|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hard Drive to the Klondike Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush |

|

CHAPTER THREE

Reaping the Profits of the Klondike Trade

"This town of thirty to forty thousand was all Klondike"- Robert B. Medill, Klondike Diary: True Account of the Gold Rush of 1897-1898

"The stores are ablaze with Klondike goods; men pass by robed in queer garments; ... teams of trained dogs, trotting about with sleds; men with packs upon their backs, and a thousand and one things which are of use in the Klondike trade."

- The Seattle Daily Times,1897

An "All-Klondike" Town

Descriptions of Seattle from 1897 and 1898 share a common theme: a sense of energy and purpose had gripped the city. After years of depression, the stampede to the Klondike invigorated the economy, rekindling the Seattle spirit. As was the case with many gold rushes throughout the West, it was generally not the miners who struck it rich. The business district -- centered around what is now Pioneer Square -- flourished, as thousands of gold seekers bound for the Yukon poured into the city, and a variety of merchants stepped forward to meet their needs.

One observer, returning to Seattle after a seven-month absence in the late 1890s, marveled that the sluggish, stagnant town he left bustled with new prosperity. "Up First Avenue and down Second Avenue is one train of fanciful, kaleidoscopic pictures from real life," he wrote. "The stores are ablaze with Klondike goods; men pass by robed in queer garments; ... teams of trained dogs, trotting about with sleds; men with packs upon their backs, and a thousand and one things which are of use for the Klondike trade." [1] Martha Louise Black, a prospector headed for the Yukon, had a similar reaction to Seattle's streets. "Everywhere were piles of outfits," she recalled. These included camp supplies, sleds, carts, and harnesses, together with dogs, horses, cattle, and oxen. [2] The increased commercial activity affected the mood of the city. As one miner summarized, "We found no discouragement in Seattle. This town of thirty to forty thousand was all Klondike." [3]

So profitable was the Klondike trade that during the late 1890s Seattle became the financial center of the Pacific Northwest. [4] By 1900 Seattle's bank clearances -- the amount of money that changed hands in the daily course of the city's commercial life -- had soared more than 400 percent, surpassing those of Portland and Los Angeles. At the turn of the century, only San Francisco enjoyed a greater volume of business among West Coast cities. Seattle bankers attributed this prosperity to the gold rush. [5] The city's merchants, too, remained well aware of the source of their profits. Wa Chong & Company, for example, reported in 1898 that "times are very good.... Klondike gold has helped things very much." [6]

The amount and variety of goods in a typical Klondike grubstake boosted numerous businesses in Seattle. During the winter of 1898, the Northwest Mounted Police required that each miner bring enough provisions to last a year, which could weigh between 1,500 and 2,000 pounds. The "one-ton rule" helped ensure that prospectors would arrive at least somewhat prepared to withstand the difficult environment of the Far North. It also benefited the merchants, who sold the miners this vast quantity of supplies, along with a myriad of services. Approximately 70,000 stampeders passed through Seattle during the Klondike Gold Rush -- each one a potential customer. Some gold seekers invested as much as $1,000 for supplies and transportation. [7]

Not all were men. [8] Although the Seattle Chamber of Commerce discouraged women from traveling to the Yukon, it established a Women's Department, which distributed advice on purchasing an outfit. Moreover, some entire families set out for the Klondike, providing additional opportunities for sales. Articles commonly purchased included groceries, clothing, bedding, sleds, hardware, medicine chests, tents, and harnesses and packsaddles. [9]

Some of the materials marketed to gold seekers were manufactured in the city. The Seattle Woolen Mill, for example, produced blankets and robes "for the Arctic Regions." [10] Another firm made a "special miner's shoe," turning out several dozen pairs per day. [11] Seattle also featured food processing plants, breweries, and foundries that supplied gold seekers. [12] Even so, Seattle merchants obtained many products -- including dry goods and clothing -- from suppliers in New York and Chicago, who shipped their goods west. Sometimes wholesalers in Seattle re-packaged these products under new, Klondike-related brand names. Lilly, Bogardus, and Company, Inc., a Seattle grain and feed dealer, sold products purchased from the Chicago stockyards as "Alaska Dog Feed." [13] By purchasing goods from the East and Midwest, Seattle merchants forged important commercial connections that allowed large stocks to move quickly and efficiently, at reduced costs. [14]

In addition to collecting fees from various merchants to finance its advertising campaign, the Chamber of Commerce gathered testimonials from miners to help Seattle businesses. "I never ate better bacon," one prospector vouched for The Seattle Trading Company. "The flour and beans could not be beat." Moreover, he and his partner did not lose any provisions, indicating that "the packing was first-class." Erastus Brainerd published these testimonials, many of which mentioned specific businesses, in Seattle newspapers. [15]

