|

Katmai

Building in an Ashen Land: Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 3:

RUSSIAN AND EARLY AMERICAN INFLUENCE

Russian Period

(1760-1867)

AT THE TIME OF CONTACT with the Russians, the Katmai Native inhabitants were living in settlements along the coast at Katmai and Kukak, and in the interior, northwest of Katmai, around the eastern region of Naknek Lake, at the multi-villages that came to be known as the Savonoski settlements. By the mid-1780s, the Russian fur traders had incorporated the Alaska Peninsula Sugpiat/Alutiiq along Shelikof Strait and, a short time later, the interior Savonoski people into their fur hunting and trading network. The Russian-American Company (RAC) established a hunting and fur trading station at Katmai and constructed several buildings and structures, including a Russian Orthodox chapel. Katmai remained the significant RAC post along the Shelikof Strait coast throughout this period.

Russian Expansion into the Katmai

Region

Beginning in the 1760s, the Russian fur hunters (promyshlenniki) moved eastward from the Aleutians into the Kodiak and upper Alaska Peninsula areas. The Russians were eager to incorporate the Native people, who lived on Kodiak Island and across Shelikof Strait, into their fur hunting and trading activities. The Russians knew little about the area except that the Sugpiat/Alutiiq people, like the Aleutian Islands people, were adept at catching sea otters. The pelts were lucrative trade items in China.

Grigorii I. Shelikhov, fur merchant and partner of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company (a precurser to the Russian-American Company), sought to establish a permanent settlement on Kodiak Island from which he could expand his fur hunting activity and the Russian colonization of America. Beginning in the 1760s, the Kodiak Islanders resisted the Russians through a series of armed conflicts that lasted for twenty years. [1] The Russians pushed ahead to establish posts at Karluk (1785) and Afognak (1786). By 1786, the Russians had subjugated the Native inhabitants into hunting for furs, and continued their expansion into the Alaska Peninsula and southcentral Alaska.

Initially, Russian parties that explored as far as Kamishak Bay in the winter of 1785-1786 reported no difficulties in carrying on their trading activities with the area Natives. [2] In May 1786, Shelikhov wrote to his chief manager about stationing crews across the strait from Kodiak Island on the Alaska Peninsula, "These men should be kept in artels [3] [crews] 20 at Katmak [Katmai] and 11 between Katmak and Kamyshak, closer to Katmak, in the village." The summer settlement of Kukak was most likely the other place to which he referred. [4] It took several years, however, for the Alaska Peninsula artels to be established. Up until the summer of 1791, the area inhabitants had succeeded in keeping the Russians from settling among them. [5] In the meantime, Shelikhov's outfit established Fort Alexandrovsk (1786) on the Kenai Peninsula. Shelikhov's fierce competitor, the Lebedev-Lastochkin fur trading company, established a post on the Kenai Peninsula that same year. Their rivalry resulted in hostilities breaking out on several occasions among the company hunters. Those hostilities involved the Natives who worked and traded with them.

This rivalry intensified until the late 1790s when Aleksandr Baranov, then chief director for the Shelikhov-Golikov Company's American interest, succeeded in overcoming rival Russian traders, notably the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company, for control of the fur trade. In 1789, Shelikhov-Golikov established its headquarters at Kodiak, which became the major fur depot for the region. With its permanent base at Kodiak, the company spread onto the mainland and beyond. In 1799, the Russian Czar, Paul I, authorized a charter that granted monopoly of the American fur trade to the newly formed Russian-American Company (RAC). Baranov later became head of the company and the RAC monopolized the Alaskan fur trade through the end of the Russian period.

The Katmai Artel

The RAC organized hunting crews and workers into artels or into the smaller odinochkas (one man posts). A baidarschchik (crew chief) headed each artel and passed along the manager's orders to their crews. [6] Shelikhov's instructions for constructing buildings and structures to support the artels included,

when possible build the company's buildings according to my plans. They must be made out of logs or in the form of dugouts where there is not enough timber. For native workers and for other natives who might come on business or for a visit, build special yurts [a driftwood hut or dugout dwelling] about 100 sazhen [approx. 700 feet] from the fort and the company's buildings. Always keep a two year supply of local food products in dry barabaras for Russians, native workers and hostages. Have a large and unheated barn in which to keep baidaras, baidarkas and dried fish. Have nets for each work crew, good wooden baidaras, and a supply of lavtaks [skins] for baidarkas. [7]

Katmai was a logical choice for the RAC to set up a post as the nearby Native population provided a source of labor for fur hunting activities. Katmai also had strong trading ties to the upper Naknek Lake area, including the Savonoski villages, and to the Bristol Bay region. [8] In the early 1800s, Davydov noted that "The baidarshchik in Kakmaisk [Katmai] receives by barter animal pelts from the North and from the hinterland of Aliaska." [9]

During the early 1790s, the Russians established a hunting party and trading post at Katmai which was considered an odinochka by 1794. [10] The post was active by 1795, when it was noted that "The hostages from Karluk, taken in pacifying the inhabitants are kept in the Katmai artel in Aliaksa." [11]

The RAC soon expanded Katmai into an artel that was located away from the coast, "up the river, between lakes, on a plain." [12] The RAC established its second artel along the Alaska Peninsula before 1799 at Sutkhum, located on Sutwik Island 130 miles southwest from Katmai. The posts were established because "A good situation, dependable weather, succulent grass and plenty of fish and land and marine animals persuaded Mr. Baranov to establish settlements in two places on Aliaska [Peninsula]." [13] For a length of time, Katmai reflected the type of buildings and structures constructed in some of the Kodiak artels. This was part of Shelikhov's plan to create an agricultural base in the region, as well as to gather furs. As an 1821 description makes clear,

Katmai artel on the south coast of the Alaska Peninsula. Two Russians. Rather good buildings: a house, barracks, warehouse, shop, barns, etc. Over 20 head of cattle. They did some fishing ("they prepared fish"), trapped sea otters, and bought from the natives furs of river beavers, foxes, deer, bears [14]

By the 1830s, the Katmai and Sutkhum posts were downsized. As Khlebnikov noted,

Cattle raising was established successfully in the Katmai artel, but it has been reduced due to a shortage of men. There are very many red foxes of very good quality. There are natives only near the Katmai artel. Company buildings in both places were originally extensive, but are now dilapidated...the following are on company maintenance: in Katmai - one Russian; in the two combined = Aleuts 10 males and two females and one Russian released from service. [15]

Other Settlements and Places

Throughout the Russian period and for several decades of the American period, settlements continued along the coast at Katmai, Kukak, and in the interior at Savonoski. There were additional settlements and seasonal camps, as has been indicated by documented visits, surveys, maps and the Alaska Russian Orthodox Church records.

The Russians continually sought out new sites as quickly as they depleted the fur resources. In 1786 Shelikhov instructed his chief manager at Kodiak to gather information about locations, resources, people, settlements, and Native place names in the region including the upper Alaska Peninsula. [16] The Russian hunters gained first hand experience about the Alaska Peninsula through hunting and trading expeditions. Decades later, trained Russian naval officers supplied accurate charts and maps.

During the 1780s, the Katmai coast received few non-Russian visitors. In 1786, however, Captain John Meares in his British trading ship Nootka sailed through Shelikof Strait. This voyage recorded new geographical knowledge about the area, including the fact that Kodiak Island was separated from the mainland by the strait. Meares also documented Russian fur trading taking place around Amalik Bay or Kaflia Bay. In this area, Meares' ship was met by a Russian in a canoe who told him that the Russians were established on Kodiak Island. [17]

During the 1790s, Baranov sent out various detachments of promyshlenniks on exploring ventures. One, the Medvednikov-Kashevarov 1797 expedition, confirmed the location of Iliamna Lake and the various portage routes across the Alaska Peninsula. [18] The Lebedev-Lastochkin Company, however, was already familiar with the area, having established an artel at Iliamna. [19]

The first map that combined the earliest Russian knowledge about the upper Alaska Peninsula is dated 1802. The map shows Katmai along with an illegible name at the location marked on modern maps as Kaguyak. [20]

Kukak Village, although not identified on the above map, was known by the Russians and singled out in the 1795 and 1804 censuses. [21] In 1806, the first ship stopped at Kukak Bay's "inner" harbor. Dr. Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, a German physician and naturalist with Rezanov's voyage, visited inhabitants from the "Village of Toujajak." Although it is not clear if "Toujajak" was Kukak Village or a separate seasonal camp, Langsdorff provided a description of his visit to the "native summer huts" located on the northeastern shore of the bay:

