|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Six:

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

The National Park Service began to take an active approach to managing the monument's paleontological resources in 1983, when Superintendent Ladd opted to keep specimens recovered from the park on site. Subsequent establishment of a museum technician position eventually led to a cooperative agreement with the Bureau of Land Management, something which had the NPS providing curation for fossils obtained from federal lands throughout the upper John Day Basin. This pact represented one way in which monument staff took an increasingly aggressive role in facilitating scientific research, thereby allowing the NPS to better fulfill its statement of the park's purpose.

The paleontology program s expansion and rising credibility represented an enormous change from 1978, when resource management efforts could be described as being in their infancy. Neontological (modern plant and animal) and cultural resources management meanwhile struggled to become custodial over the following 15 years. All three programs benefited from increased funding that allowed for contracted studies and, in a couple of instances, additional staffing.

Paleontology

Ladd observed near the end of his superintendency that the general management plan approved in 1979 suffered from being too narrow in scope and attributed this flaw to the NPS not knowing enough about the monument's resources. [1] Although the GMP gave center stage to paleontology in resources management, it focused largely on in situ protection of fossils on park lands. This stemmed from the planning team wanting to comply with general NPS policy. In doing so they sought to prevent unauthorized disturbance of the park's paleontological resources and allowed only qualified investigators to collect through a permit system. One sentence in the GMP constituted the sole reference to collections, and that made an open-ended reference to repositories where specimens could be made available to scientists for study. [2]

In 1978 Ladd and other members of the planning team envisioned a relatively small on-site collection. This resulted from the monument having limited storage space and the uncertain availability of professional expertise for collecting, preparing, and identifying specimens. [3] Rather than add a paleontologist to his staff at this point, Ladd chose to contract with the cooperative park studies unit (CPSU) at Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis for needed services. [4]

Since fossils could be exposed near existing trails such as the one in Blue Basin, Ladd saw their potential as exhibits. [5]This led to the NPS contracting with the CPSU for the location, relief, and preparation of fossil exhibit material beginning in 1979. [6] Largely through the efforts of OSU paleontologist John Ruben, three specimens had been recovered and prepared for display at the Cant Ranch by the end of 1980. [7] Over the following year, Ruben and a colleague from the University of California at Riverside, Hugh Wagner, began to improve locality information associated with recovered specimens by initiating a grid system for mapping fossil locations in the park. [8]

|

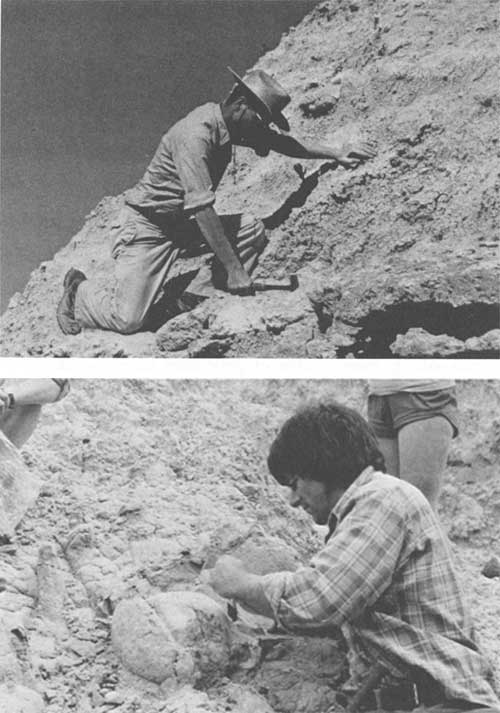

| John Rensburger (top) and John Ruben (bottom) gave the NPS needed information about the monument's paleontological resources. (NPS photos) |

With a mapping system in place, Ladd felt that Ruben should produce a plan to guide what might be collected and retained at OSU. When Ruben failed to produce such a plan, Ladd changed his thinking in regard to keeping collections at the monument. [9] The NPS then moved to acquire fossil preparation and storage equipment, with establishment of a permanent museum technician position taking place by the end of 1983. As part of his justification for the position, Ladd folded it into the ongoing adaptive rehabilitation of structures at Cant Ranch. He therefore arranged to use a log cabin located in back of the main ranch house to serve as a demonstration exhibit where fossil relief work could be performed in front of visitors. [10] Further justification came from a collections management plan written under contract in 1984, which described specific problems associated with the monument's museum records and care of its collection. [11]

