall enclosure. This area of the landscape took on a more domesticated ambiance and land use areas reflected the family's desire for privacy and less of a need for total self sufficiency.

The family continued to operate the farm through the 1950's and the trading post until 1967 at which time the National Park Service took over its administration and management. With regard to the historic landscape resources, the period of significance continued until the Hubbell family left the property and turned over its operation and management to the Park Service. It is through this association with the family that the trading post and farm landscape has evolved and achieved its historical significance.

ANALYSIS OF LANDSCAPE CHARACTERISTICS

An evaluation of the landscape associated with the Hubbell trading post was conducted by examining the eleven characteristics of the cultural landscape (spatial organization, cluster arrangement, circulation, vegetation, land use, response to natural features, cultural traditions, structures, views and vistas, archeological resources, and small scale elements), identifying both historic and existing character-defining features, and determining the integrity of the resource using National Register criteria.

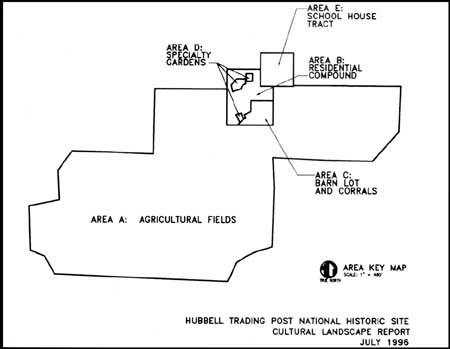

This study has examined approximately 160 acres. For the purpose of analysis and discussion the land was divided into seven definable historic land use areas. These areas include the agricultural fields and associated irrigation ditches; the residential compound; the barn lot and corral area (figure 83); the specialty garden areas (vegetable garden/flower garden); the school house/chapter house tract; Hubbell Hill outside of current park boundary; and the irrigation reservoir, main canal, and Ganado Lake and Dam all of which are outside of current park boundary (figure 84).

Each of the seven areas are discussed below with regard to their distinct historic character and specific assemblages of features that contribute to the area's significance. The discussion also covers the area's land use history as identified through research endeavors, existing conditions, and sensitivity to change. Character defining features are documented in Table 2.

|

| Figure 83. Gate in barn lot area adjacent to sheep pens, 1993. |

|

| Figure 84. Historic land use areas as defined by landscape analysis. (click on image for a enlargement in a new window) |

Table 2. Character Defining Features

| CHARACTERISTIC | FEATURE | CONTRIBUTES |

| Circulation | entry road | yes |

| field service roads | yes | |

| woodplank bridge | yes | |

| two track dirt lane | yes | |

| Dorothy Drive (into park housing_area) | no | |

| road to maintenance area | no | |

| parking area-adjacent to visitor center/admin. offices | no | |

| stiles (wooden) | yes | |

| stiles (metal) | no | |

| fruit trees along irrigation_laterals elm trees along irrigation laterals |

yes | |

| yes | ||

| cottonwood trees along field edges | yes | |

| apricot tree in courtyard | yes | |

| walnut trees in field | yes | |

| elm trees on school house tract | yes | |

| bitterberry & chokeberry in yard | yes | |

| historic shrubs-lilac, yucca, rose, etc. | yes | |

| historic vines-silver lace, VA creeper, grape, etc. | yes | |

| perennials-iris, etc. | yes | |

| Structures | Trading Post HB-l | yes |

| Hubbell Home HB-2 | yes | |

| Barn HB-3 | yes | |

| Manager's Residence HB-4 |

yes | |

| Stone Bunkhouse HB-5 | yes | |

| Guest Hogan HB-6 | yes | |

| Bread Oven HB-7 | yes | |

| Utility/Chicken House HB-8 | yes | |

| Wareroom Extension HB-9 |

yes | |

| Corrals and Sheds HB-10 | yes | |

| Hogan in Lane HB-l I | yes | |

| School/Chapter House HB-12 | yes | |

| Pumphouse - Restroom HB-13 |

yes | |

| Rootcellar/Library HB-16 | es | |

| Gazebo S-02 | yes | |

| Fire Hose Houses | no | |

| Stone Planter s-04 | yes | |

| Rock Wall (around yard) S-05 |

yes | |

| Rock Retaining Wall on School House Tract | yes | |

| Matanzas | yes | |

| Sewage Lagoon | yes | |

| Irrigation Reservoir | yes | |

| Brick BBQ | yes | |

| Irrigation Laterals & Headgates HB-19 | yes | |

| Wagon Wheel Light Fixture | yes | |

| Stone Picnic Tables/Benches | yes | |

| Small Scale Features | Stone Bird Bath | yes |

| Sundial | yes | |

| Stone Benches (trading post) | yes | |

| Wagon Wheels (trading post) | yes | |

| Plaster bas relief plaque (trading post) | yes | |

| Grinding Wheel | yes | |

| Skull over entry (trading post) | yes | |

| Ornamental Petrified Wood & Mineral Specimens | yes | |

| Ladder with Dinner Bell | yes | |

| Farm Equipment (barn lots & Sheds) | yes | |

| Wagons | yes | |

| Feed/Water Troughs | yes | |

| Gate - Iron JLH (to yard area) | yes | |

| Gate - Iron Rod (Barn) | yes | |

| Gates - Misc. Wood | yes | |

| Gates - Misc. Metal | yes | |

| Gate - Corral | yes | |

| Boneyard | yes |

Spatial Organization and Patterns of Land Use

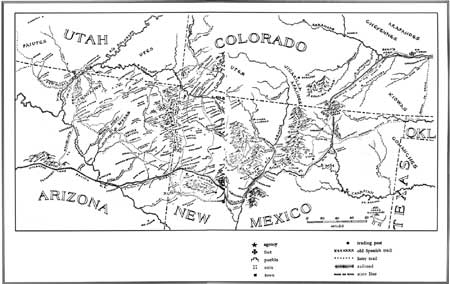

On a very large regional scale, one might look at the spatial arrangement of trading posts located within and immediately adjacent to the Navajo Reservation (figure 85). According to Adams, trading posts on the Navajo Reservation were often located approximately 20 miles apart to best serve the community and avoid undue competition between the posts. [132] One might also examine the Hubbell trading post with regard to its spatial arrangement in the context of other Hubbell family operations which included numerous trading posts, wholesale facilities, and other miscellaneous business ventures within and immediately surrounding the Navajo Reservation. A cursory examination of these relationships was made using readily available historical documentation as the majority of the region's trading posts and associated Hubbell family businesses are no longer existing. A thorough analysis of these relationships would be an excellent subject for an academic research project as would a thorough comparison of the Hubbell trading post with other posts located on the reservation. Again, a review of previous trading post studies was made in an effort to understand the overall context of the Hubbell trading post operation within the Navajo reservation but the primary focus of this study was limited to the Hubbell landscape. While some design characteristics found at Hubbell's Ganado post are highly characteristic of other posts on the reservation, the extensive agricultural operation is fairly unique. Some of the typical design characteristics are described in a later section of this report under Assessment of Resource Integrity.

