|

Santa Fe SAN MIGUEL Rebuilt in 1710, San Miguel chapel owes its existence to the romantic notion that it is much, much older. "With a feeling of awe," confessed Lieutenant Bourke in 1881, "we left a chapel whose walls had re-echoed the prayers of men who perhaps had looked into the faces of Cortés and Montezuma or listened to the gentle teachings of Las Casas." Capitalizing on such feelings of awe, a group of eager boosters staged in 1883 "The Santa Fe Tertio-Millennial Anniversary Celebration and Grand Mining and Industrial Exposition," a spirited six-week-long fair and fiesta in observance, they said, of the city's founding 333 years before. It really did not matter that there were no Europeans in New Mexico in 1550, or that Adolph Bandelier scoffed at "the spurious Tertio millennial jubilee." It was people like Bourke and the Tertio-Millennarians who took notice in the New Mexican of March 8, 1883, that "San Miguel chapel, the oldest house of worship on the American continent . . . is likely to fall and become a mass of ruins at any moment." [28] San Miguel was Santa Fe's left-bank church. As early as the 1620s an ermita, or outlying chapel, of San Miguel had been built for the Mexican Indian servants and others of low station who lived south of the Río de Santa Fe in the Analco section of town. The Franciscans used it as an infirmary. In 1640, at the height of a struggle for power that set Spaniard against Spaniard, raging Governor Luis de Rosas had the ermita torn down to spite the friars. Built anew, presumably on the same site, it became a target of the Pueblo revolutionaries besieging Santa Fe on August 15, 1680. When Governor Antonio de Otermín lamely offered pardon to an Indian emissary, the rebels "derided and ridiculed this reply and received the said Indian in their camp with trumpets and shouts, ringing the bells of the hermitage of San Miguel, spreading destruction among the houses of the district, and setting fire to the hermitage of San Miguel." [29]

But the walls stood. Thirteen years later, in 1693, Diego de Vargas wanted to get La Conquistadora in out of the fierce winter cold by reroofing the little "church or ermita which served as parish church to the Mexican Indians" until 1680. The portions of wall that had weathered away above the windows could be replaced, new roof vigas cut and installed, and the exterior plastered, all in short order. Even while he and his Spaniards were camped outside in the snow, Vargas offered to lend the Indian occupants of Santa Fe mules, axes, and supplies for the job, and he exhorted them to go about building a house for God and His Most Blessed Mother cheerfully. The Indians' decision to fight, rather than evacuate Santa Fe, killed the project. [30]

The rebuilding waited until 1710. It was carried out with the blessings of Admiral don José Chacón Medina Salazar y Villaseñor, Marqués de la Peñuela, who had bought the governorship of New Mexico for the term 1707 to 1712 and fully intended to make it pay. He contributed a token two thousand adobes, which, at the going rate, cost him all of twenty pesos. The prime mover was Agustín Flesores Vergara, royal standard bearer in the governor's household and mayordomo of the confraternity of San Miguel. In October 1709, Flores secured permission of Fray Juan de la Peña, Franciscan superior in New Mexico, to send the confraternity's statue of St. Michael on tour of the colony to raise funds. With its two caretakers it was out most of the winter and returned with commodities amounting to four or five hundred pesos.

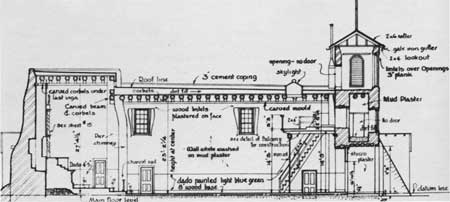

Work began in mid-March 1710 and lasted through most of the building season to the end of September. Sixty-year-old master builder Andr&te;eacus González, a native of Zacatecas who evidently had signed on as a soldier with Vargas back in 1692, oversaw the project. His full work crew, including cook Magdalena Ogama, numbered fourteen. As usual in New Mexico, they were paid in goods, everything from shoes and thread and tobacco to buffalo hides and playing cards. They laid over 20,000 adobes. Wood for scaffolding and for building was brought to the site from various sources. The Pecos Indians, New Mexico's leading carpenters, earned six sheep, overvalued at sixteen pesos a head, for 150 boards and planks. The most impressive single piece of wood in the structure, however, was the hefty crossbeam holding up the choir loft. Ornately carved, it bore the proud inscription, "His Lordship the Marqu&ieacute;s de la Peñuela erected this building [with the aid of] Alférez real don Agustín Flores Vergara, his servant, in the year 1710." [31] Except for at least one roof job in 1760, this was the simple, single-naved building detailed by Father Domínguez in June 1776. He may not have been feeling well. He likened the interior to the granary of an hacienda. Perhaps because the light was so poor he failed even to see the inscription on the Peñuela beam. And he, or his scribe, misplaced on the north side of the structure the long narrow sacristy which stood instead, according to the archaeologists, on the south side. He did not even poke fun at a painting of St. Michael by don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco. Miera, New Mexico's premier map maker, had been lured from El Paso in 1756 by Governor Marín del Valle with the promise of a political appointment. Soldier, rancher, merchant, all-round handyman, don Bernardo also painted and sculpted religious art for the ricos of the province, who in turn donated it to the churches of their choice. Domínguez enjoyed criticizing the work of Miera, who later in 1776 joined him and Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante on their exploration of the Great Basin. Don Bernardo must have painted the canvas of San Miguel before 1760. After that, Marín's chapel and confraternity of Nuestra Señora de la Luz became fashionable, while the chapel and confraternity of San Miguel lost favor. [32]

