|

Katmai

Building in an Ashen Land: Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 11:

TOURISM AND EARLY PARK MANAGEMENT

THE DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM in Katmai is intertwined with the active management of Katmai National Monument by the National Park Service (NPS). Beginning in 1950, the park concessioner's development of fishing camps and visitor services served, directly or indirectly, as a catalyst for NPS to establish its first ranger in the monument, thirty-two years after the monument's creation. The original concessioner's fishing camps were comprised of wall tents that were later replaced with prefabricated wooden cabins. NPS's first permanent (all-wood) buildings in Katmai were a ranger station and a boat house, both located at Brooks Camp.

Between 1956 and 1968, the major tourist-related improvements that are seen in the park today were erected. The concessioner improvements included new lodges and guest cabins at three camps and one lodge at a fourth camp. During the summer of 1962, NPS Mission 66 funding provided for a 22-mile road from Brooks Camp to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes; three Panabode cabins used for housing, and a fourth Panabode placed at Three Forks Overlook as a visitor facility; and the construction of various short trails leading from both Brooks Camp and Three Forks Overlook. [1] While Katmai's visitors during the 1940s and 1950s were almost exclusively sport fishermen, the construction of the so-called Valley Road helped attract non-fishing tourists and signaled the beginning of Katmai as a significant general-purpose tourist destination.

Early Tourism Patterns

Katmai National Monument was proclaimed in 1918, primarily as a scientific preserve at the behest of the National Geographic Society. Because the monument was remote from existing transportation routes, it had few visitors, and because the monument's resources were in little danger of degradation, the NPS completely ignored the area. Prior to the 1960s, the budget for all of the country's national monuments was miniscule, and for more than thirty years after its establishment, virtually no money was spent to develop or manage Katmai National Monument.

|

| Fishing at Katmai. Photograph by Standart. NPS Photo Collection, slide 3670-33-5250. |

During the 1920s, a handful of Katmai visitors used Kodiak as a jumping off point, just as the earlier National Geographic Society expeditions had done. Tourists typically crossed the forty-mile wide Shelikof Strait in small boats. Despite NPS plans to develop an access road in the mid-1920s, funding did not follow. The advent of aviation provided new opportunities for tourists to fly into the monument beginning in the late 1920s. Early tours of volcanic country were provided by Anchorage Air Transport and Anchorage-based Pacific International Airways. Beginning in the late 1930s, Bristol Bay Air Service and independent pilot John Walatka offered tours as well.

Pressure for NPS to take a more active role in the monument began following the 1931 monument boundary expansion. Reports of illegal hunting, trapping and fishing activities in the monument brought about a cooperative agreement that delegated hunting and trapping enforcement regulations to the Alaska Game Commission. In 1937, the first NPS Katmai patrol occurred; it amounted to a one-day flyover in which landings were made at Lake Brooks and at Savonoski. With lack of funds to provide a ranger staff, NPS had to rely on the cooperation of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to patrol Katmai for many years. Three years later, Mount McKinley National Park Superintendent Frank T. Been and wildlife biologist Victor Cahalane visited the monument on a more extensive trip. In a report on that trip, Been made a particular note about the Katmai country's beautiful lakes and splendid trout fishing; he also noted, however, that its remoteness precluded it from becoming a tourist center for many years. [2]

What Been could not have foreseen was the influx of military personnel that would soon be using the monument. In 1941, the U.S. Army Air Corps established Naknek Air Base at a location fifteen miles east of Naknek. (This site was renamed King Salmon Air Station in the 1950s.) Before long, two military recreation camps were constructed as well. Naknek Recreation Annex No. 1, also called Rapids Camp, was located and at the foot of Naknek River Rapids, while Annex No. 2, called Lake Camp, was located near the western outlet of Naknek Lake. The growth of these camps had little effect on the monument's fish populations, but the new access created by the air base brought hundreds of military and construction personnel into the monument; they flew in on small floatplanes to access rainbow trout fishing areas throughout the upper Naknek drainage. Charter aircraft services, particularly after the war, also flew growing numbers of sportsmen into the monument. [3] Despite that upswing in interest, the Katmai country prior to 1950 attracted only the hardiest, most independent fishermen.

