|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 3:

EUROPEAN EXPLORATION AND RUSSIAN SETTLEMENT PATTERNS ON THE LOWER KENAI PENINSULA

Investigate possible resources, make necessary descriptions and then continue the journey as long as summer makes it possible.... — Grigorii Shelikhov, 1785

|

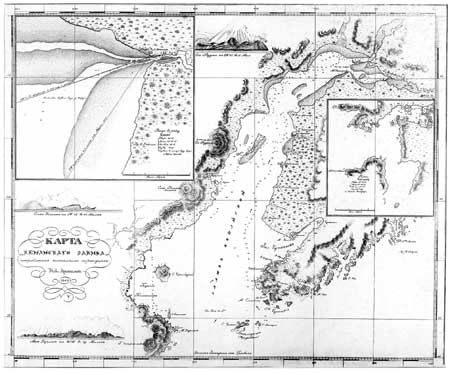

| Map 3-1. Historic Sites-European Exploration/Russian Settlement. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In the late 1700s Russian and European interests centered on southcentral Alaska. During this period, outside adventurers pursued economic opportunities on Kodiak Island, Cook Inlet, and Prince William Sound. These regions had comparatively warm microclimates, ice free protected bays, accessible forests, and pasture lands suitable for hunting and agriculture. For the most part, however, they avoided Kenai Peninsula's seaward coast. Tidewater glaciers at the mouths of deep fjords alternating with narrow jetties of rocky mountainous outcrop, as is found along the Kenai Peninsula, had few redeeming features for the development of permanent harbors, trading posts, or settlement. Fort Voskresenskii, the Russian fortified redoubt and shipyard constructed on the lowlands at the head of Resurrection Bay in 1794, [1] was abandoned after the construction of only one vessel. In the early 1800s the Russians relocated their shipbuilding industry to Kodiak and Sitka. By 1820 the Russians had begun to remove Fort Voskresenskii. As Russian investment eventually moved into other regions of Alaska, there appears to have been little regret at leaving the Kenai coast.

European Exploration and Trade on the Kenai

Peninsula

By the late 1700s, European interest and trade in southcentral Alaska increased despite Russian settlement and enterprise (see Table 3-1). Surely attracted by Russian commitment to the area's resources, English and Spanish ships entered southcentral waters in search of new routes, fame, and trade. In 1778 Captain James Cook ranked among the most noted of these first explorers. [2]

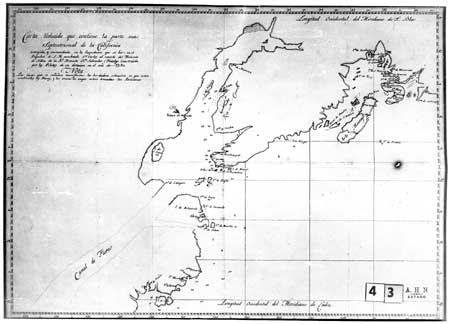

When Cook returned to England in 1780, his lucrative trade in Alaska sea otter pelts received no public attention. Mindful that the price sea otter fur brought on the Chinese market would only heighten European rivalry, Britain, then at war with the American Colonies, hoped to keep the news secret until it could afford to monopolize the fur trade. Spain, in turn, attempted to employ a similar tactic of concealment in their land claims north of California. Spain withheld official published accounts of its three expeditions in the 1770s, a move that later undermined the Spanish claims of exclusivity. [3]

The English, who protested the Spanish claims, argued that Native habitation pre-dated Spanish exploration and that the Spanish had made little attempt to establish any type of permanent settlement. [4] According to the accounts of the Russian sponsored expedition of Joseph Billings in 1790, Spanish frigates annually visited villages and forts in the vicinity of Cook Inlet trading hardware, beads, and linens for sea otter pelts. [5] Otherwise, most of the Spanish exploration originating from forts in California ventured only as far northwest as Prince William Sound (see Table 3-1).

|

| Spanish Map of Cook Inlet and Kenai Coast Region, 1790. Archivo-Historico Nacional. Library of Congress. |

Table 3-1. Chronological Summary of Russian, Spanish, and English Exploration and Survey of the Kenai Coast and Prince William Sound Regions

| 1741 | Alexsei Chirikov on board the Sv. Pavel, and Vitus Bering in the Sv. Petr, set out on the Second Kamchatka Voyage and the Great Northern Expedition. In August, Chirikov sited the Kenai Peninsula and Kodiak and Afognak islands. | ||

| 1778 | In May 1778 James Cook arrived in Sandwich Sound [Prince William Sound] and then sailed west along the Kenai Peninsula to Cook Inlet. Cook surveyed the inlet in hopes of finding a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. | ||

| |||

| 1779 | The third Spanish expedition set sail to the Northwest under the command of Naval Lieutenant Ignacio de Arteaga with F. Quiros y Miranda of the royal armada. Arteaga performed ceremonies at Port of Santiago on Hinchinbrook Island and at the entrance to Cook Inlet to claim land for Spain. The expedition traded with the Chugach. | ||

| 1781 | Evstratii Delarov, Dmitrii Polutov, and Potap Zaikov explored Prince William Sound. Russia looked to expand fur outposts and hunting expeditions to the Alaska mainland as Aleutian fur resources disappeared. Navigator Stepan Zaikov visited Prince William Sound in the vessel Aleksandr Nevskii, belonging to the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company. | ||

| 1783 | Filipp Mukhoplev and Potap Zaikov sailed to Prince William Sound from a trading station on Umnak Island. They remained until 1784 despite attacks from the Chugach. | ||

| 1785 | Grigorii Shelikhov sent a crew of fifty-two Russians and 121 Aleuts and Koniags to Kenai and Prince William Sound on a reconnaissance to "investigate possible resources, make necessary descriptions and then to continue the journey as long as summer makes it possible." | ||

| 1786 | James Strange, joined by William Tipping, anchored in Prince William Sound in search of furs to market in Canton, China. Tipping's ship, the Sea Otter, last seen in Prince William Sound, was lost at sea or attacked and destroyed. | ||

| 1786 | John Meares sailed to Chugach Bay from Kodiak via Cook Inlet in the Nootka and wintered in Snug Harbor Cove. | ||

| 1786-7 | Nathaniel Portlock and George Dixon traded with Natives at Port Graham and explored Prince William Sound in the ships King George and Queen Charlotte. Portlock and Dixon had visited the coast eight years earlier as mates on Cook's expedition. | ||

| 1788 | Captain Esteban José Martínez in the ship Princesa claimed Montague Island in Prince William Sound for Spain, as Russian and English exploration encroached on Spanish claims in the Pacific Northwest. Under orders from Shelikhov, Evstratii Delarov instructed Gerasim Izmailov and Dimitrii Ivanovich Bocharov to explore Prince William Sound in the ship Three Saints. The navigators surveyed the coast as far south as Lituya Bay, placing plaques and crests at several locations to establish Russian territory. | ||

| 1789 | Gerasim Izmailov surveyed the southeastern coast of the Kenai Peninsula after a voyage to Lituya Bay. | ||

