|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hard Drive to the Klondike Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush |

|

CHAPTER ONE

"By-and-By": The Early History Of Seattle

"In a sense, Seattle itself arrived on the steamer Portland."Ross Anderson, The Seattle Times, 1997

Founding the City

Seattle has a long history of profiting from gold rushes. Beginning with the stampede to California in the mid-nineteenth century and continuing through the Klondike craze of 1897-1898, Seattle business interests were quick to spot economic opportunity. The California Gold Rush rapidly expanded the development of San Francisco in the early 1850s, opening a market for the lumber that grew in abundance in the Puget Sound region. Seattle's first business was a sawmill located at the foot of what is now Yesler Way. "You have the timber up there that we want and must have," one California miner advised an early Seattle resident. "By selling us lumber ... you'll soon be rich." [1] The city's founders swiftly recognized the potential value of the area's natural resources. They named their initial settlement in what is now West Seattle "New York-Alki," reflecting their ambition that "by-and-by" it would enjoy a prosperity rivaling that of the large cities on the eastern seaboard. [2]

The Denny party, which included 24 people led by former Illinois resident Arthur Denny, first settled on Alki Point in 1851. They arrived aboard the schooner Exact on a dreary November day. As many historians have recounted, some of the party's women responded to the wet, unfamiliar landscape by weeping. [3] This site proved to be unsuitable, prompting Denny, Carson Boren, and William Bell to explore the sheltered shoreline of Elliott Bay to the east. Here, in February of 1852, they chose a new location for their town, calling the site "Duwamps," after the nearby Duwamish River. That summer, they changed the name to Seattle, after the Indian leader Sealth. [4]

The new settlement consisted of an eight-acre island bordered by a saltwater lagoon to the east, and tideflats to the south. The settlers' initial claims ran from the foot of what is now Denny Way south to the island, near the intersection of First Avenue and King Street. The island's high point was located between Jackson and King streets on First Avenue. Throughout the nineteenth century, Seattle residents filled the surrounding tidelands, which today stand approximately 12 feet above the high-water level. [5]

Shortly after the members of the Denny party had staked their claims, Dr. David Swinson (known as "Doc") Maynard arrived. Perhaps the most colorful of Seattle's pioneers, he headed west from Ohio in 1850, hoping to escape a bad marriage and to strike it rich in the California gold fields. [6] "The first entry in his travel diary," observed historian Murray Morgan, "expressed the intention of many another man who eventually settled in Seattle: 'Left here for California.'" [7] A personable, gregarious, and "hard-drinking" man, Maynard was also a "buyer and a seller." In 1852, he settled in Seattle, where he opened the first store. He established a 58-block tract that included part of the island and the lagoon, and joined other settlers in donating land to Henry Yesler for the creation of a sawmill. [8] Maynard served as a physician, justice of the peace, and the town's first booster. [9] As historian Roger Sale explained, he "was willing to do anything to make Seattle grow." [10]

Yesler's business became the hub of Seattle's economy, and the new town's labor force expanded. Workers skidded enormous trees down Mill Street -- or "Skid Road" (now Yesler Way), to be cut into lumber. In 1854, Yesler constructed a wharf, and he began depositing sawdust from his mill into the bay and saltwater lagoon, thus increasing the land base along the waterfront. He also built a cookhouse, which became Seattle's first restaurant, along with a hall that became the town's meeting place. [11] By 1860, Seattle's population had reached approximately 150 residents. The commercial district on First Avenue South ran four blocks, from Yesler's mill to King Street. The city, incorporated in 1865, began to address the transportation problems created by the wet climate, which turned dirt streets into impassable bogs. Road crews planked Third Avenue with wood, marking the eastern border of the town. [12]

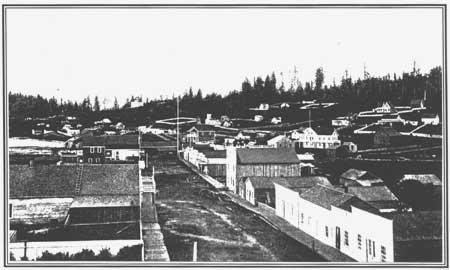

Seattle, 1856.

