|

COLONIAL

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestone: The First Century |

|

APPENDIX A:

Natives in the Landscape: Images and Documents of Seventeenth Century Virginia Indians

Compiled by Buck Woodard

Indigenous Material Culture Imagery

Purpose: To document and summarize select extant primary and secondary sources of American Indian imagery and material culture in relationship to the period of the first permanent English Settlement at Jamestown. Evaluation of resources to be included: 1) Annotated list of image sources containing content on Mid-Atlantic American Indians, with emphasis on the Southern Algonquians in the Chesapeake and Albemarle drainage; 2) description, location, and catalogue of select contact period material cultural items relative to the scope of study; 3) catalogue of images of seventeenth-century documents and maps relative to Native populations.

I. Annotated List of Image

Resources

The Paintings of John White

Virginia's first colony was actually located in what is today Roanoke Island, North Carolina. White was the artist and cartographer of the first Virginia colony in 1585 and later the governor of the famed 1587 "Lost Colony". He recorded much of what he saw of Albemarle Natives in the form of watercolor paintings and select field descriptions. While the images of Native life have been listed below, White's record of the flora and fauna of the Carolina Coast has been omitted. The following list of originals are owned and copyrighted by the British Museum in London.

*only select images have been visually reproduced because of the familiarity with most of the White / DeBry paintings and engravings.

1) "The manner of their attire and painting them selues when they goe to their generall hunting, or at theire solemne feasts." Reg. # LB 13. ECM 48. 1906.5 9.1 (12). Neg. # 5254. British Museum

2) "The wyfe of an herowan of Secotan." Reg. # LB 19. ECM 37. 1906.5.9.1 (18). Neg. # 5260. British Museum

3) "One of their religious men." Reg. # LB 15. ECM 42. 1906.5.9.1 (14). Neg. # 5256. British Museum

4) "One of the wyues of Wyngyno." Reg. # LB 18. ECM 47. 1906.5.9.1. (17). Neg. #5259. British Museum

5) " Chiefe Herowan." Reg. # LB 22. ECM 46. 1906.5.9.1 (21). Neg. # 5263. British Museum

6) "A Chiefe Herowan wyfe of Pomeoc and her daughter of the age of 8 or 10 years." Reg. #LB 16. ECM 33 1906.5.9.1 (13). Neg# 5257. British Museum

7) "The aged man in his winter garment." Reg. # LB 20. ECM 34.1906.5.9.1(19). Neg. #5261 British Museum

8) "The Wyfe of An Herowan of Pomeiooc" Reg. # LB 14. ECM 34. 1906.5.9.1(15) Neg. # 5255. British Museum

9) "The Flyer" Reg. #LB 17. ECM 49. 1906.5.9.1 (16). Neg. # 5258. British Museum

10) "The Manner of Their Fishing." Reg. # LB 5. ECM 43. 1906.5.9.1 Neg. # 5246. British Museum

11) "Their Sitting at Meate." Reg. # LB 5. ECM 41. 1906.5.9.1 (20). Neg # 5262. British Museum

12) "Ceremony of Sitting Round A Fire" Reg. # LB 10. ECM 40. 1906.5.9.1 (11) Neg. #5251. British Museum

13) "Religeous Dance" Reg. # LB 9. ECM 49. 1906.5.9.1 (16). Neg. # 5250. British Museum

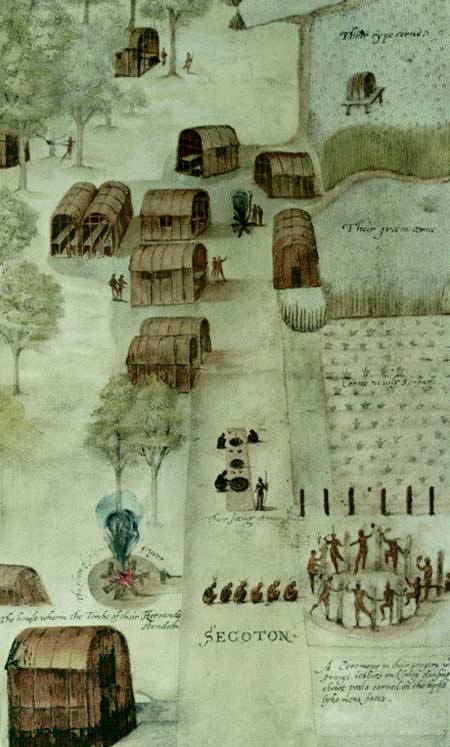

14) "Secotan" Reg. # LB 6. ECM 36. 1906.5.9.1 (7). Neg. # 5247. British style='mso-tab-count:3'> Museum

15) "The Tombe of Their Cherounes or Cheife Personages" Reg. # LB 8. ECM 38. 1906.5.9.1 (9). Neg. # 5249. British Museum

16) "The Town of Pomeiock and True Form of Thier Houses" Reg. # LB 7. ECM 32. 1906.5.9.1 (8). Neg. # 5248. British Museum

The Engravings of Theodore de Bry

Theodore de Bry was a Flemish engraver and goldsmith. He worked primarily in Frankfurt and never actually saw the American continent that he is so well remembered for depicting. For his 1591 publication, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, De Bry produced 23 engravings after John White's watercolors. His additional 1591 publication of Brevis Narritio Eorvm Qvae in Florida Americae Provicia, a narrative after paintings produced by Jaques le Moyne de Morgues of a French Huguenot colony, make these the earliest published images of Native life in what is today the Southeastern United States.

