|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hikers on the Chilkoot Trail: A Descriptive Report |

|

A DESCRIPTIVE OVERVIEW

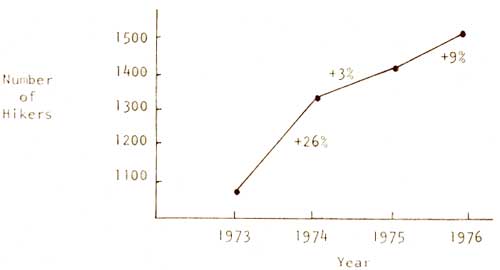

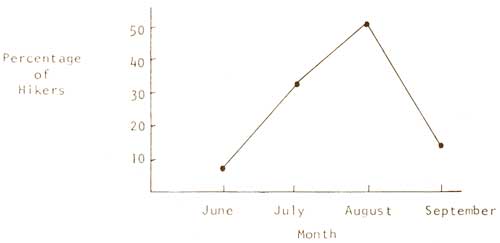

Over 30,000 stampeders trudged over the Chilkoot Pass during the Klondike Gold Rush era at the turn of the century. Since 1973, over 1,000 "modern stampeders" have traveled the Chilkoot route each year during the summer months. And each summer, the total number of hikers has steadily increased. Hikers visit the Chilkoot Trail during all four seasons. However, a review of the guest books at Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and Lindeman indicates that hiking activity begins to pick-up in mid-May, reaches its height in August, and diminishes by early October. Winter travel on the Trail is limited to a few hardy souls.

The purpose of this part is to present a descriptive overview of the Chilkoot hikers and their use-patterns. It consists of descriptive data (mostly percentages) and a summary of respondents' comments. Three distinct population figures are used:

1) the study population of 1,516 hikers;

2) the study population of 4 hiking parties; and

3) the study population of 1,352 questionnaire respondents.

Figure 2. Number of hikers on the Chilkoot Trail

during the summer beginning in 1973) and the percentage

increase. [14]

Figure 3. Percentage of hikers during each summer

month of 1976 (N = 1,516). [15]

This descriptive overview has been organized into five sections to facilitate reading. First, we describe the population of Chilkoot hikers using the traditional socio-demographic variables. In addition, we suggest another way to describe and differentiate a population of hikers using several variables measuring "hiking experience." Second, there is a discussion of the preparation for the hike, focusing on sources of information, knowledge of Gold Rush history, and motivations for hiking the Trail. This then takes the reader to the hike itself. At this point, we describe the use-patterns on the Trail as well as the social organization of hikers. This latter topic carries-over to the fourth section which considers travels in the Far North. And finally, there is a discussion of respondents' evaluations of the conditions and facilities of the Trail and hikers' opinions on management options for the Trail.

Section 1: Who the hikers are.

Socio-demographic characteristics have been used in recreation research as variables to identify trends in the user population being studied. Specifically, data from these variables facilitate comparisons with similar data from the larger population (e.g., U.S. population) or from other study populations (Burch and Wenger, 1967). These variables have also provided researchers with explanations for certain aspects of human behavior. For example, Burch (1966) has shown how social age influences a person's choice of camping style. Bultena and Field (1977) found that income, education, occupation, and a cumulative status index, were positively related to rates of national park-going, although these "class differences among visitors were not sufficient to warrant a conclusion of 'elitism' in national park use." Vaux (1975), similarly, concluded that persons with high incomes represent a disproportionately large group of wilderness users in California. For the Chilkoot study, we focused on five of these characteristics: age, sex, education, occupation, and residence. A comparison of the Chilkoot socio-demographic characteristics with those of other backcountry (wilderness) studies suggests similarity in the general findings. [16] Differences in terms of actual percentages were found between the Chilkoot study and other such studies for two characteristics: sex and residence. These will be discussed in this section at the appropriate place.

Age. The ages of the study population ranged from four to 73 with the average being 27 years of age. The youngest was a girl who hiked the entire Trail with her six year old sister and their parents. The oldest hiker was the wife of a Gold Rush stampeder who hiked the entire Trail with her grandson and friends. A breakdown of the study population by "social age" indicates that close to half of the hikers were adults followed by young adults and juveniles. [17]

| Table 2. Social age of hikers (N = 1,516). | |

| Social age | Percentage |

| Infant (<7) | 00.2% |

| Juvenile (7-17) | 19.7% |

| Young adult (18-24) | 25.8% |

| Adult (25-49) | 47.4% |

| Older Adult (>49) | 06.7% |

| No information | 00.3% |

| Mean: 27.3 Standard deviation:11.5 | |

Sex. There were more male hikers on the Trail (60 percent) than female hikers (40 percent). Last summer's sex ratio differs dramatically with that during the Gold Rush days when females comprised a very small number of the population of stampeders. [18]

Education. Close to 30 percent of the questionnaire respondents were students at various levels of school. One hiking party of 22 included 17 Alaskan "bush kids" on a special trip as part of their correspondence school. Of those who were no longer in school, the vast majority had completed at least some college. Furthermore, for many hikers, the Chilkoot hike was an educational experience.

| Table 3. Highest educational level attended by hikers who were no longer in school (N = 951). | |

| Educational level | Percentage |

| Elementary (1-8) | 01.5% |

| High school (9-12) | 16.9% |

| College (13-16) | 45.1% |

| Post College (17+) | 34.3% |

| No information | 02.2% |

Occupation. As in the Gold Rush days, Chilkoot hikers came from all walks of life. There were Yukon miners on strike and soldiers on a military maneuver. One hiking party was comprised of medical doctors and their families from a central California town, while another consisted of seasonal foresters at the end of their summer stay in Alaska. Some hikers had come to the Far North hoping to find employment. Except for the large number of students, most of the respondents were part of the labor force. Of those inside the labor force, a large majority mentioned "white collar" occupations with professional and technical jobs as the most representative. When considering the specific occupations of the hikers, the teaching profession (elementary, high school, and university) was, by far, the most common one (N = 172). It was followed by the health profession (doctors, nurses, therapists, and technicians) with 87. [21]

| Table 4. Hikers inside and outside the labor force (N = 1,352). | |

| Labor force status | Percentage |

| Inside the labor force | 62.8% |

| Outside the labor force [19] | 30.8 |

| No information | 06.4 |

| Table 5. Occupations of those inside the labor force (N = 850). | ||

| Occupation Category [20] | Percentage | |

| White collar occupations | 72.8% | |

| Professional and technical | 57.6% | |

| Manager and administrator | 07.4% | |

| Sales | 02.4% | |

| Clerical | 05.4% | |

| Blue collar occupations | 14.8% | |

| Craftsman | 05.6% | |

| Operators | 03.4% | |

| Laborers | 02.5% | |

| Farmers | 00.5% | |

| Service | 02.8% | |

| Other | 12.4% | |

| Homemaker | 04.9% | |

| Military | 02.4% | |

| Unemployed | 05.1% | |

Residence. [22] Chilkoot hikers, as in the stampede era (about four-fifths of the stampeders were Americans), came from all over the world, although most were from the United States and Canada. One West German hiker had read a magazine article on the Chilkoot Trail while traveling in Africa. There was an English family who sailed their boat (which was also their home) from Hawaii to Skagway and were on their way to British Columbia to establish a new residence. Although American hikers outnumbered Canadian hikers by a margin of two to one, this difference is not so significant if one considers that the U.S. population is nine times as large as that of Canada. The American hikers originated from 40 states (including the District of Columbia), with Alaska having the highest representation. The Canadian hikers came from ten provinces and territories, with Yukon Territory and then British Columbia having the largest percentages. Finally, ten foreign countries were represented on the Trail last summer with West Germany serving as the residence for the majority (66.7 per cent) of the foreign hikers (N = 57). [24] Apparently, Gold Rush history was given a lot of publicity in West Germany during the months prior to the summer of 1976. Even though hikers came from all over the world, close to 40 percent of them were area residents of Alaska and Yukon Territory. [25] If residents of Washington and British Columbia are added on as area residents, then the percentage increases to 55 percent. [26]