Establishing the Concession

Camps

Throughout this period, the National Park Service's presence in Katmai was limited to occasional site visits, hampered as it was by lack of funding and agency direction. The agency was under an increasing amount of pressure to develop the monument in some aspect. The movement to supply visitor services and accommodations, however, came not from the NPS but from an airline executive, Raymond I. Petersen, who in late 1949 laid out a plan to set up a series of five tent camps in the lake country west of the Aleutian Range. Two of those camps—at Brooks River and Lake Grosvenor—would be located in the monument. The NPS wisely recognized that Petersen's proposal offered both tourist accommodations and access, and in March 1950 it signed a five-year concessions contract for his fledgling Northern Consolidated Airlines (NCA) tourism business. In less than three months, Petersen built all five tent camps; Brooks Camp, the linchpin of his system, opened its doors to the its first visitor on May 31, while guests arrived at Coville Camp somewhat later. The other three camps—Battle Lake Camp, Kulik Camp and Nonvianuk Camp—were located outside the monument boundaries; they were absorbed into Katmai National Park and Preserve when the Alaska Lands Act became law in 1980.

Petersen intended that the five tent camps would appeal to fishermen, primarily if not exclusively. The camps, therefore, were essentially rustic facilities—a series of tent frames covered by olive drab-colored G.I. tent material. Most of the construction materials were precut elsewhere before being flown into the camps. [4]

Brooks Camp, the largest of the NCA camps, was located just north of the Brooks River mouth, on Naknek Lake. The camp began as an eight- or nine-tent guest and employee complex. Most of the guest tents were nine feet square. As visitation grew during the decade, the number of guest tents grew, and by the end of the decade the camp boasted 22 buildings, including a 32' x 16' cookhouse, a bathhouse, a powerhouse, a storage shed, and a root cellar. Brooks, alone among the NCA camps, offered running water, flush toilets, and shower baths. [5]

Coville Camp, located along the narrow peninsula separating Coville and Grosvenor lakes, originally consisted of one 16' square cookhouse, at the south end of camp, along with one large and four smaller guest tents, a pump house, and a root cellar. In 1954, Dr. Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor—the longtime editor of the National Geographic Magazine and a major player in proclaiming the original (1918) monument—visited the site, and to commemorate their visit, Petersen changed the facility's name to Grosvenor Camp. The site has borne that moniker ever since.

Kulik Camp was originally located along the western shoreline of Kulik Lake, just north of its outflow into Kulik River. Due to prevailing high winds at the site, however, the camp was abandoned after its first year of operation and moved to its present site, a 10.64-acre tract located south of Kulik River and along the eastern shoreline of Nonvianuk Lake. (Ruins of the original camp may still be found.) The present camp, consists of one 16' square mess hall and kitchen, two other 16' square sleeping quarters, four 9' square sleeping quarters, and a root cellar. [6]

Battle Lake Camp, on a 3.98-acre site at the northern tip of the present park, originally consisted of one 16' square mess hall and kitchen, 2 other 16' square sleeping quarters, five 9' square sleeping quarters, and a pumphouse. The camp is located on the northeastern side of Battle River at the Battle Lake outflow.

Nonvianuk Camp is a 2.36-acre parcel located at the western end of Nonvianuk Lake. It is the smallest of the five NCA camps and the only one that is presently in Katmai National Preserve. NCA established the camp adjacent to the Hammersly Cabin complex; prospector Rufus K. "Bill" Hammersly had operated out of the site since 1938, and he helped operate the camp during its first few seasons. Facilities at the camp originally consisted of one 16' square tent, which served as a mess hall and kitchen, and two 9' square sleeping quarters.