Titles and Descriptions for engravings taken from the 1893 edition of Hariot's Narrative of the First Plantation of Virginia in 1585..., Compliments of the New York Public Library.

* only select images have been visually reproduced because of the familiarity with most of the White / DeBry paintings and engravings.

1) "A WEROAN OR GREAT LORDE OF VIRGINIA." Engraving number 3 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/4 x 5 7/8 inches.

2) "ONE OF THE CHEIFF LADYES OF SECOTA." Engraving number 4 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/4 x 5 7/8 inches.

3) "ONE OF THE RELIGEOUS MEN IN THE TOWNE OF SECOTA." Engraving number 5 from De Bry, 1590. Engraved by G. Veen. 8 3/4 x 6 1/4 inches.

4) "A YOUNGE GENTILL WOEMAN DOUGHTER OF SECOTA." Engraving style='mso-tab-count: 2'> number 6 from De Bry, 1590. Engraved by G. Veen. 8 3/4 x 5 7/8 inches.

5) "A CHIEF LORD OF ROANOAC." Engraving number 7 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches.

6) "A CHIEF LADYE OF POMEIOOC" Engraving number 8 from De Bry, 1590. 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 inches.

7) "AN AGED MAN IN HIS WINTER GARMENT." Engraving number 9 from De Bry, 1590. 8 5/8 x 6 inches.

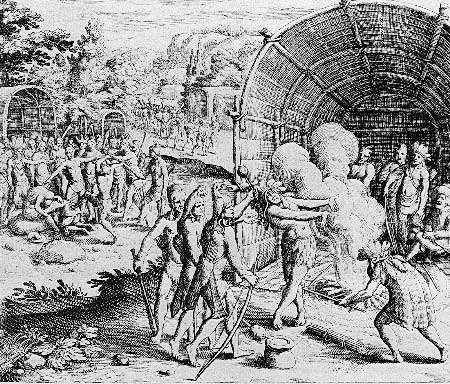

8) "THEIR MANNER OF CAREYNGE THER CHILDREN AND ATYERE OF THE CHEIFFE LADYES OF THE TOWN OF DASAMONQUEPEUC" Engraving number 10 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/8 x 5 5/8 inches.

9) "THE CONIUERER" Engraving number 11 from De Bry, 1590. Engraved by G. Veen. 8 1/2 x 6 inches.

10) "THE MANNER OF MAKINGE THEIR BOATES" Engraving number 12 from De Bry, 1590. 8 1/2 x 5 7/8 inches.

11) "THEIR MANNER OF FISHYNGE IN VIRGINIA" Engraving number 13 from De Bry, 1590. 12 1/2 x 10 3/8 inches.

12) "THE BROVVYLINGE OF THEIR FIFHE OUER THE FLAME" Engraving style='mso-tab-count:1'> number 14 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/8 x 5 1/4 inches.

13) "THEIR FEETHEYNGE OF THEIR MEATE IN EARTHERN POTTES." style='mso-tab-count: 2'> Engraving number 15 from De Bry, 1590. Engraved by G. Veen. 81/4 x 5 5/8 inches.

14) "THEIR FITTING AT MEATE." Engraving number 16 from De Bry, 1590. 8 1/2 x 6 inches.

15)"THEIR MANNER OF PRAINGE VVITH RATTELS ABOWT THE FYER" Engraving number 17 from De Bry, 1590. 10 1/8 x 7 1/4 inches.

16) "THEIR DANFES THEY VFE ATT THEIR HYGHE FEAFTES" Engraving number 18 from De Bry, 1590. 12 5/8 x 10 1/2 inches.

17) "THE TOWNE OF POMEIOOC." Engraving number 19 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/4 x 11 1/2 inches.

18) "THE TOVVNE OF SECOTA." Engraving number 20 from De Bry, 1590. 9 x 12 1/4 inches.

19) "THE TOMBE OF THEIR WEROVVANS OR CHIEF LORDES." Engraving number 22 from De Bry, 1590. 9 x 12 3/4 inches.

20) "THER IDOL KIVVAFA." Engraving number 21 from De Bry, 1590. 8 1/2 x 6 1/8 inches.

21) "THE MARCKES OF FUNDRYE OF THE CHEIF MENE OF VIRGINIA." style='mso-tab-count: 2'> Engraving number 23 from De Bry, 1590. 8 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches.

* Images based on Theodore De Bry's engravings of John White's watercolors dominate the majority of the Virginia Indian visual representation for the 17th and 18th Examples of these reproductions have been included below.

Robert Beverly used Simon Gribelin as his engraver for the 1705 publication of "The History and Present State of Virginia". While Gribelin copied directly from DeBry, he added various elements at Beverly's request. Beverly felt that the new engravings adequately illustrated the Virginia Natives as well as added to the understanding of Virginia's Indians.

