|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter Two:

ESTABLISHMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THREE STATE PARKS

At the time of its authorization in 1974, three state parks formed the heart of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Although the state's priorities for park development generally lay in other parts of Oregon, it acquired parkland in the upper John Day Basin over a 40 year period. This chapter begins by outlining how two Oregon State Highway Commission members provided a foundation for the state's park system to develop during the late 1920s. In doing so, they secured establishment of an area near Sheep Rock which, for most of its existence, constituted Oregon's second largest state park. Most of the state's efforts there (and at subsequently established parks at Painted Hills and Clarno) centered on land acquisition rather than development of visitor facilities. Management of these parks remained at a minimal level, a situation which allowed state officials to eventually become cautious supporters of national monument status for the John Day Fossil Beds.

Oregon's highway park system

Establishment of all three state parks took place during the period when the Oregon State Highway Department had oversight of state parks, a situation which lasted until 1979. [1] The state highway department (which has since been consolidated into the Oregon Department of Transportation) is not dependent on appropriations from the Oregon Legislature, being largely funded by gasoline taxes and automobile license fees. Overseeing it is the Oregon State Highway Commission (OSHC), a citizen body appointed by the governor since 1917. [2]

A park system tied to highways began in 1921, but did not gather momentum until state law authorized the OSHC to acquire right-of-way specifically for park purposes in 1925. [3] That year revenues from Oregon's gasoline tax began to support its highway system, which allowed state parks to have fairly stable funding until 1977. [4] Over this fifty year period, the acreage in Oregon's park system grew mainly through administrative fiat (in that state parks directors acted as agents for the OSHC in selecting and developing sites as parks) rather than from establishing individual parks through legislation. With more land in parks came increased use, and Oregon's system grew to become one of the most heavily used in the nation.

Two members of the OSHC furnished the spark for this to occur. Upon his appointment to the three member OSHC in July 1927, Robert W. Sawyer joined with chairman Henry B. Van Duzer to greatly increase the number of state park sites acquired during the next year and a half. The first two state parks in the upper John Day Basin appeared during this period, with both intended as small roadside rest areas. Shelton Wayside, located on what is now State Highway 19, began as a three acre gift from the Kinzua Lumber Company in 1927. [5] Another donor gave the state eight-tenths of an acre adjacent to Highway 19 at Johnny Kirk Spring a year later. [6]

Not only did Sawyer support having more areas, but he also wanted larger parks with adequate management. [7] Sawyer saw the highway department's engineers as primarily concerned with road building and maintenance, with little time to devote to parks. He did not, however, support taking the parks away from the highway department. Instead, Sawyer proposed that a superintendent be hired by the highway department to provide ongoing direction for the state parks. [8] He eventually prevailed upon Van Duzer, and in August 1929, they selected Samuel H. Boardman for the job of state parks superintendent.

Boardman served as superintendent until his retirement in 1950. He emphasized land acquisition, especially along the Oregon Coast, and is certainly the single greatest influence on what has become part of the state parks system. During his 21 years as superintendent, Boardman secured almost two-thirds of what now is a system of 90,000 acres. In doing this, he often exercised his ability to persuade property owners to give or sell land on generous terms for parks. [9]

|

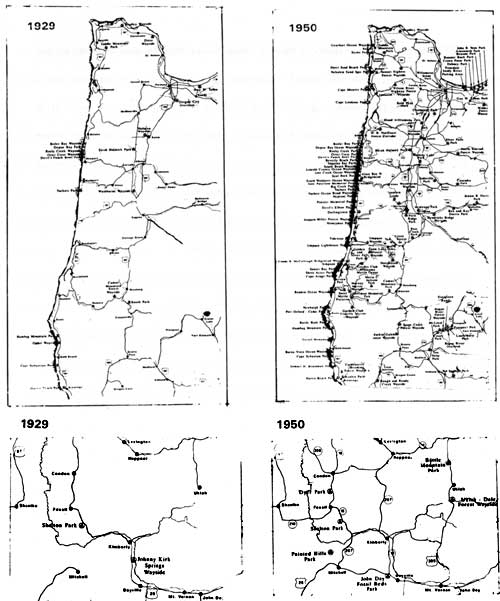

| State parks in the John Day Basin (bottom) at the beginning and end of Sam Boardman's tenure as the system's superintendent. Larger scale depictions of western Oregon (top) are shown for comparison to highlight how the number of state parks grew, especially on the Oregon Coast, over the same period. (from Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr., Oregon's Highway Park System, 1989) |

Establishment of a park near

Sheep Rock

Both Sawyer and Boardman played significant roles in building a state park in the area of what is now the monument's Sheep Rock Unit, but John C. Merriam initiated this effort once Congress passed the Recreation and Public Purposes Act on June 14, 1926. This legislation allowed unreserved federal lands to be sold to public agencies for recreational purposes at a price fixed by the Secretary of the Interior. [10] Merriam began working on a petition to the Secretary roughly two years later, making a request that public domain land around Picture Gorge be withdrawn for a state park. [11]

Merriam's fascination with the John Day Fossil Beds found new expression once he left the University of California to assume the Carnegie Institution of Washington's presidency in 1921. As a sort of gatekeeper until his retirement in 1938, Merriam headed one of the few funding sources available to investigators during a time before government grants pervaded scientific research. He capitalized on this position by coordinating a cooperative research program in the John Day Basin through making funds available to a small group of his proteges for studies in physical geology, paleobotany, and vertebrate paleontology. [12]

|

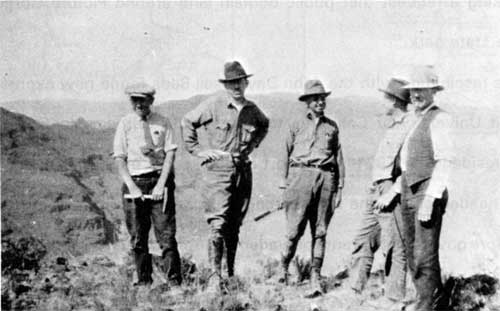

| As president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Merriam orchestrated a number of studies in the John Day Basin. He often combined business with pleasure during visits with colleagues whose research was supported by the foundation. Merriam brought his sons and sometimes met fellow scientists in the fossil beds, as shown by these photographs taken in 1923. From left to right in the top photo are Malcolm Merriam, Chester Stock, Eustace Furlong, Ralph Chaney, and John C. Merriam. The bottom photo shows him pointing to features in the field. (both courtesy of Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr.) |

