|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 9:

COMMERCIAL FISH AND SHELLFISH HARVESTING

|

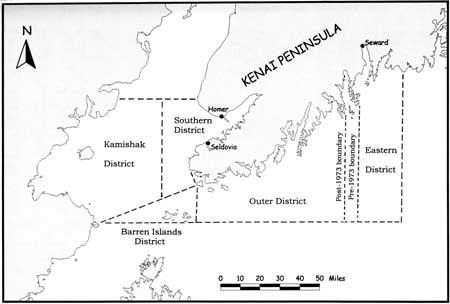

| Map 9-1. Historic Sites-Commercial Fishing. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Kenai Fjords coastline is rich with marine life. Many species of fish and shellfish inhabit the area's streams, fjords, and pelagic zones. Relatively few species, however, have been harvested for commercial purposes. Prior to the 1960s, the only species of interest to commercial fishers have been various species of salmon, halibut, cod, and herring. In recent decades, fishers have harvested a variety of new species, including species of crab, shrimp, scallops, and octopus. Halibut and cod, as a rule, have been harvested in the open ocean, 30 to 60 miles south of the park coastline, while the remaining fish and shellfish species have been gathered along or near the coast.

The streams of Kenai Peninsula's southern flank are shorter than those that flow into Cook Inlet. For this and other reasons, salmon (particularly red salmon) and other commercially viable fish and shellfish have never been as plentiful in this area as they have been either in Cook Inlet or Prince William Sound. Inasmuch as commercial fishing along the peninsula's southern coastline did not take place until fishing was a well-established industry in both Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound, the park's fishing history will be told within the context of developments in these adjacent areas.

This chapter will concern itself primarily with the area's commercial fisheries. A history of the park area's twentieth century subsistence fishery is described in Chapter 6, while the sport fishery is covered in Chapter 10.

The Southern Kenai Peninsula Salmon Fishery,

1911-1945

Not long after the United States government purchased Alaska from the Russian government, West Coast commercial fisheries interests began to exploit Alaska's untapped fisheries populations. They had, by this time, been harvesting the salmon populations of Washington territory and the province of British Columbia for some time. Before long, fishing companies began to eye Alaska's seemingly unlimited salmon resource.

Early Cook Inlet Salteries and Canneries

In 1878, Alaska's first two salmon canneries were established. Both were located in southeast: one was near Sitka, the other at Klawock, on Prince of Wales Island. That same year, commercial salmon interests first took advantage of Cook Inlet's rich fisheries resource; the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC), which operated a fur trading station near the mouth of the Kenai River, established a salmon saltery at the site. Captain James Wilson, the station agent, was in charge. A year later, a second salmon saltery was established at the Western Fur and Trading Company's fur trading station at the mouth of the salmon-rich Kasilof River, some 12 miles south of the ACC saltery. Captain H. R. Bowen operated both the trading station and saltery. During the same period, the first saltery was opened on Kodiak Island; it was located on Karluk Spit, along the island's southwestern coast. [1]

Other nearby fisheries developments followed soon afterward. In 1882, the first two salmon canneries in Central Alaska were built; the Alaska Packing Company of San Francisco built a cannery at Kasilof, while Smith and Hirsh built a cannery at Karluk Spit. The following year, the Alaska Commercial Company opened its second Cook Inlet salmon saltery; it was located at English Bay, where the company had operated a fur station since the early 1870s. [2]

Between the late 1880s and the late 1890s, new canneries were built in several areas adjacent to the southern Kenai coast. In 1888, four canneries were built on Kodiak Island and one at Kenai. A year later, the first Prince William Sound canneries were built (four were constructed there that year, all on the sound's eastern shore), and five additional canneries were erected on Kodiak Island. In 1890, a new cannery was constructed at Kasilof, and in 1897 another cannery arose at Kenai. In 1899, the first cannery was constructed on Cook Inlet's western shore; it was located at Tyonek. By 1900, therefore, scattered salmon canneries were located northwest, south, and east of the present park boundaries; all, however, were located more than a hundred miles away. During this period, the sockeye (or red) salmon was the only valuable salmon species; the early canneries, therefore, were located near sockeye-laden streams. Few were interested in the southern Kenai fishery, where pink and chum salmon species predominated. [3]

Few new canneries were constructed during the first decade of the twentieth century. The decade that followed, however, witnessed new growth in the fishing industry, and for the first time, canneries were constructed just a few miles away from the present park boundaries. In 1911, the Seldovia Salmon Company built the first cannery in Lower Cook Inlet; it was located at Seldovia, a town that had been in existence for more than 30 years. In 1912, the Fidalgo Island Packing Company built a cannery at Port Graham, and three years later a cold storage facility (for cod and halibut) was constructed at Portlock. Eight years later, the Arctic Packing Company built a cannery at English Bay. Seldovia and English Bay were long-established area villages; Port Graham and Portlock, however, were unpopulated sites before facilities were erected there. Canneries remained at most of these locations until the 1950s, if not longer. [4]

The Resurrection Bay Fishery

During the same period that witnessed the first canneries in Lower Cook Inlet, commercial salmon processing facilities were pioneered in Resurrection Bay. In 1911, Charles F. Boggs established a salmon saltery in Seward. Boggs, along with partner Alfred Rosness, operated the saltery in 1912 but closed it thereafter. [5] During 1915 and 1916 new salteries popped up on the east side of Resurrection Bay, at Caines Head, and at Sunny Cove on Renard Island; all were small in scale, and none lasted more than a few years. [6]

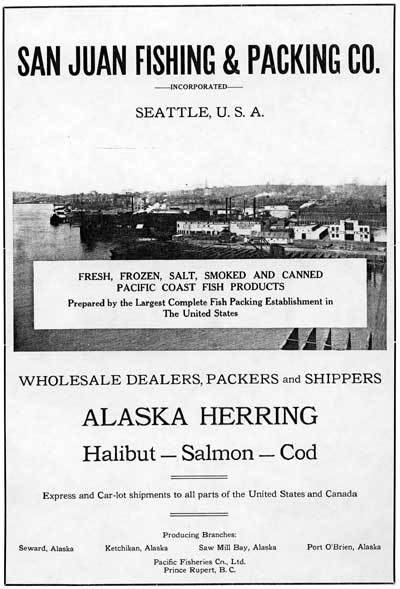

Canneries were also in the works. In 1912, former Seward resident Henry H. Hildreth headed a group that proposed a salmon cannery at Caines Head. The group also planned to construct a saltery at Porcupine Cove, recognizing that nearby Bear Glacier would be an excellent source for ice. But neither facility was built. [7] A more successful proposal was made by the San Juan Fishing and Packing Company. [8] Officials from that company arrived in Seward in November 1916; construction of a cannery and cold storage plant, located at the foot of Jefferson Street, began in January 1917. It was ready by the time salmon season commenced in mid-June. [9] Cannery management stated that in addition to canning salmon, they planned to freeze halibut, salmon, black cod and red snapper.

|

| The "San Juan plant" was Seward's largest cannery from 1917 to 1930. Pacific Fisherman Year Book, 1921, 104. |

For most of the next forty years, a salmon cannery operated in Seward. The so-called San Juan plant, using traps [10] as well as company-owned purse seiners, canned salmon only until 1921; for the rest of the decade, salmon was only an incidental part of an operation that was geared toward halibut processing. (Few black cod or red snapper were ever processed there.) Just a year after the San Juan plant de-emphasized its salmon canning operations, the Kodiak Island Fishing and Packing Company established a Seward plant. The cannery, however, operated for only the 1922 and 1923 seasons. [11] Fisheries interests were forced to conclude that the Resurrection Bay salmon supply was (in the words of one government report) "insufficient for the profitable operation of a cannery." In order to augment the salmon harvest, the Territory of Alaska built a hatchery at Grouse Lake (eight miles north of Seward) that opened in late 1924. Red, king, and pink salmon were raised. A fire, however, destroyed the hatchery in March 1927. It was not rebuilt. [12]

In 1929 a new plant, called Seward Fisheries, Inc., appeared on the scene. Owned by Nils Hagen and three associates, it was located just south of town and was described as a "smaller fish-processing plant;" fish were butchered by hand but packed by machine. The facility operated until 1934; it then lay idle for two years until it was reopened as the Hagen and Company plant. The new, improved plant was fully mechanized; government observers, however, noted that the facility was still just "a small one-line cannery." [13] The Hagen and Company plant operated until the end of World War II. [14]

When the San Juan plant opened in 1917, officials had announced that even though the company had three purse seiners, it would process all fish delivered to the plant. Such an invitation, which was tendered by canneries throughout the territory, encouraged the growth of a local, independent fishing industry. Before the San Juan plant opened, Seward-area fishers were probably limited to those who were involved in the early salteries (noted above), plus occasional entrepreneurs who sold their catch directly to local residents. The presence of a cannery, however, attracted a sufficient number of Seward-based fishing vessels that by the late 1920s, the Federal government had agreed to construct a small boat harbor. The Corps of Engineers constructed the harbor during the summer of 1931. [15]

|

| Boats based at the Seward small boat harbor (such as those moored in this mid-1970s view) have played a major role in the fishing history of the nearby fjords country. M. Woodbridge Williams photo, NPS/Alaska Area Office print file, NARA Anchorage. |

The number of fishing vessels, never large, varied from year to year; in 1933, for instance, the Seward Gateway noted that the local fleet consisted of the M.S. Marian, the M.S. Roy, the M.S. Mayflower, the M.S. Bavaria, and several power dories. (The first four motor ships were independently owned; Seward Fisheries owned the dories.) Henry Munson, a longtime local resident, recalled that during the 1930s "there were about a dozen boats fishing in the bay;" a wartime report concurred with Munson's estimate, noting that "about 12 fishing boats are normally based in the Seward harbor." [16] During the early years of the fishery, the primary techniques used were either beach seines or hand purse seines. By the mid-1920s, however, these methods had been replaced by gill nets; during the 1930s, gill nets and power dories harvested the bay's fish. The summer fishing season typically began in early June and lasted until August 10; the fall season began ten days later and stayed on until September 10. [17]

