|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 10:

RECREATION AND TOURISM

Early Recreational Trends

Before the Klondike gold rush began, there was little pressure on Alaska or Yukon game resources except in the vicinity of widely dispersed mining camps and cannery sites. The gold rush, however, lured tens of thousands of people northward. By 1900, Alaska had more than twice the population than it had had in 1890; its non-Native population, moreover, grew more than 750 percent during the same ten-year period. [1]

The Lure of the Kenai Peninsula Gamelands

|

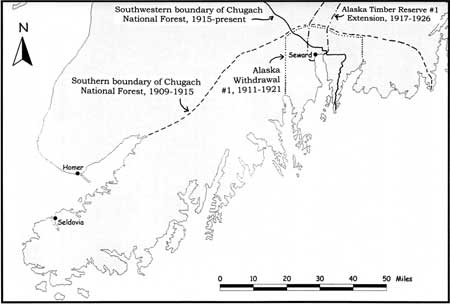

| Map 10-1. Historic Sites-Recreation/Tourism. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As a direct result of the gold boom, market hunters and individual prospectors fanned out across Alaska in search of game. The publicity that accompanied the gold rush also attracted trophy hunters, few of whom had visited Alaska previously. On the Kenai Peninsula, the Hope-Sunrise area had supported a growing population since 1894, and hunters were active along the Kenai coast during the mid- and late 1890s. As a result, the wildlife inevitably began to suffer. Dall De Weese, a hunter and travel writer, was able to count 500 sheep within six to eight miles of a spot in the Kenai Mountains in 1897; four years later, however, the number of animals had drastically declined. Similarly, hunter Andrew J. Stone noted in 1900 that "the Kenai Peninsula ... has been prolific in animal life but there are so many sportsmen now coming in that the large game is suffering quite a slaughter." (One author felt that non-resident sportsmen were a major culprit; although the game laws "allowed them to kill only two moose, three sheep, three bear, etc., [they] would kill all the animals they could lay their eyes on.") [2] Caribou were particularly vulnerable. Market hunters during the early 1900s exterminated the species in the Kachemak Bay area; in the years that followed, hunters were so successful in their endeavors that the last caribou were eliminated from the Kenai Peninsula about 1913. [3]

By 1905, both the Klondike gold rush and the Hope-Sunrise excitement had passed their peak, and as a result, pressure on the Kenai Peninsula game populations began to diminish. The Kenai, moreover, gained increasing fame as a sport-hunting destination during the years following the gold rush; by 1911, one source noted that it had "come to be regarded as the greatest game country in the possession of the United States." [4] Its popularity stemmed from its accessibility, the variety of local megafauna (specifically moose, sheep, bear, and goat), and the existence of many trophy-size animals. [5]

The gamelands, located in the hills and flatlands of western Kenai Peninsula, were reached via Kenai during the gold rush period. By 1905, however, construction of the Alaska Central Railroad had proceeded to the point that Seward became the primary entrepôt to the gamelands. Thereafter, most hunters who planned a Kenai Peninsula hunt sailed to Seward where they met a guide. They then took the train north to Kenai Lake, after which they sailed the length of the lake and floated down the Kenai River to the gamelands. As noted in a contemporary article, hunters looking for moose headed most often to Skilak Lake, Kenai Lake, Kenai River, [Lower] Russian Lake, the Chickaloon Flats, or "Kusiloff Lake." Sheep hunting areas included Sheep Mountain, False Creek, Stetson Creek, Skilak Lake, and Tustumena Lake. Goat hunters headed to the eastern peninsula, near Spencer and Bartlett glaciers, and both black and brown bears were scattered about the moose and sheep hunting country. [6]

By 1910, hunters throughout the world had heard about the Kenai Peninsula gamelands, and each year thereafter a smattering of hunters arrived in Seward. Some came for the spring bear hunt, while others arrived to take advantage of the fall moose and sheep hunt. The sportsmen hailed from all over the United States and from foreign countries as well, particularly from Europe. [7] The number who arrived each year was fairly small–usually just 10 or 15 parties totaling 25 or 30 hunters–but their wealth, their influence, and their penchant for publicizing their adventures via books and articles played a large role in broadcasting the Kenai's game resources. [8]

The Kenai Peninsula gamelands were essentially unregulated until May 1908, when Congress passed (and President Roosevelt signed) a law providing for major revisions to the Alaska Game Law of June 7, 1902. The 1908 law mandated that all Alaska hunting guides be licensed; in addition, the law recognized both the popularity and the fragility of the Kenai gamelands when it demanded that all Kenai Peninsula sport hunters be accompanied by a licensed guide. No other Alaska hunting grounds were singled out with this requirement. The law helped ensure the continuity of the Kenai game resource.

One beneficial effect of the 1908 law was that it brought forth a small corps of locally based guides, who gained fame (and some fortune) through their guiding efforts. By 1911, ten of Alaska's fifteen guides listed a Seward address. (The other five lived in Kenai.) Well-known guides living in or near Seward included Andrew Simons, Charles Emsweiler, Ben Sweazey, Bill De Witt, and Andrew Berg. Most if not all of these guides earned the respect of men who had hunted trophy animals throughout the world. [9] Another guide, who joined the ranks during the 1920s, was Luke Elwell. The Seward-bred guide lived in town for more than a decade; then, in 1939, he and his wife Mamie built a lodge at Upper Russian Lake and operated it for the next twenty years. The lodge was (and is) the first permanent habitation north of the present-day park boundary; it is also the largest structure between the park boundary and the Kenai River. [10]

One site along the hunters' route became a point of interest for tourists. Roosevelt, a station stop on the east side of Kenai Lake, had long been a transfer point and roadhouse for hunters heading west to the game country. Then, in August 1923, Nellie Neal announced that she had purchased the roadhouse. Neal, a former market hunter and cook in the railroad construction camps, soon married a Seattle electrician named William B. Lawing. The new Ms. Lawing, hoping to cash in on the expected boom in tourist travel on the recently completed railroad, cleaned out a building that was located in the narrow strip between the lake and the railroad right-of-way. Then, according to a local news report, she "placed her entire exhibit of fine Alaskan skins and furs on exhibit." The stop, which was renamed Lawing, became increasingly well-known; thousands of Alaska tourists (and residents) stopped there during the 1920s and 1930s. [11]

Seward Area Land Reservations

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, the federal government–specifically, the Interior and Agriculture departments–reserved land along the Kenai Peninsula's southern coastline. These actions may have prevented a broad range of development actions on the lands in question. Most of these withdrawals were the manifestation of events taking place away from southcentral Alaska. The reservations, however, were temporary, and they had a minor if not insignificant impact on Seward-area land use development. They have been presented in this chapter because the Interior Department has reserved several large blocks of Kenai Peninsula land in recent years; each of these actions, including the reservation that eventually resulted in Kenai Fjords National Park, was made to enhance recreational opportunities and preserve non-economic values.

The first agency to reserve a large area along Alaska's southeastern coastline was the Interior Department's Bureau of Forestry. In August 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt had proclaimed the establishment of the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve. The Bureau of Forestry administered this area, which comprised a portion of what is now known as Tongass National Forest. Roosevelt, well known as a conservationist, chose William A. Langille to head the reserve. Langille established a reserve headquarters in Wrangell, although he later moved to Ketchikan.

In 1904 and 1905, Langille made several long trips, at the behest of his Washington superiors, to inspect either recently withdrawn areas or areas proposed for withdrawal. One of those trips, beginning in September 1904, took him to Prince William Sound, where he made an examination the area's forest resources. He continued on to Seward, then headed overland to Kenai. He eventually wound up in Seldovia, where he boarded a coastal steamer and sailed back to Resurrection Bay. [12]

Langille, among his duties, was asked to evaluate the idea of a Kenai Forest Reserve. Those whom he encountered during his sojourn had mixed feelings about the proposal. A few recognized the importance of the forestry movement, and others (particularly along the railroad corridor) were opposed to the proposal, but most were indifferent. Langille himself reflected those sentiments; he noted that "The existing forest reserve law ... is too restricting and in a measure unjust to so new a country...." For that reason, he hoped that land would still be available for settlement in any new reserves. Given that caveat, Langille recommended the creation of a reserve that would encompass most of the northern and central Kenai Peninsula; specifically, he recommended that the reserve include the entire peninsula north of a line that connected Cape Puget (40 miles southeast of Seward) with "Coal Inlet" (Kachemak Bay). [13]

There was no immediate response to Langille's proposal. The Bureau of Forestry, meanwhile, underwent major structural change. In February 1905, the Bureau became part of the Agriculture Department; a month later, the bureau's name changed to the U.S. Forest Service; and in 1907, the agency changed the name of its forest reserves to national forests. [14] Historian Lawrence Rakestraw noted that soon after the establishment of the new agency,

there came a flurry of activity within the Forest Service regarding new reserves.... The Alaska reserves came up for consideration, and by March [1907] the Forest Service had decided to create new reserves, both in southeastern Alaska and in the Prince William Sound area.

