|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Four:

FORMATIVE YEARS: NPS ADMINISTRATION, 1975-1978

Once authorization of the monument took place in October 1974, its administration entered a formative phase. In establishing a National Park Service presence in the upper John Day Basin, the agency concentrated on developing a staff and protecting fossil resources with a low-key, educational approach. Upon completion of basic visitor facilities in 1978, Park Superintendent Ben Ladd considered it to be the first year that the monument functioned as a fully operational unit of the National Park System. [1]

A prototype planning process accompanied these efforts, paralleling efforts to acquire and rehabilitate prospective administrative facilities at the Cant Ranch. The planning process also gave impetus to legislated boundary changes in all three units, so that by August 1978 the NPS could release a draft general management plan (GMP) for public review and comment. By the end of that year planners nearly completed the GMP, something which served as the basis for NPS efforts to continue land acquisition, manage park resources, and provide visitor services.

Establishing a presence

Until January 1975, Klamath Falls Group Superintendent Ernest Borgman coordinated most of the activities related to the monument's establishment from his office in Klamath Falls. [2] The transition to on-site administration began in October 1974, when Borgman asked the chief ranger at Lava Beds National Monument, Ben Ladd, to go to John Day on a periodic basis. [3] Despite having been at Lava Beds for just over a year at the time, Ladd made almost weekly trips to eastern Oregon for the next two months. He moved to John Day early in 1975 on a formal detail whose purpose centered on the coordination of establishment efforts and the maintenance of public relations. [4]

Locating office space posed an initial problem, but Ladd soon accepted an offer to use facilities in the Malheur National Forest Supervisor's Office in John Day on a temporary basis. This gave him time to work with the General Services Administration to secure a permanent headquarters for the prospective national monument. Despite some questions from local residents about relatively long driving distances to the monument's three units, Ladd moved to a leased office near downtown John Day in mid-December 1975. [5] He and other NPS officials reasoned that a headquarters in John Day provided the agency with visibility unattainable elsewhere in Grant and Wheeler counties, while allowing future park staff to secure housing. [6]

Contacts with local landowners during the period between authorization and establishment consisted largely of informing them about change associated with administration of a national monument. As part of this public relations effort, Ladd and several other NPS employees gave talks and slide programs to service clubs and other groups in John Day, Fossil, and Condon during the summer of 1975. [7] The education efforts extended to hunters and fossil collectors once the NPS assumed control of state park lands on July 1, 1975.

Ladd then hired two seasonal employees, Daron Dierks and Bob Johnson, largely to do maintenance on facilities inherited from the state. These consisted of eight toilets, eight picnic tables, and eight garbage cans. [8] Dierks and Johnson split the duties associated with these facilities, but also made a number of signs and information boards to assist visitors. Since the park had no maintenance facilities for producing these signs, the seasonals accomplished the work at ../home. [9]

|

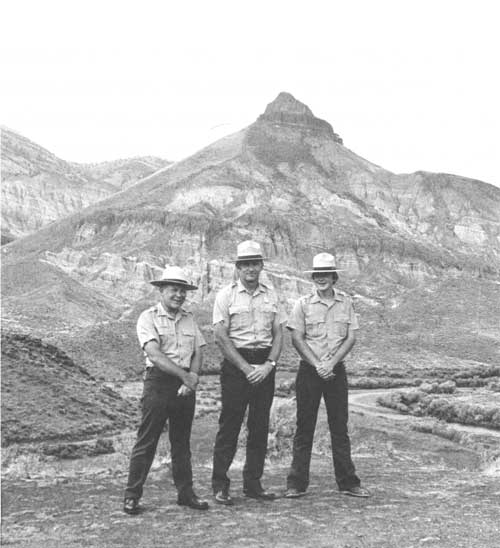

| Park staff in 1975. Left to right are Daron Dierks, Ben Ladd, and Bob Johnson. (NPS photo) |

In addition to their maintenance duties, Dierks and Johnson joined with Ladd in a public relations effort to stop hunting and fossil collecting on NPS lands within the authorized monument. They concentrated on stopping collecting in Blue Basin and ending the use of Painted Hills as a base camp for hunters. [10] As a result of these efforts, Ladd considered unauthorized fossil collecting to have become negligible by the following year. [11] Unauthorized fossil collecting virtually ceased by the end of 1978, though enough problems with vandalism and hunters occurred to warrant having three people with law enforcement commissions on the staff. [12]

