|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Seven:

VISITOR SERVICES

From 1975 to 1995, the monument received between 90,000 and 140,000 visitors each year. [1] These numbers made it perhaps the single most significant attraction in Grant and Wheeler counties, but visitors generally did not spend more than two hours at any one of the park's three units. [2] Over three-quarters of them utilized US 26 to reach the monument, and made several points in the Sheep Rock and Painted Hills units their most popular stops. Relatively few people saw other localities once they visited the Cant Ranch complex and Sheep Rock Overlook in the former unit, or the Painted Hills Overlook and picnic area in the latter. [3] The most frequently cited reasons for coming to the monument involved viewing scenery, followed by a chance to see fossils. [4]

With much of the visitation pattern somewhat evident by 1976, the NPS strove to construct wayside exhibits, build trails, and develop basic facilities in all three units. Personal interpretive services centered on the Cant Ranch, but Ladd and other NPS employees soon noticed that its setting proved distracting and often detrimental to telling the monument's paleontological story. [5] Regional office personnel eventually responded with a preliminary site plan in an attempt to separate the ranching and fossil themes, but NPS director William Penn Mott raised several objections to it in early 1988. Nevertheless, this planning effort continued and gave rise to hopes that a main visitor center devoted exclusively to the monument's paleontological story might be constructed adjacent to the Cant Ranch complex. Congress, however, did not provide construction money once planning and design had been completed in 1993, so the NPS put the project on hold until such funding is available. [6]

Park development

At the close of his superintendent's annual report for 1980, Ladd stated that the monument "has the potential of becoming one of the most significant parks in the system to both the visitor and the scientific community if properly developed." [7] By this time he had an approved general management plan which provided a framework and gave some specifics for development, which the NPS confined to relatively small-scale projects over the next 15 years. Wayside exhibits and interpretive trails aided visitor understanding of the monument's fossil and scenic resources. Other projects resulted in improved vehicular access near trailheads, but a few had the sole purpose of enhancing recreational opportunities near the John Day River or simply supporting NPS operations.

Installation of permanent interpretive wayside exhibits took place in 1978-79 in accordance with a subsidiary plan approved prior to the GMP. [8] Executed to a park-specific design standard, the bases consisted of concrete aggregate with modulite dye transfer panels mounted on top. [9] Although Ladd expressed satisfaction with them at the time, an interpretive planning document drafted by the NPS in 1991 pointed to the need for extensive revision of text in existing wayside exhibits. [10] It also recommended locations for more of them, especially in the Sheep Rock Unit. As a result, the NPS constructed one wayside exhibit adjacent to State Highway 19 just north of Picture Gorge in 1994. It consisted of a standard fiberglass embedded panel mounted to an aluminum base, and represented a conspicuous break with the park-specific design precedent set 15 years earlier. [11]

Construction of interpretive trails within the Sheep Rock Unit began with work to improve a footpath into Blue Basin in 1978. [12] By 1985 what the NPS called the "Island in Time Trail" included a number of bridges so that hikers could avoid the fossiliferous streambed. [13] It also contained several trailside exhibits and three displays consisting of fossil replicas protected by plastic bubbles. [14] NPS crews started building Blue Basin's other trail in 1979. [15] Originally envisioned as a loop, it could not circumvent the area as planned without crossing private land. The trail remained a mile in length until the NPS secured permission from adjacent property owners. [16] When completed in 1988, the "Blue Basin Overlook Trail" totaled three miles in length, but lacked the number of interpretive devices its complement possessed. [17] The only other formal trail building in the Sheep Rock Unit took place at Foree. [18] Much like the situation at Blue Basin, the NPS wanted to restrict visitor use to two well-defined and maintained trails. This stemmed from perceived safety problems as well as potential damage to fossils from indiscriminate foot traffic. [19] Park employees responded by constructing the comparatively short "Flood of Fire" and "Foree Loop" trails in 1986. [20]