Ladd selected Ted Fremd to fill the museum technician position. Within a few months of his arrival from Fossil Butte National Monument in July 1984, he had completed most of the accession backlog. [12] Fremd's training in paleontology also allowed him to play an important role in field prospecting and fossil recovery. [13] This allowed the NPS to terminate the CPSU contract for survey and recovery of exposed fossils, thereby reassigning those tasks to park staff. [14] Consequently, the park's collection grew from approximately 300 objects in mid-1984 to 1,500 over the next two years. [15]

|

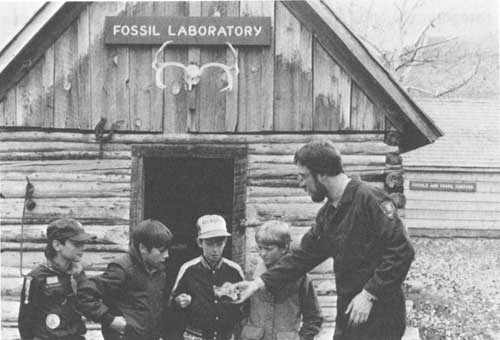

| Ted Fremd shows a specimen to young visitors, March 1985. (NPS photo by Kim Sikoryak) |

Fremd revised the monument's scope of collections statement while this first growth spurt took place. Approved in January 1986, the document separated paleontological objects into an exhibit series and a research study series. In the former category, the NPS wanted to have one fossil specimen representing each plant and animal species occurring in the monument's rock formations. The research study series, by contrast, could contain all fossils collected by qualified investigators within the monument's boundaries. It might also include specimens collected from outside the park, as long as retrieval took place from geological deposits similar in age to those represented in the park or local depositional environments. This provision came from Fremd and other paleontologists having recognized the fact that the full breadth of the park's story could not be told within the monument's boundaries. He also made the point that museum catalog records, specimen labels, and associated field data for all fossils collected in the area before the monument's establishment constituted legitimate additions to the research study series. [16]

As intended, the revised scope of collections statement set general goals and limits for maintenance of the museum. It also helped to give the paleontology program momentum, or at least justification, for an aggressive approach to collection and documentation of all fossil material found in the field. By 1986 Fremd and other park employees actively assisted investigators representing a number of institutions with work in all three units of the monument. The museum collection benefited from this work by gaining a number of additional fossil specimens, some of which came from outside the monument's boundaries. [17]

A dramatic increase in the number of specimens coming from outside park boundaries resulted once the NPS and two Bureau of Land Management (BLM) districts signed a cooperative agreement (see Appendix B) in 1987. In order to promote better management of paleontological resources occurring on federal lands in the John Day Basin, the NPS agreed to provide technical expertise to the BLM as well as curation and accountable storage for retrieved specimens. In return, the BLM assented to allowing authorized NPS employees to collect fossils on public lands in the Prineville and Burns districts. The BLM also agreed to provide financial and logistical support for its specimens stored with the NPS museum collection. [18] Fremd touted the pact as a model for partnerships in paleontological stewardship soon after it went into effect. He noted that over 500 specimens from BLM sites had been identified and curated by park staff in only one year. The BLM, in turn, purchased storage equipment and helped to defray the salary of a temporary museum technician. [19]

An expanding horizon in collecting and curation coincided with more concerted efforts by park staff to obtain information about fossil specimens from the John Day Basin housed in other repositories. Fremd began inventorying this material by visiting institutions in Oregon and Washington during 1987. [20] Review of specimens and related records widened somewhat that year when interpreter Kim Sikoryak accepted a three month detail in Washington, D.C. Long-time volunteer Jane Sikoryak responded to this opportunity by compiling a report on park-related collections at the Smithsonian Institution, National Archives, and Library of Congress. [21]

