|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 6:

LIVING OFF THE LAND AND SEA

Traditional Use Activities

|

| Map 6-1. Historic Sites-Fox Farming/Homesteading. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As Chapters 3 and 4 have noted, a combination of factors–disease, the lure of commercial fishing, and the encouragement of the Russian Orthodox clergy–resulted in the elimination of permanent human settlement from the present-day park during the 1880s.

Human usage of the area, however, continued. Natives from English Bay [1] and Port Graham traveled east of Gore Point where they hunted and trapped for subsistence purposes in various portions of the present park. Nuka Island was a favored location for fall hunting camps, while winter and spring hunting camps were established at sites in Nuka, Yalik, and Aialik bays. Natives frequently traveled along the entire coastline of the present-day park; Natives from Tatitlek (on the eastern side of Prince William Sound) as well as Seward and English Bay met at the hunting camps; in other instances, English Bay residents traveled to Seward to meet other hunters. [2]

The hunters left many evidences of their passing. Semi-subterranean houses (barabaras) served as shelters in Nuka Bay and perhaps elsewhere as well. In the early 1900s, trappers primarily used steel leg-hold traps. Several traditional methods were also used: a stone trap was used to take weasel and mink, and a log trap was used on otters and other larger animals. [3]

Non-Natives recorded the evidence of past trapping activities. As Josephine Tuerck (later Josephine Sather), who with her husband settled on Nuka Island in 1921, noted,

When we first came here we found all sorts of old contraptions set up in the trails and close to dens, their purpose having been to catch land otters. On the trails of the mainland and the nearby islands were decayed death-falls by the hundreds. We found little box-like houses built with sticks, in which to set steel traps for minks; all manner of spring poles; plenty of other evidence of the ingenuity of man in his effort to outwit every living thing that walked on legs.... Everything pointed to the cleverness of our predecessors on Nuka Island.

She and her husband did not trap during their first several years on the island, but in 1925, Pete and Josephine Sather set some traps for land otters on the "rocks and little islands" near Nuka Island. Their trapping thereafter, however, does not appear to have been either widespread or long lasting. [4]

Other non-Natives engaged in trapping as well. Mary Barry, the author of a multi-volume history of Seward, provides one indication of the extent of that activity:

In December 1924, Joe Schulte and Heinie Berger, pioneers of Valdez, arrived in Seward on their gasboat Arcturus while on a trapping trip. Schulte ... stayed in Seward while Berger and Captain Louis Clark took the boat to the vicinity of Nuka Bay for the trapping season. Schulte, Berger and Clark continued to go in and out of Seward that winter on trapping expeditions. [5]

During the same period, John Colberg of Seldovia and perhaps other area residents trapped up and down the southern Kenai coastline; Colberg himself trapped as far away as Rugged Island in Resurrection Bay. [6]

Hunting and trapping within the present-day park continued, to some extent, until the 1940s. It largely died out after that time. [7] Subsistence fishing, as noted below, continued for another decade because pink salmon in and around Nuka Bay supported the Sathers' fox farm. In 1951, the Fish and Wildlife Service began keeping data on Cook Inlet area subsistence fishing activities. (During the 1950s and early 1960s, it was called the "personal use fishery.") The state, when it took over management of the fisheries resource, continued the practice. Annual tabulations confirm that in the Eastern District (i.e., Resurrection Bay), subsistence fishing (primarily for red salmon) took place during most years; the most active year was 1969, when subsistence permittees caught 929 salmon. At no time from the early 1950s through the early 1970s, however, did either Territorial or State authorities receive subsistence permit applications for Outer District salmon fishing. There was, apparently, little or no interest during this period–by either Natives or non-Natives–in fishing for subsistence purposes in park waters. [8]

When the National Park Service began to get involved in the area, it issued conflicting messages about existing subsistence activities. In its December 1973 master plan, the ad hoc Alaska Planning Group stated that

at least some subsistence fishing for salmon, shellfish, and herring roe takes place in the coastal areas of the Barren, Pye, Granite and Chiswell Islands and the Aialik Peninsula [by] the people of Port Graham and English Bay. Hair seal and mountain goats are hunted in the Chiswell Islands....

But in late 1977, NPS officials declared that "there presently is no documented record of subsistence use in [the] Kenai Fjords National Park proposal, although the Interior Department is recommending the park be open to subsistence use." [9] Neither President Carter's proclamation creating Kenai Fjords National Monument in 1978, nor the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 establishing Kenai Fjords National Park, provided language that authorized hunting, trapping or other subsistence uses. Specific data concerning where trapping traditionally took place prior to the park's establishment, and usage levels within those areas, have been investigated by others [10] and will not be repeated here.

Fox Farming

The area both within and surrounding the present-day park is hostile to most forms of permanent settlement. Owing to poor soils and the scarcity of level land, the area is not conducive to agricultural, horticultural, industrial or most other activities.

Despite those restrictions, the park area has hosted a variety of activities, one of the most persistent being fox farming. Fox farming, an activity once practiced in many parts of Alaska, traces its roots to the Russian explorers. Some of the earliest explorers discovered foxes living on various of the Aleutian Islands, and by 1746, Russians were both harvesting foxes and transplanting them to other islands in the chain. To the Russians, foxes were not nearly as important as sea otters and fur seals; fox pelts were, however, sufficiently valuable that the Russians eliminated the populations of inferior fox species on several islands in order to specialize in so-called blue foxes. [11] The Russians continued to harvest wild foxes during their 125 years of commercial hegemony; during that time, hunters collected hundreds of thousands of fox skins and had them shipped to markets in Russia or China. Hunters did not deplete the islands' fox populations, and the supply was generally plentiful. The number of foxes in a given year, however, was highly variable due to a number of factors. For the same reasons, fur quality often suffered.

|

| During the 1920s and 1930s, hundreds of offshore islands, along with some mainland sites, housed fox farms. Alaska Magazine, July 1946, 9. |

In order to avoid the unpredictability and variable fur quality inherent in wild fur harvesting, and to expand the geographical range in which foxes might be grown, several entrepreneurs decided to farm foxes commercially. The first Alaska fox farm began in the Semidi Islands (southwest of Kodiak Island) in the 1880s. [12] The practice spread. By the mid-1890s, an operation had been established on Long Island, near Kodiak, and on various islands in Prince William Sound. [13] Fox farming, at this time, was a rare if not nonexistent activity south of the forty-ninth parallel.

By the turn of the century, fox farms were increasingly common in southcentral and southeastern Alaska; in 1900, 35 islands were being leased from the government. Beginning in 1903, however, fur prices bottomed out and many islands were abandoned. Prices remained low for a decade; during this early period, many raised foxes as breeding stock and began selling them to newly established fur farms in the United States. In 1913, the popularity of furs (and the prices that they garnered) started to rise. [14] For the next fifteen years fur farms–particularly those that raised blue foxes–became increasingly popular. The height of popularity was reached in 1930, when 485 Alaska fur farm licenses were issued. Though fox farming was carried on in many parts of Alaska, it was most common in the coastal areas, where salmon, harbor seals, porpoises, whales and other marine food sources were available. The best fox farming sites were small offshore islands, where pens and feed houses were largely unnecessary. [15]

On the Kenai Peninsula, the first fox farm was established on Perl Island (one of the Chugach Islands group) in 1894. By 1900, new farms had been located on Elizabeth Island (four miles west of Perl Island), on East Chugach Island, and on Yukon and Hesketh islands in Kachemak Bay. The Kachemak Bay farms were apparently successful, long-term enterprises but the Perl and Elizabeth Island operations were not. A second attempt was made to farm the island in 1915, and by 1919, both Perl and East Chugach islands were being leased as fox farms. [16]

In Resurrection Bay, several fur farm operations were active, all on appropriately named Renard (Fox) Island. Alfred and Billy Lowell established the first farm in 1901. Starting with three pairs of blue foxes, the population grew dramatically, and by September 1905, the island had more than 400 foxes. The brothers built a dwelling and three feed houses on the island. But they had a hard time selling the foxes, so they put the farm up for sale. Lacking a buyer, they soon abandoned it. In 1907, two brothers named Phillips invested in the island, hoping to grow marten there; it is unknown, however, if they did so. [17]

