|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 11:

Regaining Ground: Leases and Special Use Permits

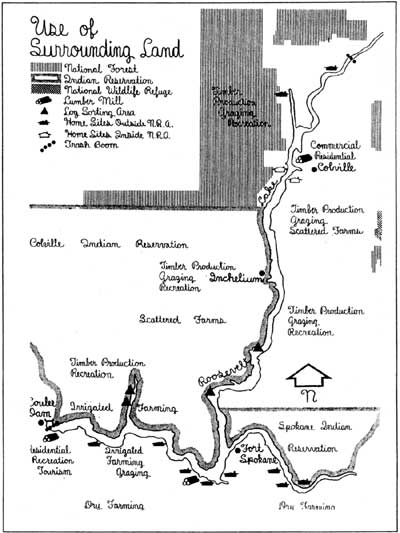

Many types of special use permits and leases soon will be a thing of the past at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO). Once considered a useful way to encourage development and use of federally owned lands, they are now seen as encouraging privatization of public lands. Over the years, such permits have allowed individuals and companies to use Lake Roosevelt shore lands for industrial, agricultural, and recreational activities. Applications for special use permits began before the National Park Service had even taken responsibility for the recreational development of the new reservoir, and uses gradually multiplied in the ensuing decades. Along with permitted activities came illegal use of federal lands, either through encroachment (an unauthorized use of public lands) or trespass (a more serious violation that usually is handled through the legal process). The problem with encroachments can be attributed partially to the physical configuration of the park, a narrow strip of land sandwiched between the high-water line and a largely unmarked boundary generally twenty feet higher in elevation. Lack of consistent policies and enforcement also contributed to the eventual proliferation of encroachment cases. Park Service philosophy and policies changed by the 1980s to restrict special uses on park lands. When LARO began to revise its policies to bring them into conformance with Park Service guidelines, the park met strong resistance from permittees, adjacent property owners, and local officials. The resulting struggle tested wills, tempers, and managerial skills and ultimately changed the appearance and operating philosophy of the park. [1]

Developing Policy for Special Park Uses,

1940s

|

As a general policy it is agreed that a special

use of the Reservoir Area by an individual is a privilege and not a

right, and that each special use must be justified in the public

interest. Inquiries proposing apparent detrimental uses of the Area

will be rejected by the Park Service without the formality of preparing

standard applications.

-- Claude E. Greider, NPS Recreation Planner, April 23, 1943 [4] |

Requests for special use permits began arriving before water filled the newly cleared reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam. At that time, the Park Service was working on field studies and initial plans for the recreation area, but it had not yet been assigned the job of development and administration. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation continued to administer the area until the two agencies signed a memorandum of agreement in July 1942. During negotiations for the interagency agreement, Reclamation insisted that all funds generated by special use permits go to a special account to benefit the Columbia Basin Project. [2]

Even after the agreement was signed, the Park Service did not immediately take over the administration of special use permits. In August 1942, Landscape Architect Philip Kearney, the sole Park Service employee then at the reservoir, reported that there had been several applications for permits in the past few days, including one for a sawmill and tramway at Kettle Falls on lands considered for recreational development. F. A. Banks, Reclamation Supervising Engineer, was pressuring the Park Service to handle these permits, but Kearney did not yet have either authority or a formal policy. He appealed to the regional office for help. Claude E. Greider, Park Service Recreation Planner and later first LARO Superintendent, suggested that Kearney send all applications to the Regional Director with a full report and recommendations. When considering the sawmill application, he should assess the need for a mill in that location, the integrity of the applicant, and the possibility of finding an alternate location that would not compromise recreational values. [3]

Greider's arrival at the reservoir in late December 1942 doubled the Park Service staff in the area. He took over administrative responsibilities and by early 1943 had developed guidelines for special use permits. Greider's primary concerns were that no special use should conflict with Reclamation's primary project needs or the Park Service's plans for recreational development. He laid out a general policy with the underlying premise that a special use of federal land was a privilege instead of a right. Did it contribute to needs of area residents economically, socially, or for recreation? Was it safe and fair? Would it set a bad precedent? What were the potential effects on wildlife and scenery? Was there an area outside the reservoir that would fill the applicant's need equally well? [5]

Special use permit fees, 1943:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the next year, Greider worked on both the permit application form and a schedule of fees, both of which needed Reclamation approval. After the form worked its way through various levels of bureaucracy, Banks informed Greider in April 1944 that it had been approved and he would soon be receiving five hundred mimeographed copies. The only major change was the deletion of grazing and agricultural permits for lands adjoining reservations pending determination of Indian rights to these areas. The Reclamation counsel also added a standard clause releasing the United States from responsibility for any damage the permittee might incur from fluctuating lake levels. The initial fee schedule covering six possible uses quickly expanded to eleven as requests rolled in during 1943. Greider recommended the fees apply to permits of one year or less, with applicants having the option to renew for an additional four years. He believed that anything longer than five years needed to be covered under a license, lease, or easement, with the fee based on the current value of the land. [6]

The 1946 Tri-Party Agreement mandated that the Park Service take primary responsibility for special use permits involving federal lands and waters. The agency was instructed to issue permits for legitimate industrial and recreational purposes, along with agricultural and grazing uses, for lands in the Coulee Dam Recreational Area. The Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), however, handled all agricultural, grazing, and log dump permits in the Indian Zones. The Park Service also assumed responsibility for all permits and leases issued by Reclamation to date. Each permit had to contain clauses to protect Reclamation from responsibility for damages and to place the interests of the Columbia Basin Project above all other uses. Finally, all payments collected by the Park Service were to be deposited into a special account that was conveyed periodically to Reclamation. [7]

Although the two agencies discussed transferring all special use permits to the Park Service in 1943, LARO did not assume full administrative control until 1947. The transfer eliminated the need for Reclamation's concurrence on any permits. The Park Service notified all permittees and leaseholders of this change. The administration of permits was not as well coordinated between LARO and OIA, however, and in May 1950 two LARO rangers met with the Superintendent of the Colville Agency to discuss his policy of allowing use of Indian Zone lands without permits. "This inconsistency in administration of area lands has caused us some embarrassment with the public," admitted Superintendent Greider. The two agencies took steps to apply permit policies more consistently. [9]

Early Permits for Agriculture, Industry, and

Transportation

Within a few years after the establishment of LARO, livestock posed a considerable trespass problem for federal land managers. Large areas between the high water level and the 1,310 line had grasses suitable for grazing, attractive to cattle on adjoining lands. It was also attractive to the ranchers and farmers who viewed the vacant, unfenced land as available for free use. Reclamation and the Park Service discussed ways to deal with the problem, including increased patrols, asking county commissioners to establish herd districts, and securing public cooperation through education. Initially, LARO was reluctant to consider opening these lands for grazing since much of the shore land was already overgrazed by cattle. After consideration, however, Greider concluded that grazing could be allowed below the 1,310 line in certain areas, with the stipulation that the tracts be fenced to prevent animals from wandering onto adjacent government land. He believed that containing the livestock would enable LARO to control both overgrazing and noxious weeds. Greider also suggested that some of the best agricultural lands along the shore could be leased for gardens. [10]

|

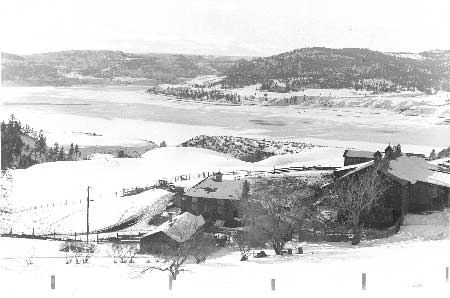

| Farm bordering LARO, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

LARO considered the bottomland along the Kettle River as "an extreme public nuisance" at the time the agency took over administration. The unfenced area was overgrazed and infested with noxious weeds, causing neighboring farmers to complain. Individual leases did not seem feasible, so the Park Service signed a long-term lease for seventeen hundred acres in January 1948 with the Kettle-Stevens Soil Conservation District, which then subleased the land to the Kettle River Grazing Association. After the Soil Conservation Service drew up rehabilitation plans, farmers undertook the work of fencing and building up the land with legume crops. The Park Service charged just a token fee for the first four years to encourage the work, then began charging in 1952 at the rate of fifty-five cents per animal per month for grazing. By that time, the Park Service believed the program to be a success for both the government and for the lessees. "It is enabling the National Park Service to maintain a normal farm picture along the Kettle River at a minimum cost to the government, and places the area under close administrative control," wrote LARO's Chief Ranger. The lease ran through 1957 and then was renewable on an annual basis for another ten years. [11]