In early 1988 Ladd described the monument as "uniquely positioned to serve as a bridge between science and the general public." [22] Since Fremd and other park employees wanted to build stronger links to academia in order to improve resource management and interpretation, the NPS found it advantageous to prepare a research plan. Written by Fremd and approved by Ladd in February 1989, the plan aimed at assuring continuity in the monument's research program by providing the means to evaluate proposals. [23] It also represented a vehicle to communicate opportunities for study by outside investigators, so Fremd emphasized the monument's research needs and delineated how such work could be accomplished. [24]

Since coming to the park in July 1984, Fremd's position gradually expanded from a largely curatorial one to include the research aspect of paleontology. In early 1988 he began a long-term study of fossilized Turtle Cove fauna aimed at resolving the problem of depositional history in the John Day Formation during the early-middle Miocene. [25] Ladd responded by revising the organizational chart so that Fremd could report directly to the superintendent rather than the monument's chief interpreter. [26] Fremd's expanding role in research and an annual growth rate of 500 or more objects in the museum collection necessitated additional staff support for the curatorial function. [27] Once Ladd found funding from a vacant park ranger position, the NPS added a permanent museum technician in 1989. Working mainly as a preparator under Fremd who now served as the park curator, Camille Evans filled the new position. In addition to bringing better care to a growing fossil collection, her presence also allowed the NPS to generate additional exhibit specimens and permitted a greater number of exchanges with other institutions. [28]

Throughout this period Fremd continued to visit known localities within the park at least once a year as part of a cyclic prospecting system. [29] Since hazards to fossils from weathering and breakage increased significantly once exposed at the surface, he spent at least 25 percent of his time surveying places where easily eroded volcanic tuffs yielded specimens on a regular basis. [30] Upon retrieval of each find, park staff entered information concerning specimens into a database with detailed coordinates. This made it possible to find data on all specimens collected from a small geographical area or within a stratigraphic interval. Fremd also noted the benefit of being able to reunite faunal samples, microinvertebrate assemblages, and even individual organisms separated by different collection episodes through use of this system. [31]

Better locality information available through the database contributed to periodic collection surveys of specimens obtained in the John Day Basin but held by other institutions. Fremd visited the University of California at Berkeley in 1989 and 1991 to photograph and document specimens of interest to the NPS. [32] He also traveled to the University of Oregon to study paleontological holdings there, something which also included negotiations over allowing the NPS to borrow specimens from the Thomas Condon collection. [33] In 1992 Fremd and park volunteer Skylar Rickebaugh went further afield by conducting surveys at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Peabody Museum at Yale University. [34]

Along with a comprehensive literature review, the collection surveys represented an important aspect of a research process described by Fremd as critical for curation of specimens in NPS care. Another aspect of that process involved facilitating needed studies so that time and stratigraphic relationships among specimens could be better understood. [35] In Fremd's view, mapping the stratigraphy of the Painted Hills and Clarno units constituted the top priority among all proposed research because it could establish a geological framework for evaluating the significance of fossil resources located in that part of the monument. [36] Once a three year contract for the mapping began in 1991, investigators found a number of new localities and provided the NPS with associated specimens. [37] The contract's success led directly to another one for stratigraphic work in the Sheep Rock Unit, this time in the Mascall Formation's type area. [38]

Even with much of the geological framework established for the monument's fossil resources, Fremd maintained that determinations of significance often rested with more than one branch of paleontology. As a vertebrate paleontologist, he recognized the need for active consultations with other specialists representing paleobotany, invertebrate paleontology, stratigraphy, geochemistry, and paleopedology. [39] With active investigations in the park area numbering more than ten by 1992, Fremd initiated a revival of the John Day Associates primarily as a way to facilitate better communication among these workers. [40] It proved popular enough to attract 40 members in just three years, mainly because Fremd could act as an on site facilitator. [41]

Despite all of the interest from outside investigators in a revived John Day Associates, Fremd stressed that the NPS still had to develop suitable facilities to take advantage of low cost professional help. This consisted of living quarters to offset the independent researcher's cost of rendering assistance, as well as use of equipment in a laboratory large enough to permit year round work by staff, volunteers, and visiting scientists. [42] Little progress toward the provision of such housing had been made by 1995, but the paleontology program registered some gains in regard to work space over the previous five years. Conversion of the Cant Ranch bunkhouse into a fossil preparation laboratory took place in 1990, something which relieved cramped conditions in the log cabin devoted to demonstrating relief work. [43] The program gained more space in the main ranch house for accession storage in 1992, while also obtaining use of a free-standing storage shed inside the Cant Ranch barn for part of the museum collection. [44] Construction of a Bally building inside the barn two years later resulted in a larger and more permanent storage area for a museum collection which, at this point, totaled almost 10,000 objects. [45]