Historically, the Hubbell landscape was comprised of approximately seven areas that reflect patterns of land use by the Hubbell family. These are the areas in which the Hubbells and their neighbors and associates lived, worked, and played. These areas included the agricultural fields of which there are five, and their associated irrigation features; the trading post and residential compound that includes the guest hogan, the manager's residence, the bread ovens, the chicken coop and the yard area that ties them all together; the barn lot, sheds, and corrals; the small specialty garden areas which include both the vegetable and flower garden plots; the school house/chapter house tract that now serves as the park's visitor center; the area known as Hubbell Hill is outside the park boundary; and the reservoir and associated irrigation system including the main canal and Ganado dam, all located outside of the park boundary.

The acreages of the six terraced agricultural fields are described by Peterson and included a total of about 110 acres. The easternmost field included 13 acres and was irrigated by a lateral feeding directly off of the main canal and following the western edge of the field that is also defined by a deep arroyo. This field is now occupied by the park's housing and maintenance areas. The second field is located east of the trading post and directly north of the Hubbell reservoir or holding pond and consisted of 16 acres. The field was irrigated using a lateral that fed off of the reservoir and followed the eastern edge of the field along the arroyo. The largest field area is located across the lane that leads south from the trading post and covers approximately 80 acres to the south and west of the trading post complex. This field was served by four laterals which according to Peterson were at some time or other served at least in part by the Hubbell's reservoir. [133] The first lateral runs along the eastern edge of the field and is connected to both the reservoir and the main canal. This lateral runs in a north-south direction towards the corrals and sheds and then veers west around the developed area and runs in a northwest direction towards the Pueblo Colorado Wash. The second lateral also runs in a north-south direction towards the Pueblo Colorado Wash and is fed primarily by a meandering ditch leading from the reservoir. Peterson notes that the 1931 Indian Irrigation Service map reveals that the third lateral which is now marked by a row of elm trees was served by the main canal as the Hubbell's constructed a supplementary ditch across a neighboring farm in an effort to maintain grade and bring water to the high ground along the farm's west side. [134] This lateral runs in a northwest-southeast direction. The fourth lateral was difficult to locate in the field as a result of years of wind blown sand and natural vegetation succession. The deteriorated condition of this lateral as well as barely discernible terraces reveal that over the years the family likely abandoned their attempts to keep water on the high fields of the southwest corner. [135]

Another small field area has been identified immediately west of the stone bunkhouse. This area does not appear to have been terraced but does include a small lateral irrigation ditch that runs along its eastern edge as well as a few small stone and wood headgates. The area was also enclosed by post and wire fencing along all sides. Oral histories have identified this field and noted that it was used historically by the family for the cultivation of corn. This field encompasses approximately a quarter acre of land.

Noticeable changes have occurred within two of the six terraced fields. The easternmost field has been converted into the park's housing and maintenance areas and has subsequently experienced the loss of its terraces and irrigation features. The field to the immediate west of the housing area has also been modified with regard to its overall acreage. Although historically cultivated by the Hubbells, the southern portion of this field is not within the homestead boundaries and is therefore not included within the park's boundaries. This southern area comprises approximately 5 acres. However, it should be noted that the area continues to be utilized for cultivation and provides visual continuity as a single large field from the entrance road south to the Hubbell Reservoir.

|

| Figure 85. Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni lands; adapted from McNitt (1962). Note locations and distribution of trading posts. (click on image for a enlargement in a new window) |

In 1964 there was an addition of a sewage lagoon covering approximately 1.5 acres in the north end of the big field located to the west of the corrals thereby reducing that field by a few acres. With this exception, the major changes to the westernmost fields consist of the disrepair of the historic terraces and their lack of use for cultivation activities. In general these fields have retained their approximate acreages and overall organization.

With the exception of the loss of a few structures and features the trading post and residential compound area has retained its overall spatial organization and layout as has the barn lot and corral area. One of the three specialty garden areas has retained its historical configuration while the other two have been modified over the past several years. The small vegetable garden plot located immediately south of the stone bunkhouse is intact although it is rapidly succeeding with invasive vegetation while the flower garden that historically covered the majority of the residential yard area is no longer evident with the exception of a large mass of lilacs and the border beds that follow the inside perimeter of the stone wall. The vegetable garden area located immediately south of the guest hogan has been modified with regard to its acreage and has recently lost the historical patterning of its terraces.

The spatial organization associated with the areas located outside of the park's boundaries has remained fairly constant through time. The Ganado dam was raised from 22 to 25' in height so there has been some increase in the overall size of the reservoir — it will now hold 2800 acre feet of water. No changes have occurred with regard to the layout or configuration of the main canal system, the Hubbell Reservoir, or Hubbell Hill.

There has been no substantial loss in any of the spatial elements that comprise the Hubbell Trading Post landscape although the land use activities within some of the areas have changed over time. The entire homestead acreage is in the ownership of the National Park Service and the other contiguous areas remain in the ownership of the Navajo Nation. Despite the changes that have occurred with regard to land management and use, the spatial organization of the property has retained its integrity of location, design, setting, feeling and association.

Cluster Arrangement

Within the landscape associated with the Hubbell occupation, numerous clusters have been established, These clusters may be characterized to reflect both the land use activities and the routine operations of the historic trading post and residence, Most of the clustering occurred in the vicinity of the trading post and residential compound and the barn lot and corral area (Appendix 4). The majority of the outdoor domestic activities were clustered within the residential compound and these included washing and drying of laundry, initial food preparation (both meat and vegetable), storage of fuel wood and coal, and sanitation (numerous privies were historically located west of the residence).

Three separate use areas are clustered within the area of the corrals. Pens and runs were clustered on the east side for the sheep trading operation, the main central corral was utilized by the Hubbell family for their domestic stock, and the corral and sheds on the west end were used for both storage and shelter for the family's horses and mules. On occasion the family's dairy cows were kept in the northeast corner of the sheds in a little separate corral so that the mules and slaughter cattle would not eat their feed. [136] According to Cook and Brown, the distinctions of these three operations — sheep trading, domestic stock, and the freighting business are essential chapters of the interpretive story of the Hubbell landscape. [137]

The holding pens for the sheep were divided into six or seven small pens where they could separate out the various categories of sheep for market. Each of the pens included watering and feeding troughs so the animals could be held until shipping time. The individual pens were connected by narrow alleys and small gates which led to the loading chute as well as the lane to the surrounding fields.

The surrounding barn lot area was at various times used for the freight stock, stockpiling hay and wood and other resources until further processing was possible, and the storage of various pieces of farm equipment.

With the exception of the sheep pens and corrals the historic cluster arrangements associated with this vernacular landscape are difficult to distinguish. The integrity of this particular landscape characteristic is minimal but does contribute to the overall integrity of the resource.

Circulation

The historic circulation patterns associated with the Hubbell property evolved through time and reflected changes in the economic and social development of modes of transportation in both the nation and the region. During the late nineteenth century the primary modes of transportation were pedestrian, horse-back, and horse, mule, or oxen drawn wagon. The circulation network consisted of myriad foot, horse, and informal wagon paths crisscrossing throughout the landscape. Although there were most likely a few established routes connecting the few populated areas within the area, most of the routes were informal and random (ie. the path of least resistance from point A to point B).

With the establishment of the trans-continental railroad in the 1880s, there were numerous supply depots and small communities founded south of the Navajo Reservation. The advent of these supply and shipping centers resulted in the development of a more formalized network of roads leading into and through the reservation lands. The Hubbell trading post and other similar trading operations were dependent on the movement of freight wagons from these supply centers to the remote locations of the various posts. Little information is available regarding the establishment of formal or improved road systems in this region particularly on the Navajo Reservation prior to the second quarter of the twentieth century.