Simon Gribelin

1) "A Woman and a Boy Running after Her," Engraving by Simon Gribelin. From Robert Beverly, History and Present State of Virginia, London 1705.

2) "A Priest and a Conjurer in their proper Habits," Engraving by Simon Gribelin. From Robert Beverly, History and Present State of Virginia, London 1705.

Georg Keller

Georg Keller worked for both DeBry and for their competitor - Hulsius, as an engraver and illustrator. His work appears in several publications however, the material is colored by his experiences in Asia and Africa.

Examples from Hulsius (Abelius):

1) "Pocahontas meets her brothers" from a translation by Abelius of Ralph Hamor's "Present State of Virginia" as "Thirteenth Navigation", Hannua, 1617.

2) "Making a treaty with the Chickahominy Indians." from a translation by Abelius of Ralph Hamor's "Present State of Virginia" as "Thirteenth Navigation", Hannua, 1617.

Examples of the same material produced later by the De Bry engravers:

1) "Captain Smith Saved by Pocahontas" Discovering the New World, based on the works of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Alexander, ed. 1976

2) "The abduction of Pocahontas" Discovering the New World, based on the works style='mso-tab-count:1'> of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Alexander, ed. 1976

3) "Pocahontas is visited by her brothers" Discovering the New World, based on the works of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Alexander, ed. 1976

4) "The Chickahominy become 'New Englishmen'" Discovering the New World, based on the works of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Alexander, ed. 1976

5) "Ralph Hamor tells how he was sent for Powhatan's other daughter" Discovering the New World, based on the works of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Aleander, ed. 1976

6) "The massacre of the settlers" Discovering the New World, based on the works of Theodore De Bry, Micheal Aleander, ed. 1976

Robert Vaughan

Robert Vaughan worked as an illustrator during the middle of the seventeenth-century. His work is based on De Bry and White, however his earliest work was for John Smith. He corrects some of De Bry's mistakes in coordination with Smith's requests.

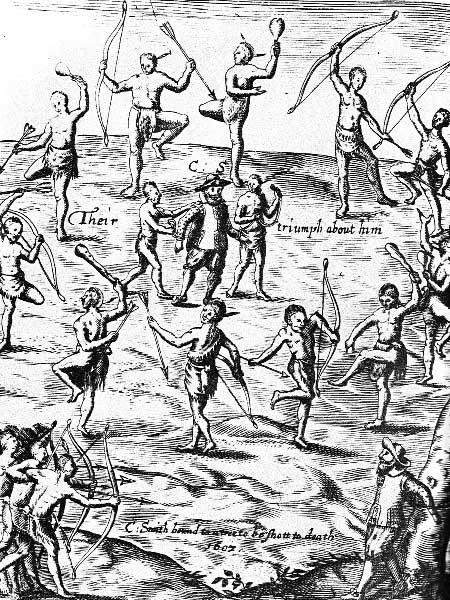

1) "Their triumph about him", General Historie, John Smith, London, 1624

2) "A Coniurer", General Historie, John Smith, London, 1624

3) "C: Smith Taketh the King of Pamaunkee prisoner 1608." General Historie, John Smith, London, 1624

4) "C: Smith takes the King of Paspehegh prisoner." General Historie, John Smith, London, 1624

Simon Van De Pass

MATOAKA (POCAHONTAS). Line engraving 6 3/4 x 4 1/2 inches. London. 1616 British Museum. Reg. No. 1863.5.9.625.

Artist Unknown (British)

Lottery Broadside featuring Eiakintomino and Matahan, 1615.

Artist Unknown (British? School)

POCAHONTAS. The "Booton" portrait. Oil on Canvas. 30 x 25 inches. England. 1616. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Mellon Collection, NPG 21.

This portrait was owned by the Rev. Whitwell Elwin, Booton Rectory, Norfolk, England. The family was supposedly related to the Rolfe family, and they maintain that this painting was created by an Italian Artist.

Wencelaus Hollar

INDIAN OF VIRGINIA, MALE. ("Vnus Americanus ex Virginia, Aetat: 23 (age 23) W. Hollar ad viuam delia: et fecit., (made from life) 1645")

Francis Louis Michel

"DREY AMERICANS." Three Americans. Powhatan? Southern Algonquian. Original pen drawing washed with watercolor, Found in "Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel from Berne, Switzerland, to Virginia, October 2, 1701 - December 1, 1702.

The original manuscript is lost. This document is a contemporary copy made by Michel's brother, John Louis Michel. Size 16 x 13.5 cm, Call Number: Burgerbibliothek Bern, Mss. hist. helv. X.152, fol. 64a.

Michel's image depicts several Algonquians wearing a combination of animal skins and plant fibers. Their hats are described in Beverly's account of the "The History and Present State of Virginia" as being made of bark, round and open on the top and wrought with shell peak to make designs. The baskets are mentioned as being carried on the arms as shown in Michel's account, along with comments on singing, dress, and customs.

William Byrd II

Detail of the lower third of the print of the Williamsburg public buildings showing American Indians, floras, and fauna. Early 18th century publication, apprentice engraver.