From the summer of 1897 throughout 1898, the Seattle press was filled with large, illustrated advertisements directed at stampeders. Merchants used the word "Klondike" to sell everything from arctic underwear to insect-proof masks. Crystallized eggs and evaporated foods were heavily advertised. Advertisements promoted an array of ingenious gadgets, including Klondike frost extractors (boilers) and air-tight camp stoves. The smaller "want ads" during this period further demonstrated the range of businesses that used the gold rush to sell their products and services. Vashon College, for example, offered Yukon-bound parents a place to leave their sons and daughters, "while their home is broken up." [16] The connection between the Yukon and what was being sold often appeared tenuous. One business advertised, "Going to the Klondyke? Have your watch repaired." [17] Even clairvoyants used the Klondike craze to sell their services. Flo Marvin, for instance, had predicted the gold strike -- and she frequently advertised her "occult powers," which included locating mines. [18]

Such an array of advertised products made it difficult for gold seekers to distinguish the essential from the useless and cumbersome. Miners had to decide whether to buy an air-tight camp stove, for example, or whether one of Palmer's Portable Houses would prove to be a better investment than a tent. [19] Purchasing agents were available to assist gold seekers in selecting and buying an outfit, but this approach had its drawbacks. Some unscrupulous purchasing agents -- called "cappers" -- took money from naïve miners and bought inexpensive, inadequate food and equipment, pocketing large profits. [20] In any case, some observers reveled in the city's unbridled consumerism during the gold rush. "I like Seattle," William Ballou noted in 1898, "all its different fakirs trying to sell you a gold washer, a K. stove, or a dog team with one lame dog which would get well by tomorrow." [21]

Advertising

During the gold rush businesses on the West Coast used the word "Klondike" to sell everything from opera glasses to evaporated food. The following Web pages include examples of advertising that appeared in newspapers and city directories from San Francicso to Vancouver, British Columbia, during the years 1897-1898.

Sources for theses advertisements include the following: The Seattle Daily Times, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, The Tacoma Daily News, The Morning Leader (Port Townsend), and Vancouver News-Advertiser, 1897-1898.

Equipment and Services

Among the goods advertised were asbestos-lined Yukon stoves, Klondike insect-proof masks, and frost extractors.

Outfits for the Klondike

Some companies offered one-stop shopping by providing complete outfits. Cooper and Levy, one of the most heavily advertised outfitters, warned gold seekers that "you are going to a country where grub is more valuable than gold." This company also ran advertisements showing hapless miners who outfitted with "greenhorns," which left them stranded in the Far North with inadequate provisions.

Transportation to the Klondike

Businesses such as the Alaska Steamship Company advertised "ample room for horses and freight," along with "first-class meals for all."

Clothing for the Klondike

As one advertisement indicated, "The Skagway winds blow hard and cold and reach the bones thro' blankets, woolens and mackinaws." Clothing was an important purchase for Klondike stampeders.

Pharmaceuticals for the Klondike

Medicine cases and drugs were widely advertised during the gold rush. "You will be tired and sore," one advertisement for liniment noted. Another advertisement used humor: "Klondycitis is very prevalent disease which cannot be cured by medical science."

Food

Your life may depend upon your getting the very best grociers," one advertisement warned gold seekers. Evaporated food was heavily advertised, and LaMont's frequently ran advertisements for crystallized eggs, prompting challenges from Hall's a competitor.

Advertising in Tacoma

The longstanding rivalry between Tacoma and Seattle intensified during the Klondike Gold Rush. These advertisements from Tacoma touted the "City of Destiny" as they "best place on Puget Sound." One Tacoma company offered investments in mining "better than Klondike."

Advertising in Canada

Canadian companies advertised "no duty" for Klondike goods purchased in British Columbia.

Newspapers

Newspapers used the Klondike Gold Rush to sell subscriptions. Newspapers also helped link Seattle, Alaska, and the Klondike in the public mind.

Outfitters

Seattle offered numerous companies that could outfit miners -- sometimes in a single stop. Some of the city's retailers captured Klondike trade by marketing complete outfits that included food, equipment, and clothing. The Columbia Grocery Company, Seattle Trading Company, and Fischer Brothers, for example, offered this service. While gold seekers in other cities had to locate and visit a variety of stores, Seattle businesses developed a reputation for providing outfits quickly and efficiently. The Seattle Trading Company, established in 1893, printed special forms listing supplies, and miners could check the items they wished to purchase. [22]

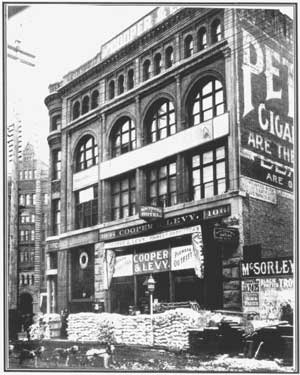

(Courtesy National Park Service)

Cooper and Levy was among the largest and most heavily advertised of the city's outfitters. Isaac Cooper and his wife's brother, Louis Levy, formed a partnership in 1892, providing retail and mail-order groceries, hardware, and woodenware. Their business was located in Seattle's commercial center, at the southeast corner of First Avenue and Yesler (photo, above). During the gold rush, large stacks of goods outside this store became a common sight -- and it remains an enduring image of Seattle street scenes from the period. In 1903, Cooper and Levy sold their business to the Bon Marche. [23]

