|

Katmai

Building in an Ashen Land: Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 10:

FISHERIES RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT

TODAY, BRISTOL BAY is widely known as having the world's most plentiful stocks of wild sockeye (red) salmon, and the Naknek River system that flows out of Katmai National Park has long been known as one of the primary contributors to the bay's salmon stocks. The many streams that flow eastward from the park into Shelikof Strait, and the upper reaches of the Alagnak River drainage system, also boast healthy salmon populations, though not to the extent of the Naknek River system. Commercial fisheries interests, not surprisingly, were quick to respond to the area's abundant salmon populations, and in order to preserve the salmon's long-term abundance, government scientists and regulators have had a long-term management presence in the Naknek drainage. These activities are manifested in the Lake Brooks Field Laboratory, the Brooks River fish ladder, and other cabins and structures that have been related to fisheries research and management.

Initial Management Activities

As noted in the Chapter 7, the first area canneries were located on Kodiak Island (east of the present-day park) and along the Nushagak River (northwest of the park) during the early 1880s. By the mid-1880s, the remarkable Bristol Bay salmon resource was becoming widely recognized, and in the 1890s salteries and canneries were located along the Naknek River, just west of the present park boundaries.

Shortly after World War I, fisheries managers began to enter the Katmai area. The U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, a predecessor agency to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, decided to undertake a predatory fish destruction program in the various major Bristol Bay tributaries. The agency undertook such a program because salmon, at that time, was the only fish desired by local canneries. Therefore, any species that preyed on salmon was considered undesirable, and trout were specifically identified for destruction. As part of that survey, the Bureau sponsored a broad survey of fish populations; the agency studied the Naknek River system as well as other major Bristol Bay drainages. In early June of 1920, a four-man party headed by A. T. Looff of the College of Fisheries, University of Washington, began its Naknek Lake investigations.

|

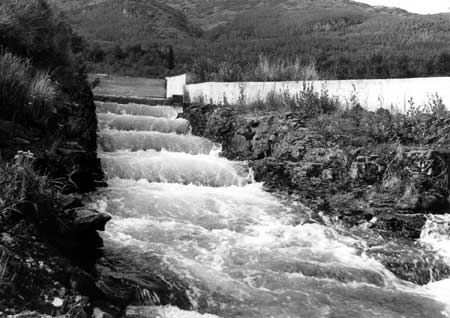

| Salmon ascending Brooks Falls. Photograph by Steve Buskirk. NPS Photo Collection, slide 4970-2-5750. |

Looff and his crew quickly surveyed the margins of the lake and found that "practically all the fish entering [upstream into] Naknek Lake either pass up Kidawik Creek [Brooks River] or Simenoffsky [Savonoski] River." [1] Kidawik Creek, in particular, was judged to be "an ideal salmon stream with fine spawning bottom ... where good numbers of lake trout and some Dolly Vardens were taken." The party camped at the creek mouth, then ascended to "a waterfall from 5 to 8 feet high, over which it would be impossible for fish to ascend during low-water stage." In an attempt to improve its spawning possibilities, the crew proceeded to modify the north side of the falls. By using "several stone-cutting gads, a steel bar, top maul, hammer and pick," they made a cut "10 feet in width, sloping back about 15 feet, through which the fish could easily pass." The following year, a better-equipped crew returned to the site and used dynamite to widen the slot. [2] Brooks River, at this time, was not part of Katmai National Monument.

Fisheries crews returned to Naknek Lake and the Brooks River each year from 1920 through 1925; in 1924 and 1925, they also included Lake Coville and Lake Grosvenor in their investigation. During that time, they killed more than 13,000 sport fish, primarily rainbow trout, lake trout, and Dolly Varden. The Bureau of Fisheries ignored Naknek Lake for the next decade. Below the lake, however, the Bureau remained active. In 1928, it established a fisheries station five miles upriver from Naknek, and maintained a salmon-counting weir at the site until 1932. [3]

In 1936, biologists showed renewed interest in the Lake Brooks area, which had been added to Katmai National Monument five years earlier. They noticed that Brooks Falls was not a block to red salmon under normal conditions. During seasons of low water, however, they observed that many died unspawned below the falls, presumably because of injury caused in attempting to negotiate them. Based on that overview, they made plans for "blasting steps in the falls" in the spring of 1937. Those plans, however, were put on hold for the time being. [4]

In 1938, concern about Japanese offshore fishing in the Bristol Bay area brought about a renewal of interest in Katmai's fisheries resource. Congress directed an investigation of the salmon fisheries of Bristol Bay. The plan, conceived in 1938, was to have one team of investigators in the bay tagging and marking fish, while land-based teams would set up operations along the five major bay drainages. The following year the Naknek River received a three-man team, which made a survey of the river system's major spawning grounds. [5] In 1940, the Bureau of Fisheries decided to concentrate their Naknek basin research efforts along the mile-long Brooks River. Fisheries personnel were well aware of the stream's abundant fish runs and felt that the stream was representative of others draining into Bristol Bay. [6]