President Roosevelt responded to that activity by proclaiming the Chugach National Forest on July 23, 1907. The forest, at this time, comprised just 4,960,000 acres, more than a million acres smaller than today; its western boundary snaked along the peninsula's eastern edge. Kenai Lake, the Quartz and Canyon Creek valleys, and the Hope-Sunrise area–all part of the Chugach today–were omitted from Roosevelt's 1907 proclamation. [15]

Just a few months later, in his 1907 annual report, Langille recommended that additional areas–primarily along Turnagain and Knik arms–be added to the Chugach in order to protect them from Alaska Central Railroad construction crews. That order was sent on to Washington, where it and other proposals lay until the closing days of the Roosevelt administration. On February 23, 1909–less than two weeks before William Howard Taft assumed the presidency–Roosevelt more than doubled the size of the Chugach, to 11,280,640 acres, the largest in the country. The proclamation, which institutionalized the boundaries that Langille had recommended in 1904, spread the previous boundaries of the national forest in several directions. It included all of the Kenai except for the area south of a sinuous line that connected Cape Puget with the head of Kachemak Bay (see Map 10-2). That line, for the most part, followed the drainage divide. Most of the Kenai Peninsula land not included in the Chugach, therefore, drained south into the Gulf of Alaska. The newly expanded forest included several thousand acres that are within the present park boundaries; almost all of that land is on the high-elevation portions of Harding Icefield. [16]

|

| Map 10-2. Seward Area Land Reservations, 1909-1926. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Sewardites did not hear about Roosevelt's action until several weeks into the new president's term. Local newspaper editor Leo F. Shaw was skeptical about the need for such an action. Shaw noted that "there is apparently little excuse for making a large forest reserve in this part of the territory of Alaska. There are practically no valuable forests in the section of the country included in the reserve." [17]

It is of more than parenthetical importance to note that Kenai's south coast was thrice considered for inclusion in Chugach National Forest. Forest Service historian Lawrence Rakestraw notes that the February 1909 addition had originally been planned to include the south Kenai coast, but commercial interests in Seward objected, so the crest of the range to Kachemak Bay was used. Two years later, in a report on the Chugach, Tongass National Forest head William Langille suggested that "the southern shore of the Kenai Peninsula from near Seward to the head of Kachemak Bay" be added to the forest. Then, in 1913, forester George Cecil visited the area and reported that the timber resources south of Kachemak Bay were superior to those north of the bay. Neither Langille's nor Cecil's observations, however, resulted in boundary modifications. [18]

On December 5, 1911, the federal government declared a land freeze in the Seward area. In anticipation of "future legislation" (which was probably the Congressional act of August 24, 1912, which authorized a commission to study various rail routes to the interior), the General Land Office established Alaska Withdrawal #1. The newly-designated land, which was "withdrawn from settlement, location, sale, or entry," stretched along the coast from Day Harbor to Aialik Bay; it included all land south of the recently expanded Chugach National Forest boundary, and several thousand acres in the present park. That executive order was modified in August 1912 to allow the "use or disposition of timber" within the recently withdrawn land. This latter provision was probably implemented to make the area's wood resource available to government rail construction crews. [19]

The General Land Office continued to be concerned about timber resources. In the summer of 1915, it created the huge Alaska Timber Reserve #1 in the Susitna and Nenana river drainages to ensure an adequate timber supply for the railroad construction crews. In April 1917, that reservation was extended to include a tract five miles on each side of the government railroad from Seward to the Knik River. The latter action included within its scope a few thousand acres currently included within Kenai Fjords National Park. [20]

Even before the three reservations had been created, action to nullify them had begun. In 1913, Alaska Delegate James Wickersham submitted a U.S. House bill to abolish the Chugach National Forest because of its relative lack of timber; a short time later, the newly created Alaska legislature passed a resolution in support of Wickersham's action. The General Land Office, perhaps in response, decided to tailor its boundaries to more closely circumscribe timbered lands. The agency recognized that "the public good will be promoted by adding to the Chugach National Forest ... certain lands, and by excluding certain areas therefrom and restoring the public lands therein." It prepared a proclamation to that effect, and on August 2, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson signed the proclamation that, on the Kenai Peninsula, modified the Chugach's boundaries to resemble their present configuration. (This action added to the forest the large tract of land on the northeast side of the Resurrection River, but eliminated the huge area in the western Kenai north of the coastal drainage divide.) [21] The following year, forester Asher Ireland visited the Seward area and recommended that 8,641 acres on the southwest side of Resurrection River be added to the forest. Ireland considered the parcel, which contained 42 million feet of spruce and hemlock, valuable both for both timber and protective cover; it had, in Ireland's opinion, "the best body of timber in southwestern Alaska." [22] Ireland's recommendation, however, was not enacted into law.

During the 1920s, the other reservations were eliminated, probably at the urging of local authorities. Seward Senator L. V. Ray sponsored a joint memorial in the 1919 Alaska legislature requesting the "restoration or modification" of Alaska Withdrawal #1. The General Land Office, in response, "appreciated that most of the reasons for the withdrawal have ceased to exist," but it was not until May 1921, with construction of the government railroad nearly completed, that Alaska Withdrawal #1 was "vacated and annulled" by President Warren Harding. Five years later, in November 1926, President Calvin Coolidge issued a similar executive order revoking Alaska Timber Reserve #1 on the Kenai Peninsula. Except for land in the newly reduced Chugach National Forest, most if not all of the Kenai Peninsula was now open, once again, to location and entry. [23]

Although the federal government appears to have paid an extraordinary amount of attention to the Seward area's forestry resources during this period, there have been no known attempts or proposals to secure timber for commercial purposes in or near the present park boundaries. Isolation, inaccessibility, the lack of potential board feet, and the lack of markets all help explain the absence of commercial timber operations. [24]

Visitors to the Southern Kenai Coast,

1900-1940

Early Sightseers and Hunters

Both sightseers and hunters have been attracted to the Seward area since the earliest years of the twentieth century. Tourists, to be sure, were few and far between during the first decade after Seward's founding. Most of the visiting hunters, moreover, were merely passing through on their way to the western gamelands.

Seward's earliest residents were well aware of Resurrection Bay's tremendous scenic attributes, and less than a year after the town's founding, the bay was being used for recreational sailing trips. [25] These trips probably continued, on an intermittent basis, for years afterward.

Relatively few people sailed along the outer coast during the twentieth century's first decade, but some of those that did were well aware of its scenic beauty and tourist potential. Ulysses S. Grant and D. F. Higgins, Jr., two government geologists, sailed the Kenai coast in 1909 and were thunderstruck at what they saw. In a 1913 monograph they wrote, "It is hoped that this publication may attract attention to some of the most magnificent scenery that is now accessible to the tourist and nature lover." [26]

During this period, Alaska tourists were seldom seen outside of the southeastern "Inside Passage" route, and those who sailed "to the westward" were a rare sight indeed. The decision to build a government railroad, and the line's subsequent construction, however, took place at the same time in which tourists were showing an increased interest in Alaska as a destination. As a result, tourism became increasingly evident in Seward and other southcentral ports during the years that immediately preceded World War I. Beginning in 1912, the Alaska Steamship Company advertised trips into the area. The advertisements apparently met with some success, and when the Pacific Steamship Company–the successor to the Pacific Coast Steamship Company–began operations in 1916, it too advertised for tourists. The World War I years were particularly successful for Alaska tourism because European travel was prohibited. Thus, it is highly likely that an increasing number of tourists during this period visited Seward, Kodiak, Seldovia, Anchorage, and other southcentral ports. [27] The route for some of these ships–both from "Alaska Steam" and from "the Admiral Line"–undoubtedly paralleled the outer Kenai coast. The route for the large steamships, however, took passengers on a more southerly route, away from the coast. Clouds and storms, moreover, often obscured the view. For these reasons, the few tourists who may have been aboard these ships saw only an occasional, distant glimpse of the outer Kenai coast. [28]

