|

Joshua Tree

The Native American Ethnography and Ethnohistory of Joshua Tree National Park An Overview |

|

THE NATIVE AMERICANS OF

JOSHUA TREE NATIONAL PARK

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT STUDY

by Cultural Systems Research, Inc.

August 22, 2002

V. CHEMEHUEVI

A. Major Sources

Major sources on Chemehuevi ethnography and ethnohistory include Fowler and Fowler's Anthropology of the Numa: John Wesley Powell 's Manuscripts on the Numic Peoples of Western North America, 1868-1880 (1971); Kelly's "Southern Paiute Bands" (1934); Laird's The Chemehuevis (1976), and Mirror and Pattern: George Laird 's World of Chemehuevi Mythology (1984); A. L. Kroeber's "The Chemehuevi" in his Handbook of the Indians of California (1925); Chester King and Dennis Casebier's Background to Historic and Prehistoric Resources of the East Mojave Desert Region (1976); George Roth's "Incorporation and Changes in Ethnic Structure: The Chemehuevi Indians" (1976); Clifford E. Trafzer, Luke Madrigal, and Anthony Madrigal's Chemehuevi People of the Coachella Valley (1997); Amiel Weeks Whipple's Reports of the Most Practical and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean (1856); Baldwin Mollhausen's Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to the Coasts of the Pacific (1858); Dennis Casebier's Camp Rock Spring, California (1973); and Robert M. Laidlaw's Desert-wide Ethnographic Overview (1979). Government documents generated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and its predecessor, the Office of Indian Affairs, provide information about the Chemehuevi at the Twentynine Palms Indian Reservation, the Chemehuevi Indian Reservation, and the various Coachella Valley reservations where people with Chemehuevi ancestors now live.

B. Traditional Territory

In the Claims Case, in which, it should be noted, anthropologists such as A. L. Kroeber and Ralph Beals served as expert witnesses on their behalf, the Chemehuevi claimed the following as theirs before the arrival of the Spanish:

Beginning at a point in southern Nevada six miles west of a place on the Colorado River where said river encloses a small island in the latitude of Mount Davis (this starting point being east northeast from Searchlight and slightly east of south from Nelson); thence southerly to the summit of the mountain called Avi-Kwame by the Mohave and Yuman tribes, and Agai by the Chemehuevi Indians; thence southerly along the crest of the Dead Mountain-Manchester Mountain range in California, generally paralleling the Colorado River; thence southerly along the ridge of the Sacramento Mountains to the middle of Township 23E, 7N; thence southeast to the middle of Township 24E, 6N, along a line dividing the Chemehuevi Mountains; thence east across the Colorado River at a place known as Blankenship Bend; thence north of east in the State of Arizona to the Mohave Mountains; thence south southeast over a peak known as Akoka-Numi, for approximately 12 miles; then west southwest across the Colorado River to the southwestern corner of Township 26E, 4N, in the State of California; thence southwest along a line paralleling the Colorado River to the summit of the Whipple Mountains; thence southwest to the summit of the West Riverside Mountains; thence southerly to the beginning of a gap in the Big Maria Mountains separating the main eastern mass of these mountains from a spur projecting westward toward the Little Maria Mountains; thence northwest to the crest of the Iron Mountains; thence northwest on a line between the Bristol Mountains and the Cady Mountains; thence north, northeast, east, and again north, on a curving line passing north of the Bristol Mountains and first south and then east of Soda Lake to a point about the middle of Devil's Playground at the western edge of township 10W, 13N; thence east northeasterly through Townships 10 to 14E, 13N, to Cima; thence northeast to a place on the California-Nevada State Line about three miles east of Nipton; thence easterly to the point and place of beginning (U.S. Court of Claims 1950-1960: Docket No. 351).

The Chemehuevi have for a long time lived in close conjunction with the Mojave, usually, but not always, on friendly terms. They ranged from the river to the San Bernardino Mountains, which were, according to Laird (1976:7) a "familiar hunting ground, well-sprinkled with Chemehuevi place names."

