|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 4:

SHIFTING LANDSCAPE: DEMOGRAPHICS, ECONOMICS, AND ENVIRONMENT ON THE OUTER KENAI COAST

This country is settled by Innuits, who have peopled the east coast of the peninsula, and from there eastward along the mainland nearly to the Copper River. Two of the trading stations in the Kenai district are located among these Innuits at English Bay and Seldovia. [1] — Ivan Petroff, 1884

|

| Map 4-1. Historic Sites-Shifting Landscape. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Abbot Nicholas, the Russian Orthodox priest in residence at Kenai since 1845, died in 1867, the same year that the U.S. government purchased Alaska. With the abbot's death, the Kenai Mission lost its first missionary and priest at a time of transition and uncertainty. Village parishes experienced the same sense of loss. The transfer of Fort St. Nicholas [Fort Kenai] from Russian hands to the U.S. Army occurred in 1869 with little provision for the continuation of services to the villages. In 1870, the Americans abandoned the fort. The closing of Fort Kenai affected trade on the Kenai Peninsula and on Kodiak and Hinchinbrook islands.

The years after 1870, however, brought some positive changes. Once the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC) established itself in southcentral Alaska, a lucrative fur market resumed. In 1881, after years of neglect, the Kenai Mission reinstated a new priest. With this new appointment, a church presence returned to the villages in the Chugach region. These two actions triggered a brief period of prosperity on the outer coast in the late 1870s to early 1880s. When fur prices fell in the late 1880s and the economy of the outer Kenai Peninsula collapsed, the Russian Orthodox Church intervened. The church attempted to stabilize life in the villages, but its success in that endeavor was both incomplete and temporary.

Fur Trading After the Alaska

Purchase

Like the Russians before them, the Americans depended on an economy tied to hunting and fur exports. The high price of fur on the American market encouraged Natives and Euro-Americans to hunt along the outer Kenai coast. Initially, the Americans carried out their business from the same stores and warehouses. The newly formed Alaska Commercial Company acquired the Russian trading post at Alexandrovsk (English Bay). The company hired Native crews to hunt between Seldovia and Nuchek. These two trade centers also supported Russian Orthodox parishes. As Golovin noted in his 1860 survey of the colony, the placement of Russian Orthodox churches was linked to economic centers. He wrote, "For the most part they have been built in areas where there are many Natives, or in places where the natives dispose of their furs." [2]

Both the Russian Orthodox Church and the rise of American fur companies reshaped village demographics on the Kenai Peninsula in the late 1800s. One observer remarked that "The moment you leave Sitka and steer northward, you enter the realm of the North American Commercial and the Alaska Commercial companies: Kodiak, Nuchek, Kenai, Unalaska, with a host of Native Settlements, are completely in their hands...." [3] Both the church and the commercial companies sought to centralize services in larger villages. The Kenai Mission strategically supported the establishment of local churches in villages that had the potential to serve neighboring areas. In addition, the Alaska Commercial and Western Fur companies, as well as smaller independent companies with regional stations, preferred to buy and warehouse fur pelts from crews of Native hunters that operated from one central location.

The availability of Native crews was critical to commercial success; by law only residents and Natives could hunt for furs in the new American territory. In a reactionary ruling of the new government, Section 6 of the Customs Act of July 1868 originally prohibited the killing of any fur-bearing animals within the waters or territory of Alaska. [4] Within two years, the Secretary of the Treasury revised the law to allow Alaska residents to hunt sea otter. [5] By 1879 only Alaska Natives, or whites with Native wives, had the legal right to hunt animals for furs. In yet another radical turnaround, the law changed again in 1893, banning the taking of pelts within territorial waters. The law also limited the use of larger ships–except Revenue Cutters–for transporting hunters. [6]

This succession of laws directly affected crews trying to reach distant hunting grounds and the villages where they traded. The larger ships replaced the smaller baidarkas and bidars, a practice that eventually led to dramatic changes in the use of coastal areas. Larger ships avoided the smaller coastal harbors and beach landing sites. They also had no need for temporary layover spots or shelters during storms. Hunters had fewer opportunities to visit the smaller coves and bays. In addition, as fewer boats traveled from village to village, communication decreased, as did populations.

