|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hard Drive to the Klondike Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush |

|

CHAPTER TWO

Selling Seattle

"There is probably no city in the Union today so much talked about as Seattle and there is certainly none toward which more faces are at present turned. From every nook and corner of America and from even the uttermost parts of the earth, a ceaseless, restless throng is moving -- moving toward the land of the midnight sun and precious gold, and moving through its natural gateway -- the far-famed City of Seattle."The Seattle Daily Times, 1898

"We are taking advantage of the Klondike excitement to let the world know about Seattle."

Erastus Brainerd, 1897

Erastus Brainerd and The Seattle Chamber of Commerce

Seattle's reputation as the gateway to Alaska and the Far North is widespread. Alaska Airlines remains based in this city, providing a modern example of the transportation connections that were established in the late nineteenth century. As historian Murray Morgan observed, Seattle residents "tend to look on Alaska as their very own....Seattle stores display sub-arctic clothing, though Puget Sound winters are usually mild; Seattle curio shops feature totem poles, though no Puget Sound Indian ever carved one." [1] This perception is in part a legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush, which linked Seattle and the Far North in the public mind. It resulted from an extensive advertising campaign designed and launched by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce in 1897.

From the outset of the gold rush, Seattle newspapers promoted their city as the obvious point of outfitting and departure for the Yukon. "If there ever was competition between Seattle and other cities on the Pacific Coast relative to Alaska business," The Seattle Post-Intelligencer boasted on July 25, 1897, "it has entirely disappeared....Seattle controls the trade with Alaska. There is no other way to state the fact -- the control is complete and absolute." As the Post-Intelligencer concluded, the rush to the Klondike was "centered in Seattle." [2] Despite such bold assertions, however, it took the Seattle Chamber of Commerce months of effort in public relations to make this "fact" a reality. Comprised of only seven key members, it proved to be a very vocal force in promoting Seattle.

Cooper and Levy -- a major outfitter in the city -- moved Seattle boosters to action. One of the owners notified the Chamber of Commerce that railroad companies were not routing many of the early Klondike stampeders through Seattle. Initially, only the Great Northern Railway took Yukon-bound passengers to this city, while the Southern Pacific routed passengers to San Francisco, the Northern Pacific advertised Portland, and the Canadian Pacific promoted Vancouver, British Columbia. The Chamber of Commerce thus established the Bureau of Information on August 30, 1897, to devise a plan for promoting Seattle as the Klondike outfitting and departure center. It also charged the Bureau of Information with counteracting the efforts of other cities in this direction. Even more significant, members appointed Erastus Brainerd as secretary and executive officer. [3] Were it not for this move, Seattle might not have figured as prominently as it did in the Klondike trade.

Brainerd proved to be the most influential of Seattle's boosters during the Klondike Gold Rush. What was most remarkable about his advertising campaign was that it was waged during an era before the practice of swaying public opinion had become commonplace. His social status and his professional contacts helped his publicity efforts. Born in the Connecticut River Valley in 1855, Brainerd attended Phillips Exeter Academy, and graduated from Harvard at the tender age of 19. After serving as curator of engravings at the Boston Museum of Arts, he traveled to Europe, where he promoted a tour for W. Irving Bishop, a "lecturing showman." While in Europe, Brainerd displayed his gregarious personality and his propensity for joining, becoming a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, a Knight of the Red Cross of Rome, a Knight Templar, and a Mason. [4]

|

Returning to the United States, Brainerd turned to journalism, landing a job as a news editor of the Atlanta Constitution. In 1882, he married Jefferson Davis' granddaughter, which endeared him to Southern readers. One reporter described Brainerd at this time as "an accomplished gentleman, a desirable citizen, and an engaging friend." Moving to Philadelphia, Brainerd again joined a variety of organizations, including the Union League, Penn Club, and the Authors and Press clubs of New York. [5]

In 1890, Brainerd suffered from several attacks of influenza. His desire for employment opportunities as well as his ill health prompted him to relocate to Seattle, where he became the editor of The Press-Times. Brainerd joined the Rainier Club and organized a local Harvard Club, becoming known as "a social swell and an authority on terrapin [edible turtles]." His activities included fishing trips with the eminent Judge Thomas Burke. By 1897, when Brainerd became secretary of the Bureau of Information, he had developed valuable social -- and editorial -- connections in the Puget Sound area and throughout the nation. As one biographer summarized, Brainerd was a "man of the world, confident and self-assertive." He was also an "unusually facile writer"-- a characteristic that would serve Seattle well in the publicity campaign. [6]

