|

Historical Introduction Of earth, stones, and timber, but mostly earth, hulking pylonlike in silhouette, heavy, inert, functional, seemingly immutable but ever crumbling—praised, damned, and belatedly praised again—the Spanish mission churches of New Mexico issued from a union of European ideals and an outlandish environment. The architects were European Franciscans who came not straight from the lands of their birth but by way of the massive, half-century-long spiritual conquest of Mexico. Permanent Christian occupation of the new Mexico, beginning in 1598 at the very end of Spain's golden age of empire and religion, was in fact an extension, in both time and territory, of that earlier spectacular ministry. In the heartland of Mexico the friars erected of skillfully dressed stone monumental "fortress-churches" (a term derived more from appearance than use) on solid Old World foundations, but simplified, as in thirteenth-century southwestern France, to an austere, towering single nave. Carried to New Mexico, to a semiarid frontier environment where inconstant adobe, field stone, and wood replaced reliable masonry, such ideals were further compromised. Suppressed were the grand rows of buttresses, the rib vaulting, and most lateral windows and doors. Local materials, relatively few and unskilled workmen, poverty, and isolation all contributed to a unique and, as it turned out, an all but invariable New Mexican style.

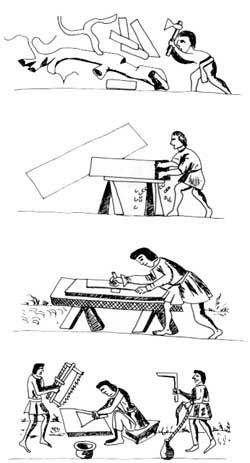

The few heroic attempts to capture in sun dried mud and loose stone the dynamic essence of hard masonry—as at Pecos in the 1620s and at Abó in the 1640s—were less transitional than experimental. After that, the friars conformed. In the words of George Kubler, "The seventeenth-century adaptation of adobe to baroque form, and vice versa, constituted a stylistic end term. The later history of architecture in colonial New Mexico is comparable to that of the tissue which, divorced from its host, goes on proliferating, always identical with itself, until the favorable conditions in which it thrives are suppressed." Those "favorable conditions" persisted for two hundred and fifty years, until the mid-nineteenth century, when the first resident bishop, new avenues of supply, new immigrants, and new technology all converged on New Mexico at once, altering notably or replacing entirely the architecture's long-familiar form. But until then, the "missions" of New Mexico all fit essentially the same mold. There was variation in placement, orientation, size, and quality of workmanship, but in little else. The Spaniards' introduction of the adobe, a form-shaped, sun-dried block of earth, was less revolutionary than convenient. Local soil, having suitable proportions of clay and sand, could be mixed with water to a doughy consistency, shaped in a bottomless wooden box, and dried by the sun hard as a rock. Too much clay in the batter made the blocks shrink and crack in drying. Too much sand produced crumbly adobes. Although dimensions varied considerably during colonial times (10 by 14 by 4 inches is more or less standard today), the weight of the block rarely exceeded 40 pounds, about as much as any adobe layer could handle. Building with adobes was easier and quicker than the Pueblo Indian "puddled earth" method, in which the workers heaped a quantity of stiff mud on a wall and then went away to let it dry. The adobe offered a more practical way to get the earth in place. Yet it did not greatly influence the form of a structure.

What did influence form was the invaders' insistence on erecting churches of churchly proportions whatever the materials. The Spanish mission church enlarged upon the tradition of Pueblo Indian builders in at least two fundamental ways. It rose straight up, instead of in low stories stacked and set back one upon the other. And it enclosed, to the greater glory of the imported god, an unfamiliar vastness of vacant space.

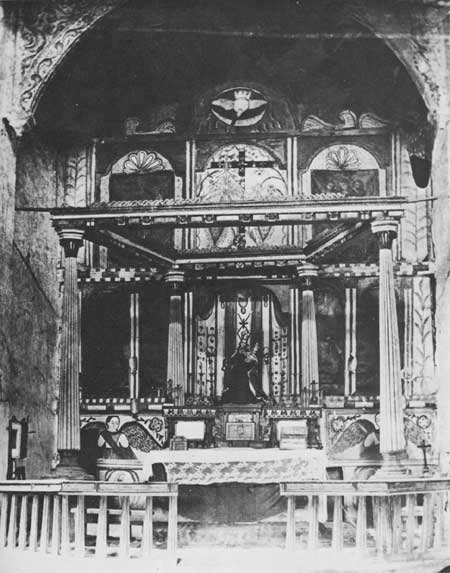

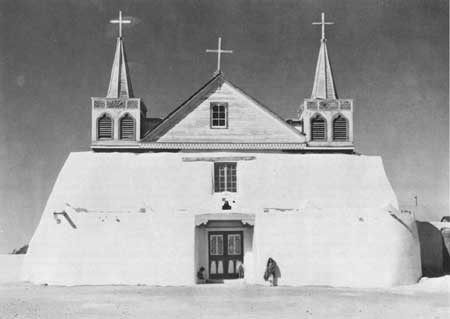

The massive blank walls of the church dominated the close-built native pueblo and later the Hispano plaza. In profile it looked like a mesa set down in the community, flat-topped but with the sanctuary end raised uniformly to somewhat higher level and the other end surmounted by the outcropping of tower or bell gable. Here the precise symmetry of most temples was missing. Nearly every detail, from the monolithic massing of walls to the clumps of grass growing on the dirt roof, reinforced the illusion that this was not so much a work of man as of the elements themselves. One entered the typical New Mexican mission church through an atrio, the large walled yard in front, past the rude cross erected in the center. This, along with the packed earth floor of the church itself, served as the burial ground. The facade of the church might be no more than a featureless end wall with rectangular wooden door, small square choir loft window, and some sort of geometric parapet pierced by holes for a bell or two. Or it might be flanked by towers, either flush or projecting out from the wall and forming a recess for the doorway. In some cases above the door a balcony with wooden balustrade, which one reached by climbing through the choir loft window, bridged the recess. Sometimes, too, the ends of the vigas, or beams, spanning nave and sanctuary, poked through the lateral walls of the church like the guns of a ship of the line riding high in a calm sea. Inside the heavy walls it was dim and cool. The effect from the entrance under the choir loft was one of great length. As one's eyes adjusted to the semidarkness, they focused almost in voluntarily on the sanctuary, where an ethereal bath of light fell upon the altar. Even the plain undulating white walls tended to converge in that direction. Overhead a progression of thirty or forty large exposed beams, usually round and set two or three feet apart, lent a dark, richly textured contrast. Each beam rested on a pair of hefty wooden corbels, which together in perspective created the illusion of a somewhat vaulted ceiling. The corbels, and occasionally the beams as well, displayed geometric designs gouged with chisel and painted.