Hunters were also attracted to the area. As noted above, hunters from around the world passed through Seward each spring and fall on their way to the famed western Kenai gamelands. But others hunted locally. In February 1907, lands within the present park received favorable publicity when an article by local hunter Edwin Lowell was published in Recreation Magazine. The article concerned a moose hunt that he and a fellow Sewardite had taken "around the head of the Resurrection River" the previous September. [29]

Hunting was a popular pastime among Seward residents, and in October 1910 sufficient numbers of them gathered to organize the first of several "big game hunts." In this activity, local hunters were divided into teams; the teams received points according to the species of game that they obtained during the restricted time of the contest. Upon hearing of the contest, eastern big game hunters howled in protest, fearing a wholesale slaughter of game. The protesters were told, however, that the participants all adhered to the game laws and that all meat obtained was either consumed or put into storage for future use. The Seward Outing Club, which may have been an outgrowth of those hunts, was well established by 1914; it was one of a series of organizations that had been formed in the early twentieth century in towns along the southcentral Alaska coast. [30] Available evidence suggests that the vast majority of hunting by Seward residents during this period took place within a few miles of town or near the railroad right-of-way. As has been detailed below, an insignificant amount of sport hunting took place within the present park boundaries.

Rockwell Kent's Visit to Renard Island

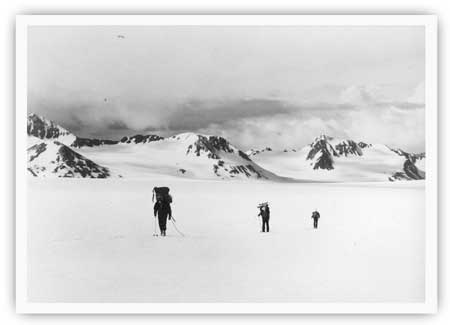

|

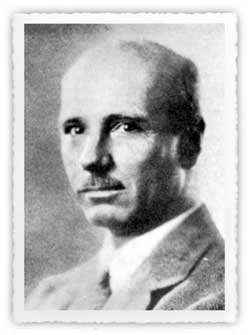

| Rockwell Kent, a budding author and artist, spent the winter of 1918-1919 at a fox and goat farm on Renard Island in Resurrction Bay. Current Biography, 1942, 447. |

In August 1918, a relatively obscure writer and illustrator named Rockwell Kent and his nine-year-old son sailed into Seward and checked in at the Sexton Hotel. The elder Kent, aged 36 at the time, had studied architecture and art; upon leaving school, he became an adventurer. When he arrived in Seward, he was not a tourist. Instead, he came to Alaska, in part, because he was a free-hearted spirit. And because he loved German literature and culture, he also sought a refuge from the jingoistic, anti-German sentiment then rampant in the United States. In addition, he noted,

I came to Alaska because I love the North. I crave snow-topped mountains, dreary wastes and the cruel Northern Sea with its hard horizons at the edge of the world where infinite space begins. Here skies are clearer and deeper and, for the greater mystery of those of softer lands. [31]

More specifically, Kent chose to visit Seward because he "did have a love for the isolation and wonder of island life," and he ideally sought a location "that combined the quiet dignity of the primitive forest with the excitement of the ever-changing ocean." [32]

He found such a location soon after he arrived. While rowing in the bay, he and his son met a 71-year-old fox and goat farmer named Lars Matt Olson. During the course of their conversation, Olson invited the two to visit him on Renard (Fox) Island, and on August 28, the two moved into a cabin near Olson's residence. Kent and his son remained on the island for more than seven months; the elder Kent spent much of that time writing, drawing, and enjoying a simple, primitive existence. The illustrated narrative of his experience, which he called Wilderness; A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, was Kent's first published book–and one of his best. The New York Times called it a "very beautiful and poignant record of one of the most unusual adventures ever chronicled;" it has also been called "a unique book and [an] unrecognized classic in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau's Walden." The woodcuts with which he illustrated the volume were notable as well; the public reportedly "gobbled up his work" when it was exhibited in New York. One biographer has noted that "With the appearance ... of his 64 Alaska drawings, Kent suddenly became one of the top-notch illustrators. His illustrations, in subsequent years, ... have become collectors' items." Critics also praised the book for its deft interplay of text and illustration; according to Frank Getlein, "many critics consider [Wilderness as one of] the best American books ever produced in terms of harmonious balance between text and pictures." [33]

|

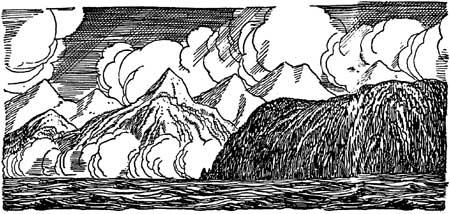

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from his book Wilderness: A Journal of a Quiet Adventure in Alaska, 1920. Courtesy The Rockwell Kent Legacies. |

Kent appears to have savored his life on Renard Island during most of his sojourn, and he wrote extensively about the snow, wind, cold, isolation, and other elements of his immediate surroundings. The book made no attempt to soft-pedal the surrounding climate and topography, elements that were far more similar to the fjord country to the west than of Seward and the surrounding railbelt. (Caines Head, for example, was "a merciless shore without a harbor or tending place;" Bear Glacier was a place from which "the winds blow forever fiercely and ice cold;" and Renard Island itself was "warmer and much wetter [than Seward], and even the wind blows there when Seward's waters are calm.") Kent, during his stay, never ventured within the boundaries of the present park; the closest he came was a yearning to visit Bear Glacier that manifested itself during a visit to nearby Sunny Cove. He did, however, complete paintings of the present park coastline; one features Bear Glacier, while another looks from Renard Island toward Resurrection Bay's western shore. [34]

Kent, artistically and spiritually, appears to have embraced his experience on the island. Shortly after leaving, he exulted, "Know, people of the busier world, that there on that wild island in Resurrection Bay is to be found throughout winter and summer the peace and plenty of a true Northern Paradise...." [35] The popularity and the positive tone of Kent's reminiscence, however, did not result in increased tourism to either Alaska or the Seward area, for two reasons. Kent's book, successful as it was, appealed primarily to a small, literary audience. [36] In addition, almost everyone that visited Alaska during this period demanded the modern-day amenities that steamship travel provided; tourists thus had little interest in emulating Kent's strenuous, primitive experience.

Renard Island, and other points in southern Resurrection Bay, were fairly popular visitor destinations both before and after Rockwell Kent spent his winter there. Several visited the island, either on day trips or on overnight camps, while others sailed "down the bay" without disembarking. Several Sewardites, to be sure, paid social calls on Kent (and Olson) during the winter of 1918-19, but few latter-day tourists were so captivated by Wilderness that they felt the need to visit the island where they had resided. The cabin in which Kent and his son lived eventually collapsed. Today, there are almost no physical remnants of the cabin where the Kents stayed, and a tourist lodge was built in the mid-1990s on the Olson cabin site. [37]

Seward Becomes a Tourist Node

After World War I, the Alaska tourist trade boomed. The number of tourists increased almost every year from 1918 (when the war ended) through the late 1920s. Although there area few statistics that describe the industry during this period, the number of tourists that sailed to Alaska each year probably doubled, and may have tripled, during the decade that followed the cessation of World War I.