The OIA was particularly concerned with keeping open options for industrial and agricultural uses of lands in the Indian Zones. The agency knew the abundant timber on the reservations provided a source of revenue for the tribes, supplying area mills with an annual cut of at least thirty-five million feet. Because the tribes depended on this income, OIA insisted that recreation planning at Lake Roosevelt not interfere with the development of the timber industry on the reservations, including log dumps, transportation of logs and lumber on the lake, and milling beside the lake. When the Park Service tried to shut down a log dump at Sanpoil Bay in 1943 due to its location at a proposed recreation site, OIA was quick to disagree. The two agencies sparred over this site but resolved the general issue three years later when the Tri-Party Agreement gave OIA responsibility for permitting log dumps in the Indian Zones at sites selected in consultation with the Park Service. Livestock grazing also was important to the tribes and formed a major use of shore lands adjoining the reservations. [12]

|

| Sawmill at the South Marina site, November 1956. This was one of several sawmills that were granted permits to operate along Lake Roosevelt. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center (HFC WASO-B-343). |

The Park Service kept industrial needs in mind when formulating early plans for the development of Lake Roosevelt. Kearney identified three areas for concentration of industrial uses: from Spring Canyon to Plum, the mouth of Hawk Creek, and the original townsite of Kettle Falls. He also suggested that industries would want to use water transportation for both raw materials and finished products. Lincoln Lumber Company already operated a mill at Hawk Creek in 1941, and within three years there were three more mills running beside the lake. The lumber industry boomed after the end of World War II, and the forests around Lake Roosevelt were harvested heavily. There were twenty-seven permitted logging uses in 1948, and by 1951 demand was so high that some dumps had to serve two operators. [13]

While the Park Service was willing to grant permits for industrial use of federal lands, the agency also had to deal with the resulting downside of permits — encroachments and trespasses. The post-war increase in logging brought problems of trespassing on government lands at LARO, an issue that has plagued land managers since. The OIA told the Park Service of timber trespass at Cedonia, Fall Creek, and other locations in the fall of 1945, where loggers evidently had ignored the need for a permit and cleared the reservoir shore for use as landings. By December the loggers sent a check for $98.20 to the Park Service to cover 19,640 feet of pine logs taken, valued at $5 per thousand board feet. Two years later, Superintendent Greider ruled that a Deer Park lumber company's cutting of 65,000 board feet on recreation area lands appeared to be accidental, based on an error in running the boundary line, and he assessed the company $295. When the same company trespassed again in 1955, the Park Service recommended a fine of double the stumpage rate. [14]

The long body of calm water formed by Grand Coulee Dam offered opportunities for transportation, with tugboats and barges providing a convenient means of moving logs and lumber for the growing timber industry. One of the first to enter this market was Albert "Cap" Lafferty, an experienced operator who had been running tugs on Lake Coeur d'Alene in Idaho since 1918. He was quick to see the potential at the new Columbia River Reservoir and received his certification from the Interstate Commerce Commission in August 1941. After the Great Northern Railway agreed to extend its line to the lakeshore at Kettle Falls, Lafferty established his headquarters there. The Park Service gave him a special use permit in November 1943 to build barges at a site on the south bank of the Spokane River. The following year, Reclamation signed leases with Lafferty for a spur track at the Kettle Falls bridge as well as a tugboat terminal near Lincoln Lumber Company. [15]

Problems arose within a few years. Although both Reclamation and the Park Service approved Lafferty's request in 1945 to build employee housing at the terminal in Kettle Falls, by April 1947 Greider told Lafferty that he would have to remove the temporary housing, contending that LARO had approved neither the location nor the sub-standard construction. Lafferty agreed to comply with Park Service regulations, but Greider was unimpressed. "By his evasive actions over a long period, we feel he has no intention of complying," Greider wrote. "His promise of cooperation . . . is empty of any sincerity." Evidently the Park Service had been watching Lafferty's lease for some time but did not want to make an issue of it until the agency gained full jurisdiction over the recreation area. Once this happened, Greider moved to resolve it speedily, hoping to demonstrate to others that the Park Service had the courage to enforce its lease provisions. [16]

The issue was not resolved quickly, however. After receiving no response from Lafferty, Greider cancelled the lease in August 1947. At that time, the tug company had not only retained the three shacks that the Park Service found objectionable but had also added a fourth building plus a six-hundred-foot access road across federal land. Lafferty complained that LARO was "very abrupt" with its cancellation and was not taking into account the dismal economic climate that limited his ability to develop his business properly. He asked for a continuation of the lease. Through inaction, the office of the National Park Service Director effectively granted an extension, causing Greider to complain three months later that the delay was "developing into an acute situation" for LARO, and he asked the regional office to intervene. Greider was feeling under siege at this time, hampered by lack of funding for the recreation area yet pushed by local residents who wanted immediate development. Lafferty's lease was one more stress he did not need. "Possibly age and fiscal uncertainties are finally making me edgy," Greider confided to Regional Director Herb Maier. He continued:

|

| Unloading lumber from barge at Lafferty Transportation Company docks at Kettle Falls, 1955. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center (HFC WASO-B-350). |

But delays of so many different kinds with relation to this area have created an explosive condition with relation to the public. Any one of a number of fuses might touch off the works if the match is applied. One way to forestall this is to keep a tight check rain [sic] on uncooperative elements by demonstrating efficient operation — such as it is. [17]

Lafferty appealed the final cancellation of his lease in January 1948 and was told he would have to reapply to Greider for a new lease. Instead, after various discussions, LARO bypassed Lafferty and leased the land to the Great Northern Railway, which then subleased to the tug operations. Greider was relieved: "I feel that the Great Northern can handle Mr. Lafferty just as effectively as we can with much less controversy." [18]

A number of individuals applied to LARO for permits to install water pumps, for both domestic use and irrigation. In addition to the Park Service permit, they also had to get a permit from the state for the amount of water to be withdrawn. Some installed pumps in trespass and when caught, they were encouraged to get the proper permits. Greider assured one such violator that LARO was "anxious to cooperate with any individual desiring to make proper use of Coulee Dam Recreational Area." Permits could be approved quickly if their locations did not interfere with planned recreational use. By 1947, however, Greider began to have concerns about future impacts from these leases. Although there were only nine permits or leases for pumps at that time, he foresaw potential problems if people claimed that a state permit gave them a right to use federal land. LARO continued to issue these permits, however, and water withdrawal systems have caused few problems for LARO over the years. They remain one of the few special uses still allowed at the park. [19]

