|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Three:

CAMPAIGN FOR A NATIONAL MONUMENT

Backed by a powerful congressman, supporters of national monument status for the John Day Fossil Beds obtained its establishment in 1975. Four of them secured Representative Al Ullman's interest in 1967, and persevered to increase the statewide appeal of their proposal. They met little local opposition in doing so, even though acreage in the proposed monument eventually doubled in size over what it had been in 1969.

Despite the unquestioned national significance of the proposed monument's paleontological resources, "feasibility factors" delayed congressional authorization of the park. One stemmed from mutual distrust between the state and National Park Service Director George Hartzog, something which resulted from a failed attempt to establish the Oregon Dunes National Seashore in 1966. Another involved coordination between the federal and state governments, because implementation of Ullman's legislation depended on planning done by the NPS through its regional, state, and group offices. Once the groundwork for land acquisition and development of visitor facilities fell into place, however, members of Oregon's congressional delegation brought about authorization of the monument by assisting passage of an omnibus bill.

Background to the park

proposal

Establishing a national monument differs considerably from the administrative procedure used to create additions to Oregon's state park system. Like other types of federal reservations, national monuments are generally subject to the legislative process. National significance and strong political support are requirements for establishing monuments, as are cordial intergovernmental relations when land transfers are needed for sites in state park status.

Although John C. Merriam frequently touted the upper John Day Basin as a "mecca" for visitors interested in appreciating change through geologic time, he maintained that the area did not "fully reach the status of a National Park or National Monument." [1] This is despite Merriam continually promoting the area as having qualities which appeared to satisfy national park standards he formulated while serving as chair of the National Park Service's Committee on the Study of Educational Problems. [2] Doubts about the NPS, rather than any concerning the John Day reservation's significance, made him take this position. In 1943, when Merriam described the importance of a close relationship between his parkway proposal and activities of the Committee on Educational Problems in Oregon Parks (CEPOP), he stated that the NPS concerned itself more with technical problems of administration and protection instead of education and research. [3] Use and administration of the John Day reservations, in his view, should be driven by an educational focus--one which CEPOP could foster and direct in conjunction with the state parks organization. [4]

In any event, no statutory definition exists for the "national park" or "national monument" designations. The latter has been characterized as areas not sufficiently outstanding to justify national park status, yet possessing values which merit protection and control by the federal government. [5] National monuments in the United States have a great variety of scenic, geological, biological, archeological, and historical features--so much so that generalizations are difficult. As one writer put it,

"A national monument is a piece of land containing from one to one million acres, either flat or rough, timbered or bare... But the most clearly outs tan ding character of the national monument is its complete inconsistency. [6]

National monuments can be proclaimed by the President under authority granted by the Antiquities Act of 1906, or are legislated by Congress. Although many of the early monuments became part of the National Park System as the result of presidential proclamations, most of those established since 1950 have been through legislation. [7] ]When the legislative process is used to establish a monument (or any other unit of the National Park System, for that matter), it might seem obvious that support for the area must outweigh opposition or political inertia. For this to occur, however, the proposed area should demonstrate some degree of national significance while its proponents convince Congress to act through a sponsor, who is usually a member of the home state's congressional delegation. [8]

More than anything else, a failed attempt to establish a national seashore on the Oregon Coast hampered supporters of a national monument in the upper John Day Basin. Born from a 1959 NPS study, an "Oregon Dunes National Seashore" originally involved 32,000 acres--much of which had to be obtained from private owners and the U.S. Forest Service. [9] Once it evoked local opposition, Congressional supporters rewrote the authorizing legislation several times. By 1965 the seashore proposal had new boundaries, something which resulted from a report prepared by the NPS in 1963. [10] Several state parks became part of the new proposal, which Oregon congressman Robert Duncan introduced as HR 7524 in 1966. [11] Despite the bill passing the House, it died on the Senate calendar because one of Oregon's senators, Wayne Morse, threatened to stymie debate with a filibuster. [12] Consequently, the Department of the Interior dropped this proposal from its legislative requests because the Oregon delegation collectively failed to support it. [13)]

The Oregon Dunes episode might have had little relevance to a park campaign in the upper John Day Basin had there not been a controversy over whether state parks could be transferred to the NPS. According to state parks superintendent David G. Talbot, the seashore proposal failed in Congress once the state demanded compensation for its land. [14] This position reportedly infuriated NPS director George Hartzog, but the state maintained that it had not been thoroughly informed about the bill's provisions. [15] As a result, the NPS believed the state to have no interest in transferring any of its parks. [16] An opinion dated October 14, 1966, by Oregon's attorney general reinforced this perception. It advised that without additional authority from the state legislature, the highway commission possessed no authority to convey these parks unless they could be declared surplus and no longer needed for public use. [17]

Congressman Al Ullman stayed out of the Dunes controversy, but he asked the NPS to study several areas in eastern Oregon for their feasibility as National Park System units after assuming his congressional seat in 1957. [18] While the state and Hudspeth experienced difficulties over their co-ownership of Painted Hills State Park, J.P. Steiwer contacted Ullman about that area's potential as a national monument. Ullman took this request seriously because of Steiwer's status as mayor of Fossil and his having served as a state representative. The request stemmed from Steiwer having visited Craters of the Moon National Monument in the 1950s, while on his way to Yellowstone National Park. Since the scenic and geological features at Craters of the Moon encourage travelers to stopover on their way to a major destination such as Yellowstone, he reasoned that Painted Hills lay in a somewhat analogous position. [19]

Ullman wrote to Hartzog in June 1965, requesting an informal evaluation of Painted Hills or a combination of related sites for administration by the NPS as a national monument. [20] The letter went to the agency's Western Regional Office in San Francisco, which in turn referred it to a field office located in Portland. Despite an acknowledgment that a field investigation should be made before commenting, Dan Burroughs of the Portland office submitted an evaluation based on secondary source material to the regional director in October. [21] Burroughs concluded that a thirteen acre park did not warrant national monument status in itself, but emphasized that other localities in the upper John Day Basin possessed outstanding scenic and scientific importance. He thereby recommended an intensive field examination be conducted before making any definite conclusions about a national monument. [22]

