|

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park Washington |

|

NPS photo | |

The cry of "Klondike gold!" first captured the world's imagination here in Seattle. It was July 1897. Tens of thousands of gold seekers soon poured through this small waterfront city. The Chamber of Commerce aggressively promoted Seattle as the "only place" to outfit for the goldfields. And sales did soar—to $25 million by early 1898. Shopkeepers piled their stock 10 feet deep on storefront boardwalks. Stampeders eagerly bought supplies and had one last hurrah!

They then boarded ships bound for the wild unknown of Alaska and Canada. This frenzy of activity helped to re-ignite the nation's depressed economy, and it ensured Seattle's position as a regional trade center.

Discover many fascinating reminders of 1890s Seattle today in the Pioneer Square National Historic District. Immerse yourself in the glory days of the Klondike Gold Rush that this national historical park commemorates.

Sudden, huge demand for outfits and goods for the Klondike forced merchants to pile their wares many feet deep on Seattle sidewalks. Stampeders scrambled to assemble their so-called "ton of goods" that Canada's Mounties would require before admitting gold-seekers to Canada, where the gold fields were. What might be called the "Klondike Outfit Rush" pulled—or jerked—Seattle out of economic depression. A number of today's national retailers got their big break here from the gold rush.

Long Trail to the Klondike

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

screamed headlines that sent over 100,000 people on a quest to pull themselves and the nation out of a three-year depression's economic ruin. But to strike it rich they would struggle against time, each other, and northern wilderness. US gold reserves plummeted in 1893. The stock market crashed. Ensuing panic left millions hungry, depressed, and destitute. Then came hope: on August 16, 1896, gold was discovered in northwestern Canada, near where the Klondike and Yukon rivers join. On July 17, 1897, the SS Portland reached Seattle with 68 rich miners and nearly two tons of gold! This promised adventure and quick wealth. For the lure of gold many risked all, even their lives, to be a part of the last grand adventure of its kind.

SEATTLE & BEYOND

The steamship Excelsior offloaded miners heavy with gold at San Francisco on the evening of July 14, 1897. The Portland docked at Seattle the morning of July 17, preceded by a reporter on a tugboat touting "more than a ton of solid gold on board." (In fact it was over two tons.) Among these first Klondikers were former Seattle YMCA Secretary Tom Lippy and his wife Salome. They ventured north on Tom's hunch in March 1896 just before the discovery. They brought back $80,000 and would eventually take nearly $2 million from the richest Klondike claim of all. The stampede was on, and all possible passage north to Alaska was booked.

Fewer than 3,000 took the all-water "rich man's route" from Seattle to St. Michael in Alaska, then up the Yukon to Dawson. It cost more than most stampeders could pay. Nearly 2,000 tried a difficult, all-land route from Edmonton. The handful who made It to Dawson took nearly two years, arriving after the rush was over. Most stampeders chose Chilkoot Pass or White Pass, and then floated down the Yukon.

DYEA & THE CHILKOOT TRAIL

Before the gold rush the Tlingit Nation controlled the strategic Chilkoot Pass trade route over the coast mountains to interior First Nation peoples' lands. The 33-mile Chilkoot Trail links tidewater Alaska to the Yukon River's Canadian headwaters—and a navigable route to the Klondike gold fields. Over 30,000 gold seekers toiled up its Golden Stairs, a hellish quarter-mile climb gaining 1,000 vertical feet, the last obstacle of the Chilkoot.

Most scaled the pass 20 to 40 times, shuttling their required ton of goods—a year's supply—north to the border for North West Mounted Police approval to enter Canada. No exact international boundary had been set, but Canada's regulation prevented starvation in the interior and protected its claim to all lands north of the passes. Conservationist John Muir was studying southeast Alaska glaciers when the stampede hit. Gold rush Dyea and Skagway "looked like anthills someone stirred with a stick," Muir wrote.