To assist these investigations further, Merriam approached the U. S. Geological Survey to partially fund topographic mapping of the Mitchell and Picture Gorge quadrangles beginning in 1923. [13] One of his former graduate students, John P. Buwalda, directed the mapping which took place over the next several years. [14] In August 1927, Merriam alerted Buwalda that Sawyer wanted a recommendation concerning "areas in the John Day region most suitable for preservation as state or public property." [15] With Merriam's concurrence, Buwalda proposed that the focus be on an area encompassing Sheep Rock and Picture Gorge. Buwalda developed this further by recommending in a subsequent proposal that two or three sheltered "instruction stations" be built at suitable places along what is now US 26 and State Highway 19. [16]

Once Buwalda completed the Picture Gorge sheet a year later, Merriam outlined potential parkland for Sawyer and other OSHC members. In writing to Van Duzer, Merriam drew two boundary lines on an accompanying map. The outer boundary extended from rimrock to rimrock because it included the area which he thought should ultimately be preserved. An inner boundary represented what Merriam considered essential to the park, and focused on public domain land in two townships between Picture Gorge and Sheep Rock. [17]

By September 1928, the map had been sent to Sawyer in order for the highway department to ascertain ownership. A month later Sawyer drew up a petition requesting temporary withdrawal of all unreserved public land in the two townships Merriam identified. He then contacted former Oregon congressman Nicholas J. Sinnott, who relayed the petition to Secretary of the Interior Roy West. [18] Pending classification of the lands as recreational, the secretary agreed to recommend this withdrawal to President Calvin Coolidge.

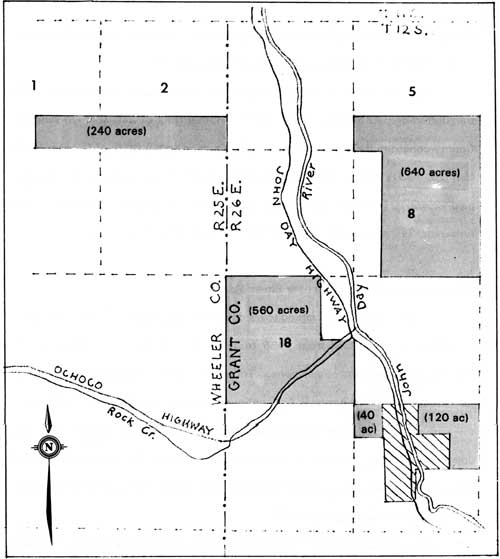

The state's application for permanent withdrawal of four parcels totaling 1600 acres (see Fig. 1), allowed the secretary to rescind his temporary withdrawal of other public domain lands in the two townships. [19] Upon the petition's receipt in Washington, Interior officials denied the state's application on part of one parcel, because a tract in Picture Gorge had previously been withdrawn as a potential power site. [20] Sawyer remained hopeful of acquiring the land around Sheep Rock and, in April 1930, sent a short note to Van Duzer suggesting that the park be named for Merriam. [21] His optimism, however, seems to have been dealt a blow upon learning what Interior's General Land Office (GLO) had classified as being chiefly valuable for recreation. GLO eliminated almost half of the remaining 1600 acres in the petition as being "rough and precipitous." Consequently, Sawyer asked Merriam to discuss this finding with GLO officials in Washington and reiterated the OSHC's interest in securing full title to all lands identified in the state's petition. [22]

Merriam wrote to the new secretary of the Interior, Ray Lyman Wilbur, about the proposed park's importance even before receiving Sawyer's letter. [23] Two weeks later, on May 31, Merriam sent another letter to the secretary. It questioned the GLO findings and asked for clarification about GLO's definition of recreation.

He defended the scenic and educational values of lands that had been classified as nonrecreational, characterizing these areas to be among the proposed park's most valuable parts. Merriam also relayed the OSHC request for an extension of the temporary withdrawal for the lands in question, so that the state could make another application for them. [24]

Wilbur's reply of June 6 granted the request for an extension. Sawyer's dismissal from the OSHC by incoming governor Walter Norblad less than a week later, however, dampered the good news. Although this constituted a blow to state park acquisition efforts, Merriam consoled Sawyer by writing that a good program prevails in the long run. [25] This optimism seemed at least partly justified several months later when Sawyer contacted Merriam with news that GLO had reversed its earlier decision and now classified the lands in question as recreational. Sawyer thanked Merriam for being the impetus in this process and assured him that the state could now proceed to secure all 1600 acres. [26]

When the OSHC attempted to purchase land under its petition, the GLO transferred only 1361.68 acres at first. [27] Another tract of 240 acres in Wheeler County constituted a separate entry on GLO's deed to the State of Oregon dated May 20, 1931, making a total of 1601.68 acres. [28] In this transaction the state paid $2002.10 ($1702.10 for parcels totaling 1361.68 acres plus $300.00 for the remaining 240 acres) and thus established Picture Gorge State Park. [29]

|

| Figure 1. The state petitioned for a total of 1,760 acres of public domain around Picture Gorge. Lands affected by the petition are shown by solid lines, forming squares in the sections indicated with numbers. The General Land Office eventually granted just over 1,600 acres of the petition, deleting 160 acres in Section 20 (shown by diagonal lines) previously withdrawn for its potential as a hydroelectric power site. |