Nine years later, Lars Matt Olson (in partnership with Seward storeowner Thomas W. Hawkins) made another attempt to farm furs on the island. In 1915, Olson filed a location notice for the island; by year's end he was living in a cabin on the bay (so-called Northwest Harbor) at the island's northern end and was raising angora goats and blue foxes. A year later, in July 1916, he filed for a homestead entry on the island. The General Land Office quickly rejected the claim (a December 1911 executive order had withdrawn the island from settlement, along with most of the land in and around Resurrection Bay), but Olson soldiered on. He remained on the island until June 1920, when illness forced him to move Outside. The island gained fame because in August 1918, Olson invited artist Rockwell Kent and his son to live in a nearby cabin (see Chapter 10). Father and son remained on the island for more than six months; then, in 1920, the artist published a popular book about his sojourn. Entitled Wilderness, A Journal of Quiet Adventure, it was Kent's first full-length book. The book, illustrated with the artist's distinctive woodcuts, helped publicize both Alaska and Seward. [18]

Before long, others took over where Olson had left off. In 1921, Tom Tessier moved to the island; he too raised furs and remained there for the next several years. Decades later, in October 1958, William C. Justice leased the island for fur farming purposes. He apparently made no steps to either live there or raise furs, and in January 1965 his lease expired. [19]

West of today's park, fox farmers pursued their craft in Seldovia and on Passage Island (between Port Graham and English Bay), as well as on the various Chugach islands. Area fox farms continued to operate, either on islands or in pens, as late as the 1940s. [20]

North of the park, in the peninsula's interior, a number of farmers were active with pen-raised foxes. Beginning in 1914, a man named Deegan ran a fox ranch at Kenai Lake, and by 1918, F. E. Whelpley owned a fox farm in the area and partners William Kaiser and Henry Lucas ran a farm on Skilak Lake. Lucas and Kaiser kept their operation going until 1923, if not longer. During this period, two other fox farmers set up shop: Mrs. L. W. Bishop (along the Russian River) and James Paulson. In 1925, a man named Newman went into business at Kenai Lake and remained there until 1928, possibly longer. Bishop's or Newman's operations may have continued into the early 1930s, but the others faded away and no new fur farms re-emerged. [21]

The Nuka Island Fox Farm

The only fox farm within the present park boundaries, and the best known fox farming operation along the Kenai Peninsula's southern coast, was located on Nuka Island, at the southwestern edge of the present-day national park.

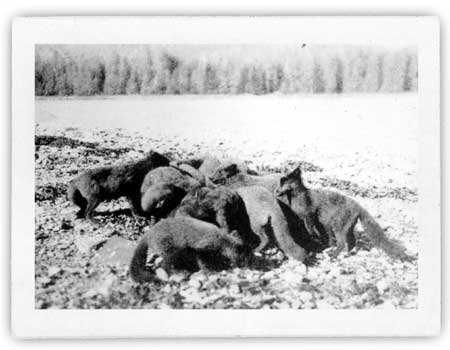

Edward Tuerck and his wife, Josephine, established the fox farm in the spring of 1921. [22] A year previously, the couple was living in Cordova when Joe and Muz Ibach arrived in town from their Middleton Island fox farm and sold furs worth $17,000. That sale, coupled with a $10,000 fur harvest a year earlier, caused a sensation in Cordova. [23] As Josephine later recalled, "the fox ranching industry became the prevailing topic of the day, and the question of where one could find an island suitable for the purpose, the main topic of discussion." Mr. Tuerck then discussed the idea with Charles Dustin, and the two set about looking for an appropriate island for raising foxes. On April 6, 1921, Tuerck chartered a boat, loaded it with lumber, and set out for the Pye Islands. He soon discovered, however, that the islands were exposed, steep and utterly lacking in a suitable harbor, so the boat continued west to Nuka Island where a "natural harbor" was located. [24] Tuerck liked the site, so he posted a location notice and helped haul the boatload of lumber ashore. They then sailed back to the copper mining community of Latouche, which was, in the recollections of Tuerck's wife, "the nearest town from which they could communicate with the Land Office in Juneau." On April 12, they notified that office. [25]

Development of the site proceeded quickly thereafter. In May, Tuerck and Dustin, acting as partners, returned to the site and began building a house. Construction of the small, rectangular residence proceeded slowly. In mid-July Tuerck's wife joined them, and within weeks the structure had been completed along with a hen house, storehouse, and a 3,000-foot water line connecting the house to a nearby creek. In early September, six pairs of blue foxes arrived, the beginnings of their fur farming operation. Soon afterward, Dustin moved to Seattle and his role in the operation became less active. [26]

The fox farm, known in business circles as the Dustin & Tuerck Fur Company, [27] appears to have been economically successful, and the fox population proliferated on the island. The foxes were given a varied diet. To save on feed costs, they were provided as many locally caught products as possible; humpback salmon was a staple, supplemented by the meat of seals, sea lions, and even whales when they could be procured. When fish and marine mammals were scarce, the foxes were fed a cooked compote of rolled oats and rolled wheat, mixed together with soaked-out fish, seal oil, and cracklings. Josephine occasionally made the foxes hotcakes and provided eggs from the nearby hen house. [28]

One of the foxes' only natural predators was the bald eagle. Mrs. Sather noted that "our island swarmed with eagles," and she quickly learned that they ate ducks, porcupines, minks, fish, and birds' eggs. Considering herself a nature lover, she deplored the eagles' dietary habits; what really angered her was the discovery of young fox hides, torn to rags, near the eagles' nests. The terms of her fur farm lease expressly forbade the killing of "any game animals or birds ... and to exercise all reasonable precaution to conserve game and wild birds on the land covered by this lease." Mrs. Sather, however, felt that "these predatory eagles were a menace to our fox-raising enterprise." Because of the perceived "menace" to the fox population, because enforcement of the fish and game laws was minimal, and because of the additional incentive of an eagle bounty–$2 for each pair of talons–she shot several hundred eagles during her stay on the island. [29]

One of the primary reasons that the couple settled on Nuka Island was that Ed Tuerck "had not been well for some time" and that "a change might be the very thing he needed." After settling on the Nuka Island, Tuerck's health initially improved. In the early summer of 1923, however, he was taken seriously ill, and on July 24 he left the island in order to get medical attention. He was examined in Anchorage and was told that his sickness–stomach cancer–was incurable. He returned to Seward, where he died on August 26. [30]

Josephine spent the following winter on the island with Edward's daughter and son-in-law. [31] She quickly concluded that she loved her home and the fox-farming lifestyle. She was, however, unable to run the business on her own, and by the following spring she was heavily in debt. She was given an offer to sell her half of the fur company, but instead vowed that she would not leave Nuka Island. So as she later noted, "Consequently there was only one thing for me to do–marry a man who took the same delight in Nature that I did, and who would be capable and willing to take care of the fur business." That man was Captain Peter P. Sather, "a man whom [Edward] and I had always had the highest respect and regard." [32] Seward's U.S. Commissioner wed the two on May 5, 1924. Their union, a marriage of convenience, continued until his death in the early 1960s. [33]

|

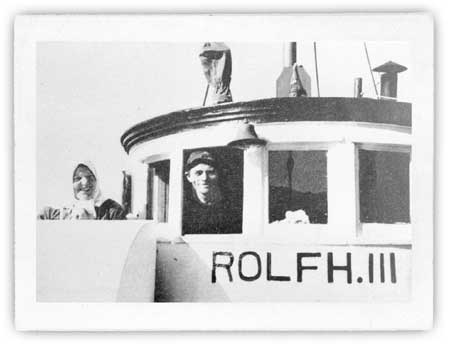

| Pete and Josephine Sather on board their gas boat, the Rolfh III. Alaska Sportsman, September 1946, 19. |

