|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hikers on the Chilkoot Trail: A Descriptive Report |

|

METHODLOOGY

The field stage of the study of hikers on the Chilkoot Trail was undertaken by two, full-time field workers. [9] They were stationed with the Parks Canada patrolmen at Lindeman (on the Trail) from June 12 through September 14, 1976 Since the objective was to contact all hikers during the study period, both field workers alternated duty time, thus ensuring that the Trail was covered at all times. On occasions, Parks Canada patrolmen assisted the field workers in contacting hikers at Lindeman. The vast majority of hikers were met at Lindeman which is located 11 kilometers from Bennett, one of the Trail's two trailheads. Other contacts were made at Bennett while waiting for the train, at various points along the Canadian side of the Trail mostly between Bennett and Lindeman, and at Sheep Camp. The National Park Service rangers, stationed at Sheep Camp, made contact with all those people who were hiking solely on the American side of the Trail and who made it at least as far as Sheep Camp. When contacting hikers, the field workers made an effort to be as unobtrusive as possible, yet fulfill their research responsibilities. They were sensitive to the privacy of each hiker, prolonging the visit only when the hikers encouraged such behavior. Most of the hikers were met toward the end of their hike (85 percent of the hikers traveled from Dyea to Bennett).

The field workers (and the study) were well-received by the hikers. On numerous occasions, the field workers spent their evenings in a cabin or around a campfire talking with hikers on matters unrelated to the study. The field workers were particularly helpful in providing hikers with information about the Trail and the train. There were no incidents of refusal to cooperate on the part of the hikers. Hikers' reception ranged from excited cooperation to indifference. The positive reception of the study by the vast majority of hikers is further indicated by a 92 percent response rate, and by the request of 67 percent of the respondents for a summary of the findings, In response to the question, "do you approve of the research efforts undertaken this summer on the Chilkoot Trail?," 93 percent of the respondents (N = 1,352) answered affirmatively, while two percent responded negatively, and five percent did not respond. Those hikers who took advantage of the space allotted for comments regarding this research effort provided a variety of answers. Most of them affirmed their support for the study with such comments as "good idea," "good luck," "very interesting," "well-done questionnaire," "professional." The field workers received accolades—"persistent," "informative," "congenial," "hardworking"—from 44 of the respondents. Other respondents hoped the study's results would support their viewpoints (usually "no development" or "leave it as is"); or they supported similar efforts in other recreation areas; or they hoped the results of the study would be used by the Trail's managers. Most of the critical comments centered on the questionnaire itself: the wording or format or relevance of certain questions. The few who expressed disdain for the study felt that "forms are an intrusion in the woods;" or they disliked "degree-seeking, personal upgrading" researchers; or that "research money should be used for restoration."

The production of data on Chilkoot Trail hikers was based on the multi-method approach (Webb, et. al., 1966). This approach posits that a research project should use various research methods, each having different methodological weaknesses, in order to overcome the bias of any one method. Three distinct data-production methods were used: 1) a structured interview; 2) a mail questionnaire; and 3) participant observation.

Structured interview

The unit of observation for this method was the hiking party. [10] Each party was contacted separately. Members of each party were asked to provide certain information regarding their personal characteristics (e.g., age, sex, residence, whether they had hiked the Trail before) as well as their party's characteristics (e.g., type and size). This information was recorded on the Chilkoot party form (see Appendix 1). The name and mailing address of each hiker given a questionnaire was also written on the party form. Each hiking party was given a distinct number (beginning with #1) allowing for the identification of party members during the analysis of the data. The section for comments on the party form was used to note certain observations such as party formation, relationship among party members, the history of the party, and the presence of a dog. The Chilkoot party form was such that in many cases the hiking parties were able to fill-out the form without the assistance of or with minimal help from the field worker. In these instances, this method was more like an on-site questionnaire.

Mail questionnaire

Most of the Chilkoot data were produced using a mail questionnaire. The questionnaire was presented in the form of an attractive green booklet (see Appendix 2). Each questionnaire had a distinct number (beginning with #1). This questionnaire number was recorded on the party form for the appropriate hiker. In this way, each questionnaire corresponded to a particular hiker, along with his or her mailing address and personal data provided by the party form. In order to prevent party members from filling out the "wrong" questionnaire (i.e., filling-out a questionnaire whose number did not correspond to the questionnaire number recorded on the party form for the hiker in question), the first name of the particular hiker was written on his or her questionnaire. Hikers were also given a stamped and addressed envelope in which to return their completed questionnaire.

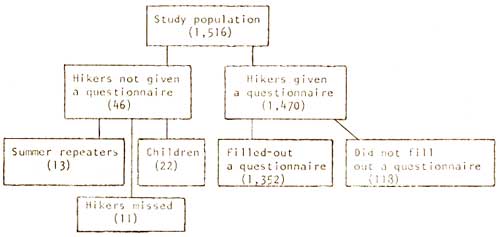

Our records show that during the study period of June 12 through September 14, 1976, 1,516 hikers hiked the entire Chilkoot Trail or portions of it. These hikers were organized into 484 hiking parties. The figure of 1,516 compares favorably with the 1,508 hikers reported by the National Park Service rangers. [11] We feel confident that the study population of 1,516 represents the universe of hikers during the study period. This study population represents 1,503 different persons. Our records show that 11 persons hiked the Trail on two separate occasions, while one person hiked the Trail three separate times. Data based on the Chilkoot party form were obtained from all 484 hiking parties and their members. Our strategy was to give questionnaires to all hikers, regardless of age. We distributed questionnaires to 1,470 hikers (97 percent of the study population). Those not given questionnaires were the following:

1. The 13 hikers who were summer repeaters (i.e., on their second or third separate hiking trip) were not given questionnaires. These persons were given a questionnaire on their first Chilkoot hike.