Subsequent land acquisition

near Sheep Rock

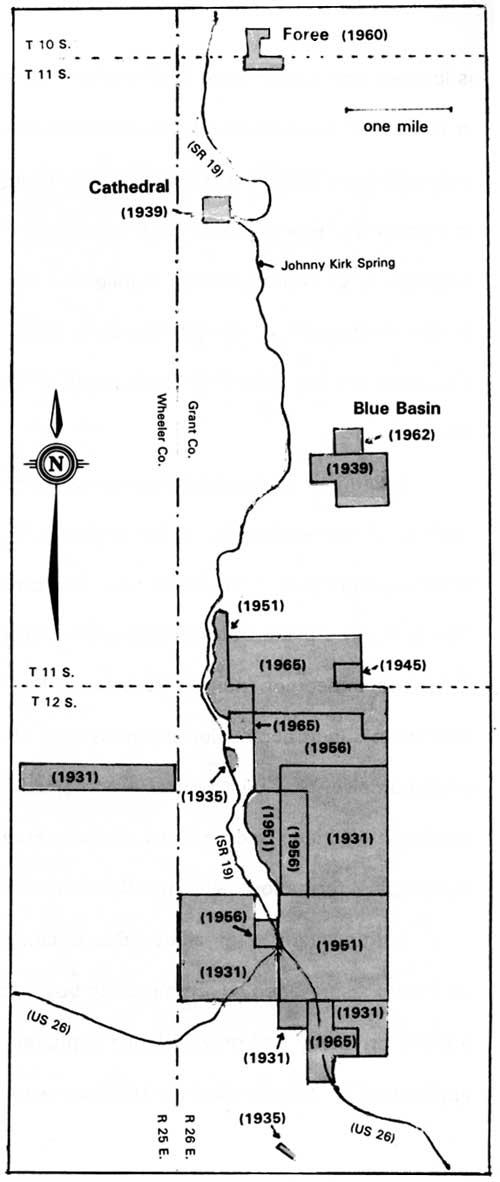

State parks officials worked toward assembling a relatively contiguous core area around Sheep Rock from 1935 to 1965, though five outlying tracts also represented significant acquisitions. Transfer of public domain land using the Recreation and Public Purposes Act continued to be a preferred method of building this park, though the OSHC also bought property from private landholders when the opportunity arose. In terms of size, this park maintained its position as second largest in the system, even though Oregon's state park acreage grew six-fold over a 30 year period ending in 1965. [30]

Land acquisition for Picture Gorge State Park actually began with a 1.5 acre gift from the Eastern Oregon Land Company (lineal successor to The Dalles Military Wagon Road Company) on January 31, 1931. Effective administration of this parcel as part of the larger park, however, did not prove to be practical because it is located seven miles east of Dayville. [31] Boardman made two more acquisitions in 1935 after some consultation with Merriam and Sawyer. The first came as a 3.8 acre gift from William R. Mascall for an easement leading to what later became known as the Mascall Overlook just south of Picture Gorge. Merriam spurred this acquisition, of course, having highlighted the site in a 1901 paper on the upper basin's geology. [32] At roughly the same time, Boardman also obtained a 4.5 acre viewpoint on the John Day River south of the Cant Ranch near State Highway 19. [33]

Boardman continued to buy several relatively small tracts of land near Sheep Rock for the next decade. In December 1937 he obtained the 40 acre Cathedral Tract through GLO. [34] A month later Boardman utilized the R&PP Act to acquire 200 acres in a place that Merriam and other members of the 1899 University of California expedition named Blue Basin. [35] World War II brought a hiatus to Boardman's land acquisition program until 1945, when the state purchased two small parcels. That year Boardman obtained the 40 acre Kennedy Tract one mile northeast of Sheep Rock, as well as three acres south of Kimberly which included a geological formation called the Davis Dike. [36]

Larger acquisitions eluded Boardman, despite the OSHC having approved their purchase. When he attempted to buy another 1600 acres from GLO in 1945, a stock driveway and grazing lease appeared to nullify, or at least postpone, the application. [37] Negotiations for 1000 acres of private property also stalled, largely because James Cant wanted twice what the OSHC had approved for three parcels totaling more than 800 acres. [38]

|

| State park land acquisition in the Sheep Rock area, 1931-1965. Tracts are shown with date of acquisition and in relation to the main highways. Note the emphasis on consolidation around Sheep Rock east of SR 19. The Davis Dike, a thre acre parcel near Kimberly obtained in 1945, is north of the area shown on map. |

Chester Armstrong succeeded Boardman in 1950 and served ten years as state parks superintendent. During this period land acquisition continued statewide, but at a slower pace because Armstrong emphasized developing the parks for overnight camping and other uses. [39] Even so, park acreage around Sheep Rock increased almost as much under Armstrong as it had under Boardman.

In 1951 the state bought 878.91 acres from James Cant, its largest single purchase from one holder other than GLO. This acquisition included three tracts of land located along the John Day River between Goose Rock and Picture Gorge. [40] The state turned to the Bureau of Land Management as successor to the GLO in 1956 to buy three parcels out of what Boardman had targeted a decade earlier, though these totaled only 640.44 acres. In spite of this acquisition amounting to only one section of land, it helped with infilling a core area begun with public domain land in 1931. [41] The purchase consisted of 40 acres in Picture Gorge, 160.44 acres that included Sheep Rock, and two other adjoining tracts totaling 440 acres. The state also obtained a portion of the Foree Ranch, that being a peripheral parcel of 69 acres north of the Cathedral Tract, before Armstrong retired in 1960. [42]

The remaining acquisitions near Sheep Rock took place from 1961 to 1965. This is a period when three different superintendents headed the state parks organization. All of them attempted to keep pace with rapidly escalating visitation by acquiring more land, something made possible through substantial budget increases from the Oregon Legislature during those years. [43] As a result, park acreage in Blue Basin grew in 1961-62 with the addition of 22.37 acres from the Munro Ranch and 40 acres from BLM. [44] The state made two additional acquisitions from BLM in 1965, transactions which further filled out the park's core area. It finally obtained the 160 acre reservation for a dam site in Picture Gorge, as well as 641.12 acres located in sections just north of Sheep Rock. By the end of 1965, the park totaled 4,344.68 acres, of which 3,323.24 acres had been acquired through use of the Recreation and Public Purposes Act.

|

| Visitors viewing Cathedral Rock, about 1955. (Oregon State Highway Division photo #5887) |

Park planning and development

near Sheep Rock

Long standing recognition of this park's significance did not prove sufficient to propel it upward among the state's priorities for developing visitor facilities. Several planning efforts appeared to promise better interpretation and public access to park features during the 1940s and 1950s, but demands on state parks in other parts of Oregon allowed for very little funding in the upper John Day Basin. Consequently, most of the state's modest investment in this park remained in land acquisition rather than development.