Much has been written about "Herring Pete" Sather over the years, and many old-timers from Seward, Seldovia, Homer and vicinity fondly recall his personality and eccentricities. (One reporter hailed him, late in life, as a man "known the length and breadth of the rugged 49th state as a man who can't stand dry land." [34]) Most remember him as warm-hearted and generous, if a bit quirky. Because he and his wife were the only long-term permanent residents who lived between Caines Head and Portlock during the twentieth century, many recognize that the two were the most important single elements unifying human activity in the fjords country from the mid-1920s until the early 1960s. Pete was well known because he was a jack-of-all-trades. He owned and worked at two different Nuka Bay mines; he was a commercial halibut fisherman and caught salmon for both commercial and subsistence purposes; he transported miners, hunters, sightseers, mail, and freight between Seward and Nuka Bay; and he, along with Josephine, operated a successful fox farm. Because the couple was involved in so many activities, many consider them the pre-eminent historical figures associated with Kenai Fjords National Park.

|

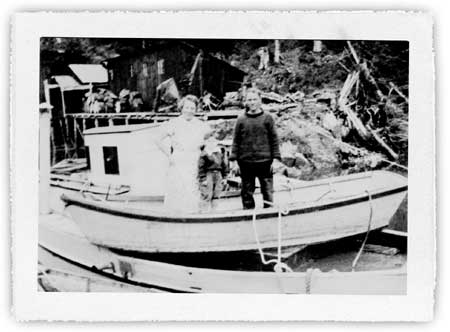

| The Sathers, and a young friend, as they appeared in the late 1930s. Hans Hanson photo, from Alaska Magazine, July 1974, 29. |

Two activities quickly followed the Sathers' marriage; one related to business rights, the other to site development. In July 1925, Josephine Sather acquired the other half of the fur farming business from her partners. Charles Dustin, now living in Seattle, and Robert Mooney, a Kennicott resident, were apparently no longer interested in remaining active in the operation. [35] So in exchange for 40 pairs of foxes, they gave up their interest in fox farming and also agreed to repay a debt that the Tuercks owed to a Seward merchant. Shortly thereafter, in July 1926, Congress passed a fur farm leasing act, an action that finally allowed Mrs. Sather, and fur farmers throughout the territory, the opportunity to gain a legal right to their properties. For years thereafter, she retained her fox farm lease by paying $50 per year to the General Land Office. Although Alaska Game Commission and other government records show Pete as the fox farm's operator, Josephine remained the sole possessor of the fox farm lease. [36]

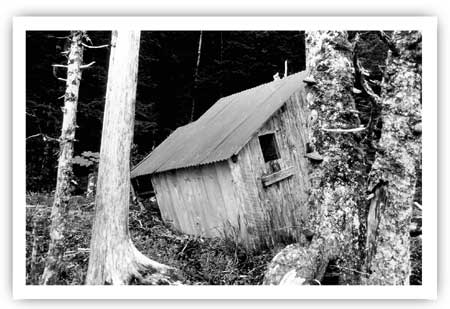

During the mid- to late 1920s, Pete made a number of improvements to the fox farming operation. He added a number of rooms to their residence, including a bedroom, pantry, woodshed, sun room, and combination skinning room and bathroom. In addition, he constructed a cookhouse for preparing fox feed; a 16' x 32' breeder shed; a machine shop; and several cement tanks, for salting fish. He also built 32 6' x 8' feed houses, [37] each complete with a tunnel and trap door. The feed houses were scattered all over the island, each within easy walking distance of the ocean in order to allow easy access. And to improve boat access to his residence, he built a dock and float. Pete was no carpenter; as Josephine once wrote, "Pete is not long on patience when it comes to building, and never takes the pains to line one up just right before he starts. Consequently not a piece from beginning to end fits as it should." Despite that characteristic, much of his handiwork from that period has remained to the present day. [38]

|

| "Herring Pete" and Josephine Sather built several dozen feed houses on Nuka Island. Several of these structures may still stand. M. Woodbridge Williams photo, NPS/Alaska Area Office print file. |

The operation, and the Alaska fur farm industry, showed increasingly bright prospects during the 1920s, and the number of Alaska fur farms increased from 146, after the 1922 season, to 262 in 1926. The year 1929 was particularly prosperous with high pelt prices, unprecedented production levels and a flamboyant fur market; Alaska had 384 fur farms that year. On October 29, however, "Black Tuesday" on Wall Street ushered in the Great Depression, a period that had a catastrophic effect on the industry because fur garments were luxury items. Within a year after the stock market crash, the value of Alaskan fur exports had experienced a sharp decline; blue fox pelt prices, for example, dropped from $99 to $62. Soon afterward, the bottom dropped out of the market: pelt prices fell to $28 in 1931 and to $21 in 1932. One Kachemak Bay fur farmer, Steve Zawistowski, recalled that in 1930 he received an average of $100 per pelt. But by 1932, similar pelts brought only $11–a price, Zawistowski wryly noted, "that put us out of business right there." Unfavorable market conditions forced many Alaskan fur farmers out of business. By 1933, only 310 fur farms remained in operation, compared with 476 farms in 1930. [39]

The remainder of the decade brought mixed fortunes to the fur farming industry. In 1933, the price of blue fox pelts rose for the first time since 1929, but they remained well below the prices that had been garnered during the 1920s, and they never again rose above $35. Even so, blue fox production remained as high as it had been during a decade earlier. Depressed prices forced many other fox farmers to abandon the business, and by 1939 only 220 farms remained in the territory. [40] The poor price structure meant less revenue for the Sathers, along with other Alaskan fox farmers. The Sathers, however, were able to remain in business throughout the decade. As noted in other chapters, "Herring Pete" was able to supplement his fur farming income by transporting people, mail, and freight between Seward and the various Nuka Bay mines, and by engaging in commercial fishing as well.

The decades that followed were even harder on fox farmers than the 1930s had been. The advent of World War II reduced the demand for furs and other luxuries, and the postwar years brought increased economic opportunities that lured fox farmers into other lines of work. Consumers, moreover, increasingly preferred coats made of mink rather than blue fox, so pelt prices remained low. As a result of these and other factors, the number of Alaska fox farms continued to decline from 220 in 1939 to 87 in 1944; to 62 in 1947; to 24 in 1950; to 15 in 1957; and to only 4 in 1966. [41]

|

| The Sather family homestead, as it looked in 1938. Alaska Sportsman, October 1946, 21. |

Despite these increasingly gloomy trends, the Sather fox farm continued to operate, a hardy survivor in an industry that was quickly becoming a shadow of its former self. In its 1947 edition, the U.S. Coast Pilot warned passing ships that "Nuka Island is used as a fox farm. Numerous ‘No Trespassing' signs are on prominent points and islands along the northern and western shores of the island." Soon afterward, however, the Sathers stopped renewing their annual fur farm license, and by 1954 the Coast Pilot described Nuka Island as containing "the remaining buildings of what was once a fox farm." Even so, Pete and Josephine continued to live at their Nuka Island residence. [42]

What happened to their foxes, now essentially valueless, is not entirely clear. For the first several years after the couple abandoned their business, Pete continued to hunt and fish for the foxes; he did this because of the couple's fondness for wildlife, foxes included. The Sathers continued to feed some foxes as late as the summer of 1961. [43] But beginning in the late 1950s, the couple may have taken a cue from various Aleutian Islands farmers and simply left most of their remaining foxes to fend for themselves. Arctic foxes, after all, have been known to survive, unattended, on large islands by scavenging the beaches and bird rookeries for food. On one of the Barren Islands, a farmer abandoned her farm in 1930; she returned seven years later to find a healthy fox population, even though poachers had been active. [44] On Nuka Island, the chances for survival were diminished because small game and rodents had long since been eliminated and because readily available marine life was scarce as well. Even so, however, a number of foxes were apparently able to adapt to the new regime; a woman who resided on the island in the early 1980s has definite recollections of foxes (and mink) on the island. [45]

During the postwar years, the Sathers continued to live at their Nuka Island home, Pete earning most of his income by fishing. By the mid-1950s, as noted above, the continuing decline in fur prices caused the couple to lose their enthusiasm for fur farming. Because Pete was off fishing for long periods, Josephine, now in her mid- to late 70s, became concerned about her isolation. In August 1959 she moved to Seattle, only to move back again the following spring. [46] Then, in late August 1961, tragedy struck. On the way back to Nuka Island from a trip to Seward, Pete's boat was lost in a storm, and he was never seen again. The following July, Josephine left the island, returned to her home town of Ellmau, Austria, and began living with her niece. She died there, at the age of 82, on October 13, 1964. [47]