| Table 6. Residence of hikers, by country (N = 1,516). | |

| Country | Percentage |

| United States | 62.6% |

| Canada | 33.6% |

| Foreign countries | 03.8% |

| Table 7. Residence of American hikers (N = 949). | |

| States [23] | Percentage |

| Alaska | 43.2% |

| Washington | 10.4% |

| California | 19.2% |

| Other western states | 08.3% |

| Midwestern states | 12.0% |

| Southeastern states | 02.1% |

| Northeastern states | 04.8% |

| Table 8. Residence of Canadian hikers (N = 509). | |

| Province or territory | Percentage |

| Yukon Territory | 36.0% |

| British Columbia | 26.2% |

| Alberta | 18.8% |

| Saskatchewan | 00.8% |

| Manitoba | 01.6% |

| Northwest Territory | 01.0% |

| Ontario | 13.0% |

| Quebec | 02.0% |

| New Brunswick | 00.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 00.4% |

In addition to these socio-demographic characteristics, we have included another way to describe and differentiate a population of hikers: by their "hiking experience." This variable measures a person's background as a hiker. Consequently, there are numerous indicators of this variable (e.g., frequency of hiking trips, nature of these trips, age of first hike). As a descriptive measure, this variable provides useful information as to the level of hiking experience a person brings to a backcountry area. Such information, for example, is of value to management in the area of user safety. Similarly, as an analytic variable with behavioral dimensions, hiking experience might assist researchers in understanding some of the differences in hikers' attitudes and use-patterns.

During the summer of 1976, hikers arrived on the Chilkoot Trail with a wide range of hiking experiences: from the novice on his or her first overnight hike, to the expert with many years of hiking and mountaineering adventures. As documented in numerous journals and diaries written by the cheechakos, the trek over the Chilkoot Pass during the gold rush was often a treacherous undertaking. Even today, the Trail continues to be a challenge which taxes even the more experienced hikers. During the days of the Klondike stampede, most of those traveling the Trail were newcomers to such a wilderness setting and its resulting hardships. Last summer, at least about ten percent of the hikers were getting their first tastes of overnight hiking. And close to 93 percent of the hikers were visiting the Trail for the first time. [27] Comparing the Chilkoot hike with previous backcountry treks in terms of miles-traveled and days-out, the Chilkoot hike offered a new backpacking experience for 63 percent of the hikers. By combining the results from four variables, we have constructed an index of hiking experience with possible scores ranging from four to 20 (see Appendix 4). Table 10 emphasizes the point that Chilkoot hikers came to the Trail with a wide range of hiking backgrounds.

| Table 9. Comparison of the Chilkoot hike with previous backcountry hikes (N = 1,352). | |

| Prior to the Chilkoot hike, had you been on a hike longer than the Chilkoot hike in terms of miles-traveled and days-out? | Percentage |

| Had not been on a longer hike both in term of miles-traveled and days-out. | 45.9% |

| Had been on a longer hike in terms of miles-traveled but not in terms of days-out. | 05.7% |

| Had been on a longer hike in terms of days-out but not in terms of miles-traveled. | 11.8% |

| Had been on a longer hike both in terms of miles-traveled and days-out. | 35.4% |

| No information | 01.2% |

| Table 10. Index of hiking experience (N = 1,352). | |

| Level of hiking experience | Percentage |

| Beginner (4-9) | 29.8% |

| Intermediate (10-14) | 40.2% |

| Advanced (15-20) | 28.4% |

| Insufficient information | 01.6% |

| Mean: 11.6 Standard deviation: 4.0 | |

Given this range of hiking experiences and the surprising number of newcomers to backpacking (many of whom did not appear to be "adequately" or "properly" equipped for the occasion), one might expect a certain number of accidents on as rugged a trail as the Chilkoot. Surprisingly, there were no major accidents on the Trail during the summer of 1976. One young girl severely sprained an ankle and required assistance from a helicopter. A few others sustained some minor cuts, bruises, and breaks. For some hikers, the Chilkoot hike was an unpleasant occasion because of inexperience or inadequate equipment or poor preparation. A review of the reports by the National Park Service rangers and Parks Canada patrolmen from previous summers confirms this observation. This phenomenon might be a testament to the preparedness of the hikers (or to the superfluous concern with equipment, especially the "latest") and to their fortitude and determination, as well as to the fact that rangers and wardens patrolled the trail daily. Furthermore, other hikers on the Trail came to the aid of those hikers in potential or real trouble. [28]

Section 2: Preparing for the hike.

For some, hiking the Chilkoot Trail was the culmination of years of dreaming and planning. For others, the decision to hike the Trail was spontaneous, made within a few days of actually setting-out on the hike. While 43 percent of the Chilkoot hikers had considered the trip for six months or more, approximately 32 percent of them decided to make the hike within a month of the hike and almost to half of these decided within a week. These decisions were often made just before leaving home or while in transit. They had heard about the Trail while on the ferry heading north to Alaska, traveling the Alcan Highway, on the train between Skagway and Whitehorse, or while visiting towns in the vicinity of the Trail.

| Table 11. When did you first consider hiking the Chilkoot Trail? (N = 1,352). | |

| Time period | Percentage |

| Within one week | 14.9% |

| Within one month, but more than one week | 17.3% |

| Within six months, but more than one month | 24.2% |

| Within one year, but more than six months | 14.8% |

| Over one year | 28.1% |

| No information | 00.7% |

Hikers identified various sources of information used to find-out about the Trail. Although they were allowed to check more than one source, over three-quarters indicated only one. By far the most important source of information was "word of mouth"—far outdistancing printed material. Previous Chilkoot hikers, including old-timers and relatives who crossed the Pass in 1898, were mentioned by several hikers indicating family and friends as a source of information. Pierre Berton's works, especially Klondike and The Klondike Fever were cited by one-third of those who used historical publications as an informational source, with an almost equal number mentioning Archie Satterfield's Chilkoot Pass: Then and Now. Jack London and Robert Service were popular fiction authors among hikers. Over one-third of those citing newspapers and magazines mentioned Alaska magazine and its publication Milepost. National Geographic and several British Columbia journals were also frequently mentioned. Leaders of organized hiking parties such as the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts were often mentioned as informational sources. Likewise, leaders of Klondike Safaris (a private hiking guide service), the Sierra Club, and the Mazamas were also indicated as sources. The category, "general knowledge," includes those respondents who learned about the Trail from living in the area or from attending school in the area. Margaret Piggott's Discover Southeast Alaska with Pack and Paddle was cited by nearly half of those who checked hiking guides. The old version of the Trail guide was mentioned more often than the new guide, although users of the new guide may have checked Parks Canada and National Park Service information. [30] The movie, City of Gold, whether seen in Dawson or on the ferry, was the most mentioned in the category, "T.V., radio, or movies," followed by Call of the Wild which had been seen by many of the West Germans. About one-quarter of those indicating travel brochures or books specified Lou Jacobin's Guide to Alaska. The Yukon tourist information bureau also provided many brochures. Finally, some hikers mentioned that they had learned about the Trail from previous travels, especially on the White Pass and Yukon Railway.

