|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

Chapter One:

HISTORICAL BACKDROP

This chapter summarizes the pertinent historical patterns and events that predate establishment of state parks in the upper John Day Basin. It focuses on four broad areas which affect management of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. The first section outlines what is known about tribal territories in this part of Oregon to provide some context for consultation efforts. This is followed by a short narrative on subsequent settlement and land use intended to convey how the area's economic base developed in relation to the monument. In the third section, increasing recognition of the area's fossil resources over a 50 year period led to a short-lived national park proposal for the Sheep Rock area. The upper basin's prospects to obtain better roads fueled the park proposal at a time when automobiles began to gain widespread acceptance, so the fourth section describes how highways developed in Grant and Wheeler counties.

Tribal territories

Consultation efforts with Indian groups affiliated with the upper John Day Basin are complicated by uncertain territorial affiliations and overlapping areas affected by treaties. Two groups, the Tenino and the Northern Paiute, appear to be the most closely connected with lands comprising John Day Fossil Beds National Monument during the protohistoric (about 1730 to 1810, or the time between acquisition of horses and first contact with non-lndians) and historic periods. The two peoples, however, have had considerably different experiences in treaty-making with the federal government.

Indians have lived in what is now called Oregon for more than 10,000 years. Throughout this time territorial boundaries have fluctuated, but probably became more pronounced in the protohistoric period, due to increased mobility provided by the acquisition of horses. European-introduced diseases from roughly 1800 onward brought further territorial instability by decimating a number of Pacific Northwest tribes. [1] The changes brought by contact with non-lndians encouraged loosely affiliated bands to begin working together (and even confederate in some instances) for the purposes of maintaining trade, making treaties, or protecting home territory. [2]

Anthropologists have divided Oregon into a number of traditional culture areas in order to describe similarities and differences among aboriginal groups. Much of the basis for differentiating between two culture areas is physiographic due to the natural environment's obvious importance, but there is also a distinct linguistic division along these lines east of the Cascade Range. The Columbia Plateau culture area encompasses much of the John Day Basin and refers to a region where groups spoke languages classified as being part of the Sahaptian family and Penutian phylum. South of them is the Great Basin culture area, a region of interior drainage which extends from southeastern Oregon into Nevada and adjacent states, where Indians spoke Shoshonean languages of the Uto-Tanoan phylum. A border between Columbia Plateau and Great Basin culture areas is, however, less rigid than other culture area borders in Oregon because of comparatively sparse food resources and therefore few permanent settlements. [3]

|

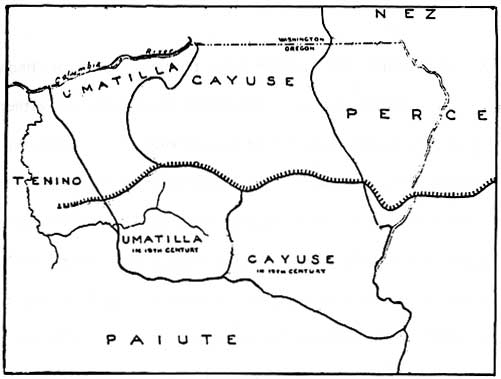

| Hypothesied tribal distribution in northeastern Oregon during the 18th and 19th centuries. Serrated line represents northern boundary of Paiute peoples in the 18th century and earlier. Note how the John Day River is used to divide the Umatilla and Cayuse from the Paiute, as well as the uncertainty over the boundary between the Tenino and Paiute. (from Verne F. Ray, et al., "Tribal Distribution in Eastern Oregon and Adjacent Regions," 1938). |

The upper John Day Basin is part of this transition zone, where the Tenino and other Plateau peoples sometimes collided with Northern Paiute bands from the Great Basin. Northern Paiute appear to have been the primary occupiers of the Sheep Rock Unit in the early historic period, though one or several Penutian-speaking groups may have been in the area at various times. [4] Among the latter are Tenino, Umatilla, Molala, Wasco, Cayuse, and Nez Perce. [5] Both Painted Hills and Clarno appear to be within the Tenino culture area because this tribe vigorously expanded up river following their acquisition of horses. Overlap with Umatilla territory in what is now Wheeler County during this period, however, makes exact determinations tenuous, as does a record of skirmishes between the Paiute and their northern neighbors in which no conquest followed on either side. [6]