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social

Triends in Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1944)]

In 1869, when Seattle received its first charter, Yesler became mayor. Like Maynard, he hailed from Ohio. In contrast to Maynard, however, he remained "dour and tight-fisted," eventually selling his sawmill to pursue a more lucrative career in real estate. In Sales' estimation, had Seattle been settled mostly by people like Yesler, it would have evolved into little more than a company town rather than the largest city on Puget Sound. [13]

From the outset, Seattle's character differed from that of other early communities on Puget Sound, such as Port Gamble. According to numerous historians, Arthur Denny embodied the nature of this difference. A man with "an innate business sense," he had left his home in Illinois to take advantage of the opportunities that the West presented -- and he realized the economic connection between Seattle and San Francisco very quickly. During the early 1850s, ships arrived from California loaded with merchandise to be sold on commission in Seattle. Denny found a way to keep the profits by building a store on the corner of First Avenue and Washington Street, and purchasing stock directly in San Francisco. His entrepreneurial activities helped "reduce San Francisco's hold on Seattle." [14]

Throughout the remainder of his life, Denny engaged in a variety of businesses, ranging from banking to producing building materials. He also surveyed and platted much of the downtown area, donating land for establishing a university. Perhaps the best example of Denny's foresight was his interest in the railroad and his efforts to expand Seattle's transportation system, described below. Taken individually, these activities were not unique in burgeoning western communities. What set Denny apart was the extent of his "energy and vision." When he saw a need in the community, he stepped in to fill it, sometimes turning a handsome profit in the process. Even so, he was motivated by more than money, "feeling the growth of his own property to be a part of the growth of Seattle." Denny's activities led to "a decreasing dependence on the outside world for Seattle's essential livelihood," paving the way for future development. [15] He thus represented the vitality and the entrepreneurism that would characterize Seattle later in the century -- qualities that would place the city in an advantageous position during the Klondike Gold Rush era.

Seattle, early in 1856, from Main Street and First Avenue

South, looking north.

[Source: Clarence B. Bagley, History of

Seattle from the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time

(Chicago:

S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1916]

Early Local Industries

The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 encouraged settlement of the Pacific Northwest. This early homestead measure offered each white male adult 320 acres of land if single, and if he married by December 1, 1851, his wife was entitled to an additional 320 acres in her own right. To take advantage of this measure, settlers were required only to reside on the land and cultivate it for four years. [16]

Seattle further benefited from its proximity to farmlands in the Duwamish Valley. While the town's lumber industry developed during the 1850s, farmers staked claims along the river and prairies as far south as Auburn. Here they raised livestock and a variety of crops, including wheat, oats, peas, and potatoes, which they traded with Seattle settlers. [17]

Probably no development proved more influential to the early growth of Seattle than the arrival of the railroad. Arthur Denny realized the importance of connecting the town by rail line from the outset of his settlement on Puget Sound. His dream was delayed, however, by conflicts with Indians during the 1850s, and by the opening of Kansas and Nebraska for homesteading, which diverted potential settlers. During the 1860s, the Civil War further slowed railroad development in the West. Denny's hopes were rekindled in 1870, when the Northern Pacific Railroad began building a road west from Minnesota and a branch line from the Columbia River to Puget Sound. To help finance construction, the federal government gave the Northern Pacific the rights to millions of acres of land. [18]

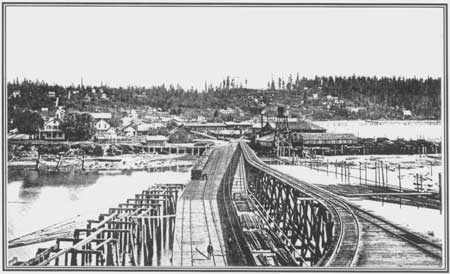

The Columbia and Puget Sound Railway Terminals on King Street

and Occidental Avenue about 1883.

