|

Joshua Tree

The Native American Ethnography and Ethnohistory of Joshua Tree National Park An Overview |

|

THE NATIVE AMERICANS OF

JOSHUA TREE NATIONAL PARK

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT STUDY

by Cultural Systems Research, Inc.

August 22, 2002

IV. THE SERRANO

A. Major Sources

Major sources on the ethnography of the Serrano include Lowell John Bean and Charles Smith's paper, "Serrano," in the Handbook of North American Indians, V. 8 in the Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8, California 1978; A. L. Kroeber's Handbook of the Indians of California 1925; William Duncan Strong's Aboriginal Society in Southern California 1929; Bean and Vane's "Persistence and Power: A Study of Native American Peoples in the Sonoran Desert and the Devers-Palo Verde High Voltage Transmission Line 1978"; Bean and Vane's "Native American Places in the San Bernardino Forest, San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, California" 1981; Ruth Benedict's A Brief Sketch of Serrano Culture 1924, and Serrano Tales 1926; Philip Drucker's Culture Element Distributions V: Southern California 1937; Edward W. Gifford's "Clans and Moieties in Southern California" 1918; the J. P. Harrington notes; and the C. Hart Merriam notes. The foregoing include some ethnohistory. Secondary sources on ethnohistory are Beattie and Beattie's Heritage of the Valley: San Bernardino's First Century (1951) and Paulina La Fuze's Saga of the San Bernardinos 1971. Some information given here is drawn from recent research by CSRI and others in the records of San Gabriel Mission. Some is also drawn from Bean's notes on his ethnographic research at Morongo Indian Reservation in the late 1950s and 1960s, which include information drawn from Sarah Martin and other knowledgeable Serranos.

B. Traditional Territory

The territorial claims of the different ethnic groups who occupied the Mojave and Colorado desert in traditional times in southern California overlap each other, and scholars' descriptions of group boundaries are each of them different. In fact, the boundaries appear to have changed from one time period to another; moreover, groups would sometimes share territory, or a group would invite its neighbors to share an abundant resource.

Boundaries at any one time may have been quite specific, even though they can no longer be delineated. Most southern California elders that Bean has interviewed have been rather specific about where clan territories were located. Boundary markers are commonly referred to i.e. that hill just north of such and such next to such and such as example. Within some areas there were places of common use that were well known to the people who used them, but little such information has survived. (See Francisco Patencio 1943).

1. Oral History. A version of the Serrano creation story told by elder Dorothy Ramon describes Mara as the first place the Serrano lived after they came to this world:

Indians apparently used to live somewhere else. They were living on some planet similar to this one. The Serrano Indians came to a new world. There were apparently too many people on the old planet (not the planet Earth). They were killing each other (due to overpopulation). They did not get along. Then their Lord brought them to a new world. Their Lord brought them. There were too many people: they did not fit any more on their home planet. This is why he brought them here, to settle here for good. This was to become the new planet. It was a very beautiful world. So, many of them left (with their leader). They all came. They apparently believed in their Lord. He did not force them. He even asked people whether they would move to the new planet. Some of them believed in Him. He apparently led them to this planet. They came here. From there He brought them to this planet. I don't know how many years it took Him to bring them here. Finally they got there. And they are still here today. The Serrano talk about this in their songs. The Serrano named this place when they came to this world.... The Serrano people lived here. Coming from that other planet they started over at Maara' (Twentynine Palms). They had been living on their lands for many years. This is in their songs (Ramon and Elliot 2000:7-9).

In a second narrative, Mrs. Ramon reiterated:

It's there. They call it 'Twentynine Palms' nowadays. That was their place of origin, the territory of the Mamaytam Serrano. There was nothing but Mamaytam living there. It was their home. There were different tribes. There were many different kinds. The Serrano territory was extensive. It ended at the Colorado River. Their territory extended over here on the other side. Today they call it 'San Bernardino'. It continued all the way through Los Angeles to the coast (where the oil wells are). That was the Serrano people's territory long ago. I don't know how wide it was. That's what they used to say and that's what I say now. That's the extent of it. That's what they used to say, and that's what I say. There were others living at the place known as Maarrênga' 'Twentynine Palms'. That was the place of origin of the Maarrênga 'yam Hiddith 'the Orthodox Serrano'. Then all the Serrano got scattered. There are different tribes. There are a number of tribes. Today I only know (the name of) some of their tribes. I still know that Twentynine Palms was the territory of the Mamaytam. There were also Muhatna 'yam Maarrêng 'yam living there. That was the tribe of my relative, of my father's father. They also had an extensive territory. It's going to be that way forever. No one is ever going to own it. That land belongs to our Lord. It is not our property. That is all.