| 1790 | Captains Joseph Billings and Gavriil Sarychev sailed along the southeast coast of Kenai Peninsula on an expedition to assess Russia's possessions. At Nuka Bay they encountered two Natives in a baidar. The ship attempted to enter the bay, but was forced to return to open waters before siting a village. Spanish sea captain Salvador Fidalgo sailed north from Mexico trading for sea otter pelts. He anchored in Prince William Sound and at Port Graham. Fidalgo encountered Russians at Port Graham and later on Kodiak Island. | ||

| 1791 | Alejandro Malaspina and José Bustamente y Guerra visited Prince William Sound on an around-the-world voyage of exploration. | ||

| 1791 | Lebedev-Lastochkin Company seized control of Shelikhov posts at Kenai on Cook Inlet and in Kachemak Bay. | ||

| 1792 | Hugh Moore repaired the British East India Company ship the Phoenix (namesake of the Russian-American Company Phoenix) in Prince William Sound where he met Aleksandr Baranov. | ||

| 1792-9 | Orekhof Company in operation. Named for a Russian trader in Prince William Sound, the company was a rival of both Shelikhov and Pavel Lebedev. | ||

| 1793 | Lebedev-Lastochkin Company established first trading post in Prince William Sound. It was Fort Constantine, at Nuchek on Hinchinbrook Island. | ||

| 1794 | George Vancouver as commander of the Discovery, surveyed Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound en route to Nookta Sound. He had first sailed to Alaska in 1772-1780, with Cook on his second and third voyages. | ||

| 1797 | James Shields, first commander of the Phoenix, mapped ship routes along the American coast, 1793-1797, and described Resurrection Bay. | ||

| 1804 | A navigator named Bubnov thoroughly surveyed the eastern coast of Kenai Peninsula to Prince William Sound. | ||

| 1849 | Russian Governor Mikhail Dmitrievich Teben'kov commissioned Illarion Arkhimandritov to survey and map Cook Inlet, the eastern peninsula coastline, and Prince William Sound. | ||

This list is meant to be representative, not conclusive. American exploration and trade are entirely omitted. Also, descriptions of trade and travel along the coast continued after 1849.

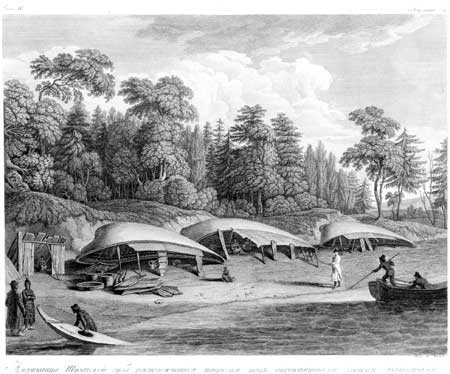

Soon after the 1783 Treaty of Paris, British trade routes developed between the northwest American coast and Canton, the only Chinese port open to international vessels. The first expedition of King George's Sound Company, also known as the London Company, navigated along the southeastern shore of the Kenai Peninsula. [6] In July 1786, company representatives Nathaniel Portlock and George Dixon left Cook Inlet, crossed Kachemak Bay and entered the narrow harbor of Port Graham. In search of a route to the Pacific, the captains assumed the harbor was an inland channel and named the small island at the entrance Passage Island. According to Portlock, Russian occupation at Port Graham appeared to be a seasonal and temporary encampment manned by twenty-five Russians and a crew of Natives from Unalaska and Kodiak islands. The Russians slept in a canvas tent while the Native crew took shelter under overturned boats pulled up on shore. There were no signs of trade with local Chugach, and Russian hunters depended on their crews to trap and hunt furs. While scouting the inner shores of the harbor, Portlock and Dixon observed several large Native huts that appeared to be recently abandoned. On the northern shores of the harbor they recorded the location of two veins of coal on the surface of the rocky hillside. Portlock wrote:

We landed on the west side of the bay, and in walking around it discovered two veins of kennel coal situated near some hills just above the beach, about the middle of the bay, and with very little trouble several pieces were got out of the bank nearly as large as a man's head.... In the evening we returned on board and I tried some of the coal we had discovered and found it to burn clean and well. [7]

|

| Overturned boats typically served as shelters. Bancroft Library. |

In 1788 the British sea captain John Meares collaborated in a joint trading venture known interchangeably as the Associated Merchants of London and India, the United Company of British Merchants, and the South Sea Company of London. The company concentrated its trading efforts between the Queen Charlotte Islands and Prince William Sound. In 1789, Captain William Douglas received orders to trade as far as the Sound, then to turn back. The land to the west of the Sound, including Kenai Peninsula and Cook Inlet, had less potential as trading zones as "it is so totally possessed by Russians that proceeding there would be only [a] waste of the most valuable time." [8]

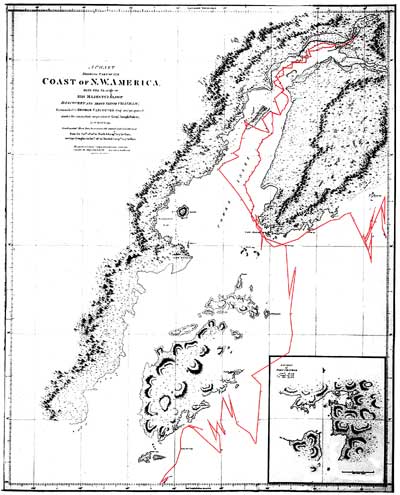

In 1790 British naval officer George Vancouver commanded his ships the Discovery and Chatham to the Pacific Northwest to reconcile British interests at Nookta. Four years later, Vancouver arrived in Alaska from Hawaii and surveyed the waters of Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound. Russian contacts in Cook Inlet led Vancouver to believe that he could bypass the Pacific coast of the Kenai Peninsula through an inland waterway at the head of Turnagain Arm. This waterway supposedly led to the Passage Canal in Prince William Sound. Learning that the waterway did not exist, Vancouver circled the outer peninsula and dismissed a survey of the coast as too time consuming. He preferred to "examine the shores of the peninsula, so far only as could be done from the ship in passing along its coast." [9] Vancouver noted the abrupt mountainous shoreline and long valleys "buried in ice and snow, within in a few yards of the wash of the sea; whilst here and there some of the loftiest of the pine trees just ‘shewd' their heads through the frigid surface." [10] From the maps of his ship route, he obviously steered clear of the bays and rocky outcrops along the Kenai coast. He recorded the Pye and Chiswell islands. He described the Chiswells as a "group of naked rugged rocks, seemingly destitute of soil, and any kind of vegetation." [11] Eighty years later, George Davidson proposed that Vancouver mistook the Chiswells for several "islets and the broken and numerous points of the long, low, wooded promontories stretching southward and forming Ayalik [sic] Bay, off which lie the Chiswell Islands." [12]

|

| Tracing of Vancouver's route (in red highlight) around the Kenai Peninsula. Alaska State Library, photo PCA 62-126. |