The Advertising Campaign

Brainerd's strategy was to promote the city as the only place to outfit for the Klondike. He devised a plan to finance the Bureau of Information by taxing Seattle merchants who stood to profit from the expected influx of population and increased trade. [7] Businesses that paid dues received lists of prospective customers. Brainerd devoted some of this money to advertising in newspapers and popular journals. He purchased a three-quarter-page ad in William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal for $800, along with quarter-page advertisements in Munsey, McClure's, Cosmopolitan, Harper's Weekly, Scribner's, and Review of Reviews. [8] One of these advertisements pointed out that as the "Queen City of the Northwest," Seattle served as the manufacturing, railroad, mining, and agricultural center of Washington state. "Look at your map!" the ad urged readers. "Seattle is a commercial city, and is to the Pacific Northwest as New York is to the Atlantic coast." [9]

Brainerd also encouraged the Post-Intelligencer to issue a special Klondike edition on October 13, 1897, which began with the headline, "Seattle Opens the Gate to the Klondike Gold Fields." Seattle, the lead article assured readers, "is not a mushroom, milk-and-water town with only crude frontier ways." Instead, "it is a city of from 65,000 to 70,000 population, with big brick and stone business blocks and mercantile establishments that would be a credit to Chicago, New York, or Boston." The issue featured a map of transcontinental railroad lines leading to Seattle, "the Gateway." [10]

This map, which appeared in The Seattle Post

Intelligencer in October 1897, depicted "all the great rail

lines" leading to Seattle. San Francisco, Vancouver, and other

rival cities -- which also offered rail connections -- did not

appear.

|

Routes to the Klondike

(Courtesy National Park Service)

The special Klondike edition offered advice to prospectors on what to bring to the gold fields, how to obtain an outfit, and which route to select. It provided much of the same information as the guidebooks produced throughout the nation during the late nineteenth century, while promoting Seattle.

[Source: Erastus Brainerd Scrapbook, University of

Washington]

For a week preceding the publication of the special Klondike edition, Brainerd placed advertisements announcing the upcoming issue and urging readers to send copies to friends and relatives in the East. The Post-Intelligencer printed 212,000 copies, making it the largest newspaper run that had been produced west of Chicago. Brainerd sent more than 70,000 to postmasters across the nation, requesting that they distribute them. Various newspaper editors received 20,000 copies, while 10,000 copies went to librarians, mayors, and members of town councils. The Great Northern Railway and Northern Pacific received 10,000 and 5,000 copies respectively. [11]

In addition, Brainerd wrote feature stories on Seattle's virtues, which he distributed to publications throughout the nation. "The 'Seattle Spirit' has accomplished wonders," he assured readers of The Argus in 1897. "My impression is that wonders are yet to come." He claimed that observers in the East were convinced "Seattle is a remarkable place" and "something remarkable is sure to occur here." Relentlessly upbeat in tone, Brainerd's writing, like most booster literature, was given to hyperbole: "everybody in the East says Seattle is an extraordinary place." [12]

A subscription to a clippings service helped Brainerd keep track of his efforts as well as those of competing cities. Always vigilant, when he encountered a negative or misinformed article, he wrote to the editors, demanding a retraction. [13] Often Brainerd's letters employed a deceptively innocent tone, as though the publicity for his city had erupted spontaneously, and was not the result of his calculated efforts. "Seattle is not advertising the Klondike," he argued in one letter-to-the-editor. "The Klondike is advertising Seattle, and we are taking advantage of the Klondike excitement to let the world know about Seattle." [14]

Also effective was Brainerd's correspondence campaign, which employed tactics similar to those of modern political lobbyists. He sent a confidential letter to employers, organizational leaders, ministers, and teachers, encouraging them to ask the large numbers of people with whom they came in contact to write letters about Seattle to out-of-town friends and newspapers. The more spontaneous these letters could appear, the greater their impact. Brainerd thus generated what looked like a groundswell of unsolicited support. The Bureau of Information offered to furnish the details about Seattle as well as the postage to those who agreed to write letters. [15] "It is very important," Brainerd explained, "that Seattle should be first to catch the eye of the reading public and of the intending Klondiker." [16]

Another masterful public relations effort was the production of circulars that promoted Seattle as the gateway to the Klondike. Brainerd designed and wrote one of these to look like an official government publication -- and he convinced Will D. Jenkins, Washington's Secretary of State, to sign it. The circular reassured gold seekers of the safety of the trip to the Yukon, "making it sound like no more than an invigorating outing." The publication also cautioned that no person should embark on the journey with less than $500. [17] A number of European countries -- including France, Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland -- found the circular so appealing that they reprinted it and had it distributed. Encouraged by this success, Brainerd sent pictures and information about Seattle and the Klondike as Christmas presents to the heads of European nations. When Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany refused the gift, fearing it was a bomb, Brainerd used his distrust to gain further publicity. [18]

The Bureau of Information sent additional circulars to every governor and mayor in the United States. These included a series of questions about prospective gold seekers and where they planned to be outfitted. Ostensibly, the purpose of the information acquired was to help Seattle businesses prepare for the stampede of prospectors. The circulars served to advertise Seattle, however, and most recipients turned them over to local newspapers, which printed them. Also, Brainerd provided the information he received from the circulars to Seattle's merchants. [19]

