|

John Day Fossil Beds

Floating in a Stream of Time An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

|

INTRODUCTION

|

No state is more richly endowed with the

records of earth history. No region in the world shows a more complete sequence of Tertiary populations, both plant and animal, than does the John Day Basin. |

| Ralph W. Chaney [1] |

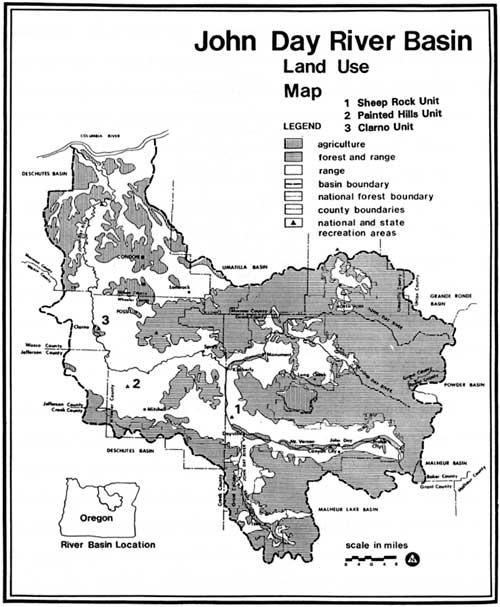

As one of the Columbia River's two main tributaries that drain north central Oregon, the John Day River flows westward from the Blue Mountains and then north through deeply dissected country. In draining some 8,000 square miles, the John Day Basin also exhibits impressive relief. Ranging from several hundred to more than two thousand feet above the streams, a number of ridges dominate this region. Valleys separating the ridges usually have sloping sides, such that their floors are rarely flat and usually somewhat narrow.

This drainage basin is classified as being within the Blue Mountains physiographic (landform) province of Oregon. [2] It is also a borderland between two larger provinces--the Columbia Plateau and the Basin and Range--which are part of a broader categorization scheme used for North America. The Columbia Plateau covers about 100,000 square miles to the north and west of the John Day Basin, and consists largely of flat or gently tilted basaltic flows. South and east of the basin is the Basin and Range Province which features a wide variety of rock types that are folded or faulted. Local separation of the two provinces is provided by the Strawberry and Aldrich mountains along the south side of the John Day River valley. [3]

Juniper and sage dominate the upland areas and characterize semi-arid conditions throughout the basin, where average annual precipitation is just 13 inches. [4] Some contrast to the sparse cover at lower elevations is, however, provided by the riparian areas that support comparatively lush vegetation, as well as by plant communities associated with pine forests above 5,000 feet in elevation. Most of the upper basin is too dry and rugged for extensive cultivation. Cropping is restricted to riverine areas that can be irrigated. Livestock grazing remains the basin's main industry, with human settlement sparse compared to more temperate parts of Oregon.

As representative of the wider basin, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument consists of 14,400 acres in three noncontiguous units. Sheep Rock is the largest unit, located a few miles northwest of Dayville in Grant County. The next biggest unit is Painted Hills, lying 10 miles northwest of Mitchell in adjacent Wheeler County. Also in Wheeler County is the smallest unit, Clarno, roughly 20 miles southwest of Fossil. An administrative headquarters is located at the park's main visitor contact point, that being the Cant Ranch in the Sheep Rock Unit.

|

| (derived from map in USDI-NPS, Final Wild and Scenic River Study, John Day River, 1979) |

Paleontological significance

Like a window cut through lava flows and underlying strata, so have water and time worked to strip away the upper John Day Basin's basalt cap. What at erosion has exposed there is representative of a much larger region, one where tremendous outpourings of lava in the distant past covered much of what is now the Pacific Northwest. An unusually coherent geological record spanning some 40 million years can thus be seen rather easily, though its size and complexity still has much to offer science after more than a century of study.