The Regulatory Environment

Early Alaska salmon processing was carried on in a virtually laissez-faire environment. But by the early 1920s, it had become increasingly clear that commercial interests had overfished and abused many of Alaska's primary salmon fisheries. Governmental authorities, as a result, began to regulate some of the territory's prime salmon fishing areas. The first such action took place in 1922 when three fisheries reservations were established; one of the three, the Southwestern Alaska Fisheries Reservation, included waters just west of the southwestern Kenai Peninsula. The following year, more widespread changes began. The U.S. Bureau of Fisheries subdivided the territory into management districts; the area west of Gore Point was included in the Cook Inlet district, while the area east of Gore Point was included in the Prince William Sound district. [18] The reservations created in 1922 remained in force until June 6, 1924, when Congress passed the so-called White Act. This act established a framework for regulating each of the territory's fisheries; areas undergoing considerable fishing pressure, predictably, were immediately regulated with closures and other management actions, while areas that were seldom fished were given few regulations. [19]

In Cook Inlet, several canneries were in operation each year during the 1920s and 1930s. In response to the high degree of fishing activity, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries applied increasingly sophisticated management actions. Beginning in 1923, for example, the agency dispatched the patrol boat Teal from its Seattle headquarters to the Cook Inlet fishing grounds; the Teal remained in the inlet all summer, gathering information and enforcing fishing regulations. By the end of the decade, the government was sponsoring an ongoing stream improvement program along selected Cook Inlet waterways. Before long, the agency began to deploy stream guards at key Inlet locations to enforce fishing regulations, and by the late 1930s it had begun chartering aircraft to augment the existing patrol efforts. [20]

|

| During the mid-1950s, the Fish and Wildlife Service placed stream guards near several area streams. This 1958 photo shows a typical stream guard shack, skiff, and a Coast Guard floatplane. USF&WS, Cook Inlet Annual Management Report, 1958, 127. |

In Resurrection Bay, where fishing activity was substantially less than in Cook Inlet, the regulatory environment was more relaxed. As noted above, Resurrection Bay was first considered to be part of the Prince William Sound management district. In December 1924, revised White Act regulations redefined Resurrection Bay as being a separate management district with its own set of regulations; the district's fish volume, however, was so small that Central District (Prince William Sound) personnel in Cordova reported on Resurrection Bay fisheries activity. The bay became an administrative part of the Cook Inlet district in early 1951 and has remained there ever since. [21]

Fisheries management in Resurrection Bay was applied with a much lighter touch than in Cook Inlet. Specific regulations, for example, were applied only to bay waters that were north of an imaginary line connecting Cape Resurrection and the west side of Bear Glacier. Active management measures were few. In 1931, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries dispatched a stream guard to the bay; a year later, the agency maintained a salmon weir near Bear and Grouse lakes. The Teal, however, seldom visited Resurrection Bay; the stream improvement program was virtually nonexistent; and fisheries personnel rarely if ever engaged in aerial patrols. [22]

Fishing Along the Outer Coast

Prior to the end of World War II, the long stretch of coastline between Resurrection Bay and the southwestern tip of Kenai Peninsula was almost entirely ignored by the commercial salmon industry. The primary reason for the lack of interest was that red (sockeye) and king (chinook) salmon were the only varieties sought by the canneries. The southern coastline's annual yield of these species was insignificant during this period; the sockeye runs were much smaller than those of later years, because glaciers and floating glacial ice then covered many areas that are now ice-free. [23] The severe weather, rough seas, remoteness from a fisheries facility, and the comparative fragility of the fishing boats then in use were additional reasons why fishers generally avoided the area.

The outer coast, beginning in 1923, was classified as being part of the Prince William Sound district. Then, in late 1924, the area became part of the new Resurrection Bay district. Fishing pressure along the outer coast, however, was so light that no specific regulations were applied to the area until after World War II. By the 1930s, the coastline had once again come under the nominal purview of the Prince William Sound district fisheries agent. That person, however, had far more pressing management concerns; he generally ignored this stretch of coastline, both in day-to-day activities and in annual reports. By 1943, the stretch of coastline west of Aialik Cape had become an administrative division of Cook Inlet. It has remained there ever since. [24]

Governmental fisheries officials, for the most part, were convinced that this stretch of coastline was essentially bereft of marine resources. One report, based on 1927 data, noted the following about the area:

The fishery districts nearest to [Resurrection Bay] are Prince William Sound on the east and Cook Inlet on the west. In both directions [from Resurrection Bay], especially to the westward, are miles of coastal waters that have no salmon fisheries, so that this bay stands as a district wholly apart from any other.... [25]

Despite that assessment, however, there is widespread evidence that commercial fishers periodically harvested fish from park waters prior to World War II. Evidence is strongest for such activity during the 1930s and early 1940s, although commercial fishing boats may have been active in the area during the 1920s as well.

As noted in Chapter 6, Natives from English Bay and vicinity often traveled along the park coastline as part of their seasonal round during the years prior to World War I. The establishment of canneries at Seldovia, Port Graham, and English Bay during the 1911-1920 period had the practical effect of disrupting the Natives' seasonal cycle; cannery work was available during the months when residents traditionally put up salmon for winter supplies. [26] Prior to World War I, therefore, Natives were the primary (perhaps the only) subsistence fishers along the outer Kenai coast; whites avoided the area (in the words of one longtime resident) because they "didn't want to step on the toes of the Natives." But after the war, there were "lots of white fishermen" and relatively few Natives. Some of those white fishers may have been residents of Halibut Cove or other Lower Cook Inlet communities who traveled the coast on their way to the Prince William Sound fishing grounds; residents of Cordova and vicinity may also have fished the coastline on their way to Cook Inlet. [27]

Specific information about who fished (or just traveled) along the coast has been provided by Josephine Sather, who helped run a fox farm on Nuka Island. Sather, writing in the mid-1940s, spoke kindly of several "old timers who [came] here on their regular seasonal trips." They included John Malutin, Hans Simondsen, and Bert Jacobsen. Malutin, a Seward resident, was captain of the M.S. Marian, which was active from 1927 to 1933, perhaps longer. Little is known about the other two fishermen. In all probability, the Kenai coast was probably visited by quite a number of fishing boats during the 1920s and early 1930s. Because the coast yielded few if any kings or sockeyes, however, commercial fishers did not linger in the area for long. [28]

As noted in Chapter 6, Pete and Josephine Sather were the best-known people to fish the park's waters during this period. They caught pink salmon with seines in many areas of Nuka Bay, and most of the time they were subsistence fishers, feeding what they caught to their foxes. Pete, however, occasionally attempted to sell pink salmon at the canneries, despite their relatively low value. One old-timer recalled that if Sather and other locals "could sell their fish for one-quarter cent each, that gave them flour and sugar for the winter." [29] Sather would typically fill his boat to overflowing; then, because his fishing boat had no refrigeration equipment, he would often head west to the Port Graham-Seldovia area, hoping for a quick sale. If the first cannery he visited wouldn't buy his fish, he would move on to other canneries, making offers at each one. Sather also sold his harvest at the Seward canneries; according to Ralph Hatch, a longtime resident, Sather made a couple of heavily-loaded trips per year to off-load pinks. "By the time he got here," Hatch recalls, "the boat smelled bad but the cannery took them anyway." [30] It should be noted that while much of Sather's subsistence fishing was from Nuka Bay, some–perhaps most–of his commercial fishing harvests were probably from Port Dick and other westward waters. [31]

East of Nuka Bay, the only park waters known to be fished before World War II were located at the southwestern end of Resurrection Bay. In all probability, Seward-area fishers discovered not long after the San Juan plant commenced operations that the Bear Glacier area offered a significant fish run. By the early 1930s, Resurrection Bay had two distinct sockeye runs. The first and larger run took place in the upper bay (north of Caines Head) in early June. By the end of the month, however, the local newspaper announced that "The salmon run in [upper] Resurrection Bay is about over and vessels will have to journey down to Bear Glacier if they expect to make any catches, say local fishermen." [32]

West of Nuka Bay, little or no commercial fishing took place anywhere along the outer coast during the early to mid-1920s. The English Bay, Port Graham, and Seldovia canneries obtained their fish either from nearby fish traps or from fishing boats that stayed fairly close to home. Beginning in 1928, however, a new cannery was built in Portlock, 12 miles southeast of English Bay, and a larger facility was constructed there in 1930. The new Portlock cannery, the availability of more seaworthy fishing vessels, and most of all the rising value of pink salmon all resulted in the exploration of the fishing resources of Windy Bay, Rocky Bay, Port Dick, and other outer coast sites. Fishers soon discovered that these bays were rich in pink and chum salmon, and as the price of these fish rose, these areas became increasingly attractive to the nearby canneries. Roy Cole, the captain of the patrol boat Teal, noted in 1935 that "a few [pinks] show in the lower Inlet from English Bay to Point Gore." By mid-July of that year, commercials fishers were harvesting pinks and chums in Port Dick and selling their harvest to the Adriatic, a tender owned by the Cook Inlet Packing Company plant in Seldovia. [33]

|

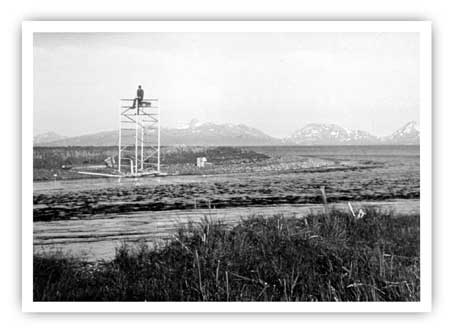

| During the 1920s, Seward was a popular stopover for ships in the halibut fleet that fished out on Portlock Bank and area sites. Neville Public Museum, photo 5670.4. |

Little is known about fishing activity in the western part of the outer coast for the next few years; management reports from the period do not discuss the subject. [34] Nevertheless, pink or chum salmon (perhaps both) probably continued to be harvested, though in small volumes. By 1939, the area was once again receiving Captain Cole's attention; he noted that year that "the run of pinks in the section from Point Gore to Seldovia was scattered" and made a specific description of the Port Dick run. In 1940, he noted that "intensive fishing was in progress" between Seldovia and Port Dick from July 28 to August 10; the following year, Cole noted a "very good" pink run along the coast between Kachemak Bay and Port Dick and "intensive seine fishing" in the Port Dick area in late July and early August. The resource was sufficiently valuable that Cole, and the Teal, personally monitored the Port Dick seine activity during this period. By the early 1940s, therefore, the fishing resources west of Gore Point had been fully explored and were being commercially exploited on a regular basis; Port Dick, specifically, was being described as one of two major pink producing streams in Lower Cook Inlet. [35]

