|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 5:

BUILDING THE TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE

During the mid-to-late 1890s, a series of interconnected events–the Hope and Sunrise gold strikes, the Klondike gold rush and U.S. Army Capt. E. F. Glenn's expedition–brought dramatically increased attention to Alaska in general and the Kenai Peninsula in particular. The prosperity brought on by the gold rush, moreover, spawned scores if not hundreds of proposed railroad lines. Of those, the only major line that was actually constructed was the White Pass and Yukon Route, built from Skagway, Alaska to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory from 1898 to 1900.

The Alaska Central Railroad and the Founding

of Seward

|

| Map 5-1. Historic Sites-Transportation Development. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As the twentieth century dawned, the vast interior region of Alaska remained inaccessible. Even though the interior was still largely devoid of non-Native settlement, a number of dreamers were convinced that the interior would grow and prosper if a railroad route could be constructed there. Several of these entrepreneurs organized development companies. Between 1900 and 1903 a total of nine railroad companies selected Valdez, at the northeastern end of Prince William Sound, as their ocean terminus; several of these companies, including the prominent Morgan-Guggenheim syndicate, backed up their plans by sending in survey crews. [1] Other development interests trumpeted the advantages of rival ports including Katalla, Nelson (later Cordova), and Portage Bay (later Whittier). Off to the west, activity centered around Iliamna Bay, on the west side of Cook Inlet. The Trans-Alaska Company, led by a Seattle engineer named Norman R. Smith, laid out a sled trail (a predecessor to a railroad) from Iliamna Bay to Nome during the winter of 1901-02. Three years later, the Alaska Short Line and Navigation Company surveyed a route from Iliamna Bay to Anvik. Several of the companies aiming toward Alaska's interior went so far as to grade several miles of right-of-way; inland from Katalla, rails were actually laid for a short distance. But none of these companies was successful in building an intercity railway. [2]

The Alaska Central Railroad Company was different. It was the brainchild of Seattle businessman John Ballaine, who had had a long political and military career in Washington state. In 1900, Ballaine began to study ways to develop a railroad on a new frontier, and in that pursuit he searched for "an all-American route through all-American territory to develop all of Alaska." He concluded that the easiest route for a railway connecting an ice-free port and the interior lay across the Kenai Peninsula and up the Susitna Valley to the Tanana River valley. His search for a harbor led him to the future site of Seward. In March 1902, he helped organize a company to further his goals, and three months later he sent two survey parties to the area to reconnoiter the proposed townsite and right-of-way. After their return, Ballaine wrote that "Resurrection Bay alone, opening directly to the ocean on the south side of the Kenai Peninsula, answered all my requirements to perfection." [3]

A year later, Ballaine proceeded to put his plans into action. The company purchased Mary Lowell's homestead (the only private land in the area) and filed a townsite plat in order to gain title. Company officials then began constructing a dock and roughing out a street grid. That summer, Ballaine and his settlement party left Seattle on the steamer Santa Ana, piloted by Capt. E. E. Caine. On board were 25 company employees, 35 other passengers, 14 horses, a pile driver, a sawmill, and tons of provisions. The ship arrived at the new townsite on August 28, 1903–a date that has since been celebrated as Seward's founding date–and the party began to improve the area. The following April, company officials met on the dock and drove the first spike for the newly christened Alaska Central Railroad. By July 4 of that year, rails had been extended seven miles to the north.

Construction proceeded by fits and starts. By the end of the 1904 construction season, tracks extended 20 miles north of Seward, and a year later, tracks had been built into Placer River valley, another 25 miles up the line. (By August 1905, work had progressed to the point that steamers were being employed to move men and materials between Seward and Turnagain Arm. [4]) But after the 1905 season, work slowed due to the physical and financial difficulties involved in constructing the bridges and tunnels that constituted the so-called "Loop District." Two other events compounded Ballaine's difficulties: first, President Theodore Roosevelt's November 1906 decree withdrawing Alaska's coal lands from development, and second, the financial panic of 1907. Despite those blows, construction proceeded apace, and by November 1909 rails had been completed to Kern Creek (near present-day Portage), 71.5 miles north of Seward. [5]

By then, Ballaine's luck had run out. A year before, in September 1908, the railroad had gone into receivership, and without prospects for an immediate financial turnaround, the company was sold during the winter of 1909-10. The new Alaska Northern Railroad, however, was even less successful than its predecessor had been. The new owners, hoping to cut their losses, built no new track; they offered minimal service and allowed the line to deteriorate. [6] Seward's economy during its first decade of existence was almost completely dependent upon railroad construction activities and ancillary port functions. The town, built on speculation, was thus healthy and growing during its first several years of life. After the railroad went into receivership, however, dull times predominated for the next several years.

Seward's fortunes were revived in August 1912, when the U.S. Congress passed the so-called Second Organic Act for Alaska. Among its provisions, the bill created an Alaska Railroad Commission to investigate the railroad situation. Five months later, the commission concluded that a system based on private capital combined with government land grants was an unworkable way to construct a railroad into the Alaskan interior. (This system had been highly successful in the development of railroads in other western territories. Grim experience, however, showed that it fell short in areas where population and resources were largely absent.) The commission, therefore, recommended that the government purchase the existing Copper River and Northwestern Railroad (which ran from Cordova to Chitina and on to Kennicott), then construct a railroad from Chitina north to Fairbanks. But before that plan could be carried out, Woodrow Wilson defeated incumbent William Howard Taft and another challenger in the 1912 presidential election.