C. Subsistence Resources

The use of plants by the Chemehuevi is covered in Bean and Vane's ethnobotany of the park, which remains to be published. Bean and Saubel's Temelpakh, which pertains to the ethnobotany of the Cahuilla contains much information applicable to the Chemehuevi, and Elizabeth J. Lawlor's dissertation on plant use in the Mojave Desert (1995) also contains pertinent information. It is planned that animal resources will be described in a forthcoming ethnozoology.

D. Material Culture, Technology

The material culture developed by the Chemehuevi is very much like that of their neighbors, the Mojave, Serrano, and Cahuilla. As is usually the case, apparent differences are in part due to the types of material that were available and in part to their preferences.

The Chemehuevi women were skilled basket makers, but made little pottery. Their coiled baskets resembled those of the San Joaquin Valley rather than those of southern California, often having constricted necks. Caps, triangular trays, and carrying baskets were diagonally twined. They usually painted designs on the baskets, rather than weaving them into the basket.

They made a self-bow shorter than that of the Mojave, with recurved ends, the back painted, and the middle wrapped. Arrows were often made of cane, and sometimes willow, with a foreshaft and a flint point. Houses were shelters against the wind and sun (Kroeber 1925:597-598; Laird 1976:5). The bow used in war was sinew-backed hickory, which was very hard to draw. It was short and powerful. Another kind of bow was made of the antler of the mule deer (Laird 1976:240).

Bows for hunting were made of sinew-backed willow. The adoption of the sinew-backed bow permitted the Chemehuevi to hunt big game, thus improving their supply of protein food (Laird 1976:5-6).

The principle material used for houses was brush. Of the four different kinds of houses they made, one was the flat or shade house, built for ceremonial occasions. A flat roof of brush was laid across four notched posts. Another roof that sloped to the ground on the west side was built above the flat roof to provide extra protection from the sun. In addition, a very large flat house was built to hold the goods brought to a Cry to be burned or given away (Laird 1976:42-43).

E. Trade, Exchange, Storage

The Chemehuevi often stored food, after drying or cooking it, in granaries or ceramic jars at their homes, or, on trips through the desert, by burying it in the ground or putting it in caves in pots or baskets. Edible seeds were often stored in baskets covered with potsherds and greasewood gum. The hearts of mescal and other plant resources were boiled and pounded into slabs for storage. Meat, and the pulps of melon and squashes were dried. The need for caches of food and other goods was sufficiently important that stealing food from someone else's cache was enough to bring on a war (Laird 1976:6). In fact, among most southern California Indians, food could be protected by "magical" means, i.e., by placing in the cave a notched stick, called by some a "spirit stick," which could cause harm to anyone who disturbed the cache.

The Chemehuevi "bought" eagles from other tribes, especially the Walapai, for the Mourning Ceremony (Laird 1976:42). Many valuable goods were exchanged at a Cry. Articles belonging to the deceased that the deceased had not seen might be given away. All other of the belongings of the deceased were burned, says Laird, "with the possible exception of the horse" (1976:43).

Cowrie shells from the seacoast were traded inland to the Chemehuevi for use in decorating women's clothing (Laird 1976:6).

F. Social structure

That the Chemehuevis had something that resembled a moiety system associated with the ownership of land in demonstrated in two hereditary songs, the Mountain Sheep Song and the Deer Song, each of which described trips through the mountains and valleys along the Colorado River. Those who had the right to sing the song had the right to hunt in the area and in that sense owned it. The songs were inherited patrilineally, but after the Euro-Americans came a man might inherit his song from his mother's father if his father were a non-Indian and thereby had no song, and, therefore, presumably no right to use the economic assets thereof.

Groups of Chemehuevis had a right to hunt in a Mountain Sheep area only if a man who was an owner of the Mountain Sheep Song was part of the group. The same was true of the Deer Song. The Mountain Sheep Song covered an area west of the Colorado River, and the Deer Song, east of the river. The Salt Song was associated with the Deer Song, and was often owned by those who owned the Deer Song, but it involved both sides of the river. Each song had subdivisions, and a subgroup might own only a subdivision of a song, and a specific version of it. A person was not to marry within the group that owned the same version (Laird 1976:3-19), a fact that gave the Chemehuevi something of an exogamous moiety system like that maintained by their western neighbors, the Serrano and the Cahuilla.