Construction of Management

Facilities

|

| Above: The Lake Brooks Field Laboratory is long associated with the federal fisheries investigations and research of the Bristol Bay watersheds as well as the Lake Brooks area. Looking at the south elevation in this 1957 photograph taken by Ranger Warren Steenburgh. NPS-AKSO List of Classified Structures KATM file. |

Because of the agency's decision to concentrate on the Brooks River fish runs, the first government building was constructed in what is now Katmai National Park and Preserve. As has been described in more detail below, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in 1941, began building a field laboratory at the eastern end of Lake Brooks. (That same year, F&WS personnel also built and began operating a second station just below the Naknek River rapids, a few miles southwest of Lake Camp.) Construction on the center section of the log Lake Brooks field laboratory was completed by the close of the 1943 field season. In addition, the agency constructed a salmon-counting weir and a rough road connecting Brooks and Naknek lakes. Based on those improvements, the agency carried on a successful fish research and management program, one that was to last at that location for more than thirty years.

Fisheries research in the Naknek drainage continued during World War II. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel at the Brooks River weir counted escapements into Lake Brooks of 97,496 sockeye salmon in 1940, 125,948 in 1941, 360,899 in 1942, 272,929 in 1944, and 184,319 in 1945. [7] Construction of a wooden weir each year allowed fisheries personnel to make an exact fish count; the weir was set up and removed each season.

At war's end, F&WS biologists began tagging studies on Brooks River and aerial spawning ground surveys on the entire Bristol Bay watershed. "Index areas" were identified on each of the main river systems and photographed each year. Researchers then counted fish in the photographs and, as before, developed annual statistics. [8] Throughout this period, the National Park Service had only the vaguest idea of what Fish and Wildlife Service personnel were doing along the Brooks River and elsewhere in the monument.

|

| Current appearance of the Laboratory as it faces the lake. 1998 photograph taken by Janet Clemens. NPS-LAKA Studies Center. |

No sooner had the F&WS become involved in managing the Naknek River drainage's fish runs than they also became active managers of the salmon resources along the monument's eastern shoreline. The U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, the F&WS's predecessor agency, had established a Kodiak office in 1924, and ever since, the agency had made intermittent studies of the salmon spawning areas along the monument's eastern shore. In 1941, the Alaska Game Commission agent at Kodiak noted that the Bureau of Fisheries (which had become part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service the year before) had two watchman's cabins on the south side of Kaflia Bay. Why they were located there is uncertain; because there were no fish traps in the area, the cabins were probably associated with a salmon research study. [9] As noted above, salmon (and clams) had been processed at nearby Kukak Bay from 1924 to 1932 and from 1935 to 1936; thus agency management activities were probably related to that commerce. [10]

The Fish and Wildlife Service made no overt moves to manage the fishery along the monument's eastern shoreline for the remainder of the 1940s. The agency, instead, focused its management activities at its Lake Brooks field laboratory and at other sites within the salmon-rich Naknek River drainage. Recognizing the value of the Brooks River salmon run, agency personnel made repeated attempts to construct a fish ladder to circumvent eight-foot-high Brooks Falls. As noted above, the Bureau of Fisheries had initially proposed a fish ladder in 1937, and in the early 1940s new plans emerged for the project. But the latter attempt was foiled due to a reduction in personnel caused by the onset of World War II. [11]

In 1947, engineers and biologists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Montlake Laboratory at Seattle unveiled a new proposal for a Brooks River fish ladder. Unencumbered by financial or personnel difficulties, the agency's proposal was quickly put into action. The following year, a four-man crew arrived at the site and began constructing a ladder on the south side of the falls; the ladder had seven pools, each one foot above the other. Construction took more than two years, and the ladder opened on August 7, 1950. Willie Nancarrow, who was serving as Katmai's NPS ranger that summer, reported that "in the next week a marked increase in the number of fish going through the weir could be seen." [12] Some NPS officials were chagrined that the F&WS had built the facility without the NPS's permission; Regional Director Owen Tomlinson, for example, protested that "this structure hardly complies with Park Service principles relating to the preservation of natural structures." [13] But the F&WS insisted upon the right to continue using the structure. The fish ladder remained in operation for more than twenty years.

