|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Five:

LANDS

Of the 14,030 acres authorized for acquisition at the time Congress revised the monument's boundaries in 1978, just over 4,200 acres remained in private hands. Since the legislation allowed for an additional $3.5 million for land acquisition, the NPS could begin a concerted effort to obtain both fee title and scenic easements from property owners in all three units. This resulted in the NPS obtaining several important parcels by 1982, but negotiations for the remaining top priority tracts stalled over the following decade because of a management emphasis on land exchanges, rather than cash, as payment.

Acquisitions did not constitute the sole thrust of NPS dealings with its neighbors. Completion of a project to fence contiguous federal lands in 1986 alleviated much of the mutual concern about trespass grazing In addition, maintaining the monument's natural and pastoral setting required the NPS to be periodically involved with land use actions, whether questions arose over water, land partitions, or road locations.

Acquisitions after 1978

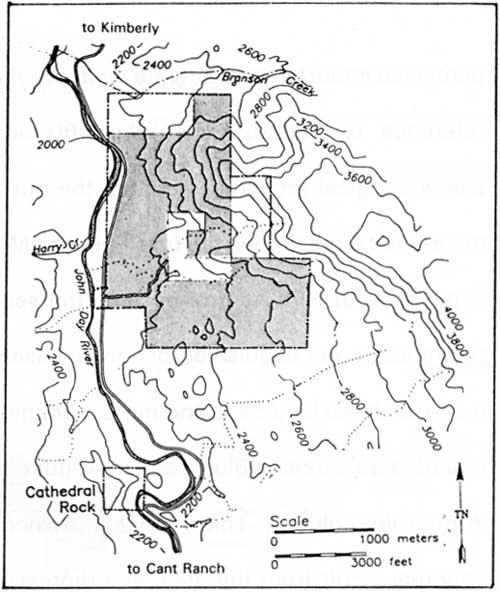

Negotiations for sale of land at Foree could be completed once Congress the 1,000 acre ceiling on fee acquisition in 1978. Bernard O'Rourke had died, so his widow sold 673 acres to the NPS in late 1979. [1] This resulted lifted since in the NPS gaining virtual control of Foree, something which came with a large trailer that could be used for employee housing. [2]

|

| Foree area of the Sheep Rock Unit. The shaded area represents Tract 102-03 obtained from O'Rourke in 1978. (from Burtchard, et al., Archeological Overview and Assessment, 1994) |

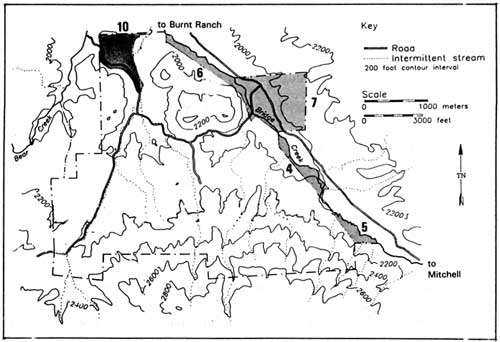

Finalization of a land exchange with Brooks Resources came in May 1980, and represented something which greatly aided NPS management of the Painted Hills Unit. The company received a deed for 38 acres of formerly NPS land so they could proceed with a water impoundment. [3] They also obtained a clarified easement for access to their land west of the park on an existing road. In return, the NPS acquired land along Bridge Creek and received other compensation. [4] The land consisted of three tracts totaling 83.60 acres in fee and a 200 acre scenic easement. [5] An important part of the agreement centered on Brooks Resources abandoning a stock driveway through the park which previously prevented the NPS from fencing its boundary. Company president William L. Smith granted an easement so as to allow the NPS to hide its boundary fence from the view of park visitors and agreed to provide the government with access to the impounded water so that the picnic area at Painted Hills could be irrigated. [6] The company also gave Wheeler County a scenic easement on its lands along a six mile stretch of road which connects US 26 with the park. [7]

|

| Land exchange with Brooks Resources in the Painted Hills Unit, 1980. Tracts 103-04, 103-05, and 103-06 totaling 83.60 acres were obtained by the NPS in fee, while the 200 acre Tract 103-07 was a scenic easement. The 38 acres in Tract 103-10 was acquired by Brooks Resources in fee simple. (derived from Burtchard, et al., 1994) |

Both the Foree and Painted Hills transactions had been mentioned as priority acquisitions in the monument's general management plan (GMP), as approved in 1979. [8] The GMP, for the most part, lacked further specifics about how the NPS anticipated obtaining other private lands within the monument's boundaries. A land acquisition plan approved in April 1980 provided a first step by separating the perceived importance of private land into three categories. The first made specific reference to Clarno, where the 960 acre Maurer tract contained important paleontological resources such as the nut beds and mammal quarry. A need to have lands representing the fossil-bearing Mascall and Rattlesnake formations under some form of NPS control became the second category. The third simply made reference to fee acquisition or scenic easements being the methods used to form a consolidated land base and more manageable contiguous units. [9] Fee acquisition of a 55 acre parcel at Blue Basin in August 1982, for example, was thereby classed in the third column. This change in ownership at Blue Basin also constituted the only real result from the plan, and represented the last NPS land purchase within the monument's authorized boundaries for more than eight years. [10]