Only a person who owned a song could sing it ritually, but others could sing it in non-ritual contexts. There were other songs associated with hereditary hunting rights, but they each belonged to a group of related persons and were not subdivided (1976:18-19).

Laird maintains that the Chemehuevi were rather loosely matrilocal,3 with people being able to move from group to group as they needed to-a useful strategy in a desert habitat where the quantity of food resources was variable. A band consisting of two or three families traveled together and had a spokesman. It took its name from a place where its crops were planted, and to which it returned each year.

3They may have been bilateral bilocal, as other scholars maintain.

Each of the three main groups of Chemehuevi had High Chiefs who spoke the "Chief's Language" and had a duty "to set a good example and to teach his people a moral code, long since lost," and guided his people in peace. The High Chiefs and their relatives owned the Talking Song (also called the Crying Song), which was in the Chiefs' Language, and was sung only at funerals and Mourning Ceremonies (1976:24-29).

G. Religion

According to the creation story as told by George Laird, Ocean Woman, also known as Body Louse, created the earth by dropping a little mud into the ocean, where it floated. She kept spreading it out, and presently created Coyote from the mugre, or scrapings, from her crotch. He kept traveling to see how wide the earth was, and when it took all day to go and return to its edges, he told Ocean Woman it was large enough. She then created Wolf and Mountain Lion as brothers to Coyote, Wolf being the considered the oldest because Coyote had so little sense (Laird 1984:32-33).

Coyote and Ocean Woman, who had a toothed vagina, mated, after Coyote-by inserting the neckbone of a female mountain sheep into her vagina-made that possible, and created a basketful of children whom Coyote carried across the ocean. The basket was tied shut at the top, and Coyote was told not to open it until he got to his house. Once he got across the ocean, it was so heavy that he untied it, and the coastal Indians escaped. He tied it up again, and took it home, where Wolf opened it and released and brought to life the Chemehuevi, the Shoshoni, the Panamints, the Cahuilla, the Mojave, the Walapai, the Supai, the Quechan, the Maricopa, the Papago or Pima, and the Apache, naming them in the Chemehuevi language as they escaped. Those that were left were the Europeans. Wolf's use of the Chemehuevi language suggested a special relationship between Wolf and the Chemehuevi (Laird 1984:39-48).

Further Chemehuevi myths included various patterns for human behavior, and explained how the patterns came to be (Laird 1984).

H. History of the Chemehuevi

1. Early History. The Chemehuevi are the southernmost branch of the Southern Paiute people. According to Isabel Kelly's consultants, the Chemehuevis split from the Southern Paiutes in the Las Vegas area before the early 19th century, and moved toward what is now the Chemehuevi Valley and the area south of it on the Colorado River (Fowler and Fowler 1971:105; Kelly 1934). According to George Roth, the Chemehuevi and Southern Paiutes apparently moved into the Mojave Desert about 1500 A.D., replacing the Desert Mojave in the eastern Mojave Desert, and to some degree sharing the desert with them thereafter, the Mojave retaining the right to travel through it. There were separate Desert Mojave and Chemehuevi trails across the Mojave placed just far enough apart that those who used them would not encounter each other directly. Father Garcés recorded the presence of "Chemevet" near the Whipple Mountains near the Providence Mountains in 1776 (Roth 1976:81). The next mention of possible Chemehuevi in the literature is Jedediah Smith's account of coming across two "Paiute" lodges at a place in the Mojave River about eight miles west of Soda Lake in 1827 (Sullivan 1934:33). In the half century between the two sightings, the Franciscan missions had been founded along the coast, and runaways' from them must have visited the Chemehuevi villages, followed no doubt by Spanish soldiers in pursuit.

Trafzer, Madrigal, and Madrigal (1997) write that until the late 1820s some Chemehuevis have told them that Chemehuevis were living in the same villages as the Halchidhoma, the Yuman-speaking group who lived south of the Mojave on the Colorado River. At that time, Halchidhomas were driven from their homes by the Mojaves and Quechans. The Chemehuevi who shared a riverside village with the Halchidhomas some 15 miles south of Parker, Arizona, learned that the Mojaves were about to attack and warned the Halchidhomas. They themselves then moved to the western side of the River. After the war, they moved into some of the area once occupied by the Halchidhoma, and were tolerated there until the 1860s.