[Source: Clarence B. Bagley, History

of Seattle from the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time

(Chicago:

S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1916)]

Seattle and Tacoma competed for the position as terminus for this transcontinental railroad. In 1873, Seattle residents urged the Northern Pacific to build its terminal in their town, extending offers of $250,000 in cash and 3,000 acres of undeveloped land -- much of which was located along the waterfront. The railroad company, however, decided to make Tacoma its terminus, owing to the greater opportunities for land speculation that the "City of Destiny" to the south presented. As The Oregonian, a Portland newspaper, explained, Tacoma became a company town, "largely the creation of the Northern Pacific" for "the benefit of some of its managers who compose the Tacoma Land Company." [19] Disappointed Seattle residents, including Denny, formed the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad, resolving to build their own connection over Snoqualmie Pass. On May Day of 1874, they organized a picnic and started laying track. Historians came to view this "bold and amusing" incident as reflecting a distinctive "spirit" in Seattle, characterized by optimism and determination. [20]

The effort to build a rail line from Seattle across the Cascade Mountains soon languished, due to lack of funds. Similarly, the Northern Pacific had collapsed in 1873, when Jay Cooke, its financier, went bankrupt. [21] Meanwhile, the discovery of coal deposits south and east of Seattle further encouraged city residents to develop local rail lines. By the 1870s, Seattle had nearly exhausted its supply of timber -- and the coal located in Renton, on the southern shore of Lake Washington, presented the opportunity for an additional export. In 1876, James Colman purchased Yesler's wharf, taking over construction of the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad. He extended the rail line to Renton and Newcastle, and Seattle began sending coal to markets in Portland and San Francisco. Trains carried coal across the tideflats, to docks on Elliott Bay. The rail connections, along with deposits discovered in Issaquah and Black Diamond, helped make coal a significant export, second only to lumber. So significant was the development of coal that Seattle came to be called "the Liverpool of the North." [22]

During the 1880s, Seattle enjoyed its "first great spurt of growth.." [23] Residents established a chamber of commerce to promote business interests in 1882, and five years later the Northern Pacific Railroad completed its transcontinental line to Tacoma, thus linking Puget Sound to the markets of the eastern United States. The railroad also helped make Seattle accessible to migrants, who traveled north from Tacoma on a branch line. [24] As the mayor of Seattle, Henry Yesler viewed these railroad connections with considerable enthusiasm. He predicted in 1886 that "in the near future more than one transcontinental railroad will be humbly asking for our trade and support." So bright were Seattle's prospects that Yesler downplayed its competition with Tacoma. Once the transcontinental railroad reaches Seattle, he suggested, "it will be a matter of wonder that any other city upon Puget Sound ever dreamed of being our rival, far less our superior." [25] By 1888, a tunnel through Stampede Pass, which cut through the Cascade Mountains, had allowed for direct rail service from eastern points to Seattle.

During the 1880s, the city's population expanded from 3,500 to more than 43,000. [26] Rapid growth had its drawbacks, at least from an aesthetic perspective. Ernest Ingersoll, a writer who visited Seattle at this time, characterized it as "scattered" and disorganized. "The town has grown too fast to look well or healthy," he informed readers of Harper's New Monthly Magazine. "Everybody has been in [such] great haste to get there and get a roof over his head that he has not minded much how it looked or pulled many stumps out of his door-yard." [27]

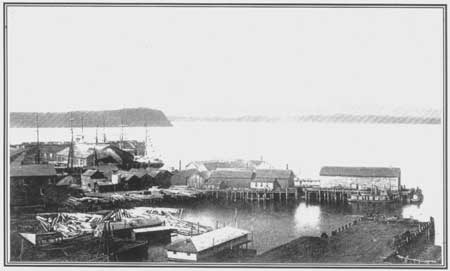

Yesler's Wharf about 1885.

[Source: Clarence B. Bagley, History

of Seattle from the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time

(Chicago:

S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1916)]

Seattle's commercial district remained centered around the waterfront, which, by the late 1880s, had featured a patchwork of piers and frame buildings extending over the bay. [28] While developing its rail connections, the city relied heavily on maritime traffic -- some of which focused on the Far North, due to an increasing commercial interest in the region's fur seals and fisheries. Although the Alaska Commercial Company was based in San Francisco, by the 1880s, Seattle also had become a center of water trade between Puget Sound and the Far North. [29] The construction of "larger and better wharves" and improved shipping facilities hastened this transition. [30]

The Pacific Coast Steamship Company provided the first direct, regular service from Seattle to Alaska in 1886. During the mid-1890s, the Alaska Steamship Company formed in Seattle, and the Japan Steamship Company placed its western American terminus at the city, contracting with the railroad for exchange of freight and delivery. This development represented an "immense advance in the commerce of the city." [31] When the Japanese steamship Miiki Maru sailed into Elliott Bay with a cargo of silk and tea in 1896, the Seattle city council declared a holiday. [32] In the years before the Klondike Gold Rush, then, Seattle established a trade link with Alaska and the Far North as well as with the Far East.