During the first quarter of the 20th century J.L. Hubbell and his sons acquired automobiles for their personal use although the poor condition of the roads on the reservation made auto travel challenging if not impossible at times. For this reason the Hubbells continued to utilize freight wagons well into the 1920s. By the mid 1920s the family acquired a small fleet of freighter trucks but retained their freight wagons for use during inclement weather conditions.

According to one of Hubbell's employees and an area resident Hubbell was not concerned about the oftentimes poor condition of the roads leading to his establishment. Arthur Hubbard states:

I don't think the man Hubbell had much of idea for bringing anymore improvement than what he himself put up. By that I mean he didn't want to improve roads. It was Dr. Salisbury. Dr. Salisbury's time way after the old man was out of his political influence, past his times.

Then somebody says "we need better roads." Progress follows roads, so we need roads. He (Hubbell) was content to leave just the old wagon trails then. He never pushed for betterment of the old wagon trails. Not even flat blade of it, just leave it as it is. So another words discourage competition. So betterment of roads were not his, not anything he was interested in. He was interested in everything else, like water for giving his land in for production and the means of getting the people to come to his store to do business with him. But as for providing means of easier access for other people, non-Indians to come in and settle in. He wasn't interested in that. [138]

As mentioned earlier in this report, the main road historically ran in a north-south direction and the Pueblo Colorado Wash was forded until the first bridge was constructed in the mid 1920s by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). A 1931 photograph provides a glimpse of the bridge and the newly improved road (figure 86). This road was closed by the National Park Service in 1967 and the bridge removed. The road that serves as the park's entrance road was historically utilized by the Hubbell family and utilized one of the earliest bridges on site to cross the arroyo south of the Pueblo Colorado Wash (figure 87). The wood plank bridge that currently exists marks the location of this historic structure. The road intersects with historic Navajo Route 3, now identified as Arizona State Highway 264.

|

| Figure 86. Highway bridge crossing Pueblo Colorado Wash adjacent to Hubbell Trading Post, 1931. Photograph taken by LaCharles Eckel. |

|

| Figure 87. Hubbell grandchildren sitting on early bridge on road leading southwest away from Trading Post. (HUTR 22814). |

During the 1950s a special study noted that the "BIA has appropriated funds to improve roads on the Navajo Reservation Route 3, which is already being surfaced parallels U.S. Hwy. 66 and extends from Window Rock through Tuba City. [139] The same report further noted that there were "plans for the completion of surfacing Route 3 between 666 and U.S. 89 by 1957. This initiative for road improvements during the 1950s drastically changed circulation into and within the reservation lands.

The closure of the primary north-south route into the trading post landscape was determined essential for management purposes and included the closure of an unimproved wagon lane/field road that ran from this intersection west along the south bank of the Pueblo Colorado Wash. The alignments of these roads are still evident as are other historic field roads throughout the landscape.

The historic pedestrian paths were informal in nature and design with the exception of the concrete walks added by the Hubbell family in the immediate vicinity of the residence and the guest hogan and the flagstone walk added by the community in the vicinity of the chapter house These walks have been modified by the Park Service over the past few years. The walks around the residence have been changed from concrete to flagstone and the walk leading to the chapter house has recently been realigned to provide for both visitor safety and accessibility. Other additions or modifications with regard to pedestrian circulation on the site include the informal footpath that connects the park housing area with the administrative offices and trading post, the installation of informally and irregularly placed stepping stones in the alley between the main residence and the trading post, and the flagstone entry paving at the eastern entrance into the trading post. It should be noted that these additions are visually compatible and characteristic of the vernacular landscape and assist in providing safe access to the site.

Overall, the character-defining historic circulation patterns and associated features have retained good integrity and continue to serve as movement corridors throughout the Hubbell landscape. The orientation, layout, scale and general appearance of the vernacular landscape's circulation system continue to reflect the roads and walks used by the Hubbell family while they lived and worked at the trading post. The features associated with the Hubbell landscape circulation systems contribute to the integrity of location, design, setting, and workmanship of the site.

Vegetation

Early written accounts of the property contribute little to our knowledge and understanding of the vegetation present within the study area during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. A few early photographs which date from the 1890s provide glimpses of the land and the sparse vegetation around the trading post and residential compound (figure 88).

As mentioned earlier, with the exception of a variety of fruit trees and cultivated crops such as alfalfa, oats, rye, corn, and truck crops the Hubbells did not actively introduce vegetation into the landscape until around 1918. During the late teens and early 1920's it seems they began to plant ornamental shrubs, vines, and trees for shade.

According to the numerous interviews with Hubbells grandchildren and others who frequented the site, the variety of vegetation was noteworthy and appears to have been a characteristic visual element within the landscape. During its heyday the Hubbell landscape must have resembled a bright green oasis amidst the surrounding tans, greys, and reds of the Colorado Plateau. The extensive irrigated fields of alfalfa lined with the numerous fruit and cottonwood trees and the large vegetable gardens located east, west and south of the trading post offered a dramatic contrast to the surrounding landscape in both color and texture. As evidenced from numerous historic photographs much of the landscape immediately surrounding the trading post and residence was devoid of vegetation, probably as a result of intense grazing and trampling.

|

| Figure 88. Historic photograph of early Leonard/Hubbell Trading Post site, pre-1913, showing sparse vegetative cover. |

There were three separate areas that have been documented as vegetable garden plots and they include the terraces immediately east of the trading post, the area west of the residence and south of the guest hogan, and the area south of the stone bunkhouse. An interview with L. Hubbell Parker, Hubbell's grandson notes that "the terrace next to the road in front of the store was planted all in fruit and vegetables....squash, watermelons and other melons, corn, etc. After he (grandfather) was gone it was not used for that. The manure from the corrals was spread on that terrace and things really grew well there." [140]

The family grew quite a variety of vegetables including kale, lettuce, rhubarb, horseradish, watermelons, pumpkins, beets, carrots, banana melons, cantaloupes, cucumbers, potatoes, sweet potatoes, peanuts, and corn. Hubbell's granddaughter LaCharles Eckel reminisced: "In the summertimes when he (Hubbell) was here and we'd get up early, then we'd go out and look at the farm. If there were any cucumbers ripe, why we might have a cucumber before breakfast. If the sugarcane was ready we'd each get a section of sugarcane before breakfast. That was sort of our time together, really." [141]

According to Dorothy Hubbell, the garden area west of the yard and flower gardens was where the family planted their melons, sweet potatoes, and peanuts (at least for one year). [142] An historic photograph shows one of Hubbell's grandsons in this garden area holding a very large beet (figure 89). It seems the main vegetable garden area during J.L. Hubbell's life was immediately east of the trading post in the northwest corner of the large field and this was later moved to the garden plot south of the stone bunkhouse.