2. American Period. Inasmuch as the Twentynine Palms area was relatively isolated, we do not know whether Chemehuevis occupied any sites there before the later years of the 19th century. The kind of settlement that might have been found from time to time within the bounds of the park was probably similar to a site near Paiute Creek described by Whipple, who crossed the desert in 1856: "A little basin of rich soil still contains stubble of wheat and corn, raised by the Paiutes of the mountains. Rude huts, with rinds of melons and squashes scattered around, show the place to have been but recently deserted. Upon the rocks, blackened by volcanic heat, there are many Indian hieroglyphs" (1956). Heinrich Baldwin Mollhausen, who accompanied Whipple, wrote that the expedition found the shells of desert tortoises wherever there was water, indicating that the meat of the tortoise was an important part of the Indian diet in the desert (Mollhausen 1858).

In 1858, immigrants from the east trampled the Mojaves' fields, and cut down to make rafts the Mojaves' valued cottonwood trees. The trees were valued resources for the Mojaves, who used cottonwood lumber to build their homes, and the inside bark for making garments. Moreover, they provided shade for men and animals in the hot summers of the area. Alarmed and angered, the Mojaves attacked, killing one man, wounding 11 others, and killing most of the immigrants' cattle and horses. Hualapais and 7 rengegade Mojaves murdered all of another small immigrant party. This encounter led to the establishment of Fort Mojave at the Mojave villages and the subjugation of the Mojaves by the U. S. military.

During the hostilities, the Chemehuevi were allies of the Mojave, but, being extremely adaptable people, their style of resistance to the invaders was different. Unlike the Mojaves, they had adopted firearms, and they practiced a kind of guerilla warfare instead of the hand-to-hand combat favored by the Mojaves. The Chemehuevi killed an occasional immigrant, and raided the immigrant trains for livestock. Once Fort Mojave was established in the spring of 1859, the U. S. Army enrolled Mojaves in expeditions against the Chemehuevis and Paiutes.

In 1861, the beginning of the Civil War in the United States caused the Army to withdraw its troops from the Mojave Desert. About this time, a number of Euro-Americans found deposits of valuable minerals in the deserts of southeastern California, and established mines, a number of them in Chemehuevi territory, and hired Chemehuevis and Paiutes to work in them.

In 1864, after the town of Prescott was developed to be the capital of the new territory of Arizona, there was an urgent need for a mail service to California. One possible route through California lay through the Coachella Valley and eastward along the Bradshaw road to La Paz, Arizona. The other lay along the Mojave River between Mojave Valley and Cajon Pass to San Bernardino. The Project Area lay between these two routes, of which the northernmost was chosen. Once the route was established, there were a number of casualties from the Chemehuevis and Paiutes who occupied the desert, traveling from the site of one resource to that of another. The Indians became increasingly aggressive in the summer of 1866, when several isolated killings were followed by a battle at Camp Cady, an existing military outpost midway between Cajon Pass and the Colorado River, in which the Indians killed three soldiers and wounded two others without themselves suffering any casualties. After this, the U. S. Army established a military camp at Camp Rock Spring near the eastern border of California, and began accompanying each mail with three outriders. Eventually, there were military posts at Soda Springs, Marl Springs, and Pah-Ute (Paiute) Spring, as well. Because of the reports and letters written and received by men stationed at these military posts, we know that Chemehuevis and Paiutes traveled from place to place in the Mojave Desert, and from to time attacked the men who carried the mail. Late in 1867, Major William Redwood Price, at Fort Mojave, negotiated a treaty of peace with 60 "well-armed Pah-Ute warriors," and kept a number of hostages at the fort to ensure that the peace would be kept (Casebier 1973:60-64). At the other end of the Mojave trail, where Indians had burned and looted in the vicinity of Lake Arrowhead and Bear Valley, settlers organized a surprise attack on Indians assembled at Chimney Rock, overlooking Rabbit Lake. Warned of the impending attack, most of them fled into the desert, but the settlers pursued them for 32 days and many lost their lives. Price's treaty and the settlers' military actions brought peace to the Mojave Desert (Beattie and Beattie 1951:421).