Many of the sources of information about hiking the Chilkoot Trail were also used to learn about Gold Rush history (see Appendix 5). Over 85 percent of the hikers were familiar with Gold Rush history prior to their hike, although we do not know to what degree. More than three-quarters of those knowledgeable about the history of the Klondike stampede cited one (40 percent) or two (37.6 percent) sources of historical information. Printed materials were listed most often. An assortment of historical books was read by hikers with Pierre Berton and Archie Satterfield as the authors whose works were read most often. Some other books mentioned were: Jack London's Call of the Wild; Morgan's book on Hegg and his photographs, One Man's Gold Rush; Robert Service's poems; Martinsen's Black Sand and Gold; and Laura Berton's I Married the Klondike. The old and new Trail guides were mentioned by some hikers as sources of historical information. Old timers, including relatives who traveled the Chilkoot Trail during the Gold Rush stampede, provided stories about the Gold Rush of '98 to their younger friends and family members. Other hikers learned some history while traveling in the area. The museums in Skagway, Whitehorse, and Dawson were visited by some before hiking the Chilkoot Trail. [32]

| Table 12. How did you learn about the Chilkoot Trail? (N = 1,352). | |

| Sources of information | Percentage |

| Family and friends | 59.5% |

| Historical publications | 16.1% |

| Newspapers and magazines | 09.9% |

| Casual acquaintance on ferry, in Skagway, or in Whitehorse | 08.6% |

| Party leader or organizer | 08.1% |

| General knowledge | 07.8% |

| Hiking guides | 05.0% |

| Parks Canada and National Park Service information | 05.0% |

| T.V., radio, or movies | 04.2% |

| Travel brochures or book | 03.8% |

| Travel experience | 02.4% |

| Other [29] | 01.0% |

| No information | 01.3% |

Even with all this emphasis on the Trail's historical role, its history was not the only, nor the primary attraction to hikers. In response to an open-ended question as to why people hiked the Trail, many reasons were provided (see Appendix 6). Most of the answers, however, dealt with hiking opportunities or the historical resource. Close to 48 percent of the respondents provided answers which fell into one category, while 46 percent wrote 2-category answers. Those answers which mentioned such things as exercise, scenery, physical challenge, nature, or "to get away" were categorized as "hiking," while those indicating a desire to see or experience Gold Rush history were coded as "history." An expressed desire to be hiking in the company of family members or friends was coded as "social." Some people were encouraged to hike the Trail by friends or relatives, many of whom had done it themselves. In some cases, people had to hike the Trail as a "social responsibility." This was especially true for some children whose parents wanted to go and for some wives whose husbands had expressed a wish to hike the Trail. There were a few persons for whom hiking the Trail was a job. They were members of organized hiking parties (e.g., Klondike Safaris, Scouts) The convenience of the Trail (primarily its easy access) beckoned some persons who happened to be in the vicinity and had some spare time. Similarly, others used the Trail as a transportation corridor in order to save money which would have gone for train fare. There were certain people who hiked the Trail because it fit into their travel itinerary in the Far North. Questionnaire answers categorized as "other" are varied in their content. They include: "on strike;" "military maneuver;" "for a merit badge; " "to ride the narrow gauge train;" "for the meal at Bennett;" "for the experience;" "because it was interesting;" 'why not?;" "something to do;" "I wanted to wear leather boots for a change;" "beats me;" and "do I have to have one!".

| Table 13. How did you learn about Klondike Gold Rush history? (N = 1,152). | |

| Source of historical information | Percentage |

| Books | 66.8% |

| Magazines, pamphlets, or newspapers | 31.3% |

| Family and friends | 23.1% |

| School | 15.7% |

| Living in the area | 10.2% |

| Movies, T.V., or radio | 10.2% |

| Museum | 06.4% |

| Travel experience | 05.9% |

| Library | 04.7% |

| Other [31] | 02.5% |

| No information | 01.7% |

The motives for hiking the Chilkoot Trail are undoubtedly much more complex than is suggested in Table 14. What is instructive about the responses to this question is that hiking reasons are as important (if not more so) as historical reasons. Close to 77 percent of the respondents expressed motives involving hiking and/or history. Of these (N = 1,037), 47 percent mentioned both hiking and history as reasons for coming to the Trail while 32 percent mentioned only hiking, and 21 percent mentioned only history. Clearly, the Chilkoot Trail is as much a backcountry resource in the eyes of the hikers as it is an historical resource. [33] The observation of a dual definition of the Trail is reinforced by the results in Table 15. It is possible that hikers arrived at the Trail with a set of expectations (see Table 14), and yet left the Trail realizing more ways to define this area (see Table 15). For example, history buffs frequently expressed surprise at the natural beauty of the area, while avid backpackers were impressed by the existing relics and the presence of the interpretive signs. Furthermore, beside the percentages in Table 14, answers to the open-ended question as to why people hiked the Trail are of interest because they suggest a variety of reasons why people might hike the Chilkoot Trail (see Appendix 6).

| Table 14. Why did you hike the Chilkoot Trail? (N = 1,352). | |

| Reasons | Percentage |

| Hiking | 60.4% |

| History | 52.2% |

| Social | 07.7% |

| Fun, pleasure, and enjoyment | 04.7% |

| Encouraged by a friend or relative | 04.4% |

| Social responsibility | 04.0% |

| Job responsibility | 02.9% |

| Convenience of the Trail | 01.9% |

| Transportation trail | 01.8% |

| Live in the area | 01.8% |

| Part of the travel itinerary | 01.1% |

| Other | 08.1% |

| No information | 02.3% |

| Table 15. How would you describe the Chilkoot Trail? (N = 1,352). | |

| Description [34] | Percentage |

| Both an historical and backcountry trail | 83.2% |

| An historical trail | 15.2% |

| A backcountry trail | 00.9% |

| No information | 00.7% |

Section 3: Hiking the Chilkoot Trail. [35]

The flow of hikers on the Chilkoot Trail moved primarily in a northerly direction: from Dyea to Bennett. Many travelers commented that this was "the historical way." As one hiker who had begun the hike at Dyea exclaimed, referring to a party she had encountered traveling in the opposite direction: "I sure didn't come all the way from Arizona to hike the Trail backwards!". In fact, however, some stampeders returned to Alaska from the Klondike gold fields by way of the Chilkoot Pass. Five hikers began their trek in the White Pass area. They traveled cross-country, picking-up the Trail on the Canadian side of the Pass.