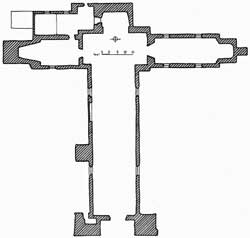

The interior dimensions might measure twenty-five by eighty feet or more. Width was determined by the length of roof vigas available to span the void, length by the size of the congregation. As a rule, wall height never exceeded width. The notion that seventeenth-century churches built in Indian pueblos were typically rectangular, while eighteenth-century churches built in Hispanic settlements were typically cruciform, suffers from so many exceptions that it ought to be discarded.

Because the furnishings were so spare, some visitors were reminded of an empty warehouse. There were no pews, only a confessional and perhaps a bench or two along one wall. The carved wooden pulpit, elevated on a pedestal, clung to the Epistle side. Side altars, if present, were narrow and built against the nave walls, or recessed in the arms of the transept if there was one. The floor level of the sanctuary was raised several steps. The lower portion of the whitewashed nave walls might carry decorations in water-soluble paints, sometimes only a solid color dado or a band of undisguised Pueblo Indian motifs. Such adornment could be intensified at the sanctuary until it looked "like a tapestry." Above the main altar, if the painted wall itself did not serve, stood the carved and painted wooden reredos, or retablo, forming a matrix for the patron and companion saints who stared out from timeworn statues or from animal-hide paintings.

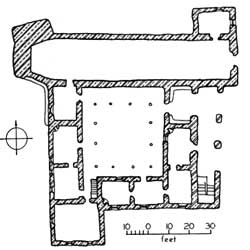

Two or three high-set and inaccessible little windows let in a feeble, diffused light between upright wooden spindles or through "panes" of native selenite. Curiously, in most of these churches all of the windows were on one side. The wall opposite stood unbroken. Toward that side the roof was slightly inclined so that water would be carried off through wooden spouts, or canales, poking through the parapet. The main source of light was hidden from the nave. Architecturally speaking, this was "the most characteristic feature of the structure." Confined as they were to post-and-lintel construction with few arches and no domes, the early friars had a problem illuminating the sanctuary of their earthen temples. Their solution—the transverse clerestory window—was ingenious. There may have been precedents in sixteenth-century Mexico, but nowhere was this feature developed so fully or used so effectively as in the missions of New Mexico. It spanned the structure, a wide low overhead window framed by the two beams, one above the other, at the difference in roof level between the lower nave roof and the taller roof of transept or sanctuary. Inside, the effect was more than satisfactory. It was theatrical. Peering down the long tunnellike nave from the doorway, the viewer focused immediately on the stream of light descending like the Dove precisely on altar and reredos. As for auxiliary rooms, they huddled against the church where needed, the baptistery off the nave to one side of the entrance and the sacristy beside the other end with access from transept or sanctuary. A convento, from conventus, the Latin word preferred by the Franciscans to describe their dwellings, abutted the church on the protected side, generally on the south if the parent structure ran east-west, or on the east if the church was oriented north-south. Sometimes two-storied but more often only one, the convento buildings formed a quadrangle enclosing cloister and patio within. Here the friars—or a friar, as was usually the case in New Mexico—had their cells, kitchen, workrooms, storerooms, and "porter's lodge." Walled corrals, with stalls and haylofts, and a garden lay beyond.

Because of the crumbly and temperamental nature of adobe, the well-kept church and convento were constantly under repair. The annual mud plastering of the walls by the women became almost a part of the liturgy. But more than the walls, it was the incredibly heavy roof that threatened collapse. On top of the bearing vigas, at right angles or alternating diagonally in a herringbone pattern, lay cedar poles (latillas, variously called savinos, cedros, or rajas, depending on preference and whether they were split or round) or rough-hewn boards (tablas). A layer of matted plant fiber was next, and then dirt, tons and tons of it, a foot or more deep, with a layer of hard-drying mud slicked over the lot. When wet it was even heavier, and when the wood began to rot the whole thing had to be replaced. This periodic reroofing was in fact an undertaking of such consequence—entailing, as it frequently did, the rebuilding of several courses of the walls as well—that those responsible tended to take credit for "a new church," a habit that badly muddles the historian who would presume to peel off neatly one by one the succession of churches in any given pueblo. Then too, without archaeological spade work, it is impossible to say whether a wholly new adobe church occupied a new site or whether it had been raised up right on top of the crumbled mass of a previous structure. [1] THE FRIARS

The Franciscan friars who came with Coronado in 1540, the luckless and the visionary, were gambling, taking time out from the spiritual conquest of Mexico to see what manner of cities lay far to the north. Disappointed, they nonetheless set up crosses in the Indian pueblos, as was their custom, and bade the native peoples to venerate them. Then, with the exception of Fray Juan de Padilla who soon died on the plains and Fray Luis de Úbeda who died in the pueblos, they withdrew. They built no churches. [2] Churches, whether of cut-stone masonry or of adobe, imply permanence. When next the invaders came in force, it was plain they meant to stay. Proprietor Juan de Oñate, his colonists, and his Franciscans moved in deliberately. And within weeks, at a Tewa pueblo, seized and christened San Juan, they had a church, New Mexico's first, "large enough to accommodate all the people of the camp." On the day of its dedication, feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, September 8, 1598, Spaniards and Indians, masters and servants crowded inside for solemn high Mass. All ten friars assisted. After the Last Gospel, don Juan Pérez de Donís, Oñate's secretary, a gray-bearded gentleman with an old scar across his forehead, stood up to read a long proclamation. By the special authority vested in him, Governor Oñate did

A listing of provinces and pueblos followed Oñate's concession. From the Piros on the Rio Grande in the south to Taos in the north, and from the Hopis in the west to Pecos and the plains in the east, the entire kingdom of New Mexico had been placed in the spiritual care of the Franciscans, at least on paper. [3] The Oñate years, 1598 to 1610, which began so hopefully for the friars, proved instead a time of trials. First a bloody battle with Ácoma forced them to fall back on the area around San Juan. At San Ildefonso and at one of the Jémez pueblos they had built churches by 1601, but that same year seven of the Franciscans and most of the colonists deserted. Because Oñate had found no resources to make New Mexico pay, he had been squeezing the Pueblo Indians. "We cannot preach the Gospel now," the friars lamented, "for it is despised by these people on account of our great offenses and the harm we have done them." Let the government take over the colony, they urged. Abandon it, said others. Oñate resigned in 1607. For a time New Mexico's fate hung in the balance. But when the Franciscans, playing on the Christian conscience of the Spanish crown, claimed the mightily inflated figure of seven thousand Pueblo baptisms, they won the day. Beginning in early 1610 with the arrival of a supply caravan, more friars, and the newly appointed Governor Pedro de Peralta, New Mexico ceased to be a proprietary investment of the Oñate family and became instead a wholly government-subsidized, royal missionary colony. Henceforth, until the Pueblo Indians rose in 1680 and drove the Spaniards out, the missions were New Mexico's reason for being.