The inhabitants gave us a very friendly reception in their small earthen-covered hut with grass growing all over the outside and an entrance that was so low and narrow that we could only crawl in hunched over. Everyone sat around a fire burning in the middle of the hut. A kettle of fish was hanging over it. Several small salmon, spitted upon sticks stuck in the earth around the fire, were being roasted.Opposite the door, the floor was covered with fine, dry wood shavings and several clean seal skins, where we were asked to sit. [22]

By the early 1800s, the RAC sent expeditions across the Aleutian Range and into the interior. The Savonoski people, who lived in the multivillage community located just east of Naknek Lake, were in contact with the Russian traders at least by 1807, when a marriage was registered that year for a Russian promyshlennyi from the "Severnovskoe settlement." [23]

|

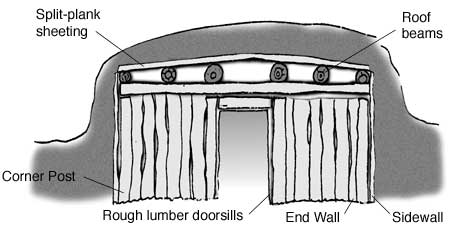

| Above: Sketch of shoreline with sea otters by Georg Langsdorff, ca. 1805. As part of Rezanov's voyage, Langsdorff visited Kukak Bay inhabitants in 1806. Bancroft Library. |

The Savonoski people also had several seasonal camps in the area, as twentieth century archeological investigations show habitation sites used at least seasonally during the Russian period near Savonoski River, Grosvenor, and Coville lakes as well as at Brooks River. Most of these sites continued to be used in the Early American period, some even after the 1912 volcanic eruption. [24]

Petr Korsakovskiy's 1818 expedition, from Kodiak to Katmai, across the Alaska Peninsula and into the Iliamna region, highlighted the RAC's need for information about Alaska's southwest interior. Korsakovskiy's expedition resulted in the RAC establishing Alexandrovski Redoubt (1818-1846) at the mouth of the Nushagak River. During the Russian time period, the Aglurmiut village of Paugvik, located at the mouth of the Naknek River, was the primary settlement in the area. [25]

In 1818, the RAC's Katmai jurisdiction probably included six settlements located on the upper Alaska Peninsula: two Savonoski settlements, Katmai, Kukak, Naushkak and Ugashek (the latter located over 100 miles southwest of Katmai and outside of today's park boundaries). The Katmai jurisdiction inventory for that year listed a total population of 837 people. [26] Little is known about Naushkak: the settlement is mentioned in the Alaska Russian Orthodox Church Records, it was located north of Kukak (possibly near Cape Nukshak) and it is believed to have been occupied on a permanent or seasonal basis into the 1850s. [27]

Between 1827 and 1836 the shoreline of the entire Alaska Peninsula was carefully surveyed. Ivan F. Vasiliev's 1831-32 surveys charted the coast from Cape Douglas south to Chignik Bay. From these surveys, Vasiliev reported the Native designation "Kukak" for an "Eskimo" village located four miles southwest of Langsdorff's "Toujajak Village." Vasiliev also provided the name "Kaflia" and reported the name "Akulogak" for Naknek Lake. [28]

In 1827 Captain A.J. von Krusenstern did not personally visit the Katmai region, but he compiled names from other maps that included "Katmay" (Katmai), "Baie Katmay (Katmai Bay), "P[orte] Aiou (Hallo Bay), C[ap] Noughchack (Cape Nukshak), and C[ap] Ighiack (Cape Ugyak). Captain Feodor Petroviche Lutke's 1836 chart included place names of "Kaiayakak" (Kaguyak) and Swikshak Bay, as well as Naknek Lake and Naknek River. [29]

Changes Brought to the Katmai

Settlements

The Russian-American Company's fur hunting and trading practices and the Russian Orthodox Church's (ROC) mission activities brought different influences to the Katmai region inhabitants. The RAC initially incorporated the Native people into their fur trading activities primarily through coercive means. The Sugpiat/Alutiiq people were considered "dependent" and had to work directly for the RAC in the sea otter hunting and trading activities. The promyshlenniki used the same methods of conscripting labor and holding hostages as they had with the Aleutian people to force the Sugpiat/Alutiiq to gather the sea otter furs. The Savonoski people had less contact and were considered "semi-dependent," meaning that their relationship with the Russians traders was more independent. [30]

As part of the Russian system's relationship with its "dependents", the RAC selected community leaders called toions from among the Sugpiat/Alutiiq. The toions had limited authority over certain community and public matters and were expected to be good examples in living their lives according to the ROC dictates. [31] The RAC also required dependents to get permission to visit neighboring islands, thereby controlling the movement of the coastal Katmai people throughout this time.

The RAC Kodiak District organized, provided provisions of food, clothing, and boats, and sent out large sea otter hunting parties during the summer. Under the eye of the Russian overseer, groups of hunters dispersed to their assigned hunting areas where they established base camps and set up temporary shelters of driftwood to store their food and equipment. In a traditional hunting process, the hunters worked together using their baidarkas to encircle the sea otter and used their dart weapons to kill it. The Sugpiat/Alutiiq hunters were part of the sea otter hunting parties that operated along the coast from Kamishak Bay to the Sutkhum odinochka (at or near Sutwik Island). [32] They also joined up with larger contingents, such as the 1805 trek to Nuchek. Some were taken as far away as Sitka, and a few all the way to present-day Fort Ross in California. [33]

The Russian Orthodox Church was the other influential, and to some degree, stabilizing factor in the lives of the Native people. In 1794 the first ROC missionaries arrived and began baptizing the Alutiiq people on Kodiak Island. Within two years, the first church was built on Kodiak and the missionaries took their religious activities to the Alaska Peninsula, Aleutians, Kenai Peninsula and Yakutat. During the winter of 1797, it was noted that ".Aliaksans came to Kadiak and were baptized." [34] During the first half of the 1800s, the ROC Kodiak parish included the Shelikof Strait and Savonoski settlements.

Certain individuals, including the missionaries, criticized the RAC for its ill treatment of the Native people, which included the practice of taking hunters far away from their homes, and the subsequent depopulation. Langsdorff noted in his 1806 visit to the Kukak area,

most of the young people having been carried away to Sitcha [Sitka] to hunt sea-otters. Of a thousand men who formerly lived in this spot, scarcely more than forty remained, and the whole peninsula of Alaksa they said was depopulated in the same proportion. [35]

The system of forcing Natives into hunting relaxed somewhat after 1818 when Baranov left and new management policies were instituted. The early RAC administration had also often come into conflict with the ROC mission. Greater support for the ROC activities was mandated in the RAC company charters of 1821 and 1844, including provisions that required the company to provide full economic assistance and support to the Church. [36]

Conditions for the Native people at Kodiak do not appear to have improved by the 1830s at which time Ferdinand Wrangell (Chief Manager of RAC from 1830 to 1835) made these observations at Kodiak, which can probably be applied for the Alaska Peninsula,

From spring to autumn all the men able to work are sent off by the company to hunt sea otters and birds. From the autumn until spring they are occupied in land hunting fox and otter, and although this measure is essential for the survival of the company, the islanders gain little through this. By excessively low prices paid them for their produce and fairly high prices for the goods in which they are paid, they are unable to clothe themselves and their families with what is absolutely necessary. they are obliged to purchase both their parkas and kamleias from the company or else earn them in some other way. [37]

Throughout the 1800s, the Katmai villages experienced depopulation as did other settlements throughout the region. Below are population figures to give an idea of changes that occurred during the Russian period. [38]

1792 On Alaska Peninsula 814 (439 M; 375 F) 1800 On Alaska Peninsula 209 (119 M; 90 F) 1818 Katmai Jurisdiction 837 (386 M; 451 F) (the jurisdiction probably included these six settlements: two at Savonoski plus Katmai, Kukak, Naushkak, and Ugashek) 1821 On Alaska Peninsula 838 (386 M; 452 F) 1825 On Alaska Peninsula 190 (99 M; 91 F) 1861 Katmai 239 (222 "Aleut"; 17 creole) (this figure may be for the Katmai jurisdiction)

Additional figures for the Savonoski settlements [39], comes from the Alaska Russian Orthodox Church records:

1850 99 (48 M; 51 F) 1861 98

Population loss can be attributed to the extreme hunting conditions, subsequent family and community hardships, hunting accidents, and the numerous epidemics that occurred on both sides of the Aleutian Range. Respiratory epidemics occurred throughout Alaska during the 1800s including the Kodiak area. The devastating smallpox epidemic of 1835-1840 reached the Shelikof Strait settlements during 1837-38. Some success at stopping the epidemic was achieved on the Alaska Peninsula by the Katmai baidarschchik Ivan Kostylev. Kostylev and two others managed to vaccinate 243 people from the villages, all of whom survived; 27 people, the ones who had refused to be vaccinated, died. [40] During the years of 1853, 1860, 1859, and 1863 coughing and respiratory epidemics were reported for villages around Naknek Lake. [41]