|

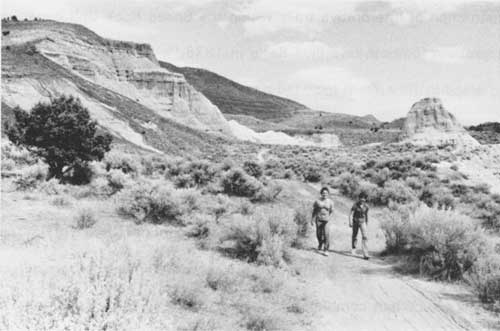

| Visitors on a hiking trail at Foree, August 1986. (NPS photo) |

Similar thinking about restricting hiker use to well-defined trails prevailed in the Painted Hills Unit, beginning at the overlook. In seeking to relocate the viewing area, the NPS wanted to obliterate one-quarter mile of old road. This resulted in a trail from a new parking area beginning in 1978. [21] Park technician Dale Schmidt built a new, but equally short, path around Painted Cove the following year. [22] The NPS subsequently developed a self-guiding nature trail and added 200 feet of boardwalk there in 1989. [23] A desire to provide more hiking opportunities in the Painted Hills Unit drove construction of a three-quarter mile long trail to the top of Carroll Rim in 1981. [24] In being somewhat analogous to the Blue Basin Overlook Trail, this project furnished visitors a spectacular view of Painted Hills and nearby Sutton Mountain. Park crews built a shorter loop trail in 1988 at Leaf Fossil Hill to allow for self-guided interpretation of the Bridge Creek Flora. [25] They added an exhibit to the trail over the following year as well as 200 yards of two-rail wood fence to better manage visitor use. [26] The NPS also approved construction of another interpretive loop in 1988, through which it hoped to highlight modern plants of the Painted Hills, but this project has yet to be undertaken. [27]

|

| Painted Hills Overlook, before conversion to hiking trail, September 1976. (NPS photo by Francis Kocis) |

All three trails in the Clarno Unit appeared in 1980. [28] Interconnected to allow visitors access from either the picnic area at Indian Canyon or via a small pullout on State Highway 218, each extended for roughly one-quarter mile. Park employees found the loop trail particularly suited to self-guided interpretation because it allowed visitors with opportunities to see actual fossils in situ. [29] This "Trail of the Fossils," however, represented a much smaller project than the original proposal to build a four mile loop through the unit to include the nut beds and mammal quarry which depended upon acquisition of the Maurer tract. [30]

A few relatively small-scale projects resulted in improved vehicular access to several localities. The largest project tied Blue Basin and Foree together, so that a single contract let in 1992 funded the paving of entrance roads and parking areas. [31] Road surfaces at Painted Hills remained unpaved, but the NPS improved parking areas associated with trailheads at Painted Cove and Leaf Fossil Hill in 1987. [32] Relocation of the Painted Hills picnic area took place in 1983 to improve circulation and allowed the development of handicapped facilities. [33] This site subsequently received an information station once park crews relocated a kiosk. [34]

Some developments could be categorized as purely to provide recreational access or solely to support NPS operations. A prominent example of the former took place in the Sheep Rock Unit with improvement of three parking areas in 1988. Each represented access to the John Day River from State Highway 19, so the NPS provided a gravel surface and delineated them with wood rail fence. [35] Establishment of seasonal quarters at Painted Hills in 1980 constituted an important example of the latter. [36] Once the NPS upgraded the facility seven years later, it provided housing for a permanent ranger on a 12 month basis. [37]

Interpretation and site planning at

the Cant Ranch

Despite having to face a number of inherent difficulties, the monument's educational program merited recognition from authors of a guide to vertebrate fossil localities in 1989 for its outstanding interpretation of paleontological resources. [38] This represented an impressive achievement, especially since the number of permanent and seasonal interpreters at any one time never exceeded four. They also had the challenge of presenting the monument's story in a park lacking focal points through which the breadth of that story could be told. Part of the problem lay in the Clarno Formation (which sets the stage for interpreting the park story, that of evolutionary change throughout the Tertiary Period) being located considerable distance from where other formations such as the John Day, Mascall, and Rattlesnake, are so plainly evident. [39]

Even with one employee stationed at Painted Hills year round, interpretation in this unit had to be done largely through nonpersonal devices such as trail brochures, bulletin boards, and outdoor exhibits. The NPS allocated most of its personal services to the Sheep Rock Unit, where uniformed staff provided interpretation on a regularly scheduled basis at the Cant Ranch and along some trails. Clarno received far less attention from interpreters than either of the other two units because of its distance from main travel routes, but park employees provided programs for students at Camp Hancock on an occasional basis after 1990. [40] These interpretive efforts, along with two mutual assistance agreements, served to back the claims made before the monument's establishment that the NPS and Camp Hancock could complement each other. [41] The small amount of actual park land and associated development in the Clarno Unit, however, has generally kept the NPS presence there to a minimum. [42]