Most visitors hiked the entire Trail, in one direction, although a few traveled in both directions. Of those who hiked only part of the Trail, a little less than half of them hiked the American side of the Trail, reaching the Pass and then turning around. The others visited the Canadian side of the Trail, some either hiking to the Pass and returning to Bennett or traveling only as far as Lindeman or Deep Lake, satisfied to enjoy the scenery and the comfort of the cabins.

| Table 16. Direction of travel on the Trail (N = 1,516). | |

| Direction of travel | Percentage |

| Dyea to Bennett | 85.8% |

| Bennett to Dyea | 11.2% |

| No information | 03.0% |

Hiking the Chilkoot Trail may be viewed as a process, with a beginning and an end with a series of changes in-between. For most parties this process lasted for three, four, or five days. The first part of the trip was a preparation for actually climbing the Pass. Once having attained the summit, a feeling of exhilaration and exhaustion settled-in. It was a time, depending on the weather, to commune with the ghosts of the stampeders and to savor the scenic vistas or to plod onwards in search of shelter. Upon reaching Lindeman, hikers began to feel good about the accomplishment of having surmounted the Pass and its elements. Their thoughts shifted to the next step: catching the train at Bennett; the return trip home; responsibilities at work; or the next stop on the travel itinerary. In fact, for many, the hike was essentially over at Lindeman. The trek from Lindeman to Bennett was anticlimatic, and the wait at Bennett was boring (fearful of missing the train many would arrive at Bennett hours before its arrival). But once the train rolled into the station and the passengers disembarked, the excitement of the Chilkoot hike resurfaced as the tourists from the train queried the hikers about their Chilkoot adventures.

| Table 17. Extent of the hike (N = 1,516). | |

| Extent of the hike | Percentage |

| Hiked the entire Trail, one way | 90.9% |

| Hiked the entire Trail, both ways | 01.3% |

| Hiked only part of the Trail | 05.1% |

| No information | 02.7% |

Time was an important consideration for many hikers. They were on tight schedules, which left little opportunity for exploring the Trail. They were intent on completing the hike as soon as possible in order to go on to other things. For some, it was a race against the clock. There were two people visiting the Trail for the third time who had shortened their hiking time with each trip. [36] Over half of those who had hiked the entire Trail did not visit both of the accessible ruins located just off the Trail: Canyon City ruins and Lindeman's Boothill (although 86 percent visited at least one of the two ruins). Furthermore, only 21 percent (N = 1,352) of the hikers engaged in off-Trail explorations (not including jaunts to Boothill and the Canyon City ruins), and the vast majority of these never exceeded a few hundred meters from the Trail. Most off-Trail visits occurred in the area of the Pass (N = 92), where the boats at the summit were a popular attraction. Some hikers ventured over to the plane crash. Most other off-Trail trips occurred in the vicinity of overnight camps, primarily Sheep Camp (N = 54) and Lindeman (N = 49). It may be that side trips were not a priority for most hikers. A four-day trip allows little time for exploration, especially for slower hikers. In fact, many people commented that they wished they had more time to explore the Trail; and some even talked about returning to the Trail, allowing for more time to enjoy the hike. Under certain conditions, the hiking event itself took precedence over visits to even the most significant historical sites. When it is cold, foggy, and raining, and there are 15 kilometers to go before shelter, hikers may not desire to stop and inspect the ruins of an old wagon.

| Table 18. Number of days hiking the Trail (N = 1,516). | |

| Number of days | Percentage |

| 1 | 00.4% |

| 2 | 03.9% |

| 3 | 25.1% |

| 4 | 35.2% |

| 5 | 26.5% |

| 6 - 15 | 05.7% |

| No information | 03.2% |

| Mean: 4.1 Standard deviation: 1.1 | |

| Table 19. Did you visit the Canyon City ruins and the cemetery at Lindeman? (N = 1,276). | |

| Percentage | |

| Visited both the Canyon City ruins and the cemetery at Lindeman | 45.4% |

| Only visited the Canyon City ruins | 20.4% |

| Only visited the cemetery at Lindeman | 20.1% |

| Did not visit either place | 13.7% |

| No information | 00.4% |

Although there were no regulations about where hikers had to camp, certain spots were popular. As might be expected, the established camping areas (especially those with shelters and outhouses), were used most often. These are Sheep Camp, Lindeman, Canyon City, Happy Camp (most of those camping between the Pass and Lindeman camped here), and Deep Lake. Over 60 percent of the hikers did not travel between Sheep Camp and Lindeman in one day (either by choice or necessity), requiring a stop-over along the Trail, mostly at Happy Camp or Deep Lake. Almost 30 percent of the hikers chose not to camp at Lindeman but rather to continue a bit further, in many cases to make the next day's hike to the train less frantic. Many of these people chose to camp at Bare Loon Lake or the smaller lake nearby. The majority of hikers who camped at Canyon City, Sheep Camp, or Lindeman, "used" the shelters. [38] Our observations of camping behavior at Lindeman indicated that hikers usually filled the cabins before beginning to occupy tent sites.

|

| Descending the Pass into Canada |

| Table 20. Where hikers camped on the Trail (N = 1,516). | |

| Camping area [37] | Percentage |

| Dyea | 02.4% |

| Sawmill | 08.8% |

| Between Dyea and Canyon City (not including the Sawmill) | 12.1% |

| Canyon City | 52.2% |

| Between Canyon City and Sheep Camp | 06.3% |

| Sheep Camp | 69.5% |

| Between Sheep Camp and Pass | 08.2% |

| Pass | 01.4% |

| Deep Lake | 18.4% |

| Between Pass and Lindeman (not including Deep Lake) | 43.2% |

| Lindeman | 55.5% |

| Between Lindeman and Bennett | 23.7% |

| Bennett | 06.0% |

| No information | 04.2% |

| Table 21. Use of the shelters by those camping in areas with shelters. | |

| Shelter area | Percentage of those using the shelters |

| Canyon City (N = 791) | 52.7% |

| Sheep Camp (N = 1,053) | 60.2% |

| Lindeman (N = 841) | 66.1% |

| Table 22. Size of hiking parties (N = 484). | |

| Party size | Percentage |

| 1 | 19.2% |

| 2 | 43.4% |

| 3 | 13.3% |

| 4 | 10.6% |

| 5 | 04.6% |

| 6 - 12 | 06.7% |

| 13 - 33 | 02.2% |

| Mean: 3.1 Standard deviation: 3.5 | |

Shelters functioned as the "social hub" for the Trail. Evenings at the shelters were settings for "social gatherings" (Goffman, 1963). On many occasions, the shelters were full of hikers, including those tenting nearby. While people were busy preparing food or drying-out or resting their weary bodies, the situation was conducive to friendly interaction between strangers: acquaintances were made; tales of former hiking adventures were told; information about the Trail and the history of the Gold Rush was exchanged. One might imagine that these social gatherings were in fact re-enactments of what transpired in the original human settlements of Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and Lindeman City during the days of the stampede.

Close to 94 percent of the hikers arrived on the Trail organized in groups of friends and family members. We identified 484 hiking parties, ranging in size from a single hiker to 33. [39] The ascertained average party size of three compares favorably with similar information from other National Parks in the Northwest. The Chilkoot hiking parties were categorized into five types:

1) Alone: hiker traveling by himself or herself;

2) Family: a hiking party comprised of relatives, all of whom are related as part of a single nuclear or extended family;

3) Friends: a hiking party comprised of friends, none of whom are relatives;

4) Family and friends: a hiking party comprised of friends, some of whom are relatives; and

5) Organized: a hiking party whose members were brought together by some organization such as a club, school, scout troop, or tour group.