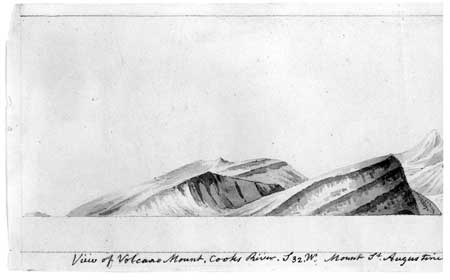

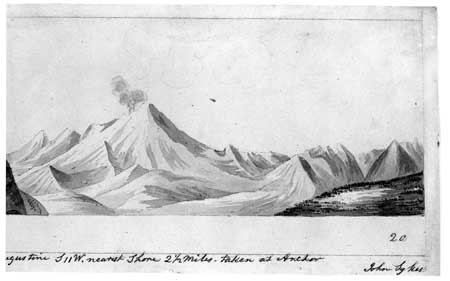

Thomas Heddington, a midshipman on the Chatham and the youngest member of the expedition, was one of three illustrators on Vancouver's voyage. [13] The two others were Henry Humphreys and John Sykes. Heddington prepared several surveys and drawings of the coast between Cape Elizabeth and Prince William Sound. Once back in London, Heddington submitted his work to the Hydrographic Office, but later in 1808 requested that his work be returned. The Admiralty honored the request only to lose all record or trace of the drawings. [14] One, entitled The Coast from Cape Elizabeth to the Western Entrance of Prince Williams Sound- with Elizabeth Island, Pyes Islands and Chiswells Islands off the Coast, would have been among the earliest known renderings of the coast. [15]

|

| Etching of Cook Inlet and environs, by John Sykes, Bancroft Library. Etching style similar to views that Humphreys produced of Outer Kenai Coast. |

|

| Etching of Cook Inlet and environs, by John Sykes, Bancroft Library. Etching style similar to views that Humphreys produced of Outer Kenai Coast. |

At Port Dick, a deep bay at the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula, Vancouver encountered a large party of Natives in two-man boats. The men approached the English ships with a willingness to trade. Their number impressed Vancouver; he estimated a party of over four hundred men. Archibald Menzies, the botanist on board, described the men as being of "low stature, but thick and stout made with fat broad visages and straight black hair ... and their canoes are equally neat having their seams sown so tight as not to admit any water...". [16] In the 1930s, anthropologist Frederica de Laguna explained this encounter as one of the large inter-regional sea otter hunting expeditions that traveled along the coast. [17] Aleksandr Baranov, in a letter to Grigorii Shelikhov, recounted that Vancouver met a 500-baidarka hunting fleet of Kodiak and Chugach Natives led by Russians from the Kenai and Resurrection Bay areas in April and later again in Yakutat Bay. [18] The fleet stopped at the shipyard in Resurrection Bay to pick up five Russians, including G. Prianishnikov and Konstantin Galaktionov, and arrange for repairs and supplies of cannons, guns, and ammunition for the trip south to Icy Bay. [19]

Henry Humphreys prepared a sketch of the Port Dick encounter. In the margin of the drawing, Humphreys penciled in explanatory notes to the engraver back in England. He directed the engraver to add to the image "many canoes ... going into the Creek [sic] each carrying 2 people ... sight. Indian holding up Skins for traffic ... some going in at that place." [20] The final drawing, unlike Humphreys's original, shows the bay full of Native vessels.

Vancouver had anticipated a layover at the Russian shipyard in Resurrection Bay, but stormy seas and fog set in west of the Chiswell Islands. Apprehensive of the rocky coast and lacking accurate charts, Vancouver cancelled the stop and sailed the Discovery past Port Andrews (Blying Sound) into Prince William Sound. The route and the weather probably accounted for the poor delineation of the bay and coast in his atlas. However, his route as traced on his maps shows the wide clearance he gave to the coastline.

Russian Enterprise on the Outer Kenai Coast

By 1786, Russian hunting parties had clearly decimated sea otter populations in Cook Inlet, forcing Native hunters to enter Chugach territory in Prince William Sound and push farther south toward Yakutat. Official estimates calculated a take of 3,340 pelts a year between 1743 and 1799. [21] Desperate to find new fur resources, the Russian began a series of scouting expeditions in Prince William Sound. Evstratii Delarov, Dimitrii Polutov, and Potap Zaikov, who apparently had seen the Sound on a map drawn by Cook, sailed from the Aleutians, past the outer Kenai Coast, to Kayak Island in Prince William Sound (see Table 3-1). The traders alienated and brutalized Natives in the region, a move that resulted in retaliatory attacks by both Kenaitze and Chugach. The Russians spent the winter on Montague Island at Zaikof Bay and almost half the crew died of scurvy. [22]

Two years later Gerasim Izmailov and Dimitrii I. Bocharov, under instruction from Grigorii Shelikhov, returned to Montague Island. They noted abandoned Native houses and wrote, "the inhabitants of this point were the last of the Oogalakhmutes who lived here in constant war and hostilities with the Kolash [Tlingit]." [23] At Montague Island, the closest island in the Sound to the Kenai Peninsula, the traders met Natives in two-hatch baidarkas willing to trade. Izmailov followed the men to a grouping of Chugach dwellings on the shores of a "sheltered channel formed by the island Khligakhlik [Latouche] on the right and the mainland on the left." [24] Here he observed village houses from the boat, but never went ashore.

Accounts by Sarychev and naturalist Carl Merck, of Captain Joseph Billings's "Northeast Secret Geographical and Astronomical Expedition," tell of a meeting with a group of Natives near Nuka Island in 1790. In early July, Billings's ship left Kodiak and headed for Cook Inlet. Forced to turn eastward in the prevailing winds, the ship rounded the peninsula. After four days of mist and fog, the crew caught its first glimpse of the outer Kenai coast and the channel of Nuka Bay. Two Chugach spied the ship and set off from the shore in a baidar to welcome the ship. They offered gifts of a river otter, sea otter, seal, and petrel. [25]

The following excerpt recounts Sarychev's version of the chance meeting and his unsuccessful attempt to follow the Chugach into the bay.

From these Americans, we learned that the bay ahead of us was called Nuka, and the cape that presented itself on its eastern side, belonged to an island, which was separated from the main land only by a strait. They added, moreover, that in this bay were several [more] of an inferior size, with sandy bottoms, which furnished good stations for shipping. Their habitations lay in one of the havens, to which they invited us with much cordiality. Captain Billings ordered the ship to tack, and put into the bay, after which we bore up to the island in question, passing a rock to the left that was about two miles distant from it. On arriving at the bay, Captain Billings found it most prudent not to advance. We accordingly tacked about again, and soon gained the open sea. [26]

|

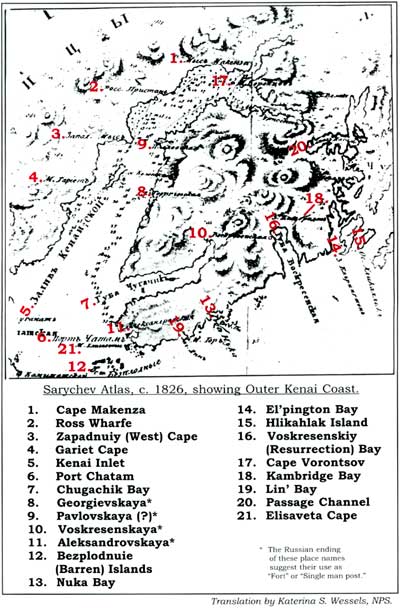

| Sarychev Atlas, c. 1826, showing Outer Kenai Coast. Translation by Katerina S. Wessels, NPS. |