Shortly after Wilson took office in March 1913, he appointed a new team, called the Alaska Engineering Commission, to study the Alaska railroad problem. While the Commission was deliberating, Congress passed a bill, in March 1914, which authorized the construction of a railroad connecting interior Alaska to an ice-free port. No decision had yet been made regarding what route would be chosen, however, and for the next year speculation was rampant over that question. Although four routes were ostensibly being considered, the two serious contenders were an eastern route that would have ascended the Copper River valley and a western route that would have tapped the Matanuska and Susitna valleys. The three AEC commissioners, lured by the possibility of gaining access to the agriculture and minerals of the Matanuska and Susitna valleys, focused most of their attention on the western route. Thus it was not altogether surprising when, in April 1915, President Wilson announced his choice of the route connecting Seward and Fairbanks. By adopting this choice, the government agreed to purchase two bankrupt railroads: the Alaska Northern route, north of Seward, and the Tanana Valley Railroad, in the Fairbanks area. [7]

Seward, as a result of that decision, entered a new period of prosperity. For the next several years, hundreds of workers invaded town as the old Alaska Northern tracks were upgraded and, in places, rerouted. Economic activity remained high until the line was completed in the early 1920s. (Track laying was finished by February 1922, but the line was not open to through traffic until February 1923.) Early in the construction period, in November 1916, the AEC dampened Seward's economic spirits by moving the railroad's headquarters from Seward to Anchorage. Even so, the railroad remained a vital part of town life. Until the advent of World War II, Seward's economy continued to rely on two primary activities: the railroad and the port. [8]

Shipping Activities Along the Kenai

Coastline

Prior to 1900, little commercial shipping took place along the southern Kenai Peninsula coast. Between 1900 and 1920, the only significant non-Native population cluster was located in Seward, where economic activities centered on railroad construction. As a result, much of the shipping that took place along the Kenai coast centered around the movement of railroad workers and supplies. After the railroad was completed, coastal shipping served a variety of economic activities. Both ocean liners and smaller boat service connected Seward with various Cook Inlet communities, Kodiak Island communities, and points "to the westward:" the Alaska Peninsula, Aleutian Islands and Bristol Bay. Most of the traffic along the southern Kenai coastline was going to or from Seward. On occasion, however, ships sailing more distant routes sought out the shelter of the Kenai's bays and coves during stormy periods, and some of those ships anchored there for fairly extended periods.

Ships have likely ridden out storms in refuges along the Kenai coast for hundreds of years; Natives, Russians, and perhaps other European explorers have all doubtless taken advantage of the many irregularities along the coast for that purpose. Perhaps the first recorded instance of shelter-seeking took place in 1896, when a party of miners, one of whom was George Stinson, was blown off course on its way to the Hope and Sunrise gold camps. A news report, printed years later, noted that on a westbound trip from Kayak Island toward the gold camps, the miners became so seasick that they decided to hove-to in Nuka Bay and rest for a few days. Rich-looking float [9] was picked up on the beach, but the miners were more interested in the rich Hope placer diggings, so little attention was paid to their find. [10]

During the Klondike gold rush of 1897-98, one of the major routes that took stampeders to the gold fields was the so-called "rich man's route" that connected Seattle to St. Michael by way of Unalaska. Some of the ships that plied this route followed a more-or-less direct line between Seattle and Unalaska, and this route took stampeders hundreds of miles away from the Kenai coastline. But during the summer of 1897, when the gold-rush frenzy was at its highest, a number of vessels which were clearly unseaworthy were hauled out of retirement for the voyage north; many of these craft, for reasons of safety, took a more circuitous coastal route. [11] That winter, the Moran Brothers Company began constructing twelve nearly identical riverboats in its Seattle shipyards. They were completed in May 1898, after which the company attempted to sail them to St. Michael for use along the Yukon River. The shallow-draft boats were unprepared to travel in the stormy seas of the Gulf of Alaska, so they skirted the coast as much as possible. [12] Despite their caution, a storm on June 23 forced the fleet to retreat to an unknown cove in Nuka Bay. As noted in the diary of an unidentified carpenter who sailed on the steamer Seattle,

Thursday, June 23. The signal was flying on board the Pilgrim "make for shelter," and the fleet turned off of the course it was taking. About an hour and half's run carried us to a snug little harbor called Nuka Bay. At 4:30 p.m. it commenced raining.

Friday, June 24. [After filling the water barrels and repairing faulty hog chains,] some of the men went on shore with paint and brushes and painted on a large rock in big letters "Moran's Fleet Harbor, June 23, 1898."

Saturday, June 25. The Seattle went along side the South Coast and took on fifty tons of coal.

Sunday, June 26. Left Nuka Bay at 5:30 a.m. Steaming against the light head-wind which kept increasing until we again had to hunt a sheltered spot. We put in behind Chugach Island in a place called Port Dick, dropping anchor at 11 a.m. [13]

Since that time scores if not hundreds of ships have unintentionally visited the coves and bays of the present park, some for several days at a time. These have included crab boats sailing along the coast, halibut and cod boats escaping from Portlock Bank, coastal steamers, tourist craft, and state ferries traveling between Seward and Kodiak. As Josephine Sather, a longtime Nuka Island resident, noted, "Many boats came into Nuka Bay, some simply to visit us; some seeking shelter from a storm or a dark night; a few in tow with their engines broken down." [14]

|

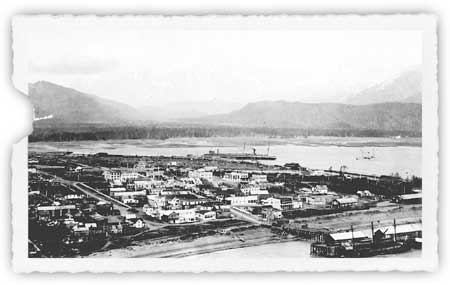

| Seward, as it appeared circa 1923. The railroad dock is at bottom right; the San Juan dock is in the center of the photograph. Neville Public Museum, photo 5671.10. |

After the founding of Seward, much of the coastal shipping for the next several years supported railroad construction activities. The Alaska Central laid tracks for approximately 70 miles north of Seward. Beyond the end of track, grading crews worked for several miles more and company surveyors canvassed the entire 350-mile route to Fairbanks. In order to expedite track-laying activities at the northern end of the Kenai Peninsula, many ships (as noted above) circled the western end of the Kenai Peninsula during the first decade of the twentieth century. These coastal shipping activities continued, first by private firms and then by the Alaska Engineering Commission, until the Alaska Railroad was completed. [15]