During the spring of 1950, Northern Consolidated Airlines was not the only entity preparing to establish a presence in Katmai National Monument. Once the concessions contract had been signed, NPS officials recognized that the agency needed to establish a presence there both to provide information and to ensure that monument users followed NPS regulations. The Superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, in response, budgeted $2,000 for Katmai operations, and assigned a seasonal ranger, William Nancarrow, to patrol Katmai. Nancarrow arrived at Brooks Camp about July 1. As one of his first tasks in his new assignment, Nancarrow built a two-room wall tent, a cache, and a well. All were located at the present Brooks Camp campground, which is one-half mile north of the Brooks River mouth.

Facilities Development During the

1950s

Ray Petersen, NCA's president, and John Walatka, the company's superintendent of camp operations, cooperatively managed the five Katmai-area camps. The duo quickly recognized that the camps were commercially successful, and visitation to the camps grew consistently between 1950 and 1960. The three southernmost camps—Brooks, Grosvenor, and Kulik—were better suited for tourism growth than the other two, and in recognition of that fact, Petersen and Walatka decided to undertake a gradual improvement program.

Three primary elements constituted NCA's improvement program. First, most if not all of the camps' wall tents were replaced by plywood boards, then overlaid by asphalt shingling; second, new wooden buildings were constructed either of prefabricated, simulated log "Panabode" material or of locally-planed lumber; and third, attempts were made to improve access to the camps.

Structures made of Panabode material were constructed at several camps. In 1956 at Brooks Camp, NCA erected a combination store, office, and manager's quarters; it measures 20' x 24' and remains today. The following year, NCA constructed a similar Panabode structure at Grosvenor Camp. The combination manager's office, residence, and lounge measures 32' x 22'. By early 1960, further improvements at Grosvenor Camp included a bath house, two cabins of Panabode-styled cedar, four log buildings, six tent-covered structures, and a power house. [7] At Kulik Camp, NCA officials decided not to construct new buildings out of Panabode material; instead, they installed a sawmill and planing mill in 1956, and before long they began to prepare the materials to be used in the camp's large lodge building. The lodge was completed by 1960. The wood used in the camp's store and garage, completed somewhat later, also came from the nearby sawmill, as did the lumber for the Nonvianuk Camp lodge, located at the far end of Nonvianuk Lake. [8]

|

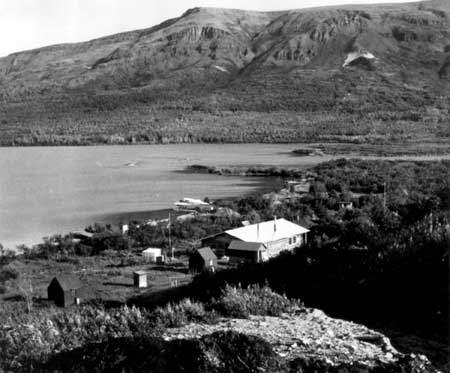

| Kulik Camp during the late 1950s included the lodge and a few tent frames covered with asphalt shingling. Wien Collection, AMHA. |

In order to improve access to the camps, NCA applied pressure along two fronts. At Brooks, it made repeated attempts to build an airstrip south of Brooks River. In 1954, it notified NPS officials that it demanded an airstrip in order to justify the construction of an expanded lodge facility. NPS Director Conrad Wirth, however, demurred. The construction moneys promised by Mission 66 gave renewed hope that an airstrip might be built, but agency officials were unwilling to expend funds under this program in such a remote, little-used monument. At Kulik, however, NCA had better luck. The company, because its facility was located outside of Katmai National Monument, had no difficulties in obtaining permission from the Bureau of Land Management to build an airstrip. In 1954 it roughed out a 1,500-foot gravel airstrip, which was lengthened to 2,000 feet the following year. Several years later, NCA decided to fly Fairchild F-27B propjets into Kulik, so it doubled the runway's length. Company officials were well aware that the new, longer runway exceeded the 80-acre allotment for which NCA had originally applied, but they waited several years before taking any action to legally justify its existence. [9]

The National Park Service, partly in response to NCA's increasing presence, also moved to establish new facilities in the monument. Most were located in or near Brooks Camp. Facilities constructed during the 1950s included a ranger station and a boat house.