The Alaska Commercial Company at English Bay

Established as a Russian fortified post in 1786, the settlement of Alexandrovsk, like many Russian holdings and stations, became an American trading station. Although it is not known what remained of the original Russian buildings at the time of American acquisition, Hutchinson, Kohl & Company–the founding partners of the Alaska Commercial Company–purchased Russian properties on the Kenai Peninsula. Alaska Commercial Company logbooks indicate that the company operated a trading station at English Bay at least as early as 1872. An inventory of existing buildings in English Bay taken in 1875 showed that the company maintained a storehouse, a dwelling, a barn, and a store, in addition to stores in the villages of Illiada (Iliamna) and Ostrovsky (in Kachemak Bay). [7] A later survey of the property, in 1879, included the same buildings with an assessed value of $300. A second group of buildings existed on the site which included "a store house valued at $100, a dwelling worth $185, and a second store house worth $40." [8] These buildings may have been the property of an earlier station on site established by Tittle & Company in 1869. [9] Like the Alaska Commercial Company, Tittle & Company was headquartered in San Francisco.

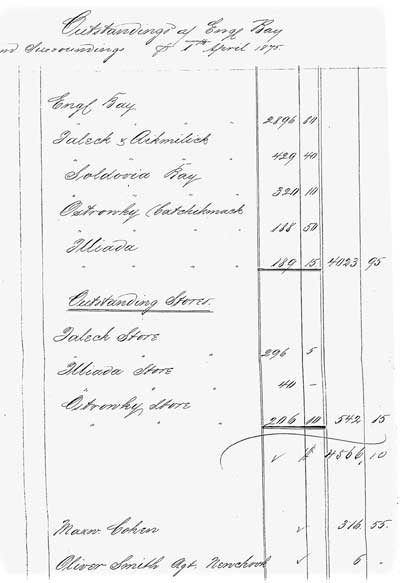

By 1892, the Alaska Commercial Company reported that the Kodiak District, which included English Bay and the Kenai Peninsula, had "assistants at stations scattered along the mainland and islands from Chignik Bay on the west to Prince William Sound on the east and the head of Cooks Inlet on the north, having stores in seventeen Indian villages, which are maintained throughout the year." [10] The English Bay station maintained and supported a number of local village stores and warehouses between 1870 and the early 1900s. In 1875 subsidiary stations and holdings of the English Bay station existed in Yalik and Akhmylik, Seldovia Bay, Ostrovsky or Catchikmack, and Illiama. Station manager Maxwell Cohen and agent Oliver Smith maintained the stores at Yalik, Illiama, and Ostrovsky. [11]

The English Bay station traded with stations on Kodiak Island and in Cook Inlet. Through these contacts, the commercial companies provided income to local hunters and controlled fur markets. At the Alaska Commercial Company's English Bay station, the company maintained detailed records and accounts for each hunter. Hunters sold their furs or applied them towards the purchase of hunting gear. The store kept a ready supply of baidarkas, hunting equipment, food, and household goods. [12] This arrangement almost guaranteed that hunters would become indebted to the company. By one estimate, each Native hunter or head of the family owed $500 to the Alaska Commercial Company. [13]

The English Bay station also maintained a fleet of schooners. Schooner traffic in Cook Inlet regularly carried parties of hunters, and the same activity occurred along the outer Kenai coast. The open waters of the Gulf of Alaska, and the distance between English Bay and Nuchek, added considerable hardship for the hunters. Historian Robert DeArmond noted that:

The vessels owned by the fur companies and used principally to supply the trading stations were also used as tenders for Native sea otter camps, moving the hunters from one point to another during the season. Some of these vessels also served as mother ships for otter hunters, carrying the baidarkas on deck when they were not in use and serving as living quarters for the men. [14]

Company expenditures show that crews traveled to the Barren Islands, the Gulf of Alaska, and to Nuchek. The schooners carried provisions for sea otter parties, and the crew on board purchased skins directly from the hunters. The following entry documented the arrival of hunters to English Bay from Nuchek. [15]

Thus, the schooner Eudora left English Bay on May 2, 1877, for Chonoborough [Augustine] Island with a hunting party, and at the same station on June 12, 1877, "Arrived, eight bydarkas of Nuchek Indians to hunt otter." [16]

The Nuchek hunters may have arrived independent of any schooner but given the option, passage on the larger ship would have been safer and faster. Hunters looking to take advantage of passage between larger villages and hunting grounds gradually moved away from the smaller, remote villages. Many abandoned villages later served as hunting and fishing camps for crews in transit.

The company incurred overhead costs for private baidarkas used by the Native crews. As a rule, the company expected each hunter to pay off the cost of the boat through a personal account. However, it appeared that the company extended more credit to the hunters than it would have preferred. The English Bay station agent, discouraged with the lack of return on this investment, recorded the following situation.