Martin Sauer, Billings's secretary on the expedition, recorded an exchange at the mouth of Cook Inlet with a Spanish frigate and later with several Natives off the coast of Cape Elizabeth. The Natives freely traded pelts for beads and tobacco, then returned to the coast with one of the crew. Sauer noted that the Spaniards traded regularly in the region with both Natives and Russians and in part acted as middlemen to supply the Russians with pelts in return for hardware, beads, and linens. [27]

Heavy rains and fog shadowed Billings's ship until it arrived near Montague Island. The only other observances that were made of the coast were references to its fine timber that reached the water's edge and to the deepness of the sea. [28]

Russian enterprise quickly followed these initial scouting trips. Russian traders established temporary posts and fortified redoubts at strategic hunting locations in the Gulf of Alaska. The Shelikhov-Golikov Company established Fort Alexandrovsk at English Bay near Cape Elizabeth in 1786. [29] Farther into Cook Inlet, the Pavel S. Lebedev-Lastochkin Company constructed Fort St. George on the Kasilof River in 1787 and Fort St. Nicholas on the Kenai River in 1791. The company relied heavily on a Kenaitze labor force to build these posts. In a concerted effort to control Native hunters and fur resources, the two companies monopolized territorial influence from Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island to Prince William Sound and Yakutat. However, in late 1791 open rivalry broke out between the two companies. In 1793, Baranov reported to Shelikhov that he would build a fort complete with barracks, blacksmith, and warehouse at the head of Resurrection Bay to block any move by the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company.

In 1792, Baranov first visited the Chugach region. Driven by the constant need to replenish falling pelt stocks and his own desire to expand Russian holdings and succeed as a manager, Baranov wanted to establish a fortified station in Prince William Sound. Traveling in a skinboat, Baranov set out to approach the Chugach in the vicinity of Montague Island.

Baranov described the Chugach as both warlike and savage, but ever frightful of the sight of the Russians and more likely to hide than attack. [30] The Russian naval officer Davydov recounted Baranov's expedition and his meeting with the Chugach.

When they learnt that Baranov was travelling to Chugatsk Bay they disappeared from their settlements so that none of them was visible anywhere. All that could be seen everywhere were poles with sticks bound to them at right angles. The Russians believed that these sticks indicated the direction of the fleeing villagers had gone - and that they were left as a sign for their comrades who might have been caught out of the village or unawares and would not know what had happened. [31]

In anticipation of an attack by the Tlingit against his men, Baranov traveled in the company of the Chugach and often took hostages. Despite these precautions, his crew fell victim to a Tlingit raiding party while camping on Montague Island. The party consisted of Ugaliagmiuts from Cape St. Elias [on Kayak Island] who in the night mistook the Russian camp for one of the enemy Chugach. Twelve men died in the retaliatory raid. [32] According to one account, the attackers intended to continue raids along the Chugach coast and then proceed to Cook Inlet. [33]

Fort Voskresenskii and the Building of the Phoenix

After Baranov's initial expedition, he freely navigated the bays of the outer Kenai coast including Resurrection Bay and Prince William Sound. He possessed sufficient knowledge of the area to choose a site in Resurrection Bay for the construction of a fort and shipyard. The Russian name Voskresenskaia gaven' or guba, chosen by Baranov in 1792, was the literal translation of Resurrection Harbor or Sunday Harbor. Traveling by the bay in early spring close to the date of Easter Sunday on the Julian Calender, Baranov celebrated that visit with the joyous name. Resurrection Bay replaced the earlier Russian name for the bay, Delarov Harbor; in the 1770s, Portlock had named the area south of the bay as Port Andrews, and the name Blying Sound also denoted the waters at the mouth of the bay in the Gulf of Alaska.

Like most Russian settlements, Fort Voskresenskii was built on the coast. Proximity to the sea allowed for the easy transfer of stockpiled furs from warehouse to ship. Native trade as well as access to coastal hunting grounds mandated the use of ships and smaller skin boats. As resource needs changed, the Russians eventually dismantled some of their coastal forts. As one researcher observed, "...each of the abandoned [Russian] sites was in a location of little value to later white settlement." [34]

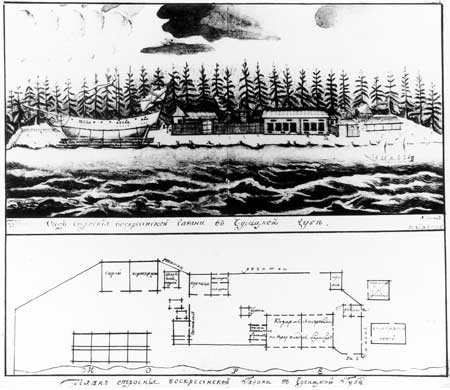

Completed in 1793, Fort Voskresenskii incorporated many military features. A large rectangular stockade constructed of vertical logs encircled interior buildings similar to the design of Siberian forts. Many buildings were braced directly into the stockade. Two watchtowers provided high sentinel posts. Men lived in a large central building that faced the bay complete with a storage area and cellar. In the event of an attack, the crew could draw wooden shutters to seal off the windows. Located outside the principal stockade, the shipyard was protected with chevaux-de-frise, a tight wooden barricade made of sharpened posts. [35]

With the fort under construction, Baranov turned his interests to the shipyard. Baranov shared Shelikhov's long-term aspirations for a colony-based fleet of ships. With a supply of trading vessels on hand, Baranov hoped to open Japanese trade routes and to expand the international market for goods from the colony. Shelikhov envisioned the construction of a large frigate, approximately 85 feet long, to transport pelts, supplies, news, and passengers between the Russian forts in America and Okhotsk in Siberia. [36] In 1790 Shelikhov informed Delarov, then his chief manager, of the need for such a vessel and reassured him that necessary supplies would be forthcoming if he secured a carpenter from the Billings Expedition.