Following the losses brought on by the epidemics, the Russian-American Company Chief Manager and governor of Russian America, Arvid A. Etholen, consolidated villages on Kodiak Island during the early 1840s. This activity did not occur along the Katmai coast unless it happened on an informal basis. Katmai continued to be the primary fur trading post and population center on the Alaska Peninsula into the early American period. In 1845, the Russians identified Katmai as one of five depots in the Kodiak district for stocking supplies for hunting parties and for trade. [42]

Northeast of Katmai along the coast, Kukak and Naushkak were occupied to at least 1843. These settlements, however, may have been remnant populations following the smallpox epidemic. Since there is so little mention of Naushkak and Kukak in the historical records, it is likely that these places were used on an intermittent, seasonal basis through the Russian period. [43]

The Russian-American Company Builds the First

Chapel

The only chapel built on the upper Alaska Peninsula during the Russian period was at Katmai. In 1843, RAC manager Ioann Kostylev built the first chapel. This building was replaced with a new chapel eleven years later. [44]

The RAC Chief Manager Etolin provided instructions about the settlements building chapels:

To Toion who are to become starshinas [elders/church readers] in Aleut settlements in the Kodiak Department. The starshina must be firm in having the Aleut men and women fulfill their Christian obligations and carry out all tasks assigned to them by the priest. Toward this end, each settlement is to try to build a chapel, through its own effort, where the priest can conduct worship services when he visits. They should build the chapel when time and circumstances permit, after the settlement has been organized and put into order. [45]

Russian Orthodox Church activities continued with at least periodic visits to Katmai and Savonoski settlements during the 1840s. At Savonoski, the priest would hold services in a tent, as a chapel was not built there until 1877. During 1841 the Kodiak mission recorded a visit to the peninsula with 57 baptisms at Katmai and 46 baptisms in the Savonoski settlements. [46] In the early 1840s, the ROC reorganized its Kodiak Mission, creating the Nushagak and Kenai missions. In 1844 the Savonoski settlements and records were transferred to the Nushagak mission, where a small chapel had been constructed in 1832 and its first missionary assigned in 1842. [47] The Savonoski settlements continued to be served by the Nushagak mission until 1912. The Shelikof Strait villages remained under the Kodiak Mission until they were transferred to the Afognak Mission in 1896.

Early American Influence

(1867-1912)

This time span begins when the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia and ends when the Novarupta Volcano erupted and forced the inhabitants to relocate away from the Katmai area. For the greater part of this 45 year period, the Savonoski, Katmai and Kukak settlements continued with additional settlements at Douglas (identified on modern maps as Kaguyak), and later at Kaflia. The fur trade continued to be the primary economic activity with the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC) becoming the dominant trader in the region. An ACC store was maintained at Katmai with new stores established at Douglas and for a short time at Kukak. The Katmai store continued a brisk fur trade with the interior Savonoski villages. Fur hunters established seasonal camps from Cape Douglas north to Kamishak Bay. The Russian Orthodox Church influence continued within the settlements through visitations by priests and the establishment of chapels at Savonoski, Katmai, Douglas, and Kukak. As the fur trade began to wane in the 1880s, the Katmai inhabitants became more involved with the rapidly growing commercial fishing industry. At the time of the volcanic eruption, many of the Savonoski residents were living in the Naknek area for the summer fishing, and the Katmai and Douglas villagers were fishing at Kaflia, which was the site of a saltery and store.

|

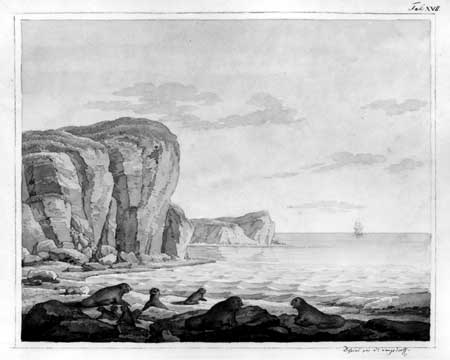

| Above: The Alaska Commercial Company's Kukak Station ledger dated April 1, 1888. This store operated for two years during the 1880s. UAF, ACC Douglas Station records, Box 4. |

Main Settlements

During this period, there was continuous occupation of settlements at Savonoski [48], Katmai, and Douglas, marked "Kaguyak" on modern maps. [49] Kukak was occupied, although it may not have been continuously, until the later 1890s when the population moved to Douglas. The houses continued to be semi-subterranean barabaras, and community houses or kazhims were known to be at Savonoski and Douglas. [50] The largest number of barabaras noted in the literature for Katmai is 20 houses with 218 inhabitants during 1880, and Douglas with ten barabaras and 45 residents in 1901. [51]

The Alaska Native pre-contact barabaras were modified during the Russian period. Early on, the promyshlenniki had adapted the Aleutian Islanders' barabaras by building the sod-covered and arched-roofed structures above ground and by placing a doorway in a wall instead of through the roof. As a result, Natives began changing their house entrances from the top to the wall. By 1870 some of the Aleutian turf-covered dwellings had glass windows, interior plank walls covered with paper, floors covered with dried grass, and small stoves. [52] The Shelikof Strait post-contact houses usually contained two rooms. [53] One such house was noted by the Fifth Earl of Lonsdale during his Arctic journey which took him through Katmai in 1889.

...Mr. Farmin [Fomin] received us most kindly,. He is a Russian Creole, & the maners of a little French man, fussy & quick but very kind. He at once gave me his room in a two roomed turf & log biraba, & so we are dry & comfortable. This is a very small village only about 15 houses & 35 grown up people. [54]

To the north of Katmai, 1953 archeological investigations noted some changes during the historic time at Savonoski. The early, probably prehistoric, dwellings had multiple-roomed patterns. The nearby semi-subterranean structures that contained European artifacts, however, were one-roomed. The framework of the historic houses included walls of split cottonwood and the use of spruce poles for additional support of the sod. Behind the row of houses, there were several wooden storage houses elevated on pilings similar to those found throughout the Bristol Bay region. [55]

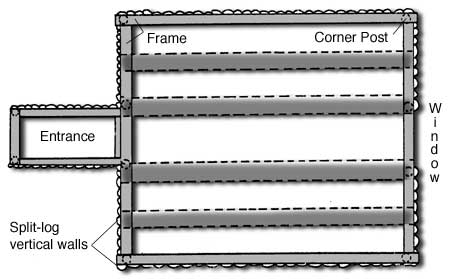

|

A. Plan View

B. Interior View, North Wall

|

| Modern Semi-Subterranean House Structure, Savonoski. Adapted by FMB from W.A. Davis, Archaeological Investigation (1954) |

Kazhims existed at Savonoski, Douglas, and probably Katmai. The Douglas community house, investigated in 1953, was built underground except for the roof. Hand hewn lumber was used to build the large oval room with a sloping passageway entrance. Archeologist Wilbur Davis interviewed a former Savonoski resident who reported that "the people danced, held the November festival, and played the stick gambling game, "gathak", in the kazim at Old Savonoski." [56]

Alaska Commercial Company Establishes Trading

Stores

Hutchinson, Kohl & Company emerged as the commercial successor to the Russian-American Company and took over the Katmai trading station around 1868. There soon emerged a second firm, the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC), that assumed control over the Alaska operations and assets of Hutchinson, Kohl & Company in 1870. The ACC's Kodiak District took over the former Russian trading posts along the Alaska Peninsula and Cook Inlet regions. [57]

By 1872 the ACC was operating the Katmai post, which continued to be the major coastal post for at least a few years. [58] While barabaras were better suited for the climate, the ACC found ways to maintain a log or wood frame store, as this 1890 description noted:

The village, consisting of sod huts surrounding the "store" and a small log chapel, was built upon a swampy flat along the banks of a salmon stream. The summer visitor is impressed with an idea of what winter must mean in this desolate spot when he notices the heavy chains and ropes which are laid over the roof of the trading store and securely anchored in the ground as protection against the furious gales that sweep down the steep mountain sides but a few miles beyond. [59]

In 1878 the Alaska Commercial Company opened its second post along the Katmai coast at Douglas. At this time, the Native village was already at the site, with a Russian Orthodox chapel built 1875 or 1876, and the Shirpser, Haritonoff and Company had already established a rival fur trading post there as well. [60] Shirpser, Haritonoff and Company sold or reorganized into the Western Fur and Trading Company in 1879. This company continued to operate its Douglas Station for the next four years and also maintained a post at Iliamna. [61] In 1883 the Alaska Commercial Company eliminated its primary competition by purchasing the Western Fur and Trading Company. [62]