A variety of shipping company offices were located along First Avenue South , which also supported such businesses as meat packing, food processing, furniture manufacturing, and breweries. These industries served Seattle residents as well as the outlying logging, farming, and mining communities. [33] City laborers found lodging in hotels, tenements, and boarding houses located off Main Street. [34]

During this era, Seattle included a Chinese community, located initially in the area around First Avenue South and Occidental Avenue. Chinese immigrants came to the Northwest in the 1870s, to work on the region's rail lines and in its mines. For the next two decades, they also labored on regrading projects and in laundries, canneries, and stores. By the 1880s, the Chinese community had moved to Washington Street, between Second and Third avenues, where residents often lived above stores and retail businesses. Anti-Chinese sentiment, encouraged by white laborers, erupted in riots during the mid-1880s, prompting declaration of martial law. Before troops arrived, many Chinese workers were evicted from the city. Those remaining in Seattle continued to live along Washington Street, where they were joined by an influx of Japanese workers. [35]

Most of the town's infrastructure -- including streets, wharves, businesses, and residences -- was made of wood. In 1889, however, Seattle had the opportunity to rebuild itself. On June 6 of that year, a devastating fire swept through downtown, beginning in a store on the corner of First Avenue and Madison Street eventually destroying more than 30 blocks. Although destructive, this blaze resulted in new development, as Seattle passed an ordinance requiring that buildings downtown be constructed of brick and stone. [36]

|

Observers -- and investors -- noted that the fire sparked the "Seattle spirit" of optimism and determination. Seattle resident Judge Thomas Burke, for example, described the post-fire mood of the town as one of "vigor and energy." The flames "had scarcely been extinguished before the rebuilding of the City and the re-establishment of business in the various lines had been begun," he stated in July of 1889. "Banks have now on deposit more than they ever had before." [37] Early historians similarly praised the pluck and resolve of Seattle citizens for their swift response to the disaster. "Fate lit a torch," explained Welford Beaton in 1914, "which called to arms the enterprise and spirit of the people," who began the task of rebuilding "while the ashes were still warm." [38] Citizens in Seattle had further cause for optimism in July of 1889, when territorial delegates met in Olympia to draft a state constitution and by-laws. On November 11 of that year, Washington was admitted to the Union as the 42nd state. [39]

After the fire, the center of business activity in Seattle gradually expanded from Yesler's wharf to the north, east, and southeast. Neighborhoods emerged along the electric streetcar lines, established in 1884, that ran north and east from downtown. [40] Many residents lived in the core of the city, in the five blocks on either side of Yesler Way, between First and Third Avenues. According to Sale, downtown Seattle featured "furniture and cabinet makers, machine shops, groceries, laundries, dressmakers, meat and fish merchants, and in a great many instances the owners and employees of these businesses lived there or nearby." In short, "light industry and office work were next to each other, and both were next to all kinds of residences." [41] The presence of these various industries, along with the transportation infrastructure, helped business interests in Seattle take advantage of the opportunities presented at the onset of the Klondike Gold Rush.

The 1890s

The rebuilding of Seattle and the continued expansion of the town's infrastructure encouraged some residents to meet the 1890s with high expectations -- and the decade began favorably in Seattle. In 1890, The Overland Monthly, a national publication, characterized the industrial growth in Puget Sound as "very remarkable." [42] By that year, the population of Seattle had reached 40,000. According to The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, newcomers were attracted to the town's "independent enterprise and go-aheadiveness." [43] The decade began in Seattle with a "building boom" prompted not only by the fire but also by the arrival of James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway. Judge Burke persuaded Hill to select the town as the terminus for his transcontinental line, which reached Puget Sound in 1893. Historians would later view this event as monumental in significance for its contribution to the growth of the city's economy and infrastructure.