Boardman's emphasis on acquiring land furnished one reason why planning and development in the Oregon state parks generally stayed at minimal levels from 1929 to 1950. His pantheistic convictions also played a role, in that Boardman worried about overdevelopment leading to desecration of the parks. [45] In that vein, he saw federal relief programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as a potential problem if not given the proper guidance. [46]

Despite this concern, Boardman wanted to establish a CCC camp near Sheep Rock in October 1934 so that roads, trails, and parking places could be constructed in the park. He conferred with Merriam first, concerning how best to approach such development. [47] From a meeting in the field that summer came recommendations for acquiring a viewpoint along the highway across from Sheep Rock which could be furnished with a telescopic finder. Merriam also suggested obtaining an overlook on a bluff near the Mascall ranch house, and one atop a mesa located on the south side of Picture Gorge. [48] He agreed with his protege Chester Stock that there seemed to be little need for further development downstream, aside from where the highway approached Blue Basin and the Davis Dike. [49] Merriam did, however, propose that a simple building housing a few fossil specimens be erected at "some favorable place" to illustrate the story told in an interpretive booklet of not more than five pages in length. [50]

Boardman appeared to agree with the recommendations, but later claimed that Merriam's concern for protecting the fossils from public access prevented him from developing the park with CCC labor. [51] In fact, Merriam suggested that a survey of the park's roads and trails be made before using state highway equipment to make improvements. Boardman, however, limited work to the two areas that he acquired in 1935. [52] State crews completed a road from what subsequently became US 26 to the Mascall Overlook by 1938. [53] Also during this period they constructed a parking area just south of the Cant Ranch and adjacent to State Highway 19. Called the Sheep Rock Overlook, this site soon received a wooden signboard containing a short description of the area's geology. [54]

World War II virtually halted development in Oregon's state parks mainly because the CCC program ceased to exist after June 30, 1942. Planning efforts continued to some extent, and for Picture Gorge State Park in particular they took a relatively unusual direction. Merriam acted as a catalyst in 1941 by convincing the chancellor of the state's system of higher education to charter an advisory committee on educational problems in parks. Merriam served as a member of this group, as he had for a similar body sanctioned by the Secretary of the Interior to formulate guidelines for educational work in the national parks twelve years earlier. [55]

This allowed Merriam a quasi-official toehold in the state parks organization, one which he thought he strengthened by including Boardman on the committee. Academicians made up most of this group, which Merriam named the Committee on Educational Problems in Oregon Parks (CEPOP), though two National Park Service officials stationed at Crater Lake also served as members. [56] While CEPOP's scope encompassed the whole state, it emphasized the Columbia Gorge, Oregon Coast, and John Day region in carrying out a somewhat self-appointed mission. This included developing interpretive material for visitors, establishing exhibits and stopping places in or near parks, and taking measures to protect park areas. [57]

Merriam approached Boardman about sponsoring a booklet aimed at visitors to the upper John Day Basin as early as 1938, but did not begin writing in earnest until CEPOP passed a resolution endorsing publication of a guidebook in June 1942. [58] The committee believed this book to represent a first step in planning for a larger reservation and, if exceptionally well-written, might stimulate visitors to protect fossils and other park resources. As editor, Merriam titled the manuscript The Earth Shall Teach Thee and sent it to Boardman and OSHC members for review in August 1943. Upon receiving the OSHC's approval, however, he wanted to revise the material rather than take steps to find a publisher. [59] Merriam's failing health made him recommend that CEPOP take responsibility for the book, but nothing further happened and it remained unpublished. [60]

|

| John C. Merriam about 1935. (NPS files) |

Some discussion of exhibits for the park took place at the committee's June 1942 meeting, but nothing further resulted from a suggestion for a small display near the junction of what is now US 26 and State Highway 19. [61] This idea, however, developed by 1946 into a somewhat open-ended proposal for a museum. CEPOP member Luther Cressman from the University of Oregon intended the museum as a memorial to Merriam (who died in November 1945) and recommended that it be located near the highway junction, with responsibility for upkeep assigned to the state highway department. No further action could be taken until construction funds had been secured and a decision made as to what form this wayside museum might take. One concept involved installing open-air cases for the fossils, though other committee members favored erection of a building that permitted employment of a curator. [62]

|

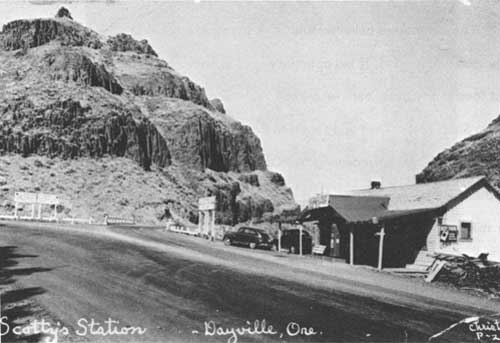

| The gas station and store owned by the Cants at the junction of US 26 and State Highway 19. One of the ideas discussed by the Committee on Educational Problems in Oregon Parks involved building a fossil exhibit nearby so that the station attendent could keep watch over it. (photo courtesy of Gwen Valade) |

Other than acquisition of acreage around the Davis Dike in 1945, little resulted from CEPOP's desire to secure stopping places in the upper John Day Basin. They wanted road markers to be placed throughout Grant and Wheeler counties to inform visitors about important geological features. Cressman intended to recruit Boardman or a highway department representative so that a marker could be designed and locations determined, but he did not make any further progress on this proposal. [63]

Discussion of how to protect the Sheep Rock area focused on how Picture Gorge State Park could be expanded into a parkway. When Boardman asked for the project's boundaries, the committee targeted a 22 mile section of the John Day Highway between Kimberly and the Mascall Ranch, the latter located one mile east of Picture Gorge. [64] This strip extended back from both sides of the river a width of one quarter mile beyond bluffs which border the John Day Valley. The committee recognized how diverse land ownership could be in such a large area and proposed management on a cooperative basis between public agencies (such as the state parks organization) and private owners. Specifically, they had no wish to disturb ownership of the cultivated bottomlands but suggested that easements might be obtained on other private tracts which could not be purchased in fee. [65]

Boardman, however, expressed his view that the state should own the land to protect it and asked committee members for advice on priorities for acquisition. Although Buwalda wanted an area from Mascall Ranch to Spray protected, he advised Boardman to buy land between the Humphrey Ranch near Goose Rock and the Foree Ranch. This is because the danger of desecration seemed to him to be the most serious in those two places. [66]

Merriam suggested buying parcels within the proposed parkway anytime one became available. This is perhaps because of his experience as president of the Save-the-Redwoods League in California, a post which he held from 1921 to 1944. As one of its founders, Merriam became a cornerstone behind an effort to buy redwood tracts on a willing seller basis with funds donated to the League. Once purchased, these parcels became part of the California State Park System. These efforts had resulted in four sizable state parks and the beginnings of others along US Highway 101. Merriam proposed a redwood parkway to protect and unify what had been acquired at a meeting of the California State Park Commission in 1933, but that body did not take action. [67]