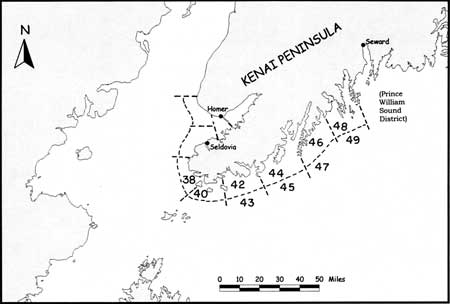

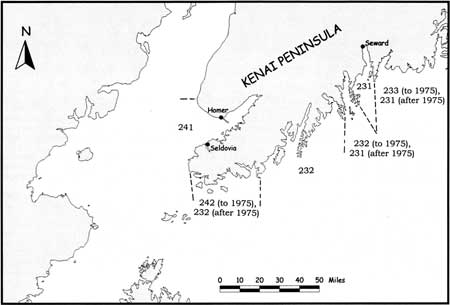

By 1943, commercial fishers had made the first known foray into the Kenai Fjords area. The management report that year noted a new "Seward District" that year east of Port Dick; that district was composed of "Seward Bay" (Resurrection Bay?), from which 7,330 pink salmon were harvested, and "Tunder Bay" (Thunder Bay?), from which 11,970 pinks were harvested. The harvest for both bays was minor; together, they accounted for just 2.1% of the 900,000-plus pink salmon that were caught that year on the east side of Cook Inlet. [36] The "Tunder Bay" harvest did not immediately result in further commercial activity. By 1944, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the successor to the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries) had instituted a statistical system that recorded the number of fish caught along specific segments of coastline (see Map 9-2). That system failed to record a commercial fish harvest between Gore Point and Aialik Cape either in 1944 or 1945.

|

| Map 9-2. Southern Kenai Peninsula Statistical Areas, 1944-1950. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Although fisheries reports suggest (admittedly, with some lack of certainty) that 1943 was the first year of commercial activity in park waters, several longtime Seward residents recall that local fishers (other than Pete Sather) worked in park waters before 1943. Henry Munson, whose memories of Seward date back to the mid-1930s, recalls that "boats went beyond Resurrection Bay" during that period and that "there were boats in that area before World War II." Seward Shea, another longtime resident, was more specific; he remembers stories of salmon fishing at the south end of "Pete's Island" (Nuka Island) and also near Petrof Point. In Shea' s recollection, the boats in this area came from Seldovia; he admits, however, that never personally saw a Seldovia or Port Graham boat east of Gore Point during this period. [37]

Salmon Fishing Along the Southern Kenai Coast,

1946-1959

General Postwar Trends

During the decade following World War II, the number of canneries in lower Cook Inlet remained stable. As they had for the previous two decades, canneries active west of the park were located at Portlock, Port Graham, and Seldovia. East of the park boundaries, the "small, one-line cannery" in Seward changed its name in 1946 (from Hagen and Company to the Resurrection Bay Company), and it changed its ownership in 1950 (from Nils Hagen to Marvin Viale). The cannery, however, continued to operate much as it had since 1937, when the plant had become fully mechanized.

Major changes took place in the area's salmon industry during the postwar period. One discouraging trend was that fishermen, particularly in Resurrection Bay, were overharvesting reds and other salmon species. (In 1947, a Seward entrepreneur backed away from a fisheries venture because he considered "the runs in Resurrection Bay to be too nearly depleted;" the area fisheries agent that year agreed, declaring that the bay's chum run was "used up." [38]) The Seward cannery, desperate to obtain enough fish to sustain operations, began purchasing Copper River salmon, even though (in the government agent's opinion) "some of these fish were, no doubt, taken illegally in [Prince William] Sound...." This practice was already underway by 1944 and continued for several years thereafter. [39]

A second postwar trend that affected canneries was the statehood movement. Prior to World War II, few Alaskans pushed for statehood. The war, however, brought thousands of new residents, an enhanced defense capability, and less dependence on resource-based industries. The canneries were one of the primary interests fighting statehood, but statehood advocates fought back and cited the widely used fish trap as a primary instrument preventing locally-based resource development. The territorial legislature, and Alaska's delegates to Congress, put increasing pressure on the canneries to eliminate fish traps. The canneries stubbornly hung on; they did not abandon fish traps until 1958, the year Congress passed the statehood bill. The continuing pressure, however, resulted in a reduction in the number of fish traps during the 1940s and early 1950s. This de-emphasis on fish traps took place in Lower Cook Inlet, as elsewhere; in order to keep harvest levels at previous levels, more fishing boats were deployed and boats searched ever farther for salmon stocks.

The overharvesting of the red salmon resource (on a territory-wide basis) and the increasing acceptance of pink salmon as a food fish resulted in higher pink and chum salmon prices. That price structure made Port Dick (which during some years was the Cook Inlet district's most highly-productive pink salmon harvest area) and nearby bays increasingly attractive fishing venues. The new price structure, combined with the increasing scarcity of red salmon, also encouraged independent fishers to seek out previously untapped areas. The windswept, stormy stretch of coastline between Gore Point and Resurrection Bay had, as noted above, been only lightly utilized prior to the mid-1940s. During the next decade, however, an increasing number of fishers explored the area for the first time.

Fishing in Park Waters: The Laissez Faire Period, 1946-1954

The first postwar harvesting of park waters took place in 1946 in Statistical Area 44 (see Table 9-1). This stretch of coastline runs between Gore Point and the Pye Islands; it encompasses both Nuka Bay and Nuka Island. Fish and Wildlife Service records indicate that 2,513 pinks and 75 chums were caught there that year; the number of pinks was some 0.3 percent of the Cook Inlet total, while the chum harvest was less than 0.1 percent of the total number caught in the Cook Inlet district. Records do not indicate specifically who caught these fish. It appears, however, that Pete Sather, who worked that year as an independent purse seiner for the Resurrection Bay Company, harvested a majority of the pink salmon and almost all of the chums in that area. (Sather also worked elsewhere, most probably in the Port Dick-Windy Bay area.) [40]

Table 9-1. Harvest Data for Statistical Area 44, 1944-1950

In 1944, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service divided the Cook Inlet Management District into statistical harvest areas. Six statistical areas comprised the waters of present-day Kenai Fjords National Park. Area 44 included the inner waters from Point Gore to the Pye Islands; Area 45 included the outer waters in that area. Area 46 included the inner waters from the Pye Islands to the east side of Two Arm Bay, Area 47 the outer islands. Area 48 included the inner waters from the east side of Two Arm Bay to Aialik Cape, Area 49 the outer waters.

For Area 44, which included the waters surrounding Nuka Island and the waters of Nuka Bay, the harvests in the following table were recorded from 1944 through 1950. For areas 45 through 49, the Fish and Wildlife Service tabulated no harvest during this seven-year period. The agency did not provide data for these areas after 1950.

NOTE: "% of CIH" is the percentage of the total Cook Inlet harvest (for that species) that was caught in Statistical Area 44.

| Pink Salmon | Chum Salmon | Coho Salmon | ||||

| Number | % of CIH | Number | % of CIH | Number | % of CIH | |

| 1944 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1945 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1946 | 2,513 | 0.3 | 75 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1947 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1948 | 7,918 | 2.1 | 109 | 0.1 | 52 | 16.2 |

| 1949* | 36,761 | 8.5 | 5,200 | 2.2 | 37 | n.a. |

| 1950 | 1,760 | 0.8 | 1,857 | 5.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

* - The 1949 total includes 151 reds. The harvest total includes 6,891 pinks reported in the Cook Inlet report; the remaining harvest, which came from "Nuka Bay," was processed by the Resurrection Bay (Seward) cannery and was reported in the Central District (Prince William Sound) report.

Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Cook Inlet Annual Management Report, various issues.

In 1947 no commercial harvests were recorded in park waters, perhaps because even-year runs in adjacent areas had proven to be far stronger than odd-year runs. The following year, however, commercial fishermen returned to Area 44 and harvested 7,918 pinks, 109 chums, and 52 cohos. Although Pete Sather may have harvested a portion of the area's catch, the only known fisher there that year was Alfred A. Anahonak, a 30-year-old "private operator" (that is, an independent fisherman) from Port Graham. Anahonak's possession of a fishing boat represented a new trend among area residents. Subsistence expert Ronald Stanek has noted that before World War II, residents were "limited to set netting, working for the canneries, and utilizing wild resources for subsistence purposes. Since then, Port Graham fishermen have acquired their own drift and seine boats...." [41]

In 1949, fishers again ventured out to Area 44 and gathered far more fish than they had in previous years. Fish and Wildlife Service figures indicate a total harvest of 36,761 pinks, 5,200 chums, 151 reds, and 37 cohos. The Area 44 pink harvest that year was a surprising 8.5 percent of the Cook Inlet total; the chum haul was large too, totaling 2.2 percent of the Cook Inlet catch. The harvest was notable for another reason; it was the first year that a red salmon harvest had been recorded in the area. In 1950, fishers returned to Area 44 and harvested 1,857 chum salmon (5.2% of the Cook Inlet chum catch) along with 1,760 pink salmon. Commercial fishers, it appeared, had "discovered" the park's waters. The only park area in which fishers had shown an interest, however, was Area 44 (west of the Pye Islands), along with the Bear Glacier area. [42] The long stretch of coastline between McArthur Pass and Aialik Cape was still untouched.