The 1890s, however, proved to be anything but gay. In 1893, unchecked speculation on Wall Street and overexpansion of railroads created the worst economic downturn that the nation had yet experienced. Europe, South Africa, and South America also felt the effects of what came to be known as the Panic of 1893. Frightened foreign investors sold their American bonds, draining gold from the U.S. Treasury. The prosperity in Seattle stimulated by the Great Northern Railway "collapsed with an abruptness that ruined thousands." [44] Edith Feero Larson, who lived in Tacoma during the Panic of 1893, later recalled that "the Northwest should have boomed with the completion of the railroads.... It did for a few months, then money began to disappear and no one had any work. For a while our papa cut firewood for the railway for a dollar a day -- a fourteen-hour day. 'It keeps us eating,' he said." [45] So dismal was the economic depression during the 1890s that one local historian has portrayed it as "the decade of misery." [46]

Economic hard times strengthened interest in the People's or Populist party throughout the Pacific Northwest. Populism appealed to voters who regarded the "Gilded Age" of the late nineteenth century with disenchantment. While the industrialization of the country after the Civil War had brought vast fortunes to a few individuals, the gap between the wealthy and the poor had widened considerably. The misery of the depression gave rise to unrest. In 1894 unemployed workers from the Pacific Northwest -- known as Coxey's Army -- marched east toward Capitol Hill, intending to demand jobs. The U.S. Army overtook these desperate men in Wyoming, after they had commandeered a train. That year, the Pullman strike also marked the first nationwide walkout by railroad workers. Corruption in government added to the dissatisfaction that fueled Populist sentiment -- and by the early 1890s unprecedented unemployment increased calls for reforms. These included government ownership of railroad, telegraph, and telephone lines as well as federal anti-trust legislation to curtail corporate power. [47]

One of the most prominent platforms of the Populist party became the free and unlimited coinage of silver by the federal treasury. The hope was that this inflationary measure would stimulate the national economy, while bolstering the flagging silver mining industry in the West. Opposition to the Free Silver Movement generally came from eastern-based bankers and financiers who favored the traditional hard money, or gold standard. Many voters in Washington state, however, embraced the Populist party -- especially after the Panic of 1893. [48] By 1896, The Seattle Daily Times had become a voice of the Populist party, advocating free coinage of silver. The newspaper's masthead supported laborers against "the silk-stockinged gentlemen" who favored the gold standard. [49]

In the presidential election of 1896, Washington and Idaho supported William Jennings Bryan, the Populist and Democratic candidate and an advocate of free silver. "You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns," he warned the opposition at the Democratic convention. "You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!" His words revealed that free silver had become "almost as much a religious as a financial issue." Even so, Republican "Gold Bugs" triumphed over what they regarded as the "silver lunacy," with their candidate, William McKinley, winning the presidency. [50] The advocacy of Free Silver as a means to alleviate the depression in the 1890s directed national attention to the discovery and mining of precious metals throughout the West and Far North, helping to set the stage for the Klondike Gold Rush. [51]

The anxious tone of the early 1890s was further reflected in Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis. Delivered in 1893 before a Chicago meeting of the American Historical Association, this bold interpretation of American history suggested the national identity had been shaped by the so-called "frontier experience." As Turner explained, "The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development." According to him, the expansion into western lands had transformed immigrants into self-reliant, independent, inventive Americans. The frontier, moreover, represented the opportunity for fresh starts. Turner's thesis touched a nerve in the 1890s, as the forces that he claimed had shaped the American character seemed to be fast disappearing. Three years earlier, the U.S. Census had declared the frontier to be "closed," ending an era in American history. As the Superintendent of the Census explained in 1890, "at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line." [52]

Scholars have debated Turner's thesis since it appeared in the 1890s. The New Western Historians in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, criticized its ethnocentric assumptions, pointing out that the "free land" Turner described was hardly a "frontier" to the Indian and Latino peoples already living there. [53] Even so, during the 1890s, Turner's thesis signaled a concern that the West no longer represented a land of promise or a safety valve for the laborers of the East. Although the number of Americans aware of it would have been limited in 1893, Turner's thesis exemplified "a growing perception that the frontier era was over." [54]

This concern was not limited to the perceived availability of western lands. The dispirited tone of the 1890s appeared in a variety of forums, including popular journals, which summarized the "mood of the age" as one of "pessimism." [55] As The Seattle Daily Times explained in 1897, "the great majority of the American people ... have suffered so much loss of property and the ordinary comforts of life, during the last four years." So "burdensome" had the economic hard times become "that endurance for another year seemed almost impossible." [56] For many Americans, the Klondike Gold Rush provided a welcome distraction. Although its precise impact on the depression is difficult to determine, the stampede became a focus for hope and expectation during the late 1890s -- even for those who did not leave for the Far North.