Dogs accompanied 4.5 percent of these hiking parties with a total of 28 dogs traveling the Trail in the summer of 1976.

| Table 23. Type of hiking parties (N = 484). | |

| Party type | Percentage |

| Alone | 19.2% |

| Family | 23.2% |

| Friends | 38.8% |

| Family and friends | 13.6% |

| Organized [40] | 05.0% |

| No information | 00.2% |

The nature of the Chilkoot Trail was conducive to interaction among hikers: there is only one trail with shelters along the way, and most hikers traveled in the same direction (Dyea to Bennett) at roughly the same speed. As the hike progressed and as people began to make contact with each other (while hiking or while camping), two social phenomena became apparent. First, hiking parties were being formed. Either existing parties of two or more would coalesce to form one larger party; or a solitary hiker would join an existing party of two or more; or two or more solitary hikers would band together to form a party. Second, and more common, a feeling of camaraderie began to emerge among hikers (although they maintained the boundaries of their original parties). These phenomena of party formation and camaraderie have yet to be reported in the backcountry literature. Some recreation researchers, however, have emphasized the importance of focusing on the social organization of people in recreation settings (Cheek, et. al., 1976; Cheek and Burch, 1976). They argue that recreation behavior needs to be studied at the level of the social group (rather than at the level of the individual) since people recreate in the company and presence of other people.

Among Chilkoot hikers, party formation and camaraderie occurred even prior to their arrival at the Trail: on the ferry or train, in Skagway or Whitehorse, or on the road to the Far North. By the time hikers had arrived at Lindeman, new friendships had been developed. Messages and greetings were left behind for others who had not yet reached Lindeman. Hikers who had been strangers to each other just a day or two before made plans to continue together exploring the Far North.

|

| Deep Lake campsite |

Section 4: Traveling in the Far North.

The Chilkoot Trail hike was often part of a larger travel adventure in the Far North (Alaska and Yukon Territory). A troop of Boy Scouts from Illinois is a good example: they took the ferry from Seattle to Skagway; after the Chilkoot hike, they canoed from Whitehorse to Dawson; then they visited Mount McKinley National Park and the Fairbanks area; and finally, they flew to Barrow for a short visit. Over 60 percent of the hikers lived outside of Alaska and the Yukon, and almost 70 percent of them were visiting the Far North for the first time. Thirty-eight percent of these visitors to the Far North expressed that hiking the Chilkoot Trail was the primary purpose of their visit. For the majority (N = 525), however, there were other main reasons for the visit. Mostly they were: to explore the Far North (66 percent); to visit family and friends (13 percent); for business (13 percent); and to travel the Yukon waterway (9 percent). [41] In August 1976, a hiker from Wisconsin arrived at Lindeman from Dyea packing a kayak. He launched it at Lindeman in the direction of Dawson. Another hiker from New York canoed from Bennett to the Bering Sea via the Yukon River in 88 days. In the winter of 1897-98, Lindeman and Bennett were large settlements of stampeders building boats and waiting for the arrival of spring. These settlements represented the end of the hiking segment of the stampeders journey to the Klondike gold fields. On May 29, 1898, spring break-up came to Lake Bennett and some 800 boats embarked on their journey to Dawson City. Within 48 hours, the settlements were abandoned, and a flotilla of 7,124 assorted boats was in motion down Lakes Lindeman and Bennett.

Boating the Yukon waterway was just one of the many activities visitors to the Far North engaged-in before and after the Chilkoot hike. Some hikers arrived at the Trail having already visited other Alaskan or Yukon recreation places. Some had traveled by ferry through southeastern Alaska, visiting the towns in route. Trips to Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau and to nearby Glacier Bay National Monument were popular. Others had traveled the Alcan Highway, visiting the historic sites in Whitehorse and Dawson. For some, hiking the Trail was the first adventure of their trip, with other recreation experiences to follow. Some hikers continued on the Gold Rush route by train, and automobile or bus to Dawson. Others headed north to the wildlands of Kluane National Park (Yukon Territory), Mount McKinley National Park (Alaska), and Alaska's Kenai Peninsula (Chugach National Forest). These travel patterns are similar to those found in a study of visitors to National Parks in the state of Washington (Catton, 1966). [42]

| Table 24. For those not residing in Alaska or the Yukon, was this your first visit to the Far North? (N = 844). | |

| Percentage | |

| Yes | 68.4% |

| No | 31.2% |

| No information | 00.4% |

Section 5: The opinions of the hikers.

Hikers were asked to evaluate the existing condition of certain aspects of the Chilkoot Trail. They were provided with a range of possible answers:

Excellent (E)

Above average (AA)

Average (A)

Below average (BA)

Inferior (I)

as well as with space to write their comments. [43] Overall, hikers were pleased with the conditions and facilities of the Trail. Most of the evaluations given were "average" or better, with the mean answer being "above average."

| Table 25. How would you evaluate the preservation of historical relics and landmarks on the Trail? (N = 1,352). | |||||

| E | AA | A | BA | I | No information |

| 19.8% | 29.3% | 29.2% | 12.3% | 04.7% | 04.7% |

Half of the hikers felt that the preservation of landmarks and relics on the Trail was "above average." There was a tendency among those hikers who commented to mention the following reasons for such high evaluations: "the relics appear untampered;" "many remain too heavy to carry-out;" "there was an amazing number of them left to see;" "they were well preserved especially considering the conditions," "natural decay was the best treatment since museums and glass cases would be out of place;" "they were impressive left on the trail for hikers 'to discover'"; "they added to the experience and flavor of the hike by lying as left in 1898;" and ""they were OK now but there may be a problem in the future."

Among those who commented after rating the preservation as "below average" or "inferior," the major complaint was that the artifacts have been, are being, and will continue to be tampered with, removed, or weathered. These hikers wanted "to see some preservation" and "more done about restoration at a few sites." They saw a "need to catalogue and identify the artifacts," and they feared that there "won't be any left for the future." Others merely commented "what preservation?" or stated that "nothing's being done."

The rest of the comments, especially those made by hikers who rated the preservation as "average," centered around not being sure how to answer the question. At best 114 respondents felt that it was hard to judge because they had no basis for comparison; they did not know what preservation meant; or they could not locate and identify the ruins which were often snow-covered or overgrown by brush. Many of these people felt it was impossible to preserve relics, while others saw hope in the establishment of the new park. Over 70 hikers commented that they had expected to see more relics, especially at the Canyon City ruins, and that they "felt let down." For over 30 hikers, the artifacts were no more than piles of old garbage.

| Table 26. How would you evaluate the historical interpretive signs in terms of their success interpreting the Trail's history? (N = 1,352). | |||||

| E | AA | A | BA | I | No information |

| 49.6% | 32.1% | 13.8% | 02.0% | 00.3% | 02.1% |

The historical interpretive signs were overwhelmingly praised. More than 300 respondents added extra praise to their high ratings of these signs, calling them "meaningful," "informative," "enjoyable," "a great excuse for a rest stop," "sensitive," "exciting," "a great addition," and "enhancing." Over 100 respondents applauded the photographs, often describing them as an "effective way to relate past to present." Another 22 hikers liked these photos but felt that several were "mislocated" or "confusing when not oriented to the same point."

More signs, especially at "significant points of interest," were requested by 132 hikers. Fifty-three indicated that no more signs should be added since "the present number and placement are appropriate" and that "more would be obtrusive." While still rating these signs as "average" to "excellent" in effectiveness, 42 respondents found them "distasteful," "unaesthetic," and "too conspicuous." While several of these hikers suggested removing the signs, more asked for a pamphlet or guidebook instead.

