|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Hard Drive to the Klondike Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush |

|

CHAPTER FOUR

Building the City

"Seattle is the result of a patriotic, unselfish, urban spirit which has been willing to sacrifice in order to gain a desired end -- the upbuilding of a great city....Seattle has well-paved streets, a thorough and satisfactory street car system, large and handsome business blocks, and residence districts adorned by palatial homes and green and velvety lawns."- Daniel L. Pratt, "Seattle, The Queen City,"

The Pacific Monthly, 1905

Seattle changed more during the gold-rush era than in any other period in its history. The rapid economic and population growth of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries spurred the development of the city's infrastructure, transforming it from a town to a metropolis. As one historian observed, if Rip Van Winkle had appeared in 1883 after a 30-year absence, he would have easily recognized what he saw: a town dependent on the lumber industry and water transportation. Similarly, if he awakened in the 1940s after a 30-year absence, he would find the city bigger but not fundamentally changed. However, if he fell asleep in 1880 and returned in 1910, he would not have known where he was. Although natural landmarks such as Mount Rainer and Puget Sound remained in their familiar positions, "Seattle had undergone more profound changes during these thirty years than in any other thirty year period." [1] An examination of the city's infrastructure reveals the extent of these changes.

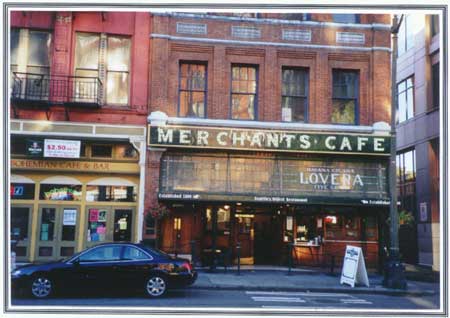

Established in 1890, the Merchants Cafe, located at Yesler and

Marion, advertises itself as Seattle's oldest restaurant.

It operated during the Klondike Gold Rush.

(HRA photo)

Buildings

During the gold-rush era, building along the waterfront increased dramatically. Schwabacher's rebuilt and extended its wharf. The Northern Pacific Railway extended its Yesler dock, and the Great Northern Railway added a new facility that included docks, warehouses, and a wheat elevator. [2]

