|

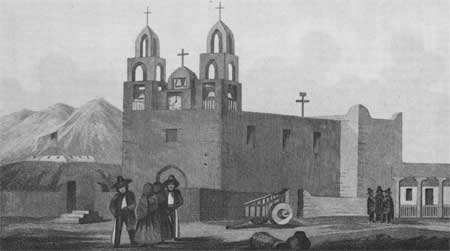

Santa Fe SAN FRANCISCO, LA PARROQUIA But for the rigors of reconquest, and the uncordial relations between don Diego de Vargas and the Franciscans, the Parroquia might have been the oldest. As he bided his time at El Paso in 1693 and thought of restoring Santa Fe after thirteen years of Pueblo Indian occupation, Vargas had vowed to build first a new parish church. There he would enthrone the three-foot-high statue of Nuestra Señora del Rosario, La Conquistadora, heavenly patroness of the reconquerors. But he did not, and La Conquistadora found herself in the governor's palace, a patient lady in waiting. Meantime, in 1697, don Pedro Rodríguez Cubero, Vargas's replacement, ingratiated himself with the friars by having a proper convento built for them at his own expense. Not for another twenty years, however, did the promised Parroquia go up alongside. Under construction between 1713 and 1717, it faced west toward the plaza just in front of where the one demolished by the Indians during the Pueblo Revolt had stood. Off the north arm of its transept grew a chapel, really a miniature church complete with choir loft, nave, sanctuary, and sacristy. Here La Conquistadora finally came home. [2] Except for its convento, Santa Fe's church of Saint Francis looked sound enough to Domínguez in 1776. Less than twenty-five years later it collapsed, or a part of it did. Instinctively the faithful turned to don Antonio José Ortiz, New Mexico's most generous church benefactor, "a pious old wealthy citizen of Santa Fe." The death of his prominent father at the hands of Comanches in 1769, and the general plight of the province back then, had sparked new devotion to La Conquistadora. Don Antonio José was a leading member of the religious society, or confraternity, bound to do her honor. Among his previous good works was the Parroquia's new San José chapel, extending from the south transept and balancing, as it were, the Conquistadora chapel on the other side. A routine inventory in 1796 listed the Ortiz donation "with its new altar screen, and very well adorned." Writing to the bishop of Durango in 1804, Ortiz congratulated himself for having undertaken the rebuilding of the Parroquia "after it had fallen down the first time, six years ago." By 1803, thanks to him, its walls were back up ready for the roof. Then lightning struck, or at least a fearsome storm. As a result, the devout New Mexican related, "I was obliged to tear it down again and enlarge it ten varas." He had already renovated the sanctuary and both auxiliary chapels. The nave walls stood in 1804 only four courses of adobes short of receiving the roof vigas. So far the job had cost Ortiz 5,000 pesos. This time the roof went on, and the twin bell towers sixteen and a half varas tall. Before Antonio José Ortiz died in 1806, just shy of his seventy-second birthday, he had the pleasure of seeing New Mexico's principal church back in service. [3] While all this was going on, the convento, an enclosed square abutting the church on the sheltered south side, underwent one repair job after another. Not a year old in 1776, the second story with its spindly vigas looked to Domínguez "already on the point of falling." The cursory inventory of twenty years later described the structure as "a closed half cloister with its porter's lodge; two quarters for two ministers, corresponding workrooms and kitchens, with their doors and locks; its cloister patio with two apricot trees; a second patio with stable, back gate, wall, and the rest; everything in a state of ruin." Thoroughly fixed up in 1800, most of its twelve rooms by 1814 were again substandard. By definition a cathedral is any church, grand or not so grand, in which a bishop has his cathedra, or chair. Pedro Bautista Pino's futile plea in 1812 for a diocese of Santa Fe did raise again the prospect of the Parroquia as cathedral. But was it suitable, the authorities wanted to know. In an effort to let them judge for themselves, Governor José Manrique in 1814 ordered a detailed description of the physical plant. Obviously cruder in workmanship than it had been in Domínguez's day, it was also a bit larger. [4] The structure's size, however, was not the problem. What sorely exercised ecclesiastical visitors from Durango was the dirt, the birds in the sanctuary and the mice in the vestments, the improper confessionals and holy water pots, the threadbare altar linens, and the vulgar objects of worship. "You will obliterate entirely the image of Santa Bárbara painted on elk hide" charged the irate Juan Bautista Guevara in 1818, "and remove it as indecent for veneration." None of the church exterior was white washed, noted don Agustín Fernandez San Vicente in 1826. Worse, the cemetery, contained in an irregular-shaped yard in front of church and convento and extending all along the north side, was a disgrace. No cross stood in the center as it should. The walls had crumbled in places. All the gates were off, presumably because new ones were being made. Without them, Fernandez noted, "animals can easily get in and foul themselves in it, invading without due respect the graves of the cadavers that lie within. These, after all, were once living temples of God." [5] What struck His Most Illustrious Lordship don José Antonio Laureano de Zubiría, bishop of Durango, about Santa Fe's "mediocre and largely impoverished" churches in 1833 was how much worse their condition would have been but for Juan Felipe Ortiz, his vicar general. A grandnephew of rebuilder Antonio José, don Juan Felipe as pastor of the parish church had seen to repairs. [6] The very nature of a mud-built temple demanded as much. "The material of this entire fabric," read the 1814 assessment, "is adobe and its construction without the slightest rule of architecture, built by rude artisans. As a result, given its perishable nature, it cannot last without continual repair, as is all too evident." In the summer of 1846 as the U.S. Army of the West advanced on Santa Fe, word of the New Mexicans' state of fear and confusion grew louder. Such reports were good for morale. "An American gentleman has just arrived in camp from Santa Fe," an officer noted in his diary.