Baranov first learned of Shelikhov's shipbuilding plans in 1792 in a hand carried set of instructions from James Shields, a second lieutenant in the Russian Ekaterinburg regiment. [37] Shields, who was fluent in Russian, had been building a ship in Okhotsk for the Shelikhov Company. In 1792, Shields sailed the ship to Kodiak Island with a supply of rigging and hardware for the construction of a new frigate.

|

| Drawings by James Shields of Russian shipbuilding site in Resurrection Bay, c. 1795. University of Alaska, Fairbanks. |

While Baranov endorsed the shipbuilding plan, he lacked the essential materials to carry out Shelikhov's instructions. In one letter, Baranov openly balked at the scheme of a ship, proclaiming a hopelessly low inventory of laborers and supplies, among which there were no nails or caulking, only half a flask of pitch, and very little iron. [38] Most of the canvas was too worn and rotten or had been used to make tents and pants for Native hunters. [39]

Baranov's problems were not limited to poor supplies. Shelikhov agreed with Baranov that Resurrection Bay benefited from dramatic changes in tide and that it held promise as a place to launch, moor, and rig ships. As a construction site, however, it was too limited; Shelikhov instead encouraged Baranov to choose a site with more timber. Baranov assured Shelikhov that he had assessed the forested shores of Kodiak and Afognak islands and the Kenai Peninsula; he had settled on the Chugach region, in part, for its proximity to dense timber. He was convinced that local stands of larch trees on an island in Prince William Sound would supply the needed raw logs. He recounted that the ship could be built "very economically from larch trees called in English spruce, more durable and stronger than the wood at Okhotsk, and painted by a composition that I invented." [40] Larch was the wood of choice for the Russian ships built in the colonies and also for those built at Okhotsk. [41] Baranov avoided the use of fir, considering the planks too rigid and scarred with knots for shipbuilding. [42] Shelikhov encouraged Baranov to continue to survey the coast and forego plans for Fort Voskresenskii. To Shelikhov, shipping in logs in from Grekovskii ostrovok (Greek Island) [43] in Prince William Sound was too risky for a long-term ship building operation. As he informed Baranov, "I must conclude that your shipyard is not completely suitable, or that you have not yet had time to find a good location with all advantages." [44]

While Shelikhov continued to focus on the issue of timber, Baranov reminded him that proximity to Kenai and to nearby salmon streams was equally important. Also, as mentioned above, he needed to stop the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company from gaining control of the site.

They took the best places for getting food supplies, and made the inhabitants prisoners. I chose this bay in order to hinder their communication between Kinai and Chugach over the nearest neck of land.... If we move, only the labor spent building the fort will be wasted; in the meantime, our artel is in a place of refuge for the Chugach from the Lebedev men and a barrier for their communication. The Kinai people want to move here to get away from Lebedev's men and are waiting only the permission from me and from Father Archimandrite [Ioasaf]. [45]

Baranov insisted that these strategic concerns outweighed the lack of timber and isolation.

Over the next year, Baranov transported approximately one-fifth of the logs on the company ship Orel. Supply shortages continued, along with the threat of attack from both Natives and Lebedev-Lastochkin men. (Natives easily outnumbered the Russian construction crews at both Voskresenskii and Kenai.) To improve relations with the Natives, Baranov traded extensively with the Kenai and Chugach to procure both furs and food. To keep a steady supply of food and furs on hand, Baranov used beads to conduct local business and maintain an appealing collection:

As you know, we have no trading goods here, only beads and even they are of the small size. The large beads are of the kinds for which there is no demand. There are not enough to buy sea otters with, and even our native workers no longer take them in exchange for fox skins. [46]

Baranov's need to meet company expectations at whatever cost discouraged his crew. The prospect of living and working more than 260 miles from the familiarity of Kodiak scared Baranov's hired crew. To procure laborers, Baranov enlisted more than half of his 152 men, leaving the rest on Kodiak. [47] Refusing to pay them full wages until they arrived in Resurrection Bay, Baranov managed to lure his reluctant crew to the remote site.

Had I paid the men on Kadiak Island first I would not have been able to force them to go to Chugach Bay. The men who are free would have quit and the men who are in debt would either have refused to go or would have started a mutiny. [48]

Laborers working for the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company menaced the shipwrights, scaring them with threats of hunger if they ventured into Resurrection Bay. [49] They also harassed and stalked Baranov's men who felled trees on Hinchinbrook Island. Forced to contend with repeated attacks and threats against his men, Baranov finally managed to convince many of Lebedev-Lastochkin's employees to change sides and join his crews. [50]

Morale remained low and during the winter of 1793-94, Baranov's crew made an attempt to kill their supervisor. [51] Unhappy with the daily ration of iukola or dried salmon, the crew demanded an allotment of two pounds of flour. Petty rivalry ensued. Communication deteriorated over the winter and fearing they had been forgotten, the men decided to retreat to Kodiak. Problems also escalated on Kodiak Island among the men scheduled to transfer to Resurrection Bay. Taking the threat on his life in stride, Baranov wrote to Shelikhov, "I straightened things out on my return, but the scoundrels made an attempt on my life. However, I will not speak of that. I would not deserve the position of manager if I could not stop troubles in my company." [52]

The use of Native labor supplemented Baranov's crew and fulfilled one of Shelikhov's earlier stipulations. Determined to train a skilled local labor force that could grow within the ranks of the company, Shelikhov had directed Baranov to assign young Chugach apprentices to work with ship artisans.

My only instruction is that you must not fail to have young American Natives study with master shipwrights, carpenters, blacksmiths, artisans and navigators. Generally speaking American Natives make very capable seafarers; all they need is practical experience, especially with the compass which is so necessary; then they can master this. [53]

Baranov began construction of the Phoenix in 1793 after completion of the fort barracks and a blacksmith shop. Already delayed by a year because of bad weather and the other problems discussed above, the building of the Phoenix proceeded throughout the winter of 1793 and was completed in September 1794.

Baranov likely modeled the ship after a schooner belonging to Hugh Moore. While sailing in the Chugach region in 1792, Baranov encountered the Irishman Moore en route from Bengal. Moore had anchored his ship, also named the Phoenix, in Prince William Sound to repair damage to the masts. [54] Baranov spent five days with Moore on his 75 foot, three-mast ship. This gave Baranov ample time to admire its design and construction.

Baranov's Phoenix measured 60 feet long at the keel and had two decks and three masts. It was 73 feet in length along the lower deck and 79 feet along the upper. The width of the ship was 23 feet, and at the upper deck the height reached 12-1/2 feet. The ship's total capacity was 180 tons. In Russian texts, the vessel was commonly referred to as a frigate. In an account by Natalia A. Shelikhov, Grigorii's wife, the Phoenix carried twenty-four guns. [55] When the finished ship set sail in 1795, it sported a variety of exterior finishes and colored sails.

Baranov's Phoenix was a patchwork of local technologies and materials. Iron, which was so critical to the construction, was in short supply. Iron was needed to manufacture an anchor, anchor chains, ring bolts, windlasses, nails and tools. Baranov estimated that he had received only 300 finished nails from Shelikhov, and more than 600 axes needed to be forged or repaired at the shipyard to fell trees. [56] At first, Baranov hoped to salvage enough iron from shipwrecks and second-hand sources. Discouraged by the poor quality and quantity of the metal, however, he decided to construct a local smelting plant. Turning to others for advice, Baranov consulted Father Juvenal only to realize that the priest's professed expertise with iron pertained to its chemistry and not to its smelting. [57] Relying on local sources of ore collected on the Kenai Peninsula, Baranov requested Shelikhov to send an expert in the field to establish a local factory. Baranov's blacksmith Tsypanov eventually forged his own items from metals that he found. [58]

Baranov, Shields, and his assistants, among them Vasilii G. Medvednikov, concocted a local paint and resin to protect and caulk the ship's hull. After a failed attempt at making turpentine, and having no tar, oakum, or pitch, Baranov sent 500 Native men, a number equal to one complete hunting party, to collect resin in the vicinity of Fort Kenai. The end product consisted of a paint-like substance made from the "entrails and offal of fish mixed with whale blubber." [59] Coated and caulked in stages, the vessel exhibited a variety of paint finishes. Bancroft reported that upon arriving in Okhotsk, the vessel underwent modifications, including the construction of upper decks. [60]

On 5 September 1795 the Phoenix, under the command of James Shields, left Resurrection Bay and sailed for Kodiak Island. For the ceremonial launching Shields made a sketch of the event and Baranov threw a party complete with homemade berry and root vodka. [61] Later that year, Gerasim Izmailov took charge of the ship for its first official voyage to Okhotsk. The Phoenix proudly carried in its hull a three-year backlog of furs. Baranov sent with Izmailov a plan of the Phoenix drawn by Shields. [62] He requested recognition and bonuses for the men who worked at Fort Voskresenskii.