Meantime, along the Colorado River, relationships between the Mojave and Chemehuevi deteriorated. For some years they had lived side by side along the river, each group practicing flood plain agriculture and maintaining amicable relationships, but in the 1860s expedition after expedition of immigrants from the United States came across the desert heading for California, and even ships came up the Colorado River. After minerals were discovered on the Arizona side of the river, miners from northern California who had participated in the campaign of genocide against the Indians there came to the southern mines, and brought their antagonism toward the Indians with them. In this increasingly hostile climate, Chemehuevis and Mojaves turned against each other. There were murders of Mojaves by Chemehuevis, and of Chemehuevis by Mojaves. The tension between the two groups escalated into war between 1864 and 1867. Many Chemehuevi thereupon fled into the Mojave Desert, to the Coachella Valley, and to Twentynine Palms (Kroeber and Kroeber 1973:33-46; Trafzer et al. 1997:62-67).

3. Chemehuevis at Twentynine Palms. Trafzer et al. note that Chemehuevis had lived at the oasis of Twentynine Palms many times before the 1860s, as had other Indian groups. "Serranos had previously inhabited the area in the 1850s and early 1860s, but when they returned to Twenty-nine Palms in 1867-1868, they found Chemehuevis living there (1997:67).

When Indian Agent George Dent of the Colorado River Indian Reservation tried in 1867 to get Chemehuevis to move to that reservation, the group that had settled at Twenty-nine Palms refused to go there, being unwilling to place themselves under the control of the government. They wished to preserve their language and religion and "maintain their sacred sites" (1997:69).

For some years, it was possible for the Chemehuevis to live in something close to their traditional way at Twenty-nine Palms, located as it was in a relatively isolated part of the desert. The water at the oasis permitted them to garden, and the surrounding area provided plant foods to gather and good hunting. As non-Indians moved into the area with their livestock, the animals depleted the plant resources provided by the area, which sustained both the Indians and the animals they hunted. Moreover, the invading whites with their guns depleted the animals the Indians depended on for meat. The Chemehuevis were eventually reduced to working for wages and buying processed foods, but the isolated location of Twenty-nine Palms made it difficult to earn enough for the level of subsistence that would maintain them. They began to die of malnutrition and white man's diseases, although their isolation kept them from contracting smallpox in the epidemic that raged through southern California in 1877 and 1878. The birth rate dropped as mothers became malnourished (Trafzer et al. 1997:69-74). When white families began to claim land in the Twentynine Palms area, they also claimed water rights at the oasis there. The situation became especially desperate for the Indians when the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, which had been granted alternate sections of land on either side of its route in the early 1870s, claimed the water at the oasis, and denied the Indians access to it (Trafzer et al. 1997:74).

4. The Establishment of the Reservation. The Chemehuevi at Twentynine Palms for many years were never mentioned in the reports of agents sent out by the United States government to visit the Indians of southern California, since they lived in an area between the routes usually used for travel and trade. Their neighbors to the west, on the other hand, were visited by a series of agents assigned to study the situation and report on what should be done about it. Everywhere settlers were squatting on the very spots where Indians had made their homes, near water and the plant and animal resources on which they lived. Various strategies for coping with the problem were suggested, but it was not until the mid-1870s that presidents, under pressure from Eastern reformers, began to set aside reservations on which Indians were invited to make their homes. Some fairly adequate reservations were established, but soon settlers began to complain about so much good land being set aside for people who were, in the opinion of the critics, unable to use it. Squatters began to move onto some of the best lands of the reservations. The fact that most of the reservation land had not been surveyed made it easy to claim that reservation boundaries did not include some of the choice sites on which the squatters moved, sometimes taking over buildings, fields, and livestock belonging to Indian families. In the early 1880s, Helen Hunt Jackson and Abbot Kinney were sent by the U.S. Congress to visit reservations and report back to Washington. Like others who reported on visits to the Indians of the area, they made no mention in their report of the Chemehuevis at Twentynine Palms.