About 80 hikers described the text of the signs as "brief." While half of these desired more information, the others felt that brevity was acceptable, since hikers could get the "complete story" from other sources. Over 30 people had trouble reading the signs due to water condensation under the plexiglass, sun glare, or hard to reach locations of signs. Several less frequent criticisms involved "inaccurate," "repetitious," "racist," or "sexist" texts.

Turning now to the evaluations of the physical condition of the Trail, many of the comments indicated that the respondents considered the difficulty and scenic attractions of the Trail in their evaluations. When commenting on the Trail as a whole, 265 hikers felt it was "just as it should be" or "acceptable." These people indicated that it was rugged, but that this was an "important part of the experience" and a "challenge." They found it: "well-marked;" "as good as expected considering the terrain;" and "not in need of any but minor improvements." Forty hikers actually found the Trail toers were a controversial issue: 125 respondents recommended them for the Canadian side, and 29 sought their removal on the American side. Many of those who wanted mile markers, however, felt that it was not necessary to have them every one-half mile but perhaps only every two or three miles. Mile markers were especially desired by hikers who were concerned about reaching shelter or who feared missing the train at Bennett because they could not tell how far they had left to go.

| Table 27. How would you rate the physical condition of the Trail? (N = 1,352) | ||||||

| Evaluation | ||||||

| Section of the Trail | E | AA | A | BA | I | No information |

| Between Dyea and Canyon City | 26.8% | 23.0% | 29.1% | 11.9% | 03.6% | 05.6% |

| Between Canyon City and Sheep Camp | 26.8% | 30.0% | 30.0% | 06.5% | 01.0% | 05.8% |

| Between Sheep Camp and Chilkoot Pass | 26.6% | 25.1% | 30.2% | 09.7% | 02.4% | 06.0% |

| Between Chilkoot Pass and Lindeman | 29.3% | 25.7% | 26.1% | 11.3% | 01.8% | 05.7% |

| Between Lindeman and Bennett | 34.1% | 29.1% | 21.2% | 04.0% | 01.6% | 10.0% |

General statements about the Trail showed concern about wet feet: 48 hikers called the wet and muddy route a maintenance problem, and 36 blamed weather and terrain. Another 30 hikers felt that good weather improved the Trail conditions and hence their evaluation. The presence of bridges appealed to 26 hikers with another 14 indicating a need to improve them and build more. Over 20 hikers felt some of the roots and rocks needed to be removed so that the surface could be improved. An equal number found it difficult to evaluate the Trail, either having no basis of comparison because this was their first hike, or because they found it "irrelevant—a trail is a trail." Over 30 hikers found the Trail, and especially the Pass, "harder than expected," and much more difficult for beginners.

The previous comments have concerned the Trail as a unit, but many respondents identified their comments by the section of Trail they were evaluating. Over half of the 290 respondents who rated the section of the Trail between Dyea and Canyon City as "below average" or "inferior" identified the flooding near mile 6 and wetness in general as their major source of complaint. Many felt it was "hard to follow the detours" and that "bridges are needed." Another 88, although rating this section of the Trail as "average" or better, still commented on the wetness. There were minor complaints about the monotony of the logging road, the unpleasant signs of motorized vehicle usage, and the need to clear some foliage.

The section from Canyon City to Sheep Camp received less comment. Forty-eight hikers complained of wetness in this area. Among those who commented about the Trail between Sheep Camp and the Pass, wetness was only a minor concern, although snow was a problem early in the season. Over 80 hikers found that last half mile before the Pass was: "harder than expected;" "dangerous;" "steep;" "rocky;" "not really a trail;" and "hazardous especially in bad weather." Nine of these felt it especially difficult when they descended the Pass on the American side. However, 23 felt this section was "not so hard," was "well-marked," and was their "favorite part" of the trip.

The Trail from the Pass to Lindeman (which is also the longest section) received a good deal of comment, especially about the first mile after the Pass. The "unexpected danger of the steep snowfield," the "lack of a real trail," the "glacial outwash," and the "precarious rocks," were a source of concern to 106 hikers. Some of these found the Trail hard to follow at this point. About 70 hikers felt that more cairns and Trail markers were needed, especially in white-out conditions. Another ten sought fewer markers, or more consistent ones, and cairns were preferred over spray paint and aluminum poles, except where cairns were impractical. Fourteen hikers had problems following certain parts of this section, especially around Happy Camp, in places where two trails were evident, and where snow-melt had inundated the area. Another 14 liked this section the best, especially the scenery.

The Trail segment from Lindeman to Bennett received the highest ratings, since wetness and visibility were not problems. But 42 respondents did find the blazes on the trees "disgusting," "damaging," and "unnecessary." Seventeen hikers disliked the route because it went up and down for no apparent reason, it "seemed illogical," and was not historical. Ten hikers complained of roots, rocks, stumps, and a few wet spots. Thirty-four were concerned about the sandy part of the Trail near Bennett. They found it not only hard to walk on, but felt it was difficult to find the path especially when coming from Bennett. A few hikers noted that the trip to Bennett from Lindeman was too improved or boring after the challenge of the Pass.

| Table 28. How would you rate the physical condition of the shelters? (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Evaluation | ||||||

| Shelter | E | AA | A | BA | I | No information |

| Canyon City | 34.4% | 28.5% | 20.9% | 02.6% | 00.4% | 13.2% |

| Sheep Camp | 35.1% | 32.8% | 20.1% | 01.6% | 00.4% | 09.9% |

| Lindeman | 34.5% | 25.4% | 21.6% | 04.1% | 00.6% | 13.8% |

Finally, the shelters on the Trail received very high ratings overall. Over 250 general comments of praise were made: "appreciated," "welcoed," "cozy and nice," "well kept," "in excellent condition,"" and "pleasant surprise." Over 100 respondents indicated that, although they did not sleep in the shelters, they had used them for resting, drying clothes, cooking, and meeting people. Fifty-five hikers commented that shelters were unnecessary, especially in good weather, and that hikers should not depend on them. Yet they agreed that shelters were welcome in severe weather and needed for ill-prepared hikers. While 32 respondents said that no more shelters were necessary, 13 felt that more should be added at the present sites. At least as many hikers felt Sheep Camp or Canyon City was in need of more shelter space, while twice as many found the Lindeman cabins too small (often not realizing that there are two of them).

Dirty outhouses were a source of complaint for 42 hikers. Three-quarters of them singled-out the American outhouses, especially the one at Canyon City, as the worst. Many found the presence of mice annoying in the American shelters and felt hikers should be educated not to leave food behind. Other recommended solutions were: rangers enforcing the pack-in, pack-out policy and cleaning-up after hikers; food lockers; and burn pits. Other general complaints centered around the need for better tools and a well-supplied firewood pile.

Over 100 respondents indicated that they had not used the shelters, some feeling unqualified to rate them. Many felt they would have used shelter had they not been full, dominated by a large group or taken-over by a party as if it were a private cabin. They suggested one-night limits for the shelters and posted rules prohibiting the denial of access to the shelters for other hikers.