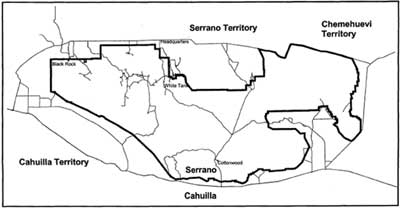

2. Claims Case Boundaries. Here we shall use the descriptions agreed to by the tribes themselves in suing for the reimbursement by the United States for depriving them of their traditional territory in the Claims Cases of the 1950s, even though these descriptions were and still are controversial.

In the Claims Case, the Serrano claimed the following:

Beginning at a point approximately 5 miles East of the City of Redlands; thence Northwesterly in an irregular line to a point in the approximate area of the San Gabriel Range which is due North of Mt. San Antonio; thence Easterly in an irregular line along the San Gabriel Range to Cajon Pass; thence Northeasterly in an irregular line approximately 8 miles; thence Northeasterly in an irregular line to a point approximately 3 miles Northeast of the town of Ludlow; thence Southeasterly in an irregular line to a point approximately 1 mile Southwest of the town of Cadiz; thence Southeasterly in an irregular line to a point in the approximate area of the Big Maria Mountains, approximately 12 miles West of the Colorado River; thence Southerly parallel with and approximately 12 miles Westerly of the Colorado River Westerly in an irregular line to a point due West of Blythe; thence Westerly in an irregular line to the approximate area of the present Hayfield Reservoir on the Colorado River Aqueduct; thence Westerly in an irregular line following the line of said Aqueduct to a point approximately due North from San Jacinto Peak; thence South in an irregular line to the approximate area of San Jacinto Peak; thence Southeasterly in an irregular line to the approximate area of Lookout Mountain; thence Westerly in an irregular line to the approximate area of Coahuilla Mountain; thence Northwest in an irregular line to a point which is approximately 12 miles southwest from the point of beginning; thence Northeast in an irregular line approximately 12 miles to the point of beginning (U.S. Court of Claims 1950-1960: Docket No. 80).

The Maringa (Mariña) Serrano, one of the most visible of Serrano groups in the historical period, occupied the south easternmost reaches of this territory, and were the most important Serrano clan, at least in the 19th century, after many of the Serranos who lived nearer the coast were taken into Mission San Gabriel in 1811. After that, the remaining Serranos moved southeastward to escape the Mission system. The Serrano at Mara were members of this clan, probably a lineage thereof. Other members of the Maringa clan in the mid-nineteenth century lived at Yamisevul, also known as Maringa', on Mission Creek, and eventually joined Cahuilla relatives on the Potrero (on Section 36 of T 2 S, R 1 E, SBM, where the waters of Potrero Creek were used to irrigate fields.

From Mara Oasis, the Maringa probably traveled seasonally to harvest plants and to hunt over the vast ranges of the Mojave and Colorado deserts to the east and southeast, but the northeastern part of the territory described in the Claims Case was probably the territory of the Vanyume, a group encountered by Garcés in 1771, and after that not known to have been encountered by those passing through (Galvin 1967; Kroeber 1925:614).

Joshua Tree National Park

Map 1. Tribal Boundaries, Claims Case

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

C. Subsistence Resources

1. Plant Resources. The use of plants by the Serrano is covered in Bean and Vane's ethnobotany of the park, which remains to be published. Bean and Saubel's Temelpakh (1972), which pertains to the ethnobotany of the Cahuilla contains much information applicable to the Serrano as well. Lawlor's dissertation on plant use in the Mojave Desert (1995) also contains pertinent information. None of these sources, however, touches as well on the meaning of plants to the Serrano as does Dorothy Ramon:

Long ago when the world began there were many Indian peoples here on earth. Their Lord was living here, with them, he was alive, not dead. He was like us, alive here. And he would speak to them. He would explain to the people about how to live, about how to get along here on earth. And there were lots of people. Perhaps different tribes. Our Lord came to them. He asked them whether they would allow themselves to be transformed to make medicine, so that medicinal plants would grow. They were to become medicinal herbs. Only those that believed were transformed. And so many plants exist now on Earth. 'Herbs', as the whites call them, grow on the earth. They were to become the Indian's medicine.