Early Recreational Permits

In addition to industrial and agricultural uses, the Park Service hoped to encourage recreational use of the reservoir lands by allowing leases for summer cabin sites. Although requests began coming in before the agency had even assumed full administrative authority for the area, LARO staff did not begin to concentrate on this issue until 1952. There were a number of concerns that needed resolution before leasing could begin. Among the first of these were questions about the Park Service policy of clustering cabin sites in groups of ten or more. R. T. Paine, president of the Colville Chamber of Commerce, understood the practical reasons for this policy, especially when locating roads and utilities. But he said that local people did not favor such groupings, claiming "that if a person is primarily interested in paved roads and utility developments and groups of homes he has them right on the block on which he lives." The Chamber members suggested instead that LARO set aside all areas considered for public recreational use and then open the rest to summer homes, accelerating development of the area. [20]

Park Service reaction to these ideas was mixed. Thomas J. Allen, National Park Service Assistant Director, explained the agency's policy of arranging the sites to maximize the attraction to both cabin occupants and visitors to Lake Roosevelt. He assured Paine that the Park Service would consider applications for specific sites, considering the merits of each one. Allen told the Regional Director that Paine's ideas had merit, and the agency would like to see if they would help solve the summer home problem in one recreation area, namely LARO. Still, he was troubled by the need to formulate policy for summer homes in the new national recreation areas (NRAs), where he saw the need to balance Park Service planning standards against demands from users, public relations, and delays engendered by prolonged periods of planning. Greider realized that he needed to make progress on the summer home lots at Lake Roosevelt, but he was concerned about a lack of policy, especially since it looked like Allen was willing to abandon the established policy of grouping homes. [21]

Greider and his staff began looking at potential summer home sites in the summer of 1952. They were concerned about the possibility of landslides, so they enlisted the help of Fred Jones, from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), to examine all sites under consideration. The Park Service also sent Harold Fowler, Landscape Architect from the San Francisco office, to look over potential sites in the Kettle Falls District. The recommendations included the North Gorge area (25-30 homes); Nancy Creek (3-4 homes, with crowding); Kettle Falls (5-6 homes at a bare and hot site); Kettle River; Barstow Flats (40-50 homes); and Colville River (4-6 homes). In addition, the group recommended an area on the Spokane Indian Reservation about one mile north of the Spokane River, with access off Highway 25. They considered this site so desirable that they included it despite the difficulty they anticipated in working out an agreement with the Spokane Tribe. The group also eliminated Marcus Island from consideration since Jones believed that the island would disappear within a short time. A few weeks later, LARO Chief Ranger Robert Coombs flew Fowler over the Spokane Arm where he selected three additional sites suitable for 50-80 homes. Greider, however, discounted these sites both because of landslide potential and because LARO had not yet selected areas for recreational development along the Spokane Arm. [22]

Greider added three more areas to the list of potential summer home sites during December 1952 and January 1953. These included the Sherman Creek area, Rickey Point, and Bossburg. LARO spent considerable time working out the problems connected with the Sherman Creek sites since interested applicants included eight or nine prominent citizens from the Colville area. Greider warned that the access road would be costly, but those interested did not seem concerned about bearing this expense. The LARO Superintendent initially did not believe that the Park Service should build such roads because he could not justify the expenditure of public funds to benefit a select few. He later reconsidered and told a group wanting to use the Sherman Creek area that Park Service policy called for the agency to build permanent roads to cabin sites. Due to lack of funds, however, this could not be done for at least a year, and he suggested that the group do rough clearing on the right-of-way to allow them temporary access. [23]

By the spring of 1953, the summer home list had been considerably revised. All of those sites considered the previous August were dropped, replaced with Sherman Creek, Rickey Point, and Bossburg, with a fourth site at Kettle Bridge to be added that summer. Greider expected that Rickey Point would eventually include seventy sites, while Sherman Creek would have ten and Bossburg up to fourteen. [24]

As the Park Service worked on developing its policies for summer cabins, LARO personnel consulted with U.S. Forest Service officials, both locally and regionally, to see how that agency handled such permits. They found that the Forest Service no longer mandated standard lot sizes but instead let the size vary according to topography, usually three-quarters to one acre. The agency provided all access roads to avoid problems with substandard roads that often ruined scenic values of an area. It also gave permittees assistance with planning docks and other marine facilities, again to avoid substandard construction. The agency allowed one residence per lot, along with garages, barns, guest houses, and other structures. Leases had been reduced to twenty years, but following public complaints the Forest Service was considering raising the term to ninety-nine years again. [25]

|

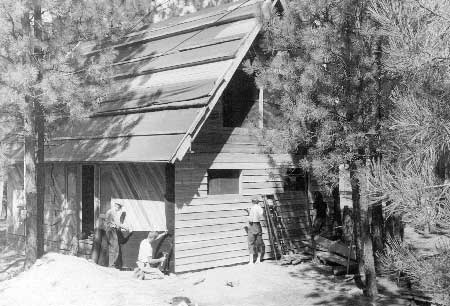

| C. Buddrius family working on their summer cabin at Rickey Point, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

LARO guidelines, when finally released, did not follow Forest Service precedent on many issues. Lot sizes were kept to approximately one-half acre, with annual rents of $25. The term of the lease was for twenty years, with only one attractive, well-built home allowed on each lot. Permittees had to clear all building plans through both LARO and the Department of Health, and all docks, fences, and other structures needed the park's approval. LARO agreed to locate all access roads, but the permittee had to build these initially. Although the Forest Service tried to leave a buffer strip between buildings and water to encourage public use of the beaches, LARO planned to limit such public access at Rickey Point. "It would be undesirable to have the general public utilizing the subdivision water front and other facilities which may be provided by the residents for their use," suggested the Regional Landscape Architect. LARO policy on this point changed dramatically over the next thirty years. [26]

Despite the progress made in summer home development during 1952, Greider was frustrated by delays the following spring. He needed approval for a special use form for these cabins, submitted in January, and he needed help from the regional office to stake lots. With the arrival of spring, local people were expecting approval of permits so they could begin building, and Greider feared that the Park Service would be embarrassed if there were a delay. There were further setbacks when USGS geologist Jones condemned nearly one-third of the Rickey Point development because of landslide potential. Additional problems with rights-of-way held up access roads. Greider finally received approval for the cabin developments in April 1953, and he began staking lots immediately. [27]

Greider noted two changes in policy from that originally announced in the fall of 1952: lease rates had increased to $35 per year and the Park Service had reverted to its old policy of locating cabin sites in groups of ten or more. Under the policy previously advertised for LARO, however, several individuals had applied for isolated sites that would accommodate up to four cabins. Greider believed that the park needed to process these applications as originally announced to avoid further embarrassment. It is not clear if the Park Service approved these exceptions or not, but apparently no individuals took up leases on isolated lots at LARO. Instead, the park confined its plans to Sherman Creek, Rickey Point, and Bossburg, with developments limited eventually to just the first two locations. [28]

During the next few years, the public continued to pressure LARO for additional cabin sites, none of which were approved. The Park Service developed plans for a group of summer homes at Keller Ferry in 1955, and two years later individuals were asking for sites at Haag Cove and on the Spokane Arm. Although LARO Superintendent Hugh Peyton supported the Keller Ferry plans, he resisted increased development elsewhere, fearing that it would preclude future public use. To prevent just such a situation, he had LARO staff put two small campgrounds at Haag Cove in April 1957, complete with a sign. Peyton referred to the installation of these minor developments as "homesteading," and he did this in various places to keep sites in public hands. He also noted another group that was using political pressure to secure first choice of cabin locations on the Spokane Arm. This caused him to suggest public drawings for assigning cabin sites. "By using an impartial method of intermittently allocating these available sites," he suggested, "we could point to our fair method of taking care of this situation and be able to distract from the strength of selfish pressure groups which are springing up like toadstools around the area." The Director's Office approved these proposed changes, along with rewording of the lease to identify these developments as vacation home sites rather than residential lots. [29]