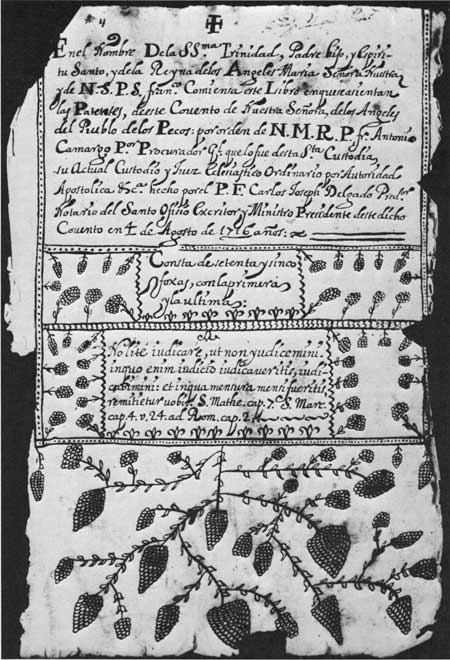

That gave the Franciscans the upper hand. Financed by the royal treasury, unchallenged by bishop or rival religious order, wielding for themselves the powers of prelate, ecclesiastical judge, and agent of the Inquisition, the colony's only priests, they enjoyed a formidable spiritual monopoly. In 1631 the crown contracted to support sixty-six friars, a quota rarely full in the field. Four more were added later for the El Paso district. In remote New Mexico the Franciscans were the Church. [4] Square in their path, however, stood the equally jealous royal governor and his appointees, whose use and abuse of political and military command gave them weapons of their own. At issue was the colony's primary resource, the Pueblo peoples, a limited and declining commodity. The missionaries wanted the natives' allegiance, their labor, and their produce in the name of salvation. The civilians would take it all in the name of king and reasonable profit. In the ensuing competition, which at times verged on civil war, the contending parties' honor and dignity were frequently offended and almost every aspect of life in the colony was affected, including the building of churches. In terms of what was available, the construction, maintenance, and furnishing of New Mexico's mission churches demanded incalculable Pueblo Indian labor, most of it, charged the opposition, unrecompensed and unnecessary. One governor, the brash don Juan de Eulate, branded by the Franciscans "a great enemy of the building of churches," allegedly threatened in the 1620s to hang Indian construction workers and to punish severely any Spaniard who lent his oxen. Bernardo López de Mendizábal, they said, went around protesting in 1660 that all the missionaries needed were a few straw huts and some ordinary cloth vestments. Shifting the blame, López accused the friars of professing the ideal of grand and expensively adorned churches only to keep the Indians enslaved, while in reality, he said, "the temples of those provinces are not objects for admiration, nor are they sumptuous, for they are very small, with walls of mud and adobes, built without skill and at no expense." Still, the churches went up. [5]

As in Mexico, the friars were the architects. They learned by doing. Supplied from time to time with hand tools, some items of hardware, and various religious furnishings, they improvised the rest on site. They used the few Hispano craftsmen available for hire and a lot of native labor. Accepting the specialization they found in Pueblo society, they set the women and children to laying up walls while the men hauled materials with borrowed oxen and learned new ways to work wood. The Franciscans cannot have relied on coercion: they were too few. In many cases, it seems, they followed a pattern, first arranging with the Indians for a block of existing rooms where they lived while supervising construction of a small preliminary church. Then later, when they had earned acceptance, grudging or otherwise, they set about building a proper, even monumental, church and convento, which might take years. Whether cherished or despised, or merely tolerated, these adobe temples stood as the most visible signs of the missionaries' success. One report, evidently compiled in 1641, listed specifically twenty-eight churches, labeling ten "very good" and the rest from "fair" to "most beautiful." The Taos had rebelled and destroyed theirs, and the Zuñis had brought down several more. But despite such setbacks, the building went on. By 1660, the peak of the missionary era, New Mexico's friars could boast forty-five to fifty churches. [6] But they had overbuilt. In the 1670s missions began to fall away. Drought and disease, hunger, the Apache scourge, and Spanish oppression put the peoples of the Saline pueblos to flight. Among Hopis, Jémez, Piros, Tanos, and Zuñis, the friars curtailed their ministry. Churches stood vacant. When at last the Pueblos united in their great purge of 1680, each community dealt with its church in its own way. Destruction was by no means universal. Some churches, those in the north particularly, they ravaged thoroughly. The grandest of all, the soaring monument at Pecos, was fired, gutted, and seemingly thrown down adobe-by-adobe until all that remained was an enormous mound of earth. Most churches suffered only partial demolition. Walls were left standing and used as corrals. At Ácoma, where the people had hauled to the summit every cubic foot of earth and stone on their backs, they did little damage. Church and convento survived almost intact. [7] Whether they brought them down or let them stand, the Pueblo patriots of 1680 were expressing in the extreme a feeling their descendants still share, a feeling of complete possession. The mission churches belonged to them. They had built them, they maintained and repaired them, and, when free of constraint, they chose whether they stood or they fell. No matter that the architect-construction boss-priest acted as if he were the owner. He was an outsider. If he wanted to keep the people's good will he came to the principales first with his plans to expand the nave, add a steeple, or restore the flat roof. To this day the Archdiocese of Santa Fe does not hold legal title to most Pueblo churches. [8]

