|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 8:

IMPACTS OF MILITARY ACTIVITIES

The military has long been interested in the Kenai Peninsula's southern coastline. Resurrection Bay, one of many indentations along that coastline, has enormous strategic value; it remains ice-free all year long, and the topography north of the bay is sufficiently gentle that roads and rail lines beginning here have penetrated the interior. These routes, as noted in Chapter 5, have allowed the area to serve as a commercial entrepôt for much of southcentral and interior Alaska. Because of its strategic value, Resurrection Bay has been the military's primary focus. Certain aspects of military activity, however, have taken place in or near present-day parklands.

Early Plans and Activities

|

| Map 8-1. Historic Sites-Military Activity. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Russian authorities, through naval charts and occasional expeditions, knew of Resurrection Bay's strategic value by the mid-nineteenth century. During the first two decades after the U.S. government purchased Russian America, the bay's strategic value was largely overlooked. Beginning in the 1880s, however, the Lowell family's settlement and roadbuilding activities connected with Hope-Sunrise mining operations increased that value. As noted in Chapter 5, the U.S. military had the opportunity to see the area for themselves during the Klondike gold rush period; in May 1898, a three-man army expedition sailed to the head of Resurrection Bay and trekked north to Kenai Lake. Five years later, the town of Seward was founded and a railroad toward Alaska's interior was begun. From that point on, most of those interested in Alaska recognized that Seward and Resurrection Bay would be a primary access corridor into southcentral and interior Alaska. This fact was of considerable interest to both military and civilian authorities.

The military first signaled its interest in the Seward area in March 1907, shortly after Congress appropriated study funds for a suitable harbor along the "southern Alaska coast" for a navy yard and navy station. An army expedition, in 1898, had located a substantial coal deposit along the Chickaloon River, a branch of the Matanuska River near present-day Sutton; the Navy, recognizing that the Alaska Central was being built northward to make the coal deposit more accessible, was interested in constructing a coal transfer facility along the coast. But the Navy also knew of another potentially large deposit–the Bering River coal beds–so the study was intended to decide which field should be developed. [1]

During the summer of 1907, the Navy began to lean toward selecting a location near Seward, and in late September, a navy ship arrived to choose an appropriate site for a Naval Coaling Depot. By November, naval authorities had announced their intention to withdraw a 3,350-acre parcel along the west side of Resurrection Bay; it would be 2-1/2 miles from north to south and include both the Spruce Creek and Tonsina Creek drainage, and would go two miles west from the bay. The coaling depot would be sited at Lowell Point. President Roosevelt withdrew the parcel on February 21, 1908. [2]

Development of the parcel, however, had to wait until coal could be cheaply brought to the site and the Navy had demonstrated a need for it. Those conditions would not be fulfilled any time soon because President Roosevelt, in a widely disparaged move, withdrew Alaska's coal reserves from entry in November 1906. (Roosevelt issued his edict because, in his opinion, existing laws limiting coal-mine claims to 160 acres were unworkable and conducive to fraud.) Naval authorities were further stymied because the Alaska Central's end of track was more than a hundred miles away from the coalfields. [3]

Events on the federal level soon re-ignited interest in the Chickaloon River coal resources and Seward's role in the coal lands' development. On May 28, 1908, Congress passed the Alaska Coal Act, which permitted lands intended for coal developments to be consolidated in claims of up to 2,560 acres. Soon afterward, construction on the Alaska Central stopped, and as noted in Chapter 5, the transfer of the railroad's assets to the Alaska Northern did not result in additional track mileage. Construction remained at a standstill until 1912, when Congress authorized the construction of the Alaska Railroad. In 1914, Congress passed a coal-land leasing bill, which further stimulated Alaska coal development. The government, recognizing that the Chickaloon deposit would become accessible in the near future, extracted 800 tons of coal as a pilot project during the winter of 1913-14. It tested the coal and found it had good burning properties. That test stimulated further site development. The government made no secret of its intention to use Chickaloon coal to power U.S. Navy vessels. It needed to do so because the U.S., with its growing international stature, had many new navy ships docked in Pacific Coast ports, but it had few west-coast sources of cheap, plentiful coal. [4]

