|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hikers on the Chilkoot Trail: A Descriptive Report |

|

INTRODUCTION

During the summer of 1976, the Sociology Studies Program sponsored a study of hikers on the Chilkoot Trail, in cooperation with Parks Canada and the National Park Service. [1] This report is a descriptive overview of the results. It consists of a discussion of the statistical findings and a summary of the comments written by the hikers. Included In the report is a brief discussion of the Trail's history and setting and the methodology used. We plan to continue working on the Chilkoot data, analyzing them and pursuing certain topics in greater detail. Results from these efforts will be made available as they are completed. [2]

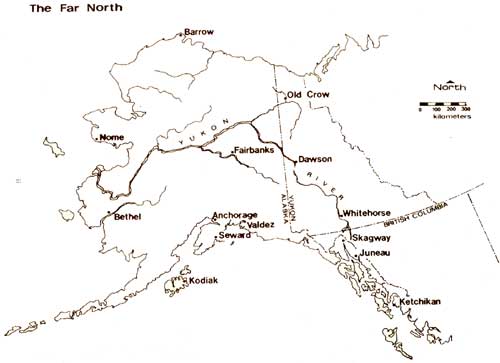

The general purpose of the study of Chilkoot hikers is twofold. First, it provides management with baseline information about the Trail's hikers: their personal characteristics, use-patterns, and opinions. As baseline information, these data not only provide managers with immediate answers regarding their user-population, but also serve as a benchmark with which to compare future use of the Trail. If there is any consistent finding noted within our studies, it is that park-users and their park-going patterns are continually changing. Therefore, In order to monitor this change, to examine the consequences for park management, and to anticipate user-needs, baseline information Is a prerequisite. Second, the Chilkoot study Is one of the first research efforts focusing on backcountry users in the Far North (Alaska and Yukon Territory). We are specifically interested in documenting the existence of a system of backcountry recreation (along with other forms of outdoor recreation) in Alaska. [3]

This study can be considered as part of the growing literature on backcountry (wilderness) use. [4] As such, the Chilkoot study is unique in several ways:

1) It is one of the first extensive research projects on backcountry users in the Far North.

2) It is a study of visitors to a backcountry trail at a time when the Trail came under the management of a new agency.

3) Its units of observation are not only the individual hikers but also the hiking parties .

4) Its methodology includes the universe of hikers rather than a sample of this universe.