During this period, "Herring Pete" Sather (according to admittedly inexact records) spent much of the fishing season working in the Port Dick area or in other areas outside park waters. Others, therefore, fished the Nuka Bay area to an increasing degree. Alfred Anahonak, noted above, was one early harvester. Others may have been a quartet of Seward fishers named Bill Bern, Glen Hammersly, Freddy Blosso, and Charles Peterson. According to Seward Shea, a longtime Seward resident, the four men worked on the purse seiner Marathon. One day, "Herring Pete" told them that the fish were jumping in Nuka Bay. The bay at that time, however, was a hazardous place to reach; McArthur Pass was often impassable because floating ice was dangerous to the wooden boats then in use. Because the McCarty Glacier face was not far north of James Lagoon, additional ice lay in the southern reaches of Nuka Bay. Despite those dangers, the four successfully fished the bay, and their success brought others in their wake. [43]

As noted above, 137 red salmon were harvested in Area 44 in 1949. This harvest, small though it was, was significant inasmuch as these were the first red salmon caught in park waters by commercial fishers. The existence of a red salmon population in the bay indicated that the glaciers had retreated enough to support a biologically active lake-and-river system where reds could spawn and migrate. The McCarty Glacier face, during the early years of the century, had connected James Lagoon on the west with McCarty Lagoon on the east; and to the north, the upland areas on both sides of the glacier were glaciated as well. Between 1920 and 1925, however, the glacier's eastern side had melted to the point that Delight Lake was formed, and between 1935 and 1940 a new water body, Desire Lake, emerged to the north. If it is assumed that the red salmon harvested in 1949 came from the Delight Lake system (the most logical location for them), then the time lapse between the lake's emergence from the ice and its ability to support a red salmon run was less than thirty years. This is a remarkably quick recovery, considering the biological complexities involved. [44]

Another sockeye run that began during this period took place in Aialik Bay. Longtime resident Seward Shea recalls that the run, which spawns in Addison Lake above Pederson Lagoon, was discovered by Seward resident Henry Larson, known locally as "Henry the Bear." In either the late 1940s or early 1950s, Larson entered the bay in search of platinum float. He built a small prospecting shack and used it as a base camp. His prospecting venture failed but he found salmon by the hundreds. Using a gill net, which he stretched between an island (perhaps Slate Island) and the mainland, he harvested $6500 worth of sockeyes. Soon after Larson returned to the dock, news of the find spread to Shea and other Seward fishermen. Many of the other fishers made their own investigation and returned there in later years. Government fisheries agents, however, did not learn about the Aialik red run until the late 1950s. [45]

Pete Sather, a Nuka Island resident since the mid-1920s, not only fished Nuka Bay's salmon, but as an incident during the early 1950s shows, he claimed to have single-handedly started a run of his own. As part of his fox farming operation, he consistently cleaned the pink salmon he harvested in a stream that previously, in Sather's opinion, had had no salmon in it. (This stream was probably adjacent to his cookhouse, which was not far from his residence.) By the early 1950s, the stream supported a significant pink salmon population. Other fishers discovered the run and attempted to harvest the resource. Pete, however, resisted; he reasoned that he had single-handedly created the run and should therefore have proprietary rights over the salmon. He took his case to the courthouse in Anchorage; the court, however, ruled against him. [46]

As noted above, management of park waters during the late 1940s was ostensibly under the purview of the Cook Inlet District. The small harvest level, however, incited no interest from federal fisheries authorities; they may have ignored the area because, to some degree, the park's waters were being fished out of Seward, which was in the Central (Prince William Sound) District, headquartered in Cordova. In early 1951, management of the Resurrection Bay fishery shifted from the Central District to the Cook Inlet District. For the next several years after that boundary change, annual reports continued to overlook fishing activity in park waters. (Jim Branson, who worked as a Fish and Wildlife Service stream guard at Port Dick in 1952, perhaps summed up the agency's attitude toward the area when he mentioned, in a recent interview, that the agency ignored the coast east of Gore Point because there was "not much of a resource out there.") In all probability, a small number of commercial fishermen continued to venture to Nuka Bay, [47] but as one old-timer noted, "population levels [of fish were] hammered there because there was no enforcement." Fisheries managers continued to ignore the area until 1953, when "numerous air and foot surveys were conducted in the lower inlet...." That effort, which included "all important pink and chum streams south of Kachemak Bay," included a cursory survey of Nuka Island streams. Fisheries personnel probably ignored other Nuka Bay sites. [48]

As noted earlier, one of the two major reasons that Nuka Bay and other pink- and chum-producing areas became popular between the late 1940s and the mid-1950s was because of increasing price levels. Before 1940, prices for the two species were so low that they were incidental fish; that is, they were caught by fishers who were searching for other, more highly valued species. By 1942, the price of the two species had risen to 6-1/2-8-1/2 cents apiece; five years later, pinks sold for 11 cents while chums sold for 15-1/2 cents. Based on those prices, Cook Inlet canneries typically processed 40,000 cases of pinks and 30,000 cases of chums each year. But after 1950, prices on both species rose substantially; in 1952, for example, pinks sold for 30 to 40 cents apiece while chums were worth 40 to 50 cents. As a result, fishing boats sought to catch an increasing number of pinks and chums during the 1950s. [49]

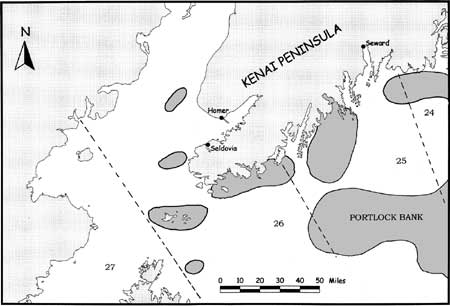

Rising price factors, however, do not fully explain why interest in the Nuka Bay area skyrocketed in the mid-1950s. The other causative factor was availability. Statistics from Cook Inlet show that during the 1946-1951 period, both total catch levels (expressed in number of fish) and fishing effort (expressed in gear-unit days) rose steadily. From 1951 to 1957, however, both of these figures declined. It became increasingly clear that the streams that had traditionally provided large pink salmon returns–the Talachulitna River (a tributary of the Susitna), the Kenai River and other streams flowing into the northern and central portions of Cook Inlet–were being overharvested. As a result, canneries eagerly sought out alternative locations. The Outer District, which stretched from Point Adam (near Portlock) to Aialik Cape (see Map 9-3), contained many productive pink and chum runs; not surprisingly, therefore, the park waters and other Outer District streams became increasingly important during this period (see Tables 9-2 and 9-3). Based on the contributions of Outer District streams and those in other newly-harvested locations, the volume of fish caught in the Cook Inlet administrative district rose again by the late 1950s and continued to rise for years thereafter. [50]

|

| Map 9-3. Lower Cook Inlet Management Districts. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Table 9-2. Outer District (of Cook Inlet) Salmon Harvest, 1954-1995

Figures given are number of fish, while percentages are those of the entire Lower Cook Inlet catch. The Outer District goes from Point Adam (south of Port Graham, on Kenai Peninsula's southwestern tip) to Bear Glacier (at the southwestern end of Resurrection Bay). Source: ADF&G, Cook Inlet Finfish Report, 1976-1977, Table 16; and ADF&G, Lower Cook Inlet Finfish, Annual Management Report, 1995, Appendix Table 8.

An asterisk (*) signifies a percentage less than 0.1%. In regards to king salmon, a number sign (#) is used because no attempt was made to compute percentages. The number of kings harvested is relatively small; the number harvested in all of Lower Cook Inlet has never exceeded 2,000 per year, and in most years commercial fishers harvested fewer than 500.

| Year | Kings(#) | Reds | Cohos | Pinks | Chums | Total |

| 1954 | 13 | 4,927 (12.4%) | 369 (2.4%) | 82,205 (30.6%) | 112,877 (42.5%) | 200,391 (33.8%) |

| 1955 | 7 | 701 (1.7%) | 277 (2.9%) | 557,997 (47.1%) | 40,887 (59.5%) | 599,869 (46.1%) |

| 1956 | 23 | 2,889 (8.0%) | 190 (2.0%) | 42,368 (20.4%) | 19,248 (21.8%) | 64,718 (18.9%) |

| 1957 | 13 | 2,982 (11.1%) | 110 (6.2%) | 149,197 (52.2%) | 138,171 (66.9%) | 290,473 (55.7%) |

| 1958 | 1 | 1,719 (8.8%) | 83 (4.6%) | 739,768 (77.9%) | 100,386 (80.6%) | 841,957 (76.8%) |

| 1959 | 3 | 10,365 (47.9%) | 109 (1.7%) | 68,875 (55.2%) | 65,675 (59.3%) | 145,027 (55.0%) |

| 1960 | 4 | 1,336 (5.4%) | 533 (19.8%) | 328,501 (53.7%) | 67,187 (57.9%) | 397,561 (52.6%) |

| 1961 | 2 | 12,595 (55.3%) | 444 (27.4%) | 105,447 (34.8%) | 40,204 (72.3%) | 158,692 (41.4%) |

| 1962 | 2 | 8,697 (34.4%) | 1,893 (24.5%) | 1,684,023 (74.9%) | 126,750 (70.7%) | 1,821,365 (74.0%) |

| 1963 | 6 | 1,974 (13.1%) | 369 (5.5%) | 21,462 (10.6%) | 116,923 (84.4%) | 140,734 (38.7%) |

| 1964 | 2 | 1,370 (6.6%) | 431 (4.6%) | 767,396 (72.7%) | 269,512 (83.4%) | 1,038,711 (73.7%) |

| 1965 | 0 | 1,965 (14.0%) | 7 (0.8%) | 21,816 (18.9%) | 22,443 (79.9%) | 46,231 (29.2%) |

| 1966 | 1 | 2,710 (17.7%) | 357 (6.6%) | 398,751 (68.8%) | 87,620 (67.9%) | 489,439 (67.1%) |

| 1967 | 2 | 2,165 (7.5%) | 56 (2.1%) | 259,951 (69.2%) | 37,533 (43.9%) | 299,707 (60.8%) |

| 1968 | 1 | 1,550 (1.6%) | 106 (2.2%) | 191,691 (32.7%) | 20,283 (27.0%) | 213,631 (28.1%) |

| 1969 | 0 | 92 (0.1%) | 11 (1.8%) | 51,533 (25.5%) | 5,400 (8.8%) | 57,036 (14.7%) |

| 1970 | 5 | 4,177 (18.7%) | 243 (5.0%) | 302,879 (52.7%) | 118,746 (52.9%) | 426,050 (51.6%) |

| 1971 | 11 | 1,630 (7.3%) | 174 (3.8%) | 310,710 (79.1%) | 116,995 (78.7%) | 431,520 (75.9%) |

| 1972 | 7 | 26,423 (45.6%) | 17 (0.8%) | 1,005 (3.5%) | 43,490 (57.6%) | 70,942 (43.1%) |

| 1973 | 1 | 5,064 (17.3%) | 30 (1.4%) | 197,259 (64.2%) | 76,341 (66.1%) | 278,695 (61.3%) |