One of the most dramatic tourist growth areas was southcentral Alaska. Prior to the war, the only maintained routes in the region were the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, the Copper River and Northwestern (CR&NW) Railroad, the Alaska Northern Railroad (which operated, on an intermittent basis, for only 72 miles), and a broad network of sled roads and winter trails. But by 1919, the trail between Valdez and Fairbanks had been improved into the Richardson Highway; and, as noted in Chapter 5, the U.S. government purchased the Alaska Northern line and extended the railhead hundreds of miles northward. With the exception of a bridge over the Tanana River, the so-called Alaska Railroad was completed all the way to Fairbanks in early 1922. Most tourists, however, did not begin to travel over the line until the summer of 1923. [38]

The completion of the line gave the prospective visitor to southcentral and interior Alaska an increasing variety of tour choices. A few tourists, as before, remained on board the coastal steamers, disembarking only for day trips in the vicinity of ports. Most people, however, chose to head inland. Tourists opting for a short trip inland disembarked in Cordova, took the CR&NW north to Chitina, boarded an auto stage and rode to Willow Creek on the Richardson Highway. They then continued on to Thompson Pass and Valdez, where they resumed their steamship journey. [39]

Those opting for a longer trip in southcentral and interior Alaska chose the Golden Belt Tour. Passengers on this tour rode the CR&NW north from Cordova to Chitina, where an auto stage awaited them for a trip north to Fairbanks. (Others began their inland trip in Valdez and took an auto stage all the way to Fairbanks.) Once in Fairbanks, tourists boarded the recently completed Alaska Railroad and rode south to McKinley Park, Anchorage, and Seward. Some tourists took this tour in reverse order; in either direction, it was a popular tour for almost twenty years. Those who wanted to avoid the travails of the Richardson Highway opted for the All-Rail Tour, an excursion on the Alaska Railroad from Seward to Fairbanks and return. [40]

Those who hoped to see the north country in a more leisurely manner–and could afford to do so–chose the Grand Circle Tour. Tourists taking this tour package disembarked at Skagway, rode the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad to Whitehorse, and sailed down the Yukon River on a WP&YR boat to Dawson. From there, tourists continued down the Yukon on an Alaska-Yukon Navigation Company steamer to Tanana and Fairbanks, and then rode the Alaska Railroad south to Seward. This tour required more than three weeks of inland travel. It could be taken in reverse order as well, although that option was longer (and more expensive) because of the slower pace of upstream travel. [41]

Because it was a leading Alaska port, Seward had been dealing with visitors ever since its founding. Hunters, most of whom hailed from Outside points, had been streaming through town for years; they used local accommodations, and some of them bought their outfits in Seward as well. The spate of tourists that invaded after World War I, however, had different needs and expectations than any previous group; they made local citizens aware, many for the first time, of the area's tourist attractions and facilities.

Seward residents, to be sure, had been enjoying outdoor pastimes for years; available activities included bear and moose hunting, berry picking, water sports, picnicking, vacation cabins, and mountaineering. Tourists, however, were less willing to "rough it" than locals, and most needed guides and a large-scale form of transportation. But because tourism was such a minor industry, the only local tour was a rail excursion north to Kenai Lake, which had been offered on an intermittent basis (to hunters and fishermen as well as tourists) since the days when the Alaska Northern operated the line. [42] By the early 1920s, tourists were also given the option of taking an auto stage north on the as-yet-uncompleted road to Kenai Lake.

In 1922, Seward development interests investigated a new way to stimulate local tourism. Before this time, local residents had ignored the huge, unnamed ice cap located west of the city. But in March 1922, it was announced that the "monster glacier near here" would "be used as an attraction for tourists this summer." In order to stimulate interest, the Seward Gateway asked local residents to name the feature. One suggested that it be named after Warren Harding, the current chief executive. Harding had made no secret of his interest in Alaska; he had publicly expressed his interest in visiting the territory as early as April 1921 and still planned to do so. Gateway editor E. A. Rucker therefore concluded that "some honor could be shown him by naming this great glacier after him." By April 1922, someone in Seward–perhaps Rucker himself–had decided on the name Harding Icefield. [43]

At first, locals were given few hints about how the nearby ice cap would become a tourist attraction. But in late April, acting mayor Harry E. Ellsworth announced that local businessmen would fund the construction of a trail from Seward south to Lowell Point, and from there up Spruce Creek. The trail would continue over the drainage divide to the eastern edge of Harding Icefield. Promoters felt that the so-called Spruce Creek Trail would have economic benefits because at its terminus, "one hour and fifty minutes walking time" from Seward, tourists could "actually stand on a glacier and be carried across the great body of snow and ice in dog teams. [This would be] a novelty they cannot enjoy anywhere else in the summer time," an attraction that would "prove a great drawing card for tourists." [44]

Local resident Eric Nelson began constructing the trail in mid-July, and by August 12 the trail was complete. Several hikers assayed the route that summer, at least as far as the drainage divide. [45] By all accounts, the trip was awe-inspiring. Local resident D. C. Mathison, who ascended the trail in late July, positively gushed about the glacier as viewed from the ridgeline:

But it is to the west, that ever mysterious west, [where] the greatest attraction lies. Near at hand are deep gorges, glacier-torn mountains, heaved and twisted ridges, smooth and placid lakes, whose shores when not covered with snow are literally strewn with vari-colored stones and pebbles.... In the not too great distance is the vast expanse of Harding glacier.... I am perfectly sure that anyone obtaining a view under the ideal conditions which obtained when I was there, whose very soul was not stirred, who fails to bow in humble acknowledgement of the puniness and insignificance of man, is bereft of one of Nature's greatest gifts — appreciation! Its gigantic size, its monstrous shape, its forbidding appearance, whose frigid bosom only the most rugged and uncompromising peaks have dared to defile.

But I am wasting time in attempting to describe. You should have been where I sat, have this great panorama before you, which to be appreciated must be seen. Only a geologist could tell what has caused the topsy-turvy appearance of the whole country. None but an artist could, with the delicate strokes of his brush and the blending of his colors, do justice to its beauty. No one but a poet endowed with the descriptive language of Shakespeare, the weird imagination of Poe, the rollicking language of Burns or the wholesome simplicity of Edgar Guest, could describe its wonders and its beauties. [46]

The trail remained in use for years afterward. By the spring of 1924 a shelter cabin had been built at the trail summit. That summer, local resident Jo Hofman "arranged dog sled rides ... so tourists could enjoy a unique outing on the glacier." There is little evidence, however, that tourists braved the long, steep trail to ride on dog sleds. Most of those who hiked up the Spruce Creek Trail, in fact, were probably local residents; after 1926, tourist materials no longer advertised the trail. [47]

A more popular way to ascend the slopes west of Seward was the Mount Marathon trail. Since 1916, Mount Marathon had been the site of a July 4 race; a few participants each year, all from Seward, had scrambled up the slopes to Race Point before sliding and tumbling back into town. With the growth of tourism, however, locals began to recognize that non-racers would also like to ascend the mountain because it offered the climber a magnificent view of the town, Resurrection Bay, the outer islands, and the nearby mountains and glaciers. In June 1925 a visitor from Seattle, Ben Poindexter, suggested that he and a group of volunteers blaze such a trail. A trail up the face of the mountain was roughed out that year; it proved popular, both with visitors and local residents. [48]

During the 1920s, many Seward-area tourist attractions were developed in addition to the two trails noted above. In November 1923, for example, the road from Seward to Kenai Lake was completed, and in the years that followed, many Seward visitors took the half-day excursion out to Kenai Lake. [49] In downtown Seward, civic authorities established a waterfront park; complete with fountains and a Russian cannon, its purpose was to ensure that "visitors would find a pleasant scene when arriving by ship or train." Seward residents were proud of the new tourist amenities. Historian Mary Barry notes that on some sunny summer days during the 1920s, "Seward was practically deserted ... as beautiful weather lured the residents to the forests–some to hike the Spruce Creek trail, others to climb Mount Marathon, and the rest to motor to Kenai Lake." [50]

In the summer of 1923, Seward was briefly in the world spotlight when President Harding visited the port as part of his Alaska tour. On July 13, Harding arrived in Seward on the Navy cruiser Henderson; he mingled briefly with the townspeople, then headed inland on a waiting train. At Nenana, he paused long enough to tap in the "golden spike" commemorating the Alaska Railroad's completion (a feat that had been accomplished several months before), then continued on to Fairbanks. By July 17 he was back in Seward; two days later, the presidential party steamed down the bay and headed toward Valdez. [51]

|

| In July 1923, President Harding and his wife visited Seward. Harding is shown in a light-colored coat at the top of the gangway; his wife is in front of him. Neville Public Museum, photo 5658.4 |