Protection did not constitute the sole reason for increasing the number of NPS employees. They numbered eight permanents by the end of 1978, though some had less than full-time appointments. Staffing began once Ladd officially became superintendent on September 28, 1975. [13] Although Borgman helped him fill a staff assistant position two months later, that individual, Francis Kocis, did not enter on duty until January 1976. [14] After obtaining some clerical help early in 1976, Borgman assisted Ladd in establishing a permanent park technician position and more seasonal positions in maintenance, protection, and interpretation. [15]

Ladd did not fill the park technician position until he could make it a GS-9 interpretive park ranger, which happened in 1978. [16] By the end of 1977 two permanent maintenance positions had been established, in addition to a permanent less-than- full-time park technician who served as area manager for the Painted Hills and Clarno units. Ladd stationed the latter employee at Fossil, where protection and public relations efforts could be maintained from a small office in the county courthouse. [17]

From the outset, Ladd cultivated a number of working relationships with state and federal agencies. Interagency assistance and cooperative agreements were essential for a monument with noncontiguous units, especially when attempting to deploy a small staff to protect resources and inform visitors about the park. This led him to begin making contacts in 1975 at all three levels of government so as to lay the groundwork for future operations.

Since the NPS initially had no fire protection capabilities at any of the monument's three units, Ladd worked with the Oregon Department of Forestry to have a cooperative agreement in place by 1976. [18] Signage agreements with the Oregon State Highway Department (OSHD) took longer because the NPS had to deal with three different OSHD districts. This necessitated Borgman's assistance, and by the middle of 1976 the NPS received permission to place signs on the right- of-way within the Sheep Rock Unit. [19] During the following year state highway officials agreed to place directional signs on the right-of-way in all three units of the monument. [20]

Coordination with two Bureau of Land Management districts resulted in the issuance of special use permits for grazing on parcels in the Sheep Rock and Clarno units where the NPS previously agreed to allow this activity. [21] Without positive boundary identification, however, grazing could not be controlled on lands transferred from the state. Accordingly, Ladd made survey of the monument boundaries one of his main objectives so that fencing of lands in federal ownership could follow. [22] The NPS let a contract for survey of the Painted Hills Unit in 1976 and scheduled work to begin in the Sheep Rock Unit in early 1978. [23]

Ladd's other main objective centered on having something to show visitors. Interpretive planning at first emphasized visitor orientation at the headquarters in John Day along with placement of temporary wayside exhibits in all three units. [24] Other than a park brochure written under contract in 1976, little in the way of formalized interpretive services took place until the following year. [25] At that point Ladd reported that exhibits had been placed in the John Day office. These devices served over 4,800 visitors who stopped for information over the course of 1977. [26] In the field, seasonal interpreters began supplementing their periodic programs for community groups and schools with evening campfire talks that summer at the newly established Clyde Holliday State Park near Mount Vernon. [27] By far the most important event, however, occurred in May 1977 when the Cant Ranch visitor contact station opened.

In addition to being a place to which visitors could come seven days a week that summer, the ranch house also provided indoor display space. This allowed the NPS to justify its first significant museum acquisition, a fossil nut and seed collection it purchased in July 1977. [28] With this on display at the Cant Ranch, Superintendent Ladd could show visitors a tangible part of the fossil resource within the monument's boundaries.

The opening of the ranch house also signaled a shift away from headquarters as the place where the NPS made most of its visitor contacts. This came faster and in greater volume than planners originally anticipated, and stymied their efforts which previously focused on providing a means to interpret the upper John Day Basin from headquarters and at waysides. [29] By the end of 1977, Ladd cited "an ever increasing interpretive need" when he proposed to convert the monument's staff assistant position to that of an interpreter. [30]

Acquisition and rehabilitation of the

Cant Ranch

Borgman's efforts to obtain buildings and a portion of the Cant Ranch came to fruition in January 1976 after more than two years of negotiations. This 878 acre acquisition served to greatly consolidate NPS holdings in the Sheep Rock Unit, but came with a stipulation that the Cant heirs had seven years continued use of all property except the ranch house. As a centerpiece in the park, this ranch house immediately became a focal point for visitor contact and administration. It also served as the venue for a dedication ceremony in August 1978 that consummated many months of rehabilitation work on the building.

|

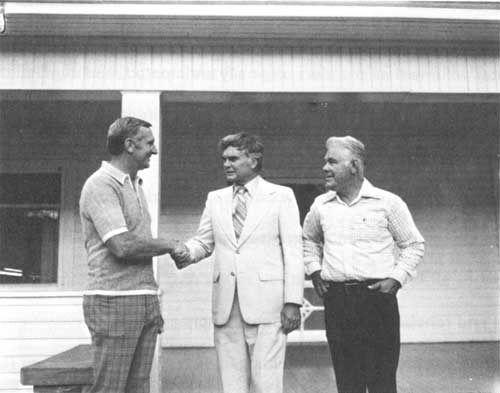

| Ben Ladd, Al Ullman, and Ernest Borgman at the Cant Ranch, August 1977. (NPS photo by Daron Dierks) |