History

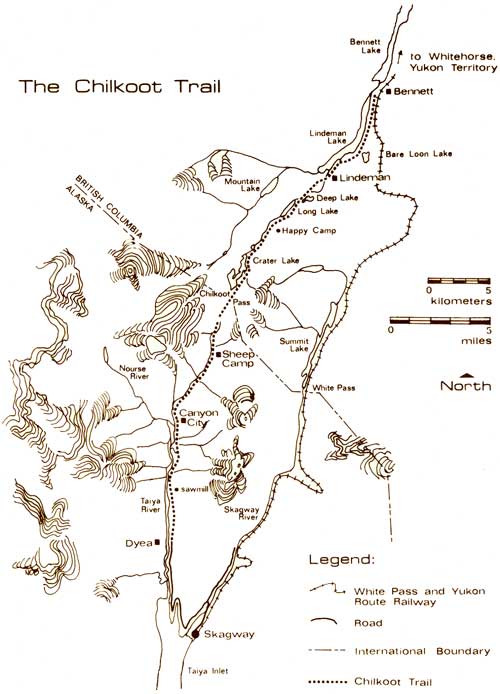

The Chilkoot Trail is a 53-kilometer (33 miles) hiking trail, half of which is located in southeastern Alaska, while the other half is located in northern British Columbia (see the two maps). Historically, it is the route used by many of the stampeders to reach the Klondike gold fields during the Gold Rush of 1898. [5] In August 1896, George Carmack, Skookum Jim, and Tagish Charley struck gold at Rabbit Creek in the Klondike (in Canada's Yukon Territory). [6] In a matter of a few days following the news of this discovery, Rabbit Creek and its south fork, which were to become known as Bonanza and Eldorado Creeks, respectively, were inundated with prospectors. By the winter of 1896-97, word of the gold strike reached the west coast. This sparked the first wave of stampeders, or "cheechakos" as the indians were to call them (meaning "newcomers" or "tenderfeet"), to board steamships heading north to Alaska. The second and largest wave of stampeders began in July 1897 following the arrival in San Francisco and Seattle of two steamships, Excelsior and Portland, from St. Michael, Alaska laden with wealthy prospectors and their KlondIke gold. Newspaper headlines throughout the United States and Canada flashed the news of the Klondike gold strike. In no time, the greatest stampede of gold prospectors ever was in motion.

Numerous routes to the Klondike were available to these stampeders, yet the coastal mountain passes—Chilkoot Pass and White Pass—were the most popular because they were accessible all year round. Once on the west coast, the stampeders boarded any vessel bound for southeastern Alaska and the coastal towns of Dyea and Skagway. Separated by only a few miles of water, Dyea and Skagway vied for the business of the stampeders. Each was the gateway to a mountain pass trail which led to the waterways of the Yukon River. Each provided a staging ground for the cheechakos as they readied themselves for the strenuous climb over the coastal mountains. Each was a boom town populated by transients and at times terrorized by crime, disease, and despair. Thus, a rivalry was born between these two towns and their respective Trails, each trying to outdo the other with the latest in transportation technology and business ingenuity. The Chilkoot Trail was better known, receiving much publicity in magazines and newspapers throughout the world, for the photograph of the human staircase over the Pass made good copy. It was a packers trail where Indians—men, women, and children—were available for hire as packers. Eventually, various tramways were constructed to transport supplies over the Pass. These were built in response to the construction of a wagon road, of sorts, over White Pass. In turn, the White Pass and Yukon Railway Company was established to build a narrow-gauge railroad track over White Pass. By 1900, the railroad was operating between Skagway and Whitehorse, Yukon Territory.

The advent of the railroad signified the demise of the Chilkoot Trail as an efficient transportation corridor. Meanwhile, the Klondike Gold Rush stampede had lost its impetus. Dreams of gold fortunes vanished as discouraged and broken stampeders began to leave the Klondike and return to their homes. Only a few of them managed to secure any kind of a gold fortune. The majority of the cheechakos had only the memory of being a part of the grandest gold stampede in human history as reward for their efforts. Little did they know that the last significant gold find in the Klondike—the kind that made a person wealthy—occurred in October 1897. So by the turn of the century, Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail were abandoned by man and returned to the forces of nature.

Man renewed his interest in the Chilkoot Trail in 1962 when the State of Alaska, through its Division of Lands, Department of Natural Resources, used inmates from the Youth Authority Department and its Corrections Branch to clear and restore the American side of the Trail. In 1968, the government of the Yukon Territory, by arrangement with the government of British Columbia, enlisted its Department of Corrections to restore the Canadian side of the Trail. By 1969, the entire Chilkoot Trail was restored as a recreational trail. Since then, it has been hiked by thousands of people who have enjoyed it both as an historical and backcountry resource. On June 30, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed Public Law 94-323 establishing Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. The American side of the Trail is included as part of this new park. [7] In time, a similar effort by the Canadian government (which will include the Canadian side of the Chilkoot Trail as well as the Yukon River waterway, historical sites in Whitehorse, an historical district in Dawson, and some mined land in the vicinity of Dawson) will complement the United States' newest national park. This larger park complex will be known as Klondike Gold Rush International Historical Park. Today, the American side of the Chilkoot Trail is managed by the National Park Service, while the Canadian side is managed by Parks Canada.