For the remainder of the 1950s, the agency vacillated from year to year in the interest it showed toward Bristol Bay research efforts. Funding during some years allowed tagging programs, foot and photograph surveys, and similar research efforts. But during other years, the F&WS decided to focus its Alaskan research efforts away from Bristol Bay. The Brooks River weir counts continued, but most other western Alaskan investigations were placed on hold. Regardless of funding levels, the agency continued to staff the Lake Brooks field laboratory and maintain the adjacent weir. [14]

The first scientific look at the sport fishing potential of and assessment of sport fishing pressures in the area came in 1954. At the request of the NPS, John Greenbank of the F&WS did a sport fish survey of Katmai National Monument. Greenbank and assistant Ronald Lopp worked through the summer of 1954 and described monument waters, examined fish distribution and abundance, sampled fish populations, and conducted creel censuses in various locations. Overall, the survey found fish populations high and fishing pressure light. Most fishing within the monument occurred in Brooks River. [15] In retrospect, the work was particularly significant because neither the NPS nor the F&WS conducted significant research into Katmai's sport fish populations in the two decades following Greenbank's survey work.

Diversification of Fisheries

Research

In 1960, commercial fisheries research in the monument underwent a major change when the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries decided to expand its fisheries research from Brooks River to the entire Naknek drainage system. The Lake Brooks field laboratory became a coordinating center, and to provide for its expansion, new housing was needed. Just south of the field laboratory, the BCF constructed two 28' x 36' four-room log cottages along with a 12' x 20' log garage. [16]

By 1962, studies were being conducted at remote sites within the monument, and to support those studies, the agency built several remote cabins in the monument. By 1965, the agency had built one at the east end of Lake Coville, just west of NCA's Grosvenor Camp, and it had occupied another cabin located two miles above the mouth of American Creek. [17] A third BCF cabin, located at the southeastern end of Lake Grosvenor, was built in the late 1960s. In 1969, it was described as a plywood one-room tent frame type cabin with two adjacent storage sheds which was being used for anadromous fish research. All three temporary camps were still active in 1971. The BCF, during the 1960s and early 70s, also had fish weirs and counting fences on Hardscrabble Creek and at the outlet of lower Kaflia Bay. Therefore, the agency probably erected rude shelters of some sort at those locations. By 1971, each of these shelters had probably been abandoned. [18] Meanwhile, the salmon counting activities along the Brooks River were discontinued after the 1967 season, and the fish weir was removed for the last time; those activities had been the mainstay of the BCF's work for more than 25 years. [19]

A continuing sore point that marred relations between the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service throughout the 1950s and 1960s was the Brooks River fish ladder. Throughout the 1950s, for example, the NPS wanted to get rid of it, while the F&WS defended it. [20] In the mid-1960s, the NPS formalized its principles of aquatic management, which led to an immediate push to do something about the Brooks River fish ladder. The F&WS fought the prospect. [21] Park Service field personnel, however, continued to raise the issue, noting in 1970 that when the ladder was open it greatly reduced the number of salmon that could be seen trying to leap the falls. [22] In 1973, they blocked the ladder's upstream exit with wood planks. It remained blocked for years afterward. But some water now passes through the ladder, and intermittent fish passage occurs.

In 1970, the Fish and Wildlife Service split into two parts: the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The work at Katmai, which had been administered by the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, was transferred to NMFS. The new agency continued the work of the old. In 1973, NMFS conducted the second year of a Naknek Lake salmon incubator project and also conducted limnological and biological sampling of the lake system. The following winter, however, the incubators froze and the project was abandoned. NMFS did not staff the Lake Brooks field laboratory in 1974 or thereafter. [23]

To a large extent, NMFS ignored the monument during the mid-1970s. In 1976, the agency began allowing NPS personnel to use the Lake Brooks cabins. The following spring, it decided to transfer its facilities to the Park Service. In 1979 the NPS, under the direction of interim superintendent Roy Sanborn, rehabilitated the two Lake Brooks cottages, and the Lake Brooks field laboratory—then known as the Lake Brooks National Marine Fisheries Research Station—was converted into a residence. That summer, and each summer since, NPS personnel have used the buildings. [24]

The various remote NMFS structures have not fared as well. The primitive cabin at the east end of Lake Coville remained active as part of a salmon fisheries research project until 1972. By the following year, however, it was "not fit for habitation without minimal repairs" and was abandoned. In 1985, NPS rangers lived in the cabin, which by then was dilapidated. The cabin was torn down the following year. Along American Creek, the former BCF cabin remained active from 1963 through 1970 but was afterward abandoned. The cabin at the southeast end of Lake Grosvenor was also used for only a short time. It was abandoned in the early to mid-1970s. [25]

Although most of Fish and Wildlife's facilities in Katmai were established on the Bristol Bay side of the monument, the bureau was also concerned with the Shelikof Strait fishery. Prior to statehood, it claimed jurisdiction of all areas below the mean high tide line. (It also, as noted above, claimed jurisdiction over commercial fish throughout the monument.) It carried out occasional patrols in the strait during the 1950s. In addition, the F&WS made scattered attempts to monitor the fisheries resources on the monument's eastern shore. The agency still maintained its watchman's cabins on Kaflia Bay, and in the summer of 1953 the agency stationed a salmon-stream guard in a tent about one mile south of the Kaguyak Village site. Both improvements may have been erected in conjunction with a nearby fish trap. [26] The agency, during the 1950s, may also have been active on other portions of the coastline.