Each shelter was criticized for over 20 hikers for the poor wood-burning stoves, and by at least 25 for the uncomfortable bunks and limited bunkspace. Several found the shelters gloomy and buggy. Each shelter received its share of votes as a favorite. The cabins at Lindeman received over 60 of these accolades (five times more than each of the others), for their rustic appearance, "funky outhouses," ready wood supply, and pleasant location. These cabins, however, also received the most complaints about small size, sagging roofs, draftiness, and plastic windows. Sheep Camp was not only applauded for the logbook which provided good reading about other Chilkoot adventures, but also criticized for the lack of tent sites near the shelter.

Hikers were given the opportunity to state their views regarding certain management options for the Trail. They were asked to indicate their preference for these options by circling one of the following answer codes:

Strongly agree (SA)

Agree (A)

Neutral (N)

Disagree (D)

Strongly disagree (SD)

It was difficult for some respondents to give an opinion without stating certain qualifications, which were usually written on the margins of the questionnaire.

| Table 29. Opinions on motorized vehicles and boats for the Trail (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| Motorized vehicles should not be allowed on the Trail. | 92.8% | 01.7% | 00.3% | 00.7% | 04.3% | 00.3% |

| Motorized boats should be allowed on the lakes. | 14.6% | 05.0% | 07.5% | 11.8% | 60.5% | 00.7% |

Most of the respondents did not approve of motorized vehicles on the Trail nor of motorized boats on the lakes. Yet some respondents did support motorized vehicles and boats (especially the latter) for use by the staff, but primarily for emergency situations. Some of those who supported motorized boats agreed on limiting the horsepower. A few respondents also encouraged banning seaplanes and chainsaws. One hiker suggested that the cable crossing at Finningan's Point be rebuilt. One hiker probably spoke for the majority when he wrote: "without some sweat and strain, the accomplishments of the stampeders cannot be appreciated."

Most hikers did not want to have horses on the Trail, but their opinions were evenly split regarding the presence of dogs. [44] Most comments about the use of horses emphasized their negative impact on the Trail. Some local horse packers who brought their animals on the American side of the Trail in the summer of 1976 indicated that they had assisted and would continue to assist with Trail repair when necessary. Some respondents opposed to the presence of dogs on the Trail commented that they disturb wildlife and bother hikers. Other comments mentioned that the Trail might be too difficult for dogs. In fact, one hiker wrote that the Trail "was hard on our two dogs' feet."

| Table 30. Opinions on the presence of horses and dogs on the Trail (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| Horses should not be allowed on the Trail. | 54.0% | 15.8% | 17.8% | 07.5% | 04.4% | 00.5% |

| Dogs should be allowed on the Trail. | 20.2% | 19.4% | 25.6% | 12.6% | 21.7% | 00.4% |

During the Gold Rush days on the Trail, the stampeders were screened at the Pass by the Canadian Mounties. Each stampeder was required to bring 1,100 pounds of supplies upon entering Canada en route to the Klondike gold fields. There has been much discussion recently among concerned persons as to whether the Trail rangers and patrolmen should likewise screen Chilkoot hikers today. As we suggested in the first section, some hikers were newcomers to backpacking. Furthermore, when asked if they were prepared to hike the Trail, 15 percent of the respondents indicated that they were unprepared in terms of hiking experience, while ten percent felt they were out of-shape, and nine percent mentioned that they were not properly equipped for the hike. [45] Almost three-quarters of the hikers who felt unprepared indicated such for the three situations: hiking experience, physical condition, and hiking equipment. When asked their opinions on whether patrolmen and rangers should forbid people who are improperly equipped or in poor physical condition to hike the Trail, approximately one-half of the respondents answered affirmatively, while close to 20 percent were neutral on the subject. Sixty-three hikers, however, commented that a policy of screening hikers would be difficult to implement, and 22 respondents suggested that this action would ilmpinge on a hiker's freedom. (Two of last summer's hikers were polio victims with crippled legs, yet they traveled the Trail with all the rest). On the other hand, 45 respondents felt that the Trail staff should do their utmost to warn hikers of the difficulties (and to strongly suggest turning back in certain cases) and to inform them of precisely what is needed to hike the Trail in safety. A few respondents wrote that hikers should be responsible for their own safety. As one person commented: "even the inexperienced have a fantastic experience." Almost 70 percent of the hikers supported daily patrol of the Trail by patrolmen and rangers, but nine percent cast negative votes on this issue. Some of the respondents wrote marginal comments, commending the Trail staff for their good work. Some of those disagreeing with this option were concerned with patrol frequency, suggesting that patrols be made during high-use periods and inclimate weather only. A few mentioned that patrols were comforting and reassuring for the hikers, as well as protecting the resource (both natural and historical). Others hoped that the patrolmen and rangers would patrol unobtrusively.

| Table 31. Opinions on rangers and patrolmen screening hikers and daily patrols by rangers and patrolmen (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| Rangers and patrolmen should not allow hikers who are improperly equipped or in poor physical condition to hike the Trail. | 19.2% | 28.3% | 21.7% | 19.3% | 09.9% | 01.6% |

| Trail rangers and patrolmen should patrol the Trail every day. | 32.6% | 33.8% | 24.3% | 06.4% | 02.3% | 00.6% |

The opinions of respondents were evenly distributed regarding management policies on limiting or restricting use of the Trail. There did appear, however, to be a slight bias in the affirmative towards limiting party size, but there was disagreement with the policy of restricting camping only to designated areas. Opinions on these two subjects were far stronger at the extremes (larger percentage for SA and SD, respectively) than for the other subjects. Sixty-eight hikers, regardless of their opinions, commented that limiting the number of hikers on the Trail was not necessary now but might be in the future. Some questioned how limits or restrictions might be imposed, while others were concerned that limits would infringe on personal freedom. A few even alluded to the fact that historically there were no limits. A number of respondents felt that camping restrictions would be needed in the event the impact on the resource was severe.

| Table 32. Opinions on limiting and restricting hikers on the Trail (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| The number of hikers on the Trail at any given time should be limited. | 12.2% | 25.2% | 22.2% | 24.6% | 13.8% | 02.0% |

| The number of hikers in camping areas at any given time should be limited. | 10.7% | 28.6% | 20.1% | 26.3% | 12.3% | 02.1% |

| Size of hiking parties should be limited to 1.2 persons. [46] | 23.4% | 23.6% | 17.5% | 21.1% | 13.2% | 01.3% |

| Camping should be allowed only in designated areas. | 13.8% | 18.2% | 10.0% | 32.7% | 24.0% | 01.4% |

Certain suggested facilities for the Trail (outhouses, shelters, bridges, cabins) seemed generally acceptable to hikers, but they questioned the appropriate ness of tables and permanent fireplaces. The issue of a shelter on the Canadian side of the Trail near the Pass became a running dialogue throughout the summer. Those interested in such a facility tended to be hikers who had camped between the Pass and Lindeman and who had experienced bad weather in the area of the Pass. Where exactly to locate such a shelter and what type of shelter to build were matters of interest.

| Table 33. Opinions on facilities for the Trail (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| The following facilities are appropriate in designated areas on the Trail: | ||||||

| Outhouses | 33.2% | 45.8% | 10.7% | 05.0% | 03.4% | 02.0% |

| Shelters | 32.2% | 50.7% | 09.2% | 04.7% | 01.7% | 01.5% |

| Bridges | 44.5% | 43.0% | 06.8% | 02.9% | 01.1% | 01.7% |

| Cabins for rangers | 29.3% | 43.9% | 20.0% | 02.0% | 01.9% | 02.9% |

| Tables | 14.7% | 25.7% | 24.3% | 21.1% | 12.1% | 02.1% |

| Permanent fireplace | 19.8% | 31.1% | 19.7% | 16.3% | 11.0% | 02.1% |

| An additional shelter should be built near Chilkoot Pass on the Canadian side of the Trail. | 38.5% | 27.4% | 12.9% | 08.6% | 10.1% | 02.4% |