After Josephine left the island, a family named Johnson moved there; exactly who lived there, however, is under some dispute. One source notes that Chuck and Sherry Johnson bought the lease. A longtime resident, however, states that Mike Johnson was living at the site before the March 1964 earthquake, and land records show that Ms. Billie June Wiles Johnson obtained a ten-year fur farm lease beginning on April 1, 1963. [48] The Johnsons, moreover, were not the only ones to live on the island. In 1966, the Suddath family (of Seward) lived there, and others apparently did as well between the mid-1960s and the early 1970s. [49]

In July 1966, the State of Alaska applied for title to Nuka Island along with adjacent acreage on the mainland, all of which was federally owned at that time. The BLM reacted to the state's 75,521-acre application, which was part of its 104 million-acre statehood allotment, by incrementally reducing the size of Billie Johnson's lease. In 1973, Johnson applied to the BLM for a new lease, which was set to expire on September 1 of that year. By that time, however, the state's application was well underway, and a BLM official informed her that her lease would be canceled once the agency gave tentative approval to the state's application. Johnson fought the ruling, but on October 1, 1973 the agency issued a decision denying the lease renewal. [50] Johnson was invited to apply to the state's Division of Lands for a new lease. Either she or her husband apparently applied for, and were granted, a mining lease. That lease remained in effect for the remainder of the decade. [51]

|

| Photo of the Sather homestead, c. 1985. McMahan and Holmes, Report, January 1987, 36. |

Homesteading

Developers over the years have long considered the Kenai Peninsula as an agricultural area. Russian colonists, as noted in Chapter 3, planted crops in various sites along the eastern side of Cook Inlet; then, during the 1920s and 1930s, homesteaders trickled into the area surrounding Kenai, Homer and other coastal communities. [52] Homesteaders settled in the Seward area as well during the first two decades of the twentieth century, and by 1915 an uneven line of homesteads connected Seward and Bear Lake (seven miles to the north). No homesteads, however, were located more than two miles west of the Alaska Central tracks; thus all were located several miles east of the present park boundary. [53] The rest of the peninsula's southern coast, moreover, was inimical to agricultural settlement because of poor soil development and a paucity of level land.

Despite those drawbacks, various would-be settlers have been attracted to the southern Kenai Peninsula coast during the twentieth century. Few of these people attempted to homestead land in the narrow sense; because the area was not agricultural, it attracted people that were drawn to the area's remoteness and isolation. Those were the same qualities, however, that proved inimical to long-term settlement.

The first area homesteaders were "moonshiners," who settled in the area shortly after Prohibition became law in Alaska. On a national level, the eighteenth amendment to the U.S. constitution, which mandated Prohibition, was submitted to the states for ratification in late 1917, and it became effective in January 1920. But in Alaska, action against the liquor industry proceeded more quickly. An act of the 1915 legislature demanded a vote "as to Whether or Not Intoxicating Liquors Shall Be Manufactured or Sold in the Territory." In the November 1916 general election, Alaskans approved this measure by almost a 2-to-1 vote. Alaska's congressional delegate, James Wickersham, responded to the vote by introducing a bill in the House of Representatives in January 1917 that implemented its provisions. The bill quickly passed Congress, and on February 14, President Woodrow Wilson signed the so-called "Alaska Bone Dry Law." This law, which was considered drastic even by the standards of Prohibition advocates, became effective on January 1, 1918. It remained the law of the land in Alaska until April 13, 1934, more than four months after Prohibition was repealed on the national level. [54] It should be noted that the sentiments of Seward citizens largely paralleled those in the rest of the territory; in April 1915 and again in June 1916, city-wide votes showed the residents were strongly in favor of allowing liquor licenses to be issued, but in the November 1916 election, Seward elected to go "dry" by a lopsided 271 to 160 vote. Seldovia voters also supported Prohibition. [55]

Alaskans, along with other westerners, earnestly hoped that Prohibition would succeed in eliminating a host of social ills tied to liquor consumption. Alaskan officials, most of whom were "dry" advocates, were initially optimistic that the Bone Dry Law would be successfully implemented and enforced. It was not long, however, before Alaskans began to honor the law in the breach. In order to obtain alcoholic beverages, smuggling and the manufacture of "moonshine" became increasingly popular.

Both of these activities took place in the area surrounding the present-day park. As noted in the records of the magistrate as well as in local newspaper articles, smuggling (and occasional arrests) took place through the Port of Seward. The making of moonshine was more widespread. Several incidents of liquor manufacture were reported inside of Seward residences–one part of town was known for years afterward as "homebrew alley"–but others took place outside of town. Charles Emsweiler, a Seward police patrolman, maintained some stills of his own down the bay; Gus Wyman, a local old-timer, set up a distilling factory at Caines Head. [56] Another party set up a still near the mouth of Fourth of July Creek. Renard Island resident Rockwell Kent noted that in early 1919, a gasoline boat just offshore was "doubtless out dragging somewhere for a cache of whiskey. Lots of whiskey has been sunk in the bay." [57]

"Moonshine" whiskey was reportedly manufactured in several places in or near the present park. One such site was on the western side of Nuka Island. Three men–George Hogg, [58] "Smokehouse Mike," and a man known only as Jack–lived at a camp about two miles south of Herring Pete's Cove. As Josephine Sather noted in a 1946 article, [the camp] "was in a hidden nook, and a thirty by thirty-six warehouse stood on a grassy bank. A sixty-foot gas boat, resting on the mud at low tide, was tied to the dock." Elsewhere on the island, at an unknown location, was located "a building about twenty feet square." Inside the building, "standing on benches three feet high all around the walls were fifty-gallon mash barrels.... In one corner stood a thirty-gallon still, going full blast. The ‘mountain dew' was running in a crystal-clear stream the thickness of a good-sized sewing needle." The operation, which may have begun as early as 1918, was shut down in 1921 at the Tuercks' request. The trio had no legal claim to the island; besides, both Edward and Josephine were teetotalers. [59]

Because the shorelines of the present park were both isolated and unpopulated, moonshiners often visited the area on clandestine business. Longtime Sewardites Bart Stanton and Virginia Darling, for example, recall that bootleggers worked out of Nuka Bay during Prohibition days; Stanton worked at a Nuka Bay mine during the 1930s, and Ms. Darling, who has long been associated with the Brown and Hawkins store, remembers selling materials for stills that were being assembled in that area. Another longtime resident, John Paulsteiner, noted that "Nuka Bay was also a favored location" for moonshine stills and that Sam Romack and his brother, Tony Parich, "had stills in a good part of the Peninsula." Concrete evidence of area activity was revealed during the 1960s, when geologist Donald Richter found a 30-gallen whiskey still in a secluded cove in Beauty Bay. [60]

So far as is known, only one man lived in the present-day park prior to World War II who was neither a mineral claimant nor a fur-farm lessee. Bob Evans, a veteran of World War I, built and lived in a cabin near McCarty Lagoon. Josephine Sather recalled that "his poor body was a wreck;" he had cancer of the throat, bad lungs, and impaired hearing. Even so, he worked in the area for years. He first did mining assessment work for others; he later hunted seals and finally did some prospecting on his own. The setting for his cabin was scenic, but because it was located near the face of McCarty Glacier, [61] tides and drift ice often made access impossible. The lack of access may have had tragic consequences; Evans shot himself in May 1941, apparently from depression brought on by complications after a fairly minor injury. [62] The cabin was never occupied again. [63]

After the war, others came to the southern coastline hoping to settle. Most of those who arrived prior to 1960 stuck it out long enough to overcome the obstacles to land ownership. Those who came afterward, however, remained for only a short time and were largely unsuccessful in their pursuit; they were driven out by the weather, by poor economic opportunities, or by prior, conflicting land claims.