Nevertheless, Merriam wanted to apply the parkway concept in Oregon. After CEPOP's June 15 meeting in Portland, Boardman arranged a luncheon for Merriam to present his ideas on it to OSHC chairman, Henry F. Cabell, and Boardman's boss, state highway engineer R.H. Baldock. [68] After Merriam presented the parkway project as a cooperative one, Cabell asked for a parallel case so that procedures could be studied for applicability to Oregon. Merriam cited what had been accomplished in the Lake District of northwest England through its National Trust, a private charity somewhat like the Save-the-Redwoods League. [69]

Even though Cabell expressed his enthusiasm for the parkway to Merriam, Boardman had his doubts. In October 1942 he wrote to Cabell and advised a slower approach, one which concentrated on the area between Blue Basin and Picture Gorge. Without directly criticizing Merriam, Boardman expressed concern that the parkway's size made it impractical even if an entity like the Carnegie Institution made matching funds for land acquisition available to the OSHC. Furthermore, Boardman recommended that no major development be made in this park until a revived CCC or similar work program came into being after the end of World War II. [70]

|

| John Day Fossil Beds State Park just north of Picture Gorge, about 1941. (Oregon State Highway Division photo #3485) |

By November 1942 CEPOP's John Day project took precedence over their interests in the Columbia Gorge and Oregon Coast. [71] This is because wartime made travel difficult and committee members thought it best to focus their energy on only one area. [72] Merriam began organizing what he called the John Day Associates as an extension of the project in April 1943, just as Governor Earl Snell appointed a new highway commission [.73] Once again Merriam's presentation about the John Day project seemed to make a favorable impression on the OSHC, enough to where CEPOP recommended that the John Day Associates be formally sponsored by the state's board of higher education. [74] Aimed primarily at better planning for individual studies and at facilitating cooperative research projects in the upper basin, Merriam also advocated the idea that investigators could function as semi-official park custodians responsible to Boardman. [75] Its membership overlapped somewhat with CEPOP, except that new members of the John Day Associates could be added from time to time. [76]

One of the few projects directly under the auspices of the John Day Associates involved one of their members, Eustace Furlong, who began compiling a master catalog of the upper basin's vertebrate fossils. He came close to completing the project, but a car accident in 1945 left him permanently incapacitated. [77] Less than a year later, the John Day Associates became publicly associated with protecting and expanding the existing park even though Merriam previously assigned this function to a CEPOP subcommittee composed of himself, Boardman, Sawyer, Cressman, CEPOP chairman Ralph Leighton, and Crater Lake National Park superintendent Ernest Leavitt. [78]

As a precursor to protection and expansion efforts, Merriam identified the educational features meriting preservation after his visit to the park in June 1943. Surprisingly enough, the list of what he considered most important fit within Boardman's scheme to fill out an area from Picture Gorge to just south of Goose Rock. Peripheral locales such as Blue Basin and Cathedral Rock had already been acquired, and Boardman later purchased the area around Davis Dike. Merriam, however, wrote to Boardman in July 1943 and wanted more of the Columbia lavas in the park and the Mascall formation's type locality southwest of Picture Gorge. [79] In a separate letter, Merriam also made a case for preservation of some neontological features. One unit included the flora of Rock Creek for a distance of ten miles upstream to a width of 100 feet on either side, while the other unit encompassed a belt of wild roses and associated plants which stretched a mile or more from Picture Gorge to the Mascall Ranch. [80]

Once land acquisition efforts could begin again in 1945, Boardman adopted some of Merriam's and the committee's suggestions with modifications and crafted his own recommendations for the park. Instead of acquiring ten miles along Rock Creek, Boardman supported having five miles. He reiterated CEPOP's support for a small museum at the highway junction, but redirected their focus on a guidebook and roadmarkers to a pamphlet keyed to highway mileposts. [81] Boardman also wanted a footbridge across the John Day River for access to Sheep Rock, something which represented a break from anything suggested previously. Another new recommendation involved building a catchment pond along the highway for runoff flowing from Blue Basin, in an effort to display the vivid green and red coloring evident after a rain. [82]

Boardman's plans for developing the park went unrealized as had those formulated by Merriam and CEPOP. Even so, another attempt to develop visitor facilities followed placement of a plaque by the Geological Society of the Oregon Country (GSOC) to commemorate Thomas Condon at the Sheep Rock Overlook on May 29, 1954. [83] At that time GSOC favored renaming the park for Condon, but Luther Cressman prevailed upon state parks superintendent Chester Armstrong to retain "John Day" in the name because of its established association with the area's formations. [84] Cressman also pressed Armstrong to construct an observation building at the overlook, a project which he envisioned to include a display of features relating to the fossil beds and a panorama depicting changes in the upper basin through geologic time.

|

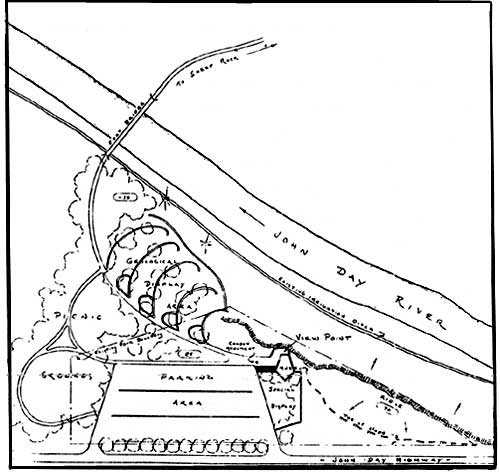

| Plan showing proposed development at Sheep Rock Overlook, 1954. (courtesy of Oregon Parks and Recreation Department) |

Planning for a museum and interpretive displays went to the conceptual stage with assistance rendered by J. Arnold Shotwell from the University of Oregon. As a result, Armstrong's draftsman prepared a drawing in December 1954 showing a small museum with an outdoor display, viewpoint, parking area, and picnic grounds within the tract purchased from James Cant in 1935. [85] A proposed footbridge for access to Sheep Rock and an area for geological displays bordered this proposed development on land not yet acquired by the state. The OSHC, however, elected not to fund implementation of the plan and it went no further. [86]

In 1957, the first formal administrative policy statement for Oregon state parks directed that they be developed to meet public recreational needs. Concern among prominent Grant County residents that the upper John Day Basin lacked recreational facilities, especially those for overnight camping, drove several investigations by state park planners from 1958 to 1961. Some land acquisition and small-scale developments in Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park followed, but the planners made little progress toward better facilities or interpretation.