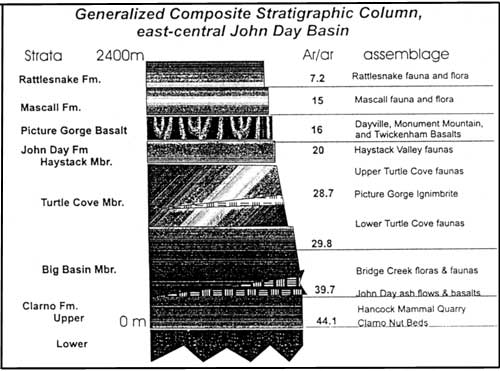

The upper John Day Basin provides evidence of evolutionary changes taking place during the Cenozoic Era, some 65 million years ago to the present. This era is divided into two periods, the Tertiary and Quaternary, which are further separated into epochs. The Tertiary Period consisted of five epochs: Paleocene (65 million years ago to 55 mya), Eocene (55 mya to 38 mya), Oligocene (38 mya to 25 mya), Miocene (25 mya to 5 mya), and Pliocene (5 mya to 2 mya). These preceded the Pleistocene (2 mya to 10,000 years ago) and Holocene (10,000 years ago to present) epochs of the Quaternary Period.

|

| Figure 1. Relation of strata to fossil assemblages in areas near the monument. Ar/ar refers to the relative dates (in millions of years) assigned to formations and their main subdivisions, or members. Note the duration and (implied) complexity of the John Day formation in comparison to others. (from Theodore Fremd, et al., John Day Basin Paleontology Field Trip Guide and Road Log, 1994) |

|

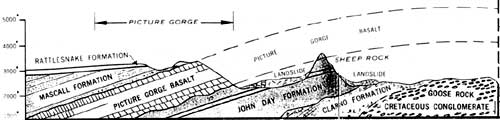

| Figure 2. Simplified crossection of an area in the Sheep Rock Unit, as seen from south of Picture Gorge. (from Thomas P. Thayer, The Geologic Setting of the John Day Country, 1969) |

To tie the geologic time scale with local layers of rock (called beds), similar strata are grouped into a more conspicuous unit known as a formation. Comparisons with strata elsewhere allow for correlation of these formations with a place on the geologic time scale. A sequence of formations can be correlated with Tertiary epochs in the upper John Day Basin, thereby allowing for study of evolutionary change over a long period with fossilized evidence. Furthest back in time of these formations is the Clarno (Eocene), followed by the colorful John Day (Oligocene), Picture Gorge Basalt (Upper Miocene), Mascall (Middle Miocene), and the Rattlesnake (Pliocene). Except for the Picture Gorge Basalt (which is part of the Columbia River Basalt that covers a much larger area), each of these formations contains fossils. All of them are clearly represented within the monument's boundaries, a highly unusual occurrence for a relatively small area.

Magnificent combinations of quality and diversity in the fossils, coupled with the length of time represented are the characteristics that make the John Day Basin internationally significant. [5] Vertebrate faunas in the Clarno, Painted Hills, and Sheep Rock units lie in close proximity to associated volcanic ash layers, magnetically altered rocks, polynomorphs, and floras. These associations span 40 million years of environmental change and allow comparison of the John Day fossil populations with those recovered from sediments of similar age throughout the world. The collective aim among paleontologists in doing this is, of course, to find global patterns of terrestrial floral adaptation and evolution of faunas. [6]

Popular recognition of the John Day Basin's importance to paleontology has been evident throughout the 20th century. Writing in 1901, John C. Merriam described its significance to readers of one national magazine:

"Although there are other geological sections, particularly in the Western United States, which furnish as remarkable [a] history...there are probably none in which the relations of the various chapters [of geological time] to each other are more evident than they are in the record inscribed on the walls of the John Day canyon. The deciphering of the geologic story of most regions is accomplished through the enthusiastic labors, over wide areas, of men taught to see things which escape the notice of untrained observers. The John Day section tells its story so plainly that to one who sees the record a comprehension of its meaning is unavoidable. " [7]

Over sixty years later, paleontologist J. Arnold Shotwell summarized the basin's importance in a report to the National Park Service (NPS) which supported establishment of a national monument:

" There is no question of the national or international significance of the John Day Basin. It has been clear for one hundred years. Neither is there any question of the clarity of the story to be seen by the visitor, [as] this is its chief value... Other areas now part of the National Park Service; Dinosaur, Agate Springs, Badlands and Flourisant, all deal with single chapters or some unique aspect of single chapters in the history of life. The John Day Basin offers an entire book!" [8]

The monument's significance to paleontology as a field of study has also been enhanced by the opportunity to interpret ongoing excavation and preparation of fossils by park staff. These demonstrations are in keeping with the reasons behind transfer of three state parks which formed the basis for this national monument. State park officials recognized the upper John Day Basin's paleontological significance, but did not possess sufficient means to convey its importance and foster public appreciation of why fossil resources warrant protection.