The first person during the postwar period to announce an intention to settle within the boundaries of the present park was Alma Dodge, a mixed-blood Aleut. Dodge and her husband Jack lived in Seward during the 1950s; beginning in 1956, they apparently began to visit Harris Peninsula, and showed a particular interest in a stretch of coastline just west of Verdant Island. According to a friend, the couple "sought the use of this land for the abundance of wild berries and game animals, including both seal and otter for food and pelts and for the fish available in adjacent waters." Another friend noted that the Dodges "used bear, goat, seal, clams, fish and berries they brought from [the peninsula]. They also trapped otter and wolverine." [64]

Before long the couple moved to Palmer, and in late August 1968, Ms. Dodge filed for two parcels on the peninsula–one of 80 acres and another, of 40 acres, two miles to the south–in accordance with the Native Allotment Act of 1906. (The parcels contained some land that sloped gently to the shoreline, but the coastline between the two parcels was steep and uninhabitable.) She claimed, at the time, that she had just begun using the parcels (a claim that was later revised) and that she used the parcels "for subsistence purposes in the traditional Native manner." The couple built a 24-foot Quonset hut that summer on the 40-acre parcel; a cache, tent, fire pit, boat rack, fuel cache and other improvements were also constructed at the site.

The couple continued to visit the site on a regular basis until 1969, then again in 1972 and 1973, but did not return after then due to illness. They moved to Bremerton, Washington and later to Silverdale, Washington where, during the early 1980s, they conducted a spirited correspondence with BLM officials about the adequacy of their claim. BLM personnel, upon visiting the site, claimed that there was no evidence that the Dodges were entitled to ownership of the northern parcel. A 1985 survey, however, resulted in the agency reversing its decision, and in May 1988 the BLM issued a Certificate of Allotment awarding the two parcels to the claimant. Ms. Dodge, however, had died of cancer in June 1983, so the property was transferred to her estate. [65]

Another person who showed an interest in land within the present park's boundaries was Seward resident Bernard W. (Bill) Younker. A longtime seal hunter in the fjords, Younker occupied a site in early July 1957 on the east side of Aialik Bay; the site was half a mile north of Coleman Bay, near Aialik Glacier's terminal moraine. By mid-July, he had constructed an 11' x 14' one room cabin, a tent frame, and a gas and oil locker. He decided then to apply for a five-acre headquarters site, hoping to use it as a base camp from which to guide hunting parties and hunt harbor seals, both on a commercial basis. In November 1959, Younker sold his improvements to William F. Hart, Jr. of Anchorage, who intended to hunt and trap in the area. The following summer, several people used the cabin; based on that and other qualifying information, a BLM official noted in February 1963 that "Mr. Hart has earned title to the subject land." A Native protest, made in January 1967, suspended further action on the land claim, but in March 1972, just three months after passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, Hart was awarded title to the 4.86-acre parcel. [66]

|

| Hunters found harbor seals to be easy targets; if hit in the wrong place, however, the seals sank from sight. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 19. |

During the years that followed, the fjords attracted several settlers who, for one reason or another, did not remain in the area for long. In July of 1959, for example, Raymond W. Gregory of Spenard occupied a site at Bulldog Cove, just south of Bear Glacier on the west side of Resurrection Bay. A month later, Gregory applied for an 80-acre trade and manufacturing site and stated his intention of establishing a fishing lodge. But he made no improvements at the site, and his claim eventually expired. In March 1963, Ralph Grosvold, Jr. of Kodiak filed for a 135-acre Native allotment, also in Bulldog Cove. Two years earlier, however, the BLM had withdrawn 900 acres in that area for recreation and public purposes under the Act of June 14, 1926. The agency, therefore, immediately rejected his application and Grosvold made no further attempts to obtain land in the area. [67]

On January 6, 1967, the land ownership pattern of the present-day park was forever changed when the Native villages of English Bay and Port Graham laid claim to most of the southern Kenai Peninsula. Earlier, several Native entities east of the Kenai Peninsula–the Native village of Tatitlek, the Chugach Tribe, the Chugach Native Association and the Eyak Tribe–had filed a claim for millions of acres of land and water between Prince William Sound and Malaspina Glacier, and the January 6 action had the practical effect of extending that claim to the west. The Native leaders responsible for filing the huge claims made it clear that they had no intention of stopping all new developments within their claim area; village leaders in English Bay and Port Graham, in fact, noted that "We are not protesting against coal prospecting permits, small tracts and homesites." The Natives' primary concerns were the continued issuance of oil and gas leases. [68]

Despite the village leaders' conciliatory tone, the practical effect of the January 1967 Native land claim was to freeze action on existing claims until the Native lands question could be resolved. Their action also prevented the consideration of any new non-Native claims. Three people, in fact, stepped forward to claim land between January 1967 and the passage date of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (in December 1971). BLM officials thwarted each attempt. Daniel M. Pollachek of Seward, in July 1967, staked out a five-acre homesite on the south shore of Paradise Cove, at the southeastern end of Aialik Bay. That same month, Lyda A. Scott of Spenard filed for property near Hoof Point, at the east end of Ragged Island (part of the Pye Islands); she hoped to "raise animals [specifically rabbits] for fur and meat," operate a boat fuel stop, and make handicraft items. Finally, Theodore W. Jackson of Anchorage, in March 1968, hoped to establish a fishing and seal-hunting site on Granite Island. So far as is known, an array of survey stakes were the only known improvements on the three claims. [69]

Harbor Seal Harvesting Prior to

1960

The southern Kenai Peninsula coastline is generally rocky and precipitous with numerous deep-water fjords. These conditions are highly attractive to harbor seal populations, and seals are particularly drawn to areas near calving tidewater glaciers. Not surprisingly, therefore, there are "high densities" of harbor seals in Resurrection Bay, Aialik Bay, Holgate Arm, Harris Bay, the Twin Islands (near Aligo Point), McCarty Fjord, Moonlight Bay, Beauty Bay, and the west side of Nuka Island. Several hundred seals live in the vicinity of each of the area's tidewater glaciers, and a biologist in a 1976 survey counted 2,233 harbor seals in park waters. As noted in the paragraphs below, many of these areas have witnessed seal harvests over the years, but so far as is known, these harvests have had no appreciable effects on the long-term viability of harbor seal populations. [70]

During the early twentieth century, the seals in the present-day park were for the most part ignored. Natives from English Bay and Port Graham did not, as a rule, harvest seals as part of their subsistence lifestyle, and the few non-Native miners and fishermen who lived in and around the present park had little interest in them.

That situation changed in 1927, when the territorial legislature passed a bill creating a bounty for hair seals. [71] That situation grew out of a general attitude among Alaska residents, many of whom hunted or fished. Alaskans, along with Lower 48 residents at the time, drew a sharp distinction between "desirable" (edible or commercially valuable) and "undesirable" game and fish species, and few Alaskans had qualms about manipulating game or fish populations in order to increase the harvests of desirable species. As a result of those attitudes, the territorial legislature passed a law in 1915 creating a bounty on wolves, because of their effect on caribou populations. Two years later it instituted a bounty on bald eagles, because it was thought that salmon constituted a major portion of their diet. Other laws subject to bounty were coyotes (beginning in 1929), Dolly Varden trout (1933), and wolverines (1953). [72]

Agitation to pass a hair seal bounty apparently began in 1925, when a government study concluded that the diet of hair seals, which lived near the coast, was rich in salmon. (But fur seals, that inhabited deeper waters, were less prone to ingest them.) That study reinforced the attitudes of many Alaskans; one wildlife agent noted that "according to popular belief, there were anywhere up to a million sea lions and double that number of harbor seals in Alaskan waters, each one making catches of food greater than the average fisherman could produce." [73] Perhaps in response to the study, Alaska state senators John W. Dunn and Charles W. Brown (both on the Fisheries, Game and Agriculture Committee) introduced a measure on March 28, 1927 mandating a $2 bounty. On April 20, the bill unanimously passed the Senate. Soon afterward it sailed through the House, and on May 3, Governor George Parks approved the bill and it immediately went into effect. [74] The bounty was applicable for all seals harvested "adjacent to the southern coast of Alaska and east of the 152nd meridian," which included southeastern Alaska and all of south central Alaska east of Cook Inlet. In order to obtain the bounty, hunters were asked to show the face of the seal skin, including both eye holes and both ears, to any U.S. Commissioner, postmaster, or notary public. They also had to fill out a certificate showing where, when and how the animals were killed. [75]

Alaskans responded to the law with a modest degree of enthusiasm. For the next twenty years, the number of seals harvested each year seldom exceeded ten thousand per year. Several reasons accounted for the limited amount of activity. First, both seal meat and seal hides had little value. Second, the bounty was insufficient to provide a living to anyone but the most dedicated hunters. Finally, seal hunting required both a rugged, sea-going boat and a skiff, articles that most residents did not possess. As a result, a federal official noted in 1946 that

There is no organized hunting of these sea mammals by bounty hunters; they are generally taken coincidentally with fishing operations or by Natives seeking their pelts for the manufacture of moccasins & parkas, both of which items are sold in considerable quantity to tourists.