They (the Indians) would treat themselves with them (herbs), before their little brothers and sisters arrived (little brothers and sisters' is a euphemism for 'white people'). They (white people) weren't there yet. They had not been made yet, they were not here yet. He (our Lord) told the Indians about this long ago.

The Indians healed themselves with them (herbs). All the shamans knew where their medicine and food grew. Everything (we need) is available on Earth, in the hills, the song says. It grows. When it would rain regularly, it was nice. Everything that He created would grow. The Indians used to have lots of food long ago. They could also cure themselves with the same plants today. They (the first people) all transformed themselves. All those things grow on earth. And they would see them (those medicinal plants). Different kinds of medicinal and edible plants grew there long ago as well. Such things no longer exist, I think, who knows why? No one eats them nowadays. Eat different food nowadays. Some new kind of food. Now it has come out (this new kind of food). But long ago this was their food. People would always pick it (fruit) in the hills when it ripened. The women would always go pick those things. There was always food for them to eat. In the winter they would eat all kinds of things which they had dried. They would put food away. In the winter they would eat all kinds of things which they had dried. They would put food away for that purpose. They would store it away, they used to say. The same was true of medicine. The shaman knew where it grew, certain kinds. He would go and gather them in order to treat illnesses. He would treat people with them. He would cure a sick person with them (those herbs). There were a lot of medicines like that. Those white people refer to them as herbs. Some don't believe in that. But they (herbs) are beneficial. Some people do not believe in that (Ramon and Elliot 2000:357-359).

2. Animal Resources. The use of animal food in the area now included in Joshua Tree National Park is to be covered in a proposed ethnozoology by Bean and Vane. Information on such use is scattered in the various ethnographies mentioned above under "Sources." Dorothy Ramon has provided information about how the Serrano traditionally went about procuring and using animals for food, and how they regarded the animals. For them, animals, like plants, are people who have let themselves be transformed. Ramon tells the story of the origin of deer in the following:

Back in the beginning of time the Lord was living here with all the people. He was the one who asked the people whether they would turn into deer. He wanted to transform them. And they obeyed Him and were transformed. And so they were transformed. That's what He (their Lord) said. And so the deer would sing. And then the people would dance the deer dance. They would sing the deer songs. It (the song) tells about what they did, about how they were transformed. Some of them cried. Some of those animals were already transforming themselves. That is how He (the Lord) wanted it. And so they were transformed. They believed, that's why. And so they were all transformed. And so they sing to those deer who had transformed themselves. Their bodies were already completely transformed. But they still felt at home here. They were still behaving like human beings. But they had already been transformed into deer. And so they cried. They wanted to live in their homes, like human beings. There was one who kept circling about. He was looking inside, inside the (ceremonial) house. It says, that's what the song says, that he (the deer) is peaking inside and circling about. He kept peaking inside. He was looking inside the house. Some of those who had already been transformed were already wandering about outside. They had to go off somewhere else. And they climbed up into the hills. Those animals who had been transformed were destined to live in the hills forever. But they still did not know how to walk on their (newly transformed) feet. They already had hooves and were slipping along. They were not used to their (new) hooves yet. They already had hooves. That's what they did (Ramon and Elliot 2000:571-572).

Small game animals like rabbits were an important part of the Serrano diet, but there were rules about hunting them. For example, neither young hunters nor their parents could eat such animals: Ramon tells of her young brother's hunting:

Long ago I had an older brother ... my father taught him how to hunt. And he would always hunt. He would always hunt jackrabbits. When I was still small I would go around with my older brother. He had a lot of guns. My father bought them for him. He had different kinds of guns. We had them. We would walk about outside. We would hunt. But I never shot any rabbits. But he (my brother) would kill all kinds of jackrabbits and cottontailes. When he would kill one ... then we'd go home and .... But my family, my mother and father, would not eat the game that my older brother had killed, those rabbits. Long ago that was what the Indians did. My older brother was still young (under age). They did not eat the game he killed. I would eat it by myself. And so we would kill one. Then I would eat it by myself.