Dorothy also noted that "the main vegetable garden was back where the trailer now is (note: the vegetables where Friday's cornpatch is. We raised spinach, kale, cabbage, green beans, tomatoes and other things." [143] She continued, "we put up fruits and relish, jelly and jam, but didn't usually preserve vegetables. Pumpkins, squash, and cabbage were put in the root cellar. We would buy dried peaches from the Hopis." [144]

In addition to the vegetable garden plots mentioned above, the Hubbells also planted a cornfield that was kept fenced separately from the surrounding alfalfa fields. Dorothy references this field and identifies it as "Friday's cornpatch". This field was located immediately west of the stone bunk house and ham lot area and the southern boundary fence is still intact and readily discernible today.

|

| Figure 89. Hubbell's grandson, John L. Hubbell, holding large beet. (HUTR 4531). |

As for vegetation in the yard area, Dorothy Hubbell notes:

"When I first came, the old house (Leonard post) was out there and there was no garden (reference to flower gardens) except for some calendulas, During my first year here my mother sent me some dahlia bulbs and I planted them. When the house (Leonard post) was torn down the area was made into flower beds. We had a lot of roses, all different kinds...Roman brought slips from a friend in Gallup for the yellow roses...the castio they called it. He also brought in the yucca plants (figure 90). [145]

|

| Figure 90. Dorothy Hubbell in flower garden, around 1925. (HUTR 7111). |

She continues:

At one time we had a row of poplars just inside the wall. The roots spread out and nothing else would grow well, so we had to cut them. The lilac bushes were planted very early, but after I was here (1920). I can remember their being planted, but don't recall just when it was. The blue lilac by the little stone house was here when I came. Sais (the barnman) would cover it in the early spring with a piece of "manta" (muslin) to keep it from freezing and it bloomed every yea. We also had some pink wild roses there (in the front yard garden area). Every spring the medicine men would come in and ask to cut pieces for their uses. I would let them have a few, but tell them not to take them all.

The circular stone planter in the garden was called the "cactus bed" because at first it was planted with cactus and the yellow roses were about the outside only. Roman brought in the petrified logs. The wood vine or Virginia creeper was around the house when I came. We planted the wood vine and silver lace vines by the arbor (shade ramada). We also had two honeysuckles, one on each side of the entry to the arbor. The arbor was built over a filled in well. It was already up in 1920, just like it is now, with the silver lace vine. We called it the summer house. The picnic area was put in after I came, I don't remember when. [146]

Dorothy also mentioned in an interview that the "terrace just north of the house was always in grass" [147] but this statement has not been corroborated by other sources of documentation. Historic photographs clearly reveal that the lawn covered terrace was not installed until around 1929 although earlier photographs from the mid to late 1920's show some grass in the area (figures 91, 92, and 93). It is true that from the time of its introduction at that late date efforts have been made to maintain it as a grass covered area.

As for the trees historically found within the Hubbell landscape, numerous sources state that Hubbell and his family planted them as there were very few trees left on site once the agricultural fields were cleared of their native pinyon and juniper. The cut junipers were used for the fence posts and the small pines were used for the poles across the top of the fence to make a Kentucky style fence.

Many elder Navajo noted in interviews with park staff that there have been major changes in the Pueblo Colorado Valley with regard to vegetation and the drainages and other natural features. LaCheenie Blacksheep mentioned the dramatically increased depth of the Pueblo Colorado Wash where it runs through the Hubbell landscape. He noted that "Lok'aa (reeds) and K'aih (willows) of two types, the green ones and the gray ones" grew down through the valley along the wash. "They are all washed away now." [148] When asked "how big were the willows?" he stated "they were tall. About the height of this house. When the wash is flooded it lays them down and covers them with silt. These later grew out again thereby sort of build up the deep arroyo. That's the only way to refill these deep arroyo...there's nothing there to keep it from eroding, only sand and that's why it's hard to control these washes." [149]

|

| Figure 91. Hubbell's grandson, John L. Hubbell (Jack), with Airedale, Robin Hood. (HUTR 22828). |

|

| Figure 92. John Hubbell and "Auntie Bob" (Barbara Hubbell Goodman) in flower garden, around 1928. (HUTR 23063). |

|

| Figure 93. Monnie, Dorothy, Betty, and Jack in flower garden area in front of Hubbell home. Note lush, grassy lawn and flower gardens with summer house. (HUTR 22823). |

Soon after clearing the fields Hubbell set about planting trees. The trees included cottonwood as well as a variety of fruit and nut trees. LaCheenie Blacksheep and others noted that Hubbell planted the rows of cottonwood along the perimeter of his fields and along the irrigation ditch lines. [150] He also planted his fruit and nut trees along the ditches and field perimeters. Dorothy Hubbell mentioned that "at one time there was a row of cottonwood trees all up the lane to the south. Mr Collins cut them all out. They were cut out before I came, but I heard about it. Collins was the foreman of the farm, but later either Mr. Hubbell or Roman took charge of the farm themselves." [151] Dorothy also noted that she remembered "planting a lot of cottonwood trees in the wash. They grew into big trees and then the tribe had them all cut down in a work project one year." [152]

As a result of the introduced vegetation the Hubbell landscape took on an even greater contrast with the surrounding reservation lands. Arthur Hubbard stated:

In the springtime, around Hubbells it was really a treat to go down and around there because the pussywillows and the little pommy (?) out there would be coming out. The trees would be leaping (sic...leafing?) out. He had a lot of cottonwood trees down there. the little birds, the yellow birds would come through to migrate through in the springtime. That was the only green place, a lot of cottonwood trees and they would all come in there. The boys used to go down there to try and kill some of them for the medicine man. They sure ask for yellow bird and woodpeckers. [153]

Dorothy Hubbell also comments on this as she states:

We had all kinds of fruit trees. Mr. Hubbell bought them and planted them all along the ditches. The apricot tree in the courtyard grew from a seed that was just thrown out and we protected it. The walnut trees and the mulberry trees were already here in 1920. When I was no longer growing alfalfa (late 1950's early 1960's) I would have Friday irrigate to keep the fruit trees growing. He didn't like to do it, thought it a waste of water. [154]

During the 1930's and early 1940's new exotic trees were being introduced to the landscape as the Hubbell's followed the recommendations of the federal agricultural agencies such as the Soil Conservation Service in an effort to curb ongoing erosion of the land. These exotics included the elms and the silver-leaved poplar that were most likely introduced to the school house tract in the mid 1930s as part of the site improvement project by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). It is possible that the saltcedar and the Russian olive were also introduced to the area at this time in an effort aimed at erosion control in the Pueblo Colorado Wash. Dorothy Hubbell mentioned that Russian olive trees were planted around the barbecue pit and picnic area while she was there and this was likely in the early to mid 1940's shortly after this special outdoor use area was installed. [155] It has been estimated that the row of elms on the field embankment south of the school house/chapter house tract was planted in the early 1940's although this has not been confirmed.

Following the introduction of the exotic invasive species such as Russian olive, tamarisk, and silver-leaved poplar the landscape began to take on a new appearance and the erosion control problems in the wash continued almost unhampered. Over the past 50 years the vegetation along the wash has evolved into a dense canopy of fine textured and noticeably exotic species all but eliminating the native flora population.

Although the vegetation within the agricultural fields is reverting to a combination of native and exotic shrubs and grasses, the character of the fields remains somewhat intact as the terrace patterning and overall configurations are still readily evident. There are numerous historic plant specimens that remain throughout the landscape including apricot, apple, mulberry, plum, cottonwood, elm, and walnut trees; ornamental shrubs, vines and flowers such as the lilacs, silver lace vine, yuccas, roses, and irises; and even remnants of alfalfa in some of the field areas. These plant materials make a significant contribution to the overall integrity of the landscape with regard to location, design, materials, and feeling.