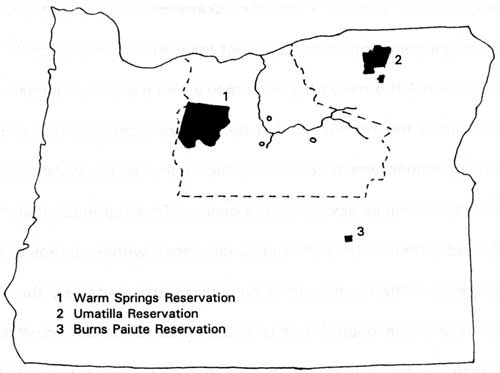

Two treaties of 1855 have the potential to affect monument lands. All three park units are within the territory ceded by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, an amalgamation which consists of the Tygh, Tenino, Wyam, John Day, and Wasco tribes, as well as several Paiute bands. These groups retain the right to fish, hunt, and gather berries at traditional places within aboriginal territory delineated by treaty. The monument is outside an area ceded by the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla people, but is within their larger aboriginal territory. Treaty rights accorded this confederation, however, do not appear as extensive as those for the Warm Springs. [7] Leaders of seven Northern Paiute bands signed a treaty in 1868. They did not cede any land, and the treaty remained unratified. [8]

|

| Indian reservations in the vicinity of the monument. A dotted line indicates Warm Springs ceded lands. The John Day River and units of the monument (indicated in circles) are shown as reference points. (derived from Jeff Zucker, et al., Oregon Indians: Culture, History and Current Affairs, 1983). |

Settlement and Land Use

Indian treaties aided white settlement in the upper John Day Basin, but distance to markets, semi-arid climate, and a limited resource base stifled population growth. Despite these limitations, a relatively stable rural economy based on livestock grazing prevails around Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno, as it does elsewhere in the upper basin at present. Consequently, a number of property owners around John Day Fossil Beds National Monument have been in the area for several generations and a few of them are descendants of the first settlers.

The upper John Day Basin drew miners following the gold strike of 1862 on Canyon Creek. As a result, Canyon City and John Day became main centers in the region. Most of the subsequent mining activity centered on a "gold belt" east of these towns in the Blue Mountains. [9] Miners rarely became long-term residents, but their need for supplies provided some impetus for settlement along the route of The Dalles Military Wagon Road--a lifeline that linked Canyon City and John Day with the Columbia River. [10] Limited access to outside markets made the grazing of livestock in the upper basin a local enterprise until 1880, partly because conflicts with the Northern Paiute hampered homesteading efforts throughout the 1870s. Despite these impediments, however, white settlers reached the vicinity of Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno by 1868. [11]

Most of these early settlers had their origins in the Ohio Valley and upland South. The 1880 census indicates that a majority of residents in this part of Oregon had been born in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois and Ohio. [(2] Overwhelmingly and persistently agricultural by occupation, these people had little trouble adapting to isolated farmsteads made viable by some grazing animals and a kitchen garden. [13] Like their southern relatives and largely Scots-lrish forebears, most affiliated themselves with Baptist, Methodist, or Presbyterian churches. [14]

An explosion in sheep grazing throughout eastern Oregon after 1880 followed the imposition of a tariff on foreign wool. [15] The height of this boom occurred between 1890 and 1910, when a number of Scots migrated to the region to work as sheepherders. They became the most distinct group in a second wave of newcomers to the upper basin, being particularly evident around Dayville. There they found few obstacles to integration with members of an isolated and agrarian society who, by 1900, had largely been born in Oregon. [16]

Sheepherders grazed their flocks on the public domain, often ranging some distance from a home ranch located next to a water supply. Like other places in the arid West, control of springs or other water had the effect of controlling the surrounding land base. [17] At first an abundance of bunchgrass on the open range made the bringing of sheep to the ranches unnecessary. By 1900, however, so much of the native grass had disappeared from the range in the upper John Day Basin that some visitors described unfenced areas as having been denuded by sheep. [18] Bad winters and the depletion of bunchgrasses necessitated the development of hay crops in riverine areas. [19] The extensive Allen Ranch (part of which is now the monument's Painted Hills Unit) had gone, for example, to cultivating alfalfa in the bottomland of Bridge Creek in 1899. [20]

During this period some ranch owners expanded their holdings by buying homesteads from their hired help. [21] Ranch holdings also grew from the failure of homesteaders to farm marginal lands, particularly during the decade following passage of the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. [22] The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 authorized closure of public domain land from further nonmineral entry, though the number and size of private holdings near the present national monument had stabilized by 1925.

A gradual shift from sheep toward cattle in the upper basin continued until the end of World War II due to market conditions and implementation of leases to graze public land. [23] By 1946 even James Cant and other Scots who came to the Dayville area during the era of wool tariff had switched. [24] Even so, this had little effect on persistently low land values in the vicinity of what is now the monument. This has made it easier for property owners to sell or donate lands for park purposes, especially if the transactions did not constitute large scale interference with grazing. [25]

|

| Homestead in Butler Basin area near Sheep Rock, ca. 1890. (NPS files) |

Fossil finds lead to the first park proposal

Soon after its discovery, the John Day Fossil Beds supplied a number of species and genera previously unknown to paleontology. By 1900 over 100 scientific papers had been published about the upper basin and most major museums in the world had collections from there. [26] An important find made near Picture Gorge in 1916 contributed to a suggestion that a national park be established in the Sheep Rock area. Although little more than a local newspaper editorial supported the proposal, it signaled local recognition that the fossil beds could attract tourists to the area.