State park planner Richard C. Dunlap visited the park in June 1958 and noted the lack of signage and facilities. He suggested a directional sign for the junction of US 26 and State Highway 19, in addition to one indicating "fossil beds" at Blue Basin. As for visitor facilities, only the rest area at Johnny Kirk Spring had a few picnic tables, pit toilets, and drinking water. He considered this site too small for overnight camping and thought that perhaps Blue Basin could be developed, though state property there had to be reached by a private road east of the highway. Dunlap found the Foree site, though not in state ownership, to be more advantageous. This locale might allow for developing a water supply, so that shade trees, restroom facilities, and picnic tables could be provided. [87]

More intensive study of camping followed in 1959 because visitors experienced difficulty in finding a public campsite within 50 miles of the park. Since anticipated use did not appear to support a very extensive development, planners saw the need for what they termed "minimum basic facilities." [88] Their report noted that a site near Blue Basin seemed to be the best choice, providing the additional land be acquired from the Munro Ranch. Despite some concern about the possibility of flash floods (or to use the local term, waterspouts), the state acquired a 22 acre parcel which allowed construction of a new entrance road, parking area, and "limited camping facilities" (pit toilets) by 1963. The state also obtained trail access through the Munro property by permit. [89]

The Foree locality became the venue for another minimum development because of its day use potential. In conjunction with acquiring 69 acres there in 1960, the state also obtained a permit granting public access on an entrance road extending from State Highway 19 to a prospective picnic area. Subsequent improvements at this site included a parking area, picnic tables, and pit toilets. [90]

Planners considered the scope of this development to be similar to Blue Basin, with the only difference being the availability of water at Foree. [91]

A more aggressive approach to planning for use in state parks culminated in 1962 with publication of Oregon Outdoor Recreation, a statewide study of nonurban parks and recreation. [92] The Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park drew some attention from planners who sought ways to facilitate interpretation of the area's natural features. A field inspection by Phillip W. Kearney in the spring of 1961 suggested that the Cant Ranch be acquired as park headquarters. He thought this might allow for a display area to be provided, in addition to a large picnic and camping area between the ranch house and the Sheep Rock Overlook. [93]

That summer a more definitive report by a landscape architect associated with the state parks, Walter S. Horchler, identified the park's greatest deficiency as visitors receiving little indication that they had entered an area of outstanding scientific significance. To remedy this in part, he suggested gateway signs on US 26 where Picture Gorge is entered from the east and west, as well as definition of a northern boundary on Highway 19. [94]

As for development, Horchler discouraged the notion of large facilities because he thought the park could not attract a great number of visitors to picnic nor camp for long periods. Horchler did, however, believe that an interpretive center containing "extensive exhibits and pictures of the archeological finds" might be situated at Sheep Rock Overlook. He thought this location to be preferable to the Cant Ranch because of costs and the existence of plans drawn in 1954. His only modification to these plans involved more landscaping with indigenous plants to soften the overlook's barren appearance. Rather than attempt to obtain an area around the ranch structures for a picnic area, Horchler suggested incorporation of picnic facilities into the interpretive center by means of "extended lanais" which could substitute for missing shade until planted locust trees obtained sufficient height. [95] He thought negotiations with the Cants might result in acquisition of several easements for one or more foot bridges to span the John Day River. From a parking area at each of these locations, visitors might then follow trails to view wayside exhibits. [96]

For a northern boundary of what Horchler called a "seemingly contiguous park unit," he recommended a privately-owned area near Goose Rock. Lying between the Munro and Humphrey ranches, this location left him with an impression of a sheltered cove with its shade trees and rock formations. After noting that the highway bend around Goose Rock opens to a full view of the valley ahead, Horchler endorsed acquisition of this parcel for a future picnic area. He also endorsed development of a very limited overnight camp there and made mention that its proximity to the river allowed for swimming below Goose Rock. [97]

Virtually nothing came of these recommendations for several reasons, with the first being visitation. Although this park's visitor numbers continued to grow at a significant rate from 1955 onward, Oregon's state park system experienced a tremendous surge in attendance during the 1950s and 1960s. [98] Visitation statewide numbered only two million in 1948, but grew to nine million in 1955, 16 million in 1965, and 19 million by 1967. [99]

This recreational demand centered on the Oregon Coast, which had to be center stage when the state parks organization used funds made available by the legislature for park development and land acquisition throughout the 1960s. Meanwhile, the responsibilities of the Oregon Parks and Recreation Division (OPRD) grew with passage of the federal Land and Water Conservation Act in 1964. As coordinator of matching grants to local governments, the division also assumed a lead role in statewide comprehensive recreation planning. This reinforced a preexisting recreational emphasis in state park planning, especially when David G. Talbot (who had joined OPRD in 1962 as state recreation director) became state parks superintendent in late 1964. [100]

Like his predecessors, Talbot desired to keep operation and maintenance costs low. In 1966 Oregon had the lowest park costs per visitor in the country at ten cents, as compared to a national average of 25 cents. [101] Given this ratio, it is not hard to understand why operation and maintenance costs at Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park that year did not exceed $1,200. Expenditures at a park where visitation never exceeded 20,000 in the 1960s reached a high point of $2,100 in 1967-68, but fell to 1966 levels the following year. [102]

Horchler identified education, which had to be inspired through interpretation, as the main focus for this park. [103] Initial efforts to provide interpretation in state parks began during the early 1960s at Fort Stevens State Park near Astoria, but this program limited itself to nature hikes and talks by seasonal employees. [104] Interpretation at Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park, as envisioned by Horchler and ethers, also involved construction of a visitor center containing valuable collections. In a state where these types of facilities existed only at Crater Lake National Park during the 1960s, such a proposal seemed out of the question.

Establishment of a park at

Painted Hills

Efforts to bring about a state park in the Painted Hills area lagged behind those at Sheep Rock largely because of the need for negotiations with private landowners. Despite this, the site appeared to have a secondary status to Sheep Rock in the minds of Merriam and Boardman. Neither of them attempted to acquire public domain land in the vicinity of Painted Hills as they had with the other state park. Nevertheless, each of them recognized that the Painted Hills locale could tell a story of evolutionary change through fossilized plants. Together with the scenic formation that provides this area with its name, both of them saw its scientific and scenic aspects as blending together in one state park.