As a result of those actions, the military again became interested in the Seward area. By February 1916, local officials had been informed that Resurrection Bay "may be the location of a coaling station in the near future." Seven months later, President Wilson set aside Rugged Island as a military reservation, perhaps as a proposed coaling-station site. [6] Meanwhile, railroad construction (which included the rehabilitation of the old Alaska Central route) had begun in April 1915; it reached Anchorage in the fall of 1916, and by October 1917 the rails had been extended to the mine at Chickaloon. A coal train arrived there soon afterward, and on October 30, the first shipment from the government-owned mine arrived in Anchorage. [6]

Coal continued to be mined at Chickaloon for the next several years. Only a small amount, however, was mined each year; in 1919, for example, just 4,000 tons were extracted. The coal, moreover, was used locally, thus obviating any need for a Seward-area coaling station. The Navy, during this period, made no move to develop or use the mine. [7]

Beginning in 1919, the Navy decided to increase its involvement in the area. A Navy Commission report that year recommended that land be set aside at Seward "for a Navy pier and coal-handling plant," and in August, President Wilson issued an order setting aside acreage at the east end of Monroe Street "for the erection of wharves, coal storage yards and other Naval purposes." During the summer of 1920, Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels and other officials traveled to both Seward and Chickaloon to assess the situation for themselves. On the heels of that visit, the Navy decided to invest more than $1 million in the development of the Chickaloon coal deposit. During the next two years exploration activity was dramatically intensified, more than a hundred workers were brought to the area, a commodious townsite was constructed, and an imposing coal washing plant–begun in 1921 and completed in March 1922–was built several miles away. [8]

The washing facility had been completed for just two weeks when, on March 30, 1922, Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall abruptly announced that the Navy, on May 1, would close the mine and abandon the coal-washing plant. Navy officials did so because, after further tests, they found east coast coal superior to Alaska coal; because they knew that a large-scale Alaska coal source was available in case of an emergency; and because the discovery of vast new California oil fields portended the Navy's gradual transition from coal-powered to oil-powered ships. As a result of the Navy's decision, Seward never received large volumes of Chickaloon coal, and the military never constructed a Seward-area coaling station. [9]

During the summer of 1923, the hopes of Seward citizens were buoyed once again, when a survey ship visited the bay "with a view to the establishment of a navy base at some point in Alaska." The Navy, however, did not follow through on its proposal, either in the Seward area or anywhere else in the territory. By January 1925, Rugged Island was declared "useless for military purposes" and the former withdrawal was revoked. [10]

Although no facilities were constructed in conjunction with Seward area military reservations, the military was nevertheless active in Seward during this period. The government, which was constructing the railroad, had a large number of foreign nationals on the various construction crews. When the U.S. government entered World War I in April 1917, emotions rose and some of those foreigners were regarded as "enemy aliens." That same month, therefore, Seward's Spanish-American veterans' group organized an ad hoc committee for public safety and defense. By year's end, Seward's so-called Council of Defense was large and well organized, and in early 1918, its leaders requested that a military detachment be brought from nearby Fort Liscum (near Valdez) to patrol the city. The local citizens' group, which was later known as the Seward Home Guard, disbanded in March 1919. The military detachment, however, remained after the cessation of hostilities, and it was not until the summer of 1921 that the soldiers returned to Fort Liscum. A new detachment arrived in town the following summer; it probably remained until the railroad was completed in mid-1923, then left soon afterward. [11]

The military, during this period, also maintained a radio station on the Resurrection River flats north of Seward. In February 1916, the local chamber of commerce wrote the Navy Secretary and urged that a radio station would be a necessary adjunct to the proposed naval coaling station. Perhaps in response, personnel from the Naval Communication Service arrived in town that August to select an appropriate site. A 40-acre site north of town (near today's airport) was withdrawn the following April, and by December 1917 facilities had been constructed and the station was operating. The stationed remained until August 1923, when budget cuts forced its closure, but the Naval Radio Service reopened the facility in April 1924. The U.S. Army Signal Corps assumed control over the station in June 1926 and operated it until it was abandoned in 1930. [12]

World War II Activities in

Seward

During the 1930s, Japan became increasingly militaristic; in 1931 it invaded Manchuria, in 1934 it denounced the five-nation Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922, and in 1936 it allowed the treaty to lapse. War clouds grew, both in Europe and the Pacific, and on September 1, 1939, World War II began in Europe. In order to be prepared for war, Alaska's Congressional Delegate, Anthony Dimond, repeatedly urged Congress to fund the construction of military bases in the increasingly vulnerable territory. Congress, however, refused. Thus when Germany invaded Poland, Alaska had only one small military installation: Chilkoot Barracks, an army detachment near Haines. This post was more than a thousand miles away from the Aleutian Islands, the most likely Japanese target.