After statehood, much of the fisheries management along the Shelikof Strait was transferred to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. The ADF&G sought a site from which it could manage, survey, and patrol the salmon and clam fisheries along the monument's eastern coastline, and in March 1962 it obtained a ten year Special Use Permit from the NPS for a site on Kashvik Bay, up to three acres in extent, in which to erect one or more field structures. By June, the ADF&G had decided to erect a weir, cabin, and storage shed at the site. Agency personnel used the cabin for the next several years as a base camp for monitoring and patrolling the area. [27]

At Amalik Bay, twenty miles northeast of Kashvik, the state erected a small fueling station in 1962. [28] That may have been the same structure as a 16' x 16' cabin that the ADF&G built during this period in the bay's northwestern cove. Supervisory fish biologist Jack Lechner, then stationed at Chignik, used the cabin to establish a field headquarters for the studying of salmon smolt each spring. Ever since that time, Kodiak-based fisheries agents have used the cabin each March to perform pre-emergent salmon smolt counts. Its continuing utility was reinforced by the decision, in 1985, to replace the cabin's roof, reinforce several walls and to perform other cabin rehabilitation activities. [29]

Since the mid-1970s, both the National Park Service and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game have undertaken a wide range of fisheries management projects within Katmai's boundaries, and additional research into the area's offshore fisheries resources has been undertaken by both the NPS and the Fish and Wildlife Service. Most of those studies, however, required nothing more than temporary tent camps by agency field personnel, and no permanent buildings have been constructed in recent years to support fisheries research or management activities.

Historic Property Summary and

Recommendations

As has been noted in the above chronology, the chief federal and state fisheries agencies—the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the USBF's successor), the National Park Service, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game—have conducted numerous fisheries management activities, over the past eighty years, within the boundaries of present-day Katmai National Park and Preserve. Most of those research, survey, and monitoring projects have required only a minor, temporary staff presence, and as a result most structures related to fish management activities are either rude cabins, wooden outbuildings, or tents, or weirs. (Examples include the Brooks River fish weir and the Kashvik Bay fisheries cabin.) Two structures, however, warrant more serious consideration because of their size, permanence, and central role in area fisheries management. Those structures are the Lake Brooks Field Laboratory, near Brooks Camp, and the Brooks River fish ladder.

The Lake Brooks Field Laboratory, also known as the Lake Brooks National Marine Fisheries Research Station, is located on the eastern shore of Lake Brooks, just 35 yards south of the Brooks River. (It is known as NPS building number BL-3 and Alaska Heritage Resources Survey Site XMK-124.) It is situated among spruce, willow and other vegetation, approximately 60 feet back from the lakeshore. The building initially served as a headquarters, staging area, laboratory and residence for the crews involved in the Bristol Bay Investigation. Early laboratory use was related to specific salmon research in the Naknek-Brooks lake area; it then expanded to include various Bristol Bay watersheds. Personnel from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the National Park Service have lived and worked in the building over the years.

In 1938, Congress directed an investigation of the salmon fisheries of Bristol Bay, including the Naknek River system, in response to concerns about Japanese offshore fishing. The Lake Brooks area was selected as the headquarters site for the Investigation because it was centrally located in the Bristol Bay freshwater area, permitted aircraft access in most weather, it had good runs of sockeye salmon, and provided a good subject area for specialized research. (George Eicher, a former director of the laboratory, has noted that the main purpose for the Bristol Bay Investigation—one that was kept quiet for decades—was to show the effects of Japanese fishing. Somewhat later, the laboratory's primary purpose became one of providing data to buttress the U.S. position during the development of the 1953 North Pacific Fisheries Treaty. This purpose was revealed to the investigators only after the treaty had been implemented.) [30]

The Fish and Wildlife Service, in consultation with the NPS, designed this cross-shaped 59' x 29' log building. It reflects the Rustic Style that the NPS developed and used to guide park development during the 1920-40s. The Rustic Style design ethic encouraged making buildings look as it they were constructed by frontier craftsmen using primitive hand tools and using natural materials of the same scale as the surrounding landscape. To fit the Rustic Style, the Laboratory building was designed to keep in scale with the surrounding landscape, and to look as if were constructed by frontier craftsmen using primitive hand tools and natural materials. [31]

Framing lumber for the building was shipped from Seattle to Naknek on the F&WS vessel Scoter in 1941. In preparation for constructing the Laboratory, the Bureau of Fisheries employees cut outside logs from around the Mount Kelez area, and placed them to dry in 1940. That same summer, crews transported materials for building the cabin and the Lake Brooks fish weir from the old Fish and Wildlife station along the Naknek River (near today's King Salmon) to the Brooks River. To haul materials to the Laboratory, a road was developed (that continues to be used today) from the mouth of Brooks River at Naknek Lake to the cabin site.