| 1974 | 1 | 399 (1.5%) | 28 (0.4%) | 1,678 (3.3%) | 11,931 (62.1%) | 14,037 (13.5%) |

| 1975 | 0 | 720 (2.6%) | 7 (0.1%) | 160,291 (15.1%) | 11,350 (52.4%) | 172,368 (15.4%) |

| 1976 | 7 | 18,886 (32.5%) | 0 (0%) | 93 (0.1%) | 412 (0.8%) | 19,398 (7.8%) |

| 1977 | 34 | 33,733 (33.7%) | 1,528 (53.2%) | 1,127,800 (87.3%) | 70,167 (48.1%) | 1,233,262 (80.0%) |

| 1978 | 236 | 10,695 (6.8%) | 45 (0.7%) | 70,080 (19.9%) | 19,224 (26.1%) | 100,280 (17.0%) |

| 1979 | 30 | 25,297 (39.3%) | 150 (1.2%) | 1,945,521 (65.0%) | 180,558 (82.6%) | 2,151,556 (65.4%) |

| 1980 | 12 | 22,514 (32.4%) | 16 (0.1%) | 154,041 (17.3%) | 32,246 (43.9%) | 208,827 (20.0%) |

| 1981 | 61 | 18,133 (16.4%) | 485 (4.5%) | 1,714,115 (52.3%) | 238,393 (70.9%) | 1,971,187 (52.7%) |

| 1982 | 129 | 66,781 (50.9%) | 92 (0.2%) | 67,523 (12.2%) | 63,075 (31.8%) | 197,600 (21.3%) |

| 1983 | 14 | 16,835 (9.0%) | 54 (0.5%) | 199,794 (21.5%) | 27,203 (14.1%) | 243,900 (18.5%) |

| 1984 | 3 | 29,276 (10.9%) | 41 (0.3%) | 89,085 (12.7%) | 3,204 (3.5%) | 121,609 (11.3%) |

| 1985 | 19 | 91,957 (33.0%) | 3,210 (31.1%) | 618,222 (50.3%) | 11,844 (38.7%) | 725,252 (46.8%) |

| 1986 | 6 | 48,472 (20.6%) | 5,052 (26.8%) | 401,755 (28.5%) | 11,701 (14.1%) | 466,986 (26.8%) |

| 1987 | 14 | 31,845 (12.8%) | 2,481 (17.3%) | 23,890 (11.9%) | 28,663 (18.3%) | 86,893 (14.0%) |

| 1988 | 5 | 9,501 (3.0%) | 2 (*) | 6,094 (0.7%) | 71,202 (22.1%) | 86,804 (5.5%) |

| 1989 | 1 | 10,286 (6.3%) | 72 (0.6%) | 52,677 (4.1%) | 43 (0.4%) | 63,079 (4.2%) |

| 1990 | 2 | 17,404 (8.5%) | 74 (0.8%) | 191,320 (49.9%) | 614 (8.8%) | 209,414 (34.6%) |

| 1991 | 2 | 6,408 (2.0%) | 12 (0.1%) | 359,664 (43.4%) | 14,337 (59.2%) | 380,423 (31.9%) |

| 1992 | 0 | 572 (0.3%) | 1 (*) | 146 (*) | 181 (0.8%) | 900 (0.1%) |

| 1993 | 2 | 4,613 (2.0%) | 119 (0.9%) | 159,159 (18.4%) | 970 (22.2%) | 164,863 (14.7%) |

| 1994 | 0 | 5,930 (5.1%) | 993 (6.8%) | 13,200 (0.8%) | 32 (0.6%) | 20,155 (1.1%) |

| 1995 | 12 | 17,642 (6.6%) | 1,272 (7.2%) | 192,098 (6.7%) | 474 (3.0%) | 211,498 (6.7%) |

Table 9-3. Eastern District (of Cook Inlet) Salmon Harvest, 1954-1995

Figures given are number of fish, while percentages are those of the entire LOWER Cook Inlet catch. An asterisk (*) signifies a percentage less than 0.1%. The Eastern District extends from Bear Glacier (at the southwestern end of Resurrection Bay) east to Cape Fairfield (between Whidbey and Johnstone bays). Source: ADF&G, Cook Inlet Finfish Report, 1976-1977, Table 18; and ADF&G, Lower Cook Inlet Finfish, Annual Management Report, 1995, Appendix Table 9.

An asterisk (*) signifies a percentage less than 0.1%. In regards to king salmon, no attempt was made to compute percentages. A number sign (#) is used because the number of kings harvested is relatively small: the Lower Cook Inlet harvest has never exceeded 2,000 per year, and in most years is fewer than 500.

| Year | Kings(#) | Reds | Cohos | Pinks | Chums | Total |

| 1954 | 0 | 11,786 (29.7%) | 2,256 (14.9%) | 7,562 (2.8%) | 1,945 (0.7%) | 23,849 (4.0%) |

| 1955 | 4 | 5,049 (13.8%) | 6,160 (63.7%) | 55,994 (4.7%) | 3,147 (4.6%) | 70,354 (5.4%) |

| 1956 | 0 | 296 (0.8%) | 3,761 (40.2%) | 14,873 (7.2%) | 519 (0.6%) | 19,450 (5.7%) |

| 1957 | 120 | 169 (0.6%) | 119 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (*) | 428 (0.1%) |

| 1958 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 200 (*) | 0 (0%) | 200 (*) |

| 1959 | 58 | 5,477 (25.3%) | 8,954 (95.0%) | 125 (0.1%) | 14,612 (13.2%) | 29,226 (11.1%) |

| 1960 | 0 | 105 (0.4%) | 853 (31.7%) | 8,720 (1.4%) | 467 (0.4%) | 10,415 (1.4%) |

| 1961 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1962 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 3,728 (48.2%) | 49 (*) | 10 (*) | 3,787 (0.2%) |

| 1963 | 1 | 1 (*) | 2,250 (33.4%) | 11 (*) | 0 (0%) | 2,263 (0.6%) |

| 1964 | 0 | 22 (0.1%) | 22 (0.2%) | 813 (0.1%) | 12 (*) | 869 (0.1%) |

| 1965 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1966 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1967 | 0 | 348 (1.2%) | 203 (7.4%) | 3,097 (0.8%) | 275 (0.3%) | 3,923 (0.8%) |

| 1968 | 2 | 74,484 (78.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 41,464 (7.1%) | 872 (1.2%) | 116,827 (15.4%) |

| 1969 | 3 | 99,403 (80.9%) | 6 (1.0%) | 1 (*) | 10 (*) | 99,423 (25.7%) |

| 1970 | 11 | 1,767 (7.9%) | 692 (14.2%) | 40,226 (7.0%) | 633 (0.3%) | 43,329 (5.2%) |

| 1971 | 21 | 2,198 (9.9%) | 1,115 (24.4%) | 1 (*) | 423 (0.3%) | 3,758 (0.7%) |

| 1972 | 12 | 82 (0.1%) | 903 (40.4%) | 18,190 (63.5%) | 743 (1.0%) | 19,930 (12.1%) |

| 1973 | 5 | 0 (0%) | 801 (38.1%) | 2 (*) | 0 (0%) | 808 (0.2%) |

| 1974 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 517 (7.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 517 (0.5%) |

| 1975 | 1 | 0 (0%) | 124 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 125 (*) |

| 1976 | 0 | 5 (*) | 200 (6.2%) | 35,423 (26.0%) | 45 (0.1%) | 35,673 (14.3%) |

| 1977 | 0 | 5,776 (5.8%) | 360 (12.5%) | 1,349 (0.1%) | 3,229 (2.2%) | 10,714 (7.0%) |

| 1978 | 0 | 2 (*) | 582 (8.9%) | 29,738 (8.4%) | 100 (1.4%) | 30,422 (5.1%) |

| 1979 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 296 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 296 (*) |

| 1980 | 0 | 122 (0.2%) | 426 (2.9%) | 155,779 (17.5%) | 720 (1.0%) | 157,047 (15.0%) |

| 1981 | 0 | 9,270 (8.4%) | 470 (4.4%) | 44,989 (1.4%) | 3,279 (1.0%) | 58,008 (1.6%) |

| 1982 | 0 | 3,092 (2.4%) | 950 (2.0%) | 143,639 (26.0%) | 7,698 (3.9%) | 155,379 (16.7%) |

| 1983 | 0 | 25,932 (13.8%) | 594 (5.3%) | 36,154 (3.9%) | 7,934 (4.1%) | 70,614 (5.4%) |

| 1984 | 47 | 54,420 (20.2%) | 536 (3.2%) | 136,797 (19.5%) | 10,535 (11.4%) | 202,335 (18.7%) |

| 1985 | 11 | 24,338 (8.7%) | 835 (8.1%) | 92,403 (7.5%) | 5,144 (16.8%) | 122,731 (7.9%) |

| 1986 | 0 | 3,055 (1.3%) | 770 (4.1%) | 40,243 (2.9%) | 3,757 (4.5%) | 47,825 (2.7%) |

| 1987 | 0 | 3,687 (1.5%) | 1,631 (11.4%) | 14,333 (7.1%) | 14,913 (9.5%) | 34,564 (5.5%) |

| 1988 | 1 | 20,253 (6.3%) | 486 (6.1%) | 1,740 (0.2%) | 24,668 (7.7%) | 47,148 (3.0%) |

| 1989 | 0 | 8,538 (5.2%) | 5,346 (44.2%) | 92 (*) | 312 (2.8%) | 14,288 (1.0%) |

| 1990 | 0 | 7,682 (3.8%) | 7,645 (82.2%) | 11,815 (3.1%) | 307 (4.4%) | 27,449 (4.5%) |

| 1991 | 1 | 4,703 (1.5%) | 7,283 (38.2%) | 167,250 (20.2%) | 80 (0.3%) | 179,317 (15.1%) |

| 1992 | 0 | 432 (0.2%) | 3,136 (53.1%) | 60,007 (12.5%) | 86 (0.4%) | 63,361 (9.2%) |

| 1993 | 0 | 1,824 (0.8%) | 8,924 (66.2%) | 10,616 (1.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | 21,373 (1.9%) |

| 1994 | 1 | 9,661 (8.3%) | 10,410 (70.9%) | 44,987 (2.7%) | 2,792 (51.1%) | 67,851 (3.8%) |

| 1995 | 0 | 46,556 (17.5%) | 5,192 (29.3%) | 12,000 (0.4%) | 330 (2.1%) | 64,078 (2.0%) |