Natives lost 8 bidarkas since last Fall, 3 of them were brand new, a bidarka costs from $40 to $50, although the natives claim the frame as theirs, the Co. had to pay for them all, and charges each part the price of same, $12 for frame and $10 for putting on the Loftock [skin?], might as well give it to them gratis in the first place, as I am satisfied they will never pay it. [17]

The Yalik Bay Store

The Alaska Commercial Company opened a store in Yalik Bay off the West Arm of Nuka Bay in late 1872 or early 1873 and continued to visit and stock it into the 1880s. [18] Company records specifically identified stores at two locations in Nuka Bay. These included a store at Yalik and one in Akhmylik. Company records indicated that agents made trips to each location as well as kept separate operating accounts and expenses for the two stores. However, as mentioned in Chapter 3, Townsend suggested that the two villages were probably the same. It is probable that the Yalik store was built near the village of Akhmylik; it may have been across Yalik Bay or closer to the bay entrance. References to Akhmylik dropped from company records after the late 1870s, while Yalik continued to appear on the books until the mid-1880s. The name Yalik may have replaced the longer village name and eventually meant any settlement in the Yalik Bay area. [19] Petroff refers to Yalik as a village name in 1884 as does Porter in 1890. [20] Given the chance, the government readily used a more anglicized name and thought little of changing local place names. This may have occurred in the case of Akhmylik and Yalik.

The Yalik store probably stocked a portion of the merchandise found at the English Bay station. This included a selection of general dry goods, cloth, shoes, cooking utensils, religious objects, toiletries, specialty items, and all types of hunting and fishing equipment. Employees at the English Bay station regularly made trips to both Yalik and Akhmylik. The purpose of their trips was not evident from the notations made in the station log, but there could have been periodic buying expeditions. The station also paid wages to the village chief on a monthly basis. (Records indicate, for example, that English Bay Chief Constantine Kal'iv received checks from the company.) [21]

In October 1877, the English Bay log showed an expense of $28 for the closing of the Yalik store, with a follow-up entry in the next spring to move a "warehouse in the bay." Although there was no specific reference that this was the Yalik Bay warehouse, this entry indicated that the company commonly reclaimed and moved its buildings; this procedure could have occurred at Yalik Bay. Company involvement and trips to Yalik continued despite the apparent store closing. In 1880, the company recorded an expense of paddles for the store; that April, merchandise on hand at the store totaled $147. The existence of these transactions implies that there could have been some confusion in the records. Perhaps the company meant to document the closure of the Akhmylik store and not the one at Yalik.

Frank Lowell: Hunter, Trader, and Station

Manager

Small independent hunters and traders often acted as intermediaries between Native hunters and the established trading stations operated by the Alaska Commercial and the Western Fur and Trading companies on the Kenai Peninsula, on Kodiak Island and at Nuchek. Similar practices supported Native hunters on Cook Inlet and throughout the Dena'ina region of southwestern Alaska. [22] Porter reported in the 1890 census that "the scattered white traders were lavishly supported with ‘outfits', comfortable houses, and native hunting parties, all on long credit, in order to secure their trade and custom." [23] On the outer coast of the Kenai Peninsula, Frank Lowell maintained a local hunting and trading network that was for many years affiliated with the Alaska Commercial Company's English Bay station. In 1911 Benjamin L. Johnson, a USGS surveyor, mentioned a second independent trader, a man he only referred to as Kimball, who "handled furs for the Natives..." and "had several trading stores here." [24] Lowell and his extensive family traded and sold furs on the coast for approximately fifteen years.

Frank Lowell was born in Maine and homesteaded on the Kenai Peninsula with his wife, Mary Lowell, a Native of English Bay. In 1906, an article in the Seward Weekly Gateway reported that in 1883, the couple moved to the site near the head of Resurrection Bay. [25] Frank Lowell apparently left his wife and family in 1893 but Mary Lowell, who was of both Russian and Native ancestry, remained on the homestead until after the turn of the century. [26] Mary Lowell died on May 20, 1906. Soon afterward, the Seward Weekly Gateway ran the following obituary.