For all his pious rhetoric, don Diego de Vargas, the reconqueror of New Mexico, did not restore the seventeenth-century missionary colony. He avenged the affront of 1680 and planted an outpost of empire. It was a new colonization. From the 1690s on, military considerations outweighed missionary. The crown supported only half as many Franciscans in the eighteenth century. As a rule they received a fixed annual allowance of 330 pesos each, with less for lay brothers and more for presidial chaplains and missionaries exiled to the hardship post at Zuñi. The quota in 1763, high because it included a dozen friars for the missions of El Paso and La Junta downriver, was thirty-four priests and a lay brother. In pesos, that came to 11,450. By comparison, the payroll for the Santa Fe garrison that same year totaled 32,065. [9] Meanwhile, the Pueblo mission field shrank. Remnant Jémez, Tanos, and Zuñis shifted about and came down to one pueblo each. No one repeopled the deserted Saline communities of Abó, Quarai, "Gran Quivira," and the others. Elsewhere, Hispanos moved in. One new congregation of Pueblo refugees did take hold at Laguna in the late 1690s, but others fled to the Hopis, who after 1700 never again tolerated another mission. Not only did the number of missions drop in the eighteenth century, but so, too, did the overall Pueblo population. In fact as it fell from perhaps thirty thousand to nine or ten thousand, the Hispanic population climbed to parity and then surpassed it. By the end of the century there were twice as many Hispanos as Pueblos. For the friars that meant more and more time ministering to the Hispanic community and less and less as missionaries to the Pueblos. At the same time, their spiritual monopoly broke down. Three bishops of Durango, eager to validate their authority over the Church in New Mexico, actually visited the province, in 1730, 1737, and 1760. Still, because of the remoteness, the poverty, and the danger, few diocesan priests, with the notable exception of New Mexico's native Santiago Roybal, cared to stay. A New Mexico parish was no prize. So long as there were friars to serve, they could have it. Church building, meantime, increased in quantity and decreased in quality. In contrast to the seventeenth century when the Franciscans initiated all of it, civilians now frequently took the lead, as governors and prominent citizens left monuments to their personal piety. There were few innovations. The adobe shells still standing after the Pueblo Revolt, repaired and reused in some cases, served as models. In the Indian pueblos new churches tended to be smaller and lower, a reflection of population loss, while in Santa Fe, Santa Cruz, and Albuquerque, the Spanish villas, they were larger. Almost everywhere the workmanship was inferior, cruder than it had been during the previous century. Foundations were looser, walls and joints less precise, and carpentry less skillful. As a result, the buildings did not last as long.

Some attempts were made to keep the churches clean. Across the sanctuary ceiling decorated animal hides were stretched and tacked to the vigas to serve as a "firmament" for the main altar and to catch the dirt falling from the roof. In 1731 Father Juan Miguel Menchero admonished the friars in the name of decency and cleanliness to expel the nesting swallows from their churches. More than a century later a U.S. Army lieutenant was reminded of the 84th Psalm: "Yea, the sparrow hath found an house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, even thine altars, O Lord of hosts, my King, and my God." Menchero also called on his missionaries to emulate the zeal of the "old Fathers" in maintaining the fabric of their churches and conventos, especially in "repairing drains and other things that can cause their destruction." [10] Nevertheless, eighteenth-century churches and conventos had a habit of falling down. The average structure, it would seem, underwent in just those hundred years two or three major reconstructions. Santa Cruz threatened collapse in 1732. Sixty years later, much-repaired San Felipe Neri at Albuquerque did collapse. Both were replaced. Tesuque at mid-century had to be rebuilt from the foundations up, as did San Juan, Santa Clara, Santa Ana, and Zia, to name several that can be documented. Galisteo was falling in 1776, and so was Sandía, a building not yet thirty years old. Age, meanwhile, was taking its toll of the Franciscans themselves. As their ministry evolved from mainly Indian missions to mainly routine parish administration, as the numerical strength and the quality of the clergy withered, much of the old zeal disappeared. Laboring at Santa Fe or Albuquerque as parish priests, friars of necessity took fees for their services. Elsewhere they winked at Pueblo ceremonials and kivas. They preferred the relative comfort and safety of the Rio Grande settlements to Pecos or Zuñi. Granted, there were many exceptions, the likes of Carlos José Delgado and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante. Still, these men recognized how much times had changed and it pained them.

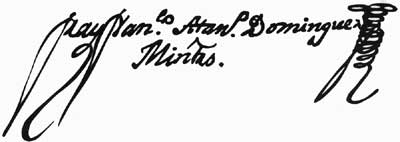

Nowhere was the gulf between the pious expectations of the seventeenth century and the scabby reality of the eighteenth more candidly plumbed than in the reports of keen, methodical, witty Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, special inspector to the New Mexico missions in 1776. He told it like it was. Domínguez was an outsider. He was also a perfectionist. Although he recognized the utility of New Mexico's adobe churches given the country's poverty and isolation, he could scarcely bring himself to say a kind word about them. In fact he rather enjoyed comparing them to dungeons, granaries, or wine cellars. At Santa Fe, with its three churches, he fondly recalled Tlatelolco, a suburb of his beloved Mexico City, with its "streets, well-planned houses, shops, fountains . . . something to lift the spirit by appealing to the senses. This villa," concluded the urbane friar, "is the exact opposite, for in the final analysis it lacks everything." [11]

That of course was glib and unfair. Father Domínguez did not have to hold the missions of New Mexico up to the architecture or the orthodoxy of the big city to show that there were problems. If his judgments, like those of an Old Testament prophet, were harsh and a source of mortification to his superiors, they were also well founded. Subsequent ecclesiastical visitors, particularly those from the diocesan see of Durango, would find even more to condemn. Trouble was, they could do little else. The Church, increasingly beset in the years after 1776, was in no position to carry out reforms of substance in marginal New Mexico. Still, the occasional visitors kept coming. And if they could not cure the disease, at least they kept damning the symptoms. NEGLECT By the early nineteenth century the church in New Mexico had become for a majority of New Mexicans a church without clergy. That condition of neglect, more than any other, gave it its special character. Back in 1776 the settled population of the province, counting the El Paso district, stood at about 22,500. Ministering to the lot were twenty-nine resident Franciscans, eight of whom Father Domínguez described as old or ill or both. Another was blind. Seven more he judged unworthy because of scandalous behavior. That left only thirteen fit ministers, or one for every 1,700 souls. By 1818 New Mexico's population had all but doubled and settlement had spread out along the tributaries of the upper Rio Grande and into the valley of the Pecos. Now there were five secular priests of the diocese and twenty-three Franciscans, most of whom, according to the bishop's visitor, were the dregs. The Franciscan Order, to hear Juan Bautista Guevara tell it, had been using New Mexico as a dumping ground for unruly and depraved friars. The results, he said, were deplorable. A third of a century later, in 1851, stiff young Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy, appointed to the newly created American vicariate of Santa Fe, found neglect he thought worse than deplorable—only a dozen or so "incapable or unworthy" priests for the spiritual nurture of 68,000 Catholics strewn over an area as big as all France! God have mercy. [12] Because there never were diocesan priests enough, or because they did not care to serve in impoverished New Mexico, the Franciscan ministry had been allowed to wither on the vine. As the mother province in Mexico City felt the searing winds of turmoil and change, of revolutions, Napoleon, and independence, of liberal attacks on church privilege and property, the flow of replacements and supplies slowly dried up at the source. In the field Governor Juan Bautista de Anza, noting the ghastly toll of Pueblo Indians carried off by smallpox in 1781, managed to cut back the number of government subsidies to missionaries. In 1804 Governor Fernando Chacón accused the friars of gouging the poor citizenry and of turning their backs on the Pueblos because the authorities had forbidden them to discipline their charges or put them to work. But who else was there to administer the sacraments? [13]