Copied from "William Byrd II and His Lost History: Engravings of the Americas", Pritchard and Sites, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

North Carolina Museum of History

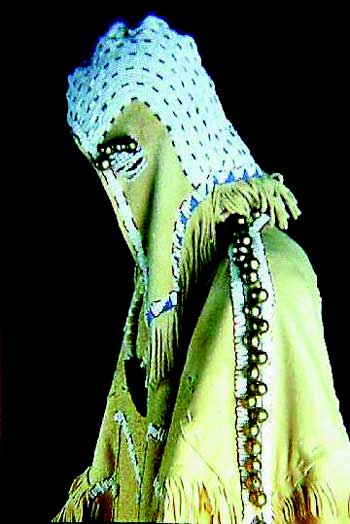

The collection of images from the North Carolina Museum of History are of a reconstructed regalia and life model of a Carolina Siouan woman believed to be from the Saura tribe. The seventeenth-century site was believed to have been heavily traded with by the coastal English settlers during the contact period, evidenced by the high count of trade materials present. Within the image series, red, white, and blue glass trade beads, brass and copper pendants, brass bells and chevron beads can be seen adorning the buckskin clothing. Shell beads are also present, indicating the transitional materials of the period.

II. Description, Location and Catalogue of

Select Contact Period Material Cultural Items

1) Powhatan's Mantle

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England

This item is constructed of four deerskins measuring a total of 7ft. 8 1/2 in. x 5ft. 3in. The embroidery is constructed of sewn Marginella shells in several configurations. There are 34 disc shapes surrounding two animals and one central human figure. The animals appear to be that of a cougar and a deer. The top of the piece has a V-shaped opening, but it is supposed by scholars that this item was not worn, but rather hung in a temple or palatial interior. Documented by at least 1634.

2) Powhatan Bows

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England

Two early bows constructed of probably mulberry. Both bows have rounded tapering limbs from the center of the handle area, although no clear designation for the handle is indicated. In a sense, the handle area is a "working" portion of the limb. One bow measures 68 1/2 in. long, at a maximum of 1 11/16 in. at the handle thickness. At that point, a cluster of five dots is present on the back of the bow. The belly is less severe in cross section, giving a rounded appearance to the bow from the archer's point of view. The second bow measures 67 in. lengthwise, and appears to be more elliptical in the center cross section. Both bows are notched with a corner cut peg at the uppers; while one bow mimics that construction for the bottom; the other has a simple side notch from the tapered end. Collected in 1665 in the Virginia Colony.

3) Powhatan Arrows

American Museum of Natural History, New

York, New York

Two arrows of an unknown date from the Powhatan. One arrow is a "blunt" from a hardwood shoot, fletched with two turkey feathers. Shallow grooves are cut in the shaft, in which the feathers have been glued and sinew wrapped. The notch has been cut parallel to the fletching. The other arrow is from split hickory. In this case, there is a broad woodenhead left on the arrow as the shaft was reduced. The fletching is glued in grooves, with the nock being cut parallel to the feathers. The tip of the arrow shaft is dyed green beneath the head. The both arrows measure 28 1/2 in. While there is no date associated with these arrow's construction, the technology is indicative of long standing archery traditions in the Mid Atlantic, especially where cane is not present.

4) Powhatan Quiver

American Museum of Natural History, New

York, New York

Deer hide quiver of an unknown date. Hair side out, tail tide to bottom, buckskin strap with overhand knot. Total strap length is 26 in. The quiver is 18 1/2 in. long with a 8" circumference. Probably collected in the late 19th century / early 20th century, this quiver is similar to ones depicted in early engravings of Powhatan warriors.

5) The Virginia Purse

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England

The bag was constructed by folding a long piece of deerskin and sewing the mid section together. After which, the ends were cut into strips. An additional piece of leather was inserted into the long tube to form a bottom. Shells beads were sewn between the strips, forming an embroidered weft and the created flaps were triangle shaped at the ends. This bag was worn over a belt, as early engravings indicate was the custom. This item is 2 ft. 6 1/2 in. by 4 1/3 in. The bag was collected during the mid seventeenth-century from the Virginia Colony.

6) Removed

7) Bone Hair pins

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period

Series of bone hairpins from a variety of Late Woodland / Contact village sites. All have been carved and altered in preparation for use in personal adornment. One from 44VB7 has a series of joining diamond patterns; another piece from the piedmont of Virginia has been heavily carved and polished to a sheen.

8) Bone Adornments

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44MY3 (Trigg

Site)

A collection of bone adornment items from a seventeenth-century contact period site near Radford Virginia. Articles include polished bird bone and carved / polished bone beads, squirrel jaw pendant, raptor beak pendants, scapula pendants, drilled mammal canines, and carved tabs.

9) Bone / Antler Tools

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44MY3

(Trigg Site)

A collection of bone and antler tools from a seventeenth-century contact period site near Radford Virginia. Shown are a deer cannon bone "beamer" for fleshing hides, a turtle shell cup, bone fish hooks, awls, and beads, a bone set quartz blade, antler projectile points, and a large antler tool (hoe, adze, or scraper).