The field examination, however, had to be deferred for at least one year while NPS study teams met commitments elsewhere. [23] In the mean time, University of Oregon paleontologist J. Arnold Shotwell made the NPS regional office aware of the Sheep Rock area's eligibility as a National Natural Landmark. Regional archeologist Paul J.F. Schumacher evaluated a 2,000 acre area, mostly located within Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park, based on a brief field investigation made in 1963. [24] Schumacher recommended the site for designation, as did the Secretary of the Interior's Advisory Board, so that formal application could follow from Governor Mark Hatfield on June 15, 1966. [25] Once the NPS conveyed landmark status six days later, it established that at least part of the upper basin possessed national significance. [26]

If nothing else, the landmark designation served to encourage supporters of a national monument in Grant County. Interest there had been expressed several years earlier by county parks commissioner C.L. "Buck" Smith, a friend of Ullman's. Smith, who owned an automobile dealership in John Day, experienced little difficulty in getting his daughter Lura and son-in-law Gordon Glass involved with a national monument proposal. [27] Glass hired a photographer to take pictures of the Sheep Rock area as early as 1963, but his first official connection with this proposal came once Grant County organized a planning commission in 1965. [28]

Under the leadership of county agent Bill Farrell, this commission undertook studies of Grant County's economic potential. [29] As a member of the commission's recreation committee, Glass wanted to better quantify the economic potential of tourism. This might make the benefits of national monument designation, as one part of a strategy for the upper basin, more apparent. Glass subsequently wrote the historical and geological sections of a report on Grant County's recreation potential in 1966. [30]

After Ullman obtained the Grant County report in early 1967, he compared a potential national monument in the upper John Day Basin with Nez Perce National Historical Park in Idaho. [31] This stemmed from one of the report's recommendations which called for core areas to be preserved in a national monument, in concert with wayside geological markers over the wider area to tie the park concept together. [32] Ullman continued to have the backing of Wheeler County officials to pursue an evaluation of the upper basin, so he requested the NPS to supply a study team on April 7, 1967. [33]

Prelude to a master plan

When a NPS study team visited Grant and Wheeler counties in June 1967, it found a series or combination of sites suitable for a national monument. Confusion over whether the state wanted to relinquish control of three state parks, however, led to a finding that inclusion within the National Park System did not appear feasible. Although the state offered cautious support for the proposal and its local backers succeeded in obtaining a number of endorsements throughout Oregon, the NPS showed its reluctance to do anything further about the proposition. A frustrated Ullman introduced legislation in February 1969, something which led to a commitment by the NPS to produce a master plan for the proposed national monument.

Formal announcement of the evaluation study came less than a week after Ullman's request. [34] This initially caught state parks officials by surprise, but Talbot pledged cooperation and assistance, if needed, in a carefully worded letter to Ullman. [35] In it, he acknowledged that Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park received only minor improvements in the past, but a "visitor interpretive center" would probably be considered for the 1969-71 budget. Formal interpretation of Painted Hills State Park, however, would have to wait until the culmination of negotiations to buy the more than 2,800 acres under easement. Talbot qualified his statement about Oregonians being reluctant to transfer their state parks to some other agency by indicating that the state needed time to formulate a position should the area meet NPS standards for national monuments.

Ullman forwarded the letter to the NPS, which responded through regional director John Rutter on May 24, 1967. Rutter defined the study's purpose as evaluating "the natural, scientific, and recreational resources of the area and to recommend possible courses of planning action that would appear to be in the best public interest." [36] Consequently, the NPS study team stuck to generalities and did not discuss actual boundaries of a proposed national monument.

The evaluation study consisted of two parts. Shotwell authored a report on the upper basin's paleontological significance, which firmly established its national importance and made suggestions for interpretation of these resources. [37] A separate report by other members of the study team concluded that scenic, historic, and recreation resources in the area possessed state or local importance. [38] The team did not make a determination about eligibility for national monument status during a two week field visit in June, something which concluded with Ullman holding public meetings about the proposal in John Day and Fossil. [39]

Before the study reached Washington, the NPS Office of Resource Planning in San Francisco acknowledged--upon corroboration by two other paleontologists--that the upper basin's major scientific sites warranted national monument status in accordance with Shotwell's conclusions. [40] Such status appeared to them, however, as conditional on the state's willingness to transfer Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds, Painted Hills, and Clarno state parks to the NPS. They construed Shotwell's suggestions for interpretation as implying the impracticality of establishing a national monument on lands outside of the three state parks. [41] The acting chief of Resource Planning then related how the study team's captain, Dan Burroughs, had seen Talbot's letter to Ullman. This supposedly advised the congressman that the state opposed transfer of its parks in the fossil beds. He then summarized remarks made by deputy state parks superintendent Richard McCosh during the study team's field visit. McCosh reportedly said that the state opposed a transfer until such time as the federal government might give specific information on how much money would be spent for development, with a definite program in terms of time. [42]

This became the basis for conclusions made by the Division of New Area Studies in Washington once they received a memorandum from Rutter which agreed with Resource Planning's assessment about lands outside the state parks. [43] They went somewhat further in stating that the three state parks perhaps contained the core or heart of the paleontological resources, and that these resources "already are available for public use and benefit." [44] The Division of New Area Studies concluded that "it would not appear feasible or desirable to make changes in this present arrangement since the State does not wish to release its interest in the area at this time" but left a door open to additional study if the state sought national monument status. [45]

With these conclusions in hand, the NPS presented its study to the Secretary's Advisory Board in November. With the boundaries for any discussion having been set, the board repeated NPS findings in its recommendation to Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.46] The Secretary agreed with the board and conveyed his decision to Ullman in December. [47]

What Talbot later termed to be an "after you, Alphonse" situation (in that both parties appeared to drag their feet on the national monument proposal by being overly formal in their dealings with each other) began when NPS assistant director Theodor R. Swem wrote to Governor Tom McCall about the board's recommendation in January 1968.48] Talbot drafted a response for McCall, one which urged a correction be made to the statement "the state apparently does not wish to release its interest in the area" because no one had asked them to relinquish the state parks. [49] At this point Talbot outlined a procedure to approve transfer of the state parks.50] The first step required obtaining administrative clearance from the State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee at its meeting on March 14. This committee approved a draft resolution, one which requested the NPS to conduct additional studies in the John Day Basin, though Talbot tabled it until the evaluation conducted in 1967 came out in printed form. Once the study appeared, Talbot sent the resolution to the highway commission members whose approval followed in July. [51]