As the historian Roderick Nash pointed out, for many Americans the Yukon promised more than economic gain. The timing of the Klondike stampede, he explained in Wilderness and the American Mind, was particularly significant:

When the forty-niners rushed to California's gold fields in the mid-nineteenth century, the United States was still a developing nation with a wild West. The miners did not seem picturesque and romantic so much as uncouth and a bit embarrassing to a society trying to mature. But with the frontier officially dead (according to the 1890 census), the time was ripe for a myth that accorded cowboys and hunters and miners legendary proportions. Americans of the early twentieth century were prepared to romanticize the "ninety-eighters" and paint their rush to the gold of the north in glowing colors.

The image of the Far North as a wild, savage place proved appealing. The wide circulation of Jack London's novel, The Call of the Wild (1903), exemplified the popularity of this romanticized view of the gold rush. [57]

Gold Fever Strikes

Few events in the history of Seattle have produced more excitement than the stampede to the Yukon. Gold discoveries at Circle City and Cook Inlet in Alaska sparked a small rush in Seattle in 1896, but the fervor did not equal that generated by the Klondike strike. The discovery of gold in 1896 on Rabbit Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River, heralded a momentous era for the city. In July of 1897, the ships Excelsior and Portland docked in San Francisco and Seattle respectively, carrying three tons of gold between them from the Far North.The media lost no time in spreading the news, sparking the "Klondike Fever" that gripped much of the nation and Seattle for the next two years. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer produced one of the most memorable accounts of the Portland's arrival. The paper chartered a tug so that one of its correspondents could meet this vessel as it sailed, laden with gold nuggets, into Puget Sound. "GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!," the headline of July 17, 1897 read. "Sixty-Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland. STACKS OF YELLOW METAL!" [58] This would prove to be one of the most enduring images in Seattle's history, contributing to the city's identity. As one reporter observed 100 years later, "in a sense, Seattle itself arrived on the steamer Portland." [59]

|

The Seattle Daily Times conveyed the sense of excitement and exhilaration that swept the town. "All that anyone hears at present is 'Klondyke,'" it reported on July 23, 1897. "It is impossible to escape it. It is talked in the morning; it is discussed at lunch; it demands attention at the dinner table; it is all one hears during the interval of his after-dinner smoke; and at night one dreams about mountains of yellow metal with nuggets as big as fire plugs." [60] Similarly, the celebrated nature writer John Muir, hired by the San Francisco Examiner to describe the Far North, observed, "The Klondyke! The Klondyke! Which is the best way into the yellow Klondyke? Is all the cry nowadays." [61]

Confusion about the term "Klondike" added to the mystery of the gold fields. The press typeset the words "Klondike," "Klondyke," and "Clondyke," sometimes seemingly at random, although the Post-Intelligencer favored "Clondyke," while the Times preferred using a "K." In August of 1897, the U.S. government and the Associated Press chose "Klondike" as the official spelling. [62]

Whatever the spelling, it soon became clear what the word conveyed to readers. The national journal Leslie's Weekly, for example, reported that it "stands for millions of gold, and is a synonym for the advancement, after unspeakable suffering, of hundreds of miners from poverty to affluence in a brief period of a few months." [63] Four years of depression had increased the appeal of the gold fields. One ounce of gold was worth $16 in 1897 -- a year when typical wages totaled approximately $14 for 78 hours of work. Moreover, the Far North offered opportunity for adventure and exploration during an era that had witnessed the close of the "frontier." [64]

News of the Klondike strike quickly spread to the Midwest and East Coast, where stories of instant wealth were circulated with a vigor that matched the media coverage in the West -- at least initially. Two days after the Portland docked in Seattle, New York City was "touched" with gold fever. "Klondyke Arouses the East," announced The Seattle Daily Times on July 20, 1897. "Effete Civilization ... Affected by the Reports." New York City had contributed a large number of Forty-niners to the California Gold Rush, and observers expected it would again be well represented among the eastern argonauts headed for the Far North. [65] The New York Times reported the Klondike strike as monumentally significant. This publication quoted Clarence King, a celebrated geologist, as asserting, "The rush to the Klondike is one of the greatest in the history of the country." [66]