Hostilities between the Northern Paiute and Euro-American newcomers throughout eastern Oregon became the catalyst for discovery of fossil plant and animal remains in the upper John Day Basin. A military detachment at Fort Dalles under Captain John M. Drake's command brought back fossils from an area 30 miles southwest of Sheep Rock in 1864. [27] The next year Thomas Condon, a geologist and Congregational minister from The Dalles, secured permission to accompany a cavalry unit into this area. Condon subsequently made finds along Bridge Creek near the present Painted Hills Unit and around Sheep Rock, in a locale he called Turtle Cove.

In 1870 Condon brought the John Day Basin to the attention of science through paleontologist Joseph Leidy. [28] By making the first study collections for this part of Oregon, Condon induced several leading paleontologists to visit the upper basin. One of them, Othniel C. Marsh, utilized a specimen collected by Condon to decipher horse geneology and in so doing made a significant contribution to evolutionary theory. [29] Marsh is also credited with bestowing the name "John Day Fossil Beds" in 1875. [30] Over the next 15 years, a number of fossil collectors such as Charles Sternberg, Leander Davis, William Day, and Captain Charles E. Bendire visited the upper basin. Although about 100 papers had been written on the upper basin by 1900, virtually all of them concentrated on naming new genera and species rather than relating them to the basin's geological record. [31]

After leading the University of California expeditions in 1899 and 1900, John C. Merriam became the first person to depict the relationship between stratigraphic sequence and the basin's vertebrate faunas. [32] In doing so, he named the Clarno, Mascall, and Rattlesnake formations and laid the foundation for subsequent studies in the area. This achievement and his subsequent efforts to establish state parks there made him the most prominent figure associated with the John Day Fossil Beds during the first half of the twentieth century. [33]

|

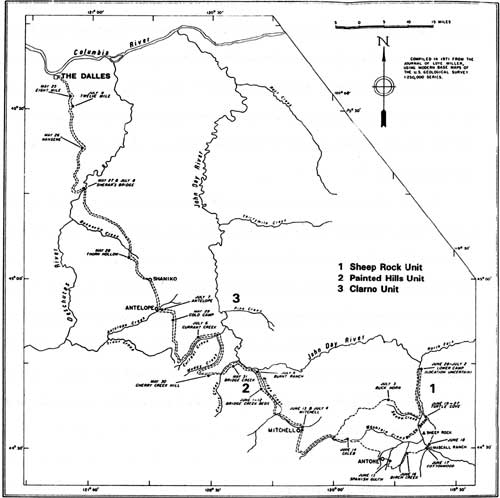

| Route of the first expedition led by John C. Merriam. It corresponded closely to the Dalles Military Wagon Road except for their trek into the Butler Basin, and back to Celeb. (from J. Arnold Shotwell, University of Oregon Museum of Natural History Bulletin No. 19, 1972) |

Anticipation of automobiles reaching the Sheep Rock area led a John Day newspaper in December 1916 to propose that part of western Grant County become a national park. [34] According to this editorial, the basis for the park consisted of public domain lands totaling two townships which the federal government could withhold from prospective settlers. The writer justified this proposal in economic terms, contrasting scenic and scientific values of the area's fossil beds with their having little or no value for grazing or crops. [35]

This proposal coincided with announcement of a significant paleontological discovery made the previous summer. Fragments from a Pliocene bear found just south of Picture Gorge generated some publicity after a paper with Merriam as lead author described them in November 1916. [36] At a time when the idea of continental drift still struggled to win widespread acceptance, the find matched a fossil previously unearthed in India and implied that Asia and North America had once been joined. [37]

Nonetheless, this proposal for a national park quietly disappeared. Although paleontological areas had secured a place among federal reservations by this time (presidential proclamations under the Antiquities Act created Petrified Forest National Monument in 1906 and Dinosaur National Monument in 1915), there seemed to be little political interest for a park in the John Day Fossil Beds. What little local support the proposal could generate was more than offset by the fact that very few people had ever been to the upper basin. Without a rail line or roads suitable for automobiles, no park proposal could succeed in this remote and sparsely populated region.

Access to the upper John Day Basin

Grant and Wheeler counties remained comparatively isolated from the rest of Oregon until the 1920s. Construction of highways financed by state and county taxes linked residents of the upper basin to the outside and eventually allowed development of recreational amenities such as state parks. Even so, better roads did not bring more permanent residents (see Table 1) nor did the highways become much more than corridors for local traffic. Without them, however, it is doubtful that a national monument in the John Day Fossil Beds could have ever been established.