Brainerd's questions elicited some humorous responses. An official of the city of Plymouth, Connecticut, for instance, informed the Bureau of Information that "the 'fever' has had but one victim here as far as we can learn. The young man having married since....has recovered. Think there is no danger from this point." [20] Similarly, a Detroit official indicated that he could not answer Brainerd's questions, reporting as follows: "How many women there are who intend to go; where people would secure their outfits if they did go; when they expect to go, I respectfully submit is a matter probably known only to Providence himself, and I doubt that if you could communicate with Providence that he would give you reliable data." [21] Omaha responded with some boosterism of its own: "'Klondike fever' has not reached us nor is it likely to do so. This species of disease is apt to strike Cities where business is stagnated and people have lost their faith in the return of prosperity. In Omaha however prosperity is no longer a prophecy but a grand reality." [22]

One of the most celebrated of Brainerd's publicity schemes was a traveling exhibit of $6,000 of Klondike gold. Although it cost the Bureau of Information only $275, the Great Northern Express Company carried this display all over the nation, providing exposure to thousands of spectators and prospective stampeders. [23]

In March of 1898, the Bureau of Information's charter expired. At that time, the Chamber of Commerce's finance committee reported that $9,546.50 had been collected for the advertising campaign -- and Brainerd had "made the most of every penny." [24] As a result of his efforts, Seattle received five times the advertising exposure as other cities on the West Coast. [25] In early 1898, The Seattle Daily Times reported that Seattle had become the recognized center of Klondike trade. "There is probably no city in the Union today so much talked about as Seattle," the article informed readers, "and there is certainly none toward which more faces are at present turned. From every nook and corner of America and from even the uttermost parts of the earth, a ceaseless, restless throng is moving -- moving toward the land of the midnight sun and precious gold, and moving through its natural gateway -- the far-famed City of Seattle." [26]

For six months, Brainerd had promoted Seattle at a furious pace. By March of 1898, the work had become "wearing." [27] The next month, he took a new job for the Chamber of Commerce: lobbying in Washington, D.C. for an assay office in Seattle, which would convert the prospectors' gold into cash. An assay office in Seattle would provide returning miners with money that they could spend in the city, allowing merchants to prosper from their business not only on their way to the Klondike but also on their return. While Seattle boosters had advocated this measure from the outset of the gold rush, delegations from San Francisco to Philadelphia opposed the idea, fearing a loss of business in their assay offices. Even so, Brainerd's efforts were successful -- and in June of 1898 Congress passed a bill establishing an assay office in Seattle. [28] The government selected a building owned by Thomas Prosch, a prominent city resident. Located at 613 Ninth Avenue, it was a two-story concrete structure featuring a spectacular view of Puget Sound and the busy harbor. [29]

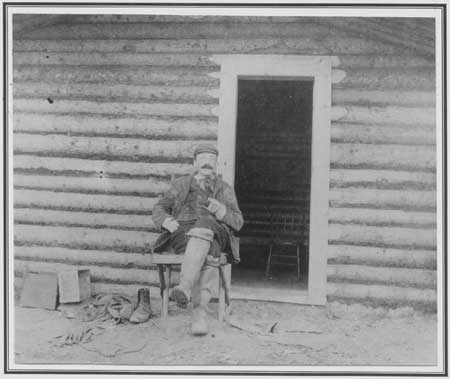

Erastus Brainerd in the Yukon, 1898

(Courtesy Special Collection Division, University of Washington)

The assay office opened in mid-July of 1898 to a long line of miners recently returned from the Klondike. They received money for their "glittering piles," which employees melted into bars and shipped to Philadelphia to be coined. [30] "It was a sight not quickly to be forgotten," noted one observer. "The looks of anxiety depicted upon the faces of those in waiting, the furrows caused by the rough touch of the north wind, and the general unkempt appearance of the miners, told the bystander that these were men who had escaped none of the hardships incident to life in the wilds of the [Far North]." [31] The first day it opened, the assay office took in $1 million in gold, and for the next six months the average receipts totaled one million dollars per month -- far exceeding expectations. [32] By 1902, the assay office had cleared $174 million in gold. [33]

After helping Seattle obtain the assay office in 1898, Brainerd himself headed for the Klondike, perhaps succumbing to his own "gold-rush propaganda." Like many prospectors, Brainerd did not strike it rich in the Far North. He returned to Seattle the following year, becoming involved in numerous professional ventures. He served as "an irrepressible editor" of The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, for instance, from 1904 to 1911. During the early twentieth century, he argued for harbor improvements, public health measures, and civic beautification. He also became vice chairman of the Republican City Committee of Seattle. Given the extent of Brainerd's contributions, his final years seem especially tragic. By 1920, he had become mentally ill -- and the next year he entered Western State Hospital at Steilacoom. He died there on Christmas Day of 1922. [34]

Strangely, Brainerd's obituary in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer mentions very little about the Klondike -- and nothing about his role in promoting Seattle. [35] This omission could suggest that the gold rush represented a minor event in Brainerd's expansive career -- yet later biographers would note that if Brainerd is remembered at all it is for publicizing the link between Seattle and the Far North. [36] It would be difficult to credit Brainerd with single-handedly securing Seattle's place as the outfitting center, since the city's press and business leaders seized the opportunity to advertise weeks before he assumed responsibility for the publicity campaign. Still, Brainerd's efforts to promote the city proved to be enthusiastic and inventive -- even for a booster.