Adjacent landowners occasionally trespassed on government lands, knowingly and unknowingly, when building cabins. In one case, Mr. and Mrs. Paul Moody acquired land at the mouth of Fifteen Mile Creek around 1940, before the boundary line was clear, and they began construction four years later on what they thought was their property. They believed that LARO agreed with their assessment since a ranger never questioned the location of their cabin when he told them ca.1947 that they needed a permit for their dock. By 1958, however, it was clear that the building was on federal lands. Reclamation Field Solicitor Paul Lemargie took a hard line, telling Moody that he could not legally lease the land and asking him how soon they could move their cabin. This provoked an emotional plea to President Eisenhower from the now-retired couple who professed to be "heartbroken" at the thought of tearing down the cabin they had spent fifteen years building. Thus began more than fifteen years of permits, cancellations, and appeals. [30]

The Moody trespass, along with several similar ones, demonstrates the inconsistencies of Park Service permits and enforcement, not just at LARO but also at the regional and national levels. Superintendent Homer Robinson believed that Moody should have known that he was building on federal land since his cabin sat just twenty-five feet from the water, approximately one hundred fifty feet inside the boundary. He suggested that LARO could offer Moody a permit for up to twenty-five years, but he thought that twenty years should be the maximum. "It must be recognized that such action might establish a precedent detrimental to our best interests," he warned. Robinson argued that other trespassers should be given similar consideration, especially since one man was elderly, in poor health, and living on welfare. The case went to National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth, who offered the Moodys a five-year permit with the stipulation that the cabin be removed or revert to the government at the end of the period. [31]

The case did not end that simply. Another emotional plea to the President in 1961 bought the Moodys an additional five years. When the cabin still stood in 1968, LARO Superintendent David Richie had lost his patience with the Moodys and a similar case. He questioned whether these trespasses were "entirely innocent" since the owners should have gotten a boundary survey before building. Furthermore, if the Park Service believed that the land at LARO was for the use of the public, the agency should not tolerate such prolonged trespasses. The regional office overruled Richie, saying that there was no indication that the Moodys' trespass was deliberate and LARO had no plans for public recreation at the site. The "further pursuit of cabin removal seems to place the Government in a very arbitrary position," wrote Raymond O. Mulvany, Acting Regional Director. He asked Richie to keep renewing the special use permits for the lifetime of the tenants, deleting the stipulation that the cabin be removed. [32] The then-elderly couple moved to a new cabin on their own land in 1973, but removal of the offending cabin took at least another year. The foundation, bridge, and outhouse, located on federal land, remained at least several more years. [33]

Since the 1940s, LARO has permitted organizations to secure long-term leases for group camps. Boy Scouts of the Grand Coulee Dam district were the first to apply, securing a one-year special use permit in 1944 for a camp on the northern shore of the reservoir across from Spring Canyon. Four years later, Troop 79 of Wilbur applied for a twenty-year lease for a permanent youth camp along the lake between Jones Bay and Hanson Harbor. Their plans included a lodge, dock, campfire circle, sanitation, water supply, and play area. When not needed by the scouts, the group planned to make the facilities available to other youth groups, including girls. While Greider encouraged such use of park lands, staffers in the regional office had mixed reactions. Despite these differences, LARO approved both the special use permit and the building plans in 1949, in time for the group to pour the foundation before freezing weather set in. [34]

The following year the Council of Churches in Seattle asked for a long-term lease for a summer camp at Lake Roosevelt. Greider initially recommended approval of the lease because of the program's character and statewide nature. The Park Service wanted to see some preliminary plans before approving the lease, but the Council said that it needed the lease before it could proceed with fundraising and planning. The agency believed it should make every effort to help them develop good plans, and the regional office considered having a landscape architect meet with the camp committee to discuss layout and planning. The issues were the same in 1952, with LARO still wanting to see some plans before granting the lease. At some point, the Council dropped the idea and the camp was never built. [35]

LARO permitted another group facility, Camp Na-Bor-Lee, in 1966 when a civic group from Stevens County leased land fifteen miles north of Fort Spokane. As a gesture of both goodwill and good public relations, the Park Service assisted the group in preparing initial plans. The agency stipulated that a substantial part of the development work needed to be completed within five years. [36]

Many who had vacation cabins, either on federal lands or adjoining private lands, wanted to build docks to provide mooring for boats as well as enjoyment for swimmers. The permitting process was easy initially. Reclamation policy in 1943 required a drawing showing the location of the site in relation to the nearest section line. It is probable that the Park Service continued this simple policy when it took over special use permits because there was no need for excessive regulations with very few docks on many miles of undeveloped shoreline. Permits became more complicated by 1963 when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reminded LARO that anyone applying to do work, primarily dock construction, within the navigable waters of the Columbia River system needed to obtain Corps approval. The Park Service could not waive this requirement for permittees, nor could the Corps waive the need for a special use permit from the Park Service. Despite these extra restrictions, LARO officials recognized by the mid-1960s that individual docks had increased so greatly that they needed to be consolidated in "unit locations" to keep the shoreline free for public use. The park began developing policies and standards for community docks in 1967. [37]

Attempts to Gain Control of Special Park Uses,

1960s and 1970s

The somewhat lax approach to special use permits and leases at LARO began to change in the 1960s, followed by increasing restrictions in subsequent decades. After an extensive comment period, the Department of the Interior adopted new regulations in 1966 governing cabins on federal lands. Under the new rules, federal agencies could not cancel leases prior to the termination date. They could, however, renew such leases if this appeared to be in the public interest. [38]

Passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 led to a dramatic increase in cabin lease fees at LARO. Under the new requirements, fees for private uses of public lands had to be based on current market value and determined using competitive commercial practices. LARO's $35 annual fee obviously did not meet these standards, so the park staff worked with the Stevens County assessor to arrive at an appraisal of $7500 per lot. Using a 6 percent rate of return, the staff then determined the new fee to be $450 per year, effective May 1977. They realized the hardship of such a large increase, however, and phased it in over a three-year period. Thus, the first year cost $150, the second $300, and the third full price. The Park Service agreed to renew leases for five-year periods, but with the entire lease program under review, the agency cautioned lessees not to expect lease extensions to continue indefinitely. Lessee reaction to the increased fees was not documented. [39]

Under the Tri-Party Agreement of 1946, leases and special use permits for reservation lands were administered by two different agencies: OIA (later the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA) was in charge of all agricultural, grazing, and log dump permits, while the Park Service administered all other uses. This began to change with the Solicitor's Opinion in 1974 that directed the three agencies to negotiate a new management agreement to include both the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) and Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI). Initial negotiations produced no results, so the three agencies met in March 1977 to determine jurisdiction for special use permits for freeboard lands in the Indian Zones. They agreed that BIA would continue with its previous responsibilities, but Reclamation took over all other Indian Zone permits from the Park Service. The Bureau and Park Service then drew up another agreement giving the Park Service administration of all permits outside the Indian Zones. [40]

By the early 1970s, LARO staff realized the need to get control of special use permits and, even more importantly, associated encroachments. Previous administrations had tried to correct the difficult situation. In 1957, for instance, the superintendent reported that, with 172 permits, his staff had spent considerable time that year locating boundaries for citizens who questioned lines. Superintendent Homer Robinson knew that marking the boundary would help but recognized the futility of such a proposition given the total project cost of nearly $1 million. The park staff made progress in 1972 inventorying permits and checking status and transgressions, but they soon realized the need for a Land Management Specialist to work at this full-time. [41]