In August the NPS readied itself for another request from Ullman, though this came to Secretary Udall on October 1, 1968. [52] Udall responded by stating that the state's interest in seeing national monument status pursued further did not constitute, in the Advisory Board's words, "actively seeking national monument status." [53] Once the state clarified its position by endorsing national monument status on November 15, the Secretary's office assured Ullman that a NPS study could be programmed "as soon as other commitments will allow. " [54]

While the state clarified its position, Glass sought to implement another recommendation stemming from the Grant County Planning Commission's report on recreation potential. This involved placing interpretive signs and markers along roadsides at geological points of interest. Gordon Glass and others wanted a loop tour to start at Mount Vernon, traverse west to Picture Gorge, go north to Kimberly, then east to Long Creek, and back to Mount Vernon on US 395. [55]

This project may have had its origins during a weekend excursion taken by three CEPOP members in November 1946. They met Thomas P. Thayer of the U.S. Geological Survey in John Day for an all day tour of Grant County's fossil localities. [56] This developed further while Thayer periodically returned to the John Day Basin over the next two decades. [57] During this period Thayer met Glass, who he found willing to coordinate the planning and placement of interpretive plaques for a geological tour of Grant County. [58] As a first step, Thayer wrote most of a booklet on the upper basin's geology published through the U.S. Geological Survey in 1969. [59] He tied the stops in its road log to locations where Glass and Buck Smith could obtain approval for installation of the plaques. [60] Sponsorship by Grant County ensured that most of the waysides had been constructed by the time Thayer's booklet appeared. [61]

Steiwer, meanwhile, continued to express Wheeler County's concern about the lack of visitor facilities in the three state parks and looked for ways to promote the proposed national monument. [62] As a board member of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS), Steiwer had access to an organization with statewide influence, something that could prove useful in lobbying the Oregon Legislature. [63] At the request of OHS director Thomas Vaughn, Steiwer presented the proposal at a board meeting on February 14, 1969. [64] Once he stressed the upper John Day Basin's paleontological significance and a need for better protection of its fossil resources, the board endorsed the proposal and expressed a willingness to help secure the legislature's backing for national monument status. [65]

Any action that the legislature might take, however, had to be deferred until the NPS prepared a master plan which better delineated the form for a national monument. In March, three state senators and one representative sponsored a memorial to the President and Congress for establishment of a 10,000 acre monument in Grant and Wheeler counties. [66] The state senate's Fish and Game Committee tabled the memorial after Burroughs advised them in his testimony that a master plan could supply precise acreage and specific development plans. When Burroughs reiterated a NPS position that no possibility existed for a master plan being prepared in 1969, this effectively precluded any action the biennial legislature could take until its 1971 session. [67]

Ullman gave the administrative approach one more try before introducing legislation in Congress. When writing to Hartzog in January, Ullman related that the state now sought national monument status and asked for further studies by the NPS. [68] After waiting four weeks without a reply, Ullman introduced HR 7625 on February 25, 1969. His bill authorized acquisition of all three state parks (at the time totaling 4,480 acres), together with other such areas as the Secretary of the Interior determined to be suitable for administration as part of the monument. [69] The NPS did not respond to Ullman's letter until March 6, one day before the newly-elected senator from Oregon, Robert Packwood, introduced an identical bill (S 1521) in the Senate. At this point NPS assistant director Theodor Swem wrote to Ullman and offered to resubmit the study team's evaluation to the Secretary's Advisory Board. Swem cautioned, however, that the board might again defer action without preparation of a master plan, something which the NPS could not undertake that year due to a backlog of other plans and studies. [70]

No hearings took place on the legislation, nor did the Department of the Interior have to prepare a report on either bill. [71] Their intent seemed to be served by stirring the NPS to schedule a master plan study for fiscal year 1970. [72] At first tentative, Ullman subsequently secured a NPS pledge of December 1970 for the study's completion date. [73]

Once state officials learned of this development, they urged Ullman to convey a couple of suggestions to NPS planners. One concerned allowing visitors "to explore for and remove token materials under appropriate special rules and regulations," as a way of enhancing the area's educational potential. The other pertained to naming the monument after Thomas Condon, as per a suggestion by the State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee. [74] Both ideas represented a move away from only cautious support expressed a few months earlier, and the noncommittal approach state parks personnel took during the evaluation study in 1967. [75]

After the master plan project had been activated by the NPS on August 12, 1969, its planners made a reconnaissance in order to prepare a planning directive. [76] This took place in March 1970, when a team mainly from the Western Service Center in San Francisco visited the upper John Day Basin. [77] Among the preliminary findings made in order to focus the planning directive, the team identified a need for centering visitor contact and interpretation, preferably where the broadest variety of features exist. They recognized that the upper basin did not intercept cross-country travelers, though this could change with development and public relations work. The planners acknowledged that visitors should have an opportunity to find and excavate fossils within a controlled area, as per the state's suggestion to Ullman. Since campgrounds existed on U.S. Forest Service land in the upper basin, they did not see a need for overnight camping within the proposed monument. The team also cautioned against any proposal involving large acquisitions of privately-owned bottomland. [78]

This reconnaissance also summarized four alternatives for possible NPS administration in the area. The first focused on the Sheep Rock area by itself, while the second centered on Sheep Rock and Clarno. A third alternative added Painted Hills to Sheep Rock and Clarno, but the fourth included all known points of geological interest in the upper basin. [79] Two months later Regional Director John Rutter approved the third alternative in the resulting planning directive, but with an understanding that "no area of special geological significance is ruled out at this time." [80]

|

| Sheep Rock as view from Cant Ranch. Since planners thought it dominated the scene along this portion of State Highway 19, they gave the name "Sheep Rock" to the prospective monument's largest unit. (photo by the author, 1992) |

Planning for a new park in an

era of expansion

Almost nothing had transpired since the NPS issued its directive for the John Day Fossil Beds master plan in May 1970, so Regional Director John Rutter called a meeting in his office on October 16 to develop the project further. [81] John Sage, of the Office of Environmental Planning and Design in the Western Service Center (WSC), joined Rutter at this meeting, as did Dan Burroughs from the Portland Field Office. [82] From it came some guidelines to direct the planning team's preparation of master plan documents. [83]

One of the key directives involved giving strong consideration to the town of Day as administrative headquarters. This is because the group envisioned a unit operation with Sheep Rock providing visitors with primary interpretation, Painted Hills accommodating campers, and Clarno serving as a day-use area. Rutter, Sage, and Burroughs also wanted the NPS to manage "the scattered and numerous regional features" which they thought should be considered for less-than-fee acquisition. [84] In most cases this meant scenic easements, whereby the property owner agreed to perpetuate agricultural uses on their land. This involved the purchase of development rights by the NPS, but on a willing seller basis.