When finally the wide-eyed U.S. troopers did march into town, they could not believe it. This was the capital, the mecca that had given name to the Santa Fe Trail? Most of the invaders saw the adobe villa and its inhabitants disdainfully through Anglo-Saxon Protestant eyes. A few were trained observers and artists. Youthful J. W. Abert of the Topographical Engineers glimpsed beauty where his fellows did not.

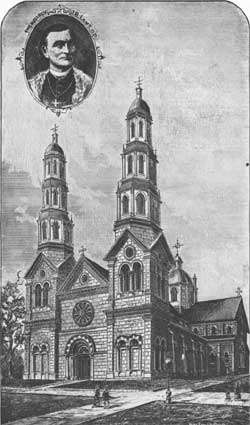

Vicar Juan Felipe Ortiz, Bishop Zubiría's man in Santa Fe, "a large, fat-looking man," was comfortable and entrenched. He had no desire to surrender his allegiance or his parish. In fact from 1851, the year Jean Baptiste Lamy first appeared in Santa Fe as prelate, until early 1858, when Ortiz died, he caused the stiff Frenchman no end of headaches. For a time Bishop Lamy, sorely offended by Ortiz, took his cathedra and moved over to the renovated Castrense. Only when Ortiz set off for Durango in a huff did Lamy return to the Parroquia. The new bishop had little time to sulk about his adobe cathedral, however much he despised it. Writing to his French backers some five years later, he admitted his hope for "a new church that would look more like a cathedral than the present one." He considered the historic Parroquia graceless and very poor, and who, having known Notre Dame de Paris, would not? "Bishop Lamy," the New Mexican reported in 1868, "is making some much needed improvements around the ancient church of the Parroquia in this city." Actually he was clearing the area outside its walls. The following year he watched with satisfaction the laying of a ceremonial cornerstone, a genuine block of smooth-cut native stone. A hollow within contained the names of President Grant and other contemporary officials, as well as coins, sundry documents, and newspapers. Three days later "some miscreant, for the sake of lucre," stole it. No matter. The project was launched. [9] The outward appearance of the patched old Parroquia had changed notably since Abert first sketched it back in 1846. For one thing the entire roof line, including the towers, transept, and side chapels, now featured neat castlelike crenelations. Certainly there were precedents in New Mexico. Eighteenth-century documents spoke of almenas, or merlons, the solid parts between the open creneless. Once revived, they proved contagious. San Miguel in Santa Fe and San Felipe Neri in Albuquerque caught them and Santa Cruz de la Cañada had a variant strain. Abert had shown a clock set in the pediment between the towers, evidently an ingenious one attributed to Josiah Gregg. When it struck, the figure of a little Negro came out and danced. But soon it quit, so the story goes, because the priest failed to pay Gregg the full price. Later that clock came down, for photographs made in the mid-1860s showed a statue niche instead. By 1868 a new clock and a new pediment appeared. [10] The plan was to go on using the Parroquia even as the masonry walls of a seemly "Roman Byzantine" or "Midi-Romanesque" cathedral went up around it. After an Anglo architect, who plainly "did not understand the work," botched the foundations, Lamy imported Frenchmen, and by 1873 the stone walls stood as high as the window tops: Lack of funds halted the job for the next five years. Meantime, in 1875, Santa Fe became an archdiocese and Lamy an archbishop. In town during Holy Week of 1881 the insatiably curious Lieutenant John Gregory Bourke attended Maundy Thursday vespers at the church within a church. The Cathedral, "a grand edifice of cut stone," he noted, looked not more than half finished. Bourke's word picture of the adobe Parroquia inside was one of the last.