Once the materials had arrived at the building site, summer fisheries crews worked on the laboratory in sections over time. Most of the 17' x 29' central portion was completed by 1943, although the impressive fireplace and chimney constructed in the middle of the center section was not begun until 1942. World War II slowed construction and research activities. In 1947, the agency decided that the building would begin serving as a deployment and service center for biological crews working in other Bristol Bay areas. In order to create space to process samples, therefore, work on the laboratory began again. (Recognizing the amount of time that would be needed to complete the building addition, the agency also constructed a small temporary structure, set up to the east of the laboratory building, that was used for processing samples until the north wing addition was completed.) The fireplace and chimney were completed in 1953; planned wings, measuring 14' x 21', were completed for both the north and south ends of the center section in 1957.

|

| The fireplace and chimney, built with local rocks and stones, is a dominant feature of the laboratory. 1998 photograph taken by Janet Clemens. |

Varied materials were used in constructing the laboratory. Most of the outside walls were constructed of peeled round spruce logs. The 1943 center section and the north wing of the building were constructed using horizontal logs with double saddle notching. The imposing fireplace and chimney is made entirely from local river cobbles and boulders; the stovepipe from the wood cook stove is attached to this chimney. The original foundation is concrete and rubble rock. The materials and craftsmanship used in erecting the wings complements the central section so well that the entire building appears to have been built at the same (1940s) time period.

To enhance the building's rustic appearance, false rafter ends and purlins were part of the original plan. The false rafter ends were constructed using round logs at each rafter end. The false rafter ends were notched and attached to the milled Douglas fir rafter ends. In the center section at the gable ends, false log roof purlins were installed that extend 2'6" into the room. False purlins were also installed in the north and south wing gables.

The Lake Brooks laboratory is significant because it served as one the major Bristol Bay-area fisheries research headquarters for more than thirty years. The Bristol Bay Investigation's consistent research philosophy and activities provided for a continuity of records, which were used to manage the Bristol Bay fisheries and to provide data for development of the North Pacific Fisheries Treaty of 1953. In addition, Laboratory personnel constructed and used the Lake Brooks weir and the Brooks Falls fish ladder for specific salmon research in the Naknek-Lake Brooks area. The fisheries laboratory is the oldest substantial building in the present-day park, and the first building in the park built by a public entity.

The building served as an administrative center for staging local operations and for studies. Fish and Wildlife Service biological crews arrived at the station and were deployed into the Bristol Bay area. Over the years, the crews gathered a wealth of salmon data. Investigations conducted from the laboratory included collecting scale samples at canneries and streams, aerial and ground surveys of spawning grounds, tagging and crowding studies, and fingerling sampling. Additional activities included tagging salmon, marking juvenile salmon, making spawning ground surveys, and performing aerial spawning ground counts of salmon, including photographic coverage of index areas in all of the major Bristol Bay watersheds.

Beginning in 1961, the Bristol Bay Investigation changed its research direction and expanded its activities to the entire Naknek drainage system. The Field Laboratory expanded its coordinating activities, and for more than a decade, fisheries management agencies—first the Fish and Wildlife Service, later the National Marine Fisheries Service—built additional cabins, weirs, and counting fences in Katmai National Monument. While the agency maintained counts, studies shifted to on-the-ground experiments. This change in management philosophy eventually de-emphasized the need to maintain a strong central headquarters presence. Fish counts along the Brooks River were stopped in 1967, and in 1974 NMFS decided that the laboratory no longer needed to be staffed. The National Park Service acquired the building in 1979. The new agency decided to use the building for employee housing, and several modifications (including a metal instead of a shingle roof) have recently been effectuated consistent with that purpose.

The building is part of the Brooks River Archaeological District National Historic Landmark (AHRS # XMK-051) and has been judged as a non-contributing element to that NHL. Recognizing its historical importance, however, it is suggested as part of this study that the Lake Brooks Field Laboratory is significant under National Register Criterion A (for "properties that are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history"). This significance has been suggested even though Criterion G applies (for properties that are either less than 50 years of age or for properties that have achieved significance within the past 50 years). Park contract personnel recently completed a Determination of Eligibility for this building. The State Historic Preservation Office's response to that study determined that the property was eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places; the agency did, however, have some concerns that needed to be addressed before formal listing could take place.