Competition Among Cities

Although it is difficult to evaluate Brainerd's precise impact on the Klondike Gold Rush or on the growth of Seattle, it is certain that the objective of his advertising campaign was reached: Seattle indeed became the gateway to the Klondike. As noted, of the approximately 100,000 prospectors who set out for the Far North, 70,000 selected this city as the place for outfitting and transportation. To some extent, this development was dictated by location. San Francisco and Portland did not enjoy the relative proximity to the gold fields that cities on Puget Sound offered. Meanwhile, smaller cities such as Everett, Bellingham, and Port Townsend did not sustain a population base sufficient to support large-scale businesses that could easily outfit tens of thousands of miners.

Still, the question of why Tacoma did not benefit more from the Klondike trade remains an interesting one, as does the question of why an American city should profit more than Victoria and Vancouver from a gold strike located on Canadian soil. The efforts of Erastus Brainerd help explain how Seattle emerged the victor in the battle for gold-rush business. No other city mounted an advertising campaign that could rival his. Part booster and part huckster, Brainerd was "an optimist and an enthusiast" who had the vision necessary to sell Seattle to the public. [37]

At the outset of the Klondike Gold Rush, it was not clear that Seattle would emerge as the point of departure. Like Seattle, other cities also advertised their merits. It was a measure of Brainerd's success that as the competition for the Yukon trade progressed, other towns agreed on only one thing -- that Seattle was not the place for outfitting and transportation. [38]

Competition Among Cities: San Francisco

Initially, San Francisco seemed to be a formidable rival. The vessel Excelsior had landed there heavy with Klondike gold three days before the Portland docked in Seattle in July of 1897. The Excelsior's berths sold quickly a week later, as the steamer prepared to return to the Far North. [39] The oldest and most populated of the cities vying for the Klondike trade, San Francisco promoted its vast experience outfitting Forty-niners during the California Gold Rush. [40]

Moreover, this city featured significant rail and shipping connections -- and it enjoyed a longstanding link to the industries of the Far North. Before the Klondike Gold Rush, San Francisco served as the gateway city for the Yukon. [41] The Alaska Commercial Company, associated with fur sealing and other activities, was based in San Francisco -- and it was this firm that operated the Excelsior. As the Alaskan Trade Committee pointed out, San Francisco was "many times larger" than other cities on the West Coast -- and its size kept prices competitive. [42] At the time of the Klondike craze, San Francisco had more than 300,000 residents. [43]

Yet San Francisco's advertising campaign was no match for that of Seattle. To be sure, its newspapers publicized the gold strike and the Bay Area's role. As noted, the Examiner hired John Muir to provide observations on the stampede. This naturalist, however, was hardly a booster, viewing the gold rush as "a wild and discouraging mess." [44]

San Francisco also established an Alaska-Klondike Bureau of Information. Staffed with "competent, courteous and painstaking men," the Bureau maintained up-to-date reports on the Yukon, along with an "educational exhibit." It advised prospective miners to travel through San Francisco "because you save time, money and annoyance." Among the more compelling arguments in favor of this city included the number of businesses, which kept prices low and goods in stock, and the ample hotel accommodations. Interestingly, the Bureau also highlighted recreational opportunities, promising that those who traveled to San Francisco would encounter scenery superior to that of northern routes. San Francisco itself, moreover, was "worth seeing." [45]

According to the The Seattle Daily Times, San Francisco merchants organized an advertising campaign in 1897 that emphasized the California city's advantages over Seattle. "The stocks of San Francisco merchants are practically inexhaustible," they claimed, "as against the similar stores of Seattle, which on several occasions....were totally depleted in several lines. Being forced to telegraph to San Francisco for goods, prices were boosted out of sight in Seattle." Not surprisingly, such disparaging claims provoked Seattle promoters, who complained that the California city was "scheming" to take the Yukon trade. [46]