Mrs. Lowell was born at English Bay near Seldovia, on the seaward side of the peninsula. She came to the present site of Seward with her husband 23 years ago and had lived here ever since. Her husband left here around 13 years ago but Mrs. Lowell continued to reside on the old homestead with her children [27].

|

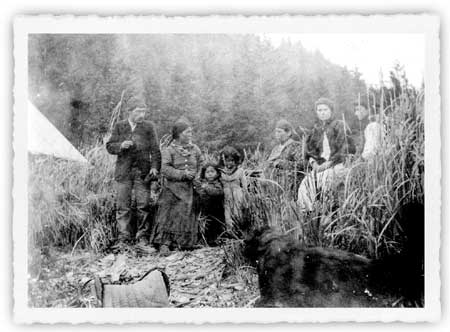

| Mary Lowell (second from left) and her children wre part of the only family settled at the head of Resurrection Bay before Seward townsite was founded in 1903. Courtesy Resurrection Bay Historical Society. |

In 1898 Walter Mendenhall, the USGS geologist mentioned in Chapter 1, met a group of Natives at the head of Resurrection Bay who were planting potatoes and other vegetables. These people were probably members of the Lowell family. Mendenhall noted four or five houses along the bay. The Lowells provided Mendenhall with a small boat to reach the head of the bay, approximately four miles north of where they docked a steamer ship. [28]

Frank Lowell kept business contacts in English Bay until at least 1895. Benjamin Johnson, the USGS surveyor, suggested that he supported other families of his own who also lived along the coast. [29] Census taker Robert Porter, however, stated in 1890 that Frank and Mary Lowell and their children comprised the only residents of the coast.

The only settlement on this whole coast, extending for 120 miles from Cape Puget to Cape Elizabeth is the place of residence chosen by a native of Maine upon the shore of Resurrection Bay, or Blying sounds. This man who is one of the American pioneers of Alaska, entered the territory almost immediately after its purchase by the U.S., and has never left it. He has named his home Lowell, after himself, and having married a creole wife, has reared a large family of stalwart boys, expert hunters and sailors, who assist their father in his hunting expeditions in a small schooner owned by the family. [30]

|

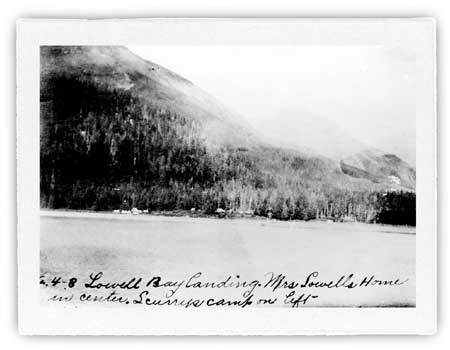

| Before Seward was founded, "Lowell Bay Landing" appeared as shown. Courtesy Resurrection Bay Historical Society. |

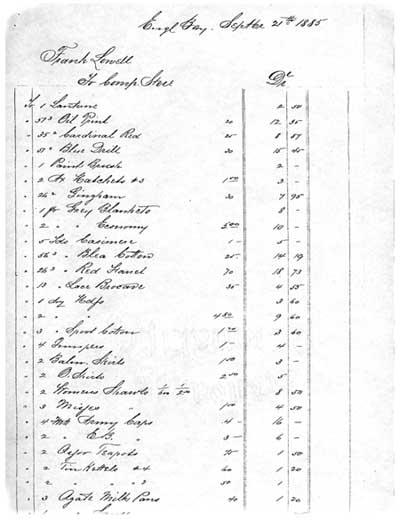

Frank Lowell worked as an independent trader and as an Alaska Commercial Company agent. He maintained a long-term relationship with the ACC's English Bay Station. He also worked with Charles Smith at the Western Fur and Trading Company. From 1877 to 1895 if not longer, Lowell kept both personal and business accounts at the English Bay Station. His private accounts reflected a need for a wide range of household supplies in addition to luxury and personal items. These purchases give a glimpse into Lowell's personal life and of the products available on the coast in the late 1800s. Lowell regularly bought silk, guitar strings, children's shoes, cakes of fancy soap, needles, smoking tobacco, tea, sugar, lead, and powder. He also purchased a chinchilla cap, a gold ring, cologne, lace brocade, and teapots.

|

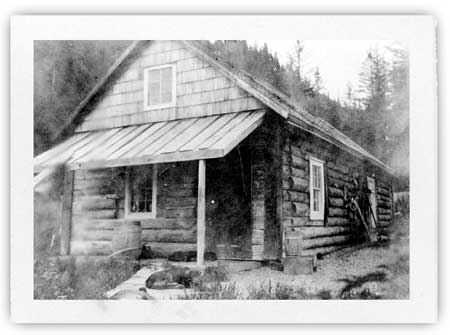

| The Lowell cabin, around which Seward townsite sprang up in 1903. Courtesy of Resurrection Bay Historical Society. |