The meeting's one reference to staffing concerned on-site employee housing which, in somewhat obvious terms, they saw as being determined by the extent of park development and a need for resource protection. By December 2, however, Rutter planned to place a ranger and a maintenance employee at each of the three units while stationing a superintendent, secretary, naturalist and/or protection specialist at John Day. At this time he also gave "general administration and housekeeping" responsibility for the proposed monument to the NPS group office in Klamath Falls. [85]

WSC's John Sage gave Rutter tentative boundaries for the proposed national monument on December 11, 1970. In wanting to consolidate features in each of the three units, Sage intended to simplify boundaries to the degree possible for management while providing enough area for development and protection of the visual scene. [86] This took the form of an oblong and contiguous unit of 16,300 acres at Sheep Rock. It included the 4,340 acres of state park land, public domain already in federal ownership and administered by the Bureau of Land Management, along with private parcels to be acquired in fee or through easements. He found the Painted Hills more problematic, as a need to acquire enough of Bridge Creek to permit overnight camping flew in the face of anticipated antagonism arising from the state prevailing in condemnation proceedings. In this unit Sage wanted to incorporate the state park with 1,400 acres of other lands for a total of 4,220 acres. In proposing 2,040 acres for the Clarno Unit, Sage omitted most of its geological features except for the Palisades. He admitted that perhaps this needed restudy, but his sentiments had more to do with bringing river recreation into the master plan, than paleontology. [87]

|

| The NPS proposed a campground for an area along the west bank of Bridge Creek, just south of the state picnic area, in all three drafts of its master plan for the prospective national monument. Planners eventually settled for improvements to the picnic area due to doubts about the need for camping at the monument. (photo by the author) |

Sage's ideas about boundaries carried into a management statement drafted at year end as part of the master plan. This document saw the region's geology and its interpretation as compatible with visitor use of the John Day River. Both of these might be better facilitated, it stated, by an opportunity to camp. [88]

Much of what had been outlined earlier appeared in January 1971 as a working draft of the master plan promised to Ullman a year earlier. [89] Although it had only nine pages of text and some maps showing boundaries of proposed units, Ullman wanted the draft so that he could introduce a new bill early in the 92nd Congress. The bill, HR 488, did not specify park size nor did it supply direction for how the prospective national monument should be administered. This is because such things as management objectives, it appeared, could be developed in the master plan. Proposals in this draft, as the planners put it, followed from three goals: to protect existing paleontological features, provide related comprehensive interpretation, and develop indigenous recreational assets. [90]

Ullman introduced his bill on January 22, 1971. A month later one of his staff members inquired about the next step in this master plan process. One of Rutter's subordinates replied that a finalized plan could serve as a basis for preparing the Department of the Interior's report on Ullman's bill, if the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs requested such a report. [91] During the next few months, little more than a restudy of the Sheep Rock Unit's boundaries took place until four NPS planners visited Grant and Wheeler counties in May 1971. [92]

Probably the most significant change to the park proposal arising from this visit involved excluding Camp Hancock from the Clarno Unit. Operated as a summer facility by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) since 1951, the camp attracts science students who range from elementary to graduate school. [93] NPS plans called for a ten acre exclusion from the monument, even though OMSI originally had a 40 acre lease from the Bureau of Land Management. [94] This stemmed, however, from a BLM determination in 1969 that OMSI's plans for development were inconsistent with its lease policy and therefore limited camp facilities to ten acres. [95]

Meanwhile, one state representative began preparing a bill that granted the highway commission authority to donate state parks for the purpose of establishing a national monument. [96] Despite a previous state attorney general's opinion that authority for such a transfer already existed, this bill made its way through the legislature partly because of concern that Ullman's bill in Congress had languished once again. [97] With three state parks in the upper John Day Basin specifically in mind, the state legislature passed HB 1223 in May and the governor signed it in June of 1971.

Previous indication of the state's willingness to donate these parks resulted in the Secretary of the Interior's Advisory Board endorsement of the proposed national monument in April. [98] The park proposal had solidified enough at this point for the NPS to present it as three noncontiguous units totaling 22,560 acres with a headquarters in John Day. Described as independent but complementary parts of a single entity, the NPS likened each of the three units to separately developed areas of a large national park. [99]

|

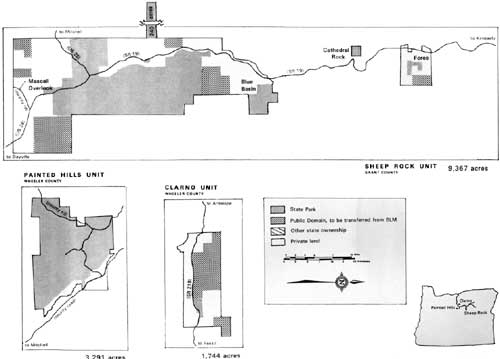

| Tentative boundaries for the proposed national monument encompassed 22,560 acres according to the NPS master plan dated January 1971. |

Ullman's scheduled visit to Oregon in August 1971 pushed the master plan draft closer to completion. [100] Work on cost estimates for land acquisition, staffing, and development began three weeks after a short field visit to the proposed monument by NPS planners in May. [101] These aspects dominated the master plan draft of August 1971, so much so that statements about the scope of resource management and the monument's purpose appeared vague by comparison.