While the ACC maintained at post at Katmai, Douglas became the significant sea otter hunting center along the coast. In 1880, Ivan Petroff, observed that "Katmai was once the centre of all the peninsula trade, and the point of transit for supplies to Bristol Bay, and on through Nushegak and Kolmakoosky. Its former glory has departed; it has been superseded by a rival in the north at Cape Douglass, as far as trade and traffic in furs is concerned." There was only one settlement of any significance north of Kukak along the Katmai coast. "A village of 46 persons. two trading stores, a chapel, seven barabaras and it was the terminus of a portage to Bristol Bay." [63]

The Douglas Station's merchandise inventories included: staples of rice, lard, pilot bread, bacon, sugar and tea, and equipment items such as baidarka and dory, seal gut, spades, hammers, fish nets and hooks, rifles, and mouse and fox traps. Clothing and shoes for men, women and children were listed with items such as dress goods, gingham, red flannel, chinchilla caps, and woolen shirts and socks. Housing items included pots and pans, kettles, crockery, lamps, and seal oil. There was also a mix of holy pictures and church candles, children toys, alarms clocks, thermometers, cigarettes, playing cards, and musical instruments such as autophone organs, an accordion as well as guitar strings. [64]

On October 14, 1886 the ACC Douglas Station agent went to Kukak and opened a store there. This was a relatively short trip as Kukak was only six hours by baidarka from Douglas in good weather. [65] The Douglas Station agent was also in charge of the Kukak stock. In October 1887 the agent "went to Kukak took stock and Brought what I could from there as the goods was getting damage from wet weather also made the windows good & fast." [66]

By 1896 the ACC Douglas Station included a house, a store, and a new shed. Some of the building materials used are found in the Douglas Station accounts and include charges for: pine, shingles, house frame, and putting up the frame. A 1890 invoice was for a new house at Douglas that included "200 Afognack boards, nails...white paint, iron hinges, 1 sheet tin, 2 window glasses, 3 chimney clay pipes, shingles, moss, clay and stone and labor. The house interior included wallpaper described as "prints clothed on House walls." [67]

The ACC controlled the Katmai area fur trade through most of the late nineteenth century, maintaining stores at Kukak until 1888, Douglas until 1901, and Katmai until 1903.

Several Chapels are Built

After the American purchase of Alaska, the Katmai region's inhabitants continued to be influenced by the Russian Orthodox Church, which retained its Alaska property and the right to continue its activities according to the Treaty of the sale of Alaska. [68] During this time period, ROC chapels were built north of the Aleutian Range at the Savonoski settlements (two chapels) and along the coast at Katmai, (one rebuilt and one new chapel), Douglas (two chapels), and Kukak (one chapel). [69]

|

| The last church built at Savonoski, 1918. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 4, 6389. |

Initially, the ROC reduced its number of clergymen and withdrew the Nushagak priest. Within ten years a priest was reassigned to Nushagak. [70] The Savonoski settlements received regular visits from the Nushagak priest and continued to be under the mission's influence until 1912. [71] At Savonoski, located on the east end of the Iliuk Arm portion of Naknek Lake, the first chapel named for Our Lady of Kazan' was built in 1877. Another chapel was built at the second Severnovskoe settlement (Kanigm'iut) in 1902, named for Nikolai the Miracleworker. [72] The Shelikof Strait coastal villages were under the parish of the Church of the Resurrection at Kodiak until 1896 when these settlements were transferred to the Afognak parish. [73]

When possible, annual visits were made by a priest to hold church services, perform baptisms, chrizmations, and marriages in the coastal settlements. The 1898 visiting priest noted the difficulty in communicating with the Alaska Peninsula settlements "since it is necessary to cross the numerous bays along the very stormy Shelikof Strait in baidarkas." [74] The Alaska Commercial Company Douglas Station manager noted the priest's arrivals and departures:

Aug. 15 1885... for 3 days of service; when priest left, Bydarkas left for Katmia & Kogok [Kukak]; Monday August 15 [1887] ...The Priest arrived during day from Wrangell [on the Alaska Peninsula] via Katmia & Kukak with 3 Bydardas to hold church Service with the People here...3 days of services; Friday priest crossed the Straits and The Katmia People left here for home; "August 25th [1888] ... The priest arrived from Katmai to hold church service. [75]

The early chapels were modest buildings:

The outlying chapels in the Kodiak parish were served by lay readers and usually built of logs. "In outward appearance these chapels are not attractive," wrote a government official, "But many of them are quite tastefully decorated in the interior, and in all of them the greatest neatness is preserved. ["76]

Katmai's second Orthodox chapel was built in 1854 (the Russian-American Company built the first chapel in 1843). Renovations occurred in 1884, but the wind seriously damaged the chapel in 1886, which required its rebuilding in 1887 (designated as the third chapel). [77] The 1890 census noted this building as a small log chapel. During his 1895 visit, the Kodiak priest, Tikhon Shalamov, described the chapel as "not new...with a small cupola that is painted with white paint, the roof is shingle, spacious, the interior has wallpaper. It has many icons." [78] Six years later, the visiting Afognak priest, Fr. Vasilii Martysh, noted,

The chapel is rather spacious and is kept clean and in exemplary order, owing to the care of the sexton. Though it was built not very long ago, it is rotted underneath. Under the direction of this sexton the inhabitants have set to building a new chapel. The materials for it have been prepared in part from a steamer broken up near Katmai, part purchased from the company. [79]

At Douglas, the first ROC chapel was built in 1875 or 1876. The ACC Douglas Station manager, Vladimir Stafeev, began building a second chapel in 1890. It appears that some of the lumber from the first chapel was used to complete the second chapel. It was consecrated the following year. During 1893, a porch was added, the iconostasis was rebuilt, the inside was wallpapered, and construction on the bell tower began. [80] In 1901, the visiting priest noted that the Alaska Commercial Company had built the small chapel and provided some bells. [81]

Kukak had at least one ROC chapel that was built sometime after the 1880 census and but prior to January 1890. The first mention of this chapel in the church records is New Year's Eve 1889/New Year's Day 1890 after a windstorm had destroyed it. [82]

Windstorms wreaked havoc on the coastal chapels, but one such storm provided materials for building two new chapels. In June 1898 the Western Star, part of the Moran Fleet that was heading for the Yukon, was beached and wrecked at Katmai Bay. The salvaged wood was used in part to build chapels at Katmai and Douglas. [83] One of the Moran fleet crew's journal entry for July 1898 noted a visit to Katmai village and the dual role of the local ACC manager:

Last night three of us visited the Katmai Indian village, it sits on the river a short distance above the point where the water spreads out over the wide flats of the lagoon, and is similar to many others along the shores of Alaska. Alexander J. Petelin, who was born in this part of the world, his father a Russian, his mother an Aleut, fills the dual capacity here as agent and store-keeper for the Alaska Commercial Company, he also officiates in the Greek church services, in a building occupied as a chapel. He said he had never been ordained as a priest, but had been educated as such. He speaks the Indian language and preaches to them at times in their own tongue. [84]

|

| Above: Katmai's last chapel, built prior to 1912 volcanic eruption. 1915 photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 1, 3635. |

Population Ties and Movement

Through most of the early American period, settlements continued at Katmai, Savonoski, and the Douglas and Kukak areas. Katmai maintained the largest population center along the coast. By 1880, Katmai's population was 218. That same census year, Savonoski had the second largest population with 162 people, and the combined Douglas and Kukak population was 83. [85] Katmai continued its trading business with the Savonoski villages and Bristol Bay. [86] The definite preference by the two Savonoski settlements, to continue trading with Katmai instead of taking the easier Naknek River route to Paugvik, lasted at least through the 1880s. Katmai and Savonoski inhabitants also had ties with the Douglas populace. Although it is not clear when the settlement was first inhabited, a ROC priest noted that, "Douglas Village was formed in part by the inhabitants from Katmai and in part from Severnovski." [87] Douglas was also located at the end of an established route to Bristol Bay. The Katmai villagers traveled to Kukak as noted in 1880, when Petroff described the Kukak residents as "sea-otter adjuncts and contingents of the Katmai people." This statement indicated that the Katmai people were occupying the area at least on a seasonal basis. [88]

During the 1880s, some of the Katmai residents were known to have traveled southwest along and across the Alaska Peninsula to hunt and trade. Katmai villagers were noted in the ACC Wide Bay station account books and also traded at the seasonal Sutkhum store. After 1867 people were free to move about and to resettle in old village sites. It is likely that a few Katmai villagers moved down the coast to Wrangell. [89] Both Savonoski and Katmai residents traveled to the Cold [Puale] Bay store, located 35 miles southwest of Katmai, as well as to Kanatak, Becharof Lake, Egegik and to Naknek, at least by the early 1900s. [90] People also moved into Katmai; the 1890 census noted that of Katmai's 132 inhabitants, 51 people were not born there, but had moved from somewhere else. [91]

Seasonal Camps

Several seasonal camps and other habitation sites were used at least intermittently by the Sugpiat/Alutiiq and the Savonoski people during the Russian and Early American time periods. Most sites were located around the Naknek Lake drainage and along the Shelikof Strait side of the peninsula.