Lowell also maintained an account for his hunting crew at the English Bay station. Although Native hunters kept individual accounts for both furs sold and goods, Lowell subsidized some crewmembers. He regularly helped hunters who were no longer able to pay their debts, and he often traded on their behalf. Lowell's crew hunted and set up winter camps at many points along the coast between English and Resurrection bays, including Yalik, Nuka, and Aialik bays. [31] The principal furs hunted and traded were black bear, gray fox, black fox, marten, and mink, along with sea and land otter skins. Another trader named Smith, perhaps the Charles Smith who shared an account with Lowell at the Western Fur and Trading Company, also had Native hunters in his employ with Alaska Commercial Company at English Bay. [32]

|

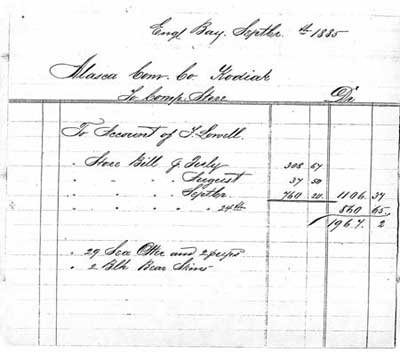

| Frank Lowell, English Bay Company Store Account, 1885. Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ACC Records, Box 8, Folder 104, Accounts-Outstanding, 1872-1897. |

|

| Frank Lowell, English Bay Company Store Records, 1885. Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ACC Records, Box 8, Folder 94, Accounts-Outstanding, 1873-1884, 1 of 2. |

|

| English Bay Outstanding Accounts, 1875. Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. |

|

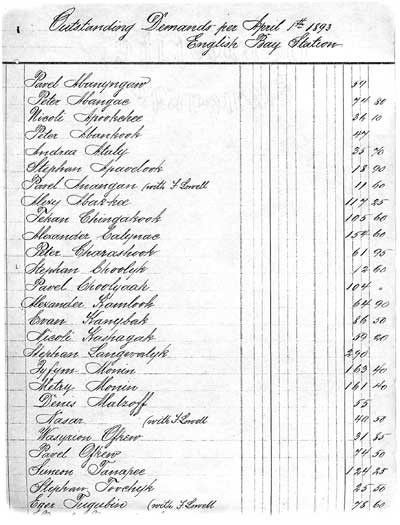

| English Bay Station, Outstanding Accounts, 1893. Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ACC Records, Box 8, Folder 104, Accounts-Outstanding, 1872-1897. |

The Western Fur Company and the Collapse of

Fur Prices

Established in 1879, the Western Fur and Trading Company, another San Francisco based outfit, became the Alaska Commercial Company's principal rival on the Kenai. With trading stations at English Bay, Kenai, Tyonek, and Douglas, the Western Fur and Trading Company managed a large proportion of local trade until the early 1880s. In 1883, the Alaska Commercial Company bought the Western Fur Company for $175,000. [33] The ACC was left with no competition to share the enormous debt and to inflate prices, and fur prices plummeted. As a result, the ACC entered into a period of tighter management. The company closed stores and probably felt less of a need to provide local services in the smaller villages. This move forced the labor force to come to them, rather than the other way around. As a result, a growing number of small private hunters began to cut into the company's profits.

The implications of only one major fur company operating on the lower Kenai Peninsula had a resounding affect on all the villages. The following synopsis of what happened in Seldovia may have been equally relevant for the hunters on the outer coast, especially those who had benefited from unlimited credit at a time of artificially inflated prices. Anthropologist Joan Townsend provides the following chronology.

[During the 1870s, a] hunter was given advances of food, clothing, hunting equipment and luxury goods with the understanding that he would bring his furs to that company. Hunters again often found themselves in debt to the traders. Fur prices, after the sale of Alaska, began to rise because of the competition of the Alaska Commercial Company, particularly with the Western Fur and Trading Company. Excessive credit was given to good hunters and prices paid for furs were often on par with those paid in San Francisco.... In 1883, the Western Fur and Trading Company went out of business, leaving the Alaska Commercial Company in a monopoly position except for the presence of a few small independent traders. Prices paid for furs dropped quickly, credit was terminated and the company made efforts to collect outstanding debts. [34]

Between 1881 and 1883 Johan Adrian Jacobsen, a Native Norwegian, toured the Alaska coast as part of a German team sent to collect artifacts for the Royal Museum in Berlin. Passing through Seldovia on his way to English Bay, he noted the fall of fur prices.