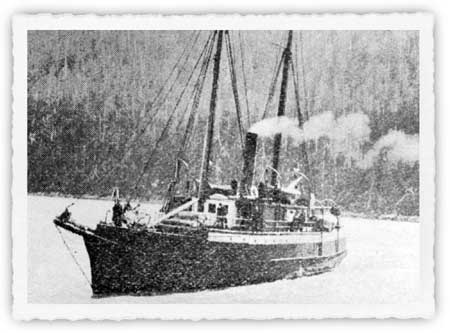

Long before the frenzy of railroad construction died down, shipping traffic based on other needs surfaced. As early as 1903, ships from Seattle regularly served Seward. Companies that served Seward during its first decade of existence included the Alaska Steamship Company ("Alaska Steam"), Northwestern Steamship Company and Alaska-Pacific Navigation Company. All three firms at one time or another owned the Dora, a workhorse craft that had first visited Resurrection Bay in 1896. The Dora remained in the area for many years thereafter, connecting Seward with points on Kodiak Island, the Alaska Peninsula, the Aleutian Islands, and Bristol Bay. [16]

|

| The steamer Dora sailed along the Kenai Peninsula's southern coast, and to "westward" points, during the late 19th and 20th centuries. The Pathfinder, May 1920, 3. |

In 1912, growth in what was then known as "southwestern Alaska" convinced the Alaska Steamship Company to begin serving Cook Inlet points. Two years later, the government's decision to construct a railroad bolstered traffic volumes. Then, in 1916, the Pacific Steamship Company ("the Admiral Line") began competing against Alaska Steam. The two companies brought both residents and tourists into the area; they continued to compete for traffic until the Admiral Line faded away in the spring of 1933. Both carriers featured Seward on their itineraries, and both sailed around the Kenai into Cook Inlet as well. The Admiral Line engaged in local service shipping in Cook Inlet throughout this period, typically serving Seldovia, "Ninilchick," and Anchorage. Alaska Steam, however, discontinued its regular Cook Inlet operations after the 1916 season, probably because the railroad had been completed from Seward to Anchorage that year. [17] No major carriers are known to have plied the waters of Cook Inlet after 1933.

|

| Ships such as the Alaska Steamship Company steamer Alaska brought tourists from Seattle to Seward and other Alaska points during the 1920s and 1930s. Neville Pulic Museum, photo 5670.10. |

Local newspapers provide specifics about the Admiral Line and Alaska Steam ships that provided Seward-Seldovia service between the two world wars. In 1919, the Admiral Watson sailed between the two points, [18] but during the early 1920s both the Admiral Watson and the Admiral Evans ships plied the route. [19] By 1927, both the Watson and the Evans remained on the route, but only on an intermittent basis, and by 1929, only the Watson remained. [20] The only known Alaska Steam vessels serving the route during this period were the S.S. Redondo and the S.S. Curacao, which made occasional trips to supply area canneries. [21]

Those who lived and worked in Cook Inlet, however, demanded transportation to more than two or three ports. In order to service a broad spectrum of destinations (including destinations within the present-day park), several ships, most of which were based in Seward, carried passengers and freight. The S.S. Starr, owned by the San Juan Fishing and Packing Company (which operated a Seward cannery from 1917 to 1930), provided service to the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian Islands, with occasional stops in Cook Inlet and Kodiak Island, from 1921 to 1938. [22] In 1923, Seward-based guide Charles Emsweiler began serving Nuka Bay with the gasboat May; in 1925 he still served the area with the gasboat Chase. [23] In 1927, Capt. Heinie Berger commenced serving the area with the motor ship Discoverer. He provided service to Nuka Bay and Cook Inlet for the next two years. [24]

|

| The steamer Starr was another fixture along the southern Kenai coast, in Cook Inlet, and points west during the early twentieth century. Neville Public Museum, photo 5671.11. |

Berger discontinued service to Nuka Bay after the 1928 season, but by the following summer Capt. Pete Sather (known to locals as "Herring Pete") was offering twice-monthly service to the bay. During the early and mid-1930s he and his gas boat Rolfh operated as the Nuka Bay Transportation Company, and from the late 1920s through the 1940s he offered the only consistently-available passenger, freight, and mail service between Seward and Nuka Bay. [25] Berger, with the Discoverer and a sister ship, the Kasilof, continued to provide occasional service to Cook Inlet points until World War II, and several competitors also provided service during this time. When the war began, however, some of the Cook Inlet fleet was commandeered for war purposes. [26] After the war, the increasing popularity of aviation and the completion of highways connecting Anchorage with the various Kenai Peninsula communities diminished the demand for such services. In addition to these common-carrier vessels, commercial fishing boats–particularly those plying the waters between Prince William Sound and Kachemak Bay–sailed along the Kenai Peninsula's southern coast on a fairly consistent basis beginning in the 1920s, perhaps earlier. [27]

Two primary shipping lanes, both of which had been described by 1910 in the Alaska Coast Pilot Notes, followed the Kenai coastline for those who traveled between Seward and Cook Inlet ports. The larger craft–the Admiral Line ships, Alaska Steamship vessels, and others who did not need to make way stops–left Resurrection Bay and headed south past the Chiswell Islands. They then turned right; some passed between Lone Rock and the more distant Seal Rocks, while others continued beyond Seal Rocks before turning. They then paralleled the coastline, passing to the south of the Pye Islands and Nuka Island, and circled around the southwestern tip of the peninsula after passing between the Chugach and Barren Islands.

Smaller boats proceeding between Seward and Cook Inlet stayed closer to the coastline. These boats, after leaving Resurrection Bay, typically turned right immediately after passing Aialik Cape. They then used one of two passes to navigate through the Harbor Island-Chiswell Island group. Some mariners maneuvered through a passageway that lay just north of Beehive Island, while others used the pass that lay immediately south of Harbor Island. Boats then proceeded through fairly open sea to McArthur Pass (a narrow sea lane between Ragged Island, the northernmost of the Pye Islands, and the mainland). After crossing Nuka Bay, boats maneuvered through Nuka Passage and continued south to Gore Point. [28]

Establishing a Network of Navigation

Aids

Prior to 1900, the southern Kenai coast had been imperfectly mapped; what was known about the coastal topography, in fact, was virtually unchanged from what had been provided by Russian skipper Illarion Arkhimandritov, who had surveyed the outer Kenai coast during the 1840s. The founding of Seward and the consequent railroad construction activity, however, created a demand for navigational information by those who sailed in and out of the new port.

