|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 4:

Agreements and Disagreements: From Tri-Party Agreement to Multi-Party Agreement

From the beginning, National Park Service administration at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO) has been entwined with the interests of the United States Bureau of Reclamation, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and two federally-recognized tribes — the Colville Confederated Tribes and the Spokane Tribe of Indians. The resulting complex jurisdictional situation has changed considerably over the years and continues to evolve today. Sometimes the three agencies, all siblings within the Department of the Interior, have worked cooperatively toward common goals while at other times they have squabbled like a dysfunctional family. The addition of the tribal voices, on equal footing with the three agencies, has altered the balance, and all five parties have been adjusting to new roles over the past decade.

The most complex administrative relationship at LARO is that between the Park Service and the two tribes. Historians Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek have noted that Park Service-Indian relations nationwide generally fall into four stages: "(1) unilateral appropriation of recreational land by the government; (2) an end to land-taking but a continued federal neglect of tribal needs, cultures, and treaties; (3) Indian resistance, leading to aggressive pursuit of tribal interests; and (4) a new NPS commitment to cross-cultural integrity and cooperation." [1] There are variations in this pattern at LARO, of course; for instance, although Reclamation purchased Indian lands for reservoir purposes, it soon turned these lands over to the Park Service to administer for recreation. Despite these variations, the same general stages appear to hold true, from acquisition of Indian lands for Grand Coulee Dam and its reservoir through the 1990 Lake Roosevelt Cooperative Management Agreement (or Multi-Party Agreement) to the present.

Indians had accumulated numerous grievances well before their lands were condemned for the Grand Coulee project. Their losses began decades earlier with the establishment of reservations and subsequent forced land cessions. Federal policies around the turn of the century encouraged assimilation of Indians into mainstream non-Indian culture. For instance, Indian children were sent to boarding schools in an effort to suppress traditional Indian culture. Similarly, allotment of reservation lands was supposed to encourage Indians to become farmers; it also freed up "excess" land for non-Indian settlement.

During the 1920s, Indian poverty caught the attention of some whites and spawned a number of organizations interested in Indian welfare. Concurrent with the interest of private groups, the federal government began a slow reversal of its assimilation policies. Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work designated the independent Institute of Government Research to report on reservation conditions and federal policy. The group published its report, "The Problem of Indian Administration," known simply as the Meriam Report, in 1928 and set the stage for future reforms. Evidence of desperate health and economic conditions suggested that established Indian policy had done little to create self-sufficient citizens. To counter this dismal situation, the Meriam Report offered ideas to improve education and health programs. The authors also recommended a whole different approach to native people, one that showed respect and understanding of their Indian culture. These conclusions and suggestions repeated those made by other reform groups. Change began with President Herbert Hoover's appointees in the Department of the Interior and accelerated when John Collier was appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1933. [2]

The most important legislation to come out of this period was the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act. It called for tribal elections to either accept or reject the requirements to write a tribal constitution and establish self-government. For those tribes that voted to accept these, the act called for an end to land allotment and provided for additional purchases of lands to replace some of those lost under the Dawes Act. In addition, any lands that had not been allotted were to be returned to the tribal governments. The IRA also established a revolving loan fund for community development, provided educational loans for Indian students, and allowed Indian preference for jobs in the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA). [3]

Although two-thirds of the tribes nationwide voted to accept the provisions of the IRA, not all tribes were pleased with the choice. Among these were both the Colville and Spokane tribes. The Colvilles rejected the IRA in an election in April 1935, with 421 voting in favor and 562 against. Tribal members also rejected a constitution in June 1936, but after revisions, those who came to the polls in February 1938 voted heavily in favor. This established the Colville Business Council with fourteen members from four districts. In addition, it gathered the eleven separate bands of the reservation and renamed them the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT). The Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI) also voted down the IRA but did not approve its tribal constitution until May 1951. [4]

Loss of Lands to Grand Coulee Dam

Project

The Indian Reorganization Act came too late to help the CCT or STI in their dealings with the government during construction of Grand Coulee Dam. With the Colville Business Council just recently organized and the Spokane Tribe still without any