At the conclusion of the sermon, which Bourke strained to hear over the "epidemic of coughing, hawking, spitting and sniffing," he was surprised to see the archbishop wash the feet of twelve altar boys, "a custom which I have never before seen in this country." [11] After 1878 construction progressed by fits and starts. By the spring of 1884 the Santa Fe New Mexican Review had the end in sight.

By the grace of God, the mammoth towers with three-tiered wedding cake spires, planned all out of proportion to a height of one hundred and sixty feet, have never risen above eighty-five feet. Incomplete and truncated, they are more appropriate to the surroundings, more pleasing. After nearly a century the very thought of adding the spires would cause undreamed-of gnashing of teeth and rending of garments among preservationists. It also would violate the city's Historic Zoning Ordinance. [12] The hot, dirty business of tearing down the entombed Parroquia back to its transept took all the month of August 1884. Wagons lined up out front to receive the debris. The untiring Charles M. "don Carlos" Conklin, perennial Santa Fe County sheriff, supervised the whole dusty operation "simply for God." Wagonload after wagonload was dumped to provide fill for Santa Fe's rutted streets. Even though the venerable Parroquia was gone, it consoled Father James Defouri in 1887 to think that "its adobes and rocks are now doing other public work." [13]

Gone, but not quite gone. The Cathedral had cost to this point $130,000, most of it raised by the tenacious Lamy himself. Its nave, 60 feet broad and 120 feet long from two-toned Moorish arched entrance to beginning of proposed transept, could now be used. With so many competing needs throughout the archdiocese it seemed folly to pursue the costly building, at least just then, "but it will be done," predicted Father Defouri.

Done, but not quite done. When the determined Father Anthony Fourchegu, long-time rector of the Cathedral, completed the present sanctuary section in 1895, he connected new stonework to old adobe and the outer portions of the Parroquia's side chapels, cleaned and restored, became the transept of the Cathedral. The old adobe sanctuary, which still clung to the eastern end, was walled off. Housing the treasured but not indispensable stone reredos from the Castrense it could serve as a "museum." On October 18, 1895, seven years and eight months after death came for Lamy, a softer, better-fed archbishop, Placid Louis Chapelle, at last consecrated this great monument to his predecessor's sacrifice. Because it contained a few humble vestiges of the mud Parroquia, and because its walls, too, were off-parallel by inches, it was not quite as pure as Lamy would have wished. But it was more New Mexican. Ironically, the Cathedral's uncherished adobe limbs almost outlasted its grand and "permanent" stone body. Menacing cracks in vaults and arches began to show up as the heavy walls and columns pressed down on poorly laid foundations. The ground beneath, particularly on the north side, previously disturbed by countless burials, was compacting. The Cathedral was settling. But for tons of iron rods and concrete, applied none too soon during the administration of Archbishop Rudolph Aloysius Gerken, 1933 to 1943, this structure, like its predecessor in 1798, might simply have collapsed. [14] In 1966-67 liturgical renewal, not cracks, brought down all but one relic of the adobe Parroquia. Old sanctuary, sacristy, and south chapel had to go as remodelers opened up the building to the spirit of Vatican II's shared celebration and worship. It would appear that the bones of restorer Antonio José Ortiz, along with those of other prominent New Mexicans buried in the San José chapel, were trucked away in the process of demolition. That something was lost in the remodeling in terms of historical "resources," no one will deny. But who will assess the gain? Meantime, from her throne in the surviving north chapel—all that is left of the Parroquia—La Conquistadora reigns patiently, still New Mexico's favorite Lady. Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||

Top Top

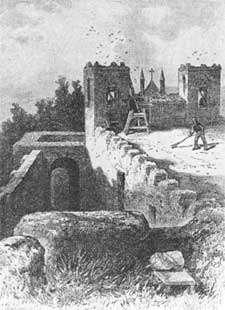

|

| ||||||||||||