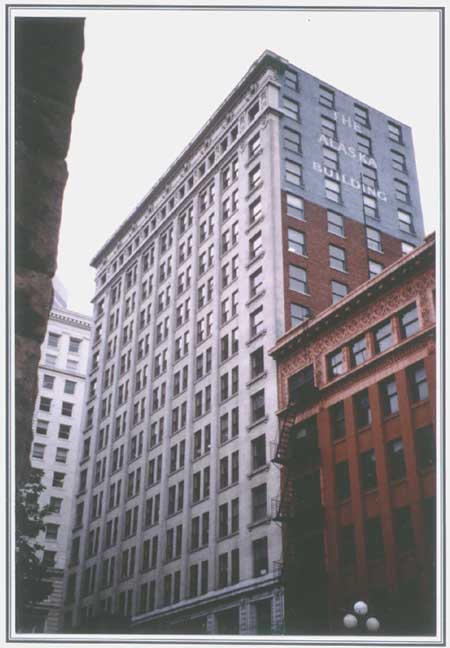

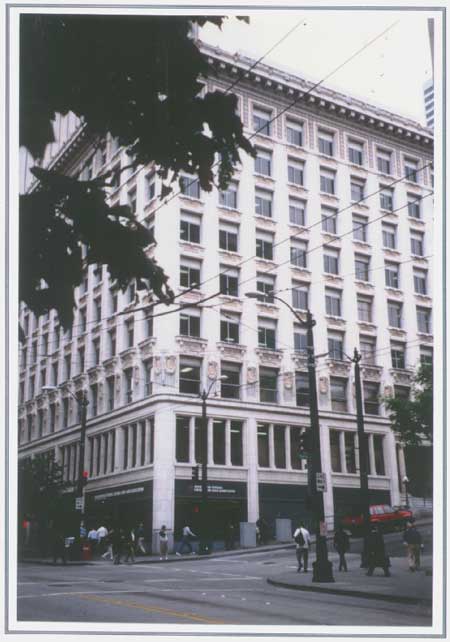

The changes within the commercial district were especially visible. As noted, brick and masonry buildings replaced wooden structures after the fire in 1889. Building in the downtown area became denser, and the size and scale of structures increased. The Alaska Building, the city's first steel-frame skyscraper, appeared in 1904. Located at Second and Cherry, this 14-story structure symbolized the significance of the gold rush to Seattle. The porthole windows along the top floor looked out over the waterfront, providing a view of the shipbuilding, shipping, and rail industries that the gold rush encouraged. For many years a gold nugget embedded in the front door of this building reminded visitors of the stampede and the city's connection to the Far North. Construction of the Arctic Building at Third and Cherry in 1914 similarly represented Seattle's connection to Alaska. This stately structure was noteworthy for its Italianate terra-cotta façade, tusked walrus heads, and rococo-gilt Dome Room. [3]

(HRA photo) |

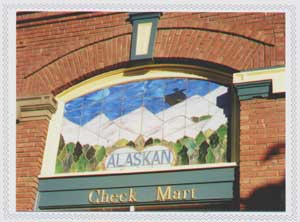

The Alaskan window (pictured right) appears on the first floor of the Morrison Hotel, located at 501 Third Avenue. This building, constructed in 1908, was the original home of the Arctic Club, comprised of the city's leaders and entrepreneurs.

That year, the Arctic Club merged with the Alaska Club, a commercial organization of Alaskans in Seattle. For years, the Alaska Club had maintained a reading room featuring Alaska newspapers and mineral exhibits, and its leaders promoted the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. In 1916, the Arctic Club moved to the Arctic Building.

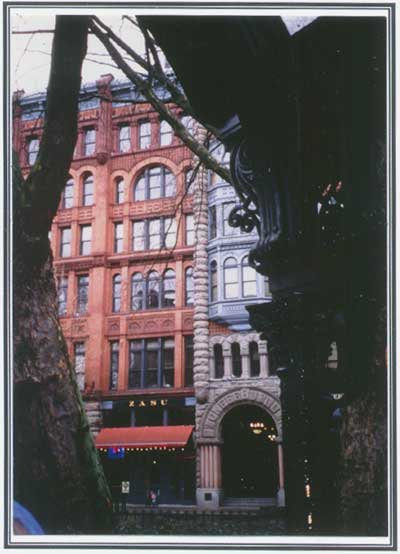

Prominent architect Elmer Fisher designed the Pioneer Building,

pictured below. Constructed in 1889-90, this building reflected the optimism

of the developing city after the fire. This Victorian structure is embellished

with Romanesque Revival features, including rusticated stone columns extending

above the building's central entrance. This striking building was located

in the heart of the city's commercial center during the Klondike Gold Rush.

(HRA photo)

Alaska Building

Seattle's connection with the Far North is reflected in a

variety of structures, including the Alaska Building (pictured above),

located at Second and Cherry, and the Arctic Building,

located at Third and Cherry.

(HRA photo)

Arctic Building

Arctic Building, constructed in 1914.

(HRA photo)

Twenty-seven walruses ring the third-floor exterior of the Arctic

Building.

(HRA photo)

Street and Transportation Improvements

The influx of people during the late nineteenth century increased the need to provide access to the city's commercial district, requiring street improvements within the downtown area. During the 1880s, many streets had been covered with wood planking. This material had its drawbacks: it did not last long and engineers feared it was unsanitary. By the early 1890s, gravel was used to pave some Seattle roads, but hauling the quantities required proved expensive and difficult. By that time, brick had become another favored material. [4]

In 1898, engineers at Smart and Company leveled First Avenue from Pine Street to Denny Way, using the earth to fill Western and Railroad avenues, located along the waterfront. [5] That year, the city also laid new planking and paving from First Avenue to Fourth Avenue, between Yesler Way and Pine Street. One article in The Seattle Daily Times cited 1898 as a record-breaking year for improvements, noting that contractors "flourished as they have not done before." [6]