He further noted that the number of pelts harvested was negatively related to the health of the economy; that is, when the economy was poor the annual pelt harvest tended to rise, and vice-versa. [76]

The Alaska legislature was not particularly concerned, in its bounty bill, with seal predations on the Kenai Peninsula; most of the commercial fishing took place along the peninsula's western coastline, while the only significant seal populations lived along the southern coast. Even so, peninsula residents were quick to take advantage of the new law. Several Port Graham and English Bay Natives found new sources of wintertime cash by collecting seal bounties. In Seldovia, seal hunting was also active. Graduate student Richard Bishop concluded that the activity was "kind of universal along the coast." There were "a number" of coastal seal hunters, who together comprised "a steady, small-scale industry." It is not known, however, if residents of English Bay, Port Graham, or Seldovia ever hunted seals within the present park boundaries. [77]

Non-natives living in Seward also responded to the law and began hunting seals in the various bays and fjords southwest of town. According to Richard Bishop, who spoke to several seal hunters during the early 1960s as part of a graduate research project, the activity was "a long standing practice" both in Aialik Bay and in the East Arm of Nuka Bay. [78]

Perhaps the most avid local seal hunter was Pete Kesselring. Although he earned money as a game guide and also hunted and trapped for food, seal hunting was an important part of Kesselring's income for a number of years. When he began hunting is uncertain, perhaps as early as the mid-1930s, but by the mid-1940s he was making yearly expeditions to the various bays and fjords south of town; favorite locations were Aialik and Harris bays. [79]

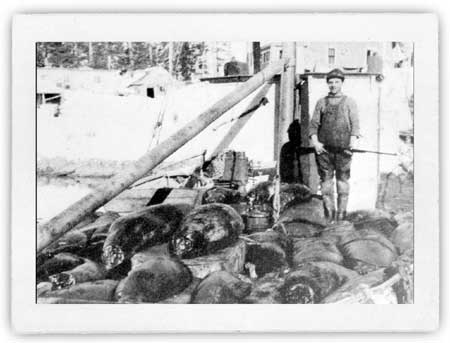

|

| Longtime Seward seal hunter Pete Kesselring at his Aialik Bay seal-hunting camp, 1955. The camp was set up in early May, just above the high tide line. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 18. |

|

| Pete Kesselring processing a newly-killed harbor seal. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 21. |

Another seal hunter was Bernard W. (Bill) Younker, who arrived in Seward in the early 1940s and began hunting seals soon afterward. Younker, who was also a big game guide, hunted seals each year; as he noted in an Alaska Sportsman article, he typically left Seward in early May and returned in mid-July, when the seals began migrating away from the fjords. A 1955 hunt with Pete Kesselring, to Aialik Bay and Holgate Glacier, resulted in a harvest of almost 800 seals; they earned money from both the bounty and from the sale of seal livers (to markets in Seward) and hides. He noted that "we're bounty hunters, and although [the bounty] isn't going to make millionaires out of us, along with a few ‘bucks' for livers and hides we manage to keep beans in the pot, and we have a lot of fun doing it." [80]

|

| Bill Younker hunted for harbor seals during the 1950s. In July 1957, he filed for the Aialik Bay homestead that was later awared to William F. Hart, Jr. Alaska Sportsman, August 1956, 21. |

Other local residents who commonly hunted seals prior to 1960 were Pete Sather, the Nuka Island fox farmer, who (as noted above) often harvested seals for fox food, and Bob Evans, the homesteader who occupied the cabin on the east side of McCarty Fjord during the 1930s and early 1940s. William F. Hart, who homesteaded the site just north of Coleman Bay (near Aialik Glacier) in 1959, hoped to use the site to hunt seals; there is, however, no evidence that he ever did so. [81] Longtime resident Seward Shea noted that Harold Cedar, Cecil Torgramson, Hank George and Ralph Grosvold–the latter a Kodiak resident–also hunted seals during this period. Shea also felt that "perhaps 10 to 20" others (beyond the four just mentioned) hunted seals, although some of that number hunted in areas southeast of town, such as Bainbridge Passage. [82]

Some locals, with the help of Pete Sather, engaged in wintertime seal hunting. As Josephine Sather explained in 1946,

In the winter, when work was scarce, some men would go seal hunting for the bounty.... To hunt seals you need a power boat to get to their grounds, and a skiff. Since few bounty hunters had either, [Pete] would take them and their camping outfits to some glacier on salt water; let them use one of our skiffs; and carry their mail and supplies to them. In return, they would give us the seals after they had been scalped. We often obtained as many as two hundred seals in a season. In the winter the seals are extremely fat, the largest of them having as much fat on their bodies as a good, fat hog. [83]

|

| In order to feed their foxes, the Sathers and other fur farmers sometimes relied on bounty hunters to provide them with seal carcasses. Alaska Sportsman, September 1946, 19. |

Alaska's legislature, as time went on, evidently felt that the bounty was an increasingly effective seal management tool. In order to increase the harvest, it increased the bounty in 1939 from $2 to $3; ten years later, it was briefly raised to $6 before being reduced again to $3 in 1951. The legislature also toyed with the area in which seals were bountied. In 1949, for example, the boundaries were extended to cover the entire territory; in 1951, it was reduced to include the former (1927) boundaries, plus Bristol Bay, Norton Sound and Kotzebue Sound; and in 1962, the boundaries were once again extended to cover all of Alaska's coastline. Throughout this period, the bounty remained in effect for seals harvested off the Kenai Peninsula. [84]

The legislature was bullish on the bounty program, both in response to citizen concerns and because its members felt that salmon constituted an important part of the harbor seals' diet. Those assumptions, however, began to slowly unravel during the 1940s and 1950s. Of the six species for which the legislature offered bounties, two species had their bounties eliminated during this period: the Dolly Varden in 1941 and the bald eagle in 1953. [85]

Meanwhile, a growing body of science was questioning the scientific assumptions behind the harbor seal bounty. Acting on a March 1944 complaint "about the seal herd at Cordova," the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service decided to study the feeding habits of both seals and sea lions in Alaskan waters. Frank W. Hynes, who headed the agency's Alaska office, had heard that "the Seward area and to the westward" had major sea lion depredation areas, so he contacted Roy L. Cole, the longtime skipper of the patrol boat Teal about the matter. Cole, in response, urged that the proposed study take place at the Seal Rocks, near Seward, inasmuch as the sea lions there were relatively easy to study. In the spring of 1945, therefore, Hynes dispatched Ralph W. Imler to the field. Imler, as suggested, visited the Seal Rocks and estimated that 400 to 500 sea lions inhabited them, but owing to rough seas, he was unable to work there without a large boat. Imler spent much of the summer on the study, which was conducted at the Copper River mouth, at the Chiswell Islands, and elsewhere. By the spring of 1946 the study was complete; its conclusions debunked the prevailing attitudes by showing that salmon were a minor part of the harbor seals' diet. Most of their diet consisted of "oolachon" [eulachon] and other species. According to one agency official, "it is not believed that the hair seal is a factor to be concerned about in the conservation of the salmon runs. No federal control measures are believed necessary." [86]

An agency official followed up Imler's study by observing harbor seal predations at the Stikine River mouth, near Wrangell. He concluded that the present bounty should be continued and that seals were "a costly nuisance" to several of the area's gill net fishermen. Losses here, as well as at the Taku and Copper River mouths, were estimated at "from 2 to 10 per cent of the fish caught [by commercial fishers] or even more." [87]