On the Phoenix's return trip from Okhotsk, Baranov learned of Shelikhov's death. In 1795, Shelikhov's widow praised the ship in honor of her husband:

...Baranov, instructed by my husband, has experimented in shipbuilding. On this frigate he sailed to Kadiak and from there sent her to Okhotsk as I mentioned above with three years' accumulation of furs.... I have the honor of enclosing the plans of the above mentioned Resurrection Harbor where the frigate and these ships were built. In this manner shipbuilding was started even before the skilled workers arrived, justifying the labors and hopes of my deceased husband. [63]

The Phoenix, acclaimed as the first Russian ship built and launched in Alaska, made three round trip voyages between Kodiak and Okhotsk from 1795 to 1799, transporting passengers, furs, ammunition, and supplies. [64] On the second voyage in 1797-1798, Gavriil Talin piloted the Phoenix to Kodiak.

In 1799, on a return trip to Kodiak Island from Okhotsk, the Phoenix hit a May storm in the waters off the Aleutian Islands. All crew and cargo were lost. Within days, debris from the shipwreck began to wash on shore. Over the next year, objects continued to be found on beaches in the vicinity of the Gulf of Alaska. Davydov reported that "[f]lagons of vodka were discovered, bottles of sour wine, wax candles, a samovar, a ships's wheel, upper beams and other articles- in an area extending from Unalashka right down to Sitkha and even further south." [65]

Try as he might, Baranov never learned what happened to the Phoenix. In June 1800, he admitted that he still knew few details.

All this proves that a misfortune occurred. Probably our Phoenix, carrying the transport, was wrecked. We investigated on Shuiakh [Shuyak], Afognak, and the Peregrebnye [Wosnesenski] Islands and at Chugach from Nuchek to Kenai but no one there knew anything of a shipwreck.... The uncertainty troubles me. [66]

Eighty-eight crewmembers, including several major personalities in Russian America, lost their lives on the ill-fated voyage. James Shields, so instrumental in the construction of the ship, died as captain of the voyage. Archimandrite Ioasaf, the newly consecrated first bishop of America, Russian Orthodox Church dignitaries, Heiromonk Makarii, Heirodeacon Stephen, and a novice also perished. [67]

Many suspected that the Phoenix faltered off the Aleutians in the vicinity of Umnak Island. Speculation and hearsay surrounded the infamous shipwreck. Shields' inadequacies as ship captain came into question, suggesting that he lacked the experience to master the vessel in rough seas. [68] Others blamed the effects of a deadly outbreak of yellow fever that raged in Okhotsk and Kamchatka at the time that the Phoenix set sail. [69] Given the close quarters on board, the fever could have spread quickly — weakening the crew. Whatever the cause, the loss of the Phoenix put a temporary hold on local trade and business in the colonies. Baranov wrote of his predicament, lamenting the loss of trade goods needed to carry on local business.

It is a great misfortune for all of us, not to mention the loss of Company money and of private capital. What is most important, we will not have the supplies we need to keep on friendly terms with people here and to send out hunting and trading parties. [70]

Throughout the late 1790s and early 1800s, Baranov continued to sail between Kodiak and Prince William Sound with Fort Voskresenskii a regular port of call. At the same time, hunting crews frequently stopped at the fort en route to Nuchek. Transport of raw furs between the outer forts and the company warehouses in Kodiak kept up a steady stream of boat traffic along the coast. On one of these trips, in 1800, Baranov still had hopes of expanding and improving the settlement in Resurrection Bay. He had "the intention of visiting Voskresenskii redoubt to see the local Chugach and Kinai natives and to plan a new settlement there...." [71] However, the Russian-American Company had other plans.

Russian Interests Change along the Outer Kenai

Coast

In the early 1800s the Russians moved shipbuilding operations to Southeast Alaska, and Sitka became the Russian seat of governmental and economic activity. In 1818, Ludwig von Hagemeister replaced Baranov as chief manager of Russian affairs in the territory. The new manager brought new direction to the company and change to the outer Kenai coast.

One of Hagemeister's first acts was to consolidate the western forts. He sought to keep only those forts that had high economic potential and return. He did so because sea otter fur, the staple of Russian-American commerce, had virtually died out in the coastal waters of the Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound. Even by the early 1800s, Davydov had already noted a dependence on bear and black otter pelts at forts St. Nicholas and Alexandrovsk. After 1817 the Russian population had decreased on Kodiak Island, and Baranov ordered the move of property from economically stagnant Fort Aleksandrovskii on the end of Kenai Peninsula to a new location at Iliamna (now called Old Iliamna). [72] The new fort, which assumed the same name, was eventually built at Nushagak.

The decision to reevaluate and consolidate Russian forts coincided with international events that put the Russian government on the defensive against foreign interests in the colonies. [73] Vasilii Golovnin, convinced that American interests sought to overpower the Russian colonies and challenge the renewal of the Russian-American Company contract in 1819, advised the government to isolate and close the territory to all outside trade. [74] As a result, in the 1820s and 1830s the Russian-American Company diversified its economy to include agriculture, timber, and fish; it also moved to seek out markets in need of these commodities. The Russian government redirected expansion within the territory to the north, a move that realigned the coastal forts. In a parallel attempt to develop and populate portions of the territory that were deemed more profitable, former Russian-American Company employees received encouragement to initiate agricultural settlements. [75] This naturally attracted people to the more temperate regions and away from forts developed solely for hunting, shipbuilding, and fur trading. Some villages on the Cook Inlet side of the Kenai Peninsula, including Seldovia, were established as a result of this initiative.

The Russian reorganization overlapped with an overt move to reduce the number of Native villages. Arvid A. Etholen, governor of Russian America between 1840 and 1845, effected minor reforms in the behavior of Russian employees towards Alaska Natives. Looking to improve services to villages and in order to improve the condition of village life, Etholen directed the merging of villages on Kodiak Island from seventy-five to a mere seven. [76] Although the direct impacts of this decision cannot be assessed on the outer Kenai coast, the implications of this radical reduction were sure have affected neighboring areas.

In 1819, Hagemeister ordered the removal of the artel at Resurrection Bay and a consolation of materials and employees. His instructions also specified the need to move the entire settlement surrounding the fort, including the Native crew and their families.