Schwabacher Brothers and Company was another prominent merchandising business. Established in Seattle in 1869, it was also one of the city's oldest. In 1888, Schwabacher Hardware Company incorporated as a separate business. Schwabacher Brothers and Company sold groceries, clothing, and building materials. The store was located in Seattle's commercial district, and the company also maintained a wharf. These facilities, along with the Schwabachers' longstanding presence in Seattle, placed the company in an advantageous position when the gold rush began. Schwabacher's wharf received considerable publicity in July of 1897, when the Portland, laden with Klondike gold, docked there and set off the rush to the Yukon. [24]

Some Seattle companies that prospered during the stampede continue to serve customers today. These include the Bon Marche, which frequently advertised arctic clothing as well as a mail order business, in Seattle newspapers in 1897 and 1898. Its wares included blankets, shoes, bedding, and general furnishings. Edward Nordhoff, a German immigrant, founded this company, naming it after the famous store in Paris. "Le Bon Marche" translates into "The Good Bargain." During the gold rush, the Bon Marche operated at Second Avenue and Pike Street. [25]

Additional outfitting stores that remained in business a century after the gold rush era included the Clinton C. Filson Company, which operated the Pioneer Alaska Clothing and Blanket Manufacturer, and continues to provide outdoor wear. [26] Similarly, the Bartell Drug Company continues to maintain a chain of stores throughout Puget Sound.

Nordstrom Department Store remains one of the best-known businesses still in operation. John W. Nordstrom, a Swedish immigrant, arrived in the Klondike gold fields in 1897. He struggled there for two years, supporting himself by taking odd jobs. When Nordstrom finally hit pay dirt, another miner challenged his claim, and he sold it. In 1899, he arrived in Seattle with $13,000, which "looked like a lot of money" to him. Two years later Nordstrom invested $4,000 of his newfound wealth in a shoe store, which he opened with his partner, Carl F. Wallin. Located at Fourth Avenue and Pike Street, the business prospered for nearly 30 years -- and Nordstrom and Wallin bought another store on Second Avenue. By the late 1920s, the partnership had soured, and Nordstrom bought Wallin's shares. Nordstrom's sons bought the shoe store during the 1930s, expanding it into a retail business with multiple locations. [27]

Although Nordstrom's was not founded during the stampede of 1897-1898, it benefited from the vigorous economy that the Klondike Gold Rush encouraged in Seattle. Subsequent gold strikes in Alaska at the turn of the century continued the momentum, bringing additional customers to Seattle outfitters as well as other businesses, described below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

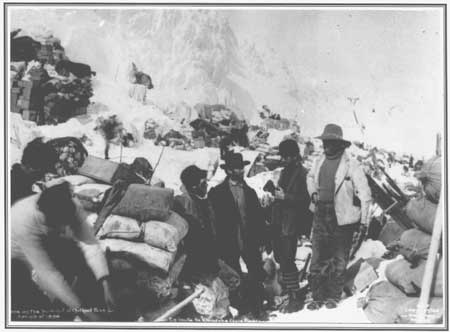

Miners and their supplies enroute to the Klondike gold fields.

(Courtesy Selid-Bassoc Collection, Alaska and Polar Regions Archives,

Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, Fairbanks)

Transportation

Seattle's transportation facilities proved crucial to its success in securing Klondike trade. As noted, at the outset of the gold rush the city already had rail and marine connections in place. Miners could take a train to the city, where they could then obtain passage on a steamship to the Far North.

Stampeders of '98.

(Courtesy Selid-Bassoc Collection, Alaska and Polar Regions Archives,

Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, Fairbanks)

Railroads

Rail links were especially significant. Seattle served as the terminus for the Great Northern Railway, completed in 1893. By the early 1890s, the city had also developed an extensive local railroad network. The Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad (originally the Seattle and Walla Walla), linked the city with the coal fields at Newcastle, Renton, Franklin, and Black Diamond. The Seattle Lake Shore and Eastern transported produce from the east side of Lake Washington to the city, while its northern branch connected Seattle with Snohomish, Skagit, and Whatcom counties. Moreover, Seattle could be reached through spur lines via the Canadian Pacific in Vancouver, British Columbia, and the Union Pacific in Portland, Oregon. In addition to carrying passengers, railroads shipped lumber, coal, fish, and agricultural products from Seattle. [28]

While bringing stampeders to the city, these rail connections also delivered goods to merchants who supplied the miners. Rail shipments in Washington state increased dramatically -- as much as 50 percent per year -- during the late nineteenth century. Seattle became the "central point" of rail traffic, in part due to the "Alaskan trade." [29]

Shipping

By the time of the Klondike Gold Rush, Seattle also functioned as the central point for water traffic of freight and passengers to Alaska. Before the 1890s, San Francisco controlled trade with the Far North. During that decade, however, Seattle merchants gained a strong foothold. In 1892, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company of San Francisco shifted its center of operations from Portland to Seattle, which was closer and could offer an ample supply of coal. [30] As noted, the Alaska Steamship Company formed in Seattle in the mid-1890s -- and the North American Transportation and Trading Company also operated there. [31]

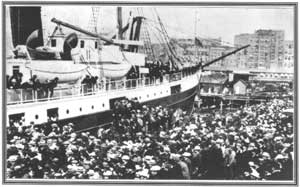

Gold seekers in Seattle board the Portland, bound for the

Klondike.