Land Use

With the early establishment of the site as a trading post operation land use activities were likely limited to the immediate area surrounding the Leonard post. Following J.L. Hubbell's acquisition of the trading post the land use area was expanded to cover a much larger area until it eventually included the 160 acres homestead and numerous acres well beyond the legal homestead boundary.

After only a few years on site Hubbell began construction of a new and larger trading post building to the south as well as several support buildings and structures. As early as 1902 he began experimenting with ways of getting water from the Pueblo Colorado Wash to irrigate crops and by 1904 had constructed a five acre reservoir south of the trading post. He then set to work to construct a small dam at the present site of the Ganado reservoir and dam and install a complex irrigation canal 2.5 miles over reservation lands to bring water to his reservoir and fields. Once he managed to get water to his fields the operation became fairly self-sufficient. Crops could be grown for both stock and family and surplus traded or sold.

The agricultural fields were established and used for crop production, the residential compound was defined and used for daily chores and associated land use activities as was the barn lot and corral area. Sites surrounding the trading post and family residence were made available for overnight lodging by customers who had come to trade and guests traveling through the area.

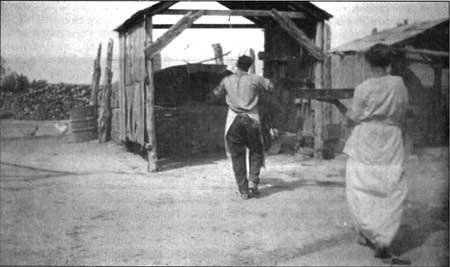

While some stock was grazed in the field areas following a cutting or harvest it seems most grazing took place beyond the homestead acreage. In fact, the family constructed and maintained corrals for cattle in an area north of the Pueblo Colorado Wash and west of Hubbell Hill. They also held several sections of land beyond the Navajo Reservation boundaries and likely used this for their stock. Cattle, sheep, and goats were butchered on site at the trading post using matanzas slaughtering rack. located in the barn lot (figures 94 and 95). Historic photographs have revealed that there were numerous matanza locations on the property with one sited just east of the south porch of the residence "but grandfather did not like it and moved (the operation) to west of the wagon shed just south of the garage." [156] Later the matanza (slaughtering rack) was moved to the north side of the wagon shed halfway between garage and barn. [157]

|

| Figure 94. Matanza (slaughtering rack) at west end of south shed being used to slaughter a cow. (RP 236). |

|

| Figure 95. Freighter's garage and Matanza (slaughtering rack) in barn lot being used to slaughter a goat, around 1931. Note large wood pile in foreground. (RP 252). |

In addition to freight stock, the family kept several horses and mules, chickens, turkeys, and pea fowl, a few dairy cows, goats, and sheep. Some of the stock was kept in the barn and the nearby sheds and corrals and the chickens, turkeys, and peafowl roamed the property. They had pigs for only a short time but found them difficult to keep.

According to family members there were several wells dug in the vicinity of the trading post and residential compound and eventually even in the area of the barn lot. At least two separate wells have been placed directly north of the trading post building, one is reported to be located under the shade ramada, there is possibly a well in the vicinity of the interior courtyard of the main residence, and one south of the barn and corrals. It seems several of these wells were abandoned as the water became slaty.

Historic photographs have documented that the family's privies were located west of the residential compound with the earliest ones shown just along the edge of the Pueblo Colorado Wash and then over time slowly moving to the south away from the wash. The wash and any conveniently deep arroyos were often used for trash and miscellaneous waste disposal (figure 96). Several accounts have noted that spoiled or damaged produce was often dumped into the main wash and even the daily ashes from the bread baking operation were dumped there. "They would dump the wheelbarrow load of ashes over the wash." [158]

As for the family burial plot, the family chose the nearby landmark known as Hubbell Hill. Along the top ridge of the hill many of the Hubbell family members have been buried including Lena Rubi, J.L. Hubbell, his friend Many Horses, Roman, Lorenzo, Adele, LaCharles Eckel, and Dorothy Hubbell.

Although at the present time the agricultural land use activities are minimal at best within the Hubbell landscape, the park staff do annually cultivate a small vegetable garden and this report proposes the future rehabilitation of the agricultural fields. The residential character of the site is retained to some degree as the manager's residence continues to be used as such by park staff and they even maintain chickens in the chicken house and a resident horse in the barn lot and corrals.

Response to Natural Features

Although no primary source documentation has been located that describes William Leonard's reasoning behind his site selection for the Leonard trading post, it is hypothesized that the post operator's response to the natural features that surrounded him played a significant role. The prominent hillock now referred to as "Hubbell Hill" might have served as an easily identifiable landmark in the landscape for site recognition. The placement of the trading post on the upper terrace of the Pueblo Colorado Wash allowed for easy access to water yet protection from high water during flash floods. The agricultural potential for the land surrounding Leonard's early trading post should have been recognized, however it does not appear that Mr. Leonard made any attempt to improve or develop this land.

On the other hand, John Lorenzo Hubbell surely recognized the potential of the land as well as the excellent location of the trading post operation. While Hubbell may have recognized the potential for agricultural development of this property at the time of his original purchase, it was approximately twenty years before he actively began to develop his farm operation. The availability of water for irrigation was essential to the development of agricultural fields and although Hubbell originally intended to use a steam operated ram-type pump to draw water from the Pueblo Colorado Wash, he later chose to select a dam site further upstream and transport the needed water resources to his farm lands via an extensive canal system.

|

| Figure 96. Ford truck chassis discarded in drainage, 1993. |

In response to the lay of the land chosen for agricultural development and its relationship to the Pueblo Colorado Wash, Hubbell decided upon using check irrigation methods. Peterson notes that Hubbell may have brought the idea with him from New Mexico or else learned of it from the irrigation books and government publications found in his library collections. [159] It should also be noted that local Navajo and Hopi farmers used variations of check irrigation as far back as Anasazi Pueblo periods and Hubbell may have borrowed the idea from them. [160] Peterson goes on to state that although furrow irrigation likely predominated in northern Arizona Hubbell "may also have deemed it prudent to go with checks because of his dependence on hired labor for irrigating." [161] The bordered terraces used for check irrigation also provided Hubbell with a way to control the degree of fall between the fields and the Pueblo Colorado Wash and avoid major erosion problems caused by water discharge.

Stone for buildings and flagstone paving was obtained locally although as the supplies diminished the workers had to travel further from the property to locate new sources. Some have hypothesized that Hubbell had his crews remove some of the stones from the prehistoric pueblo ruins on the property such as Wide Reed Ruins but Dorothy Hubbell insisted that this was not done due to Hubbell's respect for the sites and the cultural taboos associated with disturbing abandoned ruins.