The Post-Intelligencer proved even more enthusiastic, describing the Klondike stampede as "one of the greatest migrations in the history of the world." [67] Both the Times and the Post-Intelligencer sent correspondents to the gold fields. Reporter S.P. Weston took a dozen carrier pigeons to send messages to the Associated Press and the Post-Intelligencer. [68] These Seattle papers also produced special Klondike editions, providing information on outfitting and prospecting. [69] Harper's Weekly, a national publication, sent special correspondent Tappan Adney to the Yukon to keep its readership informed, while The Illustrated London News sent Julius Price. [70]

The impact of this kind of media attention was immediate. Hundreds of spectators had crowded the waterfront in Seattle to greet the Portland. On July 18, 1897 -- just one day after that vessel arrived, the steamer Al-Ki departed for the Yukon, filled to capacity with miners and 350 tons of supplies. [71] As a Times headline explained on July 19, "Men With the Gold Fever" were "Hustling to Go." [72]

So strong was the lure of the Klondike that cities along Puget Sound had difficulty retaining employees. Much of Tacoma's fire department resigned to leave for the Yukon, while several Seattle policemen also quit. Some stores had to close because their clerks left abruptly for the Far North. The Rainier Produce Company lost its manager when news of the gold strike hit Seattle. [73] The labor shortage similarly affected the Seattle District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had difficulty retaining workers to complete its fortification projects in the Puget Sound region. "Due to the Klondike excitement," explained one contractor, it is "impossible to secure steady and reliable men in anything like adequate numbers." [74] Even Seattle's mayor, W.D. Wood, succumbed to gold fever, as did Col. K.C. Washburn, a King County and state legislator. "Seattle is Klondike Crazy," one San Francisco Chronicle headline explained on July 17, 1897. "Men of All Professions [Are] Preparing for the Gold Fields." [75]

Within a week, the Seattle city council raised the salaries of police officers, and the Post-Intelligencer issued a warning to job hunters that there was no labor shortage in the city, to prevent a rush for the abandoned positions. [76] The discovery of gold in the Yukon was even credited with lowering the crime rate in the Puget Sound area, "since the men who would ordinarily commit offenses against the laws of the city or state now have something else to think about." [77] These were crimes such as burglary, for the gold rush encouraged the development of vice-related offenses.

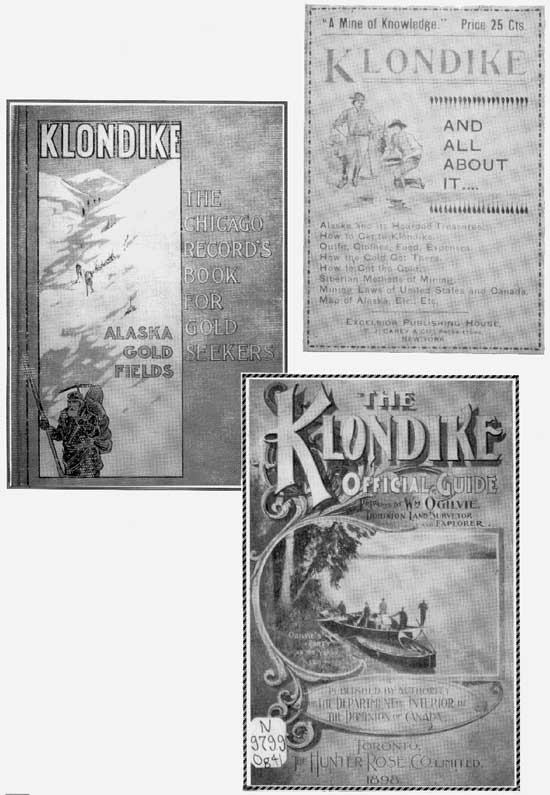

When the gold craze hit the nation, few Americans were familiar with the geography of the Far North. Many assumed that the Klondike was located in Alaska, instead of in the Yukon, in Canadian territory. Klondike guidebooks -- some of which were hastily produced in a matter of days -- further obscured the issue. The Chicago Record's Book for Gold Seekers, for example, used the terms "Klondike" and "Alaska Gold Fields" interchangeably. Blinded by visions of treasure, many prospective miners were ignorant of what a trip to the Far North would entail. [78] Upon hearing the news of the Klondike strike, a group of enterprising New Yorkers made plans to walk to the gold fields from the East Coast. [79] Similarly, one New York woman inquired upon arriving in Seattle, "Can I walk to the Klondike or is it too far?" [80]