As noted in Chapter 1, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey conducted a hydrographic and topographic survey of the coastline from the Barren Islands (at the mouth of Cook Inlet) to the Chiswell Islands during the summer of 1906. The Nuka Bay coast was surveyed from August 26 to August 31 of that year. [29] Six years later, a USC&GS boat returned to the area, and shortly afterward the agency published a nautical chart for Aialik Bay. [30] Mariners appreciated the improved charts; in addition, increasingly detailed Coast Pilot editions were published in both 1910 and 1916. Even so, mariners remained worried because of the lack of navigation aids.

Resurrection Bay was widely considered to be the finest anchorage along the southern Kenai coast. Entering the bay, however, could be fraught with danger. Toward the north end of the bay, Caines Head jutted out along the west side, and the shore north of Thumb Cove presented an additional danger on the bay's east side. To those entering the bay from the southwest, few islands or other impediments hampered ship progress. Most traffic, however, came from the east or southeast, and ships from that direction faced three steep protrusions: Renard (Fox) Island, Hive Island, and Rugged Island. The passage between Renard Island (the northernmost of the three) and the bay's eastern shoreline was considered narrow and impracticable. Mariners, therefore, navigated through one of the two passages that separated the islands, most choosing the passage between Renard and Hive islands. A preponderance of fog and rough waters, however, made the passage often unsafe. Complicating the situation was a fourth island, Barwell Island, at the bay's eastern entrance. Though smaller than the other islands, Barwell lay close to the prevailing navigation lanes and also worried those who sailed into the bay.

In order to provide a suitable navigation aid, Alaskan officials pressed Washington for help. Beginning in 1904, Governor John G. Brady, with the assistance of Alaska Central Railroad officials and local mariners, lobbied Congress for a lighthouse at the entrance to Resurrection Bay. During the three decades that followed, these requests were made many times. The U.S. Light-House Board, recognizing that the new railroad substantially increased area marine traffic, generally concurred with these requests; one official noted that "the need for a lighthouse and fog signal ... was imperative." Ship captains serving Seward also lobbied for a lighthouse. Congress, however, provided few funds to the Light-House Board, and although repeated requests for a lighthouse were made over the years (the last known request was in 1935), Congress never authorized such a project. Instead, Congress opted to fund less costly navigation aids such as beacons and buoys. [31]

In 1910, the U.S. Bureau of Lighthouses (which was then part of the Commerce and Labor Department) acted to ease access into the bay when it established an acetylene light atop Caines Head. [32] Four years later the bureau, now part of the new Commerce Department and with access to more funding, placed additional lights on Pilot Rock (at the southwestern entrance to the bay) and the north end of Rugged Island. Then, in June 1916, the increase in vessel traffic brought about by the construction of the government railroad resulted in the installation of a light at Seal Rocks, located five miles south of the Chiswell Islands.

Each of these acetylene lights, as noted on a U.S. Lighthouse Service specification sheet, was similar. The layout was as follows:

The lantern is mounted on top of a wooden accumulator house, painted white, the dimensions of which are 4' by 4' in plan and about 6 feet 6 inches in height. The house is erected on a concrete foundation having an average depth of 17 inches.

These lanterns typically flashed a white light every 3 to 6 seconds and had a candlepower ranging from 130 to 310. The cost of construction materials ranged from $1000 to $2000; annual maintenance costs ranged from $30 to $50. [33]

No further lights were added in the area until the mid-1920s, when a request was made to install a light on Hive Island in Resurrection Bay. A decade earlier, officials had considered constructing a light either here or on nearby Renard Island, because the primary shipping lane for traffic to and from Seattle was located between them. However, the officials had found it "impracticable to place a light on either of these two islands in such a position that it would be favorably located for guiding vessels through the passage." But in 1923, the agency reconsidered the idea, and the following summer it installed a light on the north side of Hive Island. At the same time, it eliminated the decade-old light on Rugged Island, the location of which was ill suited to either westbound or eastbound traffic leaving Resurrection Bay. Also installed in 1924 was a so-called gas and whistling buoy in the waters just south of Barwell Island. (Barwell was another location that had been proposed–and rejected–as a site for an acetylene light.) [34] The precipitous topography of the island, and the frequent fogs that surrounded it, resulted in the establishment of a sea-level buoy rather than a light perched atop a high rock.

During the 1930s, two more navigation aids were established. In 1934, an acetylene light was installed on the north side of McArthur Pass; it was the only navigation aid established in present-day Kenai Fjords National Park. Four years later, a number of Alaska Steamship Company ships' officers petitioned the Lighthouse Service for an acetylene light on the bluff just north of Thumb Cove. That request was granted, and the light was installed in September 1938.

During the past 60 years, several changes have been made to Seward area navigation aids. The buoy near Barwell Island was replaced by "a light 412 feet above the water ... shown from a small white house" during the 1930s; then, in the late 1950s or early 1960s, the light was removed. A light was re-installed on Rugged Island in 1956 or 1957; and throughout the area, the wooden houses that previously encased the lights were largely replaced by diamond-shaped dayboards during the 1960s and 1970s. [35]

In February 1921, the U.S. General Land Office established lighthouse reservations for the existing area lights. These included sites at Caines Head, Pilot Rock, and Seal Rocks. Lighthouse reservations were also inexplicably established for Barwell Island and Hive Island, even though neither location possessed a light at that time. As a further irony, the GLO in May 1925 created a reservation at Rugged Island, even though its light had been removed the year before. All six of these lighthouse reserves, which ranged in size from a single acre (for Pilot Rock) to 600 acres (for Rugged Island), remained in effect until November 1965, when at the State of Alaska's behest reservations were eliminated on Barwell, Hive, and Rugged islands. The Caines Head reservation was revoked in June 1968 for similar reasons. Lighthouse reservations remain at the other two sites. [36]

As noted above, the only navigation aid established in the park was the McArthur Pass light, installed in 1934. Lights were not installed elsewhere along the coast, primarily because few of the ships that plied the route between Seward and Cook Inlet stayed close to the coast. Those that did sail close to the fjords and headlands were smaller craft, owned by individuals rather than corporations. When accidents did occur, therefore, they were less likely to result in pressure for navigational improvements than in a higher-volume traffic situation.