No one else would eat it. He himself would not eat the game he killed either. He was not old enough to eat his own game, they said. It was the same with my father and mother. They would not eat-it. They did not eat the game killed by boys. But I ... he would give it to me. I ate it by myself. That's what they used to do long ago. And I learned to hunt a little by following him around. You could get used to it and then you could always shoot things, and kill whatever you want. It was not right for a woman. That's what some people said. But some women can shoot anything. They don't care. They get used to it. They can do anything. They could kill anything. They don't care, they say. I wasn't interested. I didn't know how. At the time I too was just a little girl. And that's how it was long ago, as I said. My older brother was a hunter like my father. He taught him how to hunt all the time. He died when he was still young. He passed away (when he was 15). That's all (Ramon and Elliot 2000:483-485).

Large game animals were killed only after the appropriate rituals. As Ramon tells it:

Those par'cam hunters were trained to do that. They would appoint them like that. The paxa 'yam ('ceremonial officials') would first teach them how to hunt. When there was some religious celebration all the par 'cam hunters would go hunting. They would kill a deer or something. They would bring their kill to the ceremonial house. Some of them would sing (prayers) over it (the killed game). They would sing all night. Those people would sing about bighorn sheep long ago. They would butcher it. They would eat it. They did not just eat a bighorn sheep any old way. Long ago I saw them doing that, when they were going to hold a feast. First they would pray over it. They would sing over it. They would do all kinds of things. They would dance (round 2:30 or 3:00 a.m.). They would continue their ceremonies through to dawn. That's how they were. That's what people did long ago. I saw them with my own eyes (Ramon and Elliot 2000:485-487).

D. Material Culture, Technology

The Serranos acquired the many species of large and small animals available in the area with throwing sticks, various types of traps, nets and snares, arrows, and sinew-backed bows. They also used poison. Baskets were the containers of choice for gathering plant products. These were used not only for transporting the plant products, but also for winnowing, cooking, and storing. Cooking in baskets was carried out by placing hot stones in food held in tightly woven baskets. While the adults and older children were carrying out their various tasks, babies lay or sat in baskets, sometimes carried by the mother, sometimes placed on the ground or a convenient rock. Although one might assume that pottery would have less use than basketry in a desert environment, a considerable number of pottery vessels have been found in the area, showing that pots were used for carrying and storage. Pottery vessels were useful for carrying water, the slight evaporation keeping the remaining water cool. Pottery was often used to cache precious or sacred property in caves when necessary.

The mortars and pestles, manos and metates, and hammerstones used for pounding, and for grinding food were made by grinding the quartz manzonite and other rocks that were plentiful in most parts of the area. Flaked stone tools served a variety of other purposes. They included fire drills, awls, arrow-straighteners, flint knives, and scrapers. Horn and bone were used for spoons and stirrers.

The Serranos kept warm in winter by wearing clothing made of animal hides, and sleeping under woven rabbitskin blankets. For ceremonial events, they used garments made or decorated with feathers, and made rattles made of turtle and tortoise shells, deer-hooves, rattlesnake rattles, and various cocoons. Wood rasps, bone whistles, bull-roarers, and flutes were used to make music to accompany the many songs and dances used in ceremonies.

Baskets were not the only thing they wove. Using fibers from yucca, agave, and other plants, they wove bags, storage pouches, cording, mats, and nets (Drucker 1937; Bean 1962-1972; Bean and Smith 1978).

Most Serrano houses were circular domes that had a central fire pit. The homes of several families tended to be clustered in small settlements, and included not only the houses, but also basketry granaries for storage of food, sweathouses, and often a ceremonial house. They were placed near springs or other water sources, and as near as possible to other resources (Bean and Smith 1978).

E. Trade, Exchange, Storage

The Serrano stored such foodstuffs as acorns, mesquite beans, screw beans, and other storable foods in large basketry containers sometimes mounted on poles out of doors. Other foodstuffs, such as dried meats, small seeds, and fruit, were stored in basket or ceramic containers inside their houses, along with other supplies (Bean and Smith 1978).

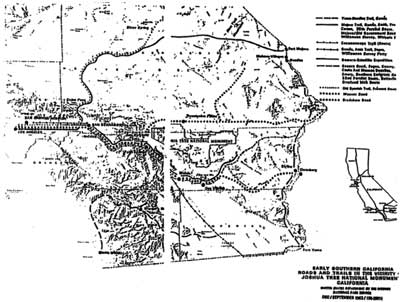

Their principal trading partners were the Mojave to the east and the Gabrielino to the west, but they also traded with their close neighbors, the Cahuillas and Chemehuevi. They constituted, in fact, a major nexus in a trade and exchange system that brought goods (and later, horses) from the Southwest to the coast. The finding of obsidian coming from long distance, i.e. Obsidian Butte and the coastal volcanic field (Warren and Schneider 2001: MS-ii) shows that people living in area now set aside as the Joshua Tree National Park had both direct and indirect contact with peoples many hundreds of miles away, both in the southwest and northeast directions. They would have gone from the coast to inland Arizona, probably to Nevada, and north of the Mojave Desert, as well.