|

| Camp Hancock, later Hancock Field Station, July 1977. (NPS photo) |

The NPS centralized its interpretive operations at the Cant Ranch by necessity. In being the monument's main visitor contact point, the ranch house provided a place to focus front line interpretation and nonpersonal services such as exhibits, audio-visual presentations, and cooperating association sales items. [43] Despite some advantage to centralization, a number of NPS employees found the historic ranch setting to engage visitors to the detriment of interpreting the monument's comparatively subtle paleontological story. In response, park crews periodically tried to reconcile what Ladd began to call an "interpretive conflict" by turning some of the outbuildings into exhibit or demonstration areas. [44] This occurred on a somewhat piecemeal basis without the benefit of a plan, and did not result in any clear separation between the monument's paleontology and history themes. [45]

|

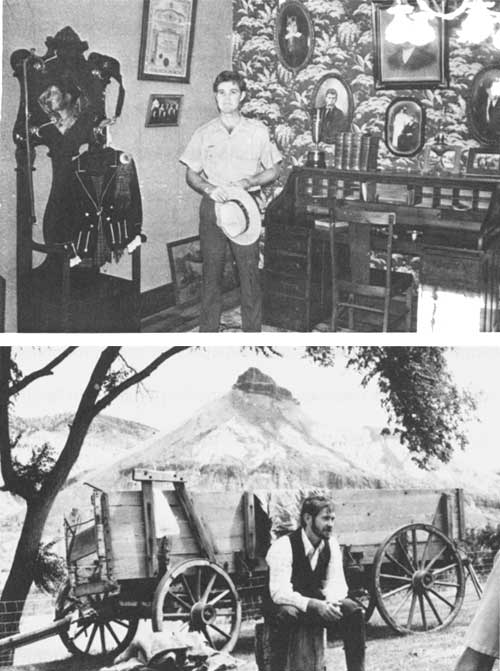

| The NPS did what it could to reconcile paleontology to the Cant Ranch setting. One room in the house interpreted the ranch story (top) while fossil exhibits dominated the main visitor contact area located across the hall. Interpreter Kim Sikoryak (bottom) portrayed naturalist Loye Miller (who accompanied the 1899 University of California Expedition) in a living history presentation which took place near the house during the summer of 1980. (NPS photos) |

Ladd called for site planning assistance after acting regional director William J. Briggle visited the park in 1986. [46] NPS personnel in Seattle subsequently drafted a task directive for the site plan, hoping that the document might guide the next 15 years of rehabilitation, adaptive use, and development of new structures and exhibits in or near the Cant Ranch complex. [47] A four member team formulated several recommendations in the plan. They assumed that budgetary limitations might allow the proposed Thomas Condon Visitor Center to serve only visitor orientation and interpretive center uses. As a result, associated functions such as fossil preparation, laboratory demonstrations, storage, research, and group seminars might have to remain at the Cant Ranch complex. [48] The team also suggested moving the vehicular entrance to the complex 300 feet further north. This allowed for more parking to be developed and better sight distance for motorists making the turn from State Highway 19. They stressed that a new entrance could also help visitors make a logical progression through the complex on foot once the NPS relocated its maintenance facilities from the ranch workshop to a new site west of the highway immediately opposite the ranch house. [49] Pedestrians might then go from the parking area to a prominent site orientation device. Once aware of their options, visitors could proceed toward exhibits and demonstrations which gave primary emphasis to paleontology. In recommending that the barn be used for this purpose, the team saw moving fossil preparation into the workshop as a logical complement. They also suggested that a research and education center be located on the ground floor of the ranch house, with NPS offices being upstairs.

In formulating this "logical progression" through the site, the team also made allowance for development of a self-guiding loop for interpreting ranch life. In its most basic form, the loop incorporated a display of ranch machinery on one side of the barn and a stop at some nearby sheep pens. [50] In addition, the team recommended using the screened porch of the ranch house to interpret ranching history. They also wanted consideration given to building a self-guiding trail along the John Day River which presented the story of pioneers and agriculture. As part of a larger circulation system, such a trail might provide visitors with access by footbridge to Sheep Rock. [51]

When their draft reached the Washington Office, NPS director William Penn Mott questioned the team's main assumption that functions associated with fossil resources had to be split between a proposed visitor center and the Cant Ranch. He could not understand why the proposed visitor center could not be designed to include exhibits, demonstration areas, and laboratory space. [52] Mott saw the ranch story as entirely separate and agreed with other Washington Office personnel that Denver Service Center planners could help the team determine the location and costs for a stand-alone visitor facility. [53]