The Onset of Regulation, 1955-1959

The Fish and Wildlife Service continued to ignore the park coastline through the 1954 season. Most of the fish harvested in the area, as before, were probably pink salmon that were caught near Nuka Island. In 1955, however, the agency instituted active management when it dispatched its first enforcement specialist to Nuka Island. Fishery aid F. Douglas Swanson was assigned to Nuka Bay for six days in mid-August. One of 273 agency enforcement personnel who worked Alaskan streams that summer, Swanson performed the typical duties that his predecessors had been undertaking since the 1920s. Those duties included enforcing closure regulations (particularly around stream mouths) and conducting spawning-ground observations. As part of his work, Swanson was the first governmental representative to learn of the existence of the Delight and Desire Lake sockeye run. John Skerry, the Fish and Wildlife Service's agent for Cook Inlet, concluded that because the run was unregulated, local fishers were therefore abusing the resource. Those fishers, moreover, had no interest in helping government agents. Skerry noted that "there is still a great deal to be learned of the various fish runs in [park waters]. Much of this has to be uncovered by personal observation due to the unco-operative attitude taken by the Seward fishermen." [51]

By 1956, the park coastline was becoming an increasingly popular fishing venue. Nuka Bay was now home to boats owned by Port Graham canneries; the Libby, McNeill and Libby company, which had a cannery on Kodiak Island; and one or more of the Seattle-based processing ships. These fishing boats, in turn, were supported by tenders that waited nearby. Aialik Bay, on the other hand, was fished primarily by Seward-based boats. During this period the Resurrection Bay harvests, which had been anemic since the 1930s, fell to the point that Seward's only cannery closed after the 1955 season. Despite the lack of a nearby cannery, Seward fishers continued to harvest the small if valuable Aialik Bay sockeye run. [52]

As a result of the stepped-up activity, federal fisheries personnel in 1956 increased their presence in park waters and moved to ensure the protection of the sockeye run that had been revealed to them the previous year. William Miller, who had been working as a Fish and Wildlife Service stream guard since 1953, was stationed at the mouth of Delight Creek from mid-June to late July; he then moved to Nuka Island, where he stayed until mid-August. He also served a stint at the head of Beauty Bay in Nuka Bay's West Arm. Another stream guard dispatched to the area that summer was John Frye, who arrived at the mouth of Delight Creek before Miller left. A Fish and Wildlife Service floatplane, which patrolled the Outer District for the first time, augmented Miller and Frye's observations and enforcement capabilities. [53] During the same general period–probably in the mid-1950s, according to one old-time fisherman–the Fish and Wildlife Service stationed a stream guard in a tent at the edge of Pederson Lagoon, in Aialik Bay. Here, as in Nuka Bay, the guard remained until fishermen left the area. [54]

|

| Markers such as this one were posted near various Kenai Fjords stream mouths beginning in the mid-1950s. Alaska Geographic 10:3 (1983), 9. |

Miller's experiences as a stream guard, like Swanson's, were more or less typical of those who served in that capacity elsewhere in Alaska during territorial days. It was Miller's job to monitor activity surrounding the buoys that had been placed 500 yards from the mouth of salmon streams. Because pink and chum salmon commonly school at stream mouths, regulations prohibited fishing boats from passing beyond the buoys, which were marked with plywood, three-foot-square stream markers. Fishing boats, however, often lurked just beyond the markers, particularly at high tide. In an intricate game of cat-and-mouse, many boats tried–in various, devious ways–to fish inside the buoy perimeter without being detected. Miller, equipped with a small, motorized skiff, was asked to establish a presence and prevent fisheries violations; during his stay on Nuka Island, he was responsible for monitoring the fishing activities at several island streams simultaneously. Miller led a rugged life that summer; on Nuka Island, he stayed in one of Pete Sather's abandoned fox shacks, while at Delight Creek, he camped in a tent. [55]

Miller and the other stream guards recognized that the Nuka Bay pink runs for 1956 were "not as great" as in 1955, even though the even-year pink fishery was traditionally dominant. Worried that the pink population could not be sustained under the current system, fisheries agent John Skerry recommended that the season end on August 18. The suggestion was quickly implemented. The stream guards also made a number of baseline stream surveys. Streams surveyed for the first time included Nuka Island Creek, Home Cove, South Creek, Mike Bay, and Duck Bay–all of which were located on Nuka Island–along with Desire and Delight creeks, which flowed into McCarty Fjord. Stream mouths marked that summer were located at Delight and Desire creeks, Home Cove, the unnamed cove south of Home Cove, and Nuka Bay Creek. [56]

From 1957 to 1959, the park fishery continued to be managed in much the same way as in 1956. At least one fisheries enforcement person was dispatched to Nuka Bay each summer; stream guard work continued to take place at Delight Creek and several Nuka Island locations. [57] On a more occasional basis, personnel tallied escapement levels, surveyed streams, and measured stream temperatures. One summer, the agency patrolled the area with its Grumman Goose; a year later the agency's patrol vessel, the Kittiwake, checked Nuka Bay's closure markers. [58]

Specific changes during this period were few. The various stream guards welcomed one of those changes; in 1957, the shelters at both Nuka Island Creek and Delight Creek were upgraded from tents to an 8' x 10' tent frame, with walls and roof made of corrugated aluminum. A second change involved enforcement methods. The existing system of stream mouth protection was apparently less than effective, so agency managers adopted a stakeout system in which the stream guards hid in the undergrowth and watched for stream robbers. This practice was more cost-effective than the previous system had been and it resulted in more fisheries violations, but local fishers became angrier than ever at federal fishing policies. [59]

Commercial Salmon Fishing Since Statehood

Statehood and Its Ramifications, 1960-1963

The relative continuity of fisheries management along the Kenai Peninsula's outer coast, and fisheries management throughout Alaska, was abruptly changed by statehood. A statehood bill passed Congress in June 1958, but Alaska did not enter the Union until January 1959, and the new state did not assume responsibility for fisheries management until 1960. Therefore, fisheries management for the first year after statehood continued much as it had during territorial days.

When the Alaska Department of Fish and Game assumed control of the new state's fisheries, the health of Alaska's salmon stocks had been declining for years. A major reason for the declining stocks was the strong bond between the canneries and the Fish and Wildlife Service, both being based outside Alaska. Jim Rearden, a longtime Fish and Game biologist, has remarked that "all the agency cared about was the canneries," and the canneries had a near-total influence over territorial fishing regulations. Independent fishermen, and Alaskans in general, strongly resented their own lack of influence over fisheries regulations. One manifestation of that resentment was that some Alaska fishers robbed fish along creeks and at stream mouths. [60] As noted above, many Alaskans equated federal fisheries management with the fish trap. While the number of fish traps slowly declined during the years that preceded statehood, the widely hated traps were not eliminated until Congress passed the statehood bill.

Another reason that Alaska's salmon stocks were in relatively poor shape was because of the nature of fisheries regulation. Jim Rearden has noted that

under Federal control, the regulations were generally adopted six months or more in advance of the fishing season and they were virtually inflexible; any change had to be published in the Federal Register before it became effective. Once a regulation was in place, there was little chance of modifying it, regardless of its effect on fishermen or on the salmon.

The transfer to state management, however, made the adoption of fisheries rules far easier; rule changes, via "emergency orders," could be made by field announcement and implemented within hours. [61] Those regulations, moreover, were generated by an Alaskan, not Federal, bureaucracy. Fisheries policy was set by a statewide board appointed by Alaskans and subject to a public hearing process. Because of the changes in fisheries management that followed statehood, local antagonism against fisheries regulations lessened. The resentment did not, however, evaporate. Some fishers continued to fish out of season, at stream mouths, and in other ways contrary to the newly constituted regulations.

Other changes that followed statehood were easily visible on the fishing grounds. The placing of stream guards continued after statehood, but the unpopular stakeout program was eliminated. The number of Alaska stream guards, moreover, shrank considerably. In park waters, stream guards continued at Home Cove on Nuka Island and in the Delight-Desire Creek area, [62] but apparently no guards were deployed to Aialik Bay after statehood. The guards' survey duties, to an increasing degree, were taken over by a Fish and Game biologist who periodically flew over the area–either from Port Dick to Resurrection Bay, or from the head of Kachemak Bay to Nuka Bay and on to Resurrection Bay–in a Super Cub. (The small, maneuverable Cub had a distinct advantage over the Grumman Goose used by federal fisheries managers. The Cub could fly as slowly as 65 or 70 miles per hour without stalling–slow enough that biologists could count the spawners from the air–while the Goose's stall speed was 140 or 150 miles per hour.) Stream guards returned to the area in the summer of 1961, and perhaps again in 1962; they then left the Outer Coast, never to return. [63]

By the time the State of Alaska began managing the park area fishery, the southern coast's salmon runs had become sufficiently well known–and its harvest statistics had become sufficiently reliable–that its contribution to the overall Cook Inlet regional fishery could be assessed (see Table 9-4). Fish and Game personnel recognized that Nuka Bay (i.e., the stretch of coastline between Gore Point and the Pye Islands) had a fairly strong run of pink, chum and sockeye salmon; the Aialik Bay area had a sizable sockeye run; and Resurrection Bay had distinctive pink, chum, and sockeye runs. For those reasons, historical statistics are provided in the following paragraphs for three of the five salmon species. (Relatively small numbers of coho and king salmon are harvested in park waters, or elsewhere in the Outer District, so no specific statistics are provided for those species.)