Neontology

In contrast to the paleontology program, management efforts associated with modern biota (as opposed to that represented in the fossil record) have remained relatively small in scope. Even so, they have been supported by a fair amount of research contracted mainly through the cooperative park studies unit at Oregon State University. Most of the studies focused on vegetation, largely because it could provide the basis for restoring some semblance of presettlement wildlife habitat to lands impacted by grazing and other agricultural practices since the 1860s.

While the NPS acknowledged that land use and management actions outside of park boundaries probably had greater influence on wildlife than what took place within the monument, it still wanted to maintain populations at levels consistent with the carrying capacity of less modified habitats. [46] This aim, however, could not be attained as long as the monument lacked adequate wildlife surveys or systematic monitoring to determine population changes over time. [47] The small amount of research simply served to allay fears by ranchers in Sheep Rock Unit that the park provided a refuge for excessive numbers of deer and coyotes. A CPSU study completed in 1980 recommended population densities of either animal did not warrant active control measures. [48] Consequently, no actions to control large mammals have taken place on park land and the NPS took only limited measures to check rodent damage which occurred in the monument's developed areas. [49]

A sustained effort to enhance riparian vegetation in and near these developed areas necessitated the small amount of rodent control undertaken by park staff. Bank stabilization, however, constituted the first step toward riparian enhancement, something which the NPS began in 1980 by planting juniper along Bridge Creek at Painted Hills. [50] Serious channel erosion and undercutting of banks along more than two miles of this stream threatened the picnic area and access road, so the NPS responded with placement of rip-rap, rock jetties, and native vegetation along the creek over the next five years. [51] Ladd observed dramatic improvement along Bridge Creek by 1991, observing that beaver had constructed four large dams and one lodge within a half mile of the picnic area. [52] He also noted that the park's apparent success furnished an example which the BLM wanted to emulate in other areas along the creek because similar projects could enhance spawning conditions for native steelhead trout. [53]

A pressing need for bank stabilization and reestablishment of riparian vegetation on the John Day River within the Sheep Rock Unit drew the attention of park staff beginning in 1983. Severe erosion affected 1,000 linear feet of riverbank associated with Cant Ranch bottomland which the NPS hoped to lease for the production of hay. Stabilization started with 100 yards of rip-rap so that an irrigation ditch could be replaced by a pump lift station. [54] Rock jetties and more rip-rap became necessary by 1985 because banks continued to erode, causing a substantial loss of topsoil each year. [55] In response, park employees planted cottonwood, choke cherry, and willow on a continuing basis to help reestablish riparian habitat along this part of the river. [56]

Revegetating riparian areas represented only one facet of what the NPS hoped to accomplish in managing for more natural plant succession. From 1977 onward, park staff took active measures to control noxious weeds which proliferated in previously grazed or heavily disturbed areas. [57] The NPS also utilized CPSU studies for guidance on how to revegetate former rangeland on the monument with native species. [58] A study that began in 1987 showed prescribed fire to be a potentially effective way to restore balance between depleted native bunchgrasses and overly abundant woody plants such as western juniper and big sagebrush. [59] Bunchgrasses and forbs could thereby reclaim burned areas where the woody plants formerly dominated because of fire exclusion and grazing. [60]

More proactive approaches to vegetation management required a monitoring program, whether such actions took the form of seeding native plants or experimental use of prescribed fire. Two contracted studies completed in 1992 helped park staff measure change in upland vegetation and sensitive plants, since both employed comparisons with a 1977 study of the monument's plant communities. [61] To better coordinate the monitoring program with future efforts by park staff, Ladd hired the monument's first natural resources management specialist. Ken Till, formerly one of the research assistants connected with the CPSU studies on prescribed fire, started work in January 1992. [62]