Seasonal caribou and or fishing camps were located around the Naknek Lake drainage in the Savonoski River, Lake Grosvenor, Lake Coville, and Brooks River areas. Archaeological investigation showed that at least one house excavated by Brooks River might have been used during the winter. [92] Ukak was another traditional hunting and fishing camp used by the Savonoski people up until 1912. This camp was located up the valley of the Ukak River near the foot of Mount Katmai. [93]

Seasonal camps and other habitation sites were located along the Katmai coast and used, at least on an intermittent basis, during the Russian and American periods. For the most part, the exact location of these sites is not known and little archaeological investigation has been done.

During the end of the early American period, if not earlier, Savonoski people were traveling to the coast via the Hallo Bay or Douglas pass routes. One of their camps was located on the north shore of Hallo Bay. [94]

Single barabaras were noted during the 1901 Afognak priest's visit to Douglas. The ship crossed the strait and anchored at Hallo Bay (eight miles from Douglas), then moved closer to Douglas, which was located in a small bay. "Here near a small river stands the lone barabara of the Aleut Petr Anignan who speaks Russian rather well. Having rested in his barabara and drunk tea, we set off farther in the baidarkasin the evening we safely arrived at Douglas and stopped in the barabara of the Aleut Inokentii." [95]

Although Russian and early American maps identified a settlement with various names (including "Kayayak" and its variants) at Swikshak Lagoon, this was most likely a seasonal camp. [96] According to Katherine Arndt, there was probably a continuous seasonal occupation of one or more sites here during the Russian and early American periods. According to the ACC Douglas station manager Stafeev's log books from 1889-1895, the Douglas people had a summer camp, that included barabaras, called "Pahliak" at the locality of Swikshak. [97]

The vicinity of Dakavak Bay, Amalik Bay, Takli Island, and Cape Atushagvik was probably used throughout this period at least on a seasonal basis. This was the closest point of land from which people would travel in boats across Shelikov Strait to reach Kodiak Island. Structures are probably located in the area, as people often had to wait several days or weeks before weather was calm enough to allow for crossing the Strait. [98]

During 1895, the Kodiak priest on his travel from Katmai north by baidarkas noted two or three barabaras at "Togaly Bay" (possibly Dakavak Bay), where the Katmai people gathered in the summer to dry humpback salmon. Four hours from that location, they "landed on a tide flat to drink tea and have lunch in a little place called Attushalvik [possibly Cape Atushagvik]. This is the narrowest place in Shelikof Strait [30 miles]. From here in baidarkas they usually cross it." [99]

Hunting Parties and the Declining Fur

Trade

The Alaska Commercial Company organized hunting parties similar to the Russian-American Company by provisioning the hunters and providing baidaras to transport them and their kayaks to the hunting areas. The height of the fur trade was 1885 and the number of sea otters rapidly declined after this time. [100]

During the late 1880s, the ACC Douglas Station agent, John W. Smith, noted the arrival of men from Katmai and Kukak to form hunting parties. A January 1887 entry by the station manager noted that he was "getting the parties ready to hunt had a good talk with the People about hunting and the AC [Alaska Commercial Company]." Other journal entries noted people arriving from "Kamashak" on foot to trade and several Bristol Bay people, including some with bidarkas on sleds, to hunt from Douglas. Hunters also tried to get to a place name Reglarawak (later spelled Rreglarawak), which the store manager later visited and arrived back to Douglas within two days. [101]

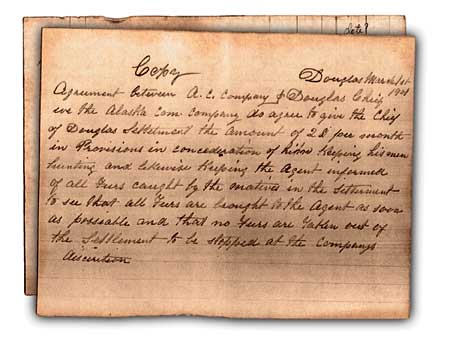

|

| Above: Copy of March 1, 1901 drafted agreement between the Douglas Chief and the Alaska Commercial Company, Douglas Station Manager. If signed, the Douglas Chief agreed to keep his men hunting for furs and to turn all furs gathered by the villagers over to the Douglas Store in return for provisions. Due to the demise of the sea otters, the Douglas store closed that summer. UAF, ACC Douglas Station records, Box 5 folder 66. |

Kamishak Bay was an important hunting region. During the 1880s and 1890s, Bristol Bay area Natives migrated each spring to the area to hunt sea otter for the ACC Nushagak agent John W. Clark. Many camps were spread out along the shores from Augustine Island south to Cape Douglas. The hunters took the seal and otter pelts to the ACC Fort Alexander warehouse. [102] From 1883 to 1893, the ACC Iliamna Station supplied a party that hunted sea otters in Kamishak Bay. [103]

Hunters were also known to occupy nearby islands. Afognak sea otter parties hunted on Shaw Island and "Ikuk Islet;" the latter was probably one of the Shakun Islets. [104] The 1890 census noted,

Small camps of otter hunters exist on the low, barren islands near the southern shore [of Kamishak Bay]. Low structures of rocks, canvas, and drift logs are anchored with chains and cables to the rocky surface, to prevent them from being swept away before the constant gales: and here the hunter watches for weeks and months, bereft of all comforts, unable to stand erect within his lowly dwelling, while the force of the wind prevents him from doing so outside, waiting for a day's or even a few hours' lull between storms to visit his nets or to shoot sea otter from his boat. [105]

Schooners traveled around the Cook Inlet and other stations. They arrived at the Douglas station to deliver goods and to pick up the furs. Sometimes they brought in or picked up hunting parties. This might have occurred more often as the hunters had to range farther for the disappearing sea otters.

Most likely the decline of sea otters caused the ACC to close its Kukak store in 1888. By 1890, the Eleventh Census taker note that the Douglas station otter trade had significantly declined:

The only settlements in the vicinity of Cape Douglas consist of a small trading post, with a few native houses, and the village Kukak, with less than 100 inhabitants of the Kadiak Eskimo tribe. Formerly this vicinity was looked upon as one of the most important sea-otter hunting grounds, but of late years the trade in these valuable skins at Douglas station has become insignificant, and the natives are obliged to seek distant hunting grounds with the assistance of the traders. The natural food supply of these people is quite abundant. The sea teems with codfish and halibut, the streams with salmon, and hair seal are plentiful along the shore during the winter. [106]

This same census noted fewer than 200 people living at Katmai, with a continuing orientation to the sea, and habit of purchasing goods at the trading store:

The settlement of Katmai , and its population, consisting of less than 200, depend upon the sea otter alone for existence. The men could have reindeer in plenty by climbing the mountains that rear their snow-covered summits immediately behind them, but they prefer to brave the dangers of the deep and to put up with all the discomfort and inconvenience connected with sea-otter hunting, and in case of success purchase canned meats and fruit from the trading-store. [107]

The poor economic conditions and epidemics led to further depopulation in the Katmai region. An epidemic in the Douglas area occurred in May 1888, when the ACC Douglas Station agent noted that the people were all sick and that one baidarka arrived from Kukak to take medicine back. By June, a total of 18 people had died. [108] The Kodiak priest, in his 1895 visit to the Alaska Peninsula settlements, stopped at Puale Bay (then called Cold Bay) and noted the barabaras used by Katmai inhabitants during the summer sea otter hunts, "Now, none of the inhabitants could be found. Here, as in all the bays of Alaska, there are burial mounds and crosses, under which lie the poor and much-grieved bones of Aleuts." [109] Another priest visit noted accounts of starvation during the winter of 1897-98 at Douglas and other settlements. [110]

In 1890 the Douglas area consisted of "one trading post, a chapel, and a few native houses...the inhabitants who, together with those of Kukak, numbered 85." During 1895, the priest tried to visit Kukak Village but he discovered that the inhabitants had moved to Douglas. Travelers between Douglas and Katmai, however, continued to use Kukak as a rest stop and hunters out of Douglas camped there as well. [111]