Here we found the dwellings that the sea otter hunters we met the night before had used. This village had been the location of a trading post of the Western Fur Trading Company that had been abandoned in May. Because of this the price of a good sea otter pelt fell from $112 to $35. [35]

Jacobsen noted that Ivan Petroff, while working on the 1880 census, had followed a similar itinerary only a few years earlier. Jacobsen had begun his trip around the peninsula in Kenai. Thinking it best to cut across the peninsula at the northern end of Cook Inlet and take passage on a boat from the Pacific side, Jacobsen changed his plans once he learned that there would be no one to assist or meet him. In his journal, he recounted the advice he received:

...But Mr. Wilson [Capt. James Wilson], who best knows the condition of this area, urged me against this, assuring me that I could not get any men on the east side of the peninsula. He had recommended this route to the well-known American traveler Mr. Petroff, who was forced to return. Mr. Wilson suggested as an alternative that I go to Fort Alexander [English Bay] in the southern part of the Kenai Peninsula.... [36]

Following the trail of villages from Kenai to English Bay by boat, Jacobsen arrived at the Alaska Commercial Company station in English Bay. There he visited with Maxwell Cohen, originally from Berlin, who had lived in the region for many years and took a great interest in local affairs. As station manager, Cohen was very knowledge of the terrain, routes, and village locations, and Jacobsen relied on his advice and insight about the region. [37]

The Influence of the Kenai Mission after 1867

Jacobsen's visit occurred just before the Alaska Commercial Company closed the Yalik store and the Russian Orthodox Church resumed its customary practice of visiting Native parishes. Following the death of Abbot Nicholas in 1867, Makar Ivanov had temporarily assumed the responsibilities of the Kenai Mission. Of both Russian and Native descent and trained in Nushagak, Makar Ivanov managed the church in Ninilchik and Tyonek as well as Kenai. [38] Devoted to the mission until his death in 1878, Makar Ivanov probably did not travel to the outer coast. In the interim, these villages may have turned to Alexandrovsk for services and to keep in contact with news from Kenai. In 1880, residents at Nuchek, the farthest point east on the coast in the Kenai Mission, had not seen a traveling priest in nine years. [39] Despite the lack of clergy, local communities in the region continued to gather once a year with the hope that a priest would appear. By 1881 Heiromonk Nikita had officially acquired the duties of the Mission. That year he re-established the practice of regular visitation to outlying villages. [40]

Although the new heiromonk resumed travel and contact to villages, his travel log refers to trips only as far south as Alexandrovsk. Acutely aware that the cost of travel prohibited a more extensive itinerary, the Heiromonk criticized the lack of funding and the effect it had on his actions.

I think the Alaska Ecclesiastical Consistory was unjust in cutting down the travel expenses of the Kenai missionary from $100 to $50, the more so that even $100 was far from being enough for that purpose.... I, being a monk and consequently a single man, willingly sacrificed my own salary without care or thought of the future, but for a married missionary it will be very difficult. [41]

Heiromonk Nikita's travel journal entries documented a period of decline on the Kenai. He wrote of disease, a series of natural disasters, and the collapse of higher fur prices; all of these events were concerns of the church, inasmuch as they affected the livelihood of its parishioners. Dismayed by what he observed, Heiromonk Nikita reported in 1885 that

There is so much poverty and need in the mission. In each village one may always see deformed, destitute people, blind, lame, cripples, walking and creeping on the ground, practically naked, in ragged shirts.... [42]

In a report dated May 28, 1884, the Heiromonk described an influenza epidemic which claimed the lives of nearly all the children two years old and under in Kenai, Ninilchik, Seldovia, and Alexandrovsk. This tragedy occurred at approximately the same time as the eruption of Mount Augustine, known locally as Chernabura Volcano. [43] The ensuing tidal wave flooded the village of English Bay, causing the residents to flee to higher ground. William Dall described the destruction caused by the volcano.

The eruption referred to was accompanied by tidal waves and vast clouds of ashes, which were wafted to a great distance. On the west side of the inlet hundreds of square miles of spruce forest was killed by the load of wet ashes, which descended on this occasion. [44]

All of these factors, as well as a Russian Orthodox Church effort to consolidate Native villages and cut travel costs, may have led to the relocation of residents from Yalik and other outer coastal villages. In 1880, the U.S. Census Bureau contracted the first government census of the new territory and hired Ivan Petroff to travel throughout the villages of the Kenai Peninsula. Enumeration of villages for the outer coast was limited. In total, Petroff included eleven villages on the Kenai Peninsula in the census report. He specifically identified the eastern coast of the peninsula as a separate area and included the village of Yalik. Petroff recorded a population of thirty-two Natives, with no resident creole or white inhabitants. [45]

Several sources have indicated that within the next ten years, Yalik residents had moved from their village. [46] Frank Lowell, who was the 1890 Census's special agent assigned to the Kenai Peninsula, noted in his travel log that English Bay was the southernmost village on the peninsula that he visited. [47] In the census report, Porter stated the following.

