|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 2:

LIVING ON THE OUTER KENAI PENINSULA

The east coast of Cook Inlet is called the Kenai Peninsula, a land with a backbone of glaciers sliding icy spines into the Gulf of Alaska where Eskimo once occupied the fjords facing the open sea. [1] — Cornelius B. Osgood, 1937

The Chugach and Unegkurmiut

|

| Map 2-1. Historic Sites-Nativge Lifeways. (cick on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Kenai Peninsula's earliest inhabitants were a people in transition. Living on a narrow strip of land between the edge of the Kenai Mountains and the surge of the Pacific Ocean, the Natives of the outer coast constituted one of the easternmost groups of Pacific Eskimo. The archeological data suggest that most of the sites known today are about 800 years old. [2] Only some of these villages were still inhabited at the time of Russian contact; even fewer existed until the twentieth century. Many speculate that these coastal people migrated to the coast from Kodiak Island or the Alaska Peninsula and traded along the length of the Pacific coast.

The Native inhabitants of the Pacific coast of the Kenai Peninsula region are called the Alutiiq Chugach. Variants of the name Chugach occur in Russian, American, and European ethnographic studies and is generally inclusive of Pacific Eskimo who lived from Cape Elizabeth to the eastern coastal areas of Prince William Sound. By some historical accounts, the name Chugach is a derivative of the Russian-Eskimo name for Prince William Sound and the Chugach Islands near Kachemak Bay. Traveling between the two regions, the Natives crossed a portage through one of the fjords to arrive in Kachemak Bay near the Chugach Islands. The prolific, though not always reliable, Russian chronicler Ivan Petroff stated that the name "Chugach" was a Russian version of the tribal name of Sh-Ghachit Shoit (the latter word means simply "people"). [3] The scientist and naturalist William Dall called them Chugachmiut, placing a "miut" at the end of the word to imply "dwellers of."

Many anthropologists maintain that the Eskimo of the outer Kenai Peninsula, the Unixkugmiut or Unegkurmiut, were a separate people from the nine Chugach subtribes of the larger Prince William Sound island region. It is presumed that the Unegkurmiut's affiliation lay more with the inhabitants of Kodiak Island. The Unegkurmiut are believed to have once inhabited a larger portion of the Kenai Peninsula and may have been one of several other unknown Pacific Eskimo subtribes. [4] Frederica de Laguna, who visited the region in the 1930s and documented a dozen sites, contended that Kenai Peninsula inhabitants, whose range extended from Puget Bay to Cook Inlet, were not tribesmen of the Chugach. [5] Historical references, in part, support this view. Baranov referred to the Natives in his charge at Resurrection Bay as inovertsy meaning "men of other faith." [6] Carl Merck, the naturalist on Captain Joseph Billing's 1790 expedition, met local inhabitants in the vicinity of Nuka Bay and learned they were called Chugachi. These inhabitants made a point of warning Merck of other Natives who had the same name. [7] Davydov, who visited the area shortly after 1800, made a connection between the Kenai coastline and the name and territory of the Native inhabitants:

In Voskresensk (Resurrection) Bay, where the Chugaches live, there is also an artel; further on is also one in Chugatsk Bay, or Prince William Sound, on Nuchek Island. From time to time the inhabitants of the Copper River come here in huge boats to see the hostages that have been taken away from them, and to sell the furs and raw copper which they have brought with them. [8]

|

| A woman of Prince William Sound Alaska Purchase Centennial Commission. Alaska State Library, photo PCA 20-249. |

In the 1830s Ferdinand Wrangell wrote on the ancestral lineage of the Chugach, drawing an association between the people of the outer Kenai coast and Kodiak Island. Wrangell maintained that the Chugach were descendants of the people living on Kodiak Island.

The Chugach were driven from the island of Kadiak after internal strife there and eventually reached the site of their present settlements on the shores of Prince William Sound and west as far as the entrance to Cook's Inlet. It is certain that they are of the same tribe as the Kadiaks. [9]

Wrangell also noted that the residents of both Kodiak Island and the Gulf Coast had similar clothing in contrast to other Alaska Natives he had encountered. He observed, "they do not dress in reindeer skins, like the other tribes of these regions, but make their parkas (winter garments) from birdskin and their kamleis (summer garments) from the intestines of whales and seals." [10]

The following observations, published in 1836, support Wrangell's views and give insight into what people knew and recorded about the region.