Streetcars also facilitated movement in the downtown area. The first street railway appeared in 1884, offering nickel-a-fare service. Operated by the Seattle Street Railway Company, it used horses to pull the cars. Five years later an electric streetcar began operating in Seattle -- and even the fire did not interrupt its service. During the 1880s, Seattle's downtown area also featured a cable railway, which ran along Yesler Way and First and Second avenues. By the early 1890s, passengers could travel to Lake Union along Westlake Avenue and to points farther north. [7] Promoters praised these developments, noting how they had transformed the city during the gold-rush era. An article in The Pacific Monthly, published in 1905, informed readers that "Seattle has well-paved streets, a thorough and satisfactory street car system, large and handsome business blocks, and residence districts adorned by palatial homes and green and velvety lawns." [8]

Electric rail lines also connected Seattle to communities to the north and south of the city. An interurban train ran between Seattle and Tacoma, and the completion in 1910 of a line from Seattle to Everett further opened opportunities for growth, encouraging development in new communities such as Alderwood Manor. [9]

Intra-city Transporation, Seattle, 1890-1941.

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle:

University of Washington Press, 1944)]

City Parks

Another development in early twentieth-century Seattle was the creation of the city's park system. As early as 1884, the Denny Family had donated a five-acre tract located at the foot of what is now Battery Street. Although first used as a cemetery, this parcel became Denny Park, a "verdant oasis" that featured the headquarters building of the board of park commissioners. The park commissioners also developed Volunteer Park, at the north end of Capitol Hill, and Woodland Park, east of Green Lake. Located outside the city limits, these reserves became accessible by streetcar lines. Additional acquisitions included Washington Park -- which is now the Arboretum -- Ravenna Park, and Leschi Park. [10]

Regrading

Fom the 1880s through 1910, the city limits grew dramatically, extending northward past Green Lake and southward to West Roxbury and Juniper streets. The commercial district expanded eastward away from the waterfront, as the shoreline became increasingly devoted to shipping and manufacturing. It also moved northward, toward Denny Hill. During the early twentieth century, Seattle's hills blocked further expansion of the city. In some places, the grades on streets over the hills measured 20 per cent, making transportation, as well as construction, difficult. [11]

[Source: V.V. Tarbill, "Mountain-Moving in Seattle," Harvard Business Review, July, 1930.] |

City engineers addressed this problem with extensive regrading projects, radically altering the topography of the city. As historian Clarence B. Bagley pointed out, during the early twentieth century the business section of Seattle became "one vast reclamation project." As he defined it, this area extended from Denny Way and the foot of Queen Anne Hill on the north to the Duwamish River toward the south. [12] Two of the most noteworthy reclamation projects included the Denny and Jackson Street regrades.

Reginald H. Thomson supervised much of this work. He was a civic-minded visionary -- a leader reminiscent of Arthur Denny. Born in Indiana, Thomson arrived in Seattle in 1881 at the age of 26. He dreamed of building a large city on Puget Sound, and investigated a number of possibilities, including Bellingham, Everett, and Tacoma, before settling on Seattle. He became City Engineer in 1892, quickly developing a reputation for dedication. "Thompson is a man who loves work," noted one observer, who further characterized him as "the greatest influence in Seattle." [13] Within two years he garnered support for the project to level Denny Hill, which presented a considerable barrier to northward expansion of the city. [14]