Material goods, shells, sacred regalia (feathers and the like), were favored materials (Bean and Vane 1978).

Trade and exchange occurred informally between family members, at trade feasts, social events, and ceremonial occasions (Bean field notes 1958-1970).

F. Social structure

The territory of the Serrano, a non-political ethnic nationality (Kroeber 1925:615-616), was divided among a number of politically independent groups, which were patrilineal, patrilocal corporate clans, each of whom belonged to either of two exogamous moieties, Coyote or Wildcat. Each clan was composed of lineage sub-units, each of which had its own territorial base within the clan territory, the remainder of which was shared. It was, furthermore, forbidden that individuals marry anyone related to them within five generations. It follows that marriages across clan boundaries were necessary. The clans were divided into autonomous land-holding lineages. Each of these lineages had a chief, or ki'ka, with religious and political functions. His office was in general hereditary. His principal assistant was the paha, who assisted him in ceremonial, political, and economic affairs.

Throughout the year, individuals or groups left their communities as necessary to hunt, collect and gather, and process foods. They also collected whatever materials the environment or other groups could provide that were deemed necessary or useful (Bean field notes 1958-1970).

Joshua Tree National Park

Map 2. Early Routes Across the Desert

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

G. Religion, World View

Serrano world view, like its culture in general, is less well known than that of some of their neighbors, such as the Cahuilla. This lack is due to several circumstances. In part, it is because so large a proportion of the Serrano people were brought into San Gabriel Mission before or in 1811, after the failure of an attack on the mission. Disease subsequently further decimated the population. When scholars began to study Serrano culture, few remembered it as it was before the arrival of Europeans. It is known, however, that to the Serrano, as to other Native Americans, the plants, animals, and even rocks in the environment are sentient beings. As noted above, it is believed that they derive from human beings at creation time who were willing to be transformed into other beings.

The Serrano creation epic tells of two brothers in a story that is very similar to that of the Cahuilla and Luiseno. It tells of twin brothers, Pakrokitat and Kukitat, at the dawn of time. Pakrokitat created human beings and three beautiful goddesses on an island called Payait, to which he fled after disagreeing with Kukitat as to whether human beings should die, as the latter thought they should. Human beings divided into groups, and the groups warred with each other until it was decided that Kukitat, having done poorly by them, should be put to death. Kukitat's final illness, after Frog swallowed his excretions and thereby poisoned him, Coyote's theft of his heart, his death, and his subsequent cremation took place on the shores of Baldwin Lake in the San Bernardino Mountains. In a fight that erupted after the death, all the Mariña Serrano were killed except one man, from whose posthumous son all subsequent Mariña Serranos are descended2 (Kroeber 1925:619; Harrington Serrano notes; Bean and Vane 1981:158).

2A common theme in southern California oral literature is that of a catastrophe, caused by oversight, deception, or accident, in which only a single male child survives, and becomes the progenitor of a new group from which subsequent people descend.

The story of Kukitat's death and cremation was sung until the 1960s at the Serrano's annual Mourning Ceremony, at which the Mariña as the oldest clan took precedence (Strong 1929:34; Bean field notes 1975).

In the earlier part of the 20th century, the Serrano and Cahuilla often joined forces to conduct their traditional ceremonies. When W. D. Strong was doing his field work in the 1920s, the Serrano Mariña and Aturaviatum and the Wanikiktum and Kauisiktum Cahuilla conducted their ceremonies jointly, being the last active religious organizations of their groups. It was customary for each group to hold its annual mourning ceremony once every two years, with the other three in attendance (Strong 1929:14-15).

Ramon speaks of an earlier time, when the ceremonial leader of the Serranos at Twentynine Palms, having no ceremonial house, came to Mission Creek to hold a feast:

Long ago they held a feast in the home of our ancestor who has since passed away. He was from Twentynine Palms. But there was no ceremonial house there (at Twentynine Palms). He moved here from there. They were having a feast somewhere ... (at) Mission Creek... .