The Chilkoot Trail's fabled Golden Stairs humbled argonauts intent on the summit. This vivid image—an endless line of prospectors toting enormous loads like worker ants—became the Klondike Gold Rush icon. It took three months and 20 to 40 trips to carry their ton of goods over the pass.

SKAGWAY & WHITE PASS

A better port than Dyea, Skagway was the "Gateway to the Klondike." Wild, it had something for all. Confidence artists and thieves, led by Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith, and greedy merchants lightened the unwary stampeder's load. Up-to-date Skagway had electric lights and telephones. It boasted 80 saloons, three breweries, many brothels, and other service or supply businesses.

The White Pass Trail was 10 miles longer—but its summit less steep and 600 feet lower—than the Chilkoot Trail. Two months' overuse destroyed it. Its second life began as British investors started to build the White Pass and Yukon Route Railroad in May 1898. Rails reached the White Pass summit in February 1899, Bennett Lake in July 1899, and Whitehorse in July 1900. With the railroad open, development at Dyea and along the trails ceased. But by then the rush was over.

Chiefs Doniwak and Isaac of the Tlingit were pivotal in transmountain packing and trading as gold prospecting increased in Canada's interior. As the Klondike stampede intensified, demand for Native packers exceeded supply. Pack horses, aerial tramways, and other schemes would soon reduce the Tlingit's packing business.

Falsely dubbed "all-weather," the White Pass Trail—boulder fields, sharp rocks, and bogs—earned the name Dead Horse Trail. Over the 1897-98 winter 3,000 horses died on it "like mosguitoes in the first frost," Jack London wrote.

At the Chilkoot and White pass summits, Canada's Mounties gave properly outfitted stampeders official entry into Canada. "It didn't matter which one you took," said a stampeder who had traveled both trails, "you'd wished you had taken the other."

YUKON VIA BENNETT LAKE

It took three months just to cross the mountains to the interior. Then most of the 30,000 stampeders sat out the 1897-98 winter in tents by frozen lakes Lindeman, Bennett, or Tagish—still 550 miles from the gold fields. They built 7,124 boats from whipsawn green lumber and waited for lake ice to melt. Finally, on May 29, 1898, the motley flotilla set out. In the next few days five men died, and raging rapids near Whitehorse crushed 150 boats. After the rapids it was a long, relatively easy trip, but bugs and 22-hour sunlit days drove boaters nearly mad. Near Dawson some feuding parties split up—cutting in half even their boats and trypans. Then, finally, Dawson City!

Whipsawing trees into planks, stampeders built boats or rafts—and then waited for a long Arctic winter to end.

A hundred miles of lakes led into the Yukon River, where canyon rapids soon gave way to smooth water beyond Whitehorse.

DAWSON CITY & THE GOLD FIELDS

Before the gold rush a few Han First Nations people camped on the small island where the Yukon and Klondike rivers join. Prospecting in the area George Washington Carmack, Keish ("Skookum Jim" Mason), and Kaa Goox (Dawson Charlie) struck gold on August 16, 1896, on Rabbit (later re-named Bonanza) Creek. On August 17 they filed claims in Fortymile, the nearest town, 50 miles downriver. This sparked the first stampede as prospectors already in the interior got the news via the informal bush communication network. Former Fortymile trader and grubstaker Joseph Ladue shrewdly platted Dawson City and made a fortune selling lots.

Dawson City boomed. Soon it was Canada's largest city west of Winnipeg and north of Vancouver, its population 30,000 to 40,000. It stretched for two miles by the Yukon, bulging with goldseekers. Anything desired could be had—for a price: one fresh egg $5, one onion $2, whiskey $40 a gallon. However, most stampeders did not reach Dawson City until late June 1898, nearly two years after the big discovery, and prospectors already in the region had long since staked claim to the known gold fields. Many disillusioned stampeders simply sold their gear and supplies for steamboat fare to the outside, their visions of wealth washed away. Canadian historian Pierre Berton writes that many stampeders arrived in Dawson City and simply wandered about, utterly disoriented by its frantic activity, not bothering to prospect at all. Played out over such vast space and time, the adventure itself seems to have been, for many people, the biggest attraction of the Klondike Gold Rush. Mining was another story.