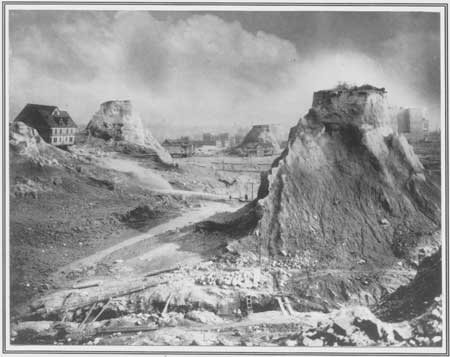

This leveling -- called the Denny Regrade -- proceeded in two stages: 1902-1910 and 1929-1930. By 1905, engineers had removed the west side of the hill, leaving the Washington Hotel precariously perched 100 feet above Second Avenue. This massive amount of earth was moved by hydraulics. Engineers used sluicing techniques similar to those used in gold mining, drawing water from Lake Union by large electric pumps through woodstave pipes. The water sprayed from hoses that featured a pressure of approximately 125 pounds at the nozzle, washing clay and rocks down into flumes and a central tunnel. Heralded as a monumental engineering feat, the Denny Regrade created more than 30 blocks of level land for new construction. [15]

Between 1900 and 1914, Thomson also transformed the southern end of the city. Called the Jackson Street Regrade, this project resurfaced and cut down approximately fifty blocks between Main Street on the north and Judkins Street on the south, and Twelfth Avenue on the east and Fourth Avenue on the west. The Jackson Street Regrade resulted in the removal of approximately five million cubic yards of earth at a cost of $471,547.10. A smaller regrade at Dearborn Street also removed more than one million cubic yards of earth, leveling areas for new construction. These projects improved access to the waterfront, Rainier Valley, and Lake Washington. According to Bagley, the regrade projects were among Thomson's most notable achievements -- and they dramatically changed the look of the city. [16]

Engineers used much of the earth removed from the regrades to fill the tideflats, a process that changed the appearance of the waterfront. The filled tideflats encouraged further development of rail yards and terminals -- and this expansion forced the relocation of ethnic groups, including Japanese and Chinese, that had resided and worked around Washington and King streets. The growth of an industrial complex in this area pushed them east of Fifth Avenue, where they formed a new community, now called the International District. [17]

As a result of the regrades, the city was level enough by 1910 to accommodate automobiles, which greatly increased the volume and speed of land transportation. Most land traffic in the Puget Sound area flowed through Seattle, further securing its status as the metropolis of the region. [18]

Engineers used slucing methods drawn from placer mining

to level the hills of Seattle.

Pictured here is the Denny Regrade,

early twentieth century.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division,

University of Washington)

Sewage, Water, and Electricity

As City Engineer, Thomson's chief concerns were sewage, water, and electricity. He was alarmed by the longstanding practice of individuals and businesses dumping waste into Lake Washington, which had no natural outlet. He suggested that sewage be discharged at West Point, at the edge of Fort Lawton on Magnolia Bluff, since the deep and constant current there could carry waste into Puget Sound. After lengthy negotiations with the U.S. Army, Thomson won approval to run sewer lines out to West Point. [19]

Providing for the expanding city was a major issue in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Before Thomson became City Engineer, Seattle had relied on a number of early water systems, included the operations of the Spring Hill Water Company. This firm secured its supply of water from the west slope of First Hill, storing it in wooden tanks in the south end of the city. In 1886, the company also constructed a pumping station at Lake Washington and a reservoir at Beacon Hill. Four years later, the city purchased the Spring Hill Water Company's system. By that time, city officials had already looked to the Cedar River, which flowed out of the Cascade Mountains, as the ultimate source of water supply. One of his first tasks as City Engineer was to design a plan for its development. A citywide fight over public versus private construction and management delayed the project until the late 1890s. [20]

In 1899, the city contracted with the Pacific Bridge Company to construct the headworks, dam, and pipeline. It also hired Smith, Wakefield & David to build the reservoirs in Lincoln and Volunteer parks. In 1901, the system went into commission, delivering 22 million gallons of water per day. By the end of the decade, however, city officials realized that this amount was not sufficient for the needs of the growing metropolis, and a second pipeline was constructed in 1909. By 1916, the expanded system had delivered 66 million gallons per day. [21]

Thomson also tackled the issue of electricity. In the early twentieth century, Seattle Electric -- a predecessor company of Puget Sound Energy -- enjoyed a near monopoly on electric power as well as public transportation. Thomson, however, wanted the city to build a hydroelectric plant at Cedar River, and he garnered support among city officials and residents. In 1902, voters decided in favor of the city power plant. [22]