Nevertheless, planners cited protection of fossil resources as being partly responsible for the master plan study. [102] In responding to threats previously outlined by Shotwell, such as the increased trade in fossils, planners stuck to broad generalities concerning the emphasis of resource management. Primary objectives centered on preservation and protection, along with interpretation of geological and paleontological features, though use of the John Day River also became a focus. [103] Since they knew that relatively small and widely separated units could not function as wildlife management areas, secondary resource management objectives focused on cooperating with other land managers to retain "a naturalistic landscape that complements the fossil story." [104] Planners pointed to NPS administrative policies for the natural area category for more specific management direction. [105]

NPS land acquisition plans reduced the proposed monument to 15,680 acres, as compared with 22,560 acres of a few months earlier. This is largely because the 9,922 acre Sheep Rock Unit now had three components: a contiguous tract from the Mascall Overlook to Blue Basin, a considerably smaller holding at Foree, and a 40 acre parcel at Cathedral Rock. Planners suggested a mix of existing state park land, fee acquisition (from private landowners and the Bureau of Land Management), and scenic easements at all three units. At the 4,093 acre Painted Hills Unit, for example, they proposed fee acquisition to buffer existing state park land (especially where bottomland along Bridge Creek bordered state holdings) whereas a scenic easement appeared sufficient for 800 acres east of the county access road. Curiously, however, the nut beds and mammal quarry were missing from the 1,665 acre Clarno Unit. The planners wanted little more than the Palisades, located in the 100 acre state park, which they described as the "primary Clarno formation." They proposed that 800 acres be acquired through scenic easement, but this largely constituted a buffer around existing state park land. In contrast to the plan for Painted Hills, the NPS aimed at public domain land for proposed fee acquisition at Clarno. Planners thought a small private tract south of State Highway 218, however, might have to be acquired in fee because it could provide visitors with river access.

This access point might then be developed into a primitive campground, like one the NPS planned for further upstream near Service Creek. [106] Nonetheless, most development at Clarno centered on day-use facilities at the Palisades, where the plan called for a picnic area and interpretive trail. The NPS had a more ambitious scheme for Painted Hills, where a visitor contact station, campground, amphitheatre, and trail system had been proposed. Plans for developing the Sheep Rock Unit bore a marked similarity to those previously formulated by the state, but the team justified a choice to make it the primary interpretive site for a number of reasons. Among them included its size relative to the other units, the variety of geological resources represented, this unit's land ownership pattern and relationship to the John Day River, as well as its location relative to highways in the region and to the town of John Day. [107] As a result, development of a visitor center, support facilities, river access, and trailheads all centered on the Sheep Rock Overlook. The planners recommended that other development in this unit be less intensive, in proposing only a picnic area and trail at Foree, tables and toilets at Johnny Kirk Spring, a trail at Blue Basin, and a vehicular trail" on the south side of Picture Gorge to provide safer access to viewpoints like the Mascall Overlook.

|

| Monument boundaries embraced a total of 15,680 acres in the August 1971 master plan draft. Note that the NPS split the proposed Sheep Rock Unit among parcels at Foree, Cathedral Rock, and contiguous tract extending from Blue Basin to Picture Gorge. Planners reduced the prospective Painted Hills Unit by omitting parts of its southeast corner, while also trimming the Clarno Unit by half a section. |

While the master plan draft received this substantial revision from what it had been in January, members of the planning team also responded to the Washington Office's request for legislative support data. [108] This bevy of documents could serve as the basis for Interior's position on Ullman's bill, but required planners to assemble a general development plan, development schedule, land cost estimate, staffing summary, visitation forecast, and other materials. Rutter felt confident that all requirements for legislative support data had been met by September 24. Three months later, however, Deputy Director Thomas Flynn cited problems with acreage figures and cost data, so he recommended that Interior defer submission of its report. [109] Despite this setback, members of the planning team finished a report on land appraisals the following March and a new development schedule in June 1972. [110]

Virtual completion of the legislative support data almost coincided with another draft of the master plan. In the nine months since the August 1971 version went out for review, there had been several changes. One involved boundary changes in all three units, whereby the proposed monument's total acreage dropped from 15,680 to 14,402 acres. [111] In another change, planners backed away from as much fee acquisition as had been proposed previously. They opted for management of public domain land within the proposed monument by interagency agreement. [112] Despite the trend away from fee acquisition, the planners proposed fee acquisition of the Cant Ranch buildings to provide a venue for interpretation and management in the Sheep Rock Unit. [113] The only other change involved reducing what had been a projected 150 site campground at Painted Hills to 75 sites. [114]

|

| Proposed boundaries in the NPS master plan draft of June 1972. Totaling 14,402 acres, these became the lines authorized by Congress two years later. Within the Sheep Rock Unit, reductions from the August 1971 plan took place at Foree. The largest drop in acreage, however, was at Painted Hills where planners brought back the eastern boundary to Bridge Creek. A focus on more river access led to a slight increase at Clarno. |

Despite the relatively small scale of changes since the August 1971 draft, several components of the master plan encountered resistance from BLM. Several of their field personnel in Oregon repeated concerns first expressed in June 1971 that the monument could have serious impact on use and administration of adjacent BLM land. [115] Specifically, the Prineville district manager thought any prohibition on grazing in the Sheep Rock Unit might result in added demand for forage on adjacent BLM parcels. He also thought the elimination of hunting at Clarno could bring increased competition between cattle and area wildlife. [116] More importantly for the master plan's scope, BLM managers questioned the propriety of NPS proposals to develop facilities on the John Day River. They could not see how these facilities related to Ullman's intent in HR 488 because river recreation bore little relation to "proper development of the unique paleontological and geological resources." [117]

As it turned out, BLM did not pursue the grazing concern. They also accepted a prohibition on hunting within the monument's boundaries, but the NPS agreed in August 1972 that hunters could have access to adjoining land providing they transported their firearms across the monument in an unloaded, broken-down, or properly cased condition. [118] In regard to developing facilities along the John Day River, the NPS decided to defer construction of a primitive campground at Clarno until determination could be made whether this section met criteria for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. [119]

Even though some agreement had been reached between the two agencies by September, this draft of the master plan remained on hold. The main reason appeared to be that the NPS wanted to coordinate completion of its master plan, legislative support documents, and an environmental impact statement (EIS) with preparation of a departmental report on HR 488. The House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs had requested the report, but it had to wait while the NPS solicited comments on its EIS from a number of federal, state, and local government agencies. Revised and enlarged somewhat from a September 1971 draft, this environmental statement essentially reiterated direction given in the June 1972 master plan. [120] Rutter sent the EIS to Washington on June 2, but a Federal Register notice inviting comment on it did not appear until November 4. [121] No real impediments surfaced, so the department approved the draft in January 1973. [122]