(Courtesy National Park Service)

The Klondike stampede boosted Seattle's shipping to the Far North considerably. According to a newspaper report, Seattle's fleet tripled in size between 1897 and 1898, in part due to the "Alaskan business." [32] So pressing was the demand for steamships in the late 1890s that some vessels of marginal quality were placed in service. Seattle's shipping "never was so entirely engaged," explained one reporter in 1897. "Not a single vessel seaworthy and capable of use" was overlooked. [33]

During the late nineteenth century, shippers filled these vessels to capacity. The Alaska Steamship Company, for instance, operated vessels that carried as many as 700 passengers apiece. In general, each ship ran between Seattle and the Far North one and one-half times per month. [34] To prospector Martha Louise Black, it seemed that steamships left Seattle for Alaska "almost every hour." [35] The historian Clarence B. Bagley noted that all this activity resulted in a "scene of confusion" on the Seattle waterfront that "has never been equaled by any other American port." The docks were piled high with outfits, and crowds of impatient miners "anxiously sought for some floating carrier to take them to the land of gold." [36]

Shipping continued to expand in Seattle during the subsequent gold rush to Nome in 1899-1900. By that time, according to Bagley, the city's fleet had become a "great armada." He detected an interesting trend: at the end of the nineteenth century, only 10 percent of the ships sailing from Seattle to Alaska were owned and operated by people based in Seattle. In 1905, however, more than 90 percent of the vessels sailing from Seattle to Alaska were controlled by Seattle residents and businesses based in the city. [37]

Shipbuilding

The increase in shipping stimulated the boatbuilding industry during this era. At the end of the nineteenth century, many shipbuilders in Seattle tripled their output as well as their number of employees. [38] Prior to this point, most ships constructed in the city included small fishing vessels or boats for local trade. During the decade 1880 to 1890, Seattle shipbuilders produced approximately 75 vessels, the average weight of each totaling 33 tons. In 1898, Seattle shipyards built 57 steamers, 17 steam barges and scows, and 13 tugs. [39] Wood Brothers of West Seattle constructed and launched the first steamer built "wholly for Yukon trade." This vessel measured 75 feet long and 20 feet wide. [40] Moran Brothers Shipbuilding Company produced many of the vessels constructed during the gold rush era. In early August of 1897, the North American Transportation and Trading Company ordered a fleet of 15 ships from this business. "A stroll through the extensive works of Moran Bros. discloses a varitable [sic] hive of industry," observed one reporter. "About 400 men are employed and separate forces are at work day and night." The "immediate cause" of this activity was the Alaska trade. [41] Gold strikes in western Alaska at the turn of the nineteenth century -- which required ocean-going vessels that could sail the Bering Sea -- further stimulated the shipbuilding industry in Seattle. [42]

Animals for the Yukon

In addition to encouraging the development of rail and marine transportation in Seattle, the Klondike Gold Rush also fostered businesses that assisted miners in getting around once they arrived in the Yukon. The stampede increased the market for dogs, horses, goats, and oxen -- all of which moved people and supplies to the gold fields.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, Washington State

Historical Society)

Dogs became the most heavily publicized animals for sale. The use of these animals in the Far North dated back centuries. By the turn of the century, Tappan Adney, a correspondent for Harper's Weekly, had observed an "extraordinary demand" for dogs to carry sleds and saddlebags. Yukon miners had "raked and scraped" the Canadian Northwest in search of dogs, resulting in a shortage. [43] A single dog could draw 200 pounds on a sled, and six of these animals could carry a year's worth of supplies for a miner. [44]

Adney described a variety of breeds, including Eskimo, husky, malamute, and siwash. So similar were these dogs in physical appearance that he had difficulty distinguishing them. He did, however, detect differences in characteristics among the various animals. The Eskimo dog, for instance, featured a "wolf-like muzzle," but lacked the "wild wolf's hard, sinister expression." The malamute, on the other hand, was a dog "without moral sense," often approaching "the lowest depths of turpitude." [45] The Klondike trade in canines was not limited to these large animals; Seattle dealers also sold "little dogs not much larger than pugs." [46]