|

|

The Far North (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

|

The Chilkoot Trail (click on image for a PDF version) |

Setting

Hiking the Chilkoot Trail takes one through an ecologically varied and physically challenging terrain. The American side of the Trail follows the Taiya River within the confines of a narrow valley. Numerous glaciers, hanging like frozen waterfalls over the lip of the valley, are reminders that the Trail is surrounded by 1,500- and 2,500-meter peaks and miles of icefields. Most of the American side of the Trail is part of the Pacific Northwest coastal rain forest ecological zone. Sections of this part of the Trail flood rather easily after an abundant rainfall—which occurs often. As the Trail gains elevation and nears the Pass, it enters a mixed ecological zone of alpine meadow and tundra and of glacier and rock. In early summer, this area is blanketed by snow which melts steadily throughout the summer, leaving the area almost bare of snow by the end of summer. The Pass itself stands 1,082 meters above sea level. It is no place to linger when the weather is bad, which is generally the case. It is exposed to the full fury of southeasterly storms with their high wind, cold rain, and fog. If the weather is good, however, the panoramic vistas are superb.

The Canadian side of the Trail offers a dramatically different landscape. It is wide-open country highlighted by large alpine lakes, rushing streams, and rolling alpine meadows with clumps of dwarf conifers. The weather is more favorable (with less rain) on the Canadian side of the Trail, since the southeasterly storms tend to disperse as they blow-over the Pass. The mixed zone of alpine meadow and tundra and of glacier and rock continues as far as Deep Lake. In early summer, the Trail is covered by snow and the lakes are frozen. This snow lingers longer on the Canadian side of the Trail than on the American side. From Deep Lake to Bennett, the Trail enters a subalpine region and boreal forest as elevation diminishes. Wildlife can sometimes be found along the entire Trail, and the variety includes bear, mountain goat, wolverine, eagle, salmon, beaver, moose, loon, and other waterfowl.

There are five established camping areas on the Trail, each with outhouses and some with shelters: Canyon City, Sheep Camp, Happy Camp, Deep Lake, and Lindeman. The shelters at Canyon City and Sheep Camp are sturdy log structures with eight bunks and wood-burning stoves. At Lindeman, there are two rustic log cabins located on the lake shore and separated by a short walk. Each cabin has four bunks and a wood-burning stove. [8] During the stampede days, these three camping areas were bustling "tent cities" made-up of bars, restaurants, hotels, stores, repair shops, homes, and a sizeable transient population. The other two established camping areas, Happy Camp and Deep Lake, only have outhouses.

Relics of human-use are visible in their variety throughout the Trail. Historical relics (or garbage, depending on one's point of view) such as old shoes, rusty cans and utensils, bottleglass, and broken china await the discovery of the curious hiker. As the snow melts, especially in the vicinity of the Pass, remnants of the stampede emerge once again from their wintry tomb. The ruins of a tramway, old telegraph poles, and rotting sleds and boats all pay silent homage to the mass of humanity that trudged over the Chilkoot Pass during the days of the Klondike Gold Rush. Today, these artifacts are protected by law. Hikers are advised that it is illegal to remove or disturb any historical artifacts on the Trail. The ruins of Canyon City have been made accessible by a suspension bridge, providing hikers with a short side-trail. Among the more interesting remains is a rusty boiler used to power the most expensive and important of the four Chilkoot tramways. At Lindeman, a cemetery with 11 graves, called Boothill, has been restored and can be easily reached from the Trail. Other remains of human history are an old sawmill and logging road from the logging days of the early 1900's. These are located on the Trail between Dyea and Canyon City. A more recent addition to the collection are the remains of a small airplane which crashed into the American side of the Pass. Formal interpretation of the Trail is by means of metallic signs which include photographs of Gold Rush scenes with brief texts written both in English and French. These signs mark the trailheads, important sites, and certain events along the Trail.

|

| Chilkoot Pass, Winter 1898. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

chilkoot-trail-hikers/intro.htm

Last Updated: 27-May-2011