During the formulation and review stage of the EIS, however, the NPS dealt with several matters which indicated that several planning issues needed further clarification before congressional hearings took place. The first arose in February 1972 when state parks director David Talbot transmitted a recommendation from the State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee which suggested a name change from John Day to Thomas Condon Fossil Beds National Monument. [123] This idea went no further until one supporter sent letters to the two senators from Oregon, who then referred him to Interior. The department gave the letter to its board on geographic names, which sought guidance from the Oregon Board on Geographic Names. [124] In a memorandum to the NPS, the Interior board's secretary highlighted an Oregon board consensus that residents in Grant and Wheeler counties preferred the John Day name, even though some of them believed it to be overused. [125] The Oregon board eventually settled this question at its December 1, 1972, meeting. With NPS concurrence, they endorsed the name "John Day Fossil Beds National Monument" but urged that suitable recognition be given to Thomas Condon. Ullman thereby incorporated language stipulating that the Secretary of the Interior "shall designate some appropriate landmark, such as a visitor's information center, within the Monument area in recognition of the work of Thomas Condon" into a new bill (HR 1252) which he introduced on January 3, 1973. [126]

Another suggestion for a national recreation area surrounding the proposed monument led a considerably shorter life. As Ed Arnold of the Portland Field Office told Gordon Glass, such a change in the park proposal required starting anew with legislative support data, a master plan, and an EIS. Since the Grant County Planning Commission did not want further delay, they dropped further consideration of this idea. [127] Nevertheless, it surfaced again when two NPS representatives went to Canyon City in February to review the park proposal with local officials. The Oregon State Game Commission, who had been the originators of the idea for a national recreation area, believed that hunting could control deer-caused damage in bottomlands. They wanted the monument to embrace less acreage than the 14,400 proposed in order for control measures to be implemented. As an alternative to monument status for lands outside the state parks, the commission saw national recreation area designation as a way to permit hunting. [128]

With those sentiments expressed, the NPS representatives at this meeting found no actual opposition to the proposed monument. They realized, however, that some prime bottomland at Foree in the Sheep Rock Unit had inadvertently been included as a prospective acquisition in fee. As a result, they recommended a boundary revision for the Foree tract. In doing so, they found development of river access there to be impractical because of insufficient water, especially during irrigation season. [129]

These adjustments to the master plan seemed inconsequential until a month later, when the NPS began to find that some ownerships in the Sheep Rock Unit had changed over the past year. The first sign of trouble came just after the Canyon City meeting, when a new owner of 331 acres proposed for fee acquisition at Foree wrote to Ullman. In his letter, Bernard O'Rourke expressed alarm about the acquisition since he judged the remainder of his 700 acres as not viable for ranching without it. He asked for more information about Ullman's bill and whether public hearings on it might be held in Grant County, since the latter "would be essential to ensure that both the public and private land owners receive equitable consideration." [130]

This concern eventually led to more grassroots coordination by the NPS since Ullman wanted to smooth passage of HR 1252 by minimizing the fee acquisition of private holdings. [131] O'Rourke appeared to reach a compromise with NPS representatives Ed Arnold and Ernest Borgman on April 10, 1973, something which involved only 45 acres of fee acquisition and 290 acres in scenic easement. [132] A week later, however, they wrote to Rutter and explained that two other ownerships in the Sheep Rock Unit had recently changed and another landholder planned to sell. They saw each change as creating a high potential for conflict and the need to obtain the monument's authorization as soon as possible. [133] In response, Rutter urged Arnold and Borgman to proceed with contacting new owners so that they could be advised of the park proposal. [134]

As the link between NPS field activities and Washington, the regional office continued to coordinate updates on planning documents for the proposed monument. It now, however, moved away from sending planners on only occasional visits to the John Day country (where the NPS previously assumed it had unquestioned local support) toward more active involvement by two members of its planning team. Arnold took over for Burroughs as acting chief of the Portland office in early 1973, due to the latter's retirement. A few months earlier, Borgman likewise replaced Donald Spalding as general superintendent of the Klamath Falls Group. [135]

As a concept, the creation of group offices accelerated during Hartzog's tenure as NPS director because one of his reorganization studies recommended that small parks or NPS units in geographic proximity could be clustered. [136] Hartzog endorsed Spalding's idea of administering Crater Lake National Park, Oregon Caves National Monument, and Lava Beds National Monument from Klamath Falls, provided that each site retain some supervisory personnel on site. [137] Since Spalding had experience in new areas, he became Rutter's representative on the John Day evaluation study in 1967 and thereafter served as a member of the proposed monument's planning team. [138] Borgman's experience with new areas in Alaska and elsewhere made him a natural successor to Spalding, and coincided with a move by the regional director to exert more line authority over parks in the Klamath Falls cluster. These factors, and the need to work with local landowners contributed to Rutter giving Borgman more responsibility for the John Day project. [139]

Borgman and Arnold began talks with Sheep Rock Unit property holders in John Day on May 31,1973. [140] The two attended a meeting in Spray three weeks later, where they saw no objections to the proposed monument. [141] Arnold told a group of nearly 50 people at the gathering, "we are now ready, as near as I can perceive, to start legislative proceedings." [142] Ullman's representative at the meeting in Spray agreed with this assessment and thought the gathering had been helpful to the legislation introduced in January. [143] A representative from Senator Packwood's office, however, wanted to see more evidence of local support. [144]

In spite of this concern, Packwood and Oregon's other senator, Mark Hatfield, introduced an identical bill (S 2168) to Ullman's on July 13. [145] One day later, however, nine property owners in the Sheep Rock area signed a letter to Ullman which opposed prohibitions on grazing and hunting in the proposed monument, as well as scenic easements that "could in any way restrict or control agricultural uses." [146] Borgman responded by sending information on scenic easements to members of the group and, in a memorandum to Regional Director Rutter, recommended that plans for this type of acquisition be altered somewhat, particularly around Foree. [147] After attending two meetings with local ranchers in August, he also advised Rutter that some kind of arrangement could be worked out so that grazing might continue in the Sheep Rock Unit. [148] As for hunting, however, Borgman stood in firm opposition because this activity threatened the monument's viability. In addition, he and other NPS officials did not see how hunting opportunities or the area's deer populations could be significantly affected by national monument status. [149]

Further negotiation on these issues became necessary after Senator Packwood presided at an informal meeting on August 22, 1973, in Dayville. Approximately 150 people attended and approximately ten spoke. Most of the speakers expressed opposition to the proposed monument, which surprised Packwood because his correspondence had been running almost fully in favor of the project. Borgman read the situation as simply a lack of local support being expressed at the meeting, rather than clearcut opposition to the park proposal. [150]