The scarcity of dogs made sale of these animals a lucrative business. Miners, according to Adney, were "willing to pay almost any price," and dogs brought "fabulous" sums in the Yukon during the winter of 1897-1898. The best dogs sold for $300-400 apiece. By the summer of 1898, approximately 5,000 dogs had arrived at Dawson City, indicating the size of the market. [47] Teams of dogs waiting for transport remained a common sight throughout the commercial district in Seattle during the gold rush. [48]

Businesses such as the Seattle-Yukon Dog Company imported "all kinds of canines" from as far away as Chicago and St. Paul. In addition to transporting the animals, the company trained them in preparation for their service in the Yukon. "Dog drivers" placed the animals two at a time in a harness attached to a sled, compelling them to pull it for half an hour. "At first it is hard work," noted one observer, "but nearly all of the dogs soon understand what is wanted and pull the sled without trouble." [49] As Adney pointed out, however, not all dogs that reached the Yukon were trained. [50]

The vast number of dogs brought into Seattle for the Klondike trade created problems for merchants as well as for the animals. Some dog yards held as many as 400 animals at once -- all waiting to be shipped to the Yukon. One November morning in 1897, 200 canines, held together in a single yard, engaged in "one big dog fight." The noise was "deafening," prompting The Seattle Daily Times to dispatch a reporter to investigate the event. He described the animals as "snarling, biting, fighting canines who were doing their best to annihilate each other." Not surprisingly, nearly every dog was wounded in the brawl. [51]

The Klondike stampede also created a demand for horses. A Yukon horse market operated on Second Avenue and Yesler -- and the commercial district also offered horses "at every corner" for $10 to $25. By early October of 1897, within three months of the onset of the gold rush, 5,000 horses had been shipped to the Far North from Seattle. Encouraged by the volume of sales, one Seattle firm ordered 4,000 burros from the Southwest. Merchants selling tack and horseshoes also benefited from the trade. Many of these animals died, however, killed by exposure, lack of food, and overwork. Their carcasses littered the trails to the gold fields, serving as a grim reminder of the consequences of hasty marketing and ignorance of northern conditions. [52] Even so, the trade in horses, burros, and dogs remained active, prompting the Seattle newspapers to carry a special section devoted to this topic in the want ads.

Gold seekers not inclined to buy dogs, horses, or burros had another choice: goats. While merchants advertised dogs as faithful, hard-working animals, businesses trading in goats pointed out that their animals were less expensive to purchase and maintain -- and they could furnish milk, butter, food, and clothing. [53] Goats, they argued, also proved to be sure-footed on steep, icy inclines, and they could "gather their feed on the trail." [54] Miners also purchased oxen in Seattle, which they shipped to the gold fields. [55]

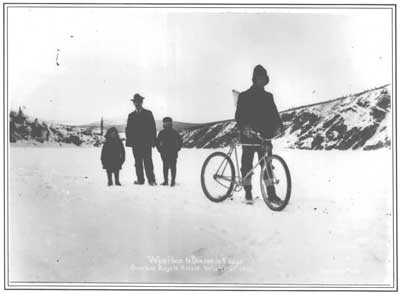

Wheels on Ice

(Courtesy Terrence Cole)

One of the most colorful, whimsical means of getting around the Yukon was by bicycle -- and Seattle merchants advertised them during the stampede. [56] The gold rush coincided with the worldwide bicycle craze of the 1890s, when riding "wheels" became a fashionable pastime. One New York Company considered producing a "Klondike Bicycle," which representatives claimed could carry gold seekers across Chilkoot Pass to Dawson City. For all the impracticality of that particular idea, numerous miners brought bikes to Alaska -- and they were available for purchase in Seattle. Spelger & Hurlbut, dealers operating on Second Avenue, sold bicycles that they obtained from the Western Wheel Works factory in Chicago. By 1900, one Seattle newspaper had reported that "scarcely a steamer leaves for the North that does not carry bicycles." [57]

This mode of transportation offered several advantages: cyclists could follow the tracks in the snow left by dogsleds with relative ease; they could travel faster than dog teams and horses; and "iron steeds" were less expensive and easier to maintain than animals. Cycling in the Far North was not without hazards, which included snowblindness and eyestrain from attempting to follow a narrow track through the ice, and frequent breakdowns due to frozen bearings and stiff tires. [58]

White Horse to Dawson in 5 Days

Overland Bicycle

Record, Winter of 1903

(Courtesy Selid-Bassoc Collection, Alaska

and Polar Regions Archives,

Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska,

Fairbanks)

"A Hot Town" and "A Very Wicked City"

By day, Seattle bustled with activities associated with outfitting and transportation. By night, according to one newspaper headline, it became "A Hot Town" that catered to the needs of a largely transient population. The influx of people during the Klondike stampede included dock workers, ship crews, and various merchants, as well as miners -- most of whom were passing through. They increased the demand for accommodations, food and drink, entertainment, and other services. "The town is overrun with strangers," marveled one observer, "the hotels are crowded; the restaurants are jammed;" and "a number of theaters are running full blast." [60] The large number of people pouring into the city created a need for hotels, rooming houses, and other service industries. [61] As a result, downtown Seattle was a lively place -- "a great carnival of the senses" -- at all hours. [62]