Paleontologists have long known the vicinity of Painted Hills as the Bridge Creek locality. In the 1920s paleobotanist Ralph Chaney began comparing the fossilized Bridge Creek flora with modern redwood forests, work which soon linked his name with the area. [105] The park project began when Merriam mentioned a "redwood fossil area" located in the vicinity of Burnt Ranch during a three day trip with Boardman in 1938. [106] Merriam referred Boardman to Chaney, who gave him specifics about this locality, one which happened to be located near the Painted Hills. [107] Boardman inspected the area in May 1939, noting that almost half of the access road required widening, but appeared genuinely enthused about the suitability of Painted Hills as a state park. [108]

To establish the park, Boardman needed to do two things. The first involved obtaining OSHC approval. As a preliminary step, he solicited testimonials for Painted Hills from Chaney and Merriam before presenting this proposal to the commission. [109] Both letters alluded to how the geological past, as symbolized by fossilized redwood, contrasted with the juniper and sagebrush of the Painted Hills at present. Obviously these endorsements pointed to the proposed park's scientific value, but they also hinted at a link with the financing and public support behind California's redwood state parks.

Unlike the situation in California, however, Boardman could not call upon the Save-the-Redwoods League when attempting to acquire parkland. He soon found the asking price of two key landowners to be more than he or the OSHC found feasible, so park establishment had to be kept in abeyance until World War II ended. [110] Boardman kept himself informed about the situation through a contact in Mitchell, whereby he received notice that the two ownerships had been consolidated in early 1946 through sale to Lossie T. Howard. [111]

Boardman targeted a total of 2,822 acres owned by Howard to be included within the park, and also showed interest for a time in another 280 acres of public domain land. Fee simple acquisition of a picnic area along Bridge Creek became his highest priority because this could trigger improvement of a county road connecting Painted Hills with the Ochoco Highway. He selected an area of 13.2 acres for development, a site which supposedly coincided with where an expedition led by Merriam had camped in 1899. [112] Boardman did not object to continued grazing on the remaining 2,800 acres as long as Howard granted public access through a lease or some other means.

Since OSHC membership had changed since Boardman last presented the Painted Hills proposal in 1939, he found it advantageous to obtain another testimonial in addition to those previously submitted by Chaney and Merriam. Boardman recruited Phil Brogan, who worked for Sawyer as a newspaper reporter in Bend. Brogan had a long-standing interest in the upper John Day Basin and his articles on geology regularly appeared in several papers around the state. [113] Once OSHC members read Brogan's letter supporting Painted Hills as a state park at their meeting on October 28, 1946, they formally authorized Boardman to negotiate with Howard. [114]

Another six months elapsed before Boardman and Howard reached a final agreement. The state paid $66.00 for the 13.2 acre picnic site on condition that OSHC fence this area with woven wire and provide the entrances with cattle guards. OSHC also obtained full use of a private road one-eighth of a mile in length that connected the picnic site with the county road. The state also agreed to install no more than four additional cattleguards if and when necessary at points to be designated by Howard. [115] As for the remaining 2,822 acres, the state obtained a recreational easement since Howard feared that a long-term lease might cloud his title or interfere with a subsequent sale of the property. [116] Howard retained grazing and mineral rights, but the public obtained access to the land under easement. Fossils and "other objects of interest" could not be removed for commercial purposes. [117]

|

| Painted Hills State Park about 1950. (NPS files) |

Land issues at Painted Hills

State control and public access to the park became problematic as soon as Howard sold his property in 1951. Periodic difficulties with the subsequent landowner came to a head fifteen years later, with the OSHC opting to buy acreage under easement as a result. When negotiations eventually broke down, the state initiated condemnation proceedings which culminated in 1971. Acquiring fee title to the 2,822 acres in dispute, however, did not put an end to concerns about -protection of scenic and fossil resources.

The trouble began when a state park field examiner reported part of the picnic area to be under cultivation in April 1952. In addition, some 500 feet of fence separating the tract from adjacent farm land had been removed by landowners Charles Lang and Clarence Hudspeth. [118] Ownership of the fence continued to be an issue throughout the following year and became something which Lang and Hudspeth saw as related to having access to Bridge Creek for their cattle. [119] The state responded by fencing along property lines of the picnic area and appeared to have resolved the matter.

In 1960, however, Hudspeth posted a "No Trespassing" sign along the county road in an attempt to stop public access to the land under easement. [120] State parks superintendent Chester Armstrong asked him to remove the sign, which eventually reappeared in the form of a barrier in 1965. [121] At this point Hudspeth claimed that repeated incursions by hunters forced him to close the county road. After contacting the Wheeler County Court, deputy state parks superintendent L.V. Koons effected removal of the barrier. Although Koons tried to express his sympathy about Hudspeth's problems with hunters, their telephone conversation became confrontational once Koons maintained that the park would remain open. [122]

The situation escalated in May 1966 when a member of the state parks advisory committee reported Hudspeth using bulldozers to shove down tops of the Painted Hills. [123] Field inspection revealed that roughly five to ten acres had been leveled on a hill about one mile southwest of the state's lookout point. Excavation ceased where Hudspeth hit rock, but Koons treated this activity as harassment and contacted the highway department's legal division to see what could be done about it. [124] Upon review of the transaction with Howard, they advised Koons that the state's hold on the property might be tenuous if a case concerning control of the easement went to court. [125] The state thus began negotiations to buy the property contingent on OSHC approval of a purchase price. [126]

The commission granted approval to acquire the land under easement by condemnation because a change in ownership and failure to agree on a price hindered negotiations. [127] Although the Circle Bar Cattle Company (CBC) had since succeeded Hudspeth as owner, abuses related to off-road vehicle use continued. [128] Receipt of a $30,000 Land and Water Conservation Fund grant to acquire the property in 1967 made the state's pursuit of condemnation proceedings easier, but it took until early 1971 to secure final judgment. [129] For $37,200.00, the state extinguished all encumbrances on the land under easement except for public utility rights of way and an easement granted to CBC for passage of stock and equipment along the county road connecting Painted Hills with US 26. [130]

After assuming control of the property, the state fenced it against off-road vehicles. Little could be done to stop visitors or wildlife from climbing the Painted Hills, however, because the state did not have a resident caretaker. [131]

|

| Painted Hills State Park. The shaded portion is the state's picnic area, where it had fee title, but only a recreational easement on the remaining 2,822 acres until 1971 when it secured full title through condemnation. Bridge Creek is represented by a broken line because that portion of it is intermittent. County roads are shown by double lines, while unimproved access is indicated with dashed lines. Leaf Fossil Hill is identified because it represents the Bridge Creek Flora's type locality. |

Park planning and development

at Painted Hills

In comparison to the Sheep Rock area, planning efforts at Painted Hills could be characterized as minuscule. This is mainly because the state had only its picnic area in fee simple ownership until 1971. Consequently, park development did not go beyond occasional roadwork and the basic facilities provided at the picnic area. A single sign represented the extent of on-site interpretation, though there appears to have been some support for wayside exhibits along park roads as the condemnation proceedings neared their end.