Team members and representatives from the park met in Seattle almost a year later to review progress toward a final plan. They agreed to play down the draft's emphasis on rehabilitating the barn for interpretation, choosing instead to use it for fossil storage after stabilization work had taken place. The participants also wanted to address moving park headquarters to the Cant Ranch in the final plan, something which represented a new consideration. [54] Further progress on the plan halted once Ladd opted for the stand-alone visitor center in November 1988. [55] He still wanted to see if moving headquarters to the Cant Ranch complex might be feasible and asked for a formal evaluation to be conducted over the following year. [56]

Although the site plan never reached a stage where it could be finalized, the NPS implemented two of the team's suggestions. One had to do with signage and resulted in the design of new entrance motifs for the Sheep Rock Unit. [57] Park curator Ted Fremd formulated a plan to guide paleontological research at the monument in response to the team's observation that the degree, extent, and level of involvement in this activity needed to be addressed. [58] Planning for a new maintenance facility continued, but most of the issues the team raised did not receive further examination until Congress approved funding for preliminary design of the Thomas Condon Visitor Center in 1989. [59]

|

|

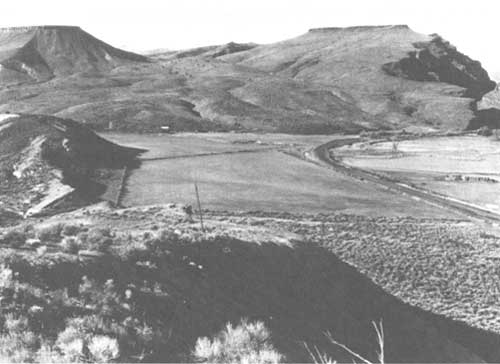

Private land on Rattlesnake Creek, south of Picture Gorge in 1981. This is Tract 101-07, which the planning team favored as a potential site for the monument's visitor center. (NPS photo by Jim Mack) |

That December the NPS selected a site for the visitor center across from the Sheep Rock Overlook, but west of State Highway 19. [60] Planning began anew despite previous efforts which took place from 1978 to 1980. At that time the NPS slated the facility to be built at the Sheep Rock Overlook and completed a preliminary design. [61] After shelving the project for lack of construction funds in 1980, the NPS did nothing to consider other sites for a visitor center until 1987. [62] At that point the team associated the Cant Ranch site plan with recommendations concerning several prospective locations for a visitor center along US 26 and State Highway 19, but indicated some preference for one south of Picture Gorge near Rattlesnake Creek. [63] Despite some initial interest in this and other alternative locations, the proposed visitor center remained at Sheep Rock Overlook for the moment because of concerns about having to acquire private land. [64] The overlook's small size and proximity to the Cant Ranch resulted in a subsequent shift in NPS attention across State Highway 19 to an adjacent site. [65] Sufficient space existed there to develop a facility visually separated from the Cant Ranch, while commanding a view of Sheep Rock so that visitors could focus on paleontology. Exhibit planning began as soon as the regional director signed a task directive for design of the visitor center. [66] Architectural drawings and other elements of the package, such as plans for site work, followed in 1991 and 1992 50 that actual construction could begin in 1993 or thereafter. [67]

|

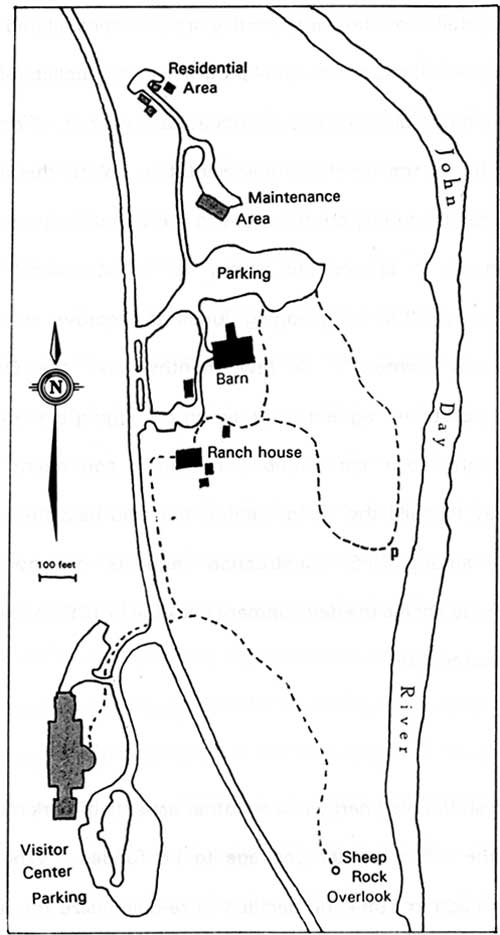

| Site plan, February 1993. Existing structures are shown in black and prospective buildings are shaded. State Highway 19 divides the visitor center area from Park Headquarters at the Cant Ranch; other roads and parking areas on the plan are proposed. Except for the trail from Sheep Rock Overlook to the ranch house, all of the trails (shown by dotted lines) are planned. The "p" indicated a future picnic area near the John Day River. |