The hotel business thrived in Seattle during the gold rush. Accommodations at the high end included the Hotel Seattle (originally the Occidental) at First Avenue and Yesler, the Butler Hotel at Second Avenue and James, and the Grand Pacific and Northern hotels on First Avenue. These were elegant buildings that offered a variety of amenities, including suites and dining rooms. [63] Less expensive rooming houses were also available throughout the commercial district. These featured small units arranged along a narrow corridor, providing very little privacy. [64]

The Hotel Seattle.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division,

University of Washington)

The supply of rooms, however, could not always meet the demand. "More Klondykers than ever were in town last night," noted one newspaper article from August of 1897. "For the first time since the fire men were walking the streets in the lower part of the city unable to get a bed, although they had money in plenty. The parlors in many of the hotels were filled with cots." [65]

In addition to searching for accommodations, a "great number" of people spent their evenings "out doing the town." Much of their activity centered around the Tenderloin -- an area bordered by Yesler Way, Jackson Street, Railroad Avenue, and Fifth Avenue. Here, gold seekers could enjoy "all kinds" of activities, not all of which were legal. [66] So lively was this district that in the fall of 1897 Seattle's City Council increased the size of the police force by approximately 40 percent. The town grew 500 percent "in rogues and rascals," one newspaper article explained. [67] Robberies and assaults became especially common crimes in this area. By November of 1897, Seattle had become "the greatest petty larceny town on the Coast." [68] As one reporter summarized, it is "a very wicked city just now." [69]

The excitement in the Tenderloin was encouraged by the sales of alcohol and the openings of numerous saloons. New drinking establishments in 1897 included the Torino and People's Café on Second Avenue South, and the Dawson Saloon on Washington Street. Typically, these businesses served beer, whiskey, and even champagne. They attracted "the Klondikers going and coming, for the majority of them get drunk at both stages of the game." [70] One visitor claimed that Seattle boasted one saloon for every 50 citizens, and he published these observations in The New York Times. Accordingly, the Tenderloin acquired a reputation like that of the Barbary Coast in San Francisco. [71]

Seattle newspapers were filled with stories illustrating the consequences of widespread drinking. In August of 1897, one gold seeker reported to city police that he had been robbed of $300 while "doing" Washington Street during the evening. The police could locate no suspects. Just as they were about to give up the search, the man sheepishly informed the authorities that he had apparently deposited the missing $300 at his hotel while intoxicated -- an act of good sense that he could not remember. [72]

Captain Bensely Collenette of Boston was not so fortunate. He had come to Seattle to lead a party of miners to the Yukon. Upon arriving in the city, he "went on a glorious drunk," spending "his money like wind." On Washington Street, he was robbed of $185. Even so, Collenette was later observed "riding around the city in the finest hack in town," and he left for the Yukon on the steamer Cleveland. [73]

Along with the problems that alcohol presented, the police contended with morphine and opium "fiends" in the Tenderloin. Many drug stores sold these substances, often remaining open at night for that purpose. Newspapers credited morphine and opium with murder, robbery, and leading women to a "life of shame." [74]

During the late nineteenth century, Seattle featured a variety of brothels, including the Klondike House. Located on the corner of Main Street and Second Avenue South, this establishment functioned as the "stopping place for the worst of Seattle's fallen women," and it gained the reputation of being one of the "worst dives in the city." [75] Newspaper reports of the Tenderloin focused on prostitutes -- known as "soiled doves." Prostitution had existed in the city long before the late 1890s, but the gold rush increased its visibility. Women also worked as comediennes, singers, dancers, and actors in the district's theaters -- and they dealt cards in the gambling houses that sprang up during the gold rush. [76]

Gambling was a lucrative business that caught gold seekers before and after their trip to the Klondike. By the turn of the century, the Standard Gambling House, for example, had averaged more than $120,000 per year. [77] In addition to card games, customers could try their luck with the "Klondike dice game." [78]

In summary, vice became a prominent industry in Seattle during the stampede -- one that attracted as much immediate attention as outfitting and transporting miners. Newspapers focused on this topic from 1897 through 1910 -- in part because sensational and scandalous stories increased sales. The Seattle Daily Times condemned Mayor J. Thomas Humes for his failure to suppress gambling and other "social evils" in Seattle, likening his supporters to an army of "besotted drunks." In 1902, voters approved a reform measure that controlled vice through saloon license fees of $1,000 and evening and Sunday closings. [79]

The excesses of the Tenderloin during the Klondike stampede link the gold seekers to other figures in western history. During the early nineteenth century, mountain men and trappers emerged once a year from the remote, far-flung areas where they hunted beaver. They met at a rendezvous -- a caravan that purchased their beaver pelts and sold them supplies. After transacting their business, many trappers drank and gambled away their annual earnings, turning the rendezvous into a "scene of roaring debauchery." The caravan's owners, on the other hand, profited handsomely from this arrangement, often enjoying returns that reached 2,000 percent. [80] For the most part, those who made fortunes from the fur trade, like those who reaped profits from the gold rush, were not the people directly involved in extracting the resource; they were the ones that sold the goods and services.