So they stayed on, sustained as providence would have it by inertia. When Pedro Bautista Pino, New Mexico's lone voice in the Spanish Cortes of 1810, renewed in vain the old bid for a diocese of Santa Fe, he urged that the seminary faculty as well as the first bishop be Franciscan. The people, said Pino, had grown so used to the friars' blue habit that they were not likely to welcome a change. One by one the friars died. When in the mid-1840s hard-pressed Bishop José Antonio Laureano de Zubiría of Durango requested more Franciscans for New Mexico, only one came. Fray Mariano de Jesús López labored alone from Isleta to Zuñi, "a Superior without subjects," and in 1848 when, according to one version, an old musket blew up in his face, he died. Juan de Oñate's donation of New Mexico to the Franciscans "for all time" had lasted precisely a quarter-millennium. [14] The dearth of priests manifested itself in a hundred ways. Children were baptized only "at the cost of a thousand hardships." Lovers did without the sacrament of marriage and raised families in sin. The sick died without confession and their kin improvised the burial office. Mass was a rare occasion. A priest came only a few times a year, but the collector of tithes never missed. "How resentful," thought attorney Antonio Barreiro in 1832, "must the poor people be who suffer such neglect." Resourceful might have been a better word. Cut off as they were from benefit of clergy they came to rely for community social services and religious expression on their own brotherhoods of charity, devotion, and penitence. Naturally there were deviations from canonical practice, abuses which the socially conscious young attorney did not dare describe and which Bishop Zubiría sought to correct. "I prohibit those brotherhoods of penitence, or rather butchery, that have been growing in the shelter of an inexcusable tolerance." The first bishop to visit New Mexico in seventy-three years, Zubiría might as well have outlawed the adobe. At this stage it would take more than godly admonition. [15] The earth-walled chapels the settlers built in their mountain valleys looked like small versions of every other church in New Mexico. As such, they shared the derision of outsiders. "Quaint little buildings," George Ruxton called them, "looking with their adobe-walls, like turf-stacks. . . . really the most extraordinary and primitive specimens of architecture I ever met with." [16] They decorated them inside with their own religious art, their own stiff, agonizing santos. Conceived without the urging of a priest, licensed hit-or-miss from Durango, these isolated chapels so proliferated in the years after Domínguez that they soon outnumbered the missions. As for the larger villa and mission churches, they seemed to have fared as well during the era of neglect as before. Barreiro only betrayed his Mexican origin in 1832 when he wrote that the churches of New Mexico were "in a state of near ruin." Certainly at any given time one could find leaking or partially fallen churches, even Santa Fe's parish church in 1798. Still, leaking or not to the uninitiated these adobe buildings always looked ruinous.

With or without priests, the people, moved by such devout and public-minded citizens as don Antonio José Ortiz, raised up fallen walls, put on new roofs or towers, restored baptisteries and sacristies—all in good time. Neither technology nor economics allowed them much variation in style, although by the 1830s and 1840s the influence of the Santa Fe trade could be seen around the capital in the three-tiered tower of San Miguel chapel and the clock on the face of the parish church. The buildings that did suffer for lack of maintenance were the mission conventos. Without friars living in them it hardly seemed worth the trouble. It was the ill-furnished and dirty church interiors that most disgusted the squeamish visitador Guevara. Reporting to the bishop in 1820 Guevara, always eager to cast the Franciscan regime in a bad light, deplored

Despite the ever-present swallows and the want of clergy, fewer of the churches of 1776 were lost to neglect than to the quest for progress that followed. PROGRESS

Had Jean Baptiste Lamy had it all his way, there would not have been an adobe church left standing in New Mexico. They were lowly, obscene, utterly lacking in architectural character, like the stable of Bethlehem, which ought to have given him pause. But Lamy, a peasant himself, newly elevated to the awesome aristocracy of the Church of Rome, dared not look to his own earthy origin, but rather, in Paul Horgan's words, to his "memory of the high architectural art whose tradition he had inherited . . . . Byzantium and ancient Rome would still speak through him." Above all, he saw himself as a civilizer, a bringer of orthodoxy to benighted folk Catholics. It was a vision and a burden he shared with his predecessors. But with Lamy it was different. When Domínguez disparaged the religious art of Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, and Guevara censured rude saints on animal hides, and Zubiría fulminated against the Penitentes, they were hardly in a position to follow through. Lamy was. He had come to stay. Moreover, Lamy was a foreigner. From his native France he recruited priests and begged alms. From France he drew inspiration. Pointed windows, spires, and gabled roofs, louvers and botonée crosses—how much more seemly than anything he found in New Mexico. And, as an adjunct to U.S. occupation, the first bishop of Santa Fe presided during a period of unprecedented immigration, commerce, and technology. If he could but raise the funds, Lamy would raise to the glory of God much more than a "stable of Bethlehem." [18] It is fashionable in our day to berate Lamy and his Frenchmen for their callous disregard of Pueblo and Hispanic culture in general and of indigenous architecture in particular. But conquest is like that. It could hardly have been different, and perhaps worse. What would have resulted, let us imagine, had the Anglo-Irish American hierarchy appointed an O'Shaughnessy to the new see of Santa Fe? [19]

No one accused Bishop Lamy of sloth. By 1866, after fifteen years, he had schools and nuns and the beginning of a seminary. He had fifty-one active priests, thirty-one of them Frenchmen. They had repaired many of the old churches, he told the fathers in Rome, and had built eighty-five new ones, all of adobe, which was, after all, cheap. Initially most repairs to the historic earthen churches, including his poor "cathedral" in Santa Fe, were routine. Soon, however, as resident pastors returned to some of the missions, the era of earnest remodeling began. They would punch new windows through the adobe and greatly enlarge old ones. They would put up wooden belfries of milled lumber and gabled "tin" roofs that totally eclipsed the characteristic clerestory light and made these buildings look more like barns than churches.