The Coast and Geodetic Survey, of which the Bureau of Lighthouses was one agency, regularly maintained its network of navigation lights along the Alaskan coast. Scattered references in the Seward Gateway indicate that the various Seward-area lights were visited and serviced on a fairly regular basis, usually by the lighthouse tender Cedar. On occasion, such as during the summers of 1930 and 1931, Coast and Geodetic Survey ships were based in Seward for extended periods. [37]

The waters along this stretch of coastline are fabled for their storminess. Given that situation, the number of accidents over the years has been few indeed. On February 4, 1946, the S.S. Yukon of the Alaska Steamship Company foundered on the rocks of Cape Fairfield (on the west side of Johnstone Bay), 30 miles southeast of Seward. More than 500 passengers were aboard her when the ship hit the rocks and began taking on water. Miraculously, only eleven lives were lost. [38]

In the waters southwest of Seward, historical accounts tell of at least four parties local residents (either hunters or fishermen) who sailed off, never to be seen again. The most notable of these incidents resulted in the disappearance of "Herring Pete" Sather, who was lost and presumed drowned in late August of 1961. [39] Others had their boats wrecked in storms and were marooned on islands–sometimes for weeks–until saved by a passing vessel. [40] In recent years, the advent of radar and new boat construction materials has reduced the danger of coastal navigation to some extent; the rough seas, however, still endanger many who venture into these waters.

Roads and Road Proposals

Within a few years of its founding, Seward had become the Kenai Peninsula's largest town, and although Seward was built as a railroad town, its citizens demanded roads as well. Seward development interests began to lobby for a road network connecting the port with its hinterland, recognizing that a well-developed road system emanating from Seward ensured the town's commercial hegemony.

To some extent, a road network had been established before the town had been founded. The Hope and Sunrise areas, the site of a minor gold rush during the early to mid-1890s, was largely inaccessible by water; ice closed Cook Inlet during the winter, and during the summer the mud flats and the enormous tidal range made access difficult. Land access from the east was similarly difficult because Portage Pass was surrounded by a dangerous snowfield. As a result, miners hoping to access an ice-free port headed south to Resurrection Bay. They cut a pack trail from Sunrise to the foot of Kenai Lake. South of the lake, a trail led south to Salmon Lake (Bear Lake). Between there and the head of Resurrection Bay, a California mining company opened up a road to the head of Resurrection Bay "at the expense of a great deal of time and labor." The Mendenhall party that traveled north from Resurrection Bay in May 1898, however, found that the mining company's route soon "developed into a very poor road;" the road (and the survey party) crossed Salmon Creek several times on their way north. [41]

Topography and the existing wagon road suggested that the first Seward-area trunk road would parallel the Alaska Central tracks. In 1907, local residents and the newly formed Alaska Road Commission (ARC) pooled their efforts and completed a seven-mile road from Seward north to the agricultural settlement of Bear Lake. The ARC, in those early days, expended few funds outside of the Richardson Highway corridor and the Fairbanks and Nome mining areas. Even so, the commission in 1912 funded a six-mile extension to the Snow River. That road quickly deteriorated, however, and in 1916 the ARC began a new 5-mile road north from Seward that paralleled the railroad tracks. In 1920, Seward-area roads received a shot in the arm because of an agreement that transferred road administration to the Bureau of Public Roads, the agency in charge of National Forest roads. Perhaps as a result of the new funding source, the road was gradually extended north, and in November 1923 the road was finally completed to the southern end of Kenai Lake. [42]

During the same period that the Seward-Kenai Lake road was being built, construction was taking place at the north end of the Kenai Peninsula that would affect the future of roadbuilding in what is now Kenai Fjords National Park. In the summer of 1907, the ARC improved upon the decade-old pack trail and built a 37-mile wagon road that connected Sunrise with the Alaska Central Railroad. That wagon road followed up the Sixmile Creek drainage to its confluence with the creek's East Fork. It then headed up that fork and continued on into the Bench Creek drainage to the Johnson Creek Summit. South of the summit, the trail continued until it reached the railroad right-of-way at Milepost 34, at the northeastern end of Upper Trail Lake. [43]

The Sunrise road remained the only other ARC-sponsored road on the Peninsula for the next several years. But in 1909, the ARC constructed a 14.5-mile sled road that ran northwest from the railroad community of Moose Pass to the Johnstown (later Gilpatricks) mining camp, which was located in the upper reaches of the Quartz Creek drainage (near today's Summit Lake Lodge). By 1911, the sled road had been extended 10 miles into the Canyon Creek drainage, and in 1913 it was extended again to the point that it joined with the 37-mile-long wagon road that had been built six years earlier. [44] By this time, traffic had begun to thin out on the road because of the decline of the Hope-Sunrise placer mines. As that trend continued, the old wagon road began to fall into disrepair. But the Moose Pass-Canyon Creek route, where mining remained active, was upgraded in 1917 to a wagon road. By the early 1920s the ARC had abandoned most of the old (1907) wagon road, but on the other route, a 1923 Seward Gateway report noted that "a fine road is now being built from Moose Pass to Hope." The new route became the only ARC-designated route between the Hope-Sunrise areas and the new government railroad. [45]