2. We were unable to contact 11 hikers which meant we could not give them questionnaires (i.e., we missed them). We were able, however, to acquire certain information from the National Park Service rangers and from other hikers which was sufficient to fill-out the party form, except for mailing addresses.

3. We did not give questionnaires to 22 hikers because of their young age (average age of 9.8 years). These children were not interested in filling-out a questionnaire, so we complied with their wishes.

Completed questionnaires were returned by 1,352 hikers, for a 92 percent response rate. These respondents represent 89 percent of the study population. We found that most of the non-respondents were youngsters, between the ages of four and 17.

A questionnaire intake and follow-up procedure was set-up at the College of Forest Resources, University of Washington, to monitor the return of completed questionnaires (Dillman, et. al., 1974). [12] One and then two reminders (letter, questionnaire, envelope) were sent out to those hikers who had not yet returned their questionnaire. The last completed questionnaire was received on February 18, 1977. As indicated in Table 1, 32 percent of the completed questionnaires were (most likely) the result of the system of reminders. Clearly, collecting mailing addresses and instituting a procedure for reminders make for a good response rate.

Figure 1

Statistical Breakdown of the Study Population

| Table 1. When the completed questionnaires were returned (N = 1,352). | ||

| When returned | Percentage | |

| Returned on the Trail | 10% | |

| Returned in the mail | 90% | |

| No reminders | 58% | |

| One reminder | 21% | |

| Two reminders | 11% | |

Participant observation

Participant observation is a multi-faceted research method which consists of observing human behavior and talking with people (Campbell, 1970). The field workers were involved in participant observation in two ways. First, by living on the Trail for the entire summer, they gathered information of a general nature about the hikers. They frequently hiked either portions of the Trail or the entire Trail. In a sense, they were hikers. They were part of the hiking scene on the Trail, occupying space on the Trail and interacting with other hikers. These interactions occurred at various places: in the shelters, on the Trail, at a campsite, at the warden and ranger camps, at Bennett, on the train, on the ferry, or in Skagway. Important insights were obtained from observations and conversations resulting from these encounters. These insights were recorded in a field journal. Second, the field workers were involved in the systematic observation of the places hiking parties chose to camp at Lindeman. In this case, the field workers focused on a single behavioral phenomenon to the exclusion of other events.

During the fall of 1976, the study's data were coded and then keypunched. A SPSS computer program was prepared for the Chilkoot data. The data cards with their SPSS computer program have been recorded on two separate magnetic tapes, one for safe-keeping and the other for use. A code book has been prepared which enumerates 166 variables, the value codes for each variable, and the frequency and percentage breakdowns for each variable (Field, et. al., 1977). It also provides information as to the coding strategy for certain variables.

The questionnaire provided hikers with space for writing comments, suggestions, and/or criticisms. The last two questions asked for comments about the research effort and any additional thoughts about the Chilkoot Trail and the hiking experience. In addition, several questions included space for explanations of answers. Respondents also utilized the large margins throughout the questionnaire to indicate their ideas (see Appendix 2). Using one coder [13] (which improves reliability), comments were read, categorized, and summarized for all 1,352 questionnaires. The vast majority of respondents (80 percent) used the opportunity to comment, suggest, and/or criticize. Often those not commenting were foreigners and younger respondents. Of those that provided comments (N = 1,085), 68 percent wrote their ideas throughout the questionnaire, while 23 percent used all segments of the questionnaire except for the final open-ended question, and nine percent responded only to the last page. In some cases, respondents got carried away by the blank space provided them at the end of the questionnaire, writing three pages of detailed comments and sometimes continuing on additional paper. This detail included drawings of improved bridge construction for the Trail, lists of nutritional food for backpackers, and ways to improve relations with the local citizenry (see Appendix 3 and Appendix 4). It should be noted that the comments were voluntary, so we were only able to read and record the ideas of those who had bothered to write them down. For this reason, the representativeness of these comments is questionable, for certain people tend to be more vocal or outspoken than others. Even so, these comments bear a wealth of information needing to be acknowledged. The synthesis and analysis of respondents' comments were not meant to be used as an opinion poll. Rather, the intent was to present the variety and frequency of specific details and ideas as well as to shed light on how the respondents interpreted and thus answered the questions. In other words this effort was used to clarify and highlight the statistical results of this study. Finally, many hikers saw the researchers as a link between them and the Trail's managers. They felt that the questionnaire was a medium for public involvement on issues regarding future management of the Trail.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

chilkoot-trail-hikers/methodology.htm

Last Updated: 27-May-2011