(Courtesy of Terrence Cole)

Others planned to reach the Yukon by balloon. Charles Kuenzel, a resident of Hoboken, New Jersey, organized an airship expedition. "We may get lost away up in the air somewhere," he conceded. "The Western and Klondike country is strange to me, and I may make some mistakes in steering. There are no charts for the air. But I'll land all right." [81] Similarly, a group of enthusiastic Canadians planned to launch a "line of airships" to the Klondike. [82]

Although these whimsical, optimistic schemes can appear charming today, the stampede to the Klondike brought tragedy to many -- even to those who remained home. By 1898, the Seattle police had received hundreds of inquiries about missing persons. One distraught woman from Olympia reported that her husband had left for Seattle and was not heard from again. She feared he had fallen ill, or had become a victim of "the wicked part of the city." As The Times described the situation, "Children left behind and forgotten want to come to their fathers and mothers; old fathers in the East inquire for sons; wives in destitute circumstances for husbands; old, gray haired mothers write tear stained letters pitifully begging the Chief of Police to hunt up their wayward boys." [83]

The gold rush, according to the Post-Intelligencer, had resulted in a "Nest of Missing People." Clearly some gold seekers did [84] not want to be found. Even so, many died attempting to reach the Klondike -- and their identities were not always known. On a February evening in 1898, for example, the steamer Clara Nevada exploded and burned while en route between Skagway and Seattle. More than 70 of its passengers were lost, and aside from the crew it was not clear who was on board. [85] A month after the disaster, the ship's carpenter notified The Seattle Daily Times that although the newspaper reported his death, he remained "alive and hardy and well." [86]

The Klondike Gold Rush attracted approximately 100,000 miners, 70,000 of whom passed through Seattle, nearly doubling the population of the city. So extensive was this migration that the Post-Intelligencer ran a regular column titled "The Passing Throng." [87] Although the majority were white men, African-Americans traveled to the gold fields as well. Many women went, too, sometimes bringing their families. The Klondike Gold Rush was a multi-national event, attracting argonauts of various ages and ethnicity. [88]

For the most part, however, it was not the prospectors who profited from the stampede to the Klondike. Instead, it was the merchants who struck pay dirt, as the gold rush encouraged the development of businesses that outfitted and transported the miners. As noted, Seattle already had the transportation network, infrastructure, and local industries needed to benefit from the migration to the Far North. Seattle also benefitted from the farmlands, coal deposits, and forests in the surrounding area. All that was need was publicity promoting the city -- a theme that is analyzed throughout the following chapter.

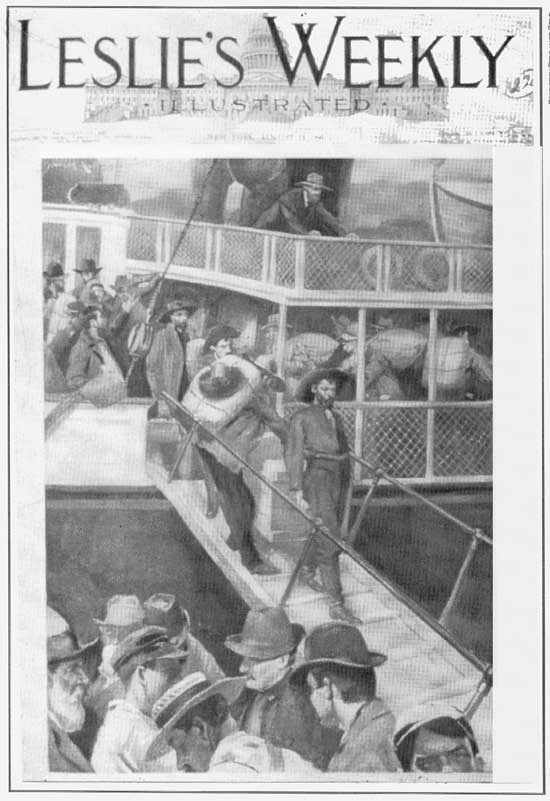

This illustration depicted Klondike miners arriving in Seattle

in 1897.

(Courtesy of Terrence Cole)

Klondike Guidebooks.

(Courtesy of Terrence Cole)

End of Chapter One

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003