Ease of travel over mountainous topography was the primary concern in developing state and federal highways in the upper John Day Basin. Not surprisingly, their location often corresponds to the general location of earlier trail or wagon road segments. Many of them incorporated parts of aboriginal trails, a number of which provided access to the basin in the protohistoric period. [38]

Discovery of gold along Canyon Creek in 1862 quickly made an old route to The Dalles the main access for non-lndians to enter the upper basin. A series of trails went up the Deschutes drainage from The Dalles, joining the John Day's main stem between Pine Creek and Bridge Creek. Although rough and sometimes dangerous because of problems with the Northern Paiute, river and rail access at The Dalles made it the logical supply point for much of eastern Oregon.

State authorities contracted for the survey, mapping, and improvement of this series of trails in 1868. [39] In exchange for a sizeable grant of land, The Dalles-Canyon City Military Road Company agreed to build a road suitable for the transport of supplies from The Dalles to Boise. [40] (The name "military" during this period is a misnomer, because these roads actually represented federal financing of civilian developments on the frontier). In this case, work on The Dalles to Boise road lasted a year, having merely linked existing trails amid charges of fraud. [41]

Despite its often shoddy condition, the Dalles Military Wagon Road remained the main access to the upper John Day Basin for roughly 50 years. [42] Distance to markets shortened somewhat with construction of a railroad to Shaniko in 1900, followed by establishment of a terminus in Condon five years later, but few improvements to roads in the upper basin became evident until automobile use increased throughout eastern Oregon during the 1920s.

In 1914, the only road traversing either Wheeler or Grant counties that warranted inclusion on a map of state highways arrived in Fossil from the north. [43] It reached the Cant Ranch a year or so later, but road work had to be financed solely by the counties until 1917. [44] That year an act of the legislature created a system of roads supported by state funds which financed work on two highways in the upper basin. The John Day River Highway quickly became the most important route because it linked Grant and Wheeler counties with markets reached by utilizing the Columbia River. This road went from Biggs via Condon, Fossil, Spray, and Dayville to John Day. [45] At that point the route connected with the basin's other main road, the Pendleton-John Day Highway, which ran roughly north-south similar to what is presently US 395. [46]

Oregon's Market Road Act took effect in 1920 and had a profound impact on the road systems of Grant and Wheeler counties. Apportioned state and county taxes resulted in a number of road segments being built over the next two decades. Construction of a county road from Antelope to Mitchell, accessing the Painted Hills area, began in the 1921-22 biennium. [47] Another market road linking Clarno with Fossil appeared by 1926, though less than twelve years later it had been brought into the state system as highway 218. [48]

For the most part, placement of state and county roads in the upper basin had been set by 1930. Improvements followed, with the most ambitious being the rerouting of a road segment which followed part of The Dalles Military Wagon Road through Picture Gorge. [49] This section greatly aided east-west travel when completed in the early 1930s and later became part of US 26. [50]

Table 1. Census figures for Grant and Wheeler counties, 1890 - 1990.

| Grant Co. | John Day | Mt Vernon | Dayville | |

| 1890 | 5,0801 | 211 | -- | -- |

| 1900 | 5,948 | 282 | -- | -- |

| 1910 | 5,607 | 258 | -- | -- |

| 1920 | 5,496 | 321 | -- | 117 |

| 1930 | 5,940 | 432 | -- | 106 |

| 1940 | 6,380 | 708 | -- | 136 |

| 1950 | 8,329 | 1,597 | 451 | 286 |

| 1960 | 7,726 | 1,520 | 502 | 234 |

| 1970 | 6,996 | 1,566 | 423 | 197 |

| 1980 | 8,210 | 2,012 | 569 | 199 |

| 1990 | 7,853 | 1,836 | 538 | 144 |

1 Created from Wasco and Umatilla counties in 1864; areas transferred to Baker County in 1872, Harney County 1889, and Wheeler County 1899.

| Wheeler Co. | Mitchell | Fossil | |

| 1890 | 2,0312 | -- | 153 |

| 1900 | 2,443 | 135 | 288 |

| 1910 | 2,484 | 210 | 421 |

| 1920 | 2,791 | 224 | 519 |

| 1930 | 2,799 | 211 | 538 |

| 1940 | 2,974 | 219 | 532 |

| 1950 | 3,313 | 415 | 645 |

| 1960 | 2,722 | 236 | 672 |

| 1970 | 1,849 | 196 | 511 |

| 1980 | 1,513 | 183 | 535 |

| 1990 | 1,396 | 163 | 399 |

2 Created from Crook, Grant, and Gilliam counties in 1899. The figure for 1890 is an estimate.

Sources: Bureau of Municipal Research and Service, Population of Oregon Cities, Counties, and Metropolitan Areas, 1850 to 1957; University of Oregon Information Bulletin No. 106, April 1958; Oregon Blue Book, 1993, pp. 297-301.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002