The other major historic property in Katmai National Park and Preserve related to fisheries research and management is the Brooks River fish ladder. This structure is one of the few fish ladders in southwestern Alaska and one of the few (perhaps the only) fish ladder within a National Park Service unit.

|

| The Brooks River Fish Ladder is associated with the Fish and Wildlife Service's fisheries research. During the early 1970s, the NPS placed planks over the upper end of the ladder. This photo was taken by Victor Cahalane in August 1954. NPS Photo Collection, neg. 12,049. |

As noted above, Bureau of Fisheries personnel became concerned about aiding fish passage over Brooks Falls in 1920. Using hand tools at first, then dynamite, they smoothed out a rough pathway around the north end of the falls during the summers of 1920 and 1921. Fifteen years later, the agency first considered and planned the installation of a fish ladder around the falls' south side. For the next ten years, agency personnel periodically sought the funds to construct the facility. Throughout this period, the falls were located within the boundaries of the newly-expanded Katmai National Monument, but the USBF which became part of the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1940 made no mention of its plans to the National Park Service, because they apparently thought that the NPS would be unconcerned about such a minor structure.

In 1947, F&WS engineers designed the fishway, and in 1948 materials for the ladder were flown to Lake Brooks or extracted locally. [32] Four U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employees John Hurst, Mike Michel, Mike Wold, and Jerry O'Neil blasted and hewed the ladder from solid rock to make it as natural-appearing as possible. Ten feet in width, the ladder had seven pools, each one foot above the other. A headgate metered water into the topmost pool. The fisheries employees completed the ladder, except for the bottommost pool, in 1949. [33] The remaining portions were completed early the next summer, and the ladder opened on August 7, 1950. [34]

The first NPS employee to become aware that a fish ladder was in the offing was Alfred Kuehl, a landscape architect in the agency's regional office in San Francisco. Kuehl visited the site in August 1948, while F&WS engineers were still finalizing plans for the ladder. [35] Kuehl, accompanied by the regional office's assistant regional director Herbert Maier, returned to the site a year later during the midst of construction work. Neither protested the construction, either during or immediately after their visit. [36] But in June 1950 another NPS employee, George L. Collins of the Alaska Recreation Survey, arrived at Katmai. Collins, quite clearly, was perturbed at what he saw and demanded to know who had allowed such a travesty to be built in an NPS unit. [37] The NPS, in turn, asked the F&WS why it built the ladder without authorization. The F&WS, in response, admitted that it had never asked for permission to build the ladder; it noted, however, that neither Kuehl nor Maier had expressed any objections while visiting the construction site. The mixed messages that the NPS was conveying, combined with the obvious fact that the fish ladder was an accomplished fact, prevented the NPS from stopping the new facility. The incident, however, rankled feelings between the two agencies for years afterward. [38]

When the construction of the fish ladder began, the Fish and Wildlife Service was the only federal agency with an active, ongoing presence in Katmai National Monument. As such, fish management (lacking other activities) was a primary governmental function in the Lake Brooks and Brooks River area. But in 1950, Northern Consolidated Airlines constructed five fish camps in the country west of the Aleutian Range; one of these camps was located at the mouth of Brooks River. As a result of this development, and the commencement that same year of an active presence by an NPS seasonal ranger, the focus of activity at the monument began to change.

Throughout the 1950s, the primary activity in the Brooks River area was the seasonal operation of the NCA fish camp, and the NPS presence was minimal. NPS officials made continued protests about the ladder, but the F&WS, which strongly supported its existence, rebuffed them. But by the early 1960s, the F&WS began to change its philosophy toward fish management, and Katmai National Monument began to attract visitors in large numbers who had little interest in sport fishing. Based on these trends, the fish ladder became increasingly anachronistic. In 1973, the National Marine Fisheries Service (the successor to the F&WS) vacated the area; that same year, NPS personnel blocked the fish ladder. Although the NPS's action did not succeed in preventing some water—and some fish—from using the ladder, the facility has been largely unused in recent years.

Because the NPS and the various fisheries agencies have had strongly differing attitudes toward the utility of the fish ladder, the facility has been the focus of several studies over the years. Perhaps predictably, studies sponsored by fisheries agencies have concluded that the fish ladder has had a significant effect in boosting the success of the Brooks River salmon run. NPS studies, by contrast, have concluded that the river's salmon run had been successful for hundreds of years before humans had ever intervened and that the fish ladder's "success" has been either inconsequential or irrelevant to NPS management goals.