By the time the ARC was upgrading the Moose Pass-Canyon Creek sled road, several families had moved into the Cooper Landing area. In 1919, therefore, the agency stated that it planned to open up a new route from Mile 8 on the Moose Pass-Canyon Creek Road west to the Kenai River-Russian River junction. It hoped that, by doing so, it would "open up a potentially [rich?] farming country." This sled road was built in either 1920 or 1921. The agency's 1919 proposal may have been the first step in a plan to improve its 60-mile trail connecting Kenai Lake with the Cook Inlet settlement of Kenai. Soon afterward, the Bureau of Public Roads announced the proposed road plan to local residents. [46]

|

| The first road out of Seward went to Kenai Lake. It was completed in 1923. This photo, taken along the road, likely dates to 1919. The Pathfinder, May 1920, 2. |

The plan to create a sled road connecting Moose Pass and Kenai was not well received by Seward's business leaders. In their view, any roads going west to Kenai should go directly from Seward (and not via Moose Pass). Sewardites, therefore, championed a route that connected the Seward and Cooper Landing areas via the Resurrection and Russian river valleys. As noted in a February 1922 issue of the Seward Gateway, they made their voices heard in a petition sent to the Bureau of Public Roads. That petition noted that

the natural obstacles to be overcome in the construction and maintenance of this road ... are very few. There is a perfect water grade from Seward up the Resurrection River to [Upper] Russian Lake and down the Russian River to the Kenai. The cost of construction of this road to this point would be so low that the cost of a substantial bridge across the Kenai River would not bring the general cost per mile of the road up to an excessive figure.... The present road plans of the Bureau in Kenai Peninsula do not correspond with these proposed plans and in the minds of those thoroughly familiar with the country are not as feasible.

The advantages of the proposed system of roads are many and very important. The road from Mile 3-1/2 to the mouth of the Russian River in itself would work great good. It would open up a large tract of some of the finest timber on Kenai Peninsula. Russian Lake, which has been recommended as a hatchery site by the Territorial Fish Commission, would be made accessible.... In addition to this the road will pass through a country with great mineral possibilities. There are three very promising properties now in this section which are in need of such transportation as this road would afford. At Mile 18 there is the Dubriul [Dubreuil] placer property and further on there [is] the Tecklenberg and Stotko quartz properties and the Russian Pass district is considered to have many good quartz discoveries.... The extension of this proposed road [to Kenai] would open up one of the richest sections of Alaska in agricultural and grazing possibilities....

The proposed route would shorten the winter travel between the towns of Kenai and Seward about twenty-five miles.... This would mean better mail service to the towns on Cook's Inlet, and would provide a means of transportation to farmers, fishermen, fox ranchers and oil men when transportation is closed on Cook's Inlet [and] would take the hunter and tourist to the center of the greatest moose and sheep.

The request to the Bureau of Public Roads to drop its present plans and recommending the construction of the Resurrection River road is not in the way of criticism of the splendid work carried out by the Bureau but is intended as advice in the most friendly spirit.... [47]

The Bureau, in response to the petition, stated that it hoped to survey the Resurrection River route in the summer of 1922. The survey apparently took place as promised, but the agency's position toward proposed road locations did not change. The Bureau, in fact, was squarely against Seward's plan because such a road threatened to divert traffic away from the railroad. With the government now operating a subsidized railroad, all federal agencies acted in concert to minimize the line's losses. As stated in an ARC annual report, "an especial effort has been made within this [southwestern] district to furnish adequate roads, sled roads or trail to all points of development in order that traffic may be developed for the Alaska Railroad." [48] Consistent with that policy, the Bureau in 1924 began upgrading and improving the Moose Pass-Kenai trail into a widened, improved sled road, a task that took the Bureau and the Alaska Road Commission portions of the next three seasons. By the advent of World War II, the route between Cooper Landing and Moose Pass had been improved from a sled road to a wagon road. [49]

The road builders, however, did not entirely ignore the Resurrection River valley. In early 1923, ARC Superintendent Anton Eide announced, as part of the summer's work plan, that the agency would work on a sled trail connecting Seward and Kenai, the work to be paid for with territorial funds. (An ad hoc trail already existed along portions of the route because, as noted above, several mining claims were located in the upper Resurrection River valley.) The agency began graveling portions of the route that summer, but it is not known how much work was completed. ARC maps dating from the 1920s and 1930s show that a designated trail, suitable for dog teams, wound along the Resurrection River-Russian River route. The agency, however, ignored the trail in its annual reports, and the low levels of activity in the valley suggest that the trail had faded back into the forest before World War II. [50]

As noted above, a wagon road connecting Moose Pass with the old Sunrise mining camp had been completed in 1921; two years later, a road was completed connecting Seward with Kenai Lake. As soon as the Seward-Kenai Lake road was completed, Seward citizens began to demand that the various road building authorities construct a seven-mile-long "missing link" connecting the Kenai Lake road terminus with Moose Pass. But steep topography along the Kenai Lake shoreline, a lack of funds, and the ARC's attitude toward roads that competed against the railroad meant that the "missing link" was not completed until 1938. [51]

The remainder of the Kenai Peninsula's primary road network was not completed until the decade that followed World War II. In 1946, the peninsula road system was the same as it had been in 1938; it consisted of a gravel road extending northward from Seward to Hope, and a branch road reached westward to Quartz Creek to the Kenai River-Russian River confluence. But construction beginning that June pushed the road west from the Russian River, and by June 1947 a "pioneer road" had been roughed through to Kenai. The extension of the Sterling Highway from Kenai south to Homer was put through in rough form in December 1949 and completed to ARC standards in 1950. (The route was named for Hawley Sterling, a longtime road-commission superintendent, who had died in September 1948.) Plans were also made to construct a road from Moose Pass north to Anchorage. A route survey had been completed in 1945, road construction south from Anchorage began in 1948, and during fiscal year 1949, bids were let to construct a road between the Anchorage area and the Canyon Creek-Sixmile Creek confluence (today's Hope Junction). Work on that project began during the summer of 1949, and a road linking the Kenai Peninsula and Anchorage was completed and dedicated in October 1951. [52] No intercity roads have been built on the Kenai since that time.