By 1890, Katmai included "132 inhabitants making up 37 families and occupying 17 houses.all but one white man were Kodiak Eskimo. ["112] At Savonoski for that year, the population was 94 (47 men; 47 women). The Russian Orthodox Church continued to be an integral part of the Katmai settlements, and the chapels at Savonoski, Katmai, and Douglas were active until 1912. Part of the mission activities included education, which appeared to be going on in the Katmai settlements to varying degrees. In 1900, Savonoski was listed as having a primary school. [113] At Douglas, education took place on a more informal basis with the ACC manager at Douglas, Vladimir Stafeev, noting in 1892 that someone from each household could read and write. [114]

In August 1901, the ACC closed the Douglas store. The priest who visited the settlement a few weeks later believed that the store closure was going to be a hardship for the people. The following year, however, the priest noted that no deaths had occurred among the population of 55 and that the people had returned to their original food. [115]

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Katmai experienced an influx of winter travelers who were using the Katmai Pass route to get to the Nome gold fields. To accommodate these prospectors, the local trader built a "Bunk House" located away from the village. [116] In 1903 the Katmai store closed. [117] The ACC planned to sell the posts and assessed one building at Douglas at $25.00 in 1906. That same year, the ACC trading store at Katmai was offered to Omar J. Humphrey for $150.00, although the sale did not take place. [118]

|

| Above: Katmai village log and frame buildings, one of these may have been the Alaska Commercial Company trading store. Photographed by the National Geographic Society expedition members in July 1915, after the flood. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 1, 3944. |

Population Gravitates to Commercial Fishing

Industry

By the late 1800s, the economic focus was shifting away from fur hunting and trading activities and towards the rising commercial fishing industry. The trading posts were closing and sea otter hunting was prohibited by law in 1911.

The population at Savonoski in 1900 was 100 and ten years later there were 74 people. [119] At the time of the 1912 volcanic eruption, two families were living at Savonoski, with the rest having moved to the mouth of the Naknek River looking for employment in the fishery. [120] At that time, Savonoski consisted of fifteen sod covered barabaras with several rough hewn log caches, one log chapel that was dedicated to St. Mary, and Mrs. Palakia Melgenak's store. American Pete, the chief of Savonoski village, was using his houses at both Savonoski and at the seasonal camp of Ukak. [121]

Along the coast, the Sugpiat/Alutiiq people gravitated to the growing commercial fishing industry. By 1912, the fishing town of Chignik had replaced Katmai as the primary population center on the Alaska Peninsula pacific coast. [122] The Karluk cannery was sending over steam tenders to gather salmon at Kukak Bay by 1890. [123] For a couple of years, Kaflia had been the site of a saltery and store that was maintained by a man by the name of Foster from Kodiak. [124] Villagers from Katmai and Douglas camped at Kaflia during the summer and fished for their own salmon use, as well as to earn cash working for the saltery. [125] Harry Kaiakokonok, a former resident, remembered the fishing at Kaflia,

That's the fellow [referring to Foster] they work for summertime, salt salmon, the bellies; smoke the backs. All men. Men cutting and salting. Men fishing. The fish in that Kaflia bay, inside, that inner harbor. And they make the hauls, they pull them up to the beach. [126]

In June 1912, there were at least five Natives employed at the Kaflia fishery. Evidently, Harry Kaiakokonok and his family had recently moved to Kaflia and were living in barabaras at the time. [127]

Novarupta Erupts and Forces Katmai Residents

to Leave

In early June 1912, Douglas and most Katmai villagers were already gathered at Kaflia for the summer fishing season. Strong earthquakes that began a few days prior to the eruption sent the remaining six Katmai residents fleeing down the coast towards Cape Kubugakli. The earthquakes also caused individuals from Katmai to Cape Douglas to abandon their camps and gather at Kaflia. [128] On June 6, the Novarupta Volcano, [129] located about twenty miles northwest of Katmai, erupted with such force that it is considered one of the largest volcanic explosions ever recorded. Harry Kaiakokonok, a child at the time, remembers parents calling their kids home and that for three days the sky stayed dark and the people hid inside their houses,

It get hot in those barabaras. We pull off all our clothes. We soak them in water and put them over our face. Those peoples who have mosses in their barabara pour water over those mosses and put them over their nose and mouth so they can breathe. After while we open door and try to see out. All black, everywhere. A little bird fly into barabara. He can't see where he go. We children wash his eyes with water and he stay in barabara with us. [130]

The volcanic burst sent ash into the upper atmosphere where it spread out in all directions. The prevailing eastward blowing winds spread the ash over the eastern portion of the Alaska Peninsula, and across the Strait to cover Afognak Island, the northern half of Kodiak Island, and parts of the Kenai Peninsula. [131] Three kayakers paddled from Kaflia Bay to Afognak for help. In response, the United States Revenue Cutter Service's Lieutenant W.K. Thompson piloted the borrowed cannery tug, the Redondo, and sailed to Kaflia Bay to rescue the people. They found Kaflia village buried in volcanic ash to a depth of three feet. [132]

Harry Kaiakokonok remembered the rescue,

After long time, about three days, it start to get light. Everybody go outside. That stuff all over, like deep snow. Couldn't even see the bay. Bay was like land. Hard to breathe. Then we see that boat coming up the bay. Gee! Was funny feeling. Boat was like coming across dry land. All those stuff was floating on bay, about six feet deep. Dead whales and sea lions and salmons were all mixed up in those stuff floating on top of the bay. [133]

The people, maybe about 100, were taken to Afognak. The U.S. Revenue Cutter Service had heard reports that Katmai residents had left the area prior to the eruption. On June 15th, Service personnel sailed the Redondo to Cape Kubugakli, stopping at Katmai, but did not find anybody in the village or in the area. They sailed on, looking for a family that typically lived at Dakavak Bay during the summers. The house was seen, but not the people, who it is believed had not yet arrived for the season. [134]

|

| Katmai barabaras covered with volcanic ash, 1915. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 1, 3946. |

|

| Fish racks and caches at Old Savonoski in 1918. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 4, 3676. |

A short time later, the Katmai coastal population left Afognak and eventually established the new community of Perryville, located about 165 miles southwest of Katmai along the Alaska Peninsula coast. Ninety-two of the Katmai refugees took part in establishing their new village. The importance of the Russian Orthodox Church in the people's lives is highlighted by fact that "The local chief reported that the people were dissatisfied because they had no church and no bell." [135]

Most Savonoski residents were in the Naknek area at the time of the eruption except for two families who saw the volcanic explosion and fled shortly after the eruption. "American Pete," Chief of Savonoski, was near Ukak at the time, as he was in the process of gathering equipment from his barabara there, when the first explosion occurred. He was quoted as saying,

The Katmai Mountain blew up with lots of fire, and fire came down trail from Katmai with lots of smoke. We go fast Savonoski. Everybody get in bidarka [skin boat]. Helluva job. We come Naknek one day, dark, no could see. Hot ash fall. Work like hell. [136]

Reportedly, the two families tried to return to live at Savonoski, at the head of Iliuk Arm, almost immediately after the eruption. The dust and residual heat, however, made for impossible living conditions. [137] "American Pete" remembered his village fondly in a 1918 interview,

Too Bad. Never can go back to Savonoski to libe again. Everything ash. Good place too, you bet. Fine trees, lots moose, bear and deer. Lots of fish in front of barabara. No many mosquitoes. Fine church, fine house. [138]

The former Savonoski villagers soon established another village, called New Savonoski, located along the south bank of the Naknek River and about five miles east of Naknek. In 1918, 54 people were living there when the flu epidemic hit. In 1953, 19 permanent residents were living there. By 1961 there were three persons living at the village, and at some later date it was abandoned. [139]

The cataclysmic eruption of Novarupta and subsequent ash fallout, flooding, heat and dust, made it impossible for the Katmai people to return to their homes. The landscape significantly changed as ash and pumice choked rivers and streams and thereby altered channels, bays, and water tables. As a result, the historic properties may have been scoured, buried, saturated by rising water tables, and eroded by tidal action. [140]

|

| New Savonoski settlement in 1918. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 4, 4195. |

Historic Properties Summary and Recommendations

Along the Katmai Coast (from south to north):

Katmai Village (AHRS Site No. XMK-014). There have been two documented site visits to the Katmai village area.