Matters came to a head in the late 1880s, when the Office of Indian Affairs ordered that squatters on the Morongo Indian Reservation be removed from the reservation by the county sheriff, whereupon the squatters sued the government. Since the political climate was such that they were apt to win their suits, Congress acted at last on recommendations made in 1883 by Jackson and Kinney. The Mission Indian Commission was established. It was provided with funds to visit southern California reservations and other Indian groups, and to make recommendations for improving the situation. Charles Painter, Albert K. Smiley, and Joseph P. Moore were named to the commission, and proceeded to southern California in 1890. It was they who finally recommended that land be set aside for the Indians at Twentynine Palms. Their report read as follows with respect to the people at Twentynine Palms:

This Commission recommends that there be established a reservation known as the Twenty-nine Palms, to consist of the following lands, viz:

The South-west quarter of Section thirty-three (33) in Township one (1) North, Range Nine (9) East, S.B.M.; and also the North-west quarter of Section four (4) in Township one (1) South, Range nine (9) East, S.B.M.

There are three families here having three houses and some cultivated fields: The head man is Chimahueva Mike. They have plenty of water and can be comfortable here. There is sufficient tillable land for their needs; the balance of the land in the proposed reservation is valuable grazing land.

The Indians were in possession of these lands as shown by the field notes as long ago as in 1852 (Mission Indian Commission 1892).

At first thought, it seems impossible that any of the commissioners actually visited the land they were setting aside. Had they done so, they surely would have known that 160 acres of land in the desert would not have provided a comfortable living for three families, nor would they have thought there was "plenty" of water. On the other hand, the 1880s were a relatively wet set of years. It was a boom time in San Bernardino and Riverside, where the orange industry was off to a great start. At Palm Springs, orchards planted by settlers were flourishing, and great plans were being made for developing a number of sections. A decade-long drought began in 1894. The orchards died, and the developers grand plans came to nothing. It is possible that Twentynine Palms was green and flourishing in 1891, though it is unlikely that the commissioners went there.

The establishment of the reservation, for which the Chemehuevi4 received a patent in 1895, placed them there under the dominion of the Mission Indian Agency. Had they lived closer to the agency, they might have been on the receiving end of occasional donations of food, farm machinery, and seeds. In fact, there is no record of any contact between Indian agents and Twenty-nine Palms until 1908, when Clara True was Indian agent. True saw to it that the reservation was surveyed, and tried to protect its water rights. On January 7, 1908, for example, she wrote the CIA, noting that at Twentynine Palms, "two days out in the desert, the few Indians have for several years not known their exact rights and have suffered cattle depredations by Americans who claim that the spring is not on Indian land. On what little investigation I can make in connection with the many things devolving upon me in the beginning of my work here, it appears that the cattle man may be within legal rights as the reservation is bounded by the San Bernardino Base Line the exact location of which must be determined before the Indians will know whether they have water or not. They have an ancient claim to the water and the intention of the reservation was to protect them but it seems doubtful if this is true (True 1/7/1908). She asked that Mr. Chubbuck of the Indian Irrigation Service to pass judgment on the issue, since he had been there to investigate and knew the problem.

4Some members of the group, at least, were part Serrano. Note the ancestry of Jim Pine, as described in Footnote 5.

In later years, True wrote that she had made several expensive trips trying to determine the proper legal boundaries of the reservation, even getting the field notes of Col. Washington, who did an early survey. She noted, however, that they never found it possible to prove that he had made an actual survey, and concluded that he had probably made up the notes "second hand." In the end, she set up "corners" that the surveyor admitted were "probable but not entirely authentic" and claimed the water hole for the Indians (True 5/3/1942).

She also discovered that the tribal cemetery was outside the reservation on land belonging to the railroad. She apparently initiated plans for the government to acquire the cemetery land for them by trade with the railroad. They received this land in 1911 (Trafzer 1997:83-84).

Neglect by the Mission Indian Agency may have saved the Twenty-nine Palms people from pressure to allot the land to individuals. Indians at Morongo Indian Reservation, with which the Twenty-nine Palms people were probably in fairly close contact, having relatives who lived there, fought allotment fiercely, as did the other Coachella Valley Reservations. Morongo was finally allotted in the 1920s, but the Twenty-nine Palms people were able to continue owning their land in common (1997:83-84).