The war in Europe finally goaded Congress into action. Congress authorized three Alaska naval bases; work began at Sitka and Kodiak in 1939 and at Dutch Harbor in 1940. Congress dragged its feet on further Alaska appropriations until Germany invaded Scandinavia in the spring of 1940. The recognition that Alaska lay within striking distance of Nazi bombers spurred further activity, and during the summer of 1940 Army bases were laid out near both Anchorage and Fairbanks. A series of airfields linking interior Alaska with bases in southern Canada, along the so-called Northwest Staging Route, was authorized in 1940 and either constructed or expanded in 1941.

After the summer of 1940, the nation increasingly prepared for war, and as a part of the military buildup, millions of dollars were expended in Alaska to develop a stronger defense infrastructure. Because of that buildup, the U.S. government was fairly well prepared for war on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II.

Seward, at the southern end of the Alaska Railroad, was the linchpin for the only railroad–and the only year-round route–connecting the major shipping lanes with Alaska's two largest air bases. The town and bay, therefore, held enormous strategic value. In order to protect Seward, its port and rail facilities, and the enormous traffic that passed through, the U.S. Army Air Corps established Fort Raymond. [13] The fort consisted of the Seward garrison, just north of town; a dock and adjacent housing area for the stevedores, on the northeastern outskirts of town; and a fuel oil storage area, just south of the garrison. The fort was named for Capt. Charles W. Raymond, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Raymond had ascended the Yukon River to Fort Yukon in 1869. It was he who determined that the fort lay in Alaska; he convinced the Hudson's Bay Company personnel there that the post had been illegally established, and the traders vacated the post soon afterward. [14]

The Adjutant General of the Army Corps of Engineers authorized the construction of Fort Raymond on June 4, 1941. A small detail from Fort Richardson, near Anchorage, began preparing the site soon afterward. In late June, the first large troop complement left Seattle; it arrived in Seward on June 30. Construction began immediately afterward. Within two days, the fort site was being graded and leveled, and within a week, anti-aircraft gun emplacements were being constructed. [15] The first soldiers were from the Arkansas-based 153rd Infantry Battalion, which guarded ships and patrolled the town. Before long, they were joined by the 420th Coast Artillery, which manned the pillboxes on the beach and furnished the anti-aircraft unit; two port battalions, the 371st and the 260th; the 203rd Station Hospital Force; and the 29th Engineers Battalion. Later, in December 1942, troops from the 267th Coast Artillery (most of whom hailed from Pittsburgh and Baltimore) arrived in Seward. Some of those troops remained in town and were stationed at Fort Raymond. [16]

Living conditions at the fort were crude at first. Troops lived in tents, and until a mess hall was set up, soldiers marched to the supply ships for meals. Meanwhile, construction proceeded quickly; grading was completed by the end of July, and in August the Post Headquarters building was erected. Construction of other buildings followed. By the end of August 1943, the fort's buildings–in the stevedoring area, at the Army dock, the San Juan dock, and the main garrison–had all been completed. The main garrison featured a horseshoe-shaped parade ground; the nearby hospital area had three wards plus numerous associated buildings. [17]

Nine months after Fort Raymond was founded, on March 25, 1942, the troops had their only enemy encounter when they spotted a Japanese submarine within 2,000 yards of Seward's Army Dock. [18] Then, on June 3 and June 4, the Japanese Navy bombed Dutch Harbor. The raid resulted in relatively little damage to either Fort Mears (a U.S. Army post) or the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base. It did, however, underscore U.S. vulnerability to Japanese attack, and it was also followed soon afterward by the Japanese invasion of Attu and Kiska islands, at the western end of the Aleutian chain.

Perhaps in response to the raid, the U.S. Navy established a Navy Section Base at Seward. Located just north and west of the San Juan dock, the base was commissioned on July 31, 1942, and before long it consisted of four semi-permanent barracks, a seaplane hangar and ramp, and two piers: one 165 feet long, the other 100 feet long. [19]

Construction continued at Fort Raymond, as noted above, until the summer of 1943. No sooner was construction complete, however, than the fort had begun to lose its strategic value. Allied troops, in May 1943, successfully landed on Attu Island. Three weeks of hard fighting ensued, and by May 30, Japanese forces had been driven off the island. At Kiska Island, Allied forces launched a major assault on August 15. Surprisingly, they found no resistance; only later did they discover that the Japanese had evacuated the island in late July. Allied forces, once again, controlled the Aleutian Islands, and with action shifted to other theatres of operation, military commanders began to de-emphasize the importance of Fort Raymond and other Alaskan bases.