|

| Brooks River Ranger Station, the first permanent NPS station in the park. NPS List of Classified Structures 1993 site visit. NPS-AKSO LCS KATM file. |

NPS plans to build a ranger station began during the summer of 1954 when logs were cut, peeled, and placed to dry for use the following spring at Brooks Camp. By February of 1955, NPS ordered building materials from Seattle and arranged for delivery to King Salmon by a Fish and Wildlife vessel. In July 1955, NPS personnel completed the ranger station, and soon afterward, the seasonal ranger in charge of monument operations, Dick Ward, disassembled the wall tent and cache where he had been living (one-half mile north of Brooks Camp) and moved into the new facility. At this time, the interior plumbing and cabinetry work had yet to be completed. This was the National Park Service's first permanently built structure in Katmai and its first ranger station, thirty-seven years after the monument had been established.

During the late 1950s, NPS staff added a generator shed, storage cache, fuel tank and weather instrument shelter at Brooks Camp. The log storage cache was placed in front of the ranger station, and although the original is gone, a replacement stands in the same location. The rangers also constructed two trails nearby.

NPS Katmai rangers built the boat storage house around 1960. During summer 1958, the rangers secured and stored building materials in sufficient quantity to construct a "small warehouse" at Brooks Camp for the following year. The boat house [10] was probably built during the summer of 1959, inasmuch as the building was complete when Ranger-in-Charge Robert Peterson first arrived at Brooks Camp in the spring of 1960. The Boat Storage House provided needed storage space and has taken on multi-use functions over the years. It has served as a winter storage area for agency watercraft, in the summer of 1963 it was used for visitor interpretive talks, and in 1964 it was being used as a VIP residence. Later uses include a visitor contact station and its current function as a ranger station.

The ranger station (BR-1) and boat house (BR-38), as originally constructed, complement each other in several ways: they are approximately the same size and shape; they exhibit the same use of materials (local logs painted or stained dark brown, with green metal roofs that were later changed to natural color wood shingles); and they have the same type of windows. The cabins, consistent with the Rustic Style, reflect similar cabin construction, materials and colors found in other national parks, including those at Mount McKinley National Park (now Denali National Park and Preserve), from where Katmai rangers were assigned.

|

| The Brooks River Boat Storage House is located close by and similar in appearance to the Ranger Station. NPS List of Classified Structures 1993 site visit. NPS-AKSO LCS KATM file. |

Expansion of Improvements Since 1960

Both the NCA and the NPS erected gradual improvements during the 1950s. During the winter of 1959-1960, however, NCA president Ray Petersen met with Mount McKinley Superintendent Samuel King and announced that in return for a twenty-year contract, he intended to "plan and finance substantial improvements of facilities in the Monument in order to accommodate the rapidly expanding tourist demand." King liked the idea of a twenty-year contract and gave that opinion in a letter to his superior. Petersen, meanwhile, got ready to move building materials to the Monument while the ice on the lakes still held. (Higher-ups, it turned out, refused to accept Petersen's contract idea; a year later, the NCA and the NPS signed a five-year contract.)

NCA spent much of the summer of 1960 constructing new facilities. By the spring of 1961, company personnel had completed building the mess hall portion of Brooks Lodge (BRC-19), which measured 50' x 24'. (A 20' x 20' kitchen was added on soon afterward.) The construction project also included seven 12' x 14' guest cabins (BRC-20-27) at Brooks Camp and one cabin at Grosvenor, as well as "a large approved cess pool," a power plant, and a new water system. A combination comfort station and bathhouse was constructed in the summer of 1961.