Beyond the publicity it shed on Alaska in general and Seward in particular, the trip was notable to the project area in several respects. Harding was particularly impressed with both Seward and Resurrection Bay. He called Seward "a rare gem in a perfect setting." As to the bay, Governor Scott Bone advised Harding that Alaskans wanted to bestow his name on some physical feature. Bone suggested naming a glacier or mountain after him, but Harding, after entering Resurrection Bay, told him that "of all the beautiful scenery and interesting objects we have passed, I would rather have this entrance perpetuate my name than anything else I could imagine." Within an hour, Bone issued a proclamation naming it the Harding Gateway. [52] In addition, the Seward Gateway named the huge icefield west of town in his honor (an action that, as noted above, had first been accomplished several months earlier). Harding himself probably saw no more of the icefield than a glimpse of Bear Glacier, but the Henderson crew saw the icefield in greater detail. The crew spent several days in port while the President's party toured the Alaska interior; on one of those days, local resident Mel Horner guided the crew, a few townspeople, and several tourists south on the newly-constructed Spruce Creek trail. Judging by contemporary press reports, the party hiked to the watershed divide and continued all the way to Harding Icefield before returning to town. [53]

The Alaska Railroad, in conjunction with the various tour packages, developed several Seward-based tourist excursions during this period. In 1926, it revived its Kenai Lake rail tour, using as its northern destination a visit with Nellie Neal Lawing at the Lawing wildlife museum. That same year, rail tourists were given the opportunity to take a day trip to Spencer Glacier, 52 miles north of Seward; the glacier here was within easy walking distance of the train. And in 1927, tourists on a two-day Seward layover were given an opportunity to visit Anchorage. The popularity of these excursions was mixed. The Lawing excursion lasted until 1931, and the Spencer Glacier trip remained until 1935. These two side trips, and the Anchorage excursion as well, had the practical effect of diminishing prospects for Seward-area tourism development. [54]

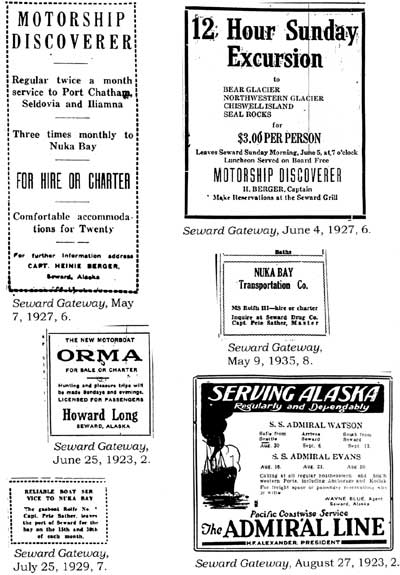

Relatively few Alaska tourists prior to World War II traveled independently (that is, apart from an advertised tour package). For that reason, relatively few out-of-state tourists had more than a few hours' free time while in Seward. Despite that limitation, it appears that some tourists, as well as some Seward-area residents, enjoyed taking boat trips on Resurrection Bay. In 1923, for example, local resident Howard Long advertised his motor boat as being available "for hunting or pleasure trips." The following spring, an article advertised boat trips on the bay for tourists, and a self-styled vacation guide issued in August 1926 urged Seward visitors to "take a motor boat ride to Fox Island." [55] In all probability, small numbers of visitors, primarily from Seward, continued to take Resurrection Bay boat rides each summer from the mid-1920s through the late 1930s.

|

| Advertisements such as these lured early adventurers to the fjord country. |

Tourists and Hunters Visit the Coastal Fjords

As noted above, visitors have been passing through Seward ever since the town's founding in 1903. Hunters, furthermore, have been prominent since early days as well; Outside hunters headed through town on their way to Kenai Lake and the western Kenai gamelands, while Seward residents hunted on the outskirts of town and north within a few miles of the road or railroad. So far as is known, tourists and hunters prior to World War I largely ignored the southern reaches of Resurrection Bay, and virtually no recreationists spent time within the present park boundaries.

The first known recreational visit into park waters ended in tragedy. In October 1917, William G. Weaver and Benjamin F. Sweazey, the latter a licensed game guide, headed toward Aialik Bay on a bear hunt. When they did not return as scheduled, search parties were formed. Before long, the men's boat was found, bottom up, near Bear Glacier. No trace of the men was ever located. [56]

Over the next few years, a few Seward residents began to hunt in the coastal fjords. Charles Emsweiler, a local guide whose reputation was well established by 1913, took clients to the western peninsula gamelands. On his own, however, he hunted in a wide variety of locales, and in June 1919 he and his wife concluded a hunt in Nuka Bay, where they harvested three black bear. Three years later, the couple repeated their adventure. [57]

During the early to mid-1920s, occasional hunting parties–perhaps just one per year or even fewer–hunted within the present park boundaries. In May 1921, for example, local resident Jack Matsen headed down to Bear Glacier on what turned out to be an unsuccessful bear hunt. Two years later, the Gateway noted that "a party composed of Mrs. J. H. Flickinger, Andy Simons and wife, Frank Revelle and Milton Noll left today for down sound points where they will engage in a bear hunt." Occasional hunters also headed up into the Resurrection River valley; in August 1920, three Army privates ascended the valley at least as far as Redman Creek. [58]

Tourists–that is, recreationists who were not interested in hunting–were not known to frequent the present-day park until the mid-1920s. In August 1923, local residents Earl Mount and Mr. and Mrs. Otto Schallerer reportedly spent a pleasant Sunday on a boat "at the entrance to Resurrection Bay and at Bear Glacier." [59] So far as is known, no further pleasure trips to the park took place again until 1927. Captain Heinie Berger that year began operating his M.S. Discoverer between Seward and nearby points. In order to publicize his service and to create some community good will, Berger announced that for a mere $3, he would take local residents on a daylong scenic tour to Bear Glacier, Chiswell Island [sic], Seal Rocks, and Northwestern Glacier. The day set for the tour was Sunday, June 5. Poor weather, however, descended on Seward that day. The trip was cancelled, and the excursion was never rescheduled. [60]

For the remainder of the 1920s, and on into the 1930s, occasional tourist and hunting parties ventured into park waters. In 1927, for example, Seward police and fire chief Bob Guest headed off on "a sea voyage ... which will take in Seal Rocks and Nuka Bay." Two years later, a large party composed of the Seward Chamber of Commerce and their families cruised down the bay and got as far as Cape Resurrection and Bear Glacier before returning home. That same year, businessman Mel Horner shot a black bear at Bear Glacier, and in 1933 a Seattle physician named Frederick G. Nichols and his son spent almost two months in and around Nuka Bay engaged in fishing, hunting, and prospecting. [61] Nuka Island resident Pete Sather, the well-known Nuka Island resident, was glad to convey several of these parties. It should be noted, however, that Sather himself apparently found little enjoyment in the scenery that surrounded his daily travels. As Kenai Peninsula historian Elsa Pedersen has noted, Sather "did not notice the sure-footed mountain goats or the glossy black bears except as possible quarry for hunting parties he occasionally transported." [62]

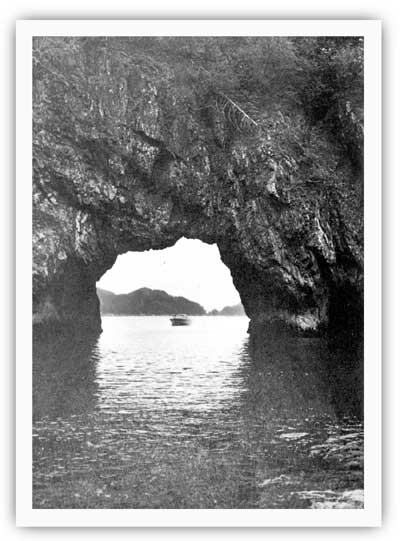

|

| The coastal littoral has long attracted a small corps of hunters on the lookout for mountain goats and black bear. Marilyn Warren photo, in Alaska Regional Profiles, Southcentral Region, July 1974, 147. |

In 1925, Seward witnessed a new form of recreational opportunity–aviation–that quickly put the previously inaccessible fjord and icecap country west of town within easy reach. That August, aviators Russell Merrill and Roy J. Davis flew from Anchorage down to Seward, and for the next several days the pair offered rides to all comers. The Alaska Road Commission, reacting to the growing popularity of aviation, roughed out an airfield in 1927-28, and in May 1928, Merrill and Davis "took three local passengers ... for a short flight over the bay and mountains." Aviation quickly caught on with Alaska's trappers, game guides and other outdoorsmen, but few tourists signed on, at least in Seward. [63]

Additional attempts to fly tourists took place during the 1930s, with mixed results. In 1932, Alaskan Airways began offering tourist flights from Seward to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. In all likelihood, few responded to this offer. The following June a new pilot, Art Woodley, began offering a series of flights out of Seward. The news article announcing his flights spared few adjectives in describing the surrounding countryside:

Seward, the Kenai ice cap and the marvelous scenic wonders of Resurrection Bay from the air is the temptation Pilot Arthur Woodley will toss to local residents Sunday when he will be prepared to provide a series of airplane flights beginning early in the afternoon, weather permitting.