From the point of view of the Twenty-nine Palms people now, as expressed by Trafzer et al. (1997), the establishment of the reservation transferred to the Indians 160 acres of marginal farm land in return for hundreds of thousands of acres rich in mineral and other resources that had been theirs in traditional times and were stolen by individual Americans with government concurrence. Even though it had probably become awkward for them to exercise their traditional custom of visiting places in what is now Joshua Tree National Park when it was time to harvest valued resources, their right to do so was probably implicit in the situation until the reservation was set aside. Now this right was restricted.

Joshua Tree National Park

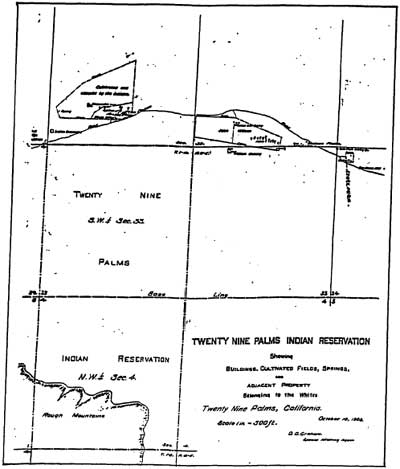

Map 3. The Twenty-Nine Palms Indian Reservation, 1908

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

In 1908, most of the people who then remained at Twenty-nine Palms Reservation moved to Morongo Reservation in the wake of the Office of Indian Affairs' determination that all Indian children should go to school. In this instance, they were forcibly enrolled at St. Boniface in Banning. Jim and Matilda Pine,5 a number of whose children were buried in the cemetery there, remained at Twenty-nine Palms, even though Clara True offered to get them land at Banning, Morongo Reservation or Mission Creek Reservation that was better for agriculture (Trafzer et al. 1997:85)

5Ramon has told the story of Jim Pine, whose father was Serrano:'Akuuki' was the name of our relative long ago. ('Akuuki' also means 'ancestor'). But he was not a close relative of ours. He was a distant relative, but we called him 'Akuuki' long ago. He was from Twentynine Palms. That was his territory. He was the only one left there. (They probably left Twentynine Palms around 1909). He moved away from there. They just took it all. Today the Americans live there. They all live there. That was his territory. There also used to be many Serrano living there. They used to have an extensive territory. Nowadays no one lives there. They all turned into something else (Mexicans or white people) long ago. Nowadays many people like Mexicans and others live there today. The white people have nice houses there. They are very big. There is a road through there. It is very beautiful there now. That land looks different now. That was his home long ago, the home of 'Akuuki', as we called him. He lived there ... he married a Cahuilla woman. He took a wife. Her name was Mathilde. 'Akuuki' had a father who was Serrano. His father, the father of 'Akuuki' was a Mamaytam Maarrênga 'yam Serrano. And his mother was a Chemehuevi or something. Long ago that man 'Akuuki ' could speak Chemehuevi. And he also must have known how to speak his father's language (Serrano). He also spoke that. He spoke Serrano. He also used to sing in Serrano long ago. I don't know how long ago this was. And then he moved over here. He lived here for a little while. Then he moved to Palm Springs. He went and died there (and is buried in Palm Springs). I don't know how long his wife lived after that. And then she too died. She is buried here at Morongo, as they say. Mathilde was his wife. She is buried here. That is all (Ramon and Elliot 2000:281-282).

5. The Willie Boy Story. Carlota, the daughter of William Mike, a Twenty-nine Palms Chemehuevi who had moved his family to the Gilman Ranch in the Coachella Valley near Banning, figured in a tragedy that rocked southern California in 1909, and has since been the subject of books and a movie. A cousin named Willie Boy, who had fallen in love with her, persuaded her to elope with him, their marriage having been forbidden because they were cousins. Her father tracked them and brought them back. Accounts vary with respect to what followed, but agree that Willie Boy shot and killed William Mike, perhaps by accident, escaped with Carlota into the desert, was tracked by a posse, and left Carlota hidden in a wash with his coat and waterskin. She died, either shot by the posse by mistake, or from exposure. According to Chemehuevi tradition, Willie Boy escaped, but has not been seen again (Trafzer et al. 1997:86-90).