Two tribes are found, on the Pacific Ocean, whose kindred language, though exhibiting some affinities both with that of the Western Eskimaux and with that the Athapascas, we shall, for the present, consider as forming a distinct family. They are the Kinai, in and near Cook's Inlet or River, and the Ugaljachmutzi (Ougalachmioutsy) of Prince William Sound. The Tshagazzi, who inhabit the country between those two tribes, are Eskimaux and speak a dialect nearly the same with that of the Konagen of Kakjak [Kodiak] Island. [11]

Petroff thought that the origin of the people was evident in their preference for skin boats rather than wooden dugouts. Wood was the technology so preferred by the Tlingits, who were the southern neighbors of the Chugach. Petroff's observations are worded in such a way as to suggest that he reached these conclusions almost by a process of elimination. He noted, "The exclusive use of the kaiak or bidarka in this Alpine region, with dense forests and dangerous beaches, can only be explained by the emigration of the people from other regions devoid of timber." [12]

Finally, Birket-Smith stated that his informant in the 1950s would call himself a name meaning "Eskimo of Prince William Sound", drawing a marked distinction between he and those from Seward, Nuka Bay, and points west. [13]

Other anthropologists, however, present a different lineage for the people of the outer coast. Hassen suggests that the Chugach were kinsmen of the Unegkurmiut of Resurrection Bay, Nuka Bay, and Port Graham, implying a marked regional and perhaps ethnographic distinction. [14] There is also the speculation that the Unegkurmiut lived well into the southern portion of Cook Inlet only to be pushed back by the Koniag. [15] At the time of Russian and European contact, the territory of the Dena'ina included all of Cook Inlet except for the southern end of the Kenai Peninsula and outer coast. [16] Captain James Cook met Natives near North Foreland, which lies south of present day village of Tyonek, and there he observed a resemblance to others whom he had encountered on the Gulf of Alaska coast. He noted that "I could observe no difference between the persons, dress, ornaments, and boats of these people, and those of Prince William's Sounds, except that the small canoes were rather of a less size, and carried only one man...." [17]

The above statements suggest that there is little consensus and even less descriptive material on the people who inhabited the remote Kenai coast. Many agree that the Unegkurmiut were an obscure people. [18] Oswalt epitomized what scant information existed by stating, "They were Suk-speaking Eskimos whose roots were shallow and whose success was moderate." [19]

Despite these different viewpoints, many observations can be made about the Kenai coast inhabitants from the records of the Russian, English, and Spanish mariners and traders and the history of the of the Dena'ina, Koniag, Chugach, and Tlingit. Looking at the outer coast inhabitants from the perspective of their neighbors gives an insight into the identity of these people. Most of the ethnographic research for this context is based on the Chugach, for whom there is more documentation. From general prototypes of Chugach land use and subsistence, some inferences can be made about the lifestyle of the Unegkurmiut.

A People Few in Number

Alexander Walker, a British soldier and fur trader, provides one of the earliest descriptive accounts of the Chugach.

The Inhabitants of Prince William Sound are a pensive phlegmatic People, without the least disposition for enquiry. Their countenances express none of their passions, but are full of a kind of unmeaning good natured Stare. Their complexion is Olive. In their Features they much resemble the Inhabitants of Nootka, having broad round faces, high Plump Cheeks, small flattish Noses, large Nostrils, small black Eyes. The Eyes of many of them are sore and watery, which probably arises from the smoke of their Houses and the glare of Snow. Their hair is black, and is generally worn short. Some of them shave or cut their beard, and others allow them to grow long. [20]

Walker's observations, made while on a voyage with James Strange to Prince William Sound in August 1786, supported the claim that the Chugach were few in number.