But the pitched roofs were not all bad. When well built, with adequate overhang and drainage, on structurally sound adobe walls, they lasted longer with less maintenance than the flat earth roofs. They shed water rather than absorbed it. Granted, the walls beneath had to be properly tied by beams across the structure's width to keep the weight bearing straight down and not pushing the walls outward at the tops. In most cases the old flat roof, repaired as necessary, was simply left in place and the new gabled one put up, like an umbrella, over it. So it was at Isleta, where renovators removed the pitched roof in 1959, and at San Felipe Neri in Albuquerque, where for more than a century a similar covering has preserved what lies beneath. But because the historic mission churches at Nambé and Santa Clara collapsed in heaps soon after receiving pitched roofs, such roofs have been damned ever since—unfairly. Men, not materials, were to blame. Contrary to what the hasty remodelers believed, it took more than a pitched roof to cure a sick building. If they had carefully repaired the cracked and sagging walls at Nambé and Santa Clara, and tied them securely, new roofs would not have brought them down. Neither were the pitched roofs all ugly. True, they took some getting used to. At Santa Cruz de la Cañada, largest of the eighteenth-century colonial churches, the massing of the great multilevel superstructure, which overspreads not only the body of the building but both side chapels as well, is surely a triumph of folk architecture and, to those who will behold, a thing of beauty. One blessing of the new era was graphic. In word and picture Anglos tended to portray the strange earth-built temples as salient features of the New Mexican scene, often with a strong Waspish bias. In the train of military and scientific expeditions came keen observers and artists, the likes of Lieutenants J. W. Abert and John Gregory Bourke, and then the early photographers: Nicholas and W. H. Brown, George C. Bennett, John K. Hillers, Ben Wittick, William H. Jackson, Adam Clark Vroman, and the rest. Their work provided a more reliable record than ever before, albeit one of decline, alteration, and collapse.

The graphically documented case of San Juan is an extreme example of what could happen, given an enduring French priest and extraordinary means. Father Camille Seux of Lyons, ordained by Lamy in 1865 and assigned to San Juan pueblo in 1868, unlike most of the immigrant priests, had money. In 1888 at his own expense he had a life-size Our Lady of Lourdes shipped from France and erected in the center of the plaza on a lofty stone pedestal. Two years later it was a $10,000 Gothic chapel of stone which sprang up like a misplaced fleur-de-lis across the road from the church. Next he remodeled the church itself until, with pitched roof, rose window, and pretty French steeple, it stood wholly unrecognizable. The two-storied parish rectory was up by 1898. And finally, in 1912, the venerable Seux had San Juan's faulty old church condemned to make room for a "pseudo-Gothic" red-brick structure with wooden floors, marble altars, and stained-glass windows. [20] A similar fate, meantime, had befallen the antiquated parish church in Santa Fe, entombed as Lamy's labored "Romanesque" cathedral went up around it, then pulled down, carried through the front door, and hauled off in wagons. And no one objected. Adolph Bandelier, who went into ecstasy over cliffs or mounds containing Indian antiquities, looked down his nose at the less ancient adobe churches. They were, he said in his Final Report,

To Lieutenant Bourke, Bandelier's contemporary who sketched nearly all the pueblo churches, "the loveliest piece of church architecture in the S.W. country" was the chapel at the Loretto convent in Santa Fe, modeled after the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. Here was an expression of true culture in a land that contrasted so curiously with progressive nineteenth-century America. "It afforded me," wrote Bourke,

On one occasion Bishop Lamy found a use for his "mouldy" mission churches—as historical record. In an unsuccessful effort to gain church control of the Pueblo Indian agency and win public school funds for Catholic teachers under the policies of the Grant administration, Lamy wrote to General Charles Ewing of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, citing the weight of archives, oral tradition, and

Now and then, as in the previous two hundred years, one of the old churches cheated the remodelers. It fell down. Or it was pushed. U.S. Army howitzers, vandals and modernizers, fire and flood—each added to the toll. By the early twentieth century, however, a small, ardent, and very vocal minority was rallying around the surviving churches. The remodeler was about to meet his match—the historic preservationist. MISSIONS AS MONUMENTS A hundred years after Juan Bautista Guevara likened the missions of New Mexico to the cellars of pulque parlors, another outsider, a transplanted painter of seascapes from California via New York, stood enraptured. These structures, exulted Carlos Vierra, possessed

Nowhere was the fated clash of preservationist and remodeler more clearly drawn than at Cochití pueblo. In 1900 Archbishop Peter Bourgade invited the Franciscans back to New Mexico, Austrians most of them, from the Cincinnati Province. They took over first the parish of Peña Blanca with its Indian missions of Santo Domingo, San Felipe, and Cochití. Although it already looked old, Santo Domingo's church was new and solid. The eighteenth-century structure at San Felipe, a favorite of the preservationists, stood in tolerably good repair. In contrast, Cochití sagged and looked unsafe. Writing in 1916 in a Franciscan house organ, which proudly displayed before and after photos, Father Jerome Hesse told of "embellishing the church" at Cochití.

"Benevolent vandalism," Vierra called it. This "splendid mission church, with its striking exterior gallery and balustrade," lamented Paul A. F. Walter, "was transformed recently into an execrable little mud chapel, with [California] mission arches of spindly thinness marring the front." The tall "New England steeple (of tin)" was the final indignity. The Franciscan in charge, said Walter, had disclaimed responsibility, protesting that it was the young Cochitís just back from government schools who "simply insisted upon having a 'modern' church." [26] Not until the 1880s, that romantic decade of Helen Hunt Jackson and Charles Fletcher Lummis, had Anglos in New Mexico awakened to the charm and the marketable attraction of their Spanish antiquities. Roused by the Christian Brothers' threat to tear down decrepit San Miguel in 1883, the Santa Fé New Mexican Review ran an article subtitled "An Historical Feature Which Santa Fe Cannot Afford to Lose." A year later the paper published an appeal for funds to save this tourist mecca. "Visitors of religious creeds, without distinction, or without respect to political opinions, have urged the restoration of this ancient relic, and have, again and again, expressed their surprise that nothing was done for the purpose." Surely the public could not stand by and let "fall to utter ruin the venerable pile reared to the worship of the Almighty three centuries ago by the cavaliers and missionary priests of Spain." Archbishop Lamy and Governor Lionel A. Sheldon cosigned a brief statement warmly endorsing the project. [27] They did save San Miguel. But despite the sympathy of a group calling itself the Society for the Preservation of Spanish Antiquities in New Mexico, former Governor L. Bradford Prince in 1915 deplored "the rapid destruction of these monuments to missionary zeal." It was evident to him "that if the memorial of the ancient missions was ever to be written, or even their pictures preserved, it must be done at once." His Spanish Mission Churches of New Mexico, the first such compilation, was a creditable job.