A vegetation management plan, which might allow the NPS to better incorporate the beneficial effects of fire on native species composition, soon became Till's biggest project. [63] It remained unfinished by the time he transferred more than three years later, but assessments of plant community types in relation to predicted fire effects could be downloaded into the monument's geographic information system. [64] Till completed smaller-scale rehabilitation plans aimed at recovery of native bunchgrasses and forbs on park acreage affected by wildland fires. [65] Without a vegetation management plan in place, however, the NPS had little justification for increased staff and funding to implement prescribed burns on a programmatic basis. [66]

Cultural

The Cant Ranch complex dominated cultural resources management before and after approval of the monument's GMP in 1979. Despite it containing language urging maintenance of "a ranch scene spanning three-quarters of a century," the GMP stated that none of the park's buildings and structures met criteria for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. [67] This state of affairs changed abruptly in late 1982, when termination of the livestock operation at the Cant Ranch coincided with issuance of NPS guidelines on leasing historic properties. [68]

Some 74 acres of irrigated hayland held the potential for continuing agricultural use on a lease basis, thereby maintaining part of the ranch scene, while also allowing the NPS to defray the cost of rehabilitating the bottomland. [69] Since granting any such lease had to be preceded by a National Register listing, Ladd thereby sought this designation for the Cant Ranch. [70] Revision of the monument's List of Classified Structures in mid 1983 began the process. This changed the eligibility of 12 buildings associated with a 200 acre Cant Ranch "complex," something which also included the prospective lease along with other bottomland upstream almost to Picture Gorge. [71] NPS regional historian Stephanie Toothman subsequently drafted a National Register nomination which placed all remaining ranch structures, ditches, and irrigated fields in a 200 acre historic district as of June 21, 1984. [72]

The National Register listing allowed an almost concurrent issuance of a lease for the 74 acres of irrigated hayland. In being only the second lease completed by the NPS under its new-found authority, Toothman found it to furnish an enlightening case study of how to handle similar agricultural properties. [73] Revenue generated from annual leases over the first three years went toward renovating hay fields and irrigation ditches so that a longer term lease became feasible. [74] A four year lease on three fields took effect in 1987, with it being reissued to the same lessee for an additional eight years in 1991. A multi-year term lowered the government's administrative costs and seemed to provide additional incentive for the lessee, but a lack of interest plagued the arrangement. [75] Park staff attributed this to a combination of factors which included isolation of the fields from other agricultural operations, the irrigation system's deteriorated condition, and a perception of unreasonable restrictions on leased land. [76]

Although results associated with the leasing program had been somewhat disappointing, the fields remained an important part of the historic district. In response to a need for information about past use and appearance of the fields, the NPS funded an in-house cultural landscape report on the historic district beginning in 1993. [77] This study sought to define landscape features, patterns, and relationships which contributed to the district's character so that potential impacts of new development on the site could be assessed. [78] More specifically, this meant delineation of historic periods for the landscape and identification of existing features related to those periods. Recommendations could then follow for how to manage agricultural land, orchard trees, and ornamental vegetation associated with the ranch house. [79]

Park staff also sought guidance on how to maintain and preserve the ranch buildings once they became part of a historic district. A contracted historic structures preservation guide completed in 1986 originated from concerns about the barn's structural integrity and changes brought by adaptive use of the ranch house. [80] These two buildings became the focus of a Historic American Buildings Survey documentation project which produced measured drawings as well as narrative on their history and architecture. [81] A decision by Regional Director Charles Odegaard in 1991 to make the ranch house serve as park headquarters led to funding for a structural analysis of the building. Measures to reduce the weight load on upper floors followed from the analysis in 1992, even though the NPS did not move headquarters from John Day until two years later. [82]