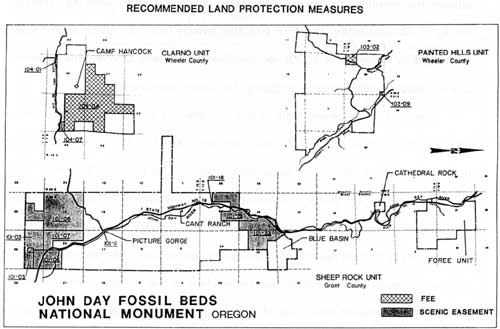

A subsequent land protection plan (LPP) for the monument resulted from a Department of the Interior policy statement regarding use of Land and Water Conservation Fund monies for acquisitions. [11] The plan, as approved in February 1984, focused on identifying options other than fee acquisition of private lands and established specific priorities for obtaining parcels in each of the three units. After placing the park's purpose in context with land ownership and compatibility of uses, the NPS thereby eliminated cooperative agreements and zoning as viable land protection alternatives. After justifying its reliance on scenic easements and fee acquisition, the NPS then placed its emphasis on land exchanges as the recommended means of conveyance. NPS staff reasoned that this approach kept land in production and on tax rolls, while noting they still had 720 acres of land outside the monument's revised boundaries which could be used as "trading stock." [12] Consequently, the NPS priorities (which had not shifted from those delineated by category in 1980) for the Sheep Rock and Clarno units showed almost exclusive reliance upon exchange for future acquisitions. [13]

|

| Recommended land protection measures, 1990. Tract 104-04 in the Clarno Unit is the Maurer parcel containing the nut beds and mammal quarry. Tract 101-03 in the Sheep Rock Unit represented another high priority for the NPS, where it sought a combination of fee acquisition and scenic easement around the Mascall Overlook. |

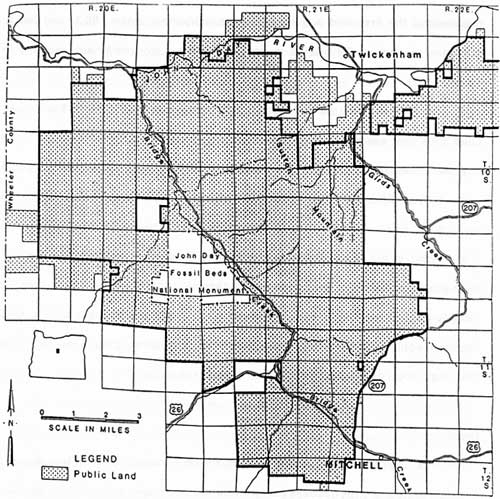

The first major amendment to the monument's LPP took place in 1990. Although its priorities shifted very little from the ones of 1984, the NPS modified the recommended means of acquisition from "exchange" to "purchase" or "purchase/exchange" for the 15 tracts it still hoped to obtain. [14] This constituted a belated acknowledgment that, in many instances, purchase represented the most feasible way to protect resources and provide public access. The plan also noted, however, a major land exchange had taken place in the vicinity of Painted Hills whereby BLM obtained lands east of the county road which approaches the unit from US 26. [15] Despite BLM's apparent success, the NPS experienced only frustration in using exchange as an inducement for landowners to part with key tracts in the Clarno and Sheep Rock units even though negotiations began as far back as 1980. [16]

|

|

A 1986 map of the proposed Sutton

Mountain Land Exchange between Brooks Resources Corporation and the Bureau of Land Management. Most of the exchange had been completed by 1990 and resulted in federal ownership of most land adjacent to the Painted Hills Unit. |

Even with the LPP recommending purchase as a method of acquisition, land transactions still required the fortuitous combination of willing seller and available funds. Sometimes a perceived threat had to precede acquisition, as in 1990, when some land owners in the Sheep Rock Unit wanted to partition almost 300 acres located a short distance north of the Cant Ranch. [17] As a result, the NPS bought 154 acres from Bob and Virginia Humphreys several months later. [18] This represented the first land acquisition at the monument since 1982, and led to purchase of another 139 acres in scenic easement from the same owners in 1992. [19]

The NPS still wanted to consolidate the Sheep Rock Unit's land base when Ladd's 18 year superintendency ended with his retirement in late 1993. Several key parcels located along the unit's southern edge, as well as tracts that could serve to join Blue Basin with the bulk of existing parkland, have yet to be acquired. [20] In all, the NPS still needed to have some level of control on roughly 1,808 acres in the Sheep Rock Unit while only 50 acres at Painted Hills had not been protected by either fee ownership or easements. [21] More than 989 acres (or roughly half) of the Clarno Unit, however, remained in private hands. The NPS therefore could not consolidate the disjunct federal holdings there until such time that acquisition of the 960 acre Maurer tract takes place. [22]