|

Labor Employed in Seattle Factories, 1900

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Occupation of Seattle Work Force

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Population and Economic Growth During the Gold-Rush Era

It was during the late 1890s that Seattle eclipsed other Puget Sound communities as the state's most populous city. By 1890, Tacoma's population had reached 36,006 -- which was fairly close to Seattle's 42,837 residents. During the decade of the 1890s, however, Tacoma gained only 1,708 residents, while Seattle's population rose by 37,834, to a total of 80,671. [81]

Most of this growth -- approximately two-thirds -- occurred between 1897 and 1900, when the city increased from 56,842 to 80,671. [82] This development suggests the influence of the Klondike Gold Rush. By 1910, Seattle had developed into a city of 237,194 residents. Seattle's growth exceeded that of many other comparable cities in other regions of the country during this period.

|

Growth of Selected American Cities

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For all this dramatic growth, the ethnic composition of Seattle's population did not change appreciably during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1880, native-born whites comprised approximately 69 percent of the population, while in 1910 they accounted for 70 percent. The percentage of foreign-born whites also remained stable, at around 26-27 percent. Between 1890 and 1910, African-Americans made up one percent of the city's population, while Asians comprised around 3 percent. [83]

Most native-born residents in Seattle came from somewhere else -- particularly the Midwest and East Coast. In 1910 only 16 percent of the city's residents were from Washington. Seattle's foreign-born population was comprised of migrants from Canada, Sweden, Norway, Great Britain, and Germany in 1880. Immigration from Japan, Italy, and Russia had become more common by 1910. [84]

Rapid population growth could be viewed as an indication of economic prosperity. Seattle's population figures reveal that the late 1890s and early twentieth century -- the era of the Klondike stampede -- was a period of vigorous expansion. [85] Even so, an examination of population figures for other western cities during the 1890s demonstrates comparable growth. Although Portland and Vancouver, British Columbia, did not attract the Klondike trade to the extent that Seattle enjoyed, they both expanded at a faster rate than Seattle, perhaps due to momentum gained early in the decade, before the gold strike. This trend suggests that the continuing movement west of the population of the two nations proved to be a significant influence on growth. [86]

|

Population Composition of Selected American Cities

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By 1910, Seattle's position as the state's commercial center was assured. The region's rail and water transportation network also concentrated in the city. Foreign trade grew during the early twentieth century as well, shifting from British Columbia to Asia. On the surface, Seattle's manufacturing base seemed sound, as the city produced an array of products ranging from shoes to beer to bicycles. Yet, according to historian Alexander Norbert MacDonald, Seattle continued to rely mostly on extractive industries, including lumbering, fishing, and agriculture. Although the gold rush helped ensure Seattle's position as a commercial center for the region, it did not provide a broad, diversified manufacturing base that could rival the industrial cities of the eastern seaboard. [87]

|

Composition of Seattle's Population

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition

In May of 1898, The New York Times announced that the Klondike excitement was "fizzling out." [88] Although this assertion proved to be premature, it signaled that the frenetic pace of the stampede was slowing down and that the media's interest was waning. The outbreak of the Spanish American War in April provided a new arena for the nation's reporters, and that topic pushed the Klondike out of the headlines. [89] By late 1898, the rush to the Klondike had subsided considerably. The following year new gold discoveries in Nome deflected attention from the Yukon to western Alaska, and Seattle continued to function as an outfitting center. [90] In April and May of 1900, approximately 8,000 gold seekers passed through Seattle on their way to Nome. [91] During the early twentieth century, miners continued to travel through Seattle on their way to subsequent gold rushes to Fairbanks, Kantishna, Iditarod, Ruby, Chisana, and Livengood. [92]

The trade to the Far North never regained the excitement of the Klondike Gold Rush. Seattle, however, retained its dominant connection to this region -- and it continued to supply Alaska with lumber, coal, food, clothing, and other goods. By 1900, Alaska's population had reached 63,592 residents, many of whom remained "heavily dependent" on Seattle for trade. [93] This link between Seattle and the Far North endured throughout the twentieth century.