Daniel J. Farrell arrived in June 1974 to fill this new position. He found approximately three hundred permits, many of which had not been adjusted since the 1940s. Kettle Falls District Ranger Don Carney gave Farrell his views of the situation that summer. "We are facing an immediate problem which could run completely out of control over the near term: that of people using government lands as if they owned them privately," he warned. He traced the source to adjacent owners and developers rather than visitors. He suggested that press releases discussing the problem and potential consequences would help, along with publicity surrounding a few notable citations. Some areas might need fencing, while others might have to be closed to grazing. Another improvement, in Carney's view, would be the simplification of the dock permitting process. All in all, "the quality of the water experience people have here will depend increasingly on how we manage our lands." [42] LARO adopted a new fee schedule in July 1977. Farrell managed to reduce the permits to 182 by combining several on a single permit, and revenues increased from $8,600 in 1976 to $10,500 a year later. He continued to work on the issue until he left the park in 1982. [43]

Changes in Policy, 1980s

Special use permit policy came under even greater scrutiny starting in 1981 with the arrival of a new superintendent, Gary J. Kuiper. He was experienced in dealing with trespass and encroachment issues, having started with this during the early 1960s when he was a ranger at Natchez Trace Parkway in Mississippi. "I kind of waded into that and was successful in turning around a tradition of inappropriate use of public lands," remembered Kuiper. "That's kind of followed me my whole career." Turning around the well-established situation at LARO proved to be a challenge for Kuiper and his staff. [4]

Early in 1982, Chief Ranger Charles V. Janda distilled the background and current issues concerning special use permits at LARO. He blamed the dilemma on the Tri-Party Agreement that committed the Park Service to managing the Recreation Zone under a multiple-use concept. He suggested that this management paradox had led to policies with no clearly defined objectives, bringing marginal success and frequently setting untenable precedents. He pointed to several problems and made suggestions for improvement including standardized guidelines and procedures; clearly defined roles; a system to track special use permits and encroachments and to circulate such information among key staff; establishment of goals for resolving encroachments; and an active public relations program that included regular contact with permittees. [45]

|

The presence of private facilities at or near

the shoreline creates the unmistakable impression that public use within

these areas is not invited. In extreme cases, permittees have actually

denied visitors access to Federal lands. . . . Essentially, adjacent

land owners have de facto control of much of Lake Roosevelt's shoreline.

-- LARO Resources Management Plan, 1982 [46] |

The 1982 Resources Management Plan (RMP) showed the influence of both Kuiper and Janda. It, too, pointed to problems stemming from the Tri-Party Agreement that implied that "private, commercial, agricultural and industrial uses are at least on a par with Service developed recreational programs." Forcing the Park Service to assume responsibility for administration of the wide variety of leases and special use permits caused the staff of the 1940s and 1950s to develop land use policies more through innovation and compromise than by strictly following Park Service principles. Most of the encroachment problems could be traced to current permit holders who had built on federal land without detection. Over the years, this had produced enough development along the shoreline to give the impression that much of the lakeshore was privately owned. The RMP admitted that, by 1982, adjacent property owners essentially controlled large areas of Lake Roosevelt waterfront. LARO suggested three possible alternatives for dealing with the complex issue of special use permits and encroachments. The first continued present lax and inconsistent management practices; the second introduced strict and consistent enforcement measures; and the third, the preferred alternative, was a combination of both. Under this approach, the Park Service was to analyze the problem thoroughly, review objectives, and develop policies and guidelines. Managers would be allowed some latitude in dealing with encroachments to mitigate hardships faced by property owners. Good public relations were important to keep the situation from degenerating into adversarial relationships. [47]

Superintendent Gary Kuiper and his staff developed an Encroachment Plan for LARO in 1982. Although all encroachments were considered violations, Kuiper urged his staff to approach those responsible in a neighborly, non-intimidating fashion. "If our objective is legally and morally valid," he wrote, "our methods must be of equal stature and above reproach." He cautioned his staff not to expect an instant turnaround on a situation that had been building for two or three decades. The Encroachment Plan outlined procedures that designated the District Ranger as the key person in the resolution of all encroachments. Other LARO staff, including the Land Management Specialist, Chief Ranger, and Superintendent, were available for advice and assistance but only if requested by the ranger in charge. The Chief Ranger directed the program, reporting to the Superintendent. The plan emphasized written communications to document each encroachment, with all key personnel kept informed. District Rangers were to inventory all encroachments by June 1, documenting new ones. Minor infractions could be resolved immediately, but more complex ones would need investigation. Special use permits could resolve some encroachments, but the plan cautioned against this approach: "An encroachment is, first and foremost, a violation of the law, not a logical extension of a Special Use Permit or cause for its issuance." [48]

The push to regain control of federal lands at LARO was further strengthened with the arrival of Kelly Cash in 1983. He became Assistant Superintendent, bringing to the job his experience as a planner with the former Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in Seattle. Cash immersed himself in the difficult issues of special park uses, writing much of the policy and correspondence during his twelve-year tenure. "It was like pulling teeth," he recalled, "but it had to be done." [49]

In January 1986, LARO held a parkwide staff meeting at Kettle Falls to discuss new guidelines for special use permits. After dividing the permits into various categories of uses, individuals agreed to draft guidelines. They were encouraged to think about what they were trying to achieve as well as what the resource should look like in twenty years. They also agreed that new permits did not have to be handled the same way as existing ones. [50]

LARO adopted a policy in 1987 to use special use permits as leverage to encourage permittees to remove encroachments. This did not involve putting encroachments under permit, as had been done in the case of the Moody cabin and others over the years. Instead, if verbal negotiation with the permittee failed to produce results, the Park Service could apply special conditions to any existing permits in an effort to promote compliance. For instance, LARO could recommend against renewal until the encroachment was removed. Where the permit had already been renewed, the park could shorten the renewal period to ensure compliance. If the permit were not renewed, the encroachment could be removed by LARO, with the owner paying costs or, in the most difficult cases, it could be referred for legal action. Finally, LARO could refuse to issue the permittee any further permits until all encroachments were removed. [51]

Just as LARO was moving to tighten up special uses, the Park Service did the same with the publication in 1986 of the "Special Park Uses Guideline NPS-53." The new policy stated clear limitations on private use of federal lands, "A special park use must not be granted unless the authority for allowing the action can be clearly cited, its need or value is confirmed, and its occurrence has been judged to cause no derogation of the values or purposes for which the park was established, except as directly and specifically provided by law." Derogation involved a judgment call based on the particular park and the context of the park use. It included not just physical resources, but visitor experience as well. The Park Service encouraged phasing out existing activities and uses that conflicted with this policy. The agency knew that permittees would resist the changes, so it stressed the need to keep careful administrative records to support all decisions. Before any controversial termination, park managers needed to assess the performance of the permittee over time, examine the legal/policy implications of both approval and denial of the permit, assess the impacts, and list alternatives that might achieve desired ends. [52]

As LARO personnel moved into action, they sought approval from Reclamation for their new policies. Following an interagency meeting in November 1986 to discuss land management at LARO, Reclamation's Regional Director restated his agency's policy. In general, it did not object to other land uses as long as they did not interfere with the primary purposes of the project. Reclamation did not, however, approve of "private or semiprivate uses" of Reclamation lands unless denial of such use would amount to a hardship, such as with a utility right-of-way. The Bureau had transferred management responsibility to the Park Service, but it still expected coordination of the two agencies on land-use decisions. It deferred to the Park Service on all other management issues. The Park Service Regional Director compared Reclamation policy with NPS-53 and found the two "very compatible." He was relieved, since individuals cited for encroachments often questioned Park Service authority and policy. "As we address these conflicts, it will be beneficial to cite the mutually supportable policies of both our agencies." He promised that the Park Service would work with Reclamation at Lake Roosevelt when developing new land-use guidelines. [53]