The Brooks River fish ladder, therefore, is significant because of its relative (perhaps absolute) rarity among fishery-enhancement facilities within an NPS unit. It is also significant because it has been both a symbol of contention between the management philosophies of the various federal agencies toward fisheries management, and because it also symbolizes the changing role of fish ladders in the research process within federal fisheries agencies. It is thus worthy of consideration as a property to be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, which identifies properties that are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history. It is recognized that other NPS policies—both management policies and natural resource management policies—frown on either the physical modification of streambeds or on habitat manipulation. [39] As a physical feature, however, the Brooks River fish ladder appears to have potential historical importance.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries, 1920 (Washington, GPO, 1921), 31-32.

2 U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries (Washington, GPO) for 1920 (p. 32) and 1921 (p. 17); NPS, Draft Environmental Assessment, Brooks Falls Fish Ladder, Katmai National Park and Preserve, May 1987, 16. Many sources have stated that the original cut was located where the fish ladder was later built. Both the USBF and Frank Been's Field Notes of Katmai National Monument Inspection (p. 11), however, confirm that the 1920-21 activity took place across the river from the fish ladder.

3 U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries (Washington, GPO), 1920-25 editions; Frank T. Been, Field Notes of KNM Inspection, November 12, 1940, 8; Alaska Travel Publications, Inc., Exploring Katmai National Monument and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes (Anchorage, the author, 1974), 76.

4 U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries, 1936, 284; George J. Eicher, "The Effects of Laddering a Falls in a Salmon Stream," n.d. (1956?), AKSO-RCR Collection.

5 George J. Eicher, "History of the Bristol Bay Investigation," April 25, 1967, 1, ms. in files of the Auke Bay [Alaska] Laboratory, National Marine Fisheries Service.

6 Eicher, April 25, 1967, 1. Later it was discovered that Lake Brooks was the least typical of the Bristol Bay spawning and nursery areas.

7 Revised figures are from Eicher, 1971, as quoted by Carl Burger, with James Lundeen and Anders Danielson, "Biological and Hydrological Evaluations of the Fish Ladder at Brooks River Falls, Alaska" (draft report), U.S. F&WS, National Fishery Research Center, Anchorage, June 1, 1985, copy in AKSO-RNR files. No count is available for 1943.

9 Annotated copy of "Kamishak Bay-Katmai Region" (map), USGS/1923, in File 601, KNM Box 2, Entry 7, RG 79, NARA DC; Hillory Tolson (Acting Director NPS) to Edwin G. Arnold (Director, Division of Territories and Island Possessions), April 12, 1946, at KATM; William R. Heard, Richard L. Wallace, and Wilbur L. Hartman, Distribution of Fishes in Fresh Water of Katmai National Monument, Alaska and their Zoogeographical Implications, Special Scientific Report—Fisheries No. 590 (Washington, USF&WS), October 1969, 2.

10 U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Alaska Fishery and Fur-Seal Industries (Washington, GPO), 1947 through 1955 editions.

11 Annual Reports of Alaska Fisheries Investigations, 1943-1944, 1944-1945; Section of Alaska Fishery Investigations, September 1 to September 30, 1945, in Box 294, BCF Collection, 1904-1960, RG 22, NARA Anchorage; George J. Eicher to William S. Hanable, September 1, 1989, in AKSO-RCR files.

12 Ranger (Willie) Nancarrow to Supt. MOMC, August 26, 1950, in File A2827, Reports to Chief Ranger, January 1950-November 1954, DENA archives.

13 O. A. Tomlinson (RD/R4) to Director NPS, July 31, 1950, in File 714, KNM Box 312, Entry 7, RG 79, NARA SB.

14 Eicher, April 25, 1967, 10-12.

15 John Greenbank (Fishery Management Biologist, F&WS), "Sport Fish Survey, Katmai National Monument, Alaska," n.d. (c. 1955), in File N1423, KATM.

16 William R. Heard, Richard L. Wallace, and Wilbur L. Hartman, Distribution of Fishes in Fresh Water of Katmai National Monument, Alaska and their Zoogeographical Implications, Special Scientific ReportFisheries No. 590 (Washington, USF&WS), October 1969, 1; F. W. Stokes (BCF Administrative Officer) to GSA Seattle, March 31, 1960, in "Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, Brooks Lake Files" folder, AKSO-RCR Collection.

17 NPS, Master Plan Brief for Katmai National Monument, 1965, 17 (map).

18 Most of the structures erected outside of the BCF's three main temporary camps were built rudely and deteriorated quickly. Item 17, "Inventory of Backcountry Facilities and Structures," in Breedlove, 1969; Robert L. Carper, List of Classified Structures Inventory (Denver, NPS), April 1976; NPS, Final Environmental Statement, Katmai Wilderness, Katmai National Monument, Alaska (FES 74-35), June 13, 1974, 31, 37; William R. Heard, Richard L. Wallace, and Wilbur L. Hartman, Distribution of Fishes in Fresh Water of Katmai National Monument, Alaska and their Zoogeographical Implications, Special Scientific ReportFisheries No. 590 (Washington, USF&WS), October 1969, 1-2; NPS, "Important Issues Concerning Preliminary Wilderness Proposal for Katmai National Monument," in Box 13, NARA ANC.