Grazing

After the monument's establishment, the NPS found itself with few ways of avoiding problems with trespass cattle on former state park lands without positive boundary identification and adequate fences. [23] Since the prospective land exchange with Brooks Resources gave the NPS a chance to consolidate control of Painted Hills, it completed a boundary survey for this unit in 1977. [24] A fencing project followed once the exchange had been finalized three years later. NPS employees built over nine miles of fence by the end of 1980, an undertaking which included removal of roadside fences constructed by the state. [25] Additional protection resulted from a cooperative agreement with Brooks Resources in 1982 to fence the east side of Bridge Creek. [26] Completion of the Painted Hills project came the following year, when the NPS built the final four miles of fence. [27]

Placement of fences in the Sheep Rock Unit began once the NPS obtained a parcel connecting the parking for Blue Basin with donated state park acreage. This project consisted of constructing two miles of fence around Blue Basin in 1983. [28] The NPS then moved to survey and fence Cathedral Rock and Foree through BLM in 1985. [29] Completion of fencing approximately ten miles on the east and west sides of the Sheep Rock Unit proper in 1986 effectively closed most of the contiguous park lands to trespass grazing. [30] That year the NPS also built one mile of fence at Clarno, something which Ladd described as excluding livestock from most of the unit. [31]

Five grazing leases inherited from BLM at the time of the monument's establishment posed few complications, especially since their number fell to two by the end of 1979. [32] Both of them were located in the Sheep Rock Unit and remained active throughout the 1980s. Their impact on park lands, however, remained relatively slight. Most of the calculated usage took place on a 640 acre tract that the NPS called "trading stock" located east of the monument's revised boundary near Picture Gorge. [33]

Land use actions

For the most part, none of the dealings with park neighbors over land use resulted in any difficulties for NPS management of the monument. Nevertheless, water, land partitioning, and road location issues had potential to establish compelling precedents. By the same token, congenial resolutions to these questions can create goodwill between the NPS and land owners located within and adjacent to the monument. One example centered on a water well that the NPS drilled at Clarno in 1982. [34] A water shortage at Camp Hancock in 1988 brought about an agreement whereby the NPS shared its water, though this came with one stipulation. In granting the camp a 20 foot right of way for its water lines, the NPS reserved priority usage for its picnic area should those facilities expand. [35]

In recognizing water availability as a limiting factor for park facilities, Superintendent Ladd took care to have all of the monument's springs inventoried in 1978. [36] Over the following 15 years, only one situation involving a park neighbor's use of a spring located on federal land within the monument arose. [37] An adjacent landowner, Frank Asher, successfully quieted title on an easement in 1989 that allowed him to construct a waterline from some springs located south of the Foree picnic area. [38]

Asher's acquisition of the easement came after he successfully petitioned in 1987 for part of his sheep and cattle ranch to be rezoned for development of a recreational vehicle campground . [39] The NPS supported Asher's application for the campground because it had the potential to provide overnight facilities desired by park visitors. [40] Given the absence of any such NPS development in the Sheep Rock Unit as projected in the GMP, Ladd could welcome a 20 unit campground located just outside the monument's authorized boundaries. [41]

Ladd did not, however, support the partitioning of similarly situated private land in the Clarno Unit. In that instance, the application arose from a landowner's desire to move a house trailer onto a 20 acre parcel zoned for exclusive farm use. [42] The NPS objected to any compromise of the monument's scenic quality, especially since the tract's location along State Highway 218 is within a half mile of the Clarno Palisades and picnic area. [43] After unsuccessful applications in 1985 and 1987, the landowner brought up the possibility of working out a land exchange with the NPS but with no immediate results. [44]

No road location issues have yet surfaced at Clarno, though moving an existing route at Painted Hills remains a long-term prospect. This will only occur if the water impoundment built by Brooks Resources reaches such a height where it inundates an access road to a neighboring ranch. [45] Since the company agreed to construct a new road on private land at its expense, Ladd assured the affected landowner in 1983 that no plans existed to move the existing route or even consider such a relocation. [46]

The state's proposed rerouting of US 26 to the south of Picture Gorge, however, represents potential impact on important fossil resources. [47] Preliminary talks among state highway officials, county representatives, and the NPS took place in March 1993 about an alternative whose implementation might affect exposures in the Mascall and Rattlesnake formations. The group acknowledged that if a new route through the Sheep Rock Unit is considered, then at least one alternative outside the monument has to be presented with justification provided as to the reasonable and prudent purposes for going through the park. [48] At that point county representatives willingly backed the NPS position on project alternatives, but urged monument staff to clearly express their views to the state. [49]

A more benign project from a NPS standpoint involves a realignment of State Highway 19 near Cathedral Rock. This proposal first surfaced in 1991 and involves a new route to eliminate congestion caused by pedestrians and vehicles on a blind corner. Ladd supported the idea, something which may allow the NPS to develop a wayside exhibit near Cathedral Rock once it obtains a portion of the abandoned highway for access to the viewing area. [50]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002