During this same time, the Park Service requested permission from Reclamation to keep the fees it collected from special use permits to help offset administrative costs of managing permits and leases at Lake Roosevelt. These expenses had risen steadily with the increase in permits and the complexity of the situation, yet LARO received no funding for this work in its base appropriation and no reimbursement from Reclamation. Instead, the agency used funding designated for both visitor services and resources management to administer permits. The Park Service estimated the costs at $50,000 per year, with revenues from permits and leases totaling approximately $22,000 per year in FY1984-1986. Reclamation agreed in September 1987 to let the Park Service keep the fees to partially offset administrative costs. Within a few months, Gordon D. Boyd, LARO's Chief of Interpretation & Resource Management, did a careful analysis of the costs of administering special use permits. The twelve staffers working part time on permits amounted to 2.11 full-time equivalents for the permanent, full-time employees and .10 full-time equivalents for the temporary rangers. Adding wages, benefits, and support costs, the total came to $66,275 per year. Boyd estimated FY1988 permit fees would total $23,242, leaving $43,033 to come from the Park Base. [54]

Special Park Use Management

Plan

In 1987, Superintendent Kuiper and his staff began drafting a "Special Park Use Management Plan" to bring LARO policies into line with the recently released Servicewide guidelines in NPS-53. The park released the draft for review in February 1989, providing copies to commissioners in the surrounding counties, various user groups, and individuals. LARO staff held public meetings with the Lake Roosevelt Property Owners Association, Lake Roosevelt Development Association, Seven Bays Homeowners Association, Save Our Shorelines Association, three yacht clubs, and two fishing clubs. All meetings gave the Park Service a chance to provide information on the draft plan and offered citizens a chance to comment. LARO also distributed more than one hundred fifty copies of the draft and extended the comment period from March 10 to September 15. Despite this, there were just fifty-six written comments showing opinion roughly split, with twenty-nine in favor of the new plan and twenty-seven opposed. During this review period, LARO placed a moratorium on new applications for special use permits. [55]

LARO's Special Park Use Management Plan laid the groundwork for a total revision of the leases and permits allowing private use of lands within the NRA. The plan stressed the Park Service policy to end all private uses that were either incompatible with public uses or not in the best interest of the public. In addition, Congress had mandated that the Park Service conserve resources to "leave them unimpaired for future generations," and LARO management had determined that most special uses caused impairment. The park saw a conflict between the more than two hundred special use permits and the significantly increased visitation that impacted both resource management and public relations. Given this background, LARO arrived at a management goal: "to protect the natural appearance of the lakeshore and restore the public shoreline to natural open space for use by the general public." [56]

This goal meant a radical change for LARO and its permittees. The plan called for no further special use permits that did not meet the guidelines of NPS-53, along with a phasing out of those existing permits that failed these standards. Only permits deemed compatible would be renewed. Given these tough standards, any improvement that suggested private ownership was scheduled for phase-out, including all boat docks (both private and group), boat houses, gasoline storage tanks, stairways, patios, lawns, landscaping, fences, fireplaces, sheds, and flag poles. In addition, all grazing and agricultural permits would be phased out, the first by 1995 and the second by early 1998. The only special use not targeted was private water-withdrawal systems that would be allowed under permit as long as the facilities were unobtrusive. After all, withdrawal of water for agriculture had always been compatible with Reclamation's project purposes. [57]

|

| Example of stairway encroachment on LARO lands, September 1991. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.PAO). |

To soften the effect of these drastic changes, LARO proposed a phase-out period for all uses scheduled for termination. Although such phasing out did not meet NPS-53 guidelines, the Park Service viewed this as a compromise as well as a way to allow owners to amortize their investment. For instance, following termination of the current permit, all private docks would be extended for one five-year period, ending no later than 1997; any group dock could be extended for two five-year periods, with all terminated by 2002. Lawn permits had a shorter extension of only two years. Many other uses, such as stairways and firepits, were listed as special conditions, due for removal by the end of the first permit extension. The park also recognized that the loss of private docks would put subsequent pressure on public facilities. Special Congressional appropriations, championed by Congressman Tom Foley, resulted in $1.9 million in FY1991 and 1992 to help build six new boat launch ramps and retrofit and expand nine existing ones. These new facilities provided better access than docks during times of lower lake levels. They also partly mitigated the "pending inconvenience in access" for some adjacent landowners. [58]

|

Current special uses constitute a serious

resource management and public relations problem which can only become

more significant as conflicts between recreation users, developers and

adjacent landowners increase in frequency and magnitude. Management

action, under this plan, is designed to resolve the conflict.

The goal of Coulee Dam NRA management is to protect the natural appearance of the lakeshore and restore the public shoreline to natural open space for use by the general public. -- Special Park Use Management Plan, 1990 [59] |

In addition to a total revision of permitted uses, the Special Park Use Management Plan provided for significantly increased fees. Applicants for a new or renewed permit now had to pay a minimum administrative fee of $225, with additional expenses if the permit required an environmental or archaeological assessment. LARO based fees for boat docks on moorage rates at other locations in the West and arrived at a suggested fee of $250 per year. Park Service Deputy Regional Director William Briggle revised the rates, however, to soften the blow. Under the new formula, the owner of a private dock would pay $225 for the first year and $100 each year thereafter. Identical rates applied to individuals using a community dock with multiple ties, with each tie assessed an annual fee. Revised rates for mooring buoys were $175 for the first year and $50 for the next four years. Families with leases on summer cabin sites also had new rates, based on a 1988 appraisal by Reclamation. Sherman Creek sites had an annual fee of $1,050, while lakeside lots at Rickey Point went for $850 and secondary lots for $550. [60]

By 1990, the only industrial use remaining on park land and water was the Boise Cascade lumber mill at Kettle Falls. Despite the decades-old permit for that site, LARO moved to cancel the lease because the industrial use was no longer consistent with the purpose of the NRA. The agency terminated the log storage in the lake, which was no longer used, and started a phase-out of log storage on public lands. Under the plan, the permit would be renewed in 1990 and again in 1995, only if all conditions were met, with operations ending in 2000. Figuring the annual lease fee at 5 percent of the appraised value, LARO raised the fee to $2,838, with an additional $225 administrative fee charged the first year. The mill, located on adjacent private lands, had only a small part of its operations on federally-owned lands. Still, the Park Service met great resistance in its effort to get all mill operations, which no longer needed water access, off federal property. The controversy was eventually resolved through a land exchange completed in November 1996. [61]

As LARO reduced special uses in the park, it also concentrated efforts on controlling encroachments and trespasses. Some problems with adjacent landowners stemmed from years of use, and residents naturally complained when told to remove lawns and other private development on federal lands. These issues formed the basis of a protracted disagreement between the Park Service and the residents of the Riverview Area Association in 1986-1987. In the years since the start of the development in 1959, residents had encroached onto park lands with lawns, sprinklers, a parking area, pumps, and a fire ring. Some of this was a result of legitimate misunderstanding of the property lines, and it was not until Reclamation resurveyed the boundary that many owners realized they were using federal lands. As the group negotiated for a renewal of their special use permit for a dock in 1986, LARO told them that conditions would include reducing the amount of lawn and removing other forms of trespass, including their unpermitted swimming platform and diving board. All of this was part of the park's move to restore shore lands to their natural condition to encourage use by the visiting public. Association members objected to both Park Service actions and logic, claiming that the American public, including LARO visitors, preferred green grass to weeds. They were willing to remove the fire ring and the dock but insisted that all other improvements were for the safety and enjoyment of the public. They warned of appeal, if necessary, through both Park Service and political channels. Superintendent Kuiper was willing to compromise on several points, including a mowed path and a strip of grass in front of the cabins and by the dock. In addition, he offered twelve boat slips and three mooring buoys under special use permit. Despite these concessions, the group appealed up the Park Service chain of command, hiring a lawyer to further their cause. This time, however, the National Park Service Director backed LARO staff. He noted that the compromise lawn area was sufficient and declined the Association's request for further privatization of park lands. Instead of a dock, the community is now served by nine mooring buoys. [62]