Although Congressman Al Ullman did not include provisions concerning sale of the Cant Ranch into the monument's authorization, the NPS strove to make good on what Borgman promised in 1973. Since the legislation confined negotiations to 878 acres within the monument's authorized boundaries, this precluded NPS consideration of the entire 5,925 acre ranch that James Cant, Jr. previously indicated a desire to sell. [31] Much of the property inside Sheep Rock Unit boundaries consisted of bottomland (which made the remaining acreage viable for ranching), so one of the terms of sale stipulated that Cant could have continued use of his property--except the ranch house and associated outbuildings--for seven years. Cant also retained a 40 acre homesite that abutted the state highway one half mile south of the ranch house, thereby reducing what the NPS acquired in January 1976 to just over 849 acres. [32] Implementation of Borgman's commitment to use oral history in developing the interpretive theme of ranching in north central Oregon began with taping interviews with local residents in the summer of 1976. [33] To reinforce this theme, Ladd agreed to furnish two rooms in the ranch house with some of the Cant family's furniture. [34]

|

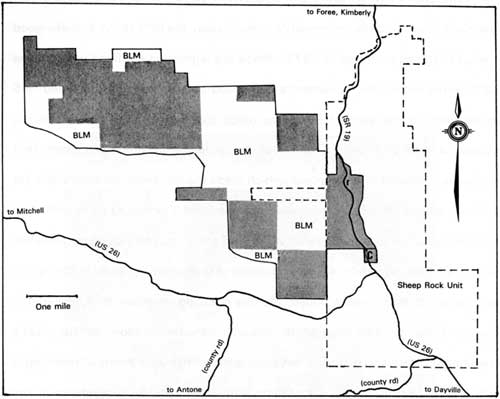

| Extent of the Cant Ranch in 1975. Shaded parcels are part of the 5,925 acres owned outright by the Cants, though tracts marked "BLM" are areas under lease. Dotted lines indicate the authorized boundary of the Sheep Rock Unit which surrounded the 878 acres that the NPS bought in 1976. The "r" indicates the approximate location of the main house, while "C" denotes the homesite retained by John Cant, Jr. |

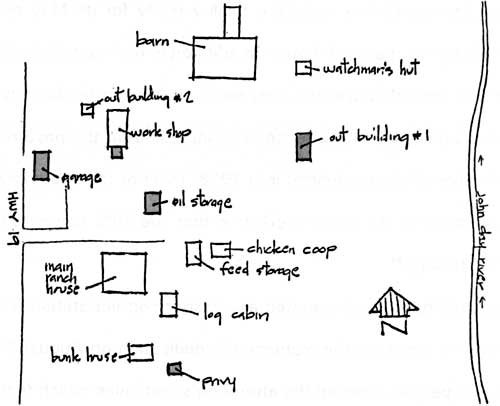

A survey of the ranch house and associated outbuildings during January and February of 1976 constituted the first step in rehabilitating the property as a visitor contact station. [35] Denver Service Center personnel then generated a report for the List of Classified Structures (LCS), an evaluated inventory of all structures that possess archeological, historical, and/or architectural significance in which the NPS has or plans to acquire legal interest. [36] In this instance, the LCS report served as a starting point for programming the cost of contracts associated with rehabilitation. Beginning in early 1977, contractors eventually insulated the ranch house, reroofed the barn, provided a sewer line, paved the parking lot, and installed a new water system. [37] In addition, the report found that five outbuildings did not contribute to the historic integrity of the ranch and could thus be removed. [38]

|

| Sketch map of buildings at the Cant Ranch, February 1976. The five structures recommended for removal are shown by shading, and, except for the privy, were demolished later that year. |

Most initial work on the ranch house grounds consisted of a general cleanup while the monument staff awaited approval of rehabilitation plans. [39] While the initial work took place, the ranch house and grounds remained open only as a restroom stop for the public. [40] This situation lasted for some 15 months, as Ladd aimed to open the ranch house and grounds for public use by May 1977. [41]