Although he urged the monument's backers to assert themselves more, Borgman realized the necessity for a workable compromise with Sheep Rock area ranchers before congressional hearings on Ullman's bill took place. By the end of October, after another meeting in Dayville, several points of agreement had been reached. The NPS clarified restrictions on scenic easements by submitting a draft to the Sheep Rock landowners and agreed that hunting or predator control, in accordance with state regulations, could take place on these easements. Grazing privileges, as then existing, could continue except as might be voluntarily relinquished by the owner. The NPS also agreed to a minor boundary adjustment near the Mascall Overlook, deleting some acreage previously proposed for inclusion in the Sheep Rock Unit. [151] Accordingly, Ullman found these compromises acceptable and stated that open-ended language in HR 1252 allowing the Secretary of the Interior discretion to make boundary adjustments could be changed to limit such actions to minor ones. [152]

Borgman's most important negotiations (ones which he later remarked determined whether the NPS had a park or not) focused on acquisition of buildings at the Cant Ranch. [153] Talks with heirs Lillian Mascall and her brother, James Cant, Jr., began in May 1973, soon after their mother died. [154] During one of his visits with them in the following August, Borgman committed the NPS to an interpretive theme which included ranching history and the part ranching played in the dominant culture of north central Oregon He suggested the use of oral history in developing this theme, something which the owners of the Cant Ranch enthusiastically approved. [155] Neither Mascall nor Cant spoke in opposition to the proposed monument at Packwood's meeting in Dayville, and by early September one press account ran a photo of the ranchhouse as a prospective administrative office and exhibit building. [156] Although negotiations had really only begun at this point, Borgman's optimism could be more than guarded. The family needed money to pay inheritance taxes, something which made prospective preservation of the ranchhouse very inviting to them. [157] When Cant indicated a preference for selling the entire ranch rather than just part of it, Borgman told Ullman that this option or one involving a life estate might have to be worked into legislation. [158] The congressman did not see Cant's wishes as a problem, and in mid-November announced that agreement had been reached on a NPS plan for the proposed monument. [159]

|

| James Cant, Jr., Lillian Mascall, and Ernest Borgman at the Cant Ranch, August 1978. (NPS photo) |

Despite some objections raised by one landowner m the Clarno Unit about restrictions related to scenic easements, Ullman arranged for a hearing on HR 1252 in December by the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation. [160] What appeared to Borgman and Rutter as a bad omen, however, came in the form of a memorandum from Stanley Hulett, NPS associate director for legislation, on December 6. Hulett asked Rutter to submit "alternative management concepts" for the proposed monument, which he defined as proposals for less than total federal involvement at the site. The associate director wanted "overwhelming justification for transfer of the three state parks, rather than simply providing funds and technical assistance to the state. [161] Since Hulett asked a number of other questions concerning what the state had done in the past five years and about the necessity for NPS administration, Rutter sent him an interim reply on December 7. Rutter warned Hulett that the monument proposal "is now so far advanced and commitments so firm that any attempt to abandon it would be completely damaging to our credibility." [162] He further defended it by citing the area's national significance and its place in rounding out the National Park System. [163]

Three days later Hulett, through Assistant Secretary of the Interior John Kyl, recommended deferring action by the Congress on HR 1252. [164] Oddly enough, Hulett recommended that Interior submit a favorable report on the bill's predecessor, HR 488, submitted just over a year earlier. His subordinate, Ira Whitlock, submitted a favorable recommendation on HR 1252 on August 22, while in an acting capacity. [165] Nevertheless, the NPS officially remained uncertain as to whether a national monument represented the most advisable form of preservation. Hulett's stated reasons for this hesitancy included demands on the federal budget, the fact that over half of the proposed monument consisted of state park land, and concern about the state game commission's position on hunting. He did, however, pledge the administration's position on HR 1252 would be formulated by April 1974. [166]

As might be expected, both Ullman and Packwood testified in support of the bill. Ullman expressed dismay over the NPS recommending deferral, especially since he could cite planning documents and correspondence that addressed concerns which Hulett identified. Packwood read a shorter statement, largely confining himself to a testimonial about the fossil beds while also commending Ullman, the NPS, and local ranchers for their interest in protecting the area. [167] A representative of the National Parks and Conservation Association also spoke in favor of HR 1252, but recommended two changes. One involved using stream corridors to connect all three units of the monument, while also suggesting that the NPS minimize automobile- related developments through careful planning. [168]

The subcommittee chairman, Roy Taylor of North Carolina, concluded the hearing by charting this legislation's direction. He wanted to consider it again along with similar bills in order to report omnibus legislation in early 1974. Ullman commented that he had been pursuing national monument status for the John Day Fossil Beds too long to see it stymied by "bureaucratic indecision and the heavy hand of the Office of Management and Budget. " [169]

Despite this deferral, the proposed monument's master plan appeared to be moving toward completion. Rutter received word a few days before the hearing that the plan could be printed subject to a final review. [170] The regional director delegated this to Arnold, who in turn contacted Borgman. Both of them made corrections, but Borgman alerted Rutter that the master plan needed major revision. He strongly recommended it not be printed because the document did not reflect agreements that had been negotiated with affected landowners. Rather than put the cart before the horse, Borgman reasoned that a report to Congress made through Interior should reflect these agreements with supporting documents such as a master plan and environmental statement rewritten accordingly. He acknowledged that this endeavor involved a lot of work and expense, but saw dropping the John Day project as the only alternative. [171]

Rutter agreed with Borgman and stopped the master plan from going to press. The goal of completing it prior to further legislative proceedings had to therefore be abandoned. This is because the House subcommittee reconvened in late January 1974 to consider HR 1252 as part of an omnibus bill. The unfinished master plan did, however, provide direction for what the monument could encompass since Ullman's bill gave this authority to the Secretary of the Interior. It still represented a work in progress, but one which started to abandon a focus on recreational components, such as developing river access, in favor of strengthening justification for the monument based on preserving and interpreting scientific resources. [172]

Authorization and

establishment

The House Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation lost little time in approving Ullman's legislation to authorize the monument as part of HR l3157 after the second session of the 93rd Congress began in January 1974. In addition to John Day Fossil Beds, this omnibus bill included provisions to authorize five national historic sites: Clara Barton (Maryland), Knife River Indian Villages (North Dakota), Springfield Armory (Massachusetts), Tuskegee Institute (Alabama), and Martin Van Buren (New York). It cleared the Subcommittee on January 29 and then went to the full House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs for further consideration. [173] Ullman waited until June l3 for that body's approval because the committee had been considering a strip mining bill for most of the first half of 1974. [174]