The Society, too, was Prince's idea. A certificate of incorporation, dated January 15, 1913, and signed by seventy-two notables (thirty with Spanish surnames), set forth its object: "the protection and preservation of churches, buildings, landmarks, places and articles of historic interest connected with the Spanish and Mexican occupation of New Mexico." Its letterhead showed Prince as president; Archbishop John Baptist Pitaval, honorary president; Benjamin M. Read, secretary; Félix Martínez, vice-president; Bronson M. Cutting, vice-president; Antonio Lucero, treasurer; fifteen additional members of the board of governors; and nineteen county vice-presidents. But the organization hardly functioned. Father Barnabas Meyer, O.F.M., sought aid in preserving the ruins of church and convento at Giusewa near Jemez Hot Springs, and Father Fridolin Schuster, O.F.M., explained to Prince the need for repairs at Ácoma. Had not the Great War intervened, something might have been done. But here was a precedent. [28] Already the aura of mission and pueblo was inspiring the so-called Santa Fe style of architecture, "the kind," said the New Mexican, "so much admired by the artists and people of artistic temperament who come here." Actually, hard-headed businessmen, not artists, had launched the promotion. Even before the end of the nineteenth century, President Edward P. Ripley of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company had grasped the potential of hotels and stations rendered in the charm of regional architecture. At first that meant only one thing, California Mission style, which accounted for Albuquerque's gracious Alvarado Hotel and the Los Chavez at Vaughn. Then, with the construction in 1909 of El Ortiz, the Fred Harvey Hotel at Lamy designed by Kansas City architect Louis Singleton Curtiss, the Santa Fe style made its railroad debut. [29] Catchy as it is, the phrase "Santa Fe style" is a misnomer, at least in terms of origin and earliest expression. In truth, the Pueblo-Spanish colonial "revival" visited philistine Albuquerque before it settled in cultured Santa Fe. Its unlikely agent, a thirty-six-year-old, Ohio-born geologist named William George Tight, stepped from the train at Albuquerque in 1901 to assume the presidency of the infant University of New Mexico. For eight years, until the Regents fired him, the broad-minded, enthusiastic, genial Dr. Tight dedicated himself to the advancement of the school. It was he who conceived of a university pueblo, "a new-old style which would make the University of New Mexico absolutely distinctive in college architecture the world over." [30]

Impressed by his visits to Indian pueblos and by the archaeological report of Jesse Walter Fewkes on Sikyatki and other Hopi sites, Tight got together with faculty member and part-time architect Edward B. Cristy and mapped a radical building campaign for UNM. They would use conventional brick but cover it "with a coat of rough cement that exactly counterfeits the stone-adobe construction of the original pueblos." First off the drawing board was the central heating plant, a substantial flat-roofed structure with stepped-up profile, corner buttresses, and handsome second-story porticoes. Built in 1905, remodeled beyond recognition over the years and demolished in 1979, this house for furnaces and boilers seems to have been the first expression in New Mexico of modern "Santa Fe style," or, as Tight preferred, modern "Pueblo style." [31] The Estufa, a fraternity meeting house modeled on a Rio Grande Pueblo kiva, two dormitories named Hokona and Kwataka after Hopi deities, and the president's house—these erected by the end of 1906—gave the desolate campus a look all its own. In 1907 the national news magazine The World's Work featured an illustrated article by E. Dana Johnson entitled "A University Pueblo, A Reproduction by the University of New Mexico of an Ancient Indian Pueblo, Adapted to College Uses." The author stressed that the model was an ancient Indian pueblo, "not the modern pueblo of Arizona and New Mexico, with its mixture of Spanish types," but then admitted that "the capitals of some of the wooden pillars" in the dormitories were "copied from those of the old San Miguel church in Santa Fe and the heavy wall but tresses are in evidence." The beehive oven on the roof of each dormitory concealed a tank "whence water runs through a novel sun-heater which heats the water for the bathrooms below." In 1906, no less. The Tight-Cristy master plan for UNM was as ambitious as it was original.

When the red-brick administration building, called University Hall (today's Hodgin Hall), poorly designed in the Richardson Romanesque fashion and erected with top-heavy hip roof in 1892, was pronounced unsafe, President Tight wasted no time. Since it had to be remodeled anyway, why not in pueblo style? In 1909 the metamorphosis occurred. At the same time, adjacent on the north, a new auditorium, Rodey Hall, went up. Cruciform in plan and said to have been modeled on the church at Ranchos de Taos, here was the earliest "New Mexico mission church" built for secular use—eight years before the art museum in Santa Fe. A mix to be sure, Tight's pueblo university was thoroughly regional. Those who shared his vision were ecstatic. Ramón Jurado, writing in the June 1909 Technical World Magazine, called it "the most remarkable campaign of building ever undertaken by any individual or corporation since white men came to the New World." Trouble was, most of Albuquerque wanted to be as up-to-date as Kansas City or Philadelphia. The townspeople failed to see the progress in turning a respectable university building into an Indian pueblo. "If you are going to be consistent," suggested one, "the President and faculty should wear Indian blankets around their shoulders, and feathered coverings on their heads!" [33] The Regents agreed. Dr. Tight was moving backward too fast. Besides, he was too liberal, too independent. Dismissed without warning in 1909, William George Tight died the following year. Although the idea of a pueblo university was never entirely discarded, building at UNM proceeded haphazardly. When Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin, designer-elect of Canberra in Australia and a visitor to Albuquerque in 1913, submitted a master plan for UNM in 1915, he described his Mayan-inspired proposal as "a compact, continuous pueblo . . . . low-lying with economical plain masses." But Griffin got tied up in Australia, his associate Francis Barry Byrne drew a very plain Chemistry Building, and that was that. [34] Not until 1927 did the Regents finally vote to adopt the local pueblo style after all. That cleared the way for architect John Gaw Meem's masterful buildings of the 1930s. Tight, whose vision had cost him his job, was vindicated. Meantime, in Santa Fe, work crews under archaeologist Jesse L. Nusbaum had subjected the old governor's palace to a conspicuous "earlying up." Completing the job in 1913, they had traded a real "Victorian" portal for a conjectural Spanish colonial one. While most preservationists today think it was a mistake, the remodeling of the palace did set in motion the "Santa Fe style" in the city that gave it its name.