To get through the perennially frozen soil called permafrost, miners built fires to melt a shaft down to where the gold lay. Two men digging like this for a winter used 30 cords of firewood that they had to cut themselves (until the stampede's large labor pool arrived). Miners dug shafts down to the gold just above bedrock, deep below the layers of frozen muck and gravel. At bedrock, they tunneled out, "drifting," as it was called, along the gold-bearing gravels of the old stream course. Dirt and gold-bearing gravel, called "pay gravel," were hoisted out of the hole and piled separately for sluicing (washing away the dirt and gravel) in spring and summer, once sunlight thawed the dumps and streams. Reporting from right on the scene, journalist Tappan Adney wrote that—considering the cost of reaching the country and the cost of working the mines—"The Klondike is not a poor man's country."

Women and a few children joined the stampede. Many women who went north were spouses, mining partners, or business owners. Some prostitutes, styled as "actresses," went north to ply their trade.

In Dawson City and Seattle more fortunes were made off miners than by mining. By 1906 Klondike gold exceeded $108 million at $16 per ounce.

Seeing Gold Rush-era Seattle Today

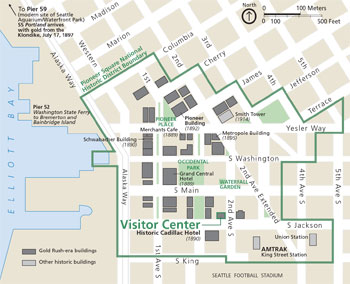

(click for larger map) |

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park—Seattle is located in the historic Cadillac Hotel, 319 Second Avenue South, two blocks north of the Seattle football stadium. Visitor center hours vary by season. Please visit www.nps.gov/klse for current information. It is closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Ask at the visitor center about the schedule of walking tours and other programs and activities. Exhibits and audiovisual programs there tell the story of Seattle's crucial role as the staging area for the Klondike Gold Rush.

Parking is available on the street and at several nearby locations. Bus stops, the train station, and local ferries are within walking distance.

The heart of gold rush Seattle, Pioneer Square National Historic District has shops, art galleries, restaurants, and book and antique stores. Many gold rush-era buildings still stand in the historic district today. To the north is Waterfront Park, the site where the steamship Portland docked in 1897 with the 68 miners whose cargo of gold launched the Klondike Gold Rush.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, programs, and services accessible to all. For information, ask at the visitor center or check our website.

Safety The park is located in downtown Seattle. Watch for traffic and take precautions appropriate to a major metropolitan area, especially with children. Be careful of uneven walking surfaces in the historic district. Firearms are prohibited in this park.

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Seattle) — June 30, 1976 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Foundation Statement, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska/Washington (April 2009)

Foundation Document Overview, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park — Seattle Unit, Washington (January 2017)

General Management Plan, Development Concept Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (September 1996)

Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush: A Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (HTML edition) (Lisa Mighetto, November 2003)

Junior Ranger (Ages 9-16), Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (HTML edition) (Frank B. Norris, 1996)

Museum Management Plan, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Brooke Childrey, Tracie Cobb, Steve Floray, Diane Nicholson, Paul Rogers and Keith Routley, 2008)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Pioneer Square Historic District (Boundary Increase) (Elizabeth Walton Potter, December 1976)

Pioneer Square-Skid Road District (Margaret A. Corley, July 1969)

River of Gold: The Impact of the Klondike Gold Rush on the Pacific Northwest (J. Kingston Pierce, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 11 No. 2, Summer 1997; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Seattle's Stake in the Klondike Gold Rush: A 3rd - 6th grade Integrated Curriculum (May 2005)

klse/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025