When it came time for the bill to be reported, committee chairman James Haley said that Interior failed to deliver on its promise of a recommendation on national monument status for the John Day Fossil Beds. In a mild rebuke, Haley spoke for the committee in asserting its belief that Congress has the function of determining whether John Day Fossil Beds merited inclusion in the National Park System. [175] The committee reported favorably on the proposed monument, but also made reference to the Secretary of the Interior's Advisory Board recommendation in 1971 in substantiating this finding. HR 13157 passed the House as reported by voice vote on August 19. [176]

Once the bill reached the Senate, it took less than a month for a subcommittee hearing to be scheduled. All of the other prospective parks in HR l3157 had previously passed the Senate except for the John Day Fossil Beds, so the hearing had a single focus. It took place on September 13 before the seven member Senate Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation. Only three witnesses gave testimony in a meeting chaired by Senator Alan Bible of Nevada. The first witness, Douglas P. Wheeler, represented Interior and supported all of the areas proposed for authorization except John Day Fossil Beds. When Bible questioned him about the department's objection to this area, Wheeler replied that its resources already enjoyed protection as state parks thereby precluding the need for direct federal involvement. [177]

One of the subcommittee's members, Mark Hatfield, arrived after Wheeler voiced his objection to the proposed monument. Bible summarized the situation for him, whereupon Hatfield mentioned that he and his colleague from Oregon, Bob Packwood, had previously sponsored legislation to authorize John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in the Senate. Hatfield also referred to Ullman's sponsorship of the legislation in the House as evidence of support from the Oregon congressional delegation. After Bible cited the report by the Secretary's Advisory Board and the State of Oregon's backing for a national monument, Hatfield gave the gist of what the subcommittee had to consider:

Senator HATFIELD. Mr. Chairman, l think it comes down to a question before this committee as to the proper appreciation of a unique area that has been determined by many different studies to be very unique.

Second, the State of Oregon has in good faith acted to support these proposals and very frankly it seems to me that the bills as drafted both in the House and Senate by Congressman Ullman and Senator Packwood and myself recognize the considered judgment and study of people within the State and others as well, that this is the place and the way in which it is going to be best preserved and provided proper utilization for the public.

I would like to have the chance to read the objections and to know a little more in detail before l attempt to respond directly to those objections raised by the witness this morning.

Senator BIBLE. They are very short and they are over on the third page and you can read them while we are calling Senator Packwood.

Just as l stated l think you will find it a correct summary. But l would only have one further question of the witness and that would be this:

It seems to me that with both Senators from Oregon strongly in favor of this bill, that there is a reasonably good chance that the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument will be included in the bill. I would like to forecast that. [Laughter.]

Senator BIBLE. The question l would ask of you is this: If the committee should join in that type of thinking and put it in the omnibus bill, what would you recommend to the President as to signing or vetoing the omnibus bill?

Mr. WHEELER. l can see no reason to recommend a veto in light of the other items contained in that omnibus bill.

Senator BIBLE. That is the type of question and answer l wanted. Thank you very much. [Laughter.] [178]

This exchange virtually precluded the need for Packwood's testimony, which he submitted for the record without reading it. [179] Packwood did, however, speak to a couple of issues before Bible closed the hearing. He pointed out that the House-passed version of HR l3157 limited fee acquisition at John Day Fossil Beds to l,000 acres except by donation or exchange, whereas S 2168 (the bill which he and Hatfield introduced in 1973) had been open-ended. Bible then asked him whether he could accept the House version of the legislation, and Packwood had no difficulty in saying yes. Hatfield then joined Packwood in contesting the idea that existing state parks provided adequate protection for the fossils. Since much of this resource still lay in private ownership adjacent to state and federal lands, they argued for a single administrative unit to consolidate fossil-bearing lands within authorized boundaries of the proposed monument. [180]

After HR 13157 met with the subcommittee's approval, the full Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs unanimously ordered a favorable report on October 1. [181] At this point the Senate's report read very much like the earlier House report, except that reference to Interior's position on the John Day Fossil Beds legislation had been omitted. [182] The bill passed the full Senate on October 8, and it secured final congressional approval just nine days later. With the President's signature on HR 13157 now virtually assured, Ullman praised Hatfield for his efforts in guiding this legislation through the Senate. [183]

As signed by President Gerald Ford on October 26, 1974, P.L. 93-486 authorized the NPS to establish a John Day Fossil Beds National Monument consisting of 14,402 acres. Establishment, however, could not take place without donation of the three state parks. [184] Once an activation memorandum had been routed from Washington to Rutter, the NPS began negotiations for property transfers with the state. [185] State Parks Superintendent David Talbot recommended that the Oregon State Transportation Commission (the highway commission's successor) approve these transfers without cost on November 18, something which they approved a week later. [186]

Talbot wanted to give the deeds to the NPS at a ceremony in December, but technical aspects of the transfer delayed state approval of the deed drafts until June 1975. [187] During this six month period, the state decided to put a reversionary clause in the deeds, should the state park land cease to be used for national monument purposes. [188] Seeing no alternative short of a legislative act by the state for direct transfer without restriction, the NPS agreed to this condition. [189]

The deeds formally changed hands on July 1, 1975, at Lewis and Clark College in Portland. Ullman and Governor Robert Straub officiated at a brief ceremony which preceded formal dedication of nearby Tryon Creek State Park. Straub turned the deeds over to Ullman, who signed them as a representative of the federal government. [190]

Establishment of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument had to wait, however, for a Federal Register notice from the Department of the Interior to be published. Although the NPS notified the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs of its intent to establish the monument on June 27, the Federal Register notice did not appear for another three months. [191] Once it did on September 24, the somewhat anti-climactic establishment became effective fourteen days later on October 8, 1975. [192]

|

| John C. Merriam named Blue Basin for "a veritable labyrinth of canons, gulch and caves cut into the soft blue rock of the middle John Day beds by the heavy rains. The coloring of these beds is frequently most wonderful and of the most delicate shades. Passing along the bottom of any of the larger canons, the wilderness of finely sculpted and delicately tinted peaks and pinnacles about frequently causes one involuntarily to pause and gaze, astonished that even nature could produce such magnificent architecture." (photo by the author, 1992) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002