Table 9-4. Salmon Harvest, by Number of Fish (in thousands) and Percentage of Total Harvest for Selected Periods, 1954-1994

| Year | chinook salmon (410) (#/pounds) |

sockeye salmon (420) (#/pounds) |

coho salmon (430) (#/pounds) |

pink salmon (440) (#/pounds) |

chum salmon (450) (#/pounds) |

salmon total (#/pounds) |

| Outer District Figures: | ||||||

| 1954-59 | 0 — 0.0% | 23.6 — 1.1% | 1.1 — 0.1% | 1,640.4 — 76.6% | 477.2 — 22.3% | 2,142.4 |

| 1960-65 | 0 — 0.0% | 25.9 — 0.7% | 3.7 — 0.1% | 2,936.8 — 81.1% | 654.7 — 18.1% | 3,621.2 |

Statistical Area 232 Figures: | ||||||

| Year | chinook salmon (410) (#/pounds) |

sockeye salmon (420) (#/pounds) |

coho salmon (430) (#/pounds) |

pink salmon (440) (#/pounds) |

chum salmon (450) (#/pounds) |

salmon total (#/pounds) |

| 1968-69 | 0 — 0.0% | 0.1 — 0.2% | 0 — 0.0% | 64.6 — 91.9% | 5.5 — 7.9% | 70.3 |

| 1970-74 | 0 — 0.0% | 37.6 — 13.3% | 0 — 0.0% | 190.9 — 67.6% | 53.8 — 19.1% | 282.4 |

| 1975-79 | 0.3 — 0.0% | 89.4 — 2.5% | 1.6 — 0.0% | 3,179.2 — 89.7% | 274.0 — 7.7% | 3,544.7 |

| 1980-84 | 0.1 — 0.0% | 153.5 — 5.6% | 0.5 — 0.0% | 2,224.5 — 81.1% | 364.0 — 13.3% | 2,743.1 |

| 1985-89 | 0 — 0.0% | 192.1 — 13.4% | 10.6 — 0.7% | 1,102.7 — 77.2% | 123.4 — 8.6% | 1,429.0 |

| 1990-94 | 0 — 0.0% | 34.3 — 4.4% | 1.0 — 0.1% | 723.5 — 93.3% | 15.9 — 2.1% | 775.1 |

Source: Tables 9-2 and 9-8.

Statistics collected during the 1960-1963 period show that in regard to pink salmon (see Table 9-5), Nuka Bay had fairly strong harvests during even-numbered years. These harvests numbered more than 25,000 fish per year, and comprised between 4% and 6% of the total Lower Cook Inlet harvest. Its odd-year harvests, however, were so small that they comprised less than 1% of the Lower Cook Inlet harvest. During all four of these years, the Resurrection Bay harvest was far less than that in Nuka Bay; in 1961 and 1963, in fact, the harvest was nonexistent. But the Port Dick harvest–just west of Nuka Bay–was far greater than in any park area.

Table 9-5. Commercial Pink Salmon Harvest for Selected Lower Cook Inlet Bays, 1959-1995

Figures given are in numbers of fish (in thousands), while percentages are those of the entire Lower Cook Inlet catch. (Lower Cook Inlet includes all Kenai Peninsula Streams between Anchor Point and Cape Fairfield, plus all west-side waters between Cape Douglas and the Iniskin Peninsula.) Source: ADF&G, 1995 Lower Cook Inlet Annual Finfish Management Report, Appendix Tables 19 and 20. T = trace (i.e., fewer than 50 fish), * = percentage less than 0.1%.

| Year | Port Dick Bay | Nuka Bay | Resurrection Bay | Total, Lower Cook Inlet |

| 1959 | 28.2 (22.6%) | 33.3 (26.7%) | 8.4 (6.7%) | 124.7 |

| 1960 | 257.4 (42.1%) | 26.6 (4.3%) | 5.8 (0.9%) | 611.6 |

| 1961 | 92.9 (30.6%) | 2.0 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 303.4 |

| 1962 | 1,118.3 (49.7%) | 129.8 (5.8%) | 0.1 (*) | 2,248.3 |

| 1963 | 19.0 (9.3%) | 0.3 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 203.6 |

| 1964 | 526.3 (49.9%) | 23.8 (2.3%) | 0.3 (*) | 1,055.4 |

| 1965 | 15.3 (13.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 115.6 |

| 1966 | 296.8 (51.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 579.2 |

| 1967 | 259.9 (69.2%) | 0.1 (*) | 1.2 (0.3%) | 375.5 |

| 1968 | 55.0 (9.4%) | 90.2 (15.4%) | 37.4 (6.4%) | 585.4 |

| 1969 | 51.5 (25.4%) | 0 (*) | 0 (0%) | 202.4 |

| 1970 | 193.8 (33.7%) | 48.4 (8.4%) | 40.2 (7.0%) | 574.3 |

| 1971 | 94.6 (24.1%) | 119.7 (30.5%) | 0 (0%) | 392.9 |

| 1972 | 0 (0%) | 0.3 (1.0%) | 18.2 (63.4%) | 28.7 |

| 1973 | 96.6 (31.4%) | 8.1 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | 307.4 |

| 1974 | 0.6 (1.2%) | 0.7 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 50.6 |

| 1975 | 90.3 (8.5%) | 35.4 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1,063.4 |

| 1976 | 0 (0%) | 0.1 (0.1%) | 35.4 (26.0%) | 136.4 |

| 1977 | 881.7 (68.1%) | 56.3 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1,293.9 |

| 1978 | 63.6 (18.0%) | 6.3 (1.8%) | 29.7 (8.4%) | 352.6 |

| 1979 | 964.8 (32.3%) | 121.7 (4.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2,990.9 |

| 1980 | 133.3 (15.0%) | 12.8 (1.4%) | 155.8 (17.4%) | 889.7 |

| 1981 | 1,140.9 (35.7%) | 395.1 (12.3%) | 32.6 (1.0%) | 3,199.2 |

| 1982 | 44.0 (8.0%) | 8.7 (1.6%) | 137.4 (24.9%) | 551.6 |

| 1983 | 140.0 (15.1%) | 55.0 (5.9%) | 27.1 (2.9%) | 927.6 |

| 1984 | 84.6 (12.1%) | 4.4 (0.6%) | 122.3 (17.5%) | 700.6 |

| 1985 | 455.6 (37.0%) | 150.8 (12.3%) | 74.6 (6.1%) | 1,229.7 |

| 1986 | 304.0 (21.6%) | 97.8 (6.9%) | 36.5 (2.6%) | 1,408.3 |

| 1987 | 3.0 (1.5%) | 20.9 (10.4%) | 11.8 (5.9%) | 201.4 |

| 1988 | 5.9 (0.6%) | 0.2 (*) | 0.5 (0.1%) | 921.3 |

| 1989 | 0 (0%) | 43.0 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1,296.9 |

| 1990 | 169.1 (44.1%) | 0.2 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 383.7 |

| 1991 | 289.7 (35.0%) | 10.6 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 828.7 |

| 1992 | 0.1 (*) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 479.8 |

| 1993 | 26.6 (3.1%) | 13.8 (1.6%) | 0.7 (0.1%) | 866.8 |

| 1994 | 1.6 (0.1%) | 11.6 (0.7%) | T (*) | 1,647.9 |

| 1995 | 0 (0%) | 21.4 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2,848.5 |

Regarding chum salmon (see Table 9-6), the Nuka Bay harvest was fairly strong in both 1960 and 1961; the bay yielded more than 3% of the Lower Cook Inlet harvest in both years. During the following two years, however, the chum runs there slid into insignificance. As with pink salmon, the Nuka Bay harvests were consistently greater than in Resurrection Bay, which had almost no harvest activity, while the Port Dick harvest was many times greater than in Nuka Bay.

Table 9-6. Commercial Chum Salmon Harvest for Selected Lower Cook Inlet Bays, 1959-1995

Figures given are in numbers of fish (in thousands), while percentages are those of the entire Lower Cook Inlet catch. (Lower Cook Inlet includes all Kenai Peninsula Streams between Anchor Point and Cape Fairfield, plus all west-side waters between Cape Douglas and the Iniskin Peninsula.) Source: ADF&G, 1995 Lower Cook Inlet Annual Finfish Management Report, Appendix Table 22. T = trace (i.e., fewer than 50 fish), * - less than 0.1%.

| Year | Port Dick Bay | Nuka Bay | Resurrection Bay | Total, Lower Cook Inlet |

| 1959 | 42.4 (38.3%) | 1.7 (1.5%) | 0.1 (0.1%) | 110.8 |

| 1960 | 53.9 (46.4%) | 8.4 (7.2%) | 0.5 (0.4%) | 116.1 |

| 1961 | 36.8 (66.2%) | 1.7 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 55.6 |

| 1962 | 112.0 (62.5%) | 0.5 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 179.3 |

| 1963 | 110.8 (80.0%) | 1.5 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 138.5 |

| 1964 | 227.4 (70.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 323.3 |

| 1965 | 14.2 (50.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 28.1 |

| 1966 | 60.9 (47.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 129.1 |

| 1967 | 36.0 (42.2%) | 1.5 (1.8%) | 0.1 (0.1%) | 85.4 |

| 1968 | 10.9 (14.5%) | 6.9 (9.2%) | 0.7 (0.9%) | 75.1 |

| 1969 | 5.4 (8.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 61.2 |

| 1970 | 21.8 (9.7%) | 5.9 (2.6%) | 0.4 (0.2%) | 224.2 |

| 1971 | 0.7 (0.5%) | 0.1 (0.1%) | 0.4 (0.3%) | 148.6 |

| 1972 | 0 (0%) | 2.3 (3.0%) | 0.7 (0.9%) | 75.5 |

| 1973 | 33.4 (28.9%) | 40.8 (35.3%) | 0 (0%) | 115.5 |

| 1974 | 8.1 (42.2%) | 3.9 (20.3%) | 0 (0%) | 19.2 |

| 1975 | 6.8 (31.5%) | 3.6 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | 21.6 |

| 1976 | 0 (0%) | 0.4 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 50.8 |

| 1977 | 25.6 (17.6%) | 17.4 (11.9%) | 0 (0%) | 145.8 |

| 1978 | 10.3 (14.0%) | 0.4 (0.6%) | 0.1 (0.1%) | 73.5 |

| 1979 | 79.0 (36.2%) | 14.7 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 218.5 |

| 1980 | 19.0 (25.9%) | 7.8 (10.6%) | 0.7 (1.0%) | 73.5 |

| 1981 | 85.8 (25.5%) | 3.8 (1.1%) | 2.4 (0.7%) | 336.1 |

| 1982 | 30.3 (15.3%) | 0.9 (0.4%) | 7.7 (3.9%) | 198.0 |

| 1983 | 18.0 (9.4%) | 0.8 (0.4%) | 6.9 (3.6%) | 192.3 |

| 1984 | 1.9 (2.1%) | 0.2 (0.2%) | 3.0 (3.2%) | 92.5 |

| 1985 | 9.6 (31.4%) | 0.8 (2.6%) | 3.0 (9.8%) | 30.6 |

| 1986 | 10.4 (12.6%) | 1.3 (1.6%) | 3.5 (4.2%) | 82.7 |

| 1987 | 27.1 (17.3%) | 1.6 (1.0%) | 13.9 (8.9%) | 157.0 |

| 1988 | 64.4 (20.0%) | 6.8 (2.1%) | 23.9 (7.4%) | 321.9 |

| 1989 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 11.3 |

| 1990 | 0.5 (7.1%) | T (*) | 0 (0%) | 7.0 |

| 1991 | 13.7 (56.6%) | T (*) | 0 (0%) | 24.2 |

| 1992 | 0.2 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 22.2 |

| 1993 | 0.7 (15.9%) | T (*) | 0 (0%) | 4.4 |

| 1994 | T (*) | T (*) | 2.5 (45.5%) | 5.5 |

| 1995 | 0 (0%) | 0.1 (0.6%) | 0.3 (1.9%) | 15.6 |

As to the sockeye run (see Table 9-7), the number of fish caught in both Aialik Bay and Nuka Bay was no larger, in general, than either the pink or chum harvest. But because the Lower Cook Inlet is not normally considered a significant sockeye region, these two bays often contributed more than 10% of the region's total harvest. More important, sockeye salmon's relatively high value (more than twice the price, on a per-pound basis, than either pinks or chums) ensured that both fishers and agency officials paid especial attention to the health of those runs. The Nuka Bay and Aialik Bay runs were far greater than were those in adjacent districts along Kenai Peninsula's southern coast.