To celebrate its ties to the Far North and to commemorate the Klondike Gold Rush, Seattle hosted the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909. This world's fair represented a "coming-of-age party" for the city, signaling the end of its pioneer era. In 1905, Portland similarly hosted the Lewis and Clark Exposition to commemorate the centennial of the 1805 expedition to the Pacific. Its fair attracted three million visitors -- a point Seattle boosters noted with interest. Four years later, Seattle's exposition drew nearly four million people, focusing national attention on the city and the region. [94]

Organizers wanted to hold the event in 1907, to honor the 10-year anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush. Jamestown, Virginia, however, also planned to celebration its 300-year anniversary with a fair in 1907. In any case, the Panic of 1907, a nationwide depression that slowed the economy in Seattle, would have reduced the scale of festivities and the visitation -- so it was a fortuitous turn of events that delayed the exposition until June of 1909. [95] On that date, President William H. Taft at the national capitol pressed the gold nugget Alaska key, setting the fair's operations in motion. Railroad magnate James J. Hill greeted 80,000 spectators in the commencement celebration, which included a parade in downtown Seattle. [96]

The Olmsted Brothers served as landscape architects of the fair, while John Galen Howard became its principal architect. Held on the grounds of the University of Washington campus, the exposition featured pools, fountains, gardens, and statuary that opened on a vista of Mount Rainier. A variety of ornate buildings designed in the French Renaissance style housed exhibits from all over the world. [97]

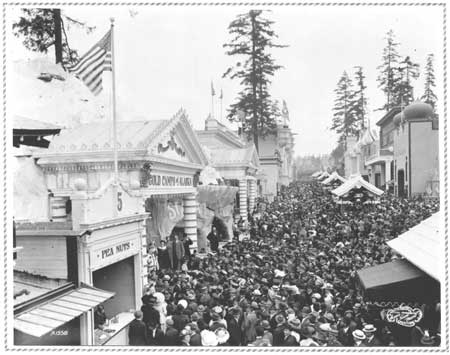

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition included an amusement park

called the "Paystreak;" a term for the richest deposit of gold in placer mining.

The Paystreak featured an attraction called "Gold Camps of Alaska."

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

The exposition included an amusement park with carnival rides and other entertainment. It was called the "Paystreak" -- a term for the richest deposit of gold in a placer claim and an allusion to the importance of gold mining to Seattle. The Paystreak featured an attraction called "Gold Camps of Alaska" as well as an Eskimo village. Additional references to the Far North at the exposition included a large gold nugget, on display from the Yukon. Especially visible was the Alaska monument, a column measuring 80 feet high. Covered in pieces of gold from Alaska and the Yukon, it stood in front of the U.S. Government Building, reminding visitors of the ties between Seattle and the Far North. [98]

While reflecting on the past, the exposition also looked to the future -- and organizers hoped to boost interest in Seattle and the Northwest. "This summer's show is essentially a bid to settlers," noted one reporter, "and an advertisement for Eastern capital to come West and help develop the natural resources which offer wealth on every hand." The exposition featured numerous promotional booths from cities such as Tacoma and Yakima. Washington and other western states financed construction of buildings that featured their products and resources. The exposition also celebrated the Pacific Rim, promoting increased trade with Asia. Japan, China, Hawaii, and the Philippines provided exhibits, and a Japanese battleship docked in Seattle's port in honor of the fair. [99]

Seattle merchants and residents hoped that the economy would boom as a result of the Alaska-Yukon Exposition. Irene and Zacharias Woodson, for example, expected the demand for housing to expand in the summer of 1909. This African-American couple operated a cigar store and rooming houses in downtown Seattle, using the profits to purchase new properties. The Woodson Apartments, constructed in 1908 at 1820 24th Avenue, represented these hopes. [100]

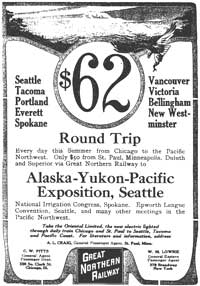

The exposition ended in October of 1909, marking the end of an era. Although most of the infrastructure was removed, several buildings remained, including Cunningham and Architecture halls. Today, they stand on the University of Washington campus as testaments to a significant point in Seattle's history.

The Great Northern Railway advertised the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific

Exposition.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

Another legacy of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was that it strengthened the link between Seattle and the Far North in the public mind. Seattle had developed a significant connection to Alaska before the Klondike Gold Rush, and promoters such as Erastus Brainerd had used the stampede as an occasion to publicize that tie in the late 1890s. The exposition similarly advertised it in 1909. As historian Clarence B. Bagley summarized, the fair successfully met the city's objectives: it demonstrated "the enormous value of Alaska to the United States and the greatness of its entry port, Seattle. The city's guests left the fair with the knowledge that Alaska was a golden possession and Seattle a growing metropolis." [101]

It is difficult to measure the precise impact of the fair and the worldwide exposure it provided to Seattle. As noted, by 1910, the city's population had jumped to 237,194 residents. According to MacDonald, however, the dramatic growth in the city's economy occurred before 1910. After that point, the city "settled down to the moderate growth of the region," abandoning the "independent, enthusiastic" mood of the previous era. [102] Seattle's foreign trade had grown rapidly during the first decade of the twentieth century, but for all the hopes of exposition promoters, there was no immediate increase in trade with Asia after the fair. [103] Not until the late twentieth century would Seattle again experience the vibrance and energy exhibited during the gold-rush era.

Post Cards from the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

(Courtesy Office of Urban Conservation, Seattle)

End of Chapter Three

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003