In 1915 the National Geographic Society expedition, led by Robert F. Griggs, visited the Katmai area, taking photographs of barabaras, the ROC chapel, graveyard with a wrought-iron fence, and at least two log or wood frame buildings, one of which might have been the trading store. Griggs also discovered signs of a flood that had swept through Katmai village and noted its affect on the buildings and structures. "The Orthodox chapel, through reasonably intact, had been swept off its foundations and bore a high water mark of 5-1/2 feet above the ground. Many barabaras were completely filled with water-borne ash, and the heavy roof of one had been floated away...." [141]

In 1953, archeologists from the University of Oregon visited the site. Wilbur A. Davis and his co-workers found excavating nearly impossible since ash and pumice covered the former village to a depth of 2-1/2 to 5 feet. In addition, the "debris-choked beds of nearby streams had raised the water table so that the former settlement was a series of grass-covered hummocks separated by pumice flats" under which the water rose to within a few inches of the surface. The crew did identify a graveyard with some crosses still standing as well as the chapel remains and the trading post, although the ash and pumice covered the building up to its eaves. [142] It is recommended that the site be visited to see if the ground is now stable enough to permit an archeological investigation.

|

| Interior of the Katmai chapel after the flood, 1915. Photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 1, 3773. |

Dakavak Bay (AHRS Site No. XMK-049). This site "Archaeological Site 49 MK10" was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its prehistoric significance. Archeological investigations also noted one post-contact dwelling at Dakavak Bay. In 1912, a family was known to have seasonally lived in a dwelling at Dakavak Bay. [143] Recommend further historical archeological investigation at the site.

Takli Island, Amalik Bay, and Cape Atushagvik vicinity: This region was probably used at least intermittently, throughout the Russian and American periods. In 1895, the Kodiak priest had left Katmai and was travelling north when he mentioned stopping at a barabara on the way to the narrowest point of land for taking off to Kodiak Island. Undoubtedly other structures are located in the area. Recommend further historical archeological investigation.

Kaflia (AHRS Site No. XMK-007) is located close to Kaflia Bay. Wendell Oswalt's 1954 archeological investigation at Kaflia revealed the remains of four historic semi-subterranean houses, including some with tunnel entrances. The suggested occupation dates are circa AD 1500-AD 1912. This site could be related to the seasonal fishing camp and fishery, that included a saltery and store, which was active prior to the 1912 eruption. There has been some vandalism at the site. Recommend further historical archeological investigation.

Kukak Village (AHRS Site No. XMK-006), located on the north shore of the bay, is listed on the National Register for its prehistoric significance. Archeological investigation that did not focus on the historic material, discovered some historic remains and artifacts including a collapsed structure made of boards, bricks, bottle glass and a gun barrel. No archaeological investigation has been done since the 1960s. Roy Fure, a trapper in the Katmai area during the early 1900s, stated that prior to the eruption, only trappers were living in the Kukak area. Recommend historical archeological investigation. Site is on ROC land.

At nearby Old Kukak (AHRS Site No. XMK-015), archeological site visits noted several mounds that could be the remains of dirt-floored cabins that were standing at the time of the 1912 eruption.

Northwest of Kukak (AHRS Site No. XMK-046). Archaeological testing in 1964 identified six house size depressions and determined that the site was occupied during post-contact times and probably for a short duration. Recommend historical archeological investigation for all three Kukak sites.

Hallo Bay. Roy Fure saw about nine houses in this area in 1914. This was the terminus of a route across the peninsula to Savonoski and Naknek. Recommend historical archeological investigation. [144]

Douglas (Kaguyak) (AHRS Site No. AFG-043). Listed on the National Register of Historic Places for both prehistoric and historic significance. Archeological investigations identified the remains of several historic properties including the Russian Orthodox Church chapel, a cemetery, thirteen historic houses, tent frames, outbuildings, a kazhim, and possible cabin foundations. A 1964 site visit noted that the church had been vandalized and burned. Recommend working with the ROC owner to reinvestigation the area with an historical archeological focus. Some vandalism has already occurred at the site. Recently, the ROC has been leasing this land to a tourism operator. The ROC should be encouraged to work with NPS and other appropriate groups, namely the Katmai descendents, to protect this site that includes a cemetery.

Swikshak (AHRS Site No. AFG-044), near Swikshak Lagoon. A 1989 site visit by archeologist noted a historic midden. Recommend further historical archeological investigation.

Cape Douglas: There is potential for finding historic sites related to sea mammal hunting camps located along Kamishak Bay to the south of Cape Douglas. There may also be a trading post located around the Cape Douglas headland. Recent archeological investigations around the Cape Douglas headland documented the following sites:

(AHRS Site No. AFG-202) on the southwest side of the cape. The 1994 NPS SAIP [145] archeological investigation noted an historic settlement consisting of three house depressions. One house is rectangular (4 m x 3m) with horizontal milled floorboards and vertical posts.

(AHRS Site No. AFG-108) on the north shore of Cape Douglas. A 1989 archeological investigation noted two rectangular, historic cabins outlined with sod berm. Foundations are 3m x 4m with clear entryways.

(AHRS Site No. AFG-107) on the east end of Cape Douglas. 1989 archeological investigation noted a possible structural depression.

(AHRS Site No. AFG-171) on the southeast end of the cape. A 1990 archaeological investigation documented two houses. One house has a large chamber with multiple siderooms that indicate similarities with late prehistoric and early historic periods on Kodiak Island. The second house is considered to be post-contact with its associated vertical posts that were cut with a metal saw. It is also considered to have been a ruin prior to the 1912 eruption. Located nearby were historic debris that includes stove parts, a pickaxe head, iron spikes, cut nails and iron fragments. All iron is heavily rusted. The site may be associated with a Sugpiat/Alutiiq occupation and perhaps sea mammal hunters.

Ashivak (AHRS Site No. AFG-037). This is not the location identified on modern maps, but is closer to Cape Douglas along the coast. This is considered an historic site with chipped knife blade and scraper. Recommend further historical archeological investigation.

Naknek River Drainage:

|

| The waterfront at Old Savonoski showing the main line of barabaras. 1918 photo courtesy of University of Alaska Anchorage, Archives and Manuscripts Department, National Geographic Society Katmai Expedition Collection, Box 4, 3675. |

Savonoski (AHRS Site No. XMK-001). This former settlement is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its prehistoric and historic significance. Photographs from the National Geographic Society's expedition of 1916 showed several barabaras lined up along the river with elevated wooden caches behind the houses, one house made out of peat moss blocks, and the log Russian Orthodox chapel. A 1953 archeological investigation of Savonoski revealed many historic properties including fifteen semi-subterranean houses, filled in by sand and pumice, with split cottonwood log frames and rectangular shapes. The high water table level prevented excavation of the kazhim. Little remains of the site today.

Savonoski River Archaeological District (AHRS Site No. XMK-053) includes two sites. This district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for prehistoric and historic significance. Evidence of the historic period was found during the 1964 archeological investigation at Kanigmiut (AHRS Site No. XMK-003) which revealed about nine house depressions.

Grosvenor Site (AHRS Site No. XMK-004). Roy Fure reportedly visited this site in 1914 and saw three barabaras on the stretch of land between Grosvenor and Coville lakes. Archeological investigations in 1963 noted several surface depressions in the area.

Brooks River Archaeological District (AHRS Site No. XMK-051). This is a National Historic Landmark site that includes caribou hunting and fishing camps with more or less continuous occupation until about AD 1820. The site include an AD 1900 historic house depression (AHRS Site No. XMK-037).

Alagnak River Drainage:

Alagnak River Russian Orthodox Chapel (AHRS Site No. DIL-036). A 1997 archeological investigation identified and documented the remains of a log ROC chapel. The chapel consisted of a vestibule and nave with a bay. There is a stack of three ROC grave markers at the site. Recommend ethnographic study, and research of Alaska Russian Orthodox Church records as related to the Nushagak Mission to reveal the history and use of this chapel.

Endnotes

1 Black, "The Russian Conquest of Kodiak," Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 24, numbers 1-2, 177.

2 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 114

3 Davydov, Two Voyages to Russian America, 191. Davydov provided this description of the hunting posts; "At various places along the coast of the island [Kodiak] there are small posts in which groups of hunters live—this is called an artel, and is supervised by a baidarshchik. The baidarshchiks receive their orders from the manager and pass them on to the [natives]. In addition to artels, in some places there will be one promyshlennik [Russian hunter] living with several Americans...., and such an organization is called an odinochka [one-man post]."

4 Hussey, Embattled Katmai,114; Tikhmenev, A History of the Russian American Company, Vol. 2 1979, 7.

5 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 115 (citing Bancroft, History of Alaska, 321). Morseth, People of the Volcanoes, 34, cited a 1787 report that the baidarshchik and his men stationed at the artel near the Native Katmai settlement had been killed.