LARO staff started to inspect park lands in 1988 to document encroachments and soon realized that the situation was worse than suggested by earlier reports. By the middle of the year, they had found more than five hundred cases and estimated there might be another three hundred. The numbers rose faster than expected, and by late 1989 the park had found 750 trespasses by 145 individuals and expected to locate over 1,500 more by the time the surveys were completed. [63]

The regional office sent an Operations Evaluation Team in 1989 to review encroachment and trespass issues at LARO. One member, impressed with the scope of the problem, commented, "While the more recent efforts have been noble, it may be too little, too late." He found a number of difficulties that contributed to the problems at the park. These included lack of staffing; staff burnout; lack of communication with adjacent county planners; sporadic communications with local realtors; problems in identifying who was responsible for the encroachment; no reporting system; increasing organization of adjacent property owners to lobby politicians; lack of boundary markers in some areas; and difficulty in distinguishing between permitted uses and those in trespass. To help remedy these problems, he recommended that the park institute a "Good Neighbor" policy, getting to know adjacent owners and homeowners associations, realtors, planners, and other county staff to educate them and begin improving relationships. He also suggested mapping all permitted uses and computerizing the data. Finally, he recommended staff increases to include a full-time GS-13 Assistant Superintendent trained as a Realty Specialist, along with three GS-7 seasonal rangers for eight months to do the necessary field work that the regular staff could not assume. [64]

|

| Land encroachment at LARO. House and yard to left of dark line in photo are on private land; deck and garden to right of line are on LARO land. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.PAO). |

LARO had already taken some of the "Good Neighbor" steps recommended during the regional office review to head off problems with adjacent owners and developers. For instance, in 1977 the Stevens County Planning Commission asked Superintendent William Dunmire to comment on a subdivision proposed at Snag Cove. He recommended covenants and restrictions to protect the scenic quality of the shoreline and also suggested that the boundary be clearly marked to prevent inadvertent trespass. In addition, he proposed that the developer notify buyers that they could not develop the lakeshore but they could apply for a community dock. LARO staff commented similarly when a subdivision was proposed for the area near the old Lincoln mill in 1984. They encouraged setbacks of approximately twenty-five feet to prevent lawns and gardens from encroaching on park lands, along with a clear statement to prospective buyers concerning use of federal property. When Gary Kuiper took over as Superintendent, he warned realtors in neighboring towns against advertising properties as having frontage on Lake Roosevelt, a misrepresentation that contributed to encroachments. This problem, however, continued for a number of years. [65]

The Park Service and Reclamation cooperated in 1989 to develop a Trespass Action Plan to help the agencies be consistent in dealing with cases of inappropriate use of federal lands. It included some of the ideas recommended by the regional office. The plan involved basically a three-pronged approach. The first part, the Good Neighbor Initiative, gave priority to marking park boundaries, along with inventorying lands for encroachments, identifying individuals responsible for the trespass, tracking these trespasses and prioritizing them, and finally initiating legal action where needed. The second part of the plan centered around improved communications and education efforts with surrounding landowners, developers, realtors, and community officials as well as special-interest groups. The final part was concerned with the mitigation of encroachments and trespasses, including removal, monitoring, and potential legal action. It also encouraged development of a plan to deal with major encroachments, such as docks, that were abandoned or scheduled for removal by the Park Service. Estimated costs of implementing the plan totaled $163,000 per year for five years, with another $49,000 for administrative costs. Following approval of the plan, Reclamation agreed to mark boundaries and provide realty assistance, while LARO undertook inventory and identification of trespasses, established a public relations program, and initiated mitigation procedures. Costs were to be divided, with totals projected at $100,000 annually. Two seasonal rangers documented several hundred encroachments during 1992 and 1993. [66]

As a last resort, LARO prosecuted violators. Most involved major encroachments, such as Michael Malone's multiple trespasses on park land at Hunter's Creek in 1987. These included a barbed-wire fence running across government land and into the lake; construction of a boat ramp; clearing with a bulldozer and spraying with herbicide; construction of concrete steps and a wooden bridge; fill material bulldozed into the creek; installation of a concrete pad for a caretaker's house; and finally, posting a no trespassing sign on park lands. Although Malone admitted he knew about the encroachments installed by his contractor, and he agreed to cooperate, he ended up appealing his case to the highest levels of the Department of the Interior and Congress. LARO completed its investigation and turned it over to the U.S. Attorney. The case was not resolved until 1992 when Malone signed a pre-trial diversion agreement that stipulated removal of encroachments, site restoration, and payment of $3,373 to cover administrative fees. Malone met the terms of the agreement and LARO staff notified the U.S. Attorney's Office in December 1992 that the Park Service was satisfied with the restoration. [67]

By 1992, the U.S. Attorney advised LARO officials that they should, whenever possible, use pre-trial diversion agreements to resolve disputes, thus avoiding court proceedings. As in the Malone case, these required that the encroachments be removed and the area restored to Park Service approval, along with a fine to compensate the agency for costs of the investigation and restoration. At least two other national park units had established special donation accounts to accept court-ordered restitution, enabling the park to then use the money for operational expenses. LARO established just such an account to take advantage of several cases involving sizeable fines. The park was able to resolve most encroachments through informal negotiations with the adjacent landowners, avoiding the need to take the cases to court. Of fifty people contacted by early 1993, all but six agreed to remove the trespass; those refusing faced legal action. Another fifty people reached the following year complied with the Park Service request to remove encroachments. [68]

Reaction to the Special Park Use Management

Plan

Given all the proposed changes, public relations played an important part for all sides in the special use campaign at LARO. Kuiper and his staff chose their words carefully when they defined special uses as "privatization of public lands," suggesting that users were taking something for themselves that really belonged to everyone. "It was very effective to use that," remembered Kuiper. In addition, they worked to educate those whose support they needed. They first had to explain the complex situation at LARO to the regional office so staff there could respond when confronted with the issue. To further this end, they hosted a Superintendents' conference at the park and took attendees out on Lake Roosevelt in houseboats. As they cruised along the shoreline, they asked the visitors to tell them where the boundary was. With development, docks, and associated encroachments, the line was hazy — but the scope of the problem was clear. LARO personnel took the same trip in April 1991 with staff from various congressional offices to acquaint them with the land management issues facing the Park Service at Lake Roosevelt. Rep. Tom Foley backed LARO staff as they worked to implement the federal guidelines handed down through NPS-53. That summer, Foley met with a group of ranchers, adjacent property owners, and county commissioners, all of whom wanted him to help them stop the implementation of the Special Park Use Management Plan. LARO officials briefed Foley before the meeting. After listening to his constituents, he still backed the LARO plan with its long phase-out period. "From that day on, we charged ahead," said Kuiper. [69]