This part of the World is either very thinly inhabited, or at the Season, in which we visited it, the greater part of the People had retired to some other place.... For even allowing that a great proportion of the Inhabitants had gone into the interior parts of the Country for the sake of Game, still if Prince William Sound were the residence of many people during the winter, it is likely, that in traversing so many places we would have fallen in with more of their Houses. We did not [altogether] see above one hundred People.... If detected they surrendered their plunder very quietly, but showed no marks of being conscious that their conduct had been improper. We several times discovered them attempting the Ironwork of the Vessels.... [21]

The population size of the Chugach at the time of Russian contact is unknown, though Oswalt estimated that by 1800 there might have been only 600 inhabitants on the southern Kenai Peninsula. [22] The number of inhabitants along the coast fluctuated depending on who conducted a census at the time. Russian ethnographic studies, a by-product of the numerous censuses taken in the 1800s by the Russian-American Company and the Russian Orthodox Church, tended to count the Kenai inhabitants as one and the same with the Chugach. Perhaps this tendency represented an association with Chugach Bay or the many variations in name given for the people who traveled along the coast of the Gulf of Alaska. The practice may also have been the result of the relatively low number of inhabitants on the Kenai Peninsula coast in addition to the Russian practice of consolidating peoples and forming large hunting crews from many coastal areas. It may also have been simply a matter of convenience. When Ludwig von Hagemeister, the Russian Navy captain, ordered a census in the early half of the nineteenth century there were 477 Native Chugach and Oughalentse in the Prince William Sound region as compared to 1,471 people along Cook Inlet. [23] Teben'kov reported in the Notes to his 1852 atlas that "The Native population of Kenai Bay amounts to 1,000 souls of both sexes, they consist of a separate tribe, belonging to the Chugaches or to the Kad'iaks." [24] This surprisingly high number of inhabitants for the years following the smallpox epidemic is counterbal-anced by Wrangell's earlier estimate in the 1830s that the Chugachiks, "as they called themselves," consisted of approximately 100 families. [25]

Late nineteenth century studies conducted under the auspices of the U.S. Department of the Interior also categorized the people of the Prince William Sound area as Chugach. In 1875, Dall enumerated the Chugach and observed that their living conditions were in a state of decline. He noted, "Being in localities where there is less fishing practicable, these tribes live principally by hunting and trapping. These are amiable and harmless, but in a savage condition." [26]

Warfare and Trade

As mentioned above, Wrangell maintained that the people of the outer coast originated in Kodiak. In the early and middle 1700s, prior to Russian contact, intertribal fighting alienated the Chugach faction to Prince William Sound and "west as far as the entrance to Cook's Inlet." [27] This meant that settlement along the fjords on the Pacific coast was relatively recent at the time of Russian exploration. The Athapaskan Dena'ina to the north invaded and occupied the southern and coastal region surrounding Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay, forcing the Eskimo south. Another theory maintained that the Chugach occupied Prince William Sound prior to Dena'ina settlement in Cook Inlet. [28] There were also territorial pressures from the Koniag on Kodiak Island to the southwest, and the Tlingit and Eyak to the southeast of Prince William Sound. [29]

Many Chugach stories told of conflict with the Koniag and the Tlingit, recounting the intensity and nature of intertribal raids. [30] As Birket-Smith documented in the story "The Fight with the Dena'ina," in the years prior to Russian contact many villages throughout the Kenai and Prince William Sound areas banded together to fend off a common enemy. In one decisive battle, men from the villages of Tatitlek, Nuchek, Chenega, Montague, Day Harbor, and Qutatluq (near Seward) defeated the Dena'ina in Cook Inlet. [31] Another story focused on atrocities committed against the wives of seal hunters on Kodiak.

When a group of men went seal hunting, they left their wives at Johnstone Point [on Hinchinbrook Island] for safety. A war party from Kodiak Island came. The women, not wanting to reveal that no men were present, donned mustaches of bear fur. One woman leaned over the edge and dropped her mustache, alerting the war party to the women's ruse. The Kodiak Eskimos then climbed the rock and captured or killed the women. Months later the seal hunters successfully avenged the Kodiaks. [32]

Despite enmity and natural geographic boundaries that kept the Athapaskans and Koniag at somewhat of a distance, the Chugach traded extensively with all their neighbors, acquiring caribou skins and copper from the Ahtna and snowshoes, hatchets, and wedges from the Eyak. [33] Intertribal trade with the Koniag, Dena'ina, and Tlingit provided an exchange of sea and land mammal pelts. Kodiak residents also sought dentalium shell beads and spoons from the Chugach. [34]

|

| A group of Natives by a barabara, 1901, above Seldovia. Anchorage Museum of History and Art, photo B91-142. |