New NPS improvements took place in and around Brooks Camp in 1962, in large part because of a discussion held in February 1961 between NCA President Ray Petersen, NPS Director Conrad Wirth, and Alaska Senator Ernest Gruening. Before that meeting, the NPS had made no moves to expend Mission 66 funds on Katmai, one of the least-visited units in the NPS system, in part because Petersen's company held such influence over the monument. Gruening, however, angrily told Wirth that "you don't treat a constituent [Petersen] like this," and Wirth reluctantly agreed to fund certain improvements. Central to Petersen's plan was a 22-mile road that would allow Brooks Camp visitors to easily access the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. That road was constructed during the summer of 1962. In order to house the construction workers, three Panabode cabins were built in Brooks Camp that year, and a warehouse was built in 1963. Other improvements that followed in the wake of road construction included a 24' x 28' reception center at Three Forks Overlook (at the southeastern end of the Valley Road) and various area hiking trails.

|

| View of the Brooks Camp prefabricated Panabode guest cabins, built between 1960 and 1961. Looking northwest to Dumpling Mountain in 1971. Wien Collection, AMHA. |

As a direct result of the facility upgrade at Brooks Camp, and the construction of the Valley Road, Katmai began to appeal to general visitors as well as sport fishing enthusiasts. Annual visitation began to increase dramatically—from less than 350 in 1962, to more than 1,000 in 1967, to more than 10,000 in 1970. These new visitors demanded the construction of a number of new structures; those built in the 1960s included a ten-unit guest-cabin complex (called the Skytel), constructed in 1964-65, and two NPS employee guest cabins, built in 1967. Another structure worked on in 1967 was the reconstruction of a prehistoric house (the Brooks River barabara) just west of Brooks Camp. Only two or three additional buildings were constructed at Brooks Camp during the 1970s: they include an auditorium and a generator building. Few buildings were constructed at the other Katmai camps during the 1960s or 1970s. Since 1980, many additional buildings have been constructed at Brooks Camp and the other Katmai camps—some by the concessioner, others by the NPS—but they will not be discussed here.

During the 1960s, the NPS became aware of two new camps in the area. As noted above, the Army Air Corps had established two camps near its King Salmon facility during the 1940s: Rapids Camp, along the Naknek River, and Lake Camp, at the western end of Naknek Lake. Facilities at Lake Camp, over the years, grew to include a 16' x 40' Yakutat hut (presumably used as a barracks), two Quonset huts, several corrugated metal shop buildings, a dock, and a building used as a barracks, mess hall, and recreation hall. The camp, therefore, had been developing for more than twenty years when Congress, in January 1969, decided to expand Katmai's boundaries to the westward to include portions of Lake Camp. The monument expansion apparently had no effect on the camp or its activities. When the camp closed, in 1976, the buildings were abandoned. Two years later, on December 2, 1978, most of Lake Camp's buildings were destroyed by fire, apparently in reaction to President Carter's national monument proclamation the day before. The remaining camp buildings have since fallen into varying states of collapse. [11]

The other Katmai-area camp that came to the NPS's attention during the 1960s was Enchanted Lake Lodge, located a mile south of Nonvianuk Lake. In 1964, Edwin Seiler began constructing a lodge complex at Enchanted Lake; he completed two guest buildings in 1965 and a lodge in 1966. By the end of the decade he had also constructed a warehouse and a mile-long road connecting his property to Nonvianuk Lake. Additional structures have arisen on the site since 1970. [12]

In recent years, NPS officials made two decisions that have negatively impacted tourist-oriented buildings in the monument. In 1984, they ordered Katmailand (which was then the park concessioner) to demolish or move the remaining asphalt-shingled cabins at the original Brooks Camp site. They did so because the original camp, situated as it was in the lowlands near the mouth of Brooks River, was subject to periodic flooding and because the site was a primary travel route for the area's brown bear population. Katmailand, in response, demolished some cabins and moved others in 1985 and 1986; as a result, the only two "original" Brooks Camp structures have not only been modified by the addition of asphalt shingling, but they have also been moved.

Historic Property Summary and

Recommendations

As the narrative above has suggested, the first structures in the monument that are related to a tourism theme were constructed in 1950, when NCA officials decided to build five fishing camps in the lake country west of the Aleutian Range. From south to north, these five were Brooks Camp, Coville (later Grosvenor) Camp, Kulik Camp, Nonvianuk Camp, and Battle Lake Camp. The camps, not surprisingly, started modestly; their first structures were either tents or wall tents. Most if not all of these tents were soon replaced with structures featuring asphalt shingling over a wooden frame. By the mid-1950s, however, both the National Park Service and NCA began building wooden structures: the NPS's first structures were crafted from local lumber, while NCA constructed Panabode-style buildings. (By 1962, the NPS was also using the Panabode style in its new Brooks Camp buildings.)