6 Davydov, Two Voyages to Russian America, 1802-1807, 191.

7 Tikhmenev, History of the Russian American Company, Vol. 2, 9-10.

8 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 250; The 1880 U.S. census stated Katmai's importance: "Under Russian rule, Katmai controlled the trade of the upper Naknek area and into Bristol Bay, Nushagak and "Kolmakoosky" areas (Ivan Petroff, U.S. Census Office, Tenth Census).

9 Davydov, Two Voyages to Russian America, 1802-1807, 192.

10 As noted by Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 157. In 1791, Shelikhov's men from the Kenai post retaliated to the Alaska Peninsula inhabitants for participating in the destruction of the Katmai crew. The Katmai post was established in 1794 according to VanStone, Russian Exploration in Southwest Alaska: the Travel Journals of Petr Korsakovskiy (1818) and Ivan Ya. Vasil'ev (1829) (Fairbanks, The University of Alaska Press, 1988), 67.

11 Tikhmenev, A History of the Russian American Company, Vol. 2 (1979), 64.

12 Russian Orthodox American Messenger (ROAM), 1(4):57-58, 1896, "From the Travel Journal for 1895 of a Priest of the Kodiak Resurrection Church-Tikhon Shalamov," translated by Richard Bland, May 1999. All ROAM articles used in this study were translated by Richard Bland, May 1999. According to Katherine Arndt (personal communication, 30 July 1999), the Alaska Russian Orthodox Church records state that Katmai was located between mountains.

13 Khlebnikov, Notes on Russian America, 40.

14 Fedorova, The Russian Population in Alaska and California: Late 18th Century-1867, (Kingston, The Limestone Press, 1973), 200; 1821 inventory.

15 Khlebnikov, Notes on Russian America, 40.

16 Tikhmenev, A History of the Russian American Company, Vol, 2, 14.

17 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 96.

18 Unrau, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Alaska, Historic Resource Study, 40.

20 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 105.

21 Langsdorff, Remarks and Observations on a Voyage Around the World from 1803 to 1807, 30 and 140.

23 Gideon, The Round the World Voyage of Hieromonk Gideon 1803-1809, 141. The Alaska Russian Orthodox Church Records will undoubtedly provide more information about the Savonoski settlements during the Russian and early American time periods.

24 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 168.

25 Dumond and VanStone, "Paugvik," 7.

26 Katherine Arndt, University of Alaska Fairbanks, a noted scholar of the Russian-America period who is currently preparing a Katmai ethnography; personal communication, 8 June 1999. Although this figure is listed in Fedorova, The Russian Population in Alaska and California: Late 18th Century-1867, (Kingston, The Limestone Press, 1973), 200, Arndt clarifies that this was a mistranslation and should be read as the collective population figure for the villages within the jurisdiction of Katmai. As these six settlements were listed for the Katmai jurisdiction in 1830 or 1831, it is likely that these same settlements existed in 1818.

27 Katherine Arndt, citing Alaska Russian Orthodox Church Records, personal communication 7 June 1999. It is also possible that Naushkak, was the same settlement located on modern maps as "Kaguyak," since Orth's Dictionary of Alaska Place Names, 484, includes "Naouchkak" as a name variant for Kaguyak.

28 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 108-109. Hussey states that it is not clear how Vasiliev acquired this interior name, and that it is also possible that another "Vasiliev," who traveled with Etolin and Khromchenko in 1921-1822, may be responsible for reporting the name "Naugeik."

29 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 106-107.

32 One such example of a Suqpiat/Alutiiq hunting party was noted by Khlebnikov: A sea otter party formed by the Katmaiskaia odinochka, consisting of 15 baidarkas of Aliaskans and two baidarkas from Sutkhumskaia odinochka and hunting on the east shore of the Aliska Peninsula from Kamyshak Bay to Sutkhum odinochka, obtained eight sea otters, five young sea otters and two pups. Office Manager V. Kashevarov. (Khlebnikov, Notes, 362.)

33 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 143-146. The 1820 register for native men at Fort Ross included the Village of Katmaiskoe, Fedorova, Ethnic Processes, 12. Marina Ramsay's translation of Richard Pierce's Documents on the History of the Russian-American Company, 121-122, provide specific references about Katmai toions in Sitka in the 1800 instructions to Baranov by V.G. Medvednikov (who was in charge of Novo-Arkhangel'sk). Medvednikov encouraged the rewarding of native hunters, including "the Katmai toion Gavril" and that when the main party arrived from Kodiak, to order the hunters, "the Katmai toion Efim, Nunalkudak and Kumyk to disclose and show the best hunting spots to the south which they know."

34 Tikhmenev, A History of the Russian American Company, Vol. 2, 1979, 77.

35 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 163-164.

36 Unrau, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, 45.

37 Khlebnikov, Notes on Russian America, 349-50.

38 Source of census figures for 1792, 1800, 1821 and 1825 are Khlebnikov, Notes on Russian America Parts II-V, 7-8; source for 1818 Arndt, personal communication 8 June 1999. Source for Katmai 1862 is Arndt, citing Church records based on Katmai visit by priest that year. Of note, a population figure given for Katmai (which may be for the Katmai jurisdiction) for 1860 or 1863 was 457 as noted in Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 157 (citing Tikhmenev II). Source for 1850 is Dumond, Demographic Effects of European Expansion, 16. Source for 1861 is Arndt, citing Church records based on the visit by a priest of that year, personal communication, 30 July 1999.

39 In 1844 there were two Savonoski settlements listed in the ROC records called Ikak and Alinak. Two settlements continued at least through 1865 and were listed in the Church records as 1st and 2nd Severnovskoe settlements ("Info on the Severnovski Settlements from Alaskan Russian Church Archives," compiled by K. L. Arndt, May 1999, Katmai HRS).

40 Katherine Arndt, personal communication 30 July 1999, citing her translation from the Records of the Russian American Company Correspondence of the Governors General Communications Sent, vol. 15, No. 180, folios 251-251, Kupreianov to Main Office, 1 May 1838.

41 Fortuine, Chills and Fever, 203, 233.

42 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 128, 180.

43 Arndt, personal communication, 7 June 1999.

44 Arndt, personal communication, 8 June 1999.

45 Dmytryshyn, The Russian American Colonies, Vol. 3, 444. Circa 1840-1845.

46 Arndt, personal communication, 8 June 1999; Dumond and VanStone, "Paugvik," 8.

47 Dumond and VanStone, "Paugvik," 8.

48 Although it is not clear how many settlements were located in this area and for what length of time periods, there does appear to be some continuity of a settlement being located at the head of Naknek Lake (eastern end), at the end of Iluik Arm, throughout the early American period. According to the Alaska Russian Orthodox church records, this settlement was known primarily as "Iqkhagmiut" from the mid 1870s through the early 1900s, for a couple of years its was "Severnovskoe," and from 1910-1912 it was listed as "Nunamiut." What follows is a further discussion on these settlements and names gathered from Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 248-249, 252 and 257, and Katherine Arndt's "Info on the Severnovski Settlements from the Alaskan Russian Church Archives," May 1999, Katmai HRS. Hussey noted that early American maps showed that the settlement located at the head of Naknek Lake was best known as "Ukak." In 1872, Alphonse Pinart's map showed two settlements: one at the head of Iliuk Arm as "Haknik" and the other located to the north and at the end of the Katmai trail as "Ikak." In 1880, Petroff reported "Ikkhagmute" as the name used by its inhabitants for the settlement at the end of Iliuk Arm. Hussey noted that from 1890 forward the name "Savonoski" or it variants appeared more consistently. Arndt's research of the Alaska Russian Church archives about these settlements revealed the listing of one settlement called "Iqkhagmiut from 1876-1897, which was listed as "Severnovskoe" from 1895-1897. J.E. Spurr's report of his 1898 trip through the area noted that name for the village located at the head of Naknek Lake "is Ikkhagamut, or Savonoski, as it is now commonly called." Spurr also noted that a former Native settlement called "Naouchlagamut" was located about 15 miles east of Naknek Lake near the Savonoski River (place name variation is "Nauklak" according to Orth, Dictionary of Alaska Place Names, 677). Arndt's research found reference to the existence of two settlements in 1898 by the priest Vladimir Modestov who referred to the Severnovkoe settlement and the upper Severnovskoe settlement or out-settlement located 10 miles from the former. The Church records also showed a listing for the upper settlement called Kanigmiut from 1902-1912 and that the other Severnovskoe settlement was referred to as "Nunagmiut in 1896, "Iqkhagmiut" through 1909, and Nunamiut from 1910-1912.