The Seattle Daily Times assured its readers in 1897 that most of San Francisco's Klondike business was local. [47] Located much farther south of the Yukon than the other competing cities, San Francisco encouraged argonauts to take the all-water route. Seattle boosters counteracted this approach by claiming that the trip up the Inside Passage from Puget Sound was safer. [48] The route over Chilkoot Pass to the interior, developed during the 1880s, gave Seattle an advantage over San Francisco. [49] Even so, rail line connections made San Francisco accessible and attractive to prospectors outside California. These included Wyatt Earp, who departed from Yuma, Arizona. "It was hot as Hades," his wife recalled, "and we were fondly remembering cool San Francisco." [50]

For all the early interest in San Francisco, the city did not seriously threaten Seattle's position as the gateway to the Klondike. As Seattle author and historian Archie Satterfield has explained, "somehow the chemistry wasn't right" in San Francisco. [51] The California city did not experience the level of excitement that gripped towns farther north -- and attempts to advertise itself as the point of departure were lukewarm. John Bonner, writing from San Francisco to the national journal Leslie's Weekly, offered a similar explanation in December of 1897. "San Francisco has only just begun to wake up," he pointed out, while Seattle "was the first in the field" to take advantage of the opportunities that the gold rush presented. He characterized Seattle residents as "energetic" and "enterprising" people of the "git-up-and-git kind," who flooded eastern cities with advertising. The people of San Francisco, on the other hand, were "torpid," inclined to "jaw-smithing when they should be acting." [52] In summary, Seattle proved far more aggressive than San Francisco in pursuing the Klondike trade.

Competition Among Cities: Portland

Portland had numerous advantages in the battle for the Klondike trade: a strong, stable financial foundation and extensive rail connections and port facilities. With approximately 60,000 residents, Portland also boasted a higher population than Seattle -- a distinction it retained even after the gold rush. In September of 1897, Portland's business leaders organized an advertising campaign that resembled Brainerd's plan. It included providing maps, pamphlets, and circulars to railroads and prominent eastern publications. W.A. Mears, one of the primary forces behind this campaign, assured fellow businessmen that success in this venture would require extraordinary contributions. "You will have yourself to thank," he warned them, "if you see Seattle go ahead with a bound and distance this city in wealth and population." [53]

The Seattle Chamber of Commerce did not take this threat lightly. As Brainerd explained, "Portland will not do this by halves." Clearly he viewed the city as a rival, asking "Is it likely that Portland with its great aggregated corporate and individual wealth will fail to spend money like water when it thinks that a failure [to do so] will help Seattle?" [54] A large advertisement for Portland appeared in the New York Journal in December of 1897, prompting Brainerd to respond with an advertisement of his own. [55]

The Klondike Gold Rush indeed brought profit to Portland's merchants. From 1896 to 1898, more than 300 new businesses incorporated in Oregon -- and 136 of them were mining-related enterprises. Henry Wemme exemplified a Portland businessman who capitalized on the Klondike stampede by establishing "an immense business in selling tents." [56]

For all this success, however, the Webfoot City, as newspapers called it, did not succeed in wresting much of the business from Seattle. Portland was farther from the gold fields than the Puget Sound cities, and it did not have the frequent shipping service to the Far North that Seattle offered. As a number of historians have pointed out, Portland was established earlier than Seattle, and the older city retained a conservative, complacent character that contrasted with the energy of Seattle promoters. Jonas A. Jonasson, for example, explained in a comparison of Portland in Seattle that "Seattle's favored location on Puget Sound and the vigor of the famous 'Seattle Spirit' that saw its opportunity and took advantage of it was an unbeatable combination." [57]

Competition Among Cities: Tacoma

Tacoma and Seattle had a longstanding rivalry. As the "City of Destiny," Tacoma had won the coveted position as terminus for the Northern Pacific -- the first transcontinental railroad to arrive in Washington. Like Seattle, Tacoma boasted port as well as rail facilities, and it was relatively the same distance from this location to the Klondike. According to historian Murray Morgan, what distinguished Tacoma from Seattle in the race for Klondike trade was its slow pace and lack of vigor. "Before Tacoma awoke to the full possibilities of the rush north," he explained, "Seattle was synonymous with Alaska." Significantly, Charles Mellen, president of the Northern Pacific, arranged for company steamships to leave from commercial docks in Seattle, even though he had to pay rent for those facilities. Ironically, at the outset of the gold rush, the only ship that sailed regularly from Tacoma to the Far North was named The City of Seattle. [58]

Early accounts by the Tacoma press indicated a lack of recognition of the significance of the gold rush. Two days after the Portland arrived in Seattle, The Tacoma Daily News reported that the city "has not gone wild over the Klondike." As the article advised, "It is not well for people to lose their heads over distant gold fields, only to be reached after extreme hardship.... Careful people who are making a living will stay where they are." [59] Initially, Tacoma business responded to the gold rush with "lethargy." [60] While such caution appears prudent in retrospect, it did not help increase Tacoma's share of the Klondike trade.