Transfer the Russians and Kaiurs [Native workers] to Iliamna. As there remain but a few aboriginal inhabitants, try to persuade them to move to another more populous place, and it would be best if they were agreeable to moving to Iliamna. [77]

However, many sources indicated that although the Russians had every intention of moving the entire fort, it may have remained partially intact with only parts of it salvaged for iron and other scarce materials. In 1818, Golovnin described the site as a small fort in which "the Company maintains task forces of promyshlenniks or artels for trading with the natives who trade various furs for needed European goods." [78] Lieutenant Captain Pavel Golovin reported that by 1819 Fort Voskresenskii, along with neighboring Forts Alexandrovsk and Gerogevski, were odinochka or "single man" isolated camps or outposts. [79] In 1821, K. T. Khlebnikov described the fort as nothing more than a small building with one resident Russian and some horned cattle. [80] Sarychev's 1826 Atlas identified the fort as a single man outpost. [81] However, Tikhmenev reported that between the 1840s and the 1860s Fort Voskresenskii was "abolished." These varied accounts make it difficult to determine an exact date when the fort closed. There may have been an initial move in the 1820s with a smaller station left in place until the mid-nineteenth century as Tikhmenev implied.

Despite the relocation of Fort Voskresenskii, a Russian presence continued on the outer coast. Mikhail Teben'kov, chief manager of the Russian American Company between 1845 and 1850, conducted a major survey of the Alaska coast, the results of which were published in the 1852 Atlas of the Northwest Coasts of America. He assigned the Russian skipper Illarion Arkhimandritov the task of surveying the outer Kenai coast. He referred to several earlier surveys of the coast implying Russian interest and familiarity with this area, though many were lost or unavailable at the time that Teben'kov compiled the Atlas. Those who had surveyed Resurrection Bay probably included Captain James Shields (1793-94) and Danilo Kalinin (1806), the latter an employee of the Russian-American Company. [82] In 1804 a Russian navigator named Bubnov conducted a thorough summary of the coast. [83] However, all these surveys, like the English and Spanish maps of the region, were conducted exclusively from the sea with no detailed land descriptions. [84]

|

| Teben'kov Chart #5 showing Outer Kenai Coast, 1849. Library of Congress. |

In 1849, Arkhimandritov mapped the outer Kenai coast, Kodiak, Cook Inlet, and Prince William Sound. His skillful calculations formed the basis for most of the information on Teben'kov's maps of the region. [85] Davidson later relied heavily on Arkhimandritov's work on the seaward side of the peninsula. Vancouver had made no record the Kenai Coast. [86] Teben'kov deduced from Arkhimandritov's findings that the coast had few redeeming features.

It can be seen from his description that it is all uninhabited space, consisting of bays and straits, hardly convenient because at the very shore the depth is 30 to 50 sazhens [210 to 350 feet]. [87] The shore is mountainous, steep and rocky, covered with forests; the gorges and eroded mountains in many places are occupied by glaciers, crossing even into Kenai Bay. The well-known Voskresenskii Bay ... is equally inconvenient. It is has the same severity of climate, wildness of nature and inaccessible bottom. [88]

Aleksandr Kashevarov, described by Teben'kov as a hired skipper, was an experienced navigator in Russian America in the 1830s. He may have accompanied Arkhimandritov or worked independently on yet another coastal survey.

One of Teben'kov's motivations in mapping the coast was the anticipation of the increased presence of Russian whaling fleets in the region. He maintained that whaling ship captains needed precise charts and current surveys to locate safe harbors, both for protection and as layover stations during storms and periods of foggy weather.

Russian whaling operations in the Gulf of Alaska developed in response to an inundation of American whaling ships in the late 1840s. Encouraged by the discovery of coast-right whales and by the high price of sperm and whale oil, American ships dominated the market and pushed the whaling grounds all the way to the Sea of Okhotsk and the coast of Kamchatka. [89] Obviously intimidated and unable to stop the number of foreign ships, the Russian government formed its own fleet. In 1849 the Russian-American Company obtained permission to enter the fishery and instituted its own subsidiary, the Russo-Finland Whaling Company. [90] No match for the American fleet, the Russian company operated only from 1851 to 1854.

Equally interested in the territory's gold deposits, Teben'kov hired Petr Doroshin in 1847 to conduct a five-year survey of mineral resources in the southcentral region. Doroshin was a geologist, a graduate of the Imperial Mining School in St. Petersburg, and a member of the Russian Corps of Mining Engineers. Forced to abandon an investigation of Sitka, Doroshin traveled up the coast to Nuchek and then into Cook Inlet, stopping temporarily to explore gold traces. [91] Returning to the region in 1848 to follow up on his initial finds, Doroshin and his crew stopped at Nuchek and Resurrection Bay in between trips to the interior of the peninsula. [92] He recounted that:

... I left Sitka on the first of May and returned on the 4th of October. During this period the laborers under my command were at work only forty nine days, the remainder of the time being spent in excursions to Nuchek ... and Voskressensky Bay.... [93]

Noting the terrain between Resurrection Bay and the end of the Kenai Peninsula, Doroshin knew that the rugged glaciated coast he had observed and described in Prince William Sound continued. Yet, from his writings it seemed his ship kept a safe distance from the coast. "Between Resurrection Bay and the Peregrehni [Wosnesenski] Islands," he noted, "there are many glaciers but from the sea I could see only three of them." [94]

Working within strict time and weather constraints, Doroshin was unable to locate enough gold to satisfy Russian officials. Directed to turn his attention to coal, Doroshin provided the first reports on deposits at Port Graham as well as Kachemak Bay in the early 1850s. [95] His survey included the eastern end of the peninsula, but stopped before reaching the southeastern coastline. In 1853 he returned to Russia; in 1866, he published notes on his Alaska experience and gold discoveries in a series of articles for the Russian Mining Journal.

The Kenai Russian Orthodox Mission

The establishment of a Russian Orthodox mission in Kenai included in its district villages along the outer Kenai Coast and Prince William Sound as well as part of the Alaska Peninsula. Originally part of the Kodiak Mission, the Kenai Mission was founded in 1844. The mission served 150 miles of coastline; the villages of English Bay, Seldovia, and Nuchek were the closest to the outer Kenai coast. Bishop Innokenty, in 1842, noted that:

In accordance with article 11 of the Ukase of the Holy Synod of January 10, 1841, I intend to separate several villages and settlements from the Kodiak parish, to organize a new mission at Kenai Bay at the first opportunity and to use all means available for the accomplishment of this plan as soon as possible. [96]

Golovin observed that in 1846, 133 women and 178 men joined the Kenai Mission. [97]

The church formed the new mission to enable priests to travel to outlying villages; under the old arrangement, trips from Kodiak to the Kenai Peninsula proved increasingly treacherous as priests tried to reach as many villages as possible. As was customary, Russian priests regularly traveled in open skinboats accompanied by a song leader and other lay clergy. In 1856 Abbot [Father] Igumen Nicholas, the priest in residence at Kenai from 1845 to 1867, reported that the during one of the trips to the Chugach villages and to Nuchek Redoubt ‘to fulfill the needs of the church for the benefit of all the Christians living here,' the baidarkas overturned and all the supplies were lost. [98] It may have been several years before Abbot Nicholas returned to Nuchek with new supplies.