From its outset, planning for the visitor center included Ladd's desire to move park headquarters from John Day to the Sheep Rock Unit. Planners initially had administrative functions housed in the visitor center, but park employees saw the ranch house as compatible with a headquarters office as well as continued public use in the form of picnicking and interpreting ranch life. [68] This led to another round of site planning for the ranch complex, primarily to study future rehabilitation options. This site plan, however, soon included design of a small residential area and locations for the proposed maintenance facility. [69]

Since the funds appropriated for visitor center design allowed for additional site planning at the Cant Ranch complex, the NPS rolled them into one development package. [70] Plans associated with it effectively updated the monument's GMP and DCP when the NPS released an environmental assessment in 1993. [71] The proposed action described functions and site improvements associated with a visitor center, removal of the road and parking area from Sheep Rock Overlook, as well as rehabilitation and new construction needed at the Cant Ranch complex. [72]

In a similar vein, completion of an interpretive prospectus in 1991 served to update the monument's interpretive plan. The latter had been formulated to support plans for a visitor center and the GMP in 1978, but did not supply sufficient direction for the NPS to produce interpretive media through its service center located in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. [73] Consequently, the prospectus provided more detail about how interpretive opportunities related to the content of possible wayside exhibits, audio-visual programs, and publications. [74]

Having updated planning documents in hand did not, of course, necessarily translate into the means for their implementation. With this in mind, the NPS encouraged state and county contributions to the visitor center project in hopes of prodding Congress to appropriate money for construction. [75] Grant County responded in early 1992 by pledging funds to improve road access to the prospective visitor center. [76] A few months later the Oregon Economic Development Department agreed to underwrite bringing electrical power to the site. [77] Although these contributions remained contingent upon Congress providing money to build the visitor center, they did help the project assume a higher priority among NPS construction requests nationwide. [78] Planners nevertheless had to shelve the development package in 1993 because construction funds did not materialize. [79]

Prospect

The NPS shifted its energy toward other aspects of park management while it waited for the visitor center package to be funded. When Jim Hammett succeeded Ben Ladd in 1994, he decided to re-emphasize the monument's land protection goals especially in the Sheep Rock Unit. [80] This focus appeared to pay some dividends in late 1995, when long-running negotiations for fee acquisition of the Mascall Overlook seemed to be successful at last. [81] The deal may bode well for addressing other priorities, such as obtaining the Maurer tract at Clarno, but the NPS still has some distance to travel before all of the fossil-bearing formations represented within the monument's authorized boundaries are effectively protected.

Hammett continued, however, to support paleontology as the main focus of NPS resource management efforts. While he also attended to neontological and cultural concerns, this outlook helped to ensure that NPS operations did not begin to wander off track in a park established primarily for its paleontological values. [82] Correspondingly, Hammett embraced procedures institutionalized by Ladd which aimed at identification and study of resource values before management actions such as construction of park facilities took place. This method of operation, in conjunction with the prevailing pattern of visitation, has allowed the NPS to minimize tension between preservation and visitor enjoyment of the monument.

A long-standing decision not to duplicate services available in the local communities also contributed to lessening impacts associated with use of the park. This direction has had the advantage of so far removing the need to obligate funds for regulating concessions or operation of campgrounds. The lack of overnight facilities on the monument has restricted some types of interpretation, such as evening slide programs, but compensation in the form of visitors having an opportunity to receive individual attention from NPS employees at the Cant Ranch somewhat offsets this limitation. Nevertheless, "interpretive conflict" there between a setting dominated by ranching and the story represented by the monument's Paleontological resources, continues to negatively impact how well park staff reach visitors. [83]

Such problems, however, should not detract from the contributions made by the NPS throughout this part of Oregon. Park staff have taken an active role in public education and demonstrated how one small part of the National Park System could emerge as a leader in resources stewardship. Their integration with surrounding communities demonstrated that these achievements did not have to come with the continuing costs associated with maintaining a residential compound composed entirely of NPS employees and their families. Instead, the administrative history of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument testifies to how the concept behind John C. Merriam's parkway proposal could work, but in a form that he never quite anticipated.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002