While contractors began installing water and sewer systems in early 1977, NPS crews also worked to make the facility ready for its May opening. They rewired and reroofed the ranch house, in addition to making substantial changes to its interior that extended over the summer. [42] By August the lawn had a sprinkler system, new sidewalks, and a fence separating it from the pasture. [43] Although the rehabilitation project extended into 1978, most of the later work centered on outbuildings such as the ranch workshop that the NPS converted into a small maintenance facility. [44]

The ranch house had operated as a visitor contact station for more than a year by the time it hosted the monument's dedication on August 23, 1978. An estimated 950 people attended the afternoon's festivities which featured remarks from NPS officials and some of the principals instrumental in the campaign for establishing a national monument. [45] Speakers included NPS Director William Whalen, Ernest Borgman, Ben Ladd, David Talbot, Jack Steiwer, circuit court judge J.J. Murchison, rancher William Cant Mascall, and Congressman Al Ullman, who gave the keynote address. [46] Not only did the dedication serve as a way to formally open the monument for future public use, but it also provided an opportunity for the NPS to release its draft general management plan for public comment. [47] This event thereby served to honor the efforts which resulted in the monument's establishment, but also appeared to be a significant juncture in park planning.

|

| West facade of the main ranch house as seen from State Highway 19 in January 1976. The second floor sun porch was removed as part of the subsequent adaptive rehabilitation. (NPS photo by A. Donald) |

A prototype planning process

Since the master plan formulated prior to the monument's establishment remained unapproved, a NPS planning team met in John Day over a one week period in November 1975. As directed, they diverged from what had been the master plan process and aimed at generating a document supported by contracted studies as well as subsidiary plans. Although Ladd subsequently saw the monument's GMP as too narrow in scope because managers and staff did not know enough about park resources, supporting material served as guideposts while NPS infrastructure developed in the upper John Day Basin. [48]

In reopening the monument's planning process, NPS officials sought to make a transition from master plans (which tended to emphasize development of park facilities over resource management concerns) to a more even-handed process. The need to comply with requirements in the National Environmental Policy Act and other legislation brought about environmental statements to accompany master plans in the early 1970s, but the NPS planning process still lacked meaningful public participation. This led to a NPS task force in 1974, which recommended that master plans be replaced with general management plans. By emphasizing resources and visitors (while relegating development to a role of implementing management decisions reached after public review), the GMP represented an improved means of resolving issues and reaching objectives, while affording the public a greater opportunity for input. [49]

The team which initiated the new planning process in John Day during November 1975 began by drafting a statement for management and an outline of planning requirements. They intended to identify issues, problems, and objectives in the former, while the latter represented a first attempt at scheduling needed documents. [50] In preparing for the next step, which focused on generating alternatives for resource management and visitor use, the team found a need for additional baseline information. Paleontological inventory topped their list, since there had been virtually no scientific input to the planning process since J. Arnold Shotwell's assessment of the entire upper basin during the feasibility study of 1967. [51]

After their November meeting, the planning team prevailed upon the NPS regional office in Seattle to request proposals for basic paleontological information. [52] They accepted a proposal from John Rensberger of the University of Washington and let a corresponding contract. Completed in just over a month, Rensberger divided his report into sections on paleontologic resources located in and near the monument, protection, interpretive themes, management alternatives for paleontologic research, and site development. [53]

Rensberger introduced his section on paleontologic resources by defining them, and then proceeded to assess monument lands with respect to how they represented vertebrate and plant fossil localities in the Clarno, John Day, Mascall, and Rattlesnake formations. [54] Perhaps more importantly, he dropped a bombshell on the NPS with a finding that the Clarno Unit as authorized did not appear to contain any important paleontologic resources. As Rensberger went on to explain, fossil localities associated with the Clarno and John Day formations are located a short distance north of where planners had drawn the unit's boundary. [55] In the Painted Hills Unit, Rensberger found two members (of four) known to comprise the John Day Formation. [56] He emphasized that important assemblages of fossil vertebrates occurred in these same two members within the Sheep Rock Unit, as did paleontologic resources associated with the Mascall and Rattlesnake formations. [57]

To put these findings in perspective for the planning team, Rensberger prefaced them by stating that no geographic locality in Oregon contains a complete stratigraphic section. [58] He placed emphasis on the John Day Formation as having the best examples of evolutionary transitions in situ of any terrestrial fossil deposit in the world, while also estimating that it contained 95 percent of the region's known paleontologic resources. [59] With that in mind, Rensberger found the monument to contain only about the older one-third of the chronology present in the fossiliferous John Day Formation, though adjacent localities have roughly another third of the fossil-bearing sequences. [60]