Ten years ago a settlement of Chagachigmiut existed in Ayalik bay, a few miles west of Blying sound [the mouth of Resurrection Bay], but upon the advice of a monk in charge of the Russian mission on Cook inlet they migrated to the settlement of Alexandrovsk, on English Bay, beyond Cape Elizabeth. [48]

Many unanswered questions surround this possible confusion between the village of Yalik on Nuka Bay listed in the 1880 census and an unnamed village in Aialik Bay. [49] Archeological evidence and oral tradition support the existence of a village or settlement in Aialik Bay at some time in the last century; Porter, however, probably misspelled the name Yalik or a variant of Akhmylik into a word that closely resembled Aialik. The confused geography could also be explained through Porter's (or Lowell's) unfamiliarity with the coast.

Native Labor and the Rise of the Fishing

Industry

Changes in the Kenai Peninsula's resource base affected the use and appeal of natural resources on the outer coast as compared to other areas. These changes gradually served to attract people to Seldovia, Port Graham and other villages in Cook Inlet. As hunting proved more challenging and less profitable to American companies and their Native crews, a new economy began to emerge that ultimately replaced the fur trade monopoly. By the late 1880s, commercial fishing and canneries gradually succeeded hunting and fur trading as the major source of local Native income but by 1890, the Alaska Commercial Company's English Bay facility was the only remaining trading station on the Kenai Peninsula. [50] As Porter points out, English Bay and Seldovia were already well established church communities, probably because they had been trading station sites.

The settlements of Seldovia and Alexandrovsk [English Bay] have small chapels built of logs, one of the residents in each serving as reader, and once or twice during the year the priest from Kenai visits these localities. [51]

The salmon cannery industry began on the Kenai Peninsula in 1882 with the establishment of the Kasilof River cannery. Built by the Alaska Packing Company of San Francisco, this was the first of many canneries to process Cook Inlet salmon. [52] Over the next decade, seventeen out-of-state companies built canneries in central Alaska; during the 1890s, many of these became part of the Alaska Packers Association.

Canneries relied on a seasonal workforce with a highly segregated and hierarchical division of labor. Cannery management, recognizing the limited local population base, brought a white and Oriental labor force north each spring; Native hiring also occurred, though on a relatively small scale. These early canneries may have had an indirect effect on the economies of Seldovia and English Bay by siphoning local labor away. For Native residents, the canneries' impact on the Kenai Peninsula's resources and environment proved overwhelming on an individual and personal level.

Father John Bortnovsky, who presided over the Kenai Mission from 1898 to 1908, observed and recorded how the demise of the hunting-trading system undermined the Kenaitze's environment and the lifeways. As neighbors to the Chugach, the Kenaitze depended upon similar resources; as the people of the coast migrated northward, the two groups invariably faced many of the same economic hardships and influences. Written in 1899, Bortnovsky's account of the onset of change on the Kenai conveyed a sense of loss and isolation for the Natives as outside interests invaded the peninsula.

The hunting grows poorer. Frequent forest fires caused by American prospectors either exterminate the animals or drive them to safer places. The latter would not have caused too much hardship: the Kenai Indian is accustomed to roaming in the mountains and on the tundras; he can reach the animals anywhere and catch them. But, unfortunately, another scourge fell on them and completely depressed them: the fur prices fell terribly.... The quantity of fish grows smaller each year. And no wonder: each cannery annually ships out 30,000 to 40,000 cases of fish. During the summer all the fishing grounds are jammed with American fishermen and, of course, the poor Indian is forced to keep away in order to avoid unpleasant meetings. [53]

By the early 1900s, salmon canneries ruled the local economy on the Kenai. Cannery operations provided local stores for fishermen and workers that eventually took trade away from the fur company stations. For the residents of English Bay looking to find work in the fishing industry, two canneries opened on the southern end of the peninsula in the early 1900s. Between 1911 and 1915 the Seldovia Salmon Company operated a cannery at Seldovia. Unable to turn a profit, the company defaulted in 1915, and remained closed for a year until the Columbia Salmon Company invested in the buildings in 1916. Within a year, the Northwestern Fisheries Company bought a cannery and kept up the operation for two more years until it closed indefinitely in 1919. At Port Graham, the Fidalgo Island Packing Company built a cannery in 1912. Already established in the southeast market with a cannery in Ketchikan, the Fidalgo Island Packing Company maintained an operation at Port Graham until 1960 if not longer. [54] Other employment could be found at the halibut cold storage plant in Port Chatham that opened in 1915, and at Portlock where a chrome ore mine opened in 1917 on Claim Point. [55]