10) Copper Pendants

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44VB7

(Great Neck Site)

Native copper was a prized commodity of the Tidewater region during the Late Woodland period. These examples of copper pendants come from a coastal village where controlled trade was important to the exchange of resources denoting cultural status.

11) Copper Adornments

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44MY3

(Trigg Site)

A sample of the type of copper adornments excavated at the Trigg site are indicative of Native produced copper found throughout the Virginias during the Late Woodland. Large and small tube beads, tab pendants, trinkets, and geometric pendants or gorgets dominate the copper artifacts from this period.

12) Shell Bead Types

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period

Different types of shell beads were produced throughout the Chesapeake region prior, during, and after the settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. Grouped by types, the beads are known variously as A) Moons, B) Peak, C) Roanoke (also called Wampum, stubbier ones were also called Runtees), D) Hairpipe Tube.

13) Shell Bead (Peak) Necklace

Virginia Department of

Historic Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact

Period

Strung shell beads were very common until colonial times in Virginia. Strands of peak were used mostly as adornment, but later as monetary elements during the Colonial period. Values of commodities were loosely established and could be traded based on lengths of peak or roanoke.

14) Shell Bead Necklace

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period

An example of peak, runtee, and hair pipe beads strung on a necklace thought to have belonged to a shaman. Beads were laboriously produced and traded to compliment personal adornment throughout the Virginias at the time of contact.

15) Shell Face

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44ST1

A rare example of a "maskette" found within the Patowomeke territory, in Stafford County, Virginia. Several other examples have been found, made from the exterior of whelk or conch shells. These masks are smaller than life-size, and are of a ceremonial nature. They usually are highly polished and carved to imitate faces with eyes, mouths, ears, etc. Other examples are found throughout the Southeast with similar markings, such as the "weeping eye" motif as found with this piece.

16) Shell Beads

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period

This mass of shell beads found in the Piedmont of Virginia is an example of the predominant shell bead type for the region. Slightly thicker than peak, these beads were strung together to create a larger necklace. Similar constructions could be made using these beads for embroidery.

17) Shell Pendants

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period

A series of shell pendants common during the Late Woodland. Often referred to as "moons" by later Colonial traders, the shapes vary from circular to elongated triangles.

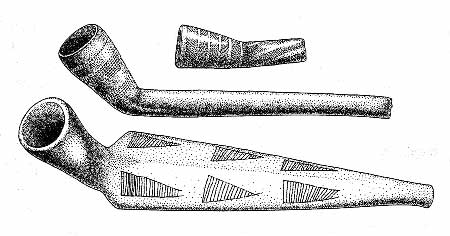

18) Patowomack Pipes

Illustration from Smithsonian

Institute

Late Woodland / Contact Period

A sample of the type of smoking utensils found during the earliest contact and post contact periods in Virginia. The upper image is of "tube" pipe of ceramic material, the middle of another clay "bowl" pipe that early Europeans emulate to make the caolin pipes, and the third of a steatite (stone) pipe. All examples found within the Patowomack territory in coastal Virginia.

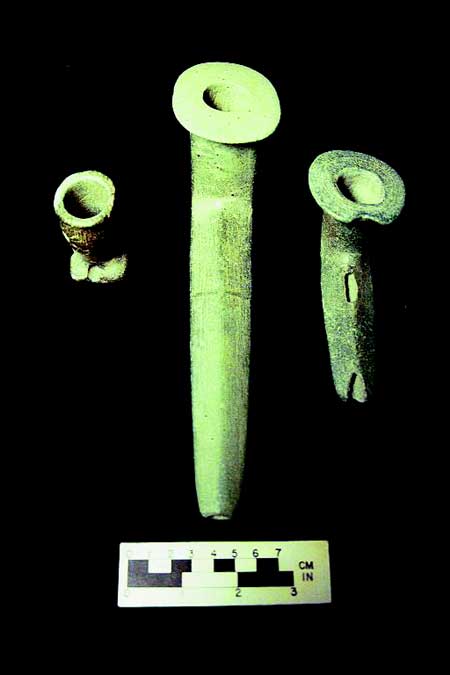

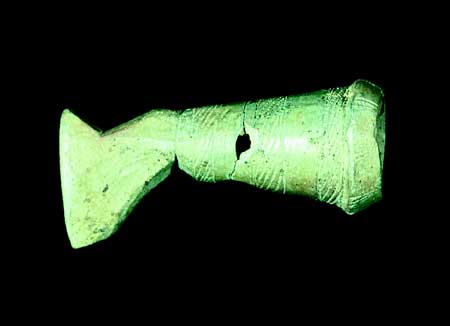

19) Nottoway Pipes

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44SN22 (Hand

Site)

Examples of finely crafted steatite pipes. The one to the left is a platform pipe with several holes for the addition of a reed stem; the other two the stems are of stone and have flared bowl heads. All three are from a seventeenth-century contact period Nottoway context.

20) Stone Gorgets

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44SN22 (Hand

Site)

A series of stone gorgets or pendants, drilled for suspension. All examples have been damaged, however their roughly rectangular shape can be discerned. These examples come from a seventeenth-century contact period Nottoway context.