Although Sewardites failed in their 1922 attempt to have a road constructed up the Resurrection River valley to the mouth of the Russian River, they continued to press authorities to have the road built. Their second attempt took place in the fall of 1925, when the local press reported that

the proposed Resurrection river road to the lower Kenai peninsula regions was the main topic of business confronting the local Chamber of Commerce at its regular weekly meeting.... All members were pledged to get behind the movement and individually write letters to those in authority advocating the construction of the road. Residents of the Kenai district have sent in petitions for the road and it is confidently believed that with united effort it will be constructed. [53]

Undercutting the efforts of road boosters, however, was the slow construction and improvement of a route headed westward from the Moose Pass railroad station. By the early 1940s, a government report noted that the existence of a good road from Moose Pass to Cooper Landing obviated the need for a route up the Resurrection River valley. [54]

In 1957, perhaps in response to the new Swanson River oil discoveries (see Chapter 10), Seward citizens and the Chamber of Commerce made a renewed effort for such a road. They argued that constructing such a road would shorten the distance between Seward and the communities of the western Kenai and relieve some of the traffic on the Anchorage-Kenai highway. In 1959, the advent of statehood raised hopes that the new, more independent government would move to construct the road. Neither of these efforts, however, moved highway department officials to seriously consider a road in the Resurrection-Russian River corridor. [55]

In 1967, the City of Seward issued a Comprehensive Development Plan that "strongly recommended" a road from Seward to Cooper Landing. The document noted that the road would serve three purposes: provide a more direct route between Seward and the western Kenai population centers, open up lands for recreation use, and "provide an alternate tourist route through spectacular country." [56] By this time, Herman Leirer and other local citizens (as noted in Chapter 10) had already begun pioneering a road between Seward Highway and "Resurrection Glacier" (today's Exit Glacier). Lehrer's goal was a recreational road that would provide a scenic diversion for tourists; he had no interest in going farther up the Resurrection River valley. [57]

In its 1973-74 comprehensive plan, the Kenai Peninsula Borough reiterated the need for such a road; the Alaska Department of Highways also recommended such a road during hearings held in April 1974 by the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission. [58] Those plans, however, were not implemented. Since that time, the likelihood that this road will be built has significantly decreased, due both to the establishment of Kenai Fjords National Park and because of the Forest Service's decision, in the early 1980s, to construct a recreation trail through the proposed road corridor.

The rugged topography typical of the southern Kenai Peninsula, and the existence of the Harding and other nearby icefields, have precluded serious proposals for any other long-distance transportation routes in the vicinity of Kenai Fjords National Park. Those factors, however, did not prevent two men from lobbying the Alaska Road Commission for a trail connecting Seldovia with the head of Nuka Bay. That request, in November 1933, met with a blunt, unambiguous denial. ARC official Hawley Sterling told the petitioners that the trail was "neither feasible nor practical or that it would ever be used as a through trail." A road was later built from Seldovia southeast to Rocky and Windy bays, but no serious, long-distance road or trail proposals have been located in the Nuka Bay vicinity or elsewhere in the present park. [59]

Aviation Facility Development

Aviation came of age in Alaska during the 1920s, an era dominated by bush pilots such as Noel Wien, Russell Merrill, and Carl Ben Eielson. Communities across the territory carved out airfields. Seward, which witnessed its first airplane landing in 1925, constructed an airfield between May 1927 and May 1928. Russell Merrill, who was based in Anchorage, took several passengers on a "short flight over the bay and mountains" during the summer of 1928; that same summer, he made several other flights in and out of town with trappers, game guides and their equipment. By the end of the decade, maintained and dedicated airfields had also been laid out at Kenai, Ninilchik, and Kasilof. [60]

During the 1930s, sporadic service in and out of Seward continued. Early in the decade, service was advertised between Seward and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. In both 1933 and 1934, Art Woodley offered excursions over Seward, Resurrection Bay and the Harding Ice Field at $10 for short flights and $15 for longer ones. He charged fishermen $15 for round-trip flights to the Russian River; that flight probably ascended the Resurrection River valley. In 1937, and again in 1939, two different companies named Seward Airways set up shop. These firms lasted only a short time, however. The demand for air travel was so low that scheduled flights were not offered to or from the Kenai Peninsula until after World War II. [61]

Several civilian air carriers, serving both residents and tourists, sprang up during the postwar period. In May 1945, two area residents started the Kenai Air Service, which planned to connect Seward by air with Homer, Seldovia, Valdez, and Cordova. A year later, Safeway Airlines commenced service, offering to take passengers and freight to a variety of Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound points. And in 1949, Alaska Airlines began serving Seward as well. All three of these carriers offered flights between Seward and Homer and thus gave passengers the opportunity to view the Harding Icefield, the fjords southwest of Seward, and other areas within today's park boundaries. [62] These carriers, and others that replaced them, have continued to provide occasional service to the southern Kenai Peninsula since that time.

Two airfields have been built in the immediate vicinity of the park. In 1965, miner Don Glass constructed an airstrip along the beach at Beauty Bay and used it in conjunction with operations at the Glass and Heifner mine (see Chapter 7). The other airstrip was a small, ad hoc affair located on the right (southwest) bank of the Resurrection River approximately one-half mile below its confluence with Placer Creek. This so-called "T-grass strip" was bulldozed during the 1950s, probably by hunter Jon Andrews, Sr. By all accounts, the strip was seldom used; perhaps the only user was Mr. Andrews, who flew his Taylorcraft in and out of the area until it crash-landed at one end of the strip in 1978. Since that time, the Resurrection River has reclaimed most of the airstrip, and today most of it is no longer visible. [63]

Dams and Diversion Projects

The Kenai Fjords area, which is primarily composed of icefields, cliffs, islands and seacoast, would appear to be a poor location for dams or diversion activity. But drainage management activities have taken place at both ends of the present-day park.