Villages

The coastal topography of the Kenai Peninsula is similar to that of the Aleutian Islands, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound. Travel along the southern Kenai coast was common, as were longer expeditions to Prince William Sound, Kodiak Island, the Barren Islands, and Cook Inlet. Taking advantage of stopping points and layovers in protected coves and passes, the Kenai coast inhabitants managed to access all reaches of the peninsula in a series of stages. For journeys to Kodiak Island, the Barren Islands served as a convenient place to rest and take shelter. [35]

The use of portages, trails, and temporary camps provided an alternate route during stormy seas and inclement weather. Overland baidarka portages served as a back door to hunting and trade corridors on the peninsula. As noted in Chapter 1, a series of trails linked the coastal and inland regions of the Kenai Peninsula. Routes linked Prince William Sound and the head of Resurrection Bay with Turnagain Arm. These routes provided year round access to the coast, especially for the Dena'ina who were less adept at navigating in the open waters of the Pacific Ocean.

In general, the Pacific Eskimo identified with individual villages and village groups, rather than one large collective. Oswalt described village makeup and membership as "fluid" with subtribes having affiliation with one or more villages. [36] Archeological investigations in the 1930s by de Laguna and Birket-Smith in Prince William Sound detected small populations and scattered village sites despite an apparently rich resource base. Oswalt attributed sparse village distribution of the Unegkurmiut to a relatively unproductive environment despite the region's resource potential. [37] As noted in "The Fight with the Dena'ina", Chugach raiding parties from Prince William Sound ranged in size from twelve to twenty-eight men per village. [38] Others including Dall maintained that the fishing was sparse, especially in the lands closer to Prince William Sound. Hunting was the main source of food for the Chugach villages.

Like the Koniag, the Pacific Eskimo were master mariners and hunted at sea. To maneuver small boats in open waters demanded a lifetime of skill. It was possible that the Unegkurmiut, like the Chugach, hunted at sea with bows and arrows and pursued whales with darts and harpoons. [39] Whales migrated along the open waters of the rugged coast, and hunters used the high rocky perches to spot the large mammals. In a world oriented primarily towards the sea, the Chugach depended on the open water for subsistence, a haven from enemies, and communication with other villages. Often one village, as in the case of Yalik (in Nuka Bay) and perhaps others, was self-sufficient and independent with its own chief. [40]

The Chugach divided the year and their activities between temporary transient summer camps and permanent winter villages. Surrounded in most areas by the lush growth of coniferous rainforest, the Chugach constructed rectangular-shaped winter dwellings of wooden planking insulated with packed moss. Portlock gave one of the most explicit descriptions of Chugach houses:

Those I have seen are not more than four to six feet high, about ten feet long and about eight feet broad, built with thick plank and the crevices filled up with dry moss.... The method they use in making plank is, to split the trees with wooden or stone wedges; and I have seen a plank twenty or twenty five feet long, split from a tree by their method. [41]

The Unegkurmiut established village sites on the shores of bays with close access to bodies of water including lagoons, streams, or bays. Given an alternative, land travel was minimal. Sea routes provided easier access to coastal villages. Villages located on elevated shorelines provided commanding unobstructed views and a ready escape route by sea in the event of attack. Higher observation points were used to spot the approach of game and unwelcome strangers. [42] de Laguna contended that the need a for strategic village location outweighed other geographic factors including proximity to salmon streams and shellfish beds typically found at the headwaters of bays. For these reasons as well, the Chugach tended to place villages near the entrances to bays, rivers, and recessed fjords.

|

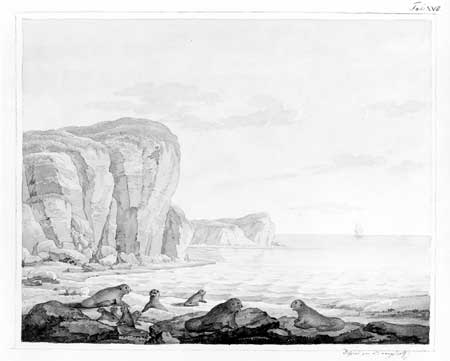

| View of rocky beach with family of sea otters, from Georg Langsdorff, c. 1805. Bancroft Library. |