21) Stone Pipe Tomahawk

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44JC33

A rare example of a European trade item reproduced in Native material. This pipe is constructed to mimic the metal trade pipe tomahawks exchanged with Native populations beginning in the seventeenth-century. Unearthed in James City Co., Virginia, this item has been carved from steatite and was found in a European context.

22) Ceramic Late Woodland / Contact Period Vessels

Virginia

Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland /

Contact Period

A collection of reconstructed vessels and large fragments of ceramic wares. Shell and sand tempered clay bodies are predominant with examples of simple stamp, fabric, and cord paddle marks. Referred to as Roanoke, Townsend, and Gaston Wares.

Typical of ceramics found at Indian settlements during the time of first European settlement.

Gaston Ware Vessel

Roanoke Ware Vessel

Roanoke Simple Stamped VB7

Townsend WareSN22

Townsend VB5

Townsend Vessel

Townsend Ware

23) Contact / Historic Period Vessels

Virginia Department of

Historic Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact

Period

A sample of reconstructed and fragmentary ceramic wares referred to as Colono-Ware. These examples come from King William Co., produced by American Indians during the later period of English Colonial occupation. The wares were documented as being sold at the market in Williamsburg during the late seventeenth-century.

Colono Jar 44KW29

Colono Plate 44KW29

25) Glass Trade Beads

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

Late Woodland / Contact Period, 44MY3

(Trigg Site)

A collection of European glass beads uncovered at a Late Woodland to Contact Period site near Radford Virginia. These seventeenth-century examples of trade into the interior of Virginia document the variety of ways in which contact with Native communities spread through the region. While person-to-person contact may not have occurred, trade commodities from other Native groups had spread from Virginia's English settlers to the interior by the mid to late seventeenth-century.

26) Colonial Badges

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia (44CE3)

Association for the

Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, Richmond, Virginia

seventeenth-century

Badges presented to Indian leaders during the time of the 1677 treaty of Middle Plantation. Badges were issued as tokens of alliance to leaders who were "cooperative" or deemed "friendly" and were to be worn when delegations entered into English controlled areas.

27) Copper Pot and Spoon

Virginia Department of Historic

Resources, Richmond, Virginia

(44GV1) seventeenth-century

Trade goods of metal found their way into Native communities almost immediately after contact. This example of a copper pot and spoon were excavated in Greenville Co., Virginia from a Late Woodland through Historic Period Indian site context.

28) Pocahontas's Earrings

Association for the Preservation of

Virginia Antiquities, Richmond, Virginia

seventeenth-century (?)

Fresh water mussel shell earrings set in precious metal bezels. The pair of earrings has been reported to have belonged to Pocahontas, according to the APVA.

Further researches into the origination of the materials and provenience have not been firmly established.

29) House Pattern

Virginia Department of Historic Resources,

Richmond, Virginia

(44VB7) Late Woodland

The image is of a probable chief's home in the present city of Virginia Beach. The structure was large and had a several entrances. Rare for the coastal plain, two storage pits can be seen on the interior.

30) House Patterns (Close up and Expanded)

Virginia

Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, Virginia

(44PG303) Late

Woodland / Contact Period

This collection of house patterns comes from an area known as Jordan's Point in Prince George Co. Virginia on the James River. It is supposed that the remains are from the seventeenth-century village of Weanock.

31) Nathaniel Bacon's Home

Foundations of Nathaniel Bacon the

Rebel's House (Curles Neck, Va.)

From "Colonial Virginia's Cooking

Dynasty" by Kathy Harbury

In the foreground are the foundations of Nathaniel Bacon's home with its square tile brick floor and well at the corner. The white foundations in the rear are the first home and then kitchen of Richard and Jane (Bolling) Randolph.

III. Image Catalogue of

seventeenth-century Maps and Documents

1) John White and Thomas Harriot, "La Virginea Pars." c.1585. Prints and Drawings Dept., ©The British Museum, London.

From the 1585 English expedition to the North Carolina coast of North America. The map illustrates major bodies of water from the region, Including the Albemarle and Pamilco Sound as well as the Chesapeake Bay (unnamed). The mouths of the York and James Rivers are also depicted in the northern section of the map. Careful attention was paid to the names and locations of local American Indian settlements.

2) Theodore DeBry, 1590, plate 1. Volume I of Theodorous de Bry,

Collectiones Pergrinationun in Indiam Occidentalem. Frankfort: T. De

Bry, 1590-1634. LVA-Map (Vorhees Collection).

A revised map of John White's original. In this version, the Chesapeake Bay appears named for the first time and the orientation has changed to the west at the top. Another map was created as a close-up of the Roanoke area specifically.

3) Robert Tindall, "The draught by Robert Tindall of Virginia

Anno: 1608." The British Museum, London.

The earliest survey map by a Jamestown colonist, Tindall's draught is an important reference to the early locations of Indian villages. It includes content based on the 1607 and 1608 expeditions of Christpher Newport.

4) John Smith, Virginia Discovered and Described by Captain John

Smith. Graven by William Hole. 1606. 8th state, c.1624. LVA-Map

(Voorhees Collection)

Smith's map is the first published map of the Chesapeake region. Oriented with the west at the top, the map has excellent detail and accuracy of Indian villages and imagery. The Smith map is the most significant visual document from the period.