Although it is known that Russian priests frequently traveled between the chapels and forts at Alexandrovsk and Nuchek, it is not known how extensively they documented visits to smaller villages along the coast. Kenai, a prominent settlement in Russian America, provided a center for the mission documents and records pertaining to the church and its domain. However, a review of a portion of Russian Orthodox Church records from the period provided limited descriptions of Native villages along the outer coast. [99] Most of the larger villages later had small chapels and lay readers of their own to administer services. Trips to villages occurred on a rotating basis; the Kenai mission's lone priest traveled to opposite corners of the mission in alternate years.

Traveling Russian Orthodox priests arrived in villages prepared to perform baptisms, marriages, and often to intervene as a third party mediator in local domestic and business disputes. Church services consumed the majority of time. Acting on behalf of the Russian-American Company and other local interests, priests also assumed the responsibility of village doctor administering vaccinations as a precaution against future epidemics. [100]

Between 1858 and 1860 Abbot Nicholas visited Akhmylik, a Chugach village located between Seldovia and Nuchek. [101] Akhmylik, a possible variation of the name Yalik, corresponded to a village once located in Yalik Bay. On one trip the priest recorded a weeklong stay in Akhmylik village, providing incidental information on the population as well as giving the impression that additional villages existed close by.

May 22. We came to the Chugach village of Akhmylik. The same day I sent a message to the neighboring settlements, calling the people for prayers, confessions and communion. Giving them two days for fasting, I held services, preached sermons, received confessions, and May 25 gave Holy Communion to forty-eight people. After that I baptized the babies, celebrated one marriage, held requiem service for the dead, investigated the quarrels among the Chugaches, and officiated as peacemaker. On May 29 I sailed farther.... [102]

Prior to arriving in Akhmylik, Abbot Nicholas stopped at the mouth of Kachemak Bay to administer services at the Russian coal mining camp. The decision to exploit the coal deposits opposite Port Graham, as originally noted by Portlock and Dixon in the 1770s, and then later by Doroshin, roughly coincided with the establishment of the Kenai Mission. Though these were unrelated events, both brought increased trade activity and Russian influence to the outer coast.

The Kenai Mission remained a permanent institution in Kenaitze, Chugach, and Dena'ina villages after American acquisition of the territory. Its existence increased the independence of village chapels and called for the consolidation of remote villages.

Russian Coal Mining on the Kenai

Coast

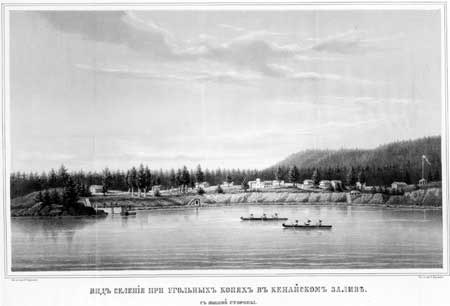

In 1848, the Russians had established Coal Village near Port Graham to serve as the support and export center for coal exploitation along the northwest coast of the Kenai Peninsula. The settlement catered to the mining crews, providing housing and supplies. [103] Supplies arrived from San Francisco via Port Graham on the small ship Cyane, an American ship recently acquired by the Russians. By 1859 the operation expanded to include an entire community, by one account rivaling in size both Sitka and Kodiak. [104] Finnish mining engineer Enoch Hjalmar Furuhjelm, who managed Coal Village, openly praised the village as the "best and most practically planned" in Alaska. [105]

|

| Coal Harbor, near Port Graham, 1786. By Joseph Woodcock, from Portlock voyage. Alaska Purchase Centennial Commission. Alaska State Library, photo PCA 20-101. |

Enoch Furuhjelm, Johan H. Furuhjelm's younger brother and the future governor of Russian America between 1859 and 1863, arrived on the Kenai Peninsula in 1855 after purchasing mining equipment and supplies in California. Because the 1849 California gold rush had placed a premium on coal resources, the Russian government hoped to profit from coal exports to California and compete with coal shipped from England, Chile, and Australia. Despite these high expectations, Furuhjelm found himself strapped with both an inexperienced crew and the need to build a usable mine. Furuhjelm improved the mine, and a modest farming operation started up as a side venture. Typically the mining crew included thirty-eight regular workers and eight day laborers hired from the Native labor pool. The mine site included four levels of adits measuring over 1,600 feet in length.

Furuhjelm's first and only load of coal to California left the mine in 1856 after a desolate winter spent in dirt hovels which left most of his crew incapacitated with disease. The shipment delivered to the West Coast could not compete in price with even lesser grades of domestic and foreign coal. The cost of shipping priced Alaska coal out of the market. Also, as with many ventures taken on by the Russian government in Alaska, demand had peaked by the time they decided to enter the market. In the following account by a crew chief at the mine, it is obvious that a sense of hopelessness surrounded the short-lived operation.

In the year 1858 I was ordered to English Bay or Graham's Harbor, at the entrance of Cook's Inlet, having been attached to the so-called "Kenai Mining Expedition".... My duty was to superintend the Natives and Creoles employed in bring supplies and material to the spot where the coal veins were being developed. The supplies were forwarded chiefly from the Redoubt St. Nicholas [at Kenai] and carried on baidarkas. The work progressed very slowly as the men employed were for the most part entirely unacquainted with underground mining and from the very beginning I never had any confidence in the enterprise. I am sure that as early as 1859 Mr. Furnhelm told me confidentially that he had no faith in the coal mines.... [106]

|

| Coal Village near Port Graham, c. 1860. Russian-Americdan Company report. Bancroft Library. |

Furuhjelm left Alaska in 1862. By 1868 the mine was completely abandoned, as noted in an account by Captain J. W. White of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Wayanda:

Came to anchor off the coal mine (long since abandoned as such, now occupied by an American Fur Company) Captain White with several officers visited the post and examined the premises, found the store house and dwellings locked up, in charge of the Chief, Constantine Kal'iv. [107]

In 1880 William H. Dall toured the mine and offered a candid view of what the mine may have been like twenty years earlier.

In 1880 I visited the site of the workings and found the tunnel inaccessible from the water, which partially filled it and the caving in due to the rotting of the timbering. The works had evidently been of a primitive kind, as there were no permanent buildings and not even a pier for shipping the coal. Only a few pieces of worn-out, rusty machinery and the tunnel in the bluff at the top of the beach remained to show that any work had ever been attempted here. I have seen statements that an extensive stone pier and costly buildings had been erected here and large sums of money lost in the attempt to utilize the coal, but, apart from the intrinsic improbability of such foolish doings, no evidence of the truth of the statements was furnished by the locality itself at the time. [108]

Russian exploration and enterprise along the outer Kenai coast irrevocably changed Native settlement and brought few economic rewards to the Russian-American Company. The radical shifting of Native inhabitants led to the demise of smaller villages and encouraged regional consolidation. Most of the Russian endeavors along the coast, however, included and employed local populations. This action supported Russian enterprise and created an intricate historic context for the outer coast in the 1800s.

|

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, 1920. The Rockwell Kent Legacies. |

kefj/hrs/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002