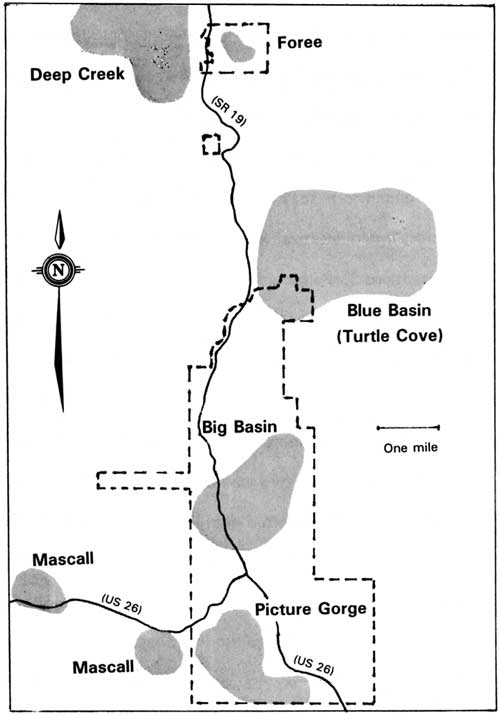

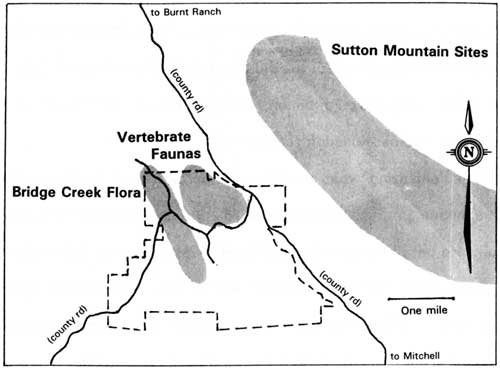

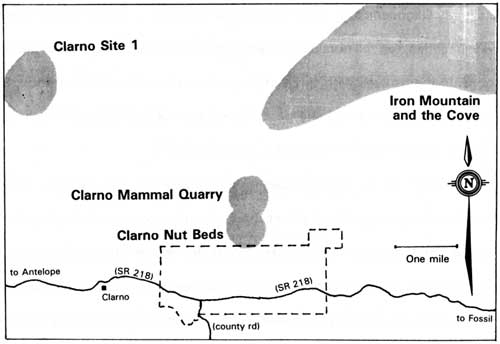

|

| Generalized map of paleontological resources in the vicinity of the Sheep Rock Unit, Painted Hills and Clarno derived from Rensberger's report. Fossil localities are indicated by shading. (in USDI-NPS, Park Resource Maps, August 1976) |

After summarizing what constituted important fossil localities within and around the monument, Rensberger ranked 16 areas under four levels of priority for protection. He based them on the likelihood of resource loss without protection and the magnitude of that loss if it occurs. First priority in this scheme represented those localities which Rensberger judged to potentially contain the greatest amount of important, but unknown, paleontologic information. As might be expected given his survey findings in the first section, he emphasized protection of the Clarno and John Day formations because they contain the best preserved faunas of these age intervals (early Oligocene and Oligo-Miocene) on the west coast of North America. Of the 16 localities, ten fell outside monument boundaries. Although NPS planners could console themselves with three of the top four localities (Sheep Rock, Blue Basin, and Foree) being inside the park, Rensberger underlined the necessity of acquiring the Clarno Mammal Quarry by listing it first. [61]

As for measures to protect paleontologic resources, Rensberger began by stating that cattle grazing did not affect the rock exposures containing fossils. He cautioned against creation of large reservoirs for water storage because the increased humidity might extend vegetation to cover bare slopes, thus eventually burying fossils of the John Day Formation in soil. [62] In describing threats posed by public access, Rensberger thought the proximity of roads at Blue Basin and Foree might tempt visitors to try unauthorized collecting, though walking over the Big Basin Member of the John Day Formation could be equally as damaging to fossil resources. [63] He recommended limiting access to roads other than highways within the monument and locating trails away from fossil exposures. His report also identified localities which could be effectively patrolled from the highway or by foot, and discussed how to prevent impairment of fossil resources from the effects of weathering. The latter, he emphasized, had to be done proactively through professional collectors in conjunction with a carefully planned research design because valuable data could otherwise be lost. [64]

For much of the last half of his report, Rensberger formulated interpretive themes for each unit and tied them to relevant literature. He also reinforced his recommendations about protection by emphasizing how an active research program could provide interpretive data. Rensberger's concluding section on development weighed considerations about protection and interpretation in recommending where to site a visitor center. After reviewing a number of locations in the Sheep Rock and Painted Hills units, he saw Foree and Blue Basin as best suited for such a facility. [65]