19 NPS, Draft Environmental Assessment, Brooks Falls Fish Ladder, KATM, May 1987, 18. But Superintendent Gil Blinn, who arrived in September 1969, recalled that the weir was "discontinued about my first summer or so." Blinn interview, August 26, 1988.

20 George J. Eicher's analysis, "The Effects of Laddering a Falls in a Salmon Stream," (unpublished mss., USF&WS), c. 1956. Eicher ascribed the post-ladder sockeye salmon decline to overfishing in Bristol Bay and not to the presence of the fish ladder. He argued that the population of three salmon species—pinks, cohoes, and chums—were healthier in the 1950s (after ladder construction) than in the 1940s. But the average numbers of those three species (both before and after ladder construction) were less than one-tenth of one percent of the red salmon population. Contemporary biologists consider any differences in the number of pinks, cohoes, and chums to be so small as to be insignificant and inconclusive.

21 Darrell L. Coe (Management Assistant, KNM) to Supt. MOMC, March 27, 1967; George A. Hall (MOMC) to Assistant RD, WRO, August 19, 1967; both in AKSO-RNR files.

22 Vernon C. Betts (Chief Ranger, KNM) to Management Biologist (Alaska Office, NPS), July 21, 1970, in AKSO-RNR files.

23 NPS, Final Environmental Statement, Katmai Wilderness, Katmai National Monument, Alaska, June 13, 1974, 29; SAR for 1973 (p. 2) and 1974 (p. 2). Harry Reitz, the NMFS Alaska Director, noted in 1978 that the agency "had not maintained an active research program there since 1972." Reitz to RD/PNRO, March 20, 1978, in "Buildings" file, KATM.

24 "Brooks Lake General Correspondence" file, BCF folder, AKSO-RCR Collection; SAR 1978, 6; Morris interview, November 2, 1989.

25 Carper, List of Classified Structures Inventory, 4-5; Janis Meldrum interview, June 9, 1993.

26 Cahalane, A Biological Survey of Katmai National Monument, 178.

27 Samuel A. King (Supt. MOMC) to Dexter F. Lall (ADF&G, Kodiak), June 22, 1962; Special Use Permit KATM-1-62; both in Item 13 ("Special Use Permits"), Breedlove 1962; NPS, Master Plan Brief for Katmai National Monument, 1965, 17 (map).

28 Samuel A. King (Supt. MOMC) to Dexter F. Lall (ADF&G, Kodiak), June 22, 1962; Special Use Permit KATM-1-62; both in Item 13 ("Special Use Permits"), Breedlove 1962; Robert F. Cooney, "Preamble to Master Plan for Katmai National Monument," September 10, 1963; Kathy Jope to author, email, April 8, 1996.

29 NPS, Katmai Coast Field Season Reports for 1984 and 1985.

30 George Eicher, former Laboratory Director, unpub. mss. dated September 1, 1989, in Box 4, KATM/ANIA NPS Collection.

31 Laura Soullière Harrison, Architecture in the Parks National Historic Landmark Theme Study (Washington, NPS, Nov. 1986), 7-8.

34 Ranger (Willie) Nancarrow to Supt. MOMC, August 26, 1950, in File A2827, Reports to Chief Ranger, January 1950-November 1954, DENA archives.

35 Alfred C. Kuehl to Assistant Regional Director, Design and Construction, Region Four, August 21, 1951, in File N1423 ("Fish, 1946-1959"), KATM; George J. Eicher to Dean Paddock, March 21, 1987, in AKSO-RNR files.

36 Alfred C. Kuehl to Assistant Regional Director, Design and Construction, Region Four, August 21, 1951, in File N1423 ("Fish, 1946-1959"), KATM.

37 George L. Collins to RD/R4, NPS, July 19, 1950, in "Katmai NM" folder, Box 312, RG 79, NARA SB.

38 O. A. Tomlinson (RD/R4) to Director NPS, July 31, 1950; Hillory A. Tolson (Acting Director, NPS) to Director, F&WS, August 25, 1950; M.C. James (Acting Director, F&WS) to Director NPS, September 27, 1950; all in File 208, KNM Box 311, RG 79, NARA SB; Eicher, September 1, 1989.

39 NPS, Natural Resource Management Policies (NPS-77), 1991, pp. 2:70 and 3:42.

katm/hrs/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 22-Oct-2002