Seasonal fish camps were located near streams and rock outcrop islands. These camps and retreats were also located on protected bays. For these short periods of the year, however, more emphasis was placed on making camp near salmon rich streams than on high defensive points. [43] During these months village members moved away from the permanent settlements to fish for salmon and halibut and hunt whale. [44] Chugach summer dwellings varied from bark covered shelters with inverted skin boats for roofs to sturdier multi-family rectangular wooden houses. [45]

Village related structures and land use typically included cache islands for food, burial sites, portages, and offshore island retreats in times of attack. Secondary land use sites included sea otter hunting camps, garden sites, and egg, feather, and timber collecting sites. [46] Burial sites also had association. The Chugach covered the faces of their dead with death masks. In some instances the masks were placed next to the individual. The imagery on the mask depicted "family spirits pictured in animal or human forms." [47]

Other features, notably Sitka spruce trees marked and scarred by the harvesting of slabs of bark, constitute another indicator of cultural land use. Known as culturally modified trees, these trees bear the mark of where Chugach stripped and carved out patches of bark, both as a food source and as building and artisan material.

The number of actual villages that existed at any period in history along the coast is unknown. Determining locations for these villages has historical importance because many of these same sites continued to support both seasonal hunting crews and other resource uses. Site documentation profiled in 1991 for the Chugach Alaska Corporation supported a relationship between the location of earlier village sites and the later use of these areas as a base for seasonal hunting and trapping parties. [48]

While documentation of village sites and names for the outer coast within parklands is sparse and largely unknown, some village locations have been reported and others recorded. Known villages sites along the outer Kenai coast include: an unnamed settlement in Aialik Bay; Yalik Village in Nuka Bay; Nuna'tunaq in Rocky Bay; Kogiu-xtolik in Dogfish or Koyuktolik Bay; Axu'layik at Port Chatham; Chrome, or "To'qakvik" at the entrance of Port Chatham; the summer village of Nanu'aluq near the location of the Russian fort Alexandrovsk; and Palu'vik at Port Graham. The settlement in Aialik Bay may have been near Verdant Cove (south of Verdant Island) or at another point along the coast. [49]

Yalik village located in Yalik Bay is the only village on the coast within park boundaries to survive by name into the historic period, although historically it had other names. [50] Townsend suggests that the villages of Akhmylik and Yalik were one and the same. [51] The village of Yalik appeared in Petroff's 1880 census and is listed as Eskimo. de Laguna referred to the village by name in addition to two other abandoned settlements: one in Aialik Bay and a second known as Nuna'tunaq in Rocky Bay. [52] According to contacts she had along the coast, village residents were called yaleymiut, "an independent tribe with their own chief." [53]

|

| Native paddlers rest in their baidarkas near Seldovia, c. 1916. Anchorage Museum of History and Art, photo B91-9-143. |

Acculturation and Change

Many questions surround the decline of the Chugach and the events that led them to abandon their coastal homes in favor of larger villages. Equally, the fate of the Unegkurmiut is unknown though it is likely that several environmental and social factors common to the Kenai and Alaska peninsulas contributed to the decline in population and loss of villages. Russian influences and acculturation that so altered the Chugach and Dena'ina populations in general, including disease, hostilities, and relocation, directly affected the inhabitants of the outer Kenai coast. As a point of comparison, the Native population of Kodiak Island, which once lived in sixty-five different villages, had been consolidated into just seven by 1841. [54]

Russian expeditions based from settlements in the Aleutians and on Kodiak Island began to penetrate the outer Kenai coastline and Prince William Sound in the 1780s. As Russian promyshlenniks pushed eastward, Kenai Peninsula inhabitants fell in the path of hunting parties. Khlebnikov reported that Baranov sent the first hunting crew from Kodiak Island towards Yakutat Bay arriving in 1794. Baranov traveled to Prince William Sound to personally induct several Chugach into the hunting party. [55] Okun noted that the Russian-American Company had less involvement with Kenai and Chugach, rarely calling upon them to trade or work--Russian labor documents typically referred to them as "independent tribes." [56] However, many other references pointed out that the hunting parties leaving Kodiak Island passed along the outer Kenai coast on their way to Prince William Sound. Sarafian, for example, notes that