Due to time constraints, Rensberger's paleontological information and recommendations served as virtually the only supporting material to the planning team's effort to further develop a statement for management. They drafted an introductory section in November 1975, but now had to articulate issues, problems, and objectives in more depth. To do this, they divided the introductory section into six parts: park purpose, significance of the monument's resources, land classification, influences on management, research needs, and management objectives. [66]

Since the authorizing legislation approved by Congress came without a statement of the park's purpose, planners had to generate one from the monument's legislative history and unapproved master plan drafts. All five bills referred to congressional committees from 1969 to 1973 included a sentence which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to establish the monument "to preserve and protect for the education, inspiration, and enjoyment of present and future generations a great number of flora and fauna fossils constituting a unique geological formation." [67] The Department of the Interior's report in 1973 drew from these bills when it stated that the monument is intended to "preserve, protect, and interpret the extensive tertiary fossils found in the geological formations of these areas." [68] The reference to "these areas" meant those lands within the boundaries of the three state parks and "other such areas as the Secretary [of the Interior] determines to be suitable for administration as part of the monument." [69]

Actual wording of the park's purpose evolved from statements in unapproved master plan drafts, beginning in January 1971:

"The primary purpose of this [park] proposal is to acknowledge, identify, interpret, and protect the paleontological and geological resources existing in this region. A secondary purpose is to provide public facilities which will promote and facilitate a concept of visitor use." [70]

By August 1971, this directive had been revised to state:

"The primary purpose of this proposal is to identify, interpret, and protect the geologic and paleontological resources of the Upper John Day Basin. A secondary purpose is to provide those public facilities that will provide and assist visitor use of the monument." [71]

This statement remained unchanged in the master plan drafts of June 1972 and April 1973. Wording that appeared in the statement for management in June 1976 reflected an emphasis in the new planning process on resource management and visitors:

"To identify, interpret, and protect the geologic, paleontological, natural, and cultural resources along the central and upper John Day River and to provide facilities that will promote and assist visitor recreational enjoyment and understanding of the same." [72]

According to the 1974 authorizing legislation, the NPS shall administer the monument consistent with its Organic Act of August 25, 1916, as supplemented and amended. The latter provides authority to manage the monument's natural and cultural resources, but is also a mandate to promote and regulate visitor use. Justification can be made for the investigation, study, and monitoring of resources which exhibit qualities of national significance on non-NPS lands, but interpretation and protection of resources located outside the monument's authorized boundaries is clouded by legal uncertainties. [73]

Even though planners derived three maps showing paleontological resources identified in Rensberger's report, their statement of significance in the introductory section to the Statement for Management (SFM) focused on testimonials and generalities about the upper basin. [74] They made fewer allusions to the monument's fossil resources in components of the SFM which centered on land classification, influences on management, and research needs. In the management objectives, however, planners listed preservation and study of the monument's plant and animal fossils first, though this did not necessarily imply priority over other objectives. [75]

The second part of the monument's SFM expanded on the management objectives by utilizing an environmental assessment format to present two general management alternatives for resources management and three options concerning visitor use. [76] With them, NPS officials hoped to elicit public views on issues and alternatives so that a draft general management plan could be formulated. Ladd reported that park staff contacted all interested groups in the local area on an informal basis prior to the public workshop held on the SFM and alternatives at Spray in July 1976. [77] Although the workshop greatly augmented completion of the SFM's introductory section, finalization of resource management and visitor use plans to support management objectives became dependent, to varying degrees, on research. [78]

A need for studies or surveys about different resource types became evident early in the planning process. Establishment of a cooperative park studies unit (CPSU) at Oregon State University (OSU) in 1974 greatly facilitated progress on research needs identified as common in both resource management alternatives because contracted studies could now be funneled largely through one entity. [79] The first project for John Day Fossil Beds aimed at producing an inventory of natural resources to support the SFM and associated alternatives. It appeared as a series of resource maps in August 1976 after the Denver Service Center provided printing and graphics services. [80] Concern about obtaining a starting point for comparisons between grazed and ungrazed areas, especially where this could impact threatened and endangered species, led to a plant inventory conducted during 1976. It identified 230 species, of which the investigators considered eight to be rare or threatened. [81] Another CPSU study combined what the SFM and alternatives identified as a need to study mule deer and coyotes in the Sheep Rock Unit. [82] Since the CPSU largely focused on natural resources, the NPS contracted separately for an archeological survey. It went to an investigator at OSU who completed his report on the monument's historic and prehistoric resources in 1977. [83]