The Navy, perhaps because of higher priorities elsewhere, began to downsize its Seward facility even before the May campaign to retake Attu had begun. On April 1, 1943, the Section Base became a Naval Auxiliary Air Facility. Naval troops left town during June and July. On July 29, all naval activities at the facility were discontinued and the site was turned over to the U.S. Coast Guard. [20]

U.S. Army units began to leave Seward even before the Navy did so. In mid-March 1943, three battalions of the 153rd Infantry were sent to a camp in Mississippi, and before the end of the month the 420th Infantry had transferred to a camp in California. Other battalions of the 153rd Infantry continued to leave during the summer, and in October the 267th Artillery, which had been in Seward less than a year, took over the fort's administrative functions. [21]

By the spring of 1944, Alaska's defense network was considered sufficiently secure that further cutbacks were in order. On March 25, therefore, the Alaskan Department Headquarters of the U.S. War Department ordered that the entire Seward harbor defense network be dismantled. Two months later, all harbor entrance control post functions stopped. In response to those orders, most of those constituting the 267th Coast Artillery left Seward on August 28, 1944 and headed to a camp in Texas. A few troops, however, remained in town until 1945. [22]

After the war, Fort Raymond was a vacant government post until October 1947, when it was sold by the War Assets Administration to the private sector. [23] Just three years later, however, the military changed course when it established a U.S. Army Recreation Center on a small portion of the former fort. The recreation center, used by troops from Whittier and Fort Richardson, offered boats and barges for deep sea fishing. The center has utilized the site ever since. Sometime later, the U.S. Air Force moved to establish a similar facility. The two centers were merged in 1989; they now operate as the Seward Military Recreation Camp. [24]

World War II Activities in Resurrection

Bay

In order to protect Seward and the Alaska Railroad yards, the U.S. Army established outposts and bases on many of the islands and headlands of Resurrection Bay. Recognizing the bay's strategic importance, the military reserved most of the bay's islands and headlands during the summer of 1941; later in the war, it reserved thousands of additional acres overlooking the bay. Facilities, consisting of gun batteries, searchlights, communications sites, and supporting facilities, were constructed at many sites in and around the bay; many were built under the most trying of circumstances. Sites were reserved, and facilities built, on both sides of the bay and as far east as Chamberlain Point, overlooking Day Harbor. Because the focus of this study is the Kenai Fjords area, primary attention will be limited to the reservations and facilities that were located either on Resurrection Bay's west side or on islands within the bay.

Shortly after troops moved north to establish Fort Raymond, Army officials decided to move men and armaments to strategic points south of town. Caines Head, eight miles south of Seward, was the first site chosen because of its commanding position overlooking Resurrection Bay. A quick survey of proposed camp sites and road rights-of-way took place in July 1941, and on the last day of the month, troops from the 250th Coast Artillery moved from Seward to South Beach (also known as Minneapolis Beach) along with 155mm guns, ammunition, and supplies. The South Beach Cantonment of Fort Raymond was in operation. A road, intended to go from South Beach to North Beach, was already under construction by this time. But plans quickly changed; new plans called for all resources to be devoted to the construction of a gun battery at Rocky Point, a mile southwest of South Beach. The overwhelming demands for war materials brought many delays, so for the next several months, construction of the Rocky Point gun battery and the South Beach camp buildings fully occupied the soldiers. [25]

Meanwhile, the military moved to reserve the more strategic headlands and islands surrounding the bay. On August 29, 1941, the General Land Office withdrew seven area sites "for the use of the War Department for military purposes." The sites, and the approximate acreage reserved, included:

| * the Rocky Point-Caines Head area | 4,650 acres |

| * the Humpy Cove-Thumb Cove area | 900 acres |

| * Rugged Island | 1,020 acres |

| * Barwell Island | 36 acres |

| * Renard (Fox) Island | 1,510 acres |

| * Hive Island | 225 acres |

| * Cheval Island | 330 acres |

The military, as it turned out, used only the first four sites for defensive purposes; it bypassed Renard, Hive, and Cheval islands. [26]