Other resource values

The monument contains regionally representative natural and cultural landscapes, as well as examples of geological processes that have and continue to shape the Pacific Northwest. [9] Some of its more recent (neontological) values are significant at the regional and local levels. [10] The John Day River, for example, is regionally significant as a recreational resource. A large portion of the drainage (including a part close to the Clarno Unit) has been designated as a federal Wild and Scenic River, as well as a state scenic waterway. [11]

Locally significant natural resources within the monument's boundaries include representative fauna such as raptors, coyotes, deer, and native fish. Lands embraced by the Congressionally-authorized boundaries may also act as refugia for sensitive or representative flora. As a mosaic of pastoral and comparatively undisturbed landscapes, the monument has been a staging ground for ongoing natural resource management programs which include riparian restoration efforts and a prescribed fire program. Two localities encompassing some 600 acres in the Sheep Rock Unit have been identified as possible research natural areas, but this nomination has not yet resulted in formal designation. [12]

At least one pictograph located in the monument's Sheep Rock Unit has continuing ethnographic significance to members of the Wasco and other Indian tribes. No formal assessment of these features has been made though the need for study has been identified. [13] The extent and significance of other prehistoric cultural resources within the boundaries of the monument, such as archeological sites, are still largely unknown.

The National Park Service has made some efforts to document the monument's historic resources, most notably at the locally significant Cant Ranch complex, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. [14] In addition, the Kam Wah Chung Museum, administered by the municipality of John Day and on the National Register, has been periodically suggested as an affiliated site. This museum is at least regionally significant, and awaits formal evaluation as a National Historic Landmark because of its exceptional ability to convey the Chinese role on the western American mining frontier. [15]

Purpose of the park

According to the National Park Service's strategic plan, the purpose of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is:

To protect the paleontological resources of the John Day Basin and provide for, and promote, the scientific and public understanding of those resources. [16]

This statement comes from the NPS planning process, not legislation, because an omnibus bill signed by President Gerald Ford on October 26, 1974, only authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to acquire lands identified on a boundary map. The monument's establishment proceeded without a statutory statement of purpose because sponsors of the authorizing legislation intended that John Day Fossil Beds National Monument take form through the agency's planning process. Within the first year of assuming control, the NPS arrived at a relatively general statement of purpose for the park in 1976 and subsequently incorporated it in the monument's general management plan approved in 1979. This one read:

To identify, interpret, and protect the geologic, paleontological, natural, and cultural resources along the central and upper John Day River and to provide facilities that will promote and assist visitor recreational enjoyment and understanding of the same. [17]

By 1995, however, the NPS believed that the significance of the monument's fossil resources warranted making paleontological values officially preeminent. As they put it:

The John Day Basin contains one of the longest and most continuous records of evolutionary change and biotic relationships in the world; this outstanding fossil records heightens our understanding of the earth's history and its biological evolution. John Day Fossil Beds National Monument contains a concentration of localities that are a major part of that record. The John Day Basin is one of the few areas on the planet with numerous well preserved and ecologically diverse biotas, entombed in dateable volcanoclastics, spanning a long interval of dynamic paleoclimate changes. [18]

Scope and format of the narrative

This is the first administrative history prepared for John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. It is also one of the first administrative histories sponsored by the NPS for an area where fossils are the primary resource. Administrative histories are intended to provide present and future monument staff with pertinent background on how a park took form. They have two main components: 1) how the park came to be established; and 2) issues associated with subsequent administration and management. More exhaustive contextual treatment of the monument's human history is left for a historic resource study to address because that document should identify and evaluate properties eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

As background to the monument's establishment, the first chapter of this administrative history summarizes some defining patterns and events which predate state parks in the basin. This is followed by a chapter showing how the three state parks created a footprint through which eventual authorization of the monument became possible. What transpired as a result of the NPS planning process from 1967 to 1979 is described in the third and fourth chapters, while the last three chapters provide some detail on significant issues and thrusts in the monument's administration.

Chapter format in this administrative history is chronological, moving from somewhat broad to more specific treatment. Source citations appear as notes at the end of each chapter and should act as a guide to relevant correspondence, documents, and files. Copies of this material are, for the most part, housed as archives in the monument's museum collection.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/adhi/intro.htm

Last Updated: 30-Apr-2002