NPS officials employed a combination of research and interpretive planning to support visitor use alternatives. They contracted with the CPSU to obtain management recommendations about potential visitor impact on nesting raptors. [84] The U.S. Geological Survey study of water supplies and flood hazards, however, had a greater impact on decisions concerning development. It pointed to the danger of cloudburst flooding at Clarno, thereby eliminating any consideration of camping at Indian Canyon in favor of a day-use picnic area. [85] A separate interpretive plan appeared in March 1978. It provided guidelines for design and content of a visitor center, interpretation at the Cant Ranch, and the location of wayside exhibits. Other components of the plan included a scope of collections statement, along with a short pronouncement about the creation of a park library as well as one concerning the encouragement of research to aid interpretation. [86]

Supported by an interpretive plan and most of the contracted studies, the draft GMP released for public review at the monument's dedication largely followed a format established by the SFM and associated alternatives in 1976. Now divided into four parts (statement for management, resource management, visitor use, and general development),the GMP corresponded to procedures delineated in the newly issued NPS Planning Process Guideline, also referred to as NPS-2. [87] This document formalized and prescribed what had been prototype planning at parks such as John Day Fossil Beds and directed that the plan's public review period be at least 30 days prior to approval by the regional director. [88]

The NPS received seven written comments on its draft GMP. Development of visitor facilities, especially those at Painted Hills, constituted the most popular subject. [89] Approval for the monument's GMP finally came in July 1979, largely because of changes in format and some rewrites in all four sections. [90] Some additional revision in the resource management section delayed the appearance of a final GMP until October 1979. [91]

Legislated boundary changes

Within four months of the monument's establishment, NPS officials recognized problems in all three units which necessitated adjustments in authorized boundaries. They took care to avoid accusations of unwarranted expansion by limiting the monument's size to no more than the already authorized 14,402 acres. [92] Rensberger's report became the tool to pursue boundary changes aimed at incorporating significant paleontological resources lying adjacent to the monument as early as January 1976. [93] Planners stipulated, however, that additions had to be compensated by deletions of land next to park boundaries which did not contain fossils, and had instead a higher use for game management or public hunting. [94] This made changes in the Clarno Unit's configuration the driving force behind this legislation because they represented paleontological resources not otherwise represented within the monument. [95]

At first, the proposed additions at Clarno consisted of only 360 acres because NPS planners rigidly followed what the CPSU resource map derived from Rensberger's findings indicated as the location of the nut beds and mammal quarry. [96] Consequently, Congressman UlIman drafted a bill introduced in the House of Representatives on July 15, 1977. It referred to a map containing this change and one deleting 545 acres of private land at Clarno, in addition to 80 acres of NPS property identified for use as trading stock. [97] UlIman visited the monument on August 8, 1977, at which time Ladd and Camp Hancock director Joseph Jones approached him with a proposal to add another 560 acres to the Clarno Unit. [98] Jones supplied sufficient detail concerning significant paleontological and archeological sites located there for UlIman to request an official NPS position on the proposal. [99] Once the NPS supplied a statement of significance, information about land ownership, and cost estimates for acquisition, UlIman incorporated both additions into his bill. [100]

|

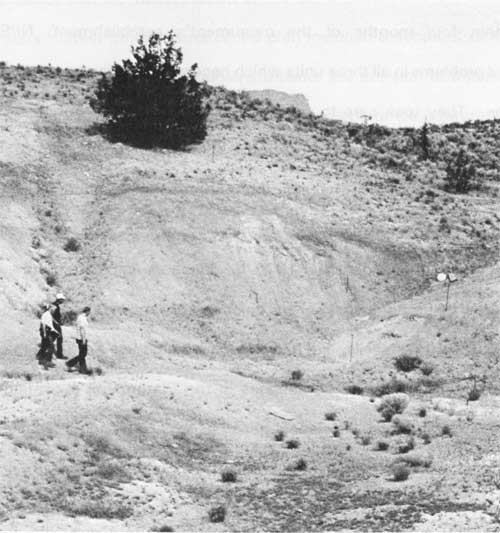

| View of the mammal quarry in July 1977. At the time it was located outside of the Clarno Unit's authorized boundary. (NPS photo) |

Boundary adjustments at Painted Hills stemmed from landowners proposing to construct a dam which could back reservoir water into the unit. Borgman and Ladd opposed the project at a meeting with the Soil Conservation Service and local ranchers in 1975, but it surfaced again when Brooks Resources Corporation bought several key parcels in the spring of 1977. [101] Several months later they secured an impoundment permit from the State Division of Lands for a dam site located less than one-quarter mile north of the Painted Hills Unit. The new owners began construction of the dam by mid-1978, and shortly thereafter proposed to extend the dam 27 feet higher than authorized. [102]