He built a ceremonial house. I was still small at the time (around five or six). I don't know how old I was. I must have been about four, five, or six, I am not sure. But I was a little bit aware of my surroundings. And so they built it. I saw those men who were building the ceremonial house. I would be asleep sometimes. I didn't see everything (while asleep). Sometimes I would be awake. There were very many men who would dance. I think it was morning. I am not sure. I don't know what they were dancing. I think they must have been dancing the deer dance. That's all I know, and so that's what I'm talking about. At the time I was very little (Ramon and Elliot 2000:259).

H. History

1. Mission Period. The Serrano were a fairly numerous people when the Spanish arrived in 1769, but beginning about 1790, the westernmost of them began to be drawn into Mission San Gabriel. After an attempted Indian revolt in 1810, most of those in the San Bernardino Mountains and the western Mojave Desert were brought into the mission, some of them forcibly. Those in the easternmost deserts beyond the San Bernardino Mountains and Little San Bernardino Mountains were beyond the reach of the mission, but probably absorbed a number of those who fled the missions.

We have presented the oral history account that tells us that the Maringo Serrano were the original inhabitants of the village of Mara at the oasis of Twentynine Palms. It was probably early ethnographers who made the first written record that Mara near the headquarters of present-day Joshua Tree National Park was originally a Maringa Serrano village, but we have not learned from either written or oral literature how early this settlement may have been established-a question whose answer may lie in archaeological sites not yet examined. It is also not clear whether this was the main or "first" Maringa lineage settlement at one time, as the oral literature attests, or merely one of several places in a large area they used and occupied; however, the fact that it was near a major source of water with a valuable complex of biotic resources for food and manufactures argue for its use as a living place for Native Americans for a very long time.

2. American Period. It has been suggested that the Serrano left the area in the early 1860s when a smallpox epidemic struck the Indians of southern California, even though the isolation of the area should have protected them. Their fate may instead be described by Ramon, whose account derived from Serrano oral history tells a story that we have not found in any other published source:

Long ago the Serrano lived at Twentynine Palms. Long ago some white people killed them there. They (whites) got there. They hunted them. They did all kinds of things to them. They killed a great many of them. They were lost. There used to be a lot of Serrano living there. They (the survivors) were afraid. Some of them apparently moved somewhere else. Many of them apparently moved elsewhere to other tribes. They lived here (at Morongo), after being run off of their own land, I guess. Apparently there was no one living at Twentynine Palms long ago (after the massacre) because they were afraid to live there. They were afraid, they apparently did not want to live there. This is because they (the whites) had massacred them (the Serrano) like that. My grandfather (mother's father) was a ceremonial leader there. He concluded, "It looks like they are going to get rid of all of us here." That is what he thought. He came here (to Morongo) to ask (for permission to stay). He apparently asked if he could settle here (on the Morongo Reservation). And the people here, the Wanakik Pass Cahuilla, said, "Alright" (Ramon and Elliott 2000).

Inasmuch as Ramon was in her 80s when she told this story, her grandfather might well have been at Twentynine Palms in the early 1860s.

The Maringa Serrano were living at yumisevul in the Mission Creek area, presumably before the 1870s (Strong 1929:11). According to some Cahuilla traditions, they replaced Cahuillas who had been living there. They intermarried with the Gabriel family (the ceremonial leaders of the Wanikik Cahuilla), and had moved to the Potrero, or Malki, by the 1870s. Here John Morongo, a leader of the group, played a leading role in the affairs of the newly established Morongo Indian Reservation. It is logical to assume that the Serrano left Mara because of pressure from settlers and miners, and better economic opportunities elsewhere. Mission Creek, and the Potrero, on what is now Morongo Indian Reservation, where many of them settled, were richer in plant and animal resources, being not so far into the desert, and closer to jobs.

3. Present Day Serrano. Morongo Indian Reservation probably has more Serranos than any other reservation, but since many of its members are mixed Cahuilla and Serrano, it is difficult to establish whether the majority are Serrano or Cahuilla. San Manuel Indian Reservation appears to be exclusively Serrano, but it is a very small reservation, and home to a relatively small number of Serranos. The recent success of casinos at both reservations has made them prosperous reservations, whose people are increasingly interested in their culture and history, and are generously devoting resources to recovering the available pertinent information.

jotr/bean-vane/history4.htm

Last Updated: 02-Aug-2004