In February 1942, the military authorized the construction of two six-inch batteries for the Seward harbor defense network. A locally appointed Harbor Defense Board recommended that the batteries be installed on Rugged Island and Aialik Cape. The latter point, at the south end of Aialik Peninsula, had not been withdrawn by the GLO the previous summer. Some authorities advocated the idea of a Cape Aialik battery, but others apparently did not, and by May 1942, the proposed battery site had been moved from Aialik Cape to Caines Head. Construction on the battery at the highest point on Caines Head began on July 20, 1942, while work at the southern tip of Rugged Island commenced on August 1. The Caines Head battery became known as Battery No. 293; the Rugged Island site became known as Battery No. 294.. [27]

In November 1942, Fort Raymond's commanding officer was ordered to construct two four-gun anti-motor torpedo boat (AMTB) batteries. By the following February, authorities had decided that the batteries would be constructed at Lowell Point and at the mouth of Fourth of July Creek. Both sites were at the northern end of Resurrection Bay; neither site had been withdrawn by the GLO in August 1941. The Lowell Point battery was completed as scheduled, but at Fourth of July Creek, a mobile gun base was operated on a temporary base but quickly abandoned.. [28]

During the construction of the Rugged Island and Caines Head batteries, the military decided to diversify the functions of both sites. Caines Head, for example, was chosen as the site for a joint Army-Navy Harbor Entrance Control Post (HECP) in November 1941. This post was necessary to coordinate and control shipping entering and leaving Resurrection Bay. The station, located in a temporary building, was ready for operation in August 1942. This post was later moved to a 37' x 83' concrete building at Patsy Point, at the southern tip of Rugged Island near Battery 294; in the same building, the military located a Harbor Defense Command Post. In addition, both the Caines Head and Rugged Island batteries were equipped with Radar Surface Craft Protector Units, which supplied advance intelligence to both the HECP and to the Fort Raymond Headquarters. South Beach (Caines Head) had sufficient barracks and mess facilities for 250 men, while the Rugged Island post had facilities to support an 88-man contingent. In recognition of these multiple functions, the Caines Head site was officially designated Fort McGilvray on March 25, 1943; that same day, the Rugged Island installation was designated Fort Bulkley.. [29] Construction at both posts continued for another year.

Military personnel occupied many other sites in and around Resurrection Bay. Searchlights were installed at Topeka Point (just north of Humpy Cove), Chamberlain Point (just south of Safety Cove, in Day Harbor), Carol Cove (on the northeast side of Rugged Island), Alma Point (on the northwest end of Rugged Island), Barwell Island, the east end of Thumb Cove, Caines Head, and Rocky Point. Radio stations were also widely distributed: sites included South Beach (Caines Head), Lowell Point, Barwell Island, Alma Point (Rugged Island), and Battery 294 (Rugged Island). A dock was constructed at North Beach (Caines Head), and barge-landing facilities were installed at Marys Bay (Rugged Island) and Topeka Point. To facilitate telephone communications, a submarine cable linked South Beach with Topeka Point and Topeka Point with Chamberlain Point; other cables connected South Beach to Rugged and Barwell islands.. [30]

The 250th Coast Artillery, recently arrived from a camp near Watsonville, California, was assigned to construct and operate the various installations south of Seward. They were the sole unit in the area from the summer of 1941 to December 1942, when the 267th Coast Artillery arrived at Fort Raymond. Soldiers of the 267th were soon deployed to various Resurrection Bay locations, and by October 1943 they were the sole occupants of the various remote posts. [31]

The soldiers stationed south of Seward witnessed few incidents of real or perceived enemy activity. In late March 1943, the Rugged Island Observation Post reported an unidentified submarine 15 miles off the island. The Navy, in response, spotted the same submarine 30 miles off the island and "that necessary action was taken." Six months later, a submarine periscope was reportedly seen in Day Harbor.. [32] The only other known "enemy action" took place when local fox farmer Pete Sather headed into the bay without signaling. Military authorities had told him to identify himself but he apparently forgot, and he was soon surprised to see artillery shells being lobbed his way. Soldiers put a searchlight on him and boarded his boat; Sather, however, was indignant over the incident. He figured that because he was carrying the mail, he should have been ensured a safe, unhindered passage.. [33]