Table 9-7. Commercial Sockeye Salmon Harvest for Selected Lower Cook Inlet Bays, 1959-1995

Figures given are in numbers of fish (in thousands), while percentages are those of the entire Lower Cook Inlet catch. (Lower Cook Inlet includes all Kenai Peninsula Streams between Anchor Point and Cape Fairfield, plus all west-side waters between Cape Douglas and the Iniskin Peninsula.) Source: ADF&G, 1995 Lower Cook Inlet Annual Finfish Management Report, Appendix Table 14. T = trace (i.e., fewer than 50 fish), * - less than 0.1%.

| Year | Port Dick Bay | Nuka Bay | Resurrection Bay | Total, Lower Cook Inlet |

| 1959 | 1.3 (6.0%) | 8.3 (38.4%) | 0 (0%) | 21.6 |

| 1960 | 0.2 (0.8%) | 6.7 (27.1%) | 0.1 (0.4%) | 24.7 |

| 1961 | 4.3 (18.9%) | 8.2 (36.0%) | 0 (0%) | 22.8 |

| 1962 | 2.6 (10.3%) | 5.1 (20.2%) | 0 (0%) | 25.3 |

| 1963 | 0.5 (3.3%) | 0.5 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 15.1 |

| 1964 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 20.7 |

| 1965 | 0 (0%) | 2.0 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 14.0 |

| 1966 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 15.3 |

| 1967 | 0 (0%) | 2.2 (7.6%) | 0 (0%) | 29.0 |

| 1968 | 0 (0%) | 1.5 (1.6%) | 74.5 (78.3%) | 95.2 |

| 1969 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 99.4 (80.9%) | 122.8 |

| 1970 | 3.1 (13.9%) | 1.0 (4.5%) | 1.7 (7.6%) | 22.3 |

| 1971 | 0 (0%) | 1.6 (7.2%) | 2.2 (9.9%) | 22.2 |

| 1972 | 0.3 (0.5%) | 26.1 (45.1%) | 0.1 (0.2%) | 57.9 |

| 1973 | 3.1 (10.6%) | 1.5 (5.1%) | 0 (0%) | 29.2 |

| 1974 | 0.2 (0.7%) | 0.2 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 27.4 |

| 1975 | 0.6 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 28.1 |

| 1976 | 0 (0%) | 18.9 (32.5%) | 0 (0%) | 58.2 |

| 1977 | 5.8 (5.8%) | 32.5 (32.5%) | 0 (0%) | 100.1 |

| 1978 | 0 (0%) | 10.7 (6.8%) | 0 (0%) | 156.4 |

| 1979 | 0 (0%) | 24.4 (37.9%) | 0 (0%) | 64.4 |

| 1980 | 0.1 (0.1%) | 21.5 (31.0%) | 0 (0%) | 69.4 |

| 1981 | 8.7 (7.9%) | 17.2 (15.6%) | 0.6 (0.6%) | 110.3 |

| 1982 | 3.0 (2.2%) | 66.3 (50.5%) | 0 (0%) | 131.3 |

| 1983 | 25.9 (13.8%) | 16.8 (9.0%) | 0 (0%) | 187.6 |

| 1984 | 50.8 (18.9%) | 29.2 (10.9%) | 3.4 (1.3%) | 269.0 |

| 1985 | 24.1 (8.6%) | 91.8 (32.9%) | 0.3 (0.1%) | 278.7 |

| 1986 | 3.0 (1.3%) | 48.4 (20.6%) | 0 (0%) | 234.9 |

| 1987 | 3.5 (1.4%) | 31.8 (12.8%) | 0.2 (0.1%) | 248.8 |

| 1988 | 20.2 (6.3%) | 9.5 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 319.0 |

| 1989 | 8.5 (5.2%) | 10.3 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | 163.3 |

| 1990 | 7.7 (3.8%) | 5.7 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 203.9 |

| 1991 | 4.7 (1.5%) | 1.8 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 317.9 |

| 1992 | 0.4 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 176.6 |

| 1993 | 0.2 (0.1%) | 3.5 (1.5%) | 1.7 (0.7%) | 233.8 |

| 1994 | 0.6 (0.5%) | 5.9 (5.1%) | 9.0 (7.8%) | 115.4 |

| 1995 | 2.0 (0.8%) | 17.6 (6.6%) | 44.6 (16.8%) | 265.4 |

The Good Friday Earthquake and Its Aftermath

At 5:36 p.m. on March 27, 1964, a massive earthquake struck southcentral Alaska. The earthquake measured between 8.2 and 8.4 on the Richter scale; its epicenter was near the north end of College Fjord, approximately 50 miles west of Valdez. The earthquake and the resulting aftershocks, tsumanis and submarine landslides killed 115 people and caused an estimated $380 to $500 million in property damage. [64]

The earthquake devastated Seward, where 11 deaths were recorded and property damage totaled more than $14.6 million. The quake hit Seward, and the park coastline, particularly hard because although the epicenter was more than 100 miles to the northeast, the earthquake's main fault line (and thus its "area of epicenter") paralleled the coast and included most of the park. The park was thus subject to many of the quake's most devastating effects. The earthquake in the park lasted from 2-1/2 to 5 minutes. [65]

One of the earthquake's most substantial impacts was its effect on land elevations. Some areas of southcentral Alaska, in effect, rose from the sea; one site on Montague Island (in Prince William Sound) rose 33 feet. The area within the park, however, was in a zone of subsidence. Maps published as a result of post-earthquake scientific studies show that the quake's "axis of maximum subsidence" went right through the park; it was a sinuous line that wound from the western end of Kenai Lake to the eastern edge of Nuka Island. Areas that were relatively distant from that axis subsided only slightly; the southern tip of Aialik Peninsula, for instance, sank only a foot. But Aialik Bay dropped 4.5 feet, both Two Arm Bay and Shelter Cove (the latter in Nuka Bay) subsided 5.4 feet, and both Beauty Bay (in Nuka Bay) and Chance Cove (just east of McArthur Pass) dropped 6.6 feet. Some areas astride the axis fell as much as 7.5 feet. Near the Sather residence, on the western side of Nuka Island, the water rose and covered part of the warehouse; the quake also destroyed the adjacent boat dock. [66]

The other major impact caused by the March 27 earthquake was a series of tsunamis (large waves) that hit the coast within one-half hour of the quake. The quake generated a large tsunami out in the Gulf of Alaska; the tsunami rose in height as it reached the coast due to the funneling effect of the various fjords. In Resurrection Bay, the tsunami was an estimated 30 to 40 feet high as it neared the bay's northern end; a 30-foot wave slammed into Thumb Cove, on the bay's eastern side, and it was at least that high when it reached Seward. Waves entering Aialik Bay were far higher. [67] Gene Rusnak, a USGS employee, observed that a wave between 90 and 100 feet high hit on either side of Aialik Bay's terminus; spruce trees up to 18 inches in diameter were snapped throughout the area where the wave hit. These waves were particularly devastating because the quake generated submarine landslides that exacerbated the tsunami's effects. Huge waves also hit Port Dick; other bays between there and Aialik Bay were also probably affected, but specific details are lacking. [68]

The lowering of the landmass, in combination with the effects of the tsunami, had devastating consequences on the park's fish population. Both factors, particularly the former, inundated the gravel at stream mouths that was key to pink and chum salmon spawning. (The earthquake had varying impacts on sockeye populations, where spawning took place in upstream lakes; the Aialik Bay population was wiped out for years afterward, probably because of the tsunami's effects, while at Delight and Desire creeks, the impacts were significant but not devastating.) [69] The salmon industry was also crippled because facilities were destroyed. The quake wrecked canneries in Seldovia and elsewhere in lower Cook Inlet. In Seward, four seafood processors were destroyed; of those, Halibut Producers' Co-operative was back on line a year later, but Seward Seafoods and the other processors never reopened. Many fishing boats were destroyed in both locations, and the quake resulted in the death of at least one Seward-area fisherman. [70]

Statistics for the remainder of the decade illustrate the extent of the earthquake's destruction. Nuka Bay pink salmon harvests for 1964 were low, although within a normal range; but for the next three years they were almost nonexistent. The only productive year for the remainder of the decade was 1968, when the Nuka Bay fishery constituted more than 15 percent of the total Lower Cook Inlet pink salmon harvest. Similar impacts were recorded in nearby Resurrection Bay. But in Port Dick, to the west, the quake had few if any impacts on the pink harvest.

Chum salmon harvests followed a similar pattern. In both Nuka Bay and Resurrection Bay, no chum harvest was recorded from 1964 through 1966, inclusively. Both bays recorded a fairly healthy harvest in 1968 but none in 1969. The Port Dick area, meanwhile, saw chum harvest tumble from more than 100,000 per year during the 1962-64 period to just 10,000 fish in 1968 and 5,000 in 1969.