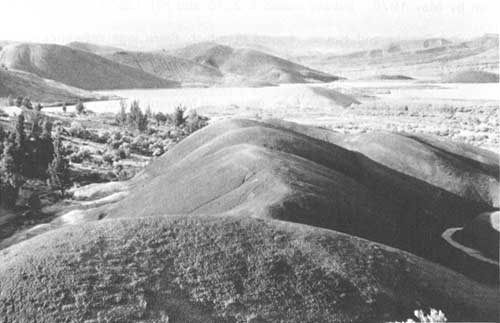

|

| Water impoundment as seen from the Painted Cove Trail, Painted Hills Unit, 1992. The inundation shown has yet to reach levels authorized by the land exchange with Brooks Resources. (photo by the author) |

This latest proposal came relatively late with respect to adjusting monument boundaries in legislation, but it represented an opportunity for the NPS to have virtually all of the Painted Hills Unit in federal ownership. In exchange for allowing 50 acres of federal land to be inundated, Brooks Resources agreed to sell 300 acres located within the authorized boundaries on either a fee or less-than-fee basis. Since the 50 acre parcel did not possess any known paleontological resources, the NPS agreed to terms which included removal of a stock driveway along the road through Painted Hills. [103] The revised legislative proposal also allowed acquisition of a 40 acre parcel owned by the state which had previously been excluded. [104]

The 849 acre acquisition at the Cant Ranch in January 1976 pointed to lift the authorizing legislation's 1,000 acre limitation in obtaining fee title to privately- held land. Furthermore, the 1974 act provided only $400,000 for acquiring such interest, and the NPS spent nearly all of this amount on the Cant Ranch. [105] To remedy this, the NPS Lands Division recommended that another $3.5 million be authorized for buying property within the monument's boundaries. [106] They earmarked much of it for acquisitions in the Sheep Rock Unit because several property owners there indicated a willingness to negotiate the sale or exchange of their land. [107]

In order for the NPS to justify the purchase of 2,500 acres in this unit, it had to recommend deletion of lands from the monument. Since Rensberger could find no paleontological resources in sections 16, 21, and 28 east of Picture Gorge, NPS officials had little difficulty agreeing to 1,280 acres of deletions but kept half of that total for exchange purposes. They could show a net decrease of 727 acres in the Sheep Rock Unit's authorized total, so a proposal to transfer 80 acres of BLM land at Foree met no resistance. [108]

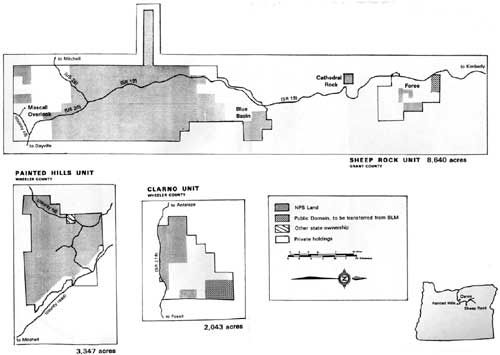

Overall, the NPS recommended decreasing the monument's authorized size by almost 372 acres. As expected, this proposal experienced no difficulty in Congress while UlIman's original bill eventually became part of larger omnibus legislation. Introduction of HR 9601 signaled the start of the legislative process in October 1977, something which led to testimony at a subcommittee hearing by a witness from the Department of the Interior on November 28. At that point the witness stated that the NPS still had to finish a corresponding map for changes at John Day Fossil Beds. [109] The delay did not prove to be an obstacle, as provision for the monument's boundary adjustments became part of amended omnibus legislation by May 1978. Initially called S 2876 and HR 12536, the bills had accompanying Senate and House reports in which there was reference to a completed map and an acquisition ceiling of $3.5 million. [110] A conference version, S791, carried identical wording, which, on November 10, 1978, became law as part of P.L. 95-625. [111] This reduced the monument to 14,030.51 acres, but Ladd and other NPS officials described the new boundaries as providing better protection of fossil resources. [112]

|

| Monument boundaries authorizing a total of 14,030 acres resulted from passage of legislation in 1978. The NPS partially offset deletion of acreage totaling two sections (1,280) acres in the Sheep Rock Unit with an increase at Foree, but the park total declined even with an expansion at Clarno and a slight gain at Painted Hills. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002