In the fall of 1913 the Santa Fe Chamber of Commerce sponsored a contest offering prizes for the "best design of a Santa Fe Style residence not to exceed $3500 in cost." Historian Ralph E. Twitchell, by his own admission, boldly conceived New Mexico's stunning entry in the Panama-California Exposition at San Diego in 1915, "capitalizing sentiment rather than pumpkins and pigs." The result was a distinctive building, designed by architects I. H. and W. M. Rapp, and modeled on the church and convento of Ácoma with features from several other missions thrown in. The Art Museum in Santa Fe, a similar monument in imperishable brick, dedicated in 1917, plus promotion by an avid circle of preservationists that included archaeologists Edgar L. Hewett and Sylvanus G. Morley, won for the style widespread acceptance. Public buildings, warehouses, gas stations, and some of the best residences resulted. And all this, chortled Twitchell, over the opposition of selfish contractors and builders who wanted "to bring to Santa Fe the modified Hindubunga low, so popular in southern California." [35] This was no architectural revival in the traditional sense, no resurrection of a dead but admired style. Rather it was a case of the immigrant Establishment going native. The Pueblo-Spanish colonial style had never died out. It had gone right on crumbling and being renewed in New Mexico's pueblos, villages, and old towns. Once its charm had been endorsed by the university, the railway, and the bank, once modern plumbing had been installed along with choice Navajo rugs and San Ildefonso pottery, those who embraced the style felt smug and very much a part of the cultural ambience.

As the cult matured it was only natural that its devotees should move to protect their shrines. At the request of Father Fridolin Schuster, the preservation-minded Franciscan pastor of Ácoma and Laguna, the Museum of New Mexico in 1920 sent a man to Laguna to inspect the church. Its need for a new roof came to the attention of Miss Anne Evans of Denver, patroness of the arts and frequent visitor to New Mexico. In 1922 Denver architect Burnham Hoyt, Carlos Vierra, and Miss Evans, with the full cooperation of the Museum, extended the structural survey to other missions and estimated the cost of repairs. Evans hastened back to Denver to raise funds. Meantime, a committee had been formed, a happy combination of the expert and the monied. Its chairman was none other than the newly elevated sixth archbishop of Santa Fe, Albert Thomas Daeger, a thoroughly acculturated Franciscan whose ministry in New Mexico dated back to Peña Blanca in 1902. Laguna got its new roof. Zia was next. By the end of 1923, thanks to the technical assistance and dollars supplied by the committee, that church had a thoroughly modern roof embodying tar, concrete, chicken wire, and asphalt, yet looking "just as if it had emerged from the hands of the Francis can Fathers of old." That was the ideal: to strengthen the fabric without altering the traditional appearance.

The committee had a name, a long and descriptive one that rarely appeared in print twice the same way—The Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of the New Mexican Mission Churches. Its greatest challenge, repairs to the mammoth temple on the rock of Ácoma, commenced in 1924 with the heroic laying of a concrete-slab roof in six weeks. In succeeding seasons field crews under B. A. Reuter renovated badly eroded exterior walls, restored the south tower, and rebuilt the twin adobe belfries. Work at Santa Ana and Las Trampas followed. Although the committee itself did not long outlast the double calamity of the Depression and Archbishop Daeger's fatal fall into a coal cellar in 1932, its young architect in the field did. For the past half century there has been no more tireless advocate of New Mexico's unique regional architecture than John Gaw Meem. [36] Ruined churches, too, exercised the preservationists. In 1909, the same year the Museum of New Mexico was founded and given the run down Palace of the Governors, President Taft had proclaimed Gran Quivira a National Monument by authority of the Antiquities Act, a law conceived by the Museum's director, E. L. Hewett. Eventually three other stone relics—Abó, Quarai, and Giusewa—and one of adobe, Pecos, came under New Mexico's protection. Hewett, who looked upon ruins with an almost mystical reverence, pressed for excavation and stabilization. For years he preached preservation. Then in the 1930s, during "the search for projects on which to expend federal funds," some of his disciples suggested restoration. No, cried Hewett

During the 1930s the traditional religious architecture of New Mexico was legitimized in draft, word, and deed. In 1934 the Historic American Buildings Survey, assisted by John Gaw Meem, made the first complete measured architectural drawings of the adobe churches at Ácoma, Laguna, and San Miguel, all stepped off by Domínguez in 1776. It also charted the later ones at Ranchos de Taos, Talpa, and at El Potrero where the famed Santuario de Chimayó had been purchased and restored to the archdiocese in 1929 through the efforts of Mary Austin and a donation of $6,000 from an anonymous graduate of Yale University.

In the mid 1930s, too, a bright, persistent Yale student began poking around the missions taking notes and photographs. George Kubler meant to set this unique architectural manifestation in the greater context of Western Civilization. His doctoral thesis, published in 1940 as The Religious Architecture of New Mexico, became the bible. New churches, meanwhile, went up in the old style, most of them designed by Meem, from Father Agnellus Lammert's landmark on the hill at McCarty's, a fond sight to passengers on the Santa Fe, to the classic Cristo Rey, built as New Mexicans celebrated the Coronado expedition's four hundredth anniversary. Since then scholarship, preservation, and building have progressed apace. The highlight in historical documentation was the 1956 appearance in print of Father Domínguez's unequaled word pictures of 1776, the happy collaboration of Eleanor B. Adams and Fray Angelico Chavez. In archaeology the prize went to Jean M. Pinkley of the National Park Service, who, in 1967, discovered at Pecos an architectural surprise that had eluded Domínguez, Bandelier, and Hewett. The preservationists won some and they lost some. Despite the admonition of Vatican II that historic structures and art be cherished, the momentum of liturgical renewal caused a drastic remodeling of the Santa Fe Cathedral's sanctuary and a plan to reconstitute San Felipe Neri in Albuquerque. It took the intervention of the Secretary of the Interior to avert a near collision of the road with the church at Las Trampas. Flat roofs went back on the mission churches of Cochití, Isleta, and Picurís. At Zuñi the National Park Service directed the excavation and reconstruction of a historic church, while a new one with an old look rose at San Ildefonso. Federal Bicentennial funds bought a facelift at Sandía and aided the rehabilitation of Guadalupe in Santa Fe. Today, even as the annual revelation of Ash Wednesday is proclaimed again in the churches—for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return—the quest goes on for that fabled elixir of life, the foolproof adobe preservative.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||