The flights will be made in the handsome six-seated, 300-horse power Bellanca plane.... The flights will be divided into two divisions for local air excursions. Ten dollars will be charged for a cruise over the great eternal ice cap of the rugged Kenai Peninsula, from which vantage point the marvels of hundreds of miles of scenic grandeur will be unfolded from Prince William Sound to Cook Inlet.

There will be the lesser flight out over Resurrection Bay, with the broad Pacific laving the rugged shoreline, another treat of thrilling scenic wonders. For this flight a fee of $5 will be charged....

Lastly, there will be the Russian River fishermen's cruise, down where the 30-inch Rainbow trout sport in the crystal pools and challenging the angler. For this cruise a fee of $15 will be charged for the round-trip.

These cruises should have a strong appeal to all who have never beheld Alaska's scenic wonderland from the ethereal heights, from which to look down upon a world shedding its chaste garments of winter for the verdure of spring, its mighty glaciers and Brobdingnagian pinnacles reaching upward to greet the air-minded. [64]

Despite the favorable publicity, Woodley was unable to fly that day, "pea-soup weather" being the culprit. A few days later, however, the weather cleared. [65] His operation that summer evidently had some success, because he offered a similar variety of flights the following year. Three years later, John Littley established Seward Airways, which evidently lasted only a short time; two years later, Seward Airways, Inc. commenced operation. Neither of these carriers appears to have advertised scenic or recreational flights as a primary aspect of their operation. [66]

Recreational Trends, 1940-1970

The Kenai National Moose Range is Established

On December 16, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8979, which established the Kenai National Moose Range. The range reserved much of the western side of the Kenai Peninsula in order to ensure the preservation of the local moose population.

The movement to create a game range on the western Kenai had been a long time in coming. Back in 1904, when forester William Langille made his initial venture into the area, he was quick to note that big game was an important peninsula resource; moose, caribou, sheep, and bear were all noted. Langille noted that

the game of the region should be a source of revenue to the people and of pleasure and sport to the outsiders who wish to hunt, and there should be some meeting place where the game can be conserved, clashing interests harmonized and trophy hunting permitted. [67]

Nothing came of Langille's recommendations, but they were not ignored. In 1916, forester Arthur Ringland, worried about game poaching by trophy hunters, repeated those recommendations. [68] But the U.S. Forest Service had little intrinsic interest in game protection, and the issue lay fallow for more than a decade. During this period, the number of homesteads grew in both the Kenai and Homer areas. Increasing settlement, along with increased market hunting, caused federal authorities to worry about the permanence of the peninsula's moose population. In 1931, therefore, the Alaska Game Commission recommended, at its regular annual meeting, that an 800,000-acre (1,230 square mile) moose sanctuary, to be located in the northwestern part of the peninsula, be established by presidential proclamation. [69]

That recommendation, although not acted upon, set off a long-running investigation into the size and health of the Kenai moose herd. The Game Commission, using donated funds, dispatched guide Henry Lucas into the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area in 1932. Lucas discovered, due to Game Commission enforcement efforts, that the moose population was no longer declining; he also noted that local residents were firmly in favor of a moose sanctuary being established. The Game Commission, after studying the matter during a second field season, backed the idea of a moose sanctuary in the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area; that area, however, promised to be controversial because it was a prime trophy hunting area. Before long, the federal Bureau of Biological Survey promoted a competing plan, for a 500,000-acre moose sanctuary in the northern part of the peninsula (that is, in the same general area that the AGC had recommended in 1931). By 1934, interagency differences on the proposal had still not been resolved; this impasse had the practical effect of shelving any protection proposals for the time being. [70]

In the late 1930s, new worries about a perceived decline in the peninsula's moose population sparked another round of studies. Biologist L. J. Palmer spent the 1938 field season in the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area. He confirmed a long-term moose decline, but instead of a moose sanctuary, he recommended that the area be set aside as a moose and mountain sheep reserve. The area would be open to limited hunting, but closed to homesteading or other land location without special permits. He returned to the field that winter, and came back convinced more than ever that a moose range needed to be established. [71] Palmer's research provided the technical data necessary to justify the moose range idea; two years later, Ira N. Gabrielson applied the idea politically and established the moose range. Gabrielson, a leading conservationist, was the head of the newly established U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It was he who guided the proposal–a far grander proposal than Palmer had ever envisioned–through the agency and on to Roosevelt's desk. [72]

The Kenai National Moose Range, as enacted, covered some 2,000,000 acres. As stated in the proclamation, the range was established

for the purpose of protecting the natural breeding and feeding range of the giant Kenai moose on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, which in this area presents a unique wildlife feature and an unusual opportunity for the study in its natural environment of the practical management of a big game species that has considerable economic value.... [73]

Although the range was primarily established to protect wildlife habitat, its southeastern boundary followed the top of the Kenai Mountains drainage divide and covered more than 100,000 acres of the Harding Icefield. Tens of thousands of these acres, located high in the Kenai Mountains, are now part of Kenai Fjords National Park.

By the time President Roosevelt signed the Kenai National Moose Range proclamation, Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and World War II was at hand. Understandably, therefore, the range remained undeveloped for the next several years. It was not until 1948 that the first administrative facilities, at Kenai, were established. That September, David L. Spencer was appointed as the refuge's first manager; James D. Peterson was his assistant. [74]

Recreational Activities Along the Southern Coast

As has been noted (both in Chapter 9 and in a section above), commercial fishers and sightseeing parties were first lured to Resurrection Bay in the early years of the century and consistently used the resource in the decades that followed. The historical record is less forthcoming about Resurrection Bay sport fishing in the years prior to 1940. Most likely, sport fishing was a popular activity in and around Seward, and it may have also been part of early Resurrection Bay sightseeing activities.

After 1940 these trends continued. As Chapter 8 has noted, the military buildup prior to World War II brought thousands of soldiers to Seward's Fort Raymond and to the remote posts of Fort Bulkley (Rugged Island), Fort McGilvray (Caines Head), and similar installations scattered around Resurrection Bay. To cater to the soldiers' recreational needs, a variety of activities were organized. As early as April 1942, military authorities were sponsoring sightseeing and fishing excursions on Resurrection Bay. These seven-hour trips took place twice each week and appear to have continued, on a seasonal basis, through the summer of 1944. [75]

After the war, activity in Seward dropped off. But local officials, hoping to popularize the town, were buoyed by ongoing road development projects elsewhere on the peninsula and seized on those activities as opportunities to attract outsiders.

Several activities soon came to the fore. In 1950, before Seward gained its road link to Anchorage, local boosters began to advertise the traditional Mount Marathon race to out-of-towners. Five outsiders answered the call that year, and in 1951 a non-Seward resident won the race for the first time. During the mid-1950s, several nationally popular magazines noted the race in Alaskan feature articles. Over the years, the race attracted an increasing number of out-of-town contestants and their families. In recent years the Fourth of July race, and various associated events, have attracted thousands of participants and spectators each year. [76]

The road connecting Anchorage (and the rest of the Alaska road network) with the Kenai Peninsula was completed in October 1951. Soon afterward, residents from other communities began coming to Seward to fish and boat on Resurrection Bay. The number who engaged in such activities was at first fairly small. The migration was sufficiently large, however, to augment the fortunes of local businesses that sold licenses and gear, operated and coordinated charters, and processed fish. By 1953, sport fishing was sufficiently popular to attract the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the agency dispatched an enforcement patrolman, Joseph Widauf, to Seward for the silver salmon season. Widauf reportedly "did a very good job acquainting the sportsmen with the regulations and keeping violations at a minimum." [77]

In 1956, Sewardites took a major new step when the town hosted its first Silver Salmon Derby. The event was the brainchild of local residents Jim and Celia Wellington. Juneau, by this time, had been holding its salmon derby for more than twenty years, and the Wellingtons, former Juneau residents, borrowed the idea and brought it to Seward. The derby, sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce, was held on two successive weekends in August; the proceeds of the event were used to stock local streams with game fish and to finance other local improvements. The contest quickly caught on with both locals and out-of-town residents, and by the mid-1960s, "large numbers of sports fishermen [were harvesting] a high proportion of the silver salmon entering Resurrection Bay." [78]

Pleasure boating also grew during the 1950s. Soon after highway from Anchorage was completed, locals formed the Seward Small Boat Owners' Association to improve the facilities in the small boat harbor. Then, in March 1957, the Anchorage-Seward Yacht Club was founded to promote nautical recreation and to push for harbor improvements. The organization, renamed the Alaska Yacht Club, was incorporated in January 1958. The club, which by the 1970s was known as the William H. Seward Yacht Club, is still active. Over the years, the club has held many sailboat races; during the late 1960s, one of the more challenging races was the Summer Solstice meet, a 70-mile race that took contestants from Seward to the Chiswell Islands and back. [79]

With few exceptions (such as the boat races just noted), most of the boating and sportfishing activity that took place out of Seward from the 1940s through the 1960s was limited to Resurrection Bay. Very few boated or fished for pleasure in park waters. Known instances of such use are described below.