|

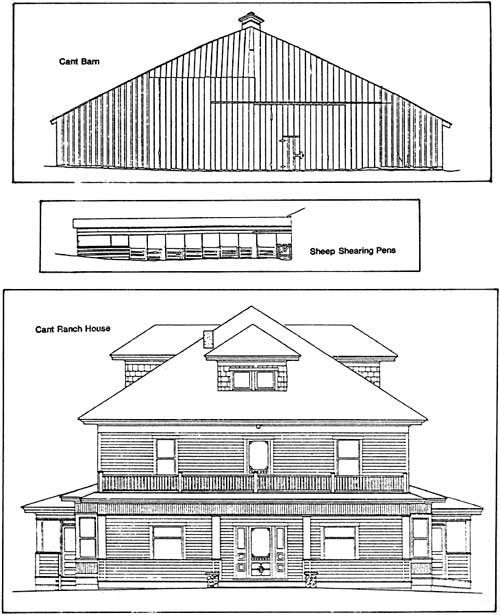

| Measured drawings of structures at the Cant Ranch, 1984. |

As representative of early 20th century agricultural development in this part of Oregon, the 200 acre Cant Ranch Historic District gave ranching a conspicuous place among historic themes represented at the park. Other themes (such as the Indians of north central Oregon, entry and settlement by homesteaders, historic transportation corridors, and 19th century paleontological exploration in the John Day Basin) commanded comparatively little attention from park staff, mainly due to the lack of baseline information. Without the guidance of a historic resource study, little was accomplished in preserving resources related to these other themes. [83]

Despite this shortcoming, the NPS found itself able to provide some assistance to local preservation efforts for the Kam Wah Chung Museum in John Day. The former store building had been loosely associated with the monument since 1967, when one member of the NPS study team suggested it be incorporated as part of park headquarters. [84] That year Gordon Glass began to inventory its contents, though formal restoration efforts did not begin until the city obtained funding for a feasibility study in 1972. [85] After the store's listing on the National Register in 1973, the NPS and Oregon State Parks provided a total of $60,000 in funding so that the city could open it as a museum four years later. [86] Concerns from Glass and others about long term care of the site led to a request in 1992 that the NPS conduct a study of preservation alternatives. [87] The study remained unfunded through 1994, but acting superintendent Jim Morris participated in planning for future operation of the museum in conjunction with other interested parties. [88]

Management of the monument's archeological resources largely took the form of limited ground survey during the course of developing park facilities. [89] Most of the terrain in all three units has not been systematically surveyed, though a contracted document in 1993 supplied general direction for future research, interpretation and management. [90] Efforts aimed at protecting pictographs in Picture Gorge constituted the main thrust behind management of the monument's prehistoric sites due to potential harm from graffiti and bird droppings. As a first step, the NPS funded a conservation survey of the pictographs in 1985. [91] It fell short of comprehensive inventory and analysis of their significance, but park staff did make subsequent efforts to remove some graffiti and discourage nesting near the drawings. [92]

|

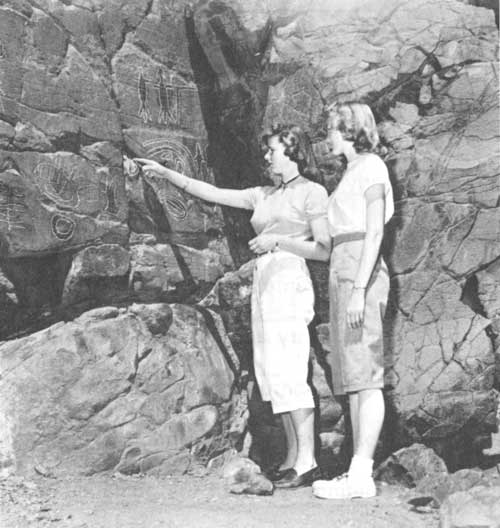

| Visitors examining rock art in Picture Gorge, about 1955. (Oregon State Highway Division photo #5242) |

The pictographs also provided an initial focal point in the development of formal procedures for tribal consultation. This started in 1990, when Ladd requested an ethnographic study of the monument after being informed that tribal members on the Warm Springs Reservation considered the pictographs to be spiritual objects. [93] The study had not materialized two years later, but the NPS contacted tribal governments for the three closest reservations to the monument. Representatives of each (Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Burns Paiute) wished to develop ongoing consultations about management of cultural resources with heritage value for the tribes, future developments at the park, as well as the documentation and interpretation of tribal histories in the John Day Region. [94]

|

| US 26 in Picture Gorge about 1965. (Oregon State Highway Division photo #7110) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002