The punctilious visitor's description in 1818 of a torrecita pequeña de adobe, a little adobe tower, hardly fit San Miguel's unique and precarious five-level tower, a pretentious addition laid up partly against and partly into the facade. Stacked like a child's building blocks, it must have come later, perhaps in 1830 when don Simón Delgado is said to have sponsored a new roof. It was standing for sure in the 1850s when a New Mexican bell caster, one Francisco Luján, who was also "a silversmith and blacksmith, a very industrious man," set about on the grounds of the Parroquia to cast two bells. From the legend on the larger one, "Saint Joseph pray for us," it may be that Father Joseph Machebeuf placed the order. The flawed date, which has given wing since to some romantic flights of fancy, looked more like 1356 than 1856. Not long afterward this squat but sweet-toned bell weighing 700 or 800 pounds was heaved on ropes and poles up into the San Miguel tower. Never sound, the adobe and frame superstructure groaned. At last, in the winter of 1871-72, there blew up a "severe storm and the upper sections of the tower fell with a crash." [34]

Meanwhile, possession of San Miguel church had passed from the patrimony of Vicar Juan Felipe Ortiz to Archbishop Lamy to an order of teachers founded in France by Jean Baptiste de la Salle, the Brothers of the Christian Schools, in whom it has resided since 1859. To the brothers, whose principal business was running a boys' school, the antique church proved something of a white elephant. They did use it as their chapel, wholly renovating its interior "in the style of mid-Victorian taste—coats of house paint on all surfaces and overlayers of neo-gothic wood work." One brother, "in thanksgiving for his improved health," took down the Miera y Pacheco canvas of San Miguel and painted it over with his own rendering in household enamels.

To Brother Paulian, a superior visiting from St. Louis in 1883, the dilapidated church appeared beyond salvation. It should be torn down, before it fell on someone. To make it safe would cost more than the brothers had, maybe $6,000. Brother Botulph, president of St. Michael's College, hoped the citizens of Santa Fe would respond to the crisis. For every contribution of ten dollars, the donor would receive historic photos of the church. "As it is certain," proclaimed the New Mexican Review, "that there is unity of ideals respecting the propriety of preserving this old relic, now, let there be unity of action and the work will be accomplished." By 1888 it was. Two stone masonry buttresses, designed primarily to save the structure rather than complement its uninspiring architecture, thrust up against the facade, wedging the base of the tower tightly between them. The tower now rose straight-sided above the entryway like one big block instead of the former pyramid of graduated blocks, and was not quite so high. [35] With San Miguel thus preserved, the Christian Brothers found themselves keepers of a sacred historic trust. In 1919 when one of them sought to advertise THE OLDEST CHURCH with a giant billboard "clearly legible from the top of the Jemez mountains," the New Mexican shrieked in protest. "Brother, we implore you take it down and put up one that fits the subject and doesn't deface one of America's greatest treasures." He did. [36] In 1955, as the centennial of the Christian Brothers' proprietorship approached, historians, archaeologists, and art conservators swarmed all over San Miguel at the invitation of the genial superior, Brother Francis. It was high time, he reckoned, for some answers. After excavating the sanctuary, testing the walls, and taking datable plugs from its wooden parts, they rendered their verdict. Evidence of an earlier church, undated, lay beneath the floor, but San Miguel as it stood then could claim no greater antiquity than 1710. Isleta, Ácoma, and several other extant churches were older. If that was a blow to the antiquarians, one hundred gallons of paint solvent went a long way toward softening it. Patiently applied to the altar screen, to each of five hard coats of house paint over a four-month period, it slowly revealed the "soft coral pink and sage green" of Antonio José Ortiz's gift in 1798. Skillfully restored by the inimitable E. Boyd, this art treasure is "the oldest dated wooden altarpiece left in New Mexico." Thanks to the unknowing brothers who slapped on the house paint, and thereby preserved it, "the elegance and dignity which a painted wooden altar screen added to an adobe church is best seen at San Miguel." [37]

In July 1972 the playful little statue of St. Michael with silver helmet and sword and outstretched arms—the one carried around New Mexico in 1709 begging alms to build this very church—left his niche again, this time against his will. Stolen, along with the four remaining oval paintings and other religious items, he was gone for nine months. When La Conquistadora was kidnapped from the Cathedral in March of the following year, and recovered with San Miguel and the other objects in an abandoned mine shaft in April, the faithful said that the Lady had gone out to lead Miguelito home. In any case, a $150,000-ransom plot had aborted and two of New Mexico's treasured santos were back on their thrones. [38] The Santa Fe Chamber of Commerce, lineal descendant of the Tertio-Millennarians, and the Christian Brothers, who should know better, still tout San Miguel chapel as "the oldest mission church in the United States." It is not. No matter. The chapel is a prominent feature of the city's Historic District, and its place is secure. Perhaps, too, the triumph of enthusiasm over fact is not always a bad thing. Here at San Miguel in 1883, thanks to the boosters of the City Different, historic preservation in New Mexico had its beginning.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||