Similarly, on July 29, The Tacoma Daily News sneered at Seattle's aggressive approach, suggesting that the city "should not make a spectacle of herself." Moreover, the article found "the Seattle spirit" to be "unlovely." While others praised Seattle's "energy and enterprise," Tacoma saw only "hoggishness and snarling." [61] The Tacoma press further pointed out that other Puget Sound cities shared its sentiments. In late July of 1897, The Skagit News-Herald, for example, urged Seattle promoters to "remember this is not yet the harvest time," advising them to proceed more slowly. [62] Tacoma, then, was not alone in failing to recognize the importance of speed in pursuing the Klondike trade.

A few weeks after the gold rush began, Tacoma businessmen began to realize what they were missing. They suggested advertising in eastern newspapers and establishing a bureau of information. "The principal thing for Tacoma to do just now is to advertise," one promoter advised in August of 1897. "Pick up any of the eastern newspapers today and you will find just how much this town is losing by not keeping to the front as a starting and outfitting point for miners bound for Alaska." [63] Another observer in Tacoma noted that "there is the greatest difference in the world between Tacoma and Seattle in this Klondike excitement.... Over there they are all up in arms about it." [64]

The Tacoma City government, however, was not in a position to respond, as it was "bitterly divided" over a mayoral election that had come down to two votes. Because the ballot boxes had been stolen from the city clerk's office, a recount was not possible. As a result, Tacoma was encumbered by two mayors and two civil service commissions. Moreover, the Chamber of Commerce, established in 1884, split three ways when attempting to select a publicity director for a Klondike advertising campaign. [65]

[Source: Erastus Brainerd Scrapbook, University of

Washington]

Accordingly, in late September of 1897, The Seattle Daily Times featured an article titled "Tacoma Has Given Up," suggesting that Seattle promoters did not view Tacoma as a serious threat. It quoted Brainerd as follows: "It is best for the Coast cities to set forth their merits as outfitting points in their own way, and let the intending Klondiker make his own choice. In that case Seattle will stand the best chance to keep and to enlarge the trade she now controls." [66]

By late 1897, Tacoma's Chamber of Commerce had produced a circular titled "Tacoma: Gateway to the Klondike." This publication promoted Tacoma as "the starting point of all steamers for Alaska." Perhaps attempting to avoid inadvertent advertising for rival cities, its authors refused to use the word "Seattle," referring to W.D. Wood as mayor "of one of the Puget Sound cities." [67] The Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade also printed a booklet titled Tacoma Souvenir, which announced that the city "is not the result of an accident," since the Northern Pacific Railroad selected it as the terminus after "exhaustive examinations of the entire northwest." [68]

|

Like boosters in Seattle, Tacoma promoters distributed advertisements to railroads. These billed Tacoma as "the most economical outfitting point for the Klondike." [69] Despite these efforts, however, the Tacoma press revealed that the city remained in a weak position.

Railroads to Tacoma

Attempting to deflect attention from Seattle and the Yukon, The Tacoma Daily News emphasized that there were other "Klondikes" in Washington, where prospectors could strike it rich. This newspaper published a map as part of a special Klondike edition December of 1897 that prominently featured Tacoma as the gateway to the Yukon. Displaying the rail connections that led to the city, it was a direct copy of the map featuring Seattle that the Post-Intelligencer had published in its special Klondike edition two months earlier (see map). Even the organization of The Tacoma Daily News article resembled the earlier Seattle piece. [70]

In summary, Tacoma's efforts to gain the Klondike trade lagged behind that of Seattle every step of the way. When the gold rush ended, according to Morgan, "the race for dominance on Puget Sound was over. Tacoma was the second city. Its struggle in the next years was not for triumph but for survival." During the decade 1890-1900, Seattle's population nearly doubled, reaching 80,676. Tacoma's population increased only 4.7 percent, reaching a total of 37,714. [71] It is interesting to speculate how this outcome might have differed had Erastus Brainerd been named head of the publicity campaign of Tacoma. Even so, it is doubtful that Tacoma, characterized as a "company town" dominated by the railroad, could have surpassed Seattle in the rush for the Klondike trade. [72] Brainerd's enthusiasm and his advertising schemes might not have proven effective without the vision and support of Seattle's business community, which, as noted, immediately seized the opportunity to promote the city.

Competition Among Cities: Additional American Cities

A number of smaller cities on the West Coast attempted to secure some of the Klondike trade. Juneau, for instance, billed itself as "the metropolis of Alaska" and "the gateway to the interior gold fields." Its merchants argued that miners outfitting in their town would reduce or eliminate the cost of transporting freight to the Yukon, and they warned that outfits purchased in Seattle were stowed at the bottom of the ship's hold, where horses and mules stood over them for the duration of the trip to the Far North. [73] Juneau business interests also distributed circulars advertising Juneau on trains that ran between Seattle and Tacoma. [74]