Some estimates for roadwork and facilities in the proposed picnic area had been generated in 1947 when Boardman brought about the park's establishment, but the state could pay little attention to them until 1949. That year Wheeler County crews began widening the access road so that work on the picnic area began in September. [132] Boardman insisted on an austere development composed of several tables, two pit toilets, and a stove. [133] The chronically tight budget, coupled with Boardman's conviction that man-made things should never deface the park, apparently nixed recommendations for improvements from Armstrong. These involved placement of directional signs at road junctions, wayside markers near the park's points of interest, and trees in the picnic area. [134]

Armstrong, however, orchestrated some development at Painted Hills upon assuming Boardman's post as state parks superintendent in 1950. He had a sign on the Ochoco Highway enlarged and two others in the park replaced. The new parks superintendent also ordered that several turnouts be constructed at points of interest throughout the park. [135] Preparation of text for a geological marker began in February 1951, but differences over wording delayed its placement in the picnic area. [136] Some trees appear to have been planted at the picnic area around this time, because there was mention of Russian olives and an elm tree as being able to eventually provide shade in a 1961 field inspection. [137]

Armstrong's emphasis on overnight camping in the state parks is probably the reason why Painted Hills found its way onto a list of campgrounds in the State Parks and Recreation Division's report for 1957. A 1959 study of proposed development in Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds State Park, however, placed facilities at Painted Hills in the day-use category. [138] Visitor facilities at Painted Hills in 1961 consisted of two picnic tables, a hand pump, and two pit toilets. [139] Annual operating costs amounted to only several hundred dollars, though Armstrong noted that stock grazing and periodic flooding of Bridge Creek made it difficult to maintain facilities at the park. [140]

Little changed at Painted Hills during the 1960s in spite of developments in other state parks. Tests showing impure water resulted in the pump's removal in the summer of 1968. [141] That fall a new sign replaced the geology marker in the picnic area, though the wording remained identical. [142] When the state finally acquired the entire park in 1971, it proceeded to install roughly 11,000 lineal feet of fence to protect the hills from off-road vehicles and posted five signs which listed park regulations. [143] Apart from these measures, however, state parks officials made little headway toward developing the land formerly under easement. Near the end of condemnation proceedings, they had hoped to improve it for interpretive, scenic, and scientific purposes utilizing the existing roads and major viewpoint, but fell short of their goal. [144]

Establishment of a park at

Clarno

Even though several significant paleontological finds had previously been made around Clarno, this area did not interest the state until the early 1960s. [145] At that point the proposed park's rock formations, not its fossils, took center stage because of their proximity to State Highway 218. As a result, the state targeted only 100 acres for this park and saw it as little more than a wayside.

The possibility of acquiring a 22 acre parcel by donation appears to have given preliminary park planning some impetus in 1962. [146] On July 11, 1963, the Frank W. Lee family donated this tract with two conditions. In addition to installing a bronze plaque to Lee's memory within the parcel, state officials also agreed to "Clarno State Park" as the park's official name. [147]

The state once again utilized the Recreation and Public Purposes Act in negotiating a twenty year lease of public domain land. Located west of the donated parcel, this 40 acre tract cost the state $50.00 every five years in rental fees beginning January 20, 1965. [148] Nine months later, state parks officials bought land located between the leased tract and the donated parcel. [149] After paying the holder $760.00 for 38 acres, the state had a park which one writer described as being "geared to the pleasures and fascinations of geology as well as recreation." [150]

|

| Clarno State Park. The area delineated by broken lines and State Highway 218 is approximately 100 acres. It includes the 40 acre parcel marked "U.S." which the state leased under the R&PP Act. |

Park planning and development

at Clarno

Steep terrain and lack of shade ruled out camping, so the state concentrated on providing a day-use area for travelers wanting to leave the highway in order to view the Palisades. [151] To be located on the leased tract, plans for this development in 1962 involved a fountain, toilet facilities, a parking area of 12,000 square feet, and an entrance road. [152] An interpretive sign represented the only other development suggested prior to the park s establishment. [153] The marker did not materialize, but by 1973 the state possessed a rudimentary day-use area. Roughly two acres in size, it contained a parking area, as well as a pair of pit toilets, several signs, and some picnic tables. [154]

|

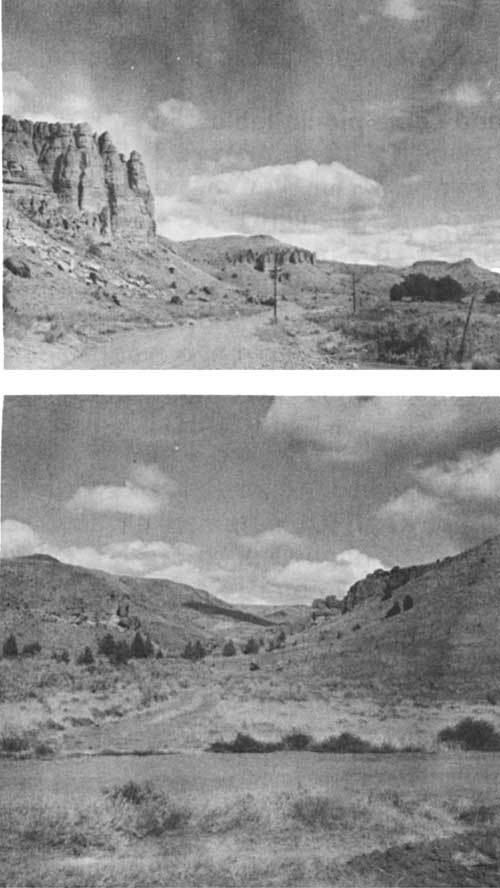

| The Palisades from State Highway 218 (top) and a view up Indian Canyon near the subsequently developed picnic area (bottom), both taken in 1962. (Oregon State Highway Division photos by K.A. Chatwood) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002