The Alaska Territorial Department of Fisheries, which was organized in the late 1940s, recognized that the bounty–even when set at $6 per seal, as it was in 1949 and 1950–was an ineffective way to control seal populations and thus reduce damage to the territory's fish runs. It therefore responded to area-specific complaints by instituting a small-scale program of seal control. In 1951, a summertime employee was stationed at the mouth of both the Stikine and Copper rivers, where rifles were used to dispatch harbor seals. The program was judged successful. The following year employees returned to those sites, and a third employee was stationed at the mouth of the Taku River. The program continued until 1958; at the end of that season, officials proudly noted that since its inception 36,163 harbor seals had been killed: 30,250 at the Copper River, 4,999 at the Stikine River, and 914 at the Taku River. [88]

Territorial officials never had any illusions that hired hunters would eliminate the "seal problem" in those areas. They were glad to note, however, that they had made a "large impact" on certain of those populations. By 1957, however, they readily admitted that the program might have been misdirected and that "seals eat more than just salmon." They agreed that the problem was complicated and that it needed further study. [89]

During the 1958 season, territorial biologists did indeed study the problem in greater depth. They found that while a number of seal that were harvested from the Copper, Taku, and Stikine River mouths had salmon in their stomachs, none of those caught elsewhere in the territory showed evidence of salmon ingestion. This conclusion cast a strong doubt on the value of a bounty as a territory-wide management tool. The agency further concluded that "the bounty system is not providing adequate protection from depredations by ... seals, and that planned programs [such as those at the three river mouths] can do the job with smaller expenditures." "In other areas," a report noted, "seals may actually be a benefit to the salmon fishery." The report made the somewhat startling conclusion that "hair seals also have value in themselves and should not be destroyed where it is unnecessary." [90] The implication was clear; the bounty system should be eliminated, and area-specific control methods were the only ones that worked. The year 1958, however, brought congressional passage of a statehood bill. Once statehood was attained, site-specific predator control at the three river mouths was abandoned and the $3 harbor seal bounty remained in place.

Harbor Seal Harvesting, 1960 to

Present

During the early 1960s the harvesting of harbor seals, both along the Kenai Peninsula and elsewhere in Alaska, continued at a low level (less than 20,000 per year statewide), and the prices garnered for seal pelts likewise remained low ($10 or less per pelt). [91] Then, in the fall of 1962, the demand for seal pelts began to increase because of changes taking place thousands of miles to the east. During the 1950s and early 1960s, the commercial seal market–particularly the huge Scandinavian market–had depended on seals that were harvested in the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. (Europeans, and to a lesser extent North Americans, used seal pelts for a variety of clothing and accessory items, including shoes, purses, coats, hats, and other items of over-clothing.) By 1962, however, overharvesting in the traditional hunting areas had reduced the available supply. European fur processors, which were located primarily in Norway and West Germany, began to look elsewhere for seal pelts. [92]

Many fur buyers eyed the huge Alaskan fur resource. Between the fall of 1962 and March 1964, the value of both spotted [harbor] and ringed seal pelts more than doubled; in response, there was a "tremendous increase" in seal–mainly harbor seal–harvests beginning in 1963. (It had a "considerably less effect" on the take of bearded and ringed seals, which are a dietary mainstay of northwest coastal residents.) The value of seal pelts continued to rise until 1965. By the mid-1960s, black harbor seals (with large, black hides and definite spots) were worth $60, while young plain grays brought $15 to $20. The annual pelt harvest, which before 1962 had exceeded 20,000 only thrice–in 1907, 1949 and 1950–shot up to 30,000 in 1963, to 40,000 in 1964, and to 60,000 in 1965. After reaching that high point, prices decreased again, though not to former low levels, and the harvest declined as well. [93]

The "bubble" in fur prices brought increased harvesting activity to the southern Kenai Peninsula as well as to other parts of the state. In Aialik Bay, for example, 649 seals were harvested in 1964, and in Harris Bay, 946 were harvested in 1964 and 596 in 1965. In Nuka Bay, more than a thousand seals were taken per year during the mid-1960s; a total of 3,420 were taken between 1964 and 1966, inclusive. These numbers, though impressive, constituted only a small percentage of the estimated 145,000 harbor seals harvested in Alaska during the 1964-66 period. Most of the state's harvest took place in Prince William Sound, the Alaska Peninsula, the Aleutian Islands, and the Kodiak Island archipelago; the state's largest specific harvesting sites were at Tugidak Island (south of Kodiak Island), Port Moller (on the north side of the Alaska Peninsula), and Port Heiden (near Port Moller). [94]

Several of the Seward-area residents who had hunted seals in the area prior to 1960 continued to do so, but others (including Pete Kesselring and Pete Sather) did not. The increased prices, moreover, attracted new hunters. Two were the Burch brothers, Al and Oral, Seward fisherman who supplemented their income by hunting seals near Aialik and Holgate glaciers from October until February. Two brothers from Homer were also "real serious hunters." Pete Elvsaas of Seldovia hunted "all along the outer coast," and hunters also came to the area from Prince William Sound. Other Seward seal hunters included Jesse Hatch and his brother Ralph, Roy and Lloyd Cabana, Martin Goreson, Ben Suddath, Irving Campbell, Fred Moore, Bill Johnston, Frank Woods, and Ed ("Beetle") Bailey. [95]

An estimated 300 Alaskans during this period derived some income from seal hunting. Bounty records for 1965 tabulated 168 hunters in south central Alaska, and according to researcher Richard Bishop, perhaps 20 to 25 people each year hunted southern Kenai Peninsula seals during the mid-1960s, when prices were at their peak. Some Seward-area hunters apparently took seals just for the bounty; most, however, sold the hides as well. [96] They sold them either to itinerant buyers who traveled through Alaska or to fur buyers in Seattle. A third outlet was Victor ("Vaughn") Reventlow, the manager and director of the Alaska Tanning and Dressing Division of the Pacific Seal Corporation. By 1966, the firm was said to handle "the lion's share of hair seal coming out of Alaska." Reventlow, a West German living in Anchorage, often drove to Seward and spent a day grading the pelts before buying them. [97]

With the rise in pelt prices, the bounty became less important as an incentive to hunt seals than it had in former years. Alaska legislators, who had not acted when confronted with the program's inefficiency and misdirected expense, moved to cut back on the bounty program when shown that the $3 bounty was far less than the value of the seal pelts. (The legislators made no attempt to eliminate the bounty statewide, because they recognized that in western and northwestern Alaska, the seals were a major food source and that the bounty was "more of a welfare measure than an attempt at controlling seal populations"). [98] Bills intended to eliminate the bounty had first been introduced in 1964; HB 381 that year had been sponsored by the House Finance Committee, while SB 244 was sponsored by Sen. Harold Z. Hansen, a fisherman who chaired the Resources Committee. On March 10, HB 381 passed the House, but the following day Robert Blodgett, a Teller Democrat, changed his vote and the House voted down the bill on a reconsideration vote. The Senate bill did slightly better; it passed the Senate on March 17, then was referred to the House Finance Committee. That bill quietly died because Harold Strandberg, an Anchorage Republican and the committee's chair, failed to act on it. [99]

Three years later, after Walter Hickel became governor, the Rules Committee of the Alaska Senate, at Hickel's request, submitted SB 131, a bill that, like the 1964 effort, would eliminate the hair seal bounty. The 1967 bill was introduced on February 21. On March 24, it failed to pass the Senate, but a day later, Sen. Brad Phillips changed his vote and the bill passed. Nine days later, it passed the house with 13 dissenting votes, and Governor Hickel signed the bill on April 6. The bill, which immediately became law, eliminated the bounty for all seals harvested in the waters of Kenai Peninsula and many other parts of Alaska. [100]

The repealing of the bounty slightly reduced the financial incentive for Kenai Peninsula seal hunters. A more important factor in reducing seal harvests was a drop in the price of seal skins. Because of the publicity surrounding the clubbing of seals by Canadian harvesters, Europeans organized a boycott on products made of seal skins. By 1966, therefore, seal skins were worth anywhere from $4 to $30, their value averaging about $13. In later years, the value of seal skins continued to slide, and by 1972 there were "depressed prices in the hair seal market." [101]