Most people in favor of a shelter preferred one near the Pass, but others suggested locations in Happy Camp and near Crater Lake. Some respondents preferred a simple rock lean-to with no bunks, while others wished a shelter similar to the existing ones. Hikers mentioned the distance between Sheep Camp and Lindeman and the need to stop somewhere in-between as reasons for wanting another shelter on the Canadian side of the Trail. Others felt a structure was needed near the Pass to act as shelter against the rain and cold wind. This need was especially stressed to cope with possible emergencies. Those in disagreement with the shelter idea were concerned with negative impact on the resource and the view. They also felt that another shelter might influence hikers not to bring tents. As this issue continues to be debated, it should be remembered that over 60 percent of the hikers of 1976 camped at least one night between Sheep Camp and Lindeman (see Table 20). [47]

Respondents were generally in favor of retaining the historical flavor of the Trail, except when this maintenance would reach the extremes such as restoring the tramway. There appeared to be confusion with the use of the word "restoration." Some thought in terms of preservation. Marginal comments qualified support for restoration with: "a few sites only;" "if rustic, not fake;" "if unobtrusive;" "not museums." In other words, while respondents were generally supportive of the Trail following the historical trail (when possible), they did not want management to go so far as to reconstruct the tramway. Hikers voiced objection to restoration if it would appear fake or plastic, perhaps fearing a "Disneyland" effect, but felt that some protective measures were necessary. Many felt that finding artifacts in place and watching nature recapture that area greatly enhanced their experiences. Despite probable losses due theft and future deterioration, they felt that the most effective way to display the flavor of the Chilkoot was to leave the relics to be "discovered" by hikers and to decay naturally. Others favored subtle preservation of artifacts where they lie through wood treatments, while still others argued for artifact removal to museums or shelters on and off the Trail. Finally, formal interpretive programs were found more unacceptable than acceptable, although 35 percent were neutral on the matter. It should be noted, however, that in 1976 rangers, patrolmen, and hikers did participate in impromptu gatherings during which information about the Trail was exchanged. Some respondents mentioned certain alternatives to formal programs, ranging from personal research before the hike to pamphlets explaining a self-guided tour. For many hikers, the hike itself was the best historical interpretation.

| Table 34. Opinion on restoring and interpreting the Trail's history (N = 1,352). | ||||||

| Opinion | ||||||

| Management option | SA | A | N | D | SD | No information |

| Historical landmarks along the trail should be restored. | 25.3% | 28.6% | 18.7% | 16.1% | 09.5% | 01.9% |

| The Chilkoot Trail should have a tramway as in the Gold Rush days. | 03.5% | 05.6% | 12.8% | 21.7% | 55.1% | 01.32% |

| The Chilkoot Trail should follow the original historical trail. | 36.8% | 37.0% | 20.6% | 03.1% | 00.4% | 02.1% |

| Trail rangers and patrolmen should present evening interpretive programs on Klondike Gold Rush history in the camping areas. | 09.4% | 19.4% | 35.3% | 21.1% | 14.0% | 00.9% |

Although people had many complaints and suggestions about the Trail and the facilities, the overall message from hikers was one of satisfaction. Almost 350 people used the space provided in question #48 to report that their experience of hiking the Chilkoot Trail was "unforgettable," "fantastic," "educational," "incomparable," "enjoyable," "beautiful," "stimulating," "gratifying," "marvelous," and "rewarding." Hikers were proud of their "accomplishment," feeling that they had faced a "challenge" and despite difficulties had succeeded, and deserved a "pat on the back." The balance between "feeling history" and a backcountry experience was appreciated. Several hikers felt the trip was worth recommending to others. Fifty-six stated that they would like to hike the Trail again. Some of these hikers had turned back because of weather and injuries. Those who planned to return often wanted to share the experience with family and friends. Some wanted to allot more time, since they felt rushed on their first trip. Many of these laudatory remarks were also expressed in the guest books found at Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and Lindeman.

Over 220 hikers wanted the experience of traveling the Chilkoot to remain pretty much the same. They said: "leave the Trail alone;" "don't commercialize it;" "don't develop it;" "don't turn it into Disneyland;" "don't dilute the experience;" "don't build more facilities;" and "don't change it." Many felt that the historical significance of the hike would be lost if the Trail was improved. Among those who expressed this "leave it alone" sentiment were several who qualified their remarks with suggestions for minor improvements. These most often indicated a need for an additional shelter near the Pass, more trail markers and mile signs, a few more bridges, and a small amount of maintenance. Most hikers merely listed the few changes they found necessary, but 20 hikers declared an outright need for improvements in order to make the Chilkoot Trail acceptable to them. At the other extreme, 40 hikers suggested removing the facilities to make the Trail more natural and rugged. This, they felt, would also eliminate crowding problems and stop trail deterioration. Most hikers who were concerned with these issues saw them as future problems. Among the 50 people who commented about crowding, more than half felt this was not a concern now. Increased popularity of the Trail was an expected result of attaining national park status, and with it came fears of over management. While 31 hikers expressed disfavor with rules and restrictions, more than half of the respondents saw these as necessary if the Trail begins to show signs of deterioration. Park status itself was discussed. Sixteen hikers were skeptical of park policies toward changing the Trail, and 18 were glad for the added protection of the area.

Another major issue that emerged in hikers' comments is the need for more detailed, more accurate and more readily available information, including interpretation. Over 200 people specifically requested this, and the underlying message expressed by many others also pointed to the need, suggesting that better information might be a solution to many management and hiker concerns. Among those who requested more information, 60 stated that it needed to be available in more locations, but especially in Whitehorse, Skagway, and at the trailheads. Another 60 desired more accurate warning about the dangers of the trip including a specification of the necessary equipment, the prevalent weather conditions and the Trail's terrain. Over 30 hikers wanted a good topographic map and 18 wished more information on the natural history of the area. The new guidebook was criticized by 42 hikers because there were errors and inadequate information in it. Although not requesting information directly, 55 hikers felt that rules and policies about littering and trail and artifact protection need to be "clarified," "enforced," "advertised," or "stressed," since they are now confusing. Since it is always difficult to summarize adequately the comments of questionnaire respondents, we encourage the reader to turn to Appendix 3 to read a sample of comments written by Chilkoot hikers.

Overall, hiking the Chilkoot Trail during the summer of 1976 was a superb experience for almost all of the hikers. They enjoyed the unique combination of the Trail's historical and natural resources as well as the camaraderie which emerged on the Trail. And occasionally, as hikers trudged over the Pass enveloped in fog or as they fell asleep in their tents or the shelters, they could hear the sound of men and animals struggling up the Pass or the strains of honky-tonk music and laughter drifting through the night. For these reasons, the predominant message to Parks Canada and the National Park Service from the hikers was: "keep the Trail as is;" "leave it be;" and "no major changes."

|

| Interpretive sign on the trail near Lindeman |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

chilkoot-trail-hikers/overview.htm

Last Updated: 27-May-2011