In contrast to this, LaCheenie Blacksheep reveals that maybe it was not Hubbell's sensitivity to the Navajo people's beliefs but his desire to maintain a thriving business that resulted in stone from sources other than the ruins being used for building construction on site. When asked in an interview "where did the stone come from?" LaCheenie Blacksheep answered "from the hills nearby. Towards behind the trading post there are hills with lots of these rocks. We got the rocks from there." [162] The interviewer then asks, "You didn't take any stones from the Wide Reed Ruins?" And LaCheenie answered, "No, not those. It's from these hills that we got them. Anasazi ruins were forbidden by the older people. Nakai Sani (J.L. Hubbell) didn't believe in it and said we should go ahead and use these rocks from the ruins since they were already prepared. The older people wanted us to get rocks from other areas because we'd be eating from them." [163]

The flagstone used on the property was from the arroyo called "Where the Mexicans Weep" and it was hauled in by the Indians in the wagons. [164] Most of the building timbers, especially that used for vigas and larger structural features was brought in from the Defiance Plateau area.

Dorothy Hubbell noted that "we got our adobe right here. .I think they were doing it back of the old chapter house" while specimens of petrified wood and other minerals were collected from throughout the site and surrounding landscape and subsequently used for ornamentation and the creation of planting beds for the flower garden. [165] Locally available woods were used for firewood around the post and home. The majority of this wood was obtained from many of the Navajo who traded with the Hubbells. According to Hubbell Parker, the pinyon was used "to burn in the fireplace because it burned without crackling" and the cedar which makes sparks was used in the stoves. [166]

Cultural Traditions

The historic landscape associated with the Hubbell Trading Post reveals a mix of Hispanic, Navajo, and Anglo-American cultural traditions. Many of the buildings and structures including the trading post, barn, and Hubbell residence reflect both Hispanic building traditions that were introduced to the site by Juan Lorenzo Hubbell and his relatives, many of whom assisted in the design and construction. The use of thick double adobe walls, lattias, simple rectangular buildings, and exposed vigas are all characteristic of the Hispanic building tradition. Other features that reflect Hispanic building traditions include the lack of a mantel over the large fireplace and a corner fireplace that was formerly located in Room II West of the main residence. Brugge reveals that some of the Anglo-American influences are noted by contrasts with the Hispanic traditions. [167] For example the yard area is not enclosed as a patio, instead there is a large yard area in front of the residence and a barnyard to the rear of the house. There is no zaguan nor a portico and within the thick interior walls there are no niches. The windows and doors of the buildings reflect typical late nineteenth century Anglo-American styles.

The Hubbell family was also very knowledgeable of the numerous cultural traditions of the Navajo people and worked to accommodate them when and where possible. No family burial plots were located in close proximity to either the residence or the trading post as this would deter potential customers. Traditional hogans were constructed in the immediate vicinity of the trading post to provide overnight shelter for customers who had traveled long distances to trade at the post. Stone and other readily available building materials were not taken from the pueblo ruin sites on the property for use in the Hubbell's construction efforts because J.L. Hubbell acknowledged that the Navajo's discomfort associated with ruin sites would preclude their use of the trading post or their visitation to the site in general.

The Hubbell's allowed Navajo medicine men and community members alike to gather a variety of plant materials from the site to be used for different purposes ranging including nutritional, medicinal, and ceremonial. Some of the plants included the nuts, mulberries and other fruits, as well as pink roses, cattails, willows, and other native plants.

The family also provided a field or use area for a variety of ceremonies, traditional games and community activities such as the chicken pull and sheep dipping, etc. and accommodated numerous overnight guests during these times. Of course the congregations of people meant increased business for the trading post as well. According to Dorothy Hubbell:

We held our own rodeos. They were usually on the 4th of July. Mr. Hubbell would offer prizes for the horse races, foot races, sack races, and such. Every summer in August we would have a big chicken pull here with horse races and other events. Before one of these Roman had the arroyo dragged so that it could be used as a landing strip and gave airplane rides to all the Indians who wanted to go up. [168]

Having been raised on the reservation, Hubbell's younger son Roman adopted many of the Navajo's traditions including the use of a sweat lodge. Dorothy Hubbell noted that Friday Kinlichinee built traditional sweat lodges for Roman's use and located them west of the stone bunkhouse beyond the cornfields. No evidence of these temporary structures was located during field investigations.

Anglo-American cultural traditions did not seem to become evident within the landscape until the late teens and early 1920's. Around this time the "Eastern" aesthetic with regard to the residential landscape became more pronounced as the family added shade trees (which were largely unsuccessful) and assorted flower beds in and around the yard area. It should be noted that this was also the period that Hubbell's daughters returned to Ganado to take up residence and Dorothy Smith (later to become Dorothy Hubbell) arrived from the East to serve as the Hubbell grandchildren's schoolteacher. Dorothy made reference to the fact that following visits by friends and family from the East they would receive a variety of flowers, slips, and bulbs for gardening purposes.

As for the overall orientation and layout of the fields, irrigation canals, and placement of fruit, nut, and shade trees it has been hypothesized that this might have originated from J.L. Hubbell's associations with persons from New Mexico like his long time partner C.N. Cotton as well as his associations with the Navajo and military agents at Ft. Defiance and Ft. Wingate. There are also several early farming and irrigation related books and primers in J.L. Hubbell's private library that he most likely used to gather ideas from for his farming operation.

Historically, the Hubbell landscape has represented the cultural traditions associated with three distinct cultural groups. Many of these features or characteristics are still evident today and park management continues to be aware of and sensitive to cultural differences and preferences. For this reason, cultural traditions and the features that represent them contribute to the overall integrity of the landscape with regard to its design, materials, workmanship, and associations.

Structures

Over the years numerous buildings and structures have been part of the landscape that is now associated with the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site. Prehistorically there were likely a variety of less than permanent structures including ramadas and lean-to shelters followed by pithouses and later multi-roomed pueblo villages or settlements. The locations of several early Navajo hogans have also been identified through archeological investigations and references have been made in some of the park's oral histories providing the local folklore regarding early inhabitants of these sites. [169]

Around 1874 or 1875 trader William Leonard constructed the first trading post on the property. It is believed that the building was a simple two-room jacal structure with a stone chimney against the exterior north wall of each room. [170] By 1878 J.L. Hubbell had acquired the property and it is hypothesized that he immediately added to Leonard's original building complex by adding a multi-roomed jacal and masonry structure to the south of the first building. This new building served as the living quarters for the Hubbell family until they moved to their large adobe residence in 1902. The addition to the Leonard complex is described as having interior chimneys and one small room of stone masonry in addition to the pine post jacal walls that enclosed most of the rooms. [171] Following the family's departure from these buildings they saw a variety of uses. The original site structure to the north served as J.L. Hubbell's office, an art studio for E.A. Burbank, and overnight lodging facilities for a variety of guests. The remainder of the complex was used as quarters for various Hubbell employees, guests, and customers until its condition was determined hazardous and it the entire building complex was demolished in 1923.

In addition to the small two room jacal that developed into the first trading post complex on site it has been suggested that the original portion of the manager's residence was constructed sometime between 1874 and 1897. Several modifications and additions were subsequently made to this building until it reached its present footprint around 1931.

By 1883 Hubbell had begun construction on a new and larger masonry trading post building beginning with the office and rug room sections of the existing building. In 1889 the store and wareroom were added and the post attained its present floor plan. Construction on the masonry barn was initiated in 1893 and by 1895 the single story structure was completed. Additions and modifications in the footprint of the barn were made sometime prior to 1906 and by 1909 the second story was added to the northwest corner.