By the spring of 1944, the various Resurrection Bay military facilities were largely finished; the Rugged Island installation was 90 percent complete, and the Caines Head facility was 99 percent complete.. [34] On March 25, however, troops were ordered to dismantle all of Seward's harbor defenses. All construction work stopped, and the military began removing the equipment it had so painstakingly placed at Caines Head, Rugged Island, and the other area sites. The dismantling process took several months; during that time, the two big six-inch guns were shipped to locations in South Dakota and southern California. By August 28, 1944, most of the existing troop complement had left the area and headed south. The once-bustling military sites were now abandoned.. [35]

After the war, government officials moved to make the islands in the harbor defense network available to the public. On November 6, 1945, the military declared the land surplus, and on November 28 it was assigned to the Department of the Interior. Interior officials initially moved to return Renard, Hive, and Cheval islands to the public domain; all had been included in the August 1941 withdrawal but had not been subject to military improvements. These islands were returned to the General Land Office by July 9, 1946, but it took more than eighteen additional months for a public land order to be signed that formally revoked the August 1941 military withdrawal for these islands.. [36]

The War Assets Administration (WAA), given the task of evaluating the defense network "betterments" (improvements) at the other Resurrection Bay sites, noted that they had an acquisition cost of $3,424,632. The vast majority of the improvements, however, had no alternative uses; in April 1946, therefore, the WAA declared that the improvements had a "fair value" of $25,000. On August 22, 1946, Bureau of Land Management staff visited the site. The agency noted that the improvements were "comprised mostly of T-buildings, Quonset and Butler huts, and at one point a report from the custodian shows an 80 per cent loss of buildings caused by their collapse from the weight of heavy snow." A month later, Interior Department personnel made a Survey for Disposal of Surplus Property at three locations along the bay's western side; they noted 16 buildings and a small dam at South Beach, 5 buildings at Rocky Point, and 2 huts, a dock and a warehouse at North Beach.. [37]

These lands were no longer valuable to the military, so officials moved to transfer them back to civilian control. In September and October 1946, Barwell Island and Topeka Point, respectively, were abandoned. In September 1947, representatives of WAA and BLM tentatively concluded that the remainder of the harbor defense network should either be abandoned or donated to the Department of the Interior. They reached this conclusion because no one had shown an interest in using the property and because none of the remaining improvements had commercial value for use at an off-site location. On October 29, the WAA authorized the BLM to abandon all structures and improvements at Rocky Point, South Beach, North Beach, and Rugged Island and to return all lands covered by the August 1941 executive order to the public domain. The public land order that carried out the WAA's decision, however, was not issued until 1962. By that time, the new State of Alaska had already shown an interest in acquiring these lands, so the land order that returned the parcels to the public domain specified that the state had first selection rights. The state, in fact, moved to acquire land surrounding Caines Head. It also made claims to most of the other parcels containing Harbor Defense installations. Some of those parcels have been transferred to state control, but others have remained under federal jurisdiction.. [38]

In April 1962, the State of Alaska filed for a 13,800-acre parcel containing Caines Head. In May 1964, it received a patent to the North Beach, South Beach, and Rocky Point sites; that same year, the BLM tentatively approved the state's application for the remainder of the parcel.. [39] In 1971, the Alaska Division of Parks (which had been created just a year earlier) selected some 1,800 acres and established Caines Head State Recreation Area. Three years later, more than 4,000 acres was added to the park; its new area was 5,961 acres. No recreational development, however, took place at the site until the mid-1980s. Since that time, rangers and volunteers have constructed trails, built a public use cabin and ranger station, interviewed veterans who served there, and conducted initial interpretation efforts.. [40]

The rest of the harbor defense network, returned to the public domain in 1962, has been ignored in recent years. Aside from the Caines Head area, no organized efforts have been made to either protect or interpret what remains of the World War II-era improvements.. [41]

The Outer Island Station

The Aircraft Warning Service, part of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, received authorization in May 1940 to begin setting up a network of Alaska detector sites. The military's Western Defense Command initially proposed four such sites, and in December 1940, authorization was granted to construct four fixed sites and one mobile site. Three months later, stations were authorized at a minimum of seven additional locations. These stations were designed to give a minimum warning to the approach of hostile aircraft at the territory's three largest Navy bases (at Dutch Harbor, Kodiak, and Sitka) and its two largest Army bases (at Anchorage and Fairbanks). The Western Defense Command, up to this point, did not propose any AWS detector sites in the Seward area.. [42]

|

| The Aircraft Warning Service staffed a detector-site station in the Pye Islands (shown in foreground) from 1942 to 1944. M. Woodbridge Williams/NPS photo, in Alaska Regional Profiles, Southcentral Region, July 1974, 35. |

|

| This Army Corps drawing made in 1942, details the layout of the Aircraft Warning Service camp on Outer Island. Army Corps of Engineers Collection, NARA Anchorage. |