Port Townsend similarly promoted itself as "the principal city on the west side of Puget Sound" and the port entry for the Puget Sound customs district. At the outset of the gold rush, some Port Townsend merchants recognized the need for "prompt interest and vigorous action." Seattle, they noted, had benefited from this approach. [75] "The Seattle papers," one observer pointed out in July of 1897, "are full of advertisements of business houses, giving lists of articles that should be purchased by intending Klondyke gold seekers.... It has been generally believed by them that Seattle was the only place where such goods can be procured." [76]

Port Townsend merchants, along with the Board of Trade, thus launched a relatively modest publicity campaign touting the advantages of their town. Advertisements described Port Townsend as "the principal city on the west side of Puget Sound" and the port entry for the Puget Sound customs district. Steamers bound for the Far North stopped at Port Townsend -- and its businesses offered goods from San Francisco "at the lowest possible rates." Promoters promised that miners who purchased their outfits at Port Townsend would enjoy the advantage of having their goods loaded last on the ship -- since this was the last port stop -- making them the first to be unloaded at the port of discharge in the Far North. The Board of Trade further suggested "that all Eastern parties who come through direct to Port Townsend will be so well pleased that they will all write to their friends to come here as the starting point for the great gold fields of the North." [77]

Without the rail connections that Seattle and Tacoma enjoyed, however, Port Townsend was not positioned to become the "starting point" to the Klondike. Moreover, with a population of only 3,600 residents in 1897, the town did not support the number of businesses that larger cities offered. [78] Although the gold rush renewed the determination of town residents to secure a rail link to Portland, it did not play a major role in the development of the community.

Similarly, Everett and Bellingham, for all their railroad and water connections, boasted fewer than 10,000 residents apiece -- and as historian Alexander Norbert MacDonald has indicated, "their smallness ruled them out as significant competitors." [79] They could not pursue the Klondike trade with the zeal, vigor, and resources that Seattle merchants brought to the enterprise. Newspapers in the Bellingham area, in fact, reported that the Klondike Gold Rush was not what it was "cracked up to be," and advertised placer mines in Whatcom County as rivaling those in the Yukon. [80]

Competition Among Cities: Vancouver and Victoria

Vancouver and Victoria enjoyed an advantage in the scramble for Klondike profits: location. Not only were these cities closer to the gold fields than most West Coast communities but they were Canadian as well. If American stampeders purchased and bonded their outfits in Canada, they were not required to pay an import duty -- and merchants in Vancouver and Victoria made the most of this point in attempting to lure prospectors their way. Business interests in the cities mobilized quickly to mount a publicity campaign that included distributing leaflets and printing articles and advertisements in Vancouver's News-Advertiser and Victoria's The Daily Colonist. These promotions emphasized that the gold fields were located in Canada, and that the British Columbia cities were accessible by rail and steamer. [81] Interestingly, this effort sparked very little friction between the two cities, whose merchants felt the need to cooperate against their American rivals. [82]

(Courtesy Terrence Cole)

Tappan Adney, correspondent for Harper's Weekly, observed a flurry of business activity. "Victoria sells mittens and hats and coats only for Klondike," he wrote. "Flour and bacon, tea and coffee, are sold only for Klondike. Shoes and saddles and boats, shovels and sacks -- everything for Klondike." He reported that some "wide-awake" merchants from Victoria and Vancouver purchased an outfit in Seattle to compare American and Canadian prices. [83]

Despite the responsiveness of Canadian businesses, however, the gold rush had caught the nation unprepared to address confusing trade regulations. For approximately eight months, newspapers in Vancouver, Victoria, and American cities exchanged heated arguments about Canadian customs. Encouraged by U.S. railway officials, Brainerd lobbied Congress to pressure Canada for resolution of the tariff issue. [84] In September of 1897, the Vancouver Board of Trade advertised that all goods purchased in that city "will be certified by the Customs Officers there, and be admitted free of duty, thus saving time, trouble and money to the miner." Seattle newspapers, on the other hand, suggested that no Canadian customs would be collected on goods purchased on American soil. At the outset of the gold rush, duties were seldom collected in the Yukon, since Canada had not yet posted customs officials there. In the fall of 1897, however, Canada established a customs post at Lake Tagish, and by January 1 of the following year, regular duties were established. [85]

In addition to the lack of import duties, Vancouver and Victoria offered accessibility to prospectors. The Canadian Pacific Railway had completed its transcontinental line to British Columbia in 1885 -- and the railroad advertised its services to gold seekers. Vancouver, however, lacked Seattle's trade connections with the Far North. At the outset of the gold rush the Pacific Coast Steamship Company and the North American Transportation and Trading Company, both of which maintained trading posts in the Yukon, were based in Seattle. Vancouver, according to MacDonald, enjoyed no such facilities, and "had to start virtually from scratch in its attempt to capture some of the trade." [86] As noted, the foothold that Seattle had gained in Alaska and the Far North before the gold rush helped the city eclipse the efforts of rivals, including Vancouver.