The various camps, therefore, are an amalgam of buildings. Each camp still boasts several asphalt-shingled tents; these are the oldest buildings, but all have been modified from their original wall-tent construction, and in Brooks Camp's case, the two remaining buildings of this style are no longer on their original footings. The second oldest set of buildings, all of which are still standing, are the two log buildings that the NPS built during the 1950s (the ranger station and the boat house, both located at Brooks Camp) and the concessioner's first two wooden buildings (the manager's office at Brooks Camp and Grosvenor Camp, respectively, both in the Panabode style). Next in order of importance, chronologically speaking, are the various buildings that the concessioner built from local lumber at Kulik and Nonvianuk camps, the most prominent being Kulik Lodge; these were built between 1958 and the early 1960s. Buildings erected during the same general time period, but of a different style, include Brooks Lodge, the various guest cabins, and the combination comfort station and bathhouse; these are all of Panabode-style construction. Of final note are the various NPS structures that were built during or slightly after the construction of the Valley Road; these include three employee cabins, a warehouse, and the Three Forks Overlook reception center.

Of this retinue, perhaps the most significant are the NPS's Brooks River Ranger Station (NPS Building No. BR-1, AHRS Site No. XMK-093), which was built in 1955, and the nearby boat storage house (BR-38, XMK-094), which was built circa 1959. They are considered significant because they represent the early period of tourism and park management in Katmai National Monument, and because their Rustic Style of construction hearkens back to styles found in other national park units. For both of these buildings, the National Park Service submitted a report to Alaska's State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), requesting a Determination of Eligibility (DOE) to the National Register of Historic Places. In July 1999, the SHPO responded by agreeing that both buildings were eligible to the National Register under Criterion A. [13] This determination was made despite the fact that during the summer of 1998, an addition to the Ranger Station's east elevation dramatically changed its historic appearance. The modification is, however, considered reversible inasmuch as the original station walls and roof structure remain largely intact.

|

| Kulik Camp during the late 1950s included the lodge and a few tent frames covered with asphalt shingling. Wien Collection, AMHA. |

As the discussion above has shown, the Northern Consolidated Airlines camps erected various styles of buildings between 1950 and the early 1960s. Each of the structures built during this period has the potential for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. It is recommended that the historic buildings in these five camps—constructed by both the concessioner and the National Park Service—be further investigated for National Register eligibility. This investigation should include a field survey, further documentation, and subsequent data evaluation. Because they are manifestations of the early tourism industry in Katmai National Monument, these properties should all be nominated under a tourism theme, although a conservation theme may also be considered for properties erected by the NPS. And because of both historical and architectural similarities, it is recommended that a Multiple Property Documentation Form be employed. Such a form provides a streamlined method for organizing and registering properties, and it facilitates the evaluation of individual properties by comparing them with resources that share similar physical characteristics and historical associations.

Endnotes

1 Frank B. Norris, Tourism in Katmai Country (Anchorage, NPS, 1992), 49.

2 Been, Field Notes of Katmai National Monument Inspection 12, 30-31, 47.

3 Norris, Tourism in Katmai Country, 4.

10 The origin of the name "boat house" is uncertain, as there is little information regarding boats that the NPS used during this period (See Chapter 5). The "boat" being referred to may have been the small craft that staff used to cross Brooks River, or it may have referred to a Mission 66 proposal that would have brought visitors from Brooks Camp to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes via a combination boat service (to the mouth of the Ukak River) and a ten-mile road.

11 Norris, Tourism in Katmai Country, 127-29.

13 Judy Bittner to Deborah Liggett, July 6, 1999, in LAKA cultural resource files.

katm/hrs/chap11.htm

Last Updated: 22-Oct-2002