Harbor and Waterway Improvements

During the early twentieth century, construction of the Panama Canal encouraged cities along the West Coast to plan for increased maritime traffic. Seattle promoters, including local newspapers and the Chamber of Commerce, advocated setting up a municipal corporation to own, expand, and manage Seattle's harbor. This enthusiasm inspired Virgil Bogue, a civil engineer, to draw up the city's first comprehensive plan for harbor improvement in 1910. Bogue had enjoyed an impressive career, designing Prospect Park in Brooklyn with Frederick Law Olmsted. He also constructed a trans-Andean railroad in Peru, and had identified Stampede Pass in the Cascade Mountains for the passage of the railroad. [23]

Bogue's plan for Seattle's harbor included two large marinas on the central waterfront, one for ferries and Alaska steamers and the other for Seattle's "mosquito fleet" (a fleet of small ships). He further envisioned 1,500-foot coal docks and the addition of piers and slips at Lake Union, which would be transformed into an industrial waterway. His plan also included a 3,000-foot waterway between Shilshole and Salmon Bays in Ballard -- a project for which Erastus Brainerd had lobbied in 1902. Bogue's most ambitious idea was to develop seven 1,400-foot piers at Harbor Island, which could increase Seattle's annual marine commerce by seven times. "Seattle's harbor is Seattle's opportunity," he wrote. "With cheap power in abundance, and an inexhaustible supply of coal at her very gates and the vast resources of its hinterland, all that remains to be done by Seattle, the gateway to Alaska and the Orient, is to adopt a comprehensive scheme for its development." [24]

In 1910, Congress authorized construction of the Lake Washington Canal connecting Lake Washington and Lake Union to Puget Sound. The following year, voters in King County created the Port of Seattle and passed Bogue's plan. [25] These improvements to navigation and harbor facilities helped Seattle become a major port, ensuring the city's continued connections to the Far North and Asia.

In general, the expansion of Seattle's infrastructure during the early twentieth century accommodated the population growth spurred by the Klondike stampede and subsequent gold rushes in Alaska. As historian Murray Morgan explained, "without Brainerd, Seattle might not have tripled its population in a decade; ... without Thomson, it could not have handled the newcomers." [26]

Seattle, 1888

Poole Brothers Map, 1888. Darkened areas show city boundaries

concentrated to the west, along the water. Compare to 1909 map.

[Source: Seattle Public Library]

Seattle, 1909

USGS Map, 1909. Note increase in darkened areas,

indicating movement eastward and northward.

[Source: Seattle Public Library]

Seattle, 1850s-1910

Map illustrating the growth of Seattle from the early 1850s to 1910.

[Source: Special Collections Division, University of Washington]

Territoral Growth of Seattle, 1869-1942

Territorial Growth of Seattle: 1869 to 1942

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle:

University of Washington Press, 1944)]

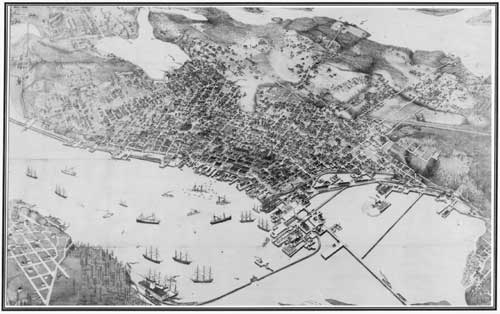

Bird's-eye view of Seattle, 1891

Bird's-eye view of Seattle in 1891, showing concentration

of development along the waterfront, two years after the fire.

[Source: Special Collections Division, University of Washington]

Population Density of Seattle, 1890

Population Density of Seattle, 1890

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle:

University of Washington Press, 1944)]

Population Density of Seattle, 1900

Population Density, Metropolitan Distrct, Seattle, 1900

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle:

University of Washington Press, 1944)]

Seattle Population Density, 1910

Population Density, Seattle, 1910

[Source: Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle:

University of Washington Press, 1944)]

End of Chapter Four

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003