In 1792, the Russians first attempted to employ Chugaches to hunt sea otter, but out of fear the Natives ran away and hid. By 1803, the company with the aid of gifts had induced the Chugaches of Chugach Bay to hunt sea otter and every summer thereafter about 60 Chugaches hunted this animal for it. At the end of the season, the company paid them the fixed price for their pelts in beads and tobacco. [57]

Often as many as 500 baidarkas participated in the hunting expeditions. Between 100 to 200 baidarkas traveled to other parts of the coast of Kodiak Island and along the shore of Alaska recruiting men from among the Kenai and Chugach. The constant shuffling and moving of residents led to the demise of many villages.

|

| Hunting baidarka. From the collection of Ball, Flamen. Alaska State Library, photo PCA 24-99. |

Baranov felt uncomfortable with the practice of consolidating villages and accused Shelikhov of "playing politics by asking [him] to hire them to leave their homes and face the unknown in the new settlements." [58] The Russians were very concerned by the drop in population. The number of available hunters decreased in the late 1700s, which Baranov attributed to the constant relocation of villages. Baranov noted that "From their number, many are killed or drowned, too old or too young, or rotten from disease well known here." [59]

Heiromonk Gideon, a church envoy to the Russian colonies, noted in the early 1800s that hunting crews leaving Kodiak for Prince William Sound and beyond, typically took on recruits from the outer Kenai Peninsula. [60] After stopping at Fort Alexandrovsk near Cape Elizabeth, crews regrouped and traveled southeast along the coast. Near Resurrection Bay, crews awaited envoys from Voskresenskii Redoubt who joined them on route. Once at Nuchek, the leaders sized up the crew, leaving the weaker men to hunt in Prince William Sound. The others headed south. This practice left many villages essentially deserted in the summer. [61]

Heiromonk Gideon recorded the drop in the number of baidarkas that made up these hunting parties, pointing out that at one time 800 boats traveled the coast together. [62] By 1799 the number fell to 500 and within another five years only 300 baidarkas gathered at the call.

Shelikhov regarded the land on the Kenai Peninsula as rich with an abundance of birds, fish, and timber. [63] The Russians expedited crews from Kodiak Island to trap birds along the coast and on the islands between the mouth of Cook Inlet and Resurrection Bay. [64] These parties included people relocated from the Aleutians as well as Chugach and Kenaitze who were physically unable to participate in the hunting parties. [65] Forts at Kodiak, Nuchek, and Alexandrovsk on the outer peninsula were stopping points for crews gathering bird feathers and for hunters to join hunting parties.

Bird hunting was especially important to the Natives. Russian policy prevented Natives from making fur parkas. The Russians confiscated as many furs as possible for trade, leaving the Natives to fend off the winter cold with bird skin parkas. Davydov observed that "They are in general forbidden to wear clothes made from expensive furs, which they are obliged to give to the company. They are allowed to make clothes from hares, marmots, squirrels, and birdskins." [66] On the return trip to Kodiak, many of the hunters also stopped on the islands near Resurrection Bay to assist with the bird hunt. [67] Davydov related, "In the spring the Chugach also collected and preserved eggs for Russian consumption; in the winter the Company requested sheep and marmots." [68]

In one account of Russian traders leaving Nuchek Bay, the value of a fur parka is illustrated when a Native couple were obliged to part company:

... One of the Natives was persuaded to accompany the ship as guide; the wife of the man was furnished with a quantity of beads to console her for the absence of her husband but when the ship was ready to sail the man took off his only garment a marmot parka and gave it to his wife to keep; the commander then fitted him out with an Aleutian bird skin parka and a canvas shirt. [69]

Smaller, remote villages like those likely to have existed on the Kenai coast had little chance of survival given the demands of the Russian companies. After a grueling summer at sea, many men returned to their villages in the late fall. At that time, food and clothing needed to be stockpiled for the winter months ahead. After a few seasons of this regime, many villages fell into ruin. By the 1830s Wrangell observed that because of extensive intermixing between the people of the Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound, their individuality had deteriorated.