At the southwestern end of the park, northwest of Nuka Bay, the Bradley River and its tributary, Kachemak Creek, emerge from the Nuka and Kachemak glaciers, respectively. For thousands of years these waters flowed into Bradley Lake, and continued down to the head of Kachemak Bay. Few paid any attention to this drainage system until the late 1940s, when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation surveyed potential Alaska dam sites. The Bureau gave the site positive reviews. Then, in January 1950, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report noted that the Bradley Lake area was one of the most favorable sites for hydroelectric development in southcentral Alaska. Four years later, Governor Frank Heintzleman ordered further study of the site. In 1955 the Corps studied the site in more detail, and at its behest, the Bureau of Land Management that August withdrew some 10,000 acres from entry. That withdrawal included much of the Bradley River drainage system. The Corps continued to gather data on the project for the remainder of the decade. [64]

|

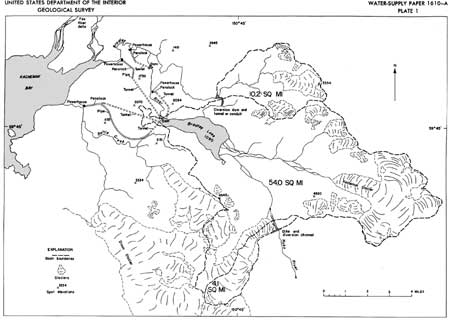

| The Bradley Lake Project as proposed in 1961. It was built from 1986 to 1991. Note the dike and diversion channel. F.A. Johnson, Waterpower Resources of the Bradley River Basin. |

By 1960, power-development advocates had become convinced that Alaska was on the verge of a power shortage; in order to avoid that scenario, they urged lawmakers to construct the Rampart Dam (on the Yukon River) to provide long-term needs and the Bradley Lake Project as an intermediate facility. [65] Based on those needs, Congress authorized Bradley Lake as part of the Flood Control Act of October 1962; it was the only hydroelectric project in Alaska to be so designated, and it remained in that position for years afterward. The following year the Army Corps applied to withdraw the land for construction purposes, and in 1966 the BLM issued public land orders granting the proposed withdrawal. By this time, however, new low-cost thermal generation had made Bradley Lake less competitive, and as a result, the project languished until the economics of hydropower once again proved advantageous. [66]

Most of the Bradley Lake project history is beyond the scope of this study, both geographically and temporally. Most of the project area is several miles away from the park boundary; as to time, the majority of the environmental studies were conducted in the late 1970s and early 1980s, project construction began in 1986, and the dam's power plant began generating electricity during the summer of 1991. [67] The high-water level of Bradley Lake, moreover, lies more than three miles away from the park boundary. What makes the dam's construction activity germane to this study, however, is that project engineers decided to divert a portion of the Nuka River's flow into the Bradley River drainage in order to maximize Bradley Lake's hydroelectric potential. The engineers learned, in the early stages of project planning, that the tongue of nearby Nuka Glacier lay astride a drainage divide, locally called Bradley Pass. Four-fifths of Nuka Glacier's outflow went into the Nuka River during low-flow periods, but during high-flow periods, four-fifths of its outflow went into Bradley River. In order to maximize the flow going into Bradley River, the engineers decided to build a 5-foot dike on the south side of Nuka Pool, which is located at Bradley Pass. The Park Service, appraised of the proposed action, approved the project in April 1985. The agency took that action because studies showed that the diversion would have a minimal effect on the spawning potential of the Nuka River's pink, coho, and chum salmon populations because other tributaries comprised the bulk of Nuka River's flow. [68]

The park's northeastern border is the site of a long-planned hydroelectric project. Soon after World War II, water-development interests recognized that the Resurrection River, a mile or so below its confluence with Paradise Creek, was a potential dam location. In March 1950, therefore, the U.S. Geological Survey declared the area a potential power site and withdrew "all land adjacent to Resurrection River and tributaries below an elevation of 500 feet" upstream from the proposed Resurrection Dam. Land in the Resurrection River valley was thus withdrawn up to a point beyond today's park boundary, near the river's confluence with Moose Creek. During the years which followed, scores of sites (including Bradley Lake, as noted above) were touted by federal agencies, the Alaska Power Authority, and local utilities; none of these entities, however, provided sustained backing for a project in the Resurrection River valley. By 1970, the high cost of developing hydroelectric potential, coupled with the unfavorable findings of more detailed studies, had made the project impractical, so the U.S. Forest Service that year recommended that the classification be revoked. That was never done, but the USGS did not protest the establishment of Kenai Fjords National Park. Today, any chance for hydroelectric development along the Resurrection River is remote. [69]

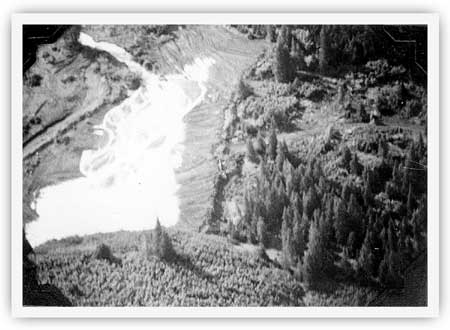

Soon after the USGS unveiled plans for a Resurrection Dam, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service undertook a small diversion project to restore historical flow levels to the Russian and Resurrection River systems. For scores if not hundreds of years, Summit Creek (just beyond the park's northern boundary) had served as the primary headwaters of the Resurrection River system. But sometime during the early 1950s–probably during the fall of 1951 or the spring of 1952–a flood sufficiently shifted the creek bed that the creek waters started flowing into the upper Russian River system. The creek, which flowed from a glacial tongue, carried a large sediment load and was "seriously polluting" the Russian River, which is a major red salmon stream. The Fish and Wildlife Service, which managed the Russian River fish runs, was concerned about the "increasingly serious" situation. In late 1957, therefore, agency workers drove a D-7 and a D-4 Caterpillar tractor to the area from Seward. They created a dike and diverted Summit Creek back to its former course. After the work was done, the agency left the larger tractor near the dike in case further repairs were needed; the smaller tractor was brought back to Seward. So far as is known, Summit Creek has remained part of the Resurrection River drainage system ever since, and the D-7 "cat" is still at the site. [70]

|

| The Summit Creek dike, taken in 1958, looking southwest. The Fish and Wildlife Service created the dike a year earlier. USF&WS, Cook Inlet Annual Management Report, 1958, 43. |

kefj/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002