If the dual blow of the bounty removal and the slide in prices were not bad enough, seal hunters after 1965 recognized, for perhaps the first time ever, clear signs of seal overharvesting. Hunters found fewer seals and in less accessible locations, and because most had simple equipment, it took more work to locate them. Not surprisingly, therefore, the number of seals harvested from southcentral and southeastern Alaska waters dropped from more than 50,000 in 1965, to 27,000 in 1966, and to between 15,000 and 20,000 in 1968. By 1969, harvests had leveled off; for the next four years, hunters harvested between 6,000 and 12,000 skins annually. Given the falling harvest levels, the number of hunters fell as well; in just a single year, the number of southcentral area hunters dropped from 168 (in 1965) to 90 (in 1966). Within the present park boundaries, hunters continued to utilize the seal resource. Neither the number of hunters nor the size of the harvest during this period is known, although the level of activity was doubtless less than it had been during the mid-1960s. [102]

A far more dramatic action affecting the seal harvest, both on the Kenai Peninsula and elsewhere in Alaska, was the passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act. This act, which was signed by President Nixon on October 21, 1972 and went into effect two months later, nullified all state laws relating to the taking of all marine mammals (including seals) and placed the authority for regulating the take of seals under the U.S. Secretary of Commerce. The law prevented non-Natives from taking seals. Section 101(b) of the act allowed Alaska Natives to do so without limit, so long as such taking was either for subsistence or handicrafts purpose and was not done in a wasteful manner. [103]

So far as is known, most Alaska seal hunting ceased after the passage of this act. In 1971, the statewide harvest had exceeded 25,000 seals, but in 1973, the harvest "probably did not exceed 1,000 animals." Within the present park boundaries, a 1975 Interior Department planning document noted that "Hair seal ... are hunted in the Chiswell Islands" and that "Some seal hunting may be done for the sale of furs." This statement, if accurate (it may have been based on data collected prior to the passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act), was based on Native activity from residents of either Seward, Port Graham, or English Bay. [104] As to more recent activity, harvests appear to have been minimal. When Seward's 410 Native residents were interviewed in 1991, 20.5% of Native households reported using harbor seals, although only 2.6% of the Native households harvested them. A year later, the percentages were far lower; only 0.8% of Seward Native households used harbor seals, and no households (0.0%) harvested them. [105]

Sea Lion Harvesting

Rookeries of Steller's sea lions (Eumetopias jubata) inhabit several areas in and near the present park. Their primary habitat is the most exposed islands, and the area's two largest rookeries are the Chiswell Islands, at the southwestern entrance to Resurrection Bay, and the Barren Islands, near the southwestern tip of the Kenai Peninsula.

Sea lions, along with fur seals, elephant seals, and sea otters, were subjected to an enormous amount of commercial hunting pressure during the 19th century, and by 1905 a government fisheries expert noted that sea lions were "almost extinct." The Alaska Game Law of 1908, however, prohibited their "wanton destruction" and decreed that no one could legally kill more than one sea lion per year. [106] The new law brought hardship to certain Alaska Natives (such as those at Akutan), who were deprived of "their only trade and occupation." The law was also looked upon with disfavor in Seward, which was beginning to acquire a fishing industry. Residents there fought the law because it protected sea lions which, as noted in a previous section, were popularly believed to be both numerous and possessed of gargantuan, salmon-based appetites. By 1916, Seward's Chamber of Commerce had a Sea Lion Committee that sent a letter to both Alaska Delegate James Wickersham and Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston. In that letter, it "was set forth that the seals [sic] at the entrance of Resurrection Bay were a menace to the fishing industry and asking that the game laws be amended to the extent that these animals could be destroyed or dispersed." [107]

|

| Steller sea lions were occasionally harvested along the Kenai coast because of their purported salmon-based diet. M. Woodbridge Williams/NPS photo, in Alaska Regional Profiles, Southcentral Region, July, 1974, 154. |

Despite the Federal government's prohibitions, local residents harvested sea lions from time to time. Shortly after Pete Sather began living on Nuka Island, he started feeding sea lions (as well as seals) to his foxes. In regards to the sea lions' feeding habits, the opinions of his wife, Josephine, were fairly typical of Alaska fishers;

On his frequent trips to Seward in the spring, Pete often brings home a sea lion.... And what a lot of fish they do eat! We have found as much as seven salmon in the stomach of one sea lion.... In spite of their large numbers and their proximity to us, sea lions are hard to get. They sink if shot in the water [and] the jagged cliffs ... make landing [them] in a skiff exceedingly hazardous.... Sea-lion killing is against the law, except when they interfere with commercial fishing. We can hardly understand why.... Halibut fishermen often have to leave good fishing grounds because they cannot get a whole fish to their boats. [108]

During World War II, the area's sea lions faced a new danger: bored soldiers. Military men, as noted in Chapter 8, were stationed on Outer Island, Rugged Island, at Caines Head, and elsewhere in the immediate area. As Josephine Sather explained it,

During the war, the service men stationed in Alaska found that sea lions made excellent practice targets. All they had to do was bring the boat up close to a rookery, then make believe they were fighting Japs. Since the fellows had plenty of ammunition at their disposal, hundreds of sea lions became feed for the fishes. Hundreds of others drifted up onto the beaches, where they made feed for birds, coyotes, and bears.

In retrospect, Alaska residents had the same attitude toward sea lions as it had toward harbor seals–that they were a costly nuisance because they were believed to eat salmon. Based on those attitudes, Congress passed the Act of June 16, 1934 that relaxed most former prohibitions on sea lion harvests, and in 1949 the Interior Secretary allowed them to be killed anywhere in Alaska except on Bogoslof Island, near Unalaska. [109] If the 1908 prohibition on excessive sea lion hunting had not been imposed, Alaska legislators may well have placed a bounty on sea lions as well as harbor seals. Given that prohibition, no such bounty was ever enacted.

When Alaska became a state, it became free to regulate the take of sea lions and other marine mammals, and the federally-mandated stricture against hunting them no longer applied. They were free to impose a bounty, too; the era of new bounties, however, was long past. State officials allowed sea lion hunting throughout the state; the taking of sea lions for commercial purposes, however, was permitted only under the terms of a permit issued by the Commissioner of Fish and Game. That permit specified which areas would be open to sea lion harvesting. The Barren Islands, southwest of the Kenai Peninsula coastline, were included as a commercial harvesting area. [110]

Under that system, a recorded total of 45,808 sea lion pups were harvested from Alaskan rookeries from 1959 through 1972. The same trend which created an increased harbor seal take carried over to sea lions as well; sea lion pups were harvested for their pelts, and there was an experimental harvest of adults for meat. (Commercial interests hoped to sell meat and liver as pet food or to fur farms, and Japanese interests hoped to find protein for human consumption. High costs, however, precluded further development of the resource.) Hunting locations were highly localized; 31,070 of those sea lions–more than two-thirds of the total–came from either Marmot Island, near Afognak Island, or from Sugarloaf Island, in the Barren Islands. Much of the remainder came from either Akutan or Ugamak islands, both of which are located just east of Unalaska in the Aleutian Islands. [111]

Along the Kenai Peninsula coast, a commercial take has never been allowed within the park boundaries; outside the park, as noted above, commercial permits have been issued for the Barren Islands, but not for the Chiswell Islands. Quite a few local residents attempted to harvest sea lions in park waters, particularly during the mid-1960s when pelt prices were high; they all quickly learned, however, that the proposition was uneconomical and they abandoned the practice. [112]

The harvest of sea lions, like that of hair seals, was drastically reduced when the Marine Mammals Protection Act was passed in late 1972. Since then, few if any sea lions have been harvested in park waters. The only group legally allowed to harvest them has been Alaska Natives. Local Native groups, however, avoid them; a series of three annually-administered subsistence harvest surveys, conducted during the early 1990s, revealed that Seward's Native population neither harvested nor consumed sea lion. [113]

|

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from Wilderness, A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, 1920. The Rockwell Kent Legacies. |

kefj/hrs/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002