The story of Willie Boy was the basis for Harry Lawton's novel, Willie Boy: A Desert Man Hunt, and a subsequent movie, Tell Them Willie Boy Was Here, starring Robert Redford, Katherine Ross, and Robert Blake. A number of Morongo Indian Reservation members played roles in the movie. More recently, historians James Sandos and Larry Burgess published The Hunt for Willie Boy: Indian Hating and Popular Culture, which incorporated valuable data contributed by Chemehuevis who were familiar with the events. Trafzer et al. have included the story as told by Chemehuevi Mary Lou Brown (1997:90-92).

6. Reservation Affairs. Although the members of the band for whom the Twenty-nine Palms reservation was set aside retained their identity as a group separate from the Chemehuevi who were members of the Chemehuevi on the Colorado River and those on various reservations in the Coachella Valley, they kept in touch with their fellow Chemehuevis. By the late 20th century, they had numerous family ties with other southern California Indians. In 1910, the government issued a trust patent for 640 acres jointly to the Cabazon and Twenty-nine Palms Bands of Mission Indians, and encouraged the Twentynine Palms Chemehuevi to live there rather than out in the desert at Twentynine Palms, which was so distant from other reservations that the OIA felt it too far for Indian agents to travel. This section was added to the already-existing Cabazon Reservation (Trafzer et al. 1997:94-95). When, in the course of time, conflict arose between the Chemehuevis and Cahuillas on the reservation, most of the Chemehuevis left, some of them returning, at least for a time, to the Twenty-nine Palms Reservation. Others "moved to live with the Paiutes in Nevada, Chemehuevis near Parker, Arizona, the Luisenos and Cahuillas at Soboba Reservation, the Agua Caliente Reservation in Palm Springs, or one of the other reservations in Southern California." Some went to live in the desert towns of the Coachella Valley or elsewhere (1997:95-96). The only Chemehuevi family who remained at the Cabazon Reservation was that of Susie Mike Benitez (1997:96).

Four hundred acres of the 640 acres held jointly by the two bands was allotted to eight Cahuillas and two Chemehuevis (1997:96), a division of the allotted acres that gave four times as much land to Cahuillas as to Chemehuevis. In the early 1970s, the Chemehuevis, feeling that they had never been full parties in the reservation, began to press for a larger share of the section. Because the Cabazon Tribal Council was at the time investigating the possibility of economic development, and especially Indian gaming, it was likely considered advisable to clear title to their land by bringing to an end the joint tenancy of the 240 remaining acres of the section. The Council, after due deliberation, decided that the 240 acres of the section held in joint tenancy that had not been allotted should go to the Twenty-nine Palms Band in view of the fact that members of that band had received less than the Chemehuevi share of the allotted 400 acres. The Tribe thereupon petitioned Congress that Section 30 be divided between the Cabazon Reservation and the Twenty-nine Palms Reservation, with the latter receiving the 240 acres plus $2,825 in cash plus interest. Congress under the terms of Public Law 94-271 authorized the division in 1976. This division of a reservation between two groups has been extremely rare in the history of this country. Now the Twenty-nine Palms Band had a land base in the Coachella Valley to which they had clear title, except that the acreage was diminished by rights-of-way for a storm channel and an irrigation pipeline granted the Coachella Valley County Water District, a California state highway, a road used by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, and Interstate 10 owned by the U.S. government (Trafzer et al. 1997:98-101).

7. Recent Years. In the 1980s, the members of the Band decided to start a tribally owned business on their land. Band members who had had business experience elsewhere returned to the Coachella Valley and made a considerable contribution to the project. In January, 1995, taking advantage of the fact that highway rights-of-way passed through the land they owned, they opened the Spotlight 29 Casino on it. In addition to gaming, it offers its patrons popular music and other entertainment, as well as Native American singing and dancing. They have also opened a first class restaurant for their patrons (1997:108-114).

jotr/bean-vane/history5.htm

Last Updated: 02-Aug-2004