Despite LARO's efforts at public relations, changes in the system of special use permits and reduction of encroachments generated complaints that have continued for years. Some alleged that local Park Service management was unresponsive to the public and allowed no input on its Special Park Use Management Plan. Others suggested that LARO was enforcing more severe restrictions than mandated by NPS-53. One person maintained that Park Service policy did not distinguish among places designated as wilderness, national parks, or national recreation areas, applying the same restrictions to all when this was inappropriate for the use. Permittees, of course, had their own complaints that included restrictions on their lifestyles, limited access to the lake front, and increasing congestion at public launching facilities. LARO officials responded to complaints with letters and press releases that reiterated their theme of returning public lands to public uses, away from private uses that benefit just a select few. [70]

| Just as the Park Service was tightening its management of special use permits, the Colville Confederated Tribes took similar action. A group called the San Poil Bay Improvement Association approached Reclamation in 1991 about obtaining a ninety-nine-year lease on some land previously used by its members, including a boat launch, docks, and assorted structures. The Bureau sent them to the CCT, who had taken over all such permits under the 1990 Multi-Party Agreement. Because the tribes were still developing policies, they were willing to allow only one dock, previously permitted by the Corps, for one year only. But the Director of the Parks and Recreation Department noted that none of the other facilities had permits, including several other docks, log booms, bridge, outhouse, and picnic table. Because the shore lands were public, the tribes did not allow structures on these lands that "give the appearance that the site is in private ownership." The Association was given until the end of June 1992 to remove all such structures. After some negotiations, the CCT relented slightly and allowed the group to have a permit until the end of March 1993, provided that the public was allowed to use the facilities in the interim. [72] |

Throughout the years of controversy, LARO management had its vocal supporters as well, individuals who wrote letters and spoke at public meetings. When District Ranger Steve Castro-Shrader spoke to a large crowd at the Seven Bays Homeowners Association in 1987, discussing encroachments and restrictions on off-road vehicles, he did not hear any negative comments or questions. He found the people supportive of the Park Service in its efforts to deal with uses that had gotten out of control. Supporters understood LARO's catch-phrase about privatization of public lands. For instance, one man explained that private docks force the public to look for other beaches. "That's essentially turning public property into private property by intimidation," he suggested. Some wanted LARO to enforce NPS-53 more strictly, suggesting that docks should be terminated in no more than three years instead of the twelve year phase-out period. When compared to fees of up to $1,200 per year for a private boat slip rental, Park Service charges were seen as too lenient. Finally, a number of individuals wrote to their congressional delegation to voice support for local LARO staff and their work with enforcement of permits and general management of the park. [71]

Grazing and agricultural permits were among the first to be scheduled for termination, with no additional extensions proposed beyond the original 1995 and 1998 dates. In 1991, LARO still managed thirteen grazing permits that covered 290 cattle, 7 horses, and 27 sheep. The livestock left waste on beaches and campgrounds, posing threats to both the water supply and visitor enjoyment. Fees generated by these permits brought in less than $1,500. Ranchers who leased the NRA shore lands felt threatened by the Park Service's move to terminate grazing because their leases included access to water, and they appealed to their congressional delegation. During at least two meetings with LARO personnel in 1991, cattlemen expressed their concerns and the Park Service reiterated its policy of allowing water withdrawals from the lake for agricultural purposes. They also discussed fencing as a potential solution. LARO had already enclosed the area around Plum Point, leaving a corridor to provide stock access to the lake, and the group talked about fencing other sensitive areas such as Hunters and Hawk Creek. The park agreed to appoint a committee to develop a solution to the grazing issue, but it held to its original five-year phase-out. The following year Superintendent Kuiper asked Washington Senator Slade Gorton for a funding increase to help resolve the problem with cattle. He requested a multi-year $100,000 base funding increase for fencing to reduce conflicts between livestock and other uses of the reservoir area; Congress did not approve this increase, however. [73]

|

| LARO crew installing a cattle guard on east bank of Sanpoil Bay, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

LARO extended grazing leases until March 1997. Park officials, however, remained concerned about the repercussions, so several months before the termination date they began "preparation for what . . . [would] most likely be the next round of resistance by special interests." This included working on position papers to ensure that park personnel maintained consistent responses to the issue. They also began to look in depth into the issues surrounding grazing, such as who was responsible for fencing, what were the legal rights to public water sources, what options did the permittee have if his lease were terminated, and what would the economic impact be on the permittees. They found that there were still ten special use permits covering more than two hundred cattle, four horses, four llamas, and twenty-one sheep. Federal agencies were exempt from the open-range law, meaning that it was the responsibility of adjacent landowners to fence the boundary. LARO Ranger Gig LeBret noted that, at least in the Gifford area, the park had done no fencing since 1992 because of lack of funding and changes in priorities. He had talked about fencing with some landowners, "but when word got out we were going to fence the public out, management let it die." Permittees seemed to be willing to hold out to see what would happen if they refused to give up their grazing uses. [74]

A few weeks before the expiration of grazing permits, LARO Superintendent Vaughn Baker wrote to all permittees to inform them of the imminent, but well-known, termination of their permits. He explained that LARO could not legally allow grazing on park lands, but he understood the ranchers' need to access water. The public disliked livestock in recreational areas; the Park Service worried about damage to riparian areas and water quality; and ranchers were concerned about the cost of fencing. Baker asked in his letter, "What can we do, working together, to address these issues and concerns?" He suggested such possibilities as developing water sources away from the lake, installing systems to withdraw water from the lake, and cooperating on fencing. "We'd like to explore these with you in lieu of initiating trespass actions after the permits expire," he offered. At least one rancher responded to Baker's overture, agreeing to discuss possibilities later that spring. [75]

The grazing issue was not immediately resolved, and LARO personnel continued to work with ranchers to find appropriate solutions. Park officials were especially concerned with the possibility that, without the permits, some ranchers might be forced to sell out to developers, a prospect that would change the rural character of the lands surrounding Lake Roosevelt. In late February 1998, LARO considered giving the remaining permittees Interim Letters of Authorization to continue use of public lands for no longer than two years, allowing them additional time to find alternative sources of water. None of the permittees requested such letters, however. [76]

The congressional delegation maintained its interest in the grazing situation. While both the Senate and House removed a requirement that LARO renew grazing leases, the Congressional Committees on Appropriations were "deeply concerned" about the Park Service's change in its historical grazing policy in the park. The committees directed LARO to submit a report by July 1, 2000, on the history of grazing and all other uses of lands now administered by LARO since 1935 under the Columbia Basin Act and since 1946 under the Tri-Party Agreement. In addition, the committees directed that beneficial uses at LARO, including grazing, may remain under permit until the Park Service determines that "the permitted facility or activity is in conflict with a new or expanded concession facility." If such a conflict occurs, LARO may terminate the permit. [77]

Fees increased for all special park uses, including the Hellgate Youth Camp located between Jones Bay and Hanson Harbor. The area Boy Scouts, through a special use permit issued to the Wilbur Amateur Athletic Association, had established a camp on forty-three acres of park land in the late 1940s. The annual fee initially was $25 but later increased to $50. LARO South District Ranger Gil Goodrich met with local scout officials to discuss the camp early in 1991. He indicated that the Association might need to give up part of the forty-three acres, and some at the meeting suggested they could reduce to ten acres as long as they could keep use of the beach, road, and surrounding area for scout activities. A while later the scout committee reconsidered and decided they were unwilling to give up any of their camp and would fight to keep it all. Goodrich initially assessed the group $33 per acre (or $1,419), plus a $100 administration fee and $25 annual billing fee, but he later told them he had used incorrect figures and the real cost would be based on $110 per acre, or a 5 percent return on the appraised value of $2,200 per acre. This brought the total to $4,730 plus $125 in fees, a considerable increase from the previous $50 per year. [78]