As noted earlier in this report, the year 1897 saw numerous changes with regard to Hubbell's development of the property. The corrals and sheep pens were added as was the first of the family's bread ovens. The first rooms that were later to become part of the Hubbell residence might also have been constructed at this time along with a variety of sheds, a well house, and additional fencing in the immediate vicinity of the new trading post.

Around 1900 Hubbell began construction on his large adobe residence which included a wide main hall and five flanking rooms. By 1902 construction was completed and the family was moving in to their new home. The next major phase for building activities did not occur until the period from 1906 till about 1913. In 1906 the utility building which now serves as the chicken house was built to house the family's generator and provide quarters for staff. A second bread oven was constructed and additions to the barn were added. Substantial changes were made to the family residence in 1910 as the kitchen, school room and an additional bedroom were connected to the main residence and the small courtyard was created by the joining of these two structures. A wooden vestibule was also added to the north entry of the trading post although it was removed after a few years.

In 1913 the stone bunkhouse was added and it originally included a large garage which was later demolished by the family in the mid to late 1930's. This structure served as quarters for the freight wagon and truck rivers and other trading post employees. Another building episode occurred around 1920 at which time the family constructed an addition to the trading post wareroom and built a small stone and adobe structure to the northeast of the trading post. This small building was used to house their Delco batteries. They also constructed two traditional Navajo hogans in this same general area to provide overnight lodging for customers who had traveled long distances and needed accommodation. A stone school building was also constructed during this time and was sited immediately north of the small Delco structure. By 1924 Hubbell was leasing this property to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) for use as a school.

Sometime during the early 1920's the family added a shed structure immediately south of the main residence to house coal and later wood for use in the house. Dorothy Hubbell noted that the use of coal was too messy and they quickly switched back to wood for fuel and the shed was used as a carport for her automobile until it was demolished a few years later. By 1926 the bread oven was rebuilt, this time to its present appearance. Although it should be noted that the bread ovens historically included an open shed-like structure over them and these sheds are no longer evident except through archeological investigations (figures 97 and 98).

There are discrepancies in the accounts regarding the construction date for the "hogan in the lane". The National Register nomination form and a few other accounts mention that this structure was constructed as early as 1930 however other references note that the hogan was built by Friday Kinlichinee and it was not constructed until 1950 or thereabouts. According to Friday Kinlichinee's family, the hogan was originally constructed by Richard Dentman (Friday's wife's brother) although it's original location was approximately two miles from the Hubbell property. Sometime during late 1940 or early 1941 Friday and Richard dismantled the hogan and moved it to its present location in the lane on the Hubbell property. It was then reassembled and utilized by Friday while he worked for the Hubbell family.

Construction began on the stone guest hogan in 1934 yet the building was not completed until the early 1940's. Also during the 1940's a frame house was constructed on the school house tract that was being leased to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). By the 1960's another frame house was added to this site and both buildings were determined non-historic and removed by the National Park Service in 1979.

The majority of the historic buildings and structures associated with the development and evolution of the Hubbell landscape are still existing on site and are in fair to very good condition. There are 13 historic buildings and literally hundreds of historic structures available for today's visitor to see, touch, and experience first-hand all in their original locations and reflecting the building materials selected by the Hubbell family and the many hands that helped them develop the site. All of these historic buildings and structures are highly significant and through their design, layout, materials, workmanship, and associations contribute to the integrity of this incredible landscape and help convey its special "sense of place" with regard to the Navajo trader, early settlement in the Southwest, and the Hubbell family.

|

| Figure 97. Bread oven and shed west of Hubbell home, post 1910. (HUTR 8655) |

|

| Figure 98. Bread oven and shed west of Hubbell home, post 1910. (HUTR 4446). |

Views and Vistas

Historically, the views and vistas associated with the Hubbell property were open and expansive with few, if any visual barriers. The naturally low rolling terrain and mid-story scrubby vegetation that comprise this landscape promote its open nature. Even prior to the extensive land clearing for the establishment of agricultural fields, the views and vistas would have been somewhat restricted for those entering or occupying the site of the trading post. However, the higher elevation locations would have provided some open views of the surrounding landscape.

The long straight wagons roads leading into and from the trading post provided linear views of the landscape and allowed the family to sight the freight and mail wagons coming in from several miles in many directions. The distinctiveness of the Hubbell farm and trading post landscape with its expansive green fields and combination of cottonwood and fruit trees also served to draw visitors and customers alike to the Hubbell's door. Signs and other forms of advertisement were not needed at the early trading posts as few if any of the customers read either English or Spanish and generally learned of the posts existence and its offerings by word of mouth.

While there are some modern visual intrusions, these are relatively few and many of the views and vistas enjoyed by the present day visitor provide an excellent overview of the historical layout of this significant and characteristic trading post operation and many of the views are remarkably similar to those enjoyed throughout the site's history. The visual quality and viewing range of this area contributes as one of the character-defining elements within this cultural landscape and should be protected.

Archaeological Resources

Based on oral histories, it is obvious that the Hubbell family was well aware of the numerous archeological ruins and sites found across their homestead property. The large readily visible sites with structural ruins such as Wide Reed Ruin were avoided and left virtually undisturbed out of deference to the concerns and taboos of the Navajo community. During an interview Dorothy Hubbell noted that:

Mr. Hubbell was very particular not to let anyone disturb Wide Reeds Ruin. I would feel sure that no stones were taken from there for use in the building here. He was always hoping to have it restored. He talked to me many times about it. [172]

Some of the smaller sites and artifact scatters were included within the lands that were cleared, ditched, terraced, and plowed for cultivation. Artifacts from some of these sites were collected by the family and added to personal collections or used for either site or building ornamentation. Dorothy Hubbell mentioned that "over by the west fence there is a ruin and some burials and some of the pottery is from there (pottery used in the fireplace of the guest hogan). [173]

The scatters of artifacts associated with several of these sites are still readily evident today as one traverses the old field terraces. Along the southern boundary of the big field there is a fairly large archeological site that is somewhat mounded and contains a moderate to high artifact density on the ground surface. It appears that the Hubbells began to run the head ditch through this site and at a later date diverted the excavation and brought the ditch along the south side of it rather than through it. Their reasoning for this switch has not been documented but might possibly reflect a hesitancy on the part of the workers to further disturb the archeological site.

Boundaries

During Hubbell's early years at the Ganado site the land had not been surveyed and therefore no official boundaries established. With the expansion of the Navajo Reservation boundaries in 1880 and the coming of the railroad and the land grab that followed Hubbell likely became more aware of trying to establish his claim on a 160 acre homestead.

By the early 1900s Hubbell began to establish property boundaries by clearing and fencing off his agricultural fields, yet he continued to make active use of lands clearly not included within his homestead claim. The construction of the holding pond or reservoir was officially off of his property as was the land selected for the construction of the Ganado dam and the main canal that brought water to his farm fields.

The Hubbell family's active use of property not officially held in their ownership continued throughout their occupation and management of the site. The cattle corrals located north of the Pueblo Colorado Wash were located beyond their homestead boundaries as was Hubbell Hill where seven of the Hubbell family are buried.

The concept of boundaries seems to have been beneficial to the family with regard to legal matters and claims but on a daily operational basis they were likely established through locally regulated agreements with neighboring Navajo families.

Small Scale Features

Historically, the landscape associated with the Hubbell trading post and farm was comprised of a plethora of small scale features many of which are still present today. Early on the Hubbell family maintained a simple complex that provided for housing and trading but as the operation grew and additional buildings and activities were incorporated the number of small scale features within the landscape also increased.