During World War II, the USO-SSO Activities Council (which organized recreational activities for soldiers) sponsored a series of boat trip outings, at least one of which entered park waters. In August 1944, it organized a free daylong trip to Aialik Glacier. Trips to other nearby features–Bear Glacier or the Chiswell Islands–may also have been sponsored during the war years. [80]

During the 1950s, the Fish and Wildlife Service wrote a special report on the Kenai Peninsula's fishery resources. The report noted that none of the bays or rivers in the present park ranked particularly high among the peninsula's sport fishing destinations. It did, however, state that in 1955, Resurrection River recorded 1,000 man-days of use by sport fishers, a volume that was exceeded by eleven other peninsula sport-fishing areas. [81]

In July 1961, the Bureau of Land Management classified hundreds of Alaska public land parcels as recreation and public purpose sites. These parcels, scattered throughout the state, were authorized by a Congressional act of June 14, 1926 and were available for disposal to "a state, territory ... or to a non-profit corporation or nonprofit association for any recreational or any public purpose." Within the present park boundaries, two parcels were classified by the BLM's action: a 900-acre parcel in the Bulldog Cove area, south of Bear Glacier, and an 80-acre parcel on the east side of Aialik Bay, just south of Coleman Bay. Available land records do not specify who may have been interested in the parcels, nor do they describe the parcels' intended land use. Lacking other evidence, it appears that the BLM probably offered the parcels to the State of Alaska. They were offered either to the Division of Lands for a future state park or recreation site or (less likely) to the Department of Fish and Game for fish management purposes. The interested party–whoever it was–soon learned that part of the Bulldog Cove parcel had previously been claimed by Raymond W. Gregory, who hoped to establish a fishing lodge on the property. Gregory, as it turned out, never developed his lodge plans, but the existence of his claim probably prevented the state from developing the site. Neither parcel was developed, and in January 1969 the two parcels were returned to the public domain. [82]

Sidney Logan, an ADF&G fisheries biologist, was posted in Seward in April 1961, largely due to the efforts of Seward Salmon Derby officials. In a recent interview, Logan recalled that Seward had four or five boats available for charter during the seven-year period he lived there; sportsmen normally did not fish farther south than Rugged Island, although they occasionally fished as far south as the Chiswell Islands. He noted that "hundreds of boats per summer visited the Kenai Fjords coast" during the years he lived in Seward. Logan was quick to point out, however, that "there was no sport fishing activity to speak of" in the fjords and that the amount of fishing was "insignificant" in comparison to either the Resurrection Bay silver salmon sport fishery or the Russian River sport fishery. Fishers sought out the waters of the future park for halibut, rockfish, and lingcod; so far as he recalled, no charter-boat operators consistently referred clients to locations in park waters. He did not recall any problems managing the park's sport fishery during this period. As to sightseers, Logan had no recollection of any; "there may have been some," he noted, "but I wasn't aware of it." [83]

Jim Rearden, who served as the Homer-based commercial fisheries biologist for ADF&G from 1960 to 1969, recalls that the waters of the future park supported much less activity than Logan had estimated. Rearden, who flew along the coast several times each year, stated in a recent interview that there were "virtually no sports fishermen" in the fjord waters during his tenure in that position. He recalled that the Seward boat harbor had "almost no sports boats before the [1964] quake" and that the waters in the fjords were too rough to allow sport fishing with the boats then available. [84]

Research by historian Mary Barry largely corroborates Logan's and Rearden's recollections. Barry noted that before 1960, Mark Walker's Breezin' Along was the only large boat in Seward available for fishing charters. (Several smaller boats also carried small numbers of paying fishermen.) During the early 1960s, there were approximately six charter boats; Jim Lawson and his wife started the Fish House during this period to coordinate fishermen and charter boats. The fishing fleet was largely wiped out in the 1964 earthquake, but a year later several charter boats were again available, the largest being the 83-foot Maxine, which carried 49 passengers. In 1968, a new company organizing fishing charters–Resurrection Bay Tours–commenced operations. Don Oldow, a veteran ship pilot, founded the company with his wife Pam. Beginning in 1974, the company began serving the fjord country. It thus played a key role in stimulating tourism to the fjord country, and it also assisted the NPS in its investigations of the proposed park unit. [85]

Ted McHenry, who moved to Seward as a sport fisheries biologist in 1969, recalls that there were "an odd few"–perhaps 20 boats per summer–that went into park waters during his first year or two of residence. Those few were operated primarily by Anchorage people who had "larger boats" moored at the Seward boat harbor. Most of those who sailed into park waters headed for Aialik Bay; others went to Harris Bay. McHenry felt that the boat owners, some of whom were veteran Resurrection Bay sports fishers, were attracted to park waters because they offered better opportunities to harvest halibut, salmon, rockfish, red snapper, black bass, and lingcod. [86]

If fishing and sightseeing were occasional activities in the future park during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, hunting appears to have been an even rarer activity. Little solid evidence has come to light regarding how much hunting has taken place. Prior to the mid-1960s, few sport hunters were willing to brave the fjord country's rough waters. Hunting pressure was slight for several reasons: the number of large mammals was relatively small, species such as Dall sheep and moose were unavailable, and the megafauna that inhabited the area–black bear and goats–could be harvested with less effort elsewhere. The only hunter known to frequent the outer coastal area during this period was Martin L. Goreson. Whether he hunted in the park is a matter open to debate.

Goreson, who hailed from New York, was one of hundreds of GI's who landed in Seward and served at Fort Raymond. After the war ended, he remained in town as a guard at the mothballed camp until October 1947, when the camp passed into private hands. Goreson then went into the guiding business, and in 1950 he heard about a Fish and Wildlife Service plan to transport goats from the Seward area to Kodiak Island. For two years, agency staff tried and failed to capture any goats; Goreson then stepped forward and volunteered. To the surprise of agency officials, Goreson was able to collect at least five mountain goats, more than enough to successfully initiate a Kodiak Island goat herd. [87] Several local wildlife experts have suggested that Goreson captured at least some of these goats within the boundaries of the present park. Available research, however, suggests that most if not all of his goat gathering took place either on the slopes of Mount Alice (northeast of Seward), near Day Harbor (east of Resurrection Bay), or at South Beach (near Caines Head). [88]

When a national park was being considered for the area in the early 1970s, the state (which favored the status quo) and the National Park Service (which backed a plan that would prohibit hunting) had widely divergent opinions on historical hunting levels. The state, citing the existence of an airstrip (built in 1965) at the head of Beauty Bay, noted that "the lands surrounding Beauty Bay have had a long history of seasonal use by hunters and fishermen because of ... its proximity to Homer." But NPS officials disputed that assertion and countered that "access [to the proposed park] for hunting is limited by the rugged terrain, weather conditions and general accessibility;" for that reason, "relatively few people would be affected" if a park was established. The agency noted that "the wild coastline and the lack of interest generally has kept sport hunting down. Harvest ticket counts ... show relatively low use." Citing ADF&G records for 1973, for example, the NPS noted that nine goat hunters had canvassed the coastline that year and bagged four goats. The NPS further noted that "only one full-time guide out of Seward hunts the fjord coast for mountain goat and black bear, the only two big game species represented in the proposal," and it was quick to point out that most of the guide's income was from non-hunting sources. [89]