*Listed below are two of a dozen or so renditions based almost entirely on Smith's map. These releases include Smith's format but often change images, add longitude lines, change, add, or delete place names, and alter the geographic image. The altered reproductions of Smith's original stay in print for most of the 17th and 18th centuries.

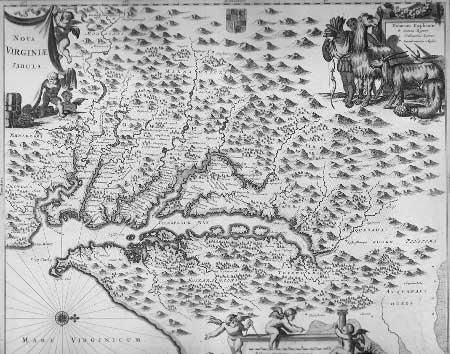

1) Arnold Montanus and John Ogilby, Nova Virginiae Tabula.

Amsterdam, 1671; style='mso-tab-count:2'> also America: Being Latest,

and Most Accurate Description of the New World. style='mso-tab-count:2'>

London, 1671. LVA-Map.

Derived from Smith, this map replaces accuracy with stereotypes developing at the time. Powhatan and the Susquehanna have been removed and replaced with cherubs and two African Natives admiring a llama, a unicorn, and a goat. However, the map's contents remain accurate.

2) Ralph Hall, Virginia, 1636. Inserted in Gerardus Mercator,

Historia Mundi: or style='mso-tab-count:2'> Mercator's Atlas. London:

Printed by T. Cotes for Michael Sparke and Samuel

style='mso-tab-count:2'> Cartwright, 1635. LVA-RBR.

Hall's map is a poor copy of Smith's earlier work. Accuracy was not the intent; most of the geography is only reminiscent of reality, as are some of the creatures (wild boar and leopards). New renditions of DeBry's engraving have been included in the bizarre landscape.

5) Don Pedro de Zuniga, Map of Virginia, before September 15,

1608. Archivo General de Simancas, Valladolid, Spain.

The famous Zuniga map offers a hand drawn version of the Jon Smith map, and the information contained there in. It also includes content on the travels to the south and west in search of Lost Colonists of Roanoke.

6) Don Alonso de Velasco, Map of the East Coast of North America,

1611. Archivo de Simancas, Valladolid, Spain.

A very detailed map collected by the Spanish Ambassador to England. The map illustrates the English understanding of the coast of N.A. from Newfoundland to the Outer Banks. Some Indian and English names appear as a list and then correlate to numbers on the drawings of rivers systems.

7) Augustine Herrman, Virginia and Maryland As it is Planted and

Inhabited this present Year 1670. Published in London, 1673.

LC-G&M

Four sheet survey of the Chesapeake Bay area, the best rendition since John Smith's original map published 50 yrs. earlier. The illustrations are detailed and outline the expanding European settlements and declining Native communities.

8) Francis Lamb, A Map of Virginia and Maryland, c. 1676.

Published by Basset and Chiswell, 1676. LC-G&M

Lamb's map is a combination of Smith's earlier work and the Herrman map. Less detail is present; however some settlements of English and Native are displayed for the period.

9) John Lederer, A Map of the Whole Territory Traversed by John

Lederer in his Three Marches. London, 1672. LVA-RBR.

Lederer's map was the first to illustrate the far interior of Virginia and Carolina. He includes several "mistakes" in his work, such as the "South Seas" and "Desserts" that are not present in reality. He includes a variety of Indian villages, of mostly Siouan extraction, with the exception of the Iroquois and Algonquians mentioned from the earliest part of his expedition.

10) "Mr. Robert Beverlys Account of Lamhatty." c.1708. Virginia

Historical Society, Richmond.

This map is an example of Indian knowledge of diverse groups and territories. Lamhatty was a Towasa, captured by Muskogees and sold into slavery to consorting Shawnees. He breaks free and makes his way to the edge of English settlement on the Mattaponi, where his story was recorded by John Walker. The map appears on the reverse of the letter to Robert Beverly, and is supposedly in Lamhatty's own hand.

11) Franz Ludwig Michel [Map of the Shenandoah Valley and Upper

Potomac River, 1707], Public Record Office, London.

The first recorded exploration of the lower Shenandoah Valley, undertaken in 1706. Michel was in search of land suitable for a Swiss colony in the region. Several of the rivers and mountainous areas are named using the local Indian dialect.