During the years that the original Leonard complex was occupied and added to by the Hubbell family the primary character-defining small scale features included the various types of fencing used to enclose the yard (Appendix 5) and other use areas, as well as water troughs, water buckets and barrels, and wood piles. As with most vernacular landscapes, the amount of small scale features (often confused as "clutter") that characterize the function and use areas of the landscape increases over time. This is certainly true of the Hubbell landscape as revealed through historic photographs.

With the addition of the agricultural fields came the need for an irrigation system with all of its associated features such as ditches, headgates, siphons, and flumes; fencing was then needed to protect the fields from free-ranging livestock, gates were needed for fences and stiles were needed for easy pedestrian access across the property as most early customers arrived at the trading post either on foot or horseback and later by wagon. As the years went on more site amenities were added to the landscape and included stepping stone or boardwalk paths, clotheslines, and eventually decorative features and garden ornamentation. By the mid 1920's members of the family (primarily Roman) had brought in old wagon wheels and numerous mineral specimens for delineating flower beds or just placing around the trading post and residential landscape for ornamentation.

Through the availability of detailed oral histories there is some very specific information regarding several of the site's existing small scale features. For example, "the wagon wheel (against the west side of the porch) originally came from here. When I was in Winslow I wanted one for our patio and Roman brought it to Winslow for that purpose. When we returned to Ganado it was brought back here." [174]

Hubbell's granddaughter LaCharles was living at the trading post as a small child and remembered that "the dinner bell was once over the kitchen door. I do remember when it was on the rafters coming out from the kitchen there, but I don't remember why they moved it." [175] Then Hubbell's daughter-in-law adds, "the dinner bell was on the same rack as at present when I came (1920). It was necessary to climb the ladder to ring it. The bell on the ground by the old elm tree between the trading post and the house is probably the one that was on top of the old house. I think Roman brought in the bell now on the post by the corner of the house. .I do not know just where it came from." [176]

As for other small scale features Dorothy mentioned that "the swing (on the front porch) was here when I arrived (1920)...and the log trough between the trading post and the home was originally at the pump down toward the arroyo. I had it moved to its present location to use as a planter...it used to be filled with nasturtiums." [177] She also noted that the big iron kettle by the guest hogan was used to render lard and that the sundial in the garden was given to John Hubbell by W.B. Meyers. An early photograph reveals the sundial is in approximately the same location today.

Dorothy also mentioned the iron gate in the stone wall between the trading post and the Hubbell home with Hubbell's initials "JLH" incorporated into the design and noted that this gate as well as the large iron gates in the area of the barn were made by the family's blacksmith Joe Borrego. [178]

The presence of pets and animals within a landscape might also be considered character-defining small scale features and the Hubbell landscape certainly had its share or these. Again the oral histories and historic photographs are essential to identify the variety of animal life that were an integral part of the Hubbell landscape.

Dorothy Hubbell commented:

We (the Hubbells) sold very little livestock to the Indians. At one time we got some rambouille rams to sell to the Navajos, but that is the only time I recall. We bought lambs and kept them on the place. There were some years that we couldn't sell the lambs and had to feed them until they could be sold in January. For feeding we sometimes sent them to Loveland, CO and once to Kansas City and once to the Phoenix area. During the last years we only bought what was brought in here, but Roman used to go from hogan to hogan, camping out, and start all the sheep from various places to meet here then drive them to the railroad. At first the herds were just driven to the railroad on foot. Later they used trucks...when herds were driven...had to coordinate movement from different posts. It was always a regular thing to buy lambs in the fall. We did not buy in any quantity through the rest of the year...only an occasional animal for use for meat here. I bought lambs until the last four years I was here....I was here until March 1st, 1967. [179]

She also mentioned that:

We had 66 horses and mules including those used for hauling freight, and the saddle horses. We had one burro that the children used to ride. We never maintained a herd of sheep. We bought a few cattle from the Indians. There were no oxen here while I was here.

For a couple of years only we had pigs. We didn't like them. The pigs would always get out. We had chickens. We found eggs in the hay. We also had turkeys, guinea hens, and peacocks. The peacocks would also lay eggs. The Indians would chase them for their feathers. They were lost in very cold weather. They had them in 1920, for how long before I don't know. [180]

It is interesting to note that many trading posts throughout the desert southwest maintained at least a few if not a small flock of pea fowl as they not only served as watchdogs of sorts but also are said to keep an area "free of rattlesnakes".

Dorothy continues her description of the animals associated with the Hubbell landscape:

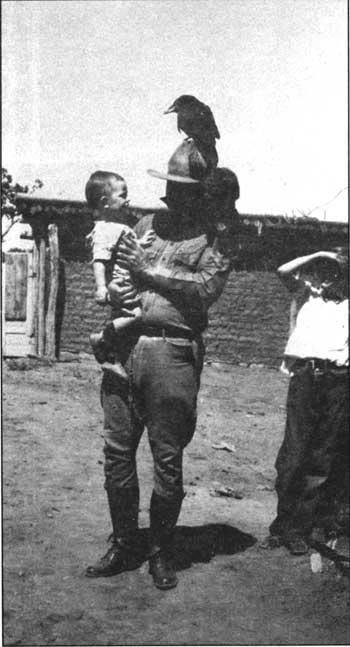

In the 20's we had two milk cows. We had chickens. .some were Rhode Island Reds, but most were no special variety. We had 15 to 18 turkeys. We had peacocks all through the 20's. One real cold winter in the 30's they froze. We had two with beautiful tails and 8 or 10 altogether with the hens. We had guinea hens, but for only a year or two. We bought and sold some goats. We had no ducks or geese. We did have a couple of eagles when John was a boy. We found them in a nest and John fed them raw meat. They were sort of dangerous. We also had a pet crow. John found the crow's nest and watched until the egg hatched and the baby grew a little and then brought it home. He called it Jimmy. [181]

The crow ate the peacock eggs. The crow really bothered Saiz. Saiz would be putting in onion sets and the crow would follow right behind him pulling them out. It also used to steal his nails while he was repairing the fences. [182]

We also one time had a little badger in a cage. Then at one time he had guinea pigs. Once he had a white rat but I made him give it away. We had two Airedales, Hobo and Charlie. Diane was a beautiful little German Shepherd pup. Then there was "Big Ox" who was just a dog...also a little terrier named Roscoe...LaCharles had a St. Bernard.

We had a pet bobcat at one time. We had to keep it in a cage all the time...we didn't keep it long. The children had little turtles from time to time...we also had canaries. We had a tank of little guppies several times. John raised them. We also had a pet monkey,"Eva". We kept a big bull snake in the wareroom to get the mice. [183]

With the exception of the assemblage of pets and other animals (figures 99 and 100), the majority of the small scale features described above continue to be found within the Hubbell landscape along with myriad other features that date from the landscape's period of historic significance such as the "bone yard", stockpiles of wood and stone, and a vast assortment of farm equipment including wagons, haybalers, manure spreaders, and plows. Peterson provides good descriptive and operational information for these various features as they were utilized by the Hubbell family. [184] The continued presence of all of these features contribute greatly to the integrity of the vernacular landscape and should be retained to fully convey the "spirit" of the working landscape.