In the Resurrection River valley, the NPS recognized that hunting opportunities were more favorable. A government report stated that "hunting of mountain goats also occurs [in the valley], where a few moose may also be taken." The state, however, closed the area along the newly constructed Exit Glacier Road in the early 1970s, probably to enhance wildlife viewing opportunities for tourists (see section below). It reportedly did so "at the request of the Seward Community who wished to encourage the viewing of unhunted wildlife in their natural habitats." [90]

Throughout the quarter-century that followed World War II, Seward itself was a relatively minor tourist draw. As noted above, the completion of the road to Anchorage made Seward accessible to rubber-tire travelers, and out-of-towners to an increasing degree flocked to Seward for the Fourth of July (for the Mount Marathon race and associated activities) and in August (for the Silver Salmon Derby). Except for those two events, however, the town had few tourist attractions. Seward promoters trumpeted that its Fourth Avenue had "the second brightest street in America" (only Chicago's State Street was brighter), and in the mid-1960s the town proclaimed itself the "Fun Capital of Alaska." Those claims, however, did little to change the town's overall perception; as a 1975 article noted, "When you mention Seward, most Alaskans think of a sleepy little town at the end of the highway." [91]

Oil Exploration and Kenai National Moose Range Management

One of the most significant events in Kenai Peninsula's history was the discovery of oil along the Swanson River, northeast of Kenai, in the summer of 1957. Because of the widespread period of oil exploration that preceded the find–and particularly because of the rush of activity that followed it–thousands of people descended on the Kenai, and thousands of acres of wilderness were converted to residential, commercial, and industrial purposes. Paradoxically, however, the only effect that this activity had on land in or near the present park was a blanket prohibition on oil and gas development. The following paragraphs explain how these developments were manifested.

As noted above, President Roosevelt had signed an executive order establishing the Kenai National Moose Range in December 1941. The range had remained intact and generally undisturbed during the war years; shortly after the cessation of hostilities, however, three privately-owned townships in the present Soldotna and Sterling areas were homesteaded and subsequently eliminated from the range. In 1947, a fire started by road workers destroyed 400,000 acres of wildlife and wildfowl habitat on the 2,000,000-acre range; on the heels of that fire, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service set up a headquarters for the range (in Kenai) and dispatched two men there to staff it. [92]

Before long, oil company representatives began to eye the range, and in 1952 seismic exploration began. Exploration, most or all of it taking place north of the Sterling Highway, continued at an increasingly hectic pace for the next several years, in large part because of the pro-development policies of Interior Secretary Douglas McKay. The frantic level of activity slowed in June 1956 when Fred Seaton succeeded McKay; Seaton halted any new oil and gas exploration until impact studies could be completed. But the pressure for development skyrocketed on July 23, 1957, when the Richfield Oil Company announced that one of its wildcat wells had struck a significant oil deposit more than two miles underneath a Swanson River moose pasture. [93]

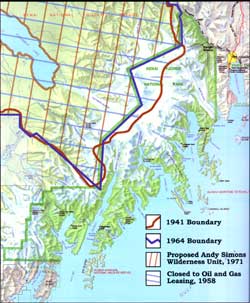

|

| Map 10-3. Kenai Moose Range Boundaries, 1941-1971. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Interior Department was soon inundated with requests that would have opened most of the Kenai Moose Range to oil-development activity. Congress reacted to the pressure by holding hearings in Washington because it wanted to know how the agency could simultaneously protect wildlife and permit petroleum development. Those hearings took place in December 1957. In the face of such development pressure, all the agency could realistically hope to do was shield a reasonable portion of the area from petroleum development. Secretary Seaton, therefore, decided in late January 1958 to close approximately half of the range to oil and gas leasing "because such activities would be incompatible with the management thereof for wildlife purposes." [94] Seaton, however, did not issue a Secretarial Order with that language until July 24 (see Map 10-3). The order declared that most of the range's southern half–including all of the land in the high-elevation country overlooking Skilak and Tustumena lakes–would be off-limits to oil and gas leasing. [95]

Pro-development forces, both inside and outside of government, demanded that Seaton open up more of the moose range to oil development. The agency, worried about a sharp drop in the area moose population, initially refused to budge. Eventually, however, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (part of the Fish and Wildlife Service) agreed on a land swap with the Bureau of Land Management and the Alaska Division of Lands. The various agencies agreed that the boundary realignment was "necessary in order to facilitate administration of the Range and as a basis for the survey of adjoining selections by the State of Alaska." The land trade entailed the removal of 310,000 acres of existing refuge land–most of which lay on the Harding Ice Cap and thus had low wildlife values–and added 40,115 acres of land in the Caribou Hills, adjacent to the refuge. On May 22, 1964, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall signed a Public Land Order that codified the land swap. The 270,000-acre reduction was not enough for the Alaska Congressional delegation, which attempted to eliminate another 270,000 acres. (Senator Ernest Gruening, part of the delegation, went so far as to urge that the entire moose range be returned to the public domain.) That move, however, was squelched, and the boundaries that were established in 1964 remained until the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in December 1980. [96]

The agency's early plans for the refuge (and in particular its plans for the Kenai Mountains portion of the refuge, adjacent to the present national park) were by necessity inseparable from the ongoing, petroleum-dominated political atmosphere. Agency officials nevertheless recognized that the range's ecological diversity demanded two different management objectives. Biologist Will Troyer, who wrote an early management document for the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (BSF&W), stated that the refuge had been created to "support large populations of moose, as well as quality trophy animals." The lowlands, he noted, were managed for high moose populations. The range also, however, had more than 500,000 acres of "spectacular mountain country" that the agency planned to manage for "trophy purposes and high quality hunting enjoyment." He recognized that nearly all hunting in the refuge took place in the lowlands. The managing agency, however, was also "obligated to manage a portion of this area for trophy animals," particularly of Dall sheep. [97] Because most hunting pressure took place in the lowlands, the agency had a largely laissez faire attitude toward the higher elevation areas of the refuge; so far as is known, it conducted no research projects in the highlands portion of the moose range.

During the 1960s and on into the 1970s, the BSF&W's management attitude toward the southeastern portion of the moose range remained consistently protective. In February 1960, for example, the agency released a recreational management plan for the refuge. The plan stated that "a management approach forcefully directed at a wilderness concept is required to preserve a resemblance [sic] of natural conditions caused by the inevitable forces of progress." The plan proposed numerous recreational improvements for the refuge, but none in the southeastern uplands. [98] In April 1971, the Fish and Wildlife Service released a wilderness plan for the refuge; it proposed more than a million acres of wilderness, including a huge Andy Simons Wilderness Unit encompassing all of the refuge's high country. (Simons, at noted above, was a famous, long-time guide who had died just a few years earlier.) [99] That plan was not implemented. Most of the acreage in the Andy Simons Wilderness proposal, however, became congressionally designated wilderness nine years later with the passage of ANILCA.

The Exit Glacier Road

As noted in Chapter 5, Seward citizens had been lobbying off and on since the 1920s for a road that would connect Seward to the Cooper Landing area via the Resurrection and Russian River valleys. Neither Federal nor state funding authorities had ever seriously considered these proposals. The completion of the Sterling Highway, and the connection of the Kenai Peninsula road network to Anchorage, largely negated the need to build such a road. But road-based tourism, which consistently increased during the 1950s and early 1960s, spotlighted the need to develop new area attractions, and the devastation wrought by the 1964 earthquake underscored the critical need to diversify Seward's economy. Herman Leirer, whose family had operated the local dairy since the mid-1920s, was acutely aware that far too many people "drove down the highway into town, then turned around and headed back because there wasn't anything to do." [100]

Leirer, Jack Werner, and other residents felt that "Resurrection Glacier," eight miles northwest of town, would be an excellent new sightseeing destination. In order to access the glacier, they decided to build a road there. By October 1965, they had convinced Seward City Manager Fred Waltz and the city council to take up the cause; they, in turn, organized a committee to complete the seven-mile access road. Many Seward residents, including some of the trainees at the local Skill Center, immediately set to work; the city helped by loaning them graders, loaders, and other equipment. Work continued until cold weather forced a cessation of activity. The following year, work was furthered by a grant from the Alaska Purchase Centennial Commission; efforts continued throughout the warmer months, primarily on weekends. [101]