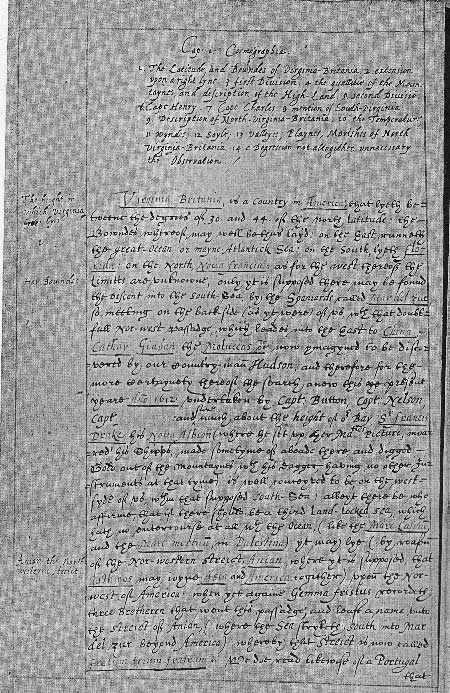

12) William Strachey, Excerpt from the "Strachey Vocabulary", the

Princeton Manuscript.

The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania

(1612)

This page from the Princeton manuscript are thought to at least have the heading and marginal notes in Strachey's hand. The entire collection is available for reproduction; two copies are extant, one at the British Museum, the other in the Bodleain Library.

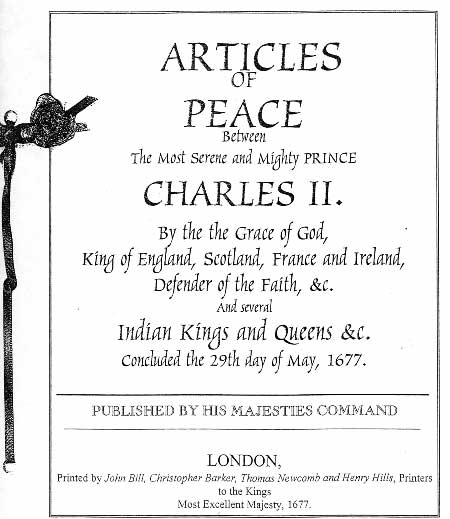

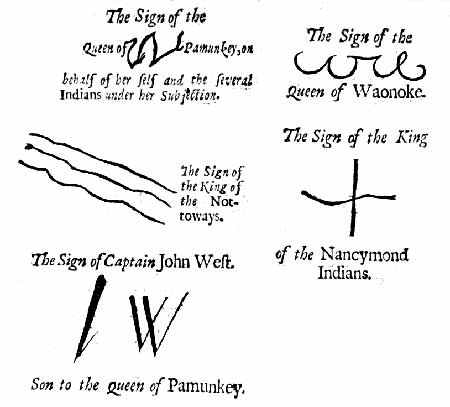

13) Treaty of Middle Plantation (Cover and Signature Page)

Printed by John Bill, Christopher Barker, Thomas Newcomb, and Henry Hills, Printers to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty, London, 1677.

The Treaty of Middle Plantation granted peace at the end of Bacon's Rebellion. Two series of signatures took place between Indians of Virginia and the British Crown. The treaties established new formal relationships and laws to govern the interaction between the colony and the Native population.

14) The Susquehana Fort

"A True Narrative of the Rise, Progress, and Cessation of the Late Rebellion in Virginia Most Humbly and Impartially Reported By His Majesties Commissioners Appointed to Enquire into the Affairs of the Said Colony." p.370 / 188 (stamped), Library of Virginia, Reel 32. Virginia Colonial Records Project.

A description and illustration of the fort at Susquehanna. An account of a July 1675 conflict is described in the article next to the map, mentioning Susquehanock and Doeg Indians in the Potomack River district.

Recommendations:

The image collection provided is a sample of the materials available for use by the National Park Service. The seventeenth-century documents are limited in number, and their use in museum work and educational publications has been extensive. Further material may be revealed in the libraries and record houses of Europe and the Caribbean. Resources in Madrid, Rome (the Vatican), Bermuda, and Barbados may await the studious researcher. Additional seventeenth-century documents are available for scanning from courthouses that are complete in their record collection, like those of the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Further studies of seventeenth-century documents pertaining to Virginia's Indians may reveal margin notes, tribal character signatures, and descriptions left out by earlier archivists. The use of seventeenth-century handwriting in museum display may be a new way to present the American Indian of Virginia. Panels dedicated to documents exclusive to Indians could offer an insight into chronology, fluctuating terms of treaties, land loss, conflict, and cultural activities. Maps that illustrate the changing face of Virginia's landscape could be used to focus on a particular area through time; detailing the changing Native names, village sites, and political control. Additional photographs of archeological study collections from across the state may provide further imagery for NPS consideration. Archeological images could be used not only in informational publications, but as design elements in larger formats for exhibitions. A display of seventeenth-century house patterns and interpreted recreations of exact local housing could be used in a dramatic way for exhibit design or just for information's sake. As an example of future image research consideration, an extensive catalogue of seventeenth-century ceramic vessel incised rim design patterns has never been done for this region. Further investigation of design elements in existing Late Woodland / Contact period archeological collections may reveal a wealth of indigenous patterned designs available for use in exhibit borders, banners, and publications or even as an exhibit focus. As a final consideration, new images could be commissioned for development. Contemporary illustrations of the Virginia Indians of the seventeenth-century are far and few between. Completed ethnographic and archeological research could provide the suitable inspiration for new imagery to be created, based on the primary materials present in this image collection.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jame/moretti-langholtz/appendixa.htm

Last Updated: 22-Nov-2006