(Courtesy Terrence Cole)

Moreover, as was the case with other competing cities, Victoria and Vancouver could not match the pace and extent of Seattle's advertising campaign. In 1897, one Canadian publication urged stampeders to exercise caution, noting "there is plenty of time....the gold won't run away. It has been there for several million years already, and will no doubt wait a month or two longer." [87] It is difficult to imagine Brainerd issuing such a statement, which contradicts the spirit of the term "gold rush." Similarly, the Vancouver News-Advertiser cautioned that "only one out of every hundred who risks the venture [to the Klondike] can expect to realize any big results from their hazardous undertaking." [88] In addition to contributing to newspapers, Brainerd published articles in a variety of magazines. Canadian journals, on the other hand, carried few, if any, articles on the gold rush in the fall of 1897. [89] As one historian explained, Canadians were sober, moderate people, not given to the sense of urgency that characterized the American response to the gold strike in the Klondike. Canadians valued "safety and security, order and harmony," whereas "for the Americans who rushed north in 1897 and 1898, [the Klondike] was a last frontier; for them there were no more wilderness worlds to conquer or even to know." [90]

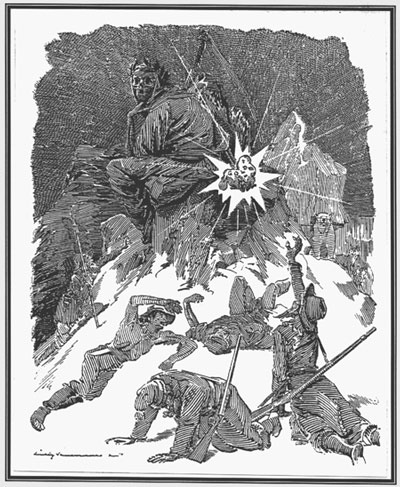

Perhaps it was the British influence that resulted in this conservative, restrained tone. The Illustrated London News portrayed an unappealing side of the gold rush that Seattle newspapers avoided, if not ignored. "Thousands of men are quitting their safe abodes and proved industries or trades," observed one article in 1897, "and making their way, at any cost, with certain loss of what they leave behind." In addition to this dismal assessment of the risks involved in gold seeking, The Illustrated London News described the Yukon as "that remotest and naturally most uninviting north-western corner of the vast British American dominion." [91] Similarly, Punch, a British journal, published a striking cartoon in 1897 that depicted dying miners clawing their way toward a gold nugget, which was guarded by the Angel of Death. [92] Such images were not designed to send gold seekers racing toward Canadian cities for outfitting. In contrast, when Seattle publications depicted the hardships of the Yukon, the narrative typically ended with advice about obtaining sufficient supplies and warm clothing, which could be purchased in Seattle. [93]

Even guidebooks published in Canada touted Seattle -- not Victoria or Vancouver -- as the best place to begin the journey to the gold fields, while The Seattle Post-Intelligencer pronounced the All-Canadian route "worthless." [94] In fact, most American promoters, including Brainerd, downplayed the point that the gold fields were located in Canada -- a tactic that irritated promoters in Victoria and Vancouver. [95] In the end, the Klondike Gold Rush turned out to be primarily an American phenomenon, with as many as 65 percent of the prospectors coming from the United States. [96] Although many miners were immigrants who had recently naturalized, the fact that they started out from the United States might have made them more likely to outfit from an American city. [97]

In summary, although cities such as San Francisco, Portland, Tacoma, Victoria, and Vancouver succeeded in gaining some of the Klondike trade, they were not able to take the majority of it from Seattle, which became the "Queen City" of the Pacific Northwest and the "emporium" of the Far North. [98] None could boast a promoter as effective as Brainerd. Although The Seattle Daily Times expressed concern in 1897 about Seattle's "busy" competitors, fearing "they stop at nothing," it was Seattle's boosters who "stopped at nothing." [99] The Trade Register, a publication produced weekly in Seattle, derided Tacoma in 1897 as "our crotchety, jealous and notoriously unreliable little rival." According to this source, the eastern press "now recognizes Seattle's importance as the leading commercial center and headquarters for the Yukon trade." As The Trade Register further explained, "Seattle is all life and bustle, while Tacoma is as dead as a post." [100]

In addition to its superior efforts at promotion, Seattle had established trade connections to the Far North, as well as railroad and shipping facilities, before the Klondike stampede. Seattle also supported numerous local industries that could activate quickly for the outfitting business. "The gold excitement did not start the wheels going," The Trade Register explained in 1897, "it only gave them a big whirl." [101] The following chapter explores how this "big whirl" affected Seattle businesses.

This striking illustration depicted dying miners clawing

their way toward a gold nugget, guardeb by the Angel of Death. A watchful

bear and a pair of wolves (pictured right) added to the sense of doom.

This cartoon appeared in Punch on August 28, 1897.

End of Chapter Two

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003