Following the declaration of war in December 1941, the Commanding General of the Alaska Defense Command was given the authority to immediately construct detector sites as determined by the tactical situation. Soon afterward, new detector sites were established surrounding each major air base in Alaska. Then, in October 1942, the Alaska's Air Defense Plan was expanded to include Very High Frequency stations for local communication with certain friendly aircraft during periods of general radio silence. The construction of the Outer Island Aircraft Warning Service Station, in the Pye Islands 80 miles southwest of Seward, was constructed in response to one of these two initiatives. The station was one of the more than 20 Alaska AWS stations which were either operating or under construction by the end of 1942.. [43]

Contemporary maps and drawings suggest that the Outer Island AWS station was first proposed in June 1942.. [44] By August a small, temporary construction camp had apparently been established at the island's southeastern tip, 325 feet above sea level. Plans were laid out that month for a detector-site complex large enough to house 150 men. The proposed camp, which would be laid out on a south-facing hill, surrounded a small swamp. The camp would consist of a 50-man headquarters building, two 50-man barracks, three 16' x 36' Quonset huts (for materials storage), three latrines, a cold storage building, a powerhouse, and the detector site. Water would be provided by two concrete-lined storage tanks, connected to the camp by water lines. Either underground or overhead power lines connected the powerhouse to each building; the entire camp would be connected to the north side of the island by a 0.6-mile dirt road. The proposed Kitten Pass landing site, at the island's northern end, would have a dock, where two additional 16' x 36' Quonset huts were proposed; the dock, located at the base of a cliff, would connect to the road by means of a short tramway and stairway.. [45]

Construction on the permanent camp closely followed the outlined plans. Much of the camp was built that winter; the communications gear was installed by the Signal Corps, while the buildings and supporting infrastructure were supplied by the Corps of Engineers. The detector site was fully operational by March 1943. By October, the camp had been completed. During that summer or fall, the island saw its only "action" when the commander of a U.S. ship convoy ordered his crew to open fire with its 20mm guns. The detector-site crew, clearly alarmed at the assault, jumped behind sandbags and radioed that they were under attack by a Japanese submarine. The convoy commander was obviously unaware that the island had a fully staffed AWS station. Fortunately, no one was hurt in the incident.. [46]

|

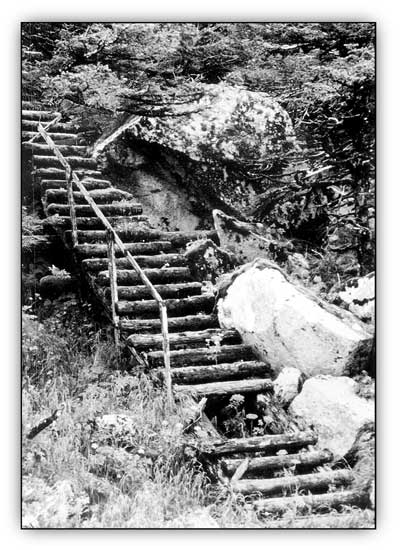

| The Kitten Pass stairway, built by military personel in 1942 at the north end of Outer Island. M. Woodbridge Williams photo, NPS/Alaska Area Office print file, NARA Anchorage. |

Little is known about the lifestyle led by the soldiers stationed on Outer Island. One anecdote suggests that many soldiers, either out of frustration or boredom, killed hundreds of sea lions at their rookeries while out on patrol. Another account states that Outer Island soldiers, like soldiers in many remote areas, were lonely; they thus welcomed the opportunity to socialize with others. Josephine Sather, who lived on nearby Nuka Island, recalled that:

During the war, many young servicemen came here. Many times we've had four or five of them sitting or lying on the carpet with books and newspapers all around them, while still others, perhaps in a real home for the first time since they left their mothers' homes, were writing long-delayed letters to their families. In the summer, when my flowers were at the height of their glory, the first thing these boys would say was "Oh! I wish my mother could see all this!" Then, "May I write a letter? This time I really have something to write about."