Port Graham, a settlement with a population of 100 residents by 1910, provided a variety of job opportunities in shipping, fishing, and coal mining. In 1909 the site became a transfer point for local shipping traffic into Cook Inlet. Port Graham had an excellent harbor as compared to neighboring English Bay less than five miles away. The USC&GS reported on the port in 1910, describing it as a secure two-mile-wide harbor with easy access in daylight; the agency further described the port as being located inside Passage Island between Russian Point and Dangerous Cape. [56] As Port Graham (along with nearby Seldovia) prospered and attracted new industry, English Bay remained unchanged. The traditional Native community relied on its strong church and former hunting and trading affiliations to maintain its seasonal population. It is unknown if the shipping industry sought and hired local Native employees; the larger ships anchored in the waters off English Bay did hire Native rowers to shuttle ship passengers to shore. [57]

With the renewed interest in the Port Graham area, investors and miners once again attempted to exploit coal resources along the shores of the bay. W. G. Whorf, who worked with both the cannery and coal mine, in Port Graham procured the government railroad contract to ship coal to Seward. [58] Coal mining continued at least through 1918 in Port Graham under the management of the Port Graham Coal Company. [59] Native crews from the region worked the mines and lived nearby. In 1910 the ruins of the earlier mine were still standing and some activity had already resumed.

Here Russia had a coal mine ... and sent its criminals there to work it. The mine is abandoned, but there is one nearer the bay. There is an Indian village here and they work in the mine, which is not deep. Here and in other places it is put in sacks. Several thousand sacks of coal were near the mine. The ruins of the Russian buildings were seen, one of them being a large prison, another a church.... [60]

Transient work and seasonal occupations shaped a pattern of migration between villages and larger economic centers at the turn of the century. In 1898, Dall reported in the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society that residents moved freely between Seldovia and the Port Graham area to find work.

In the lower bay outside of the harbor is a snug anchorage, Chesloknu of the natives, Seldovia or Herring Bay of the Russians. Here are two trading stations, and most of the inhabitants from Port Graham, where the harbor is less convenient, have migrated to Seldovia village. [61]

By 1898, the church had opened a school in Alexandrovsk and employed Ivan Munin as the first teacher and administrator.

During the last few years of the nineteenth century, American shipping routes from Seattle and San Francisco began to link many villages and towns throughout Alaska. Three of the principal means of transport–ships carrying mail, the Revenue Cutters, and commercial company supply and stock ships–for the most part skirted the outer Kenai coast. Ship traffic later served Port Graham and Seldovia, but the tides within Cook Inlet proved too treacherous for steamer ships, requiring smaller ships to lighter mail and supplies to towns and villages. Larger ships had little incentive to linger along the outer coast, at least not until the initial stages of reconnaissance and construction of the town of Seward in 1902-03 as the terminus of the Alaska Central Railroad. By 1911, the Alaska Steamship and Alaska Commercial companies were serving Seward with mail six times a month. [62]

This period of transition along the coast, as people moved between villages and new industries evolved, changed local economies and village life. In 1902, Mary Lowell sold the rights to her family's homestead at the head of Resurrection Bay to John Ballaine as part of the development of the Alaska Central Railroad and the establishment of Seward. As more industry and transportation centered in Seldovia, Port Graham, and Seward, the coast continued to serve as a seasonal hunting grounds until fur farming and gold mining developed in the 1920s.

|

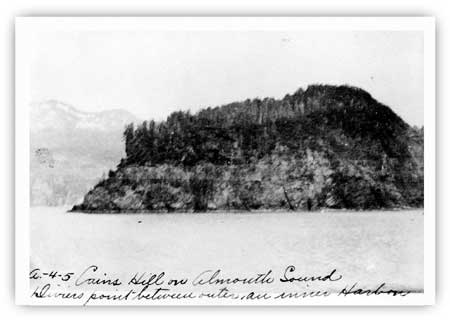

| Caines Head was the site of a major World War II camp; a major gun battery was placed on the hill's crest. The site, which overlooked "Almouth Sound" (Resurrection Bay), was named for Capt. E. E. Caine, skipper of the Santa Ana, which brought the founders of Seward northward in August 1903. Courtesy of Resurrection Bay Historical Society. |

kefj/hrs/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002