Disease further annihilated village structure on the Kenai Peninsula. The first recorded epidemic spread through Kodiak Island and Cook Inlet in 1798. [70] The smallpox epidemics from 1835 to 1840 and the later ones in the 1860s decimated an enormous proportion of the Native population along the Gulf of Alaska coast.

The smallpox epidemic of the 1830s was at its most virulent from 1836 to 1838. It apparently began with the Tlingit and moved west to the Dena'ina. [71] By some estimates one in three died, and many of the survivors were left maimed or blind from the disease. [72] For the survivors, life changed dramatically. Weakened by disease, hunters lacked the strength to provide for the tired and dejected members of their villages. Starvation ensued. The demographics of small village settlement changed as orphaned children and others moved to neighboring villages. Often the Russian artels took in the orphaned children. [73] Entire villages disappeared as survivors fled to live in large villages. By one estimate, the Native population of the villages of Cook Inlet fell by fifty percent between 1836 and 1843. [74]

In the account by Zakahar Tchitchinoff, an employee of the Russian-American Company in the early 1800s, the epidemic of 1836 irrevocably devastated local villages and Native lifestyles on the Kenai Peninsula. The effects of the epidemic on the small, dispersed villages of the outer Kenai Coast can only be presumed through these accounts. Frequently visited for trade and hunting, these insular villages would have little protection against the effects of foreign disease.

...During the following winter (1836-37) I traveled continually from village to village in the Kenai District, trading, but it (sic) nearly every place the population had been reduced by at least one-half by the ravages of small pox. In many places the people were still of the opinion that the dreadful disease had been sent among them by the Russians, but a few individuals who had an opportunity to observe the effects of vaccination in Kadiak were of great service to us in assisting to eradicate the prejudice from the minds of the people. Some of the villages presented a terrible spectacle, the well inhabitants all having fled to some other locality while the helpless sick and the dead alone occupied the place–the latter in various stages of decomposition. During the cold weather, the epidemic abated somewhat in violence, but in the spring of 1837 it broke out again as bad as ever. [75]

It is possible that the outer coast villages never recovered from the devastating effects of the epidemics. Some villages were known to exist into the 1880s, but the decreased numbers may have contributed to the eventual relocation and loss of these villages. However, Russian recognition of a continued Native presence and of tribal organization is substantiated by inclusion of the Chugach in the Charter of 1844 that placed Natives under the colonial administration. The charter pertained to settled tribes, including "tribes living on the American coast, such as Kenais, Chugach and others." [76] Doroshin, a Russian mining engineer and geologist who spent several years in the Kenai region, was aware of five Chugach villages in 1852. Doroshin calculated a combined population of 284 persons. These villages fell under the jurisdiction of the Constantine Redoubt on Hinchinbrook Island. Doroshin also noted two additional villages, "Alexandrovskoe and Akhmilinskoe" on the southeastern shore of the Kenai Peninsula. [77] Akhmilinskoe had a population of ten families. In 1860 Golovin determined the Chugach population to be 226 males and 230 females, a total of 456. These estimates were based on the number of people living in the vicinity of the Constantine Redoubt. [78]

Living on the outer coast was difficult for the Chugach and Russians alike. With major Russian settlements to the east and west of the coast, the Native population was torn between the demands of working for the company and sustaining year round villages. This uneasy relationship lasted until the Russians moved farther south to establish a government seat in Sitka. However, the villages never regained the population they once had. Coastal inlets that may have once supported viable villages became stopover points for small boats navigating between Nuchek to the east and English Bay and Kenai to the west.

|

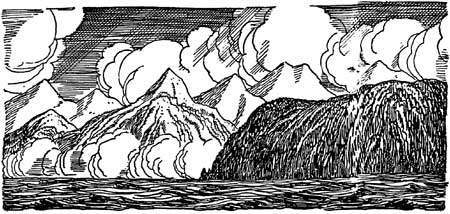

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, A Journal of Quient Adventure in Alaska, 1920. The Rockwell Kent. Legacies. |

kefj/hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002