In the winter they'd say, "Gee, it's good to get off the boat for a few hours!" I'll always remember one lad who sat on the couch not saying a word, stroking the silky draperies ever so gently, his eyes misty and his thoughts no doubt of home.... They called me mom; and the good will and kind memories they carried away from my home are worth more to me than any monetary consideration.. [47]

It is not known how long soldiers remained on Outer Island. They probably remained at their post until the spring or summer of 1944; then they, like those who were serving at the various Resurrection Bay posts, vacated the area and moved to camps in the States.

The area, not having been withdrawn by the War Department, remained part of the public domain for the duration of the war. When the soldiers left, military officials apparently removed the camp's communication gear and other valuable equipment. They abandoned the various buildings, however.

The camp was quickly forgotten and its material remains soon deteriorated. When the U.S. Geological Survey studied the island in 1951, in conjunction with a topographic map of the area published that year, it made no indication of buildings or other cultural features.. [48]

For the next several decades, few visited or paid attention to the old World War II site. In July 1976, Nina Faust visited the landing site at the northern end of the island as part of a bird survey. While there, she found many remaining artifacts. She noted that:

Remains of an old rail supply line, apparently installed by the Army to bring supplies from the water to a ladder at the base of a trail, are now bent and rusty. Portions of an old, rotten wooden ladder, traversing moss-covered boulders and crevices, still remain. The ladder ascends a steep hillside to an obscure footpath that crosses spectacular cliffs to an observation post on the island's southern plateau.. [49]

Excerpts of Ms. Faust's journal from that visit provide an excellent description of both the landing and camp area:

Friday, July 2, 1976. [We were] left on Outer Island of the Pye Islands to recon the area. We established our camp at the base of a wooden ladder leading to an old WW II bunker. It took some digging to get a level tent area for our supply tent and sleeping tent.

Saturday, July 3. At noon we took off up the mountain above our camp. The bunker trail is very overgrown in some places, very evident in others. The ladder is very rotted in most places where it is even visible. We were not able to trace the trail very far going up mainly because our objective was to reach the top. On the way down we encountered the army trail which indicates that it contours around the side of the hill.

Sunday, July 4. Followed an old army trail to the bunkers on the south point of the island. The old WW II trail was built on a contour around the east side of the island over very steep cliffs and gorges–a very difficult route to have built. We followed the trail the best we could climbing up rotted wood ladders, pushing our way through thick salmon berry bushes and alder. Several times we lost the trail because the vegetation was so thick. Other times we came to a temporary impasse at steep rock walled gorges where the trail once had some kind of suspension bridge. Bits of rotted rope hang on a rusted bracing spike. A giant rusted eyebolt is pounded into the rock before the gorge.... At this first gorge, we were forced to climb up the steep slope pulling ourselves up with vegetation as best as possible, until we were finally higher than the impassible part we had encountered. Further along we lost the trail entirely where it had simply slid down the hill, probably during the '64 earthquake.... Our destination was the plateau above the large puffin colony and the bunker was finally made five hours after starting. The area of former habitation was dangerous walking. Salmonberry bushes were waist to chest high. Stepping on rotten boardwalks between the six buildings was easy to do–so was falling through. There is one quonset hut, one small lookout shelter right next to the cliff, and about 4 other large bunkhouse, dining hall, work area buildings placed around among the trees. They are slowly collapsing as the wood rots away. As there was really nothing left inside, I did not risk the rotten wood. We know they had a generator, probably a well and a small reservoir. It appears to have been a good-sized detachment.. [50]

Many of those who have visited the island since then have also focused on the decaying resources at the north-end landing site. Marge Tillion, who lived on nearby Nuka Island during the early 1980s, noted that it was still possible to ascend the stairs rising from the beach. In 1989, archeologist Mike Yarborough noted that the site consisted of "three flights of log stairs, iron rails, and drilled boulders on or adjacent to a boulder beach at the northeast corner of the island." Yarborough, who was unable to make a land survey, also noted a road cut that "runs up the mountain slope along the southeastern coast of the island" and located an iron cart beside the road.. [51]

National Park Service ranger Mike Tetreau visited the island in 1994. He noted that in the old camp area, salmonberries and other overgrowth had done much to obscure the visible resources. He recalled, however, seeing the remains of at least two large bunkhouse structures and at least two smaller buildings. Of these buildings, perhaps one wall remained standing; all the rest were collapsed. One of the buildings was buttressed with earth mounds. The road that once connected the camp to the landing area was almost if not entirely obscured.. [52]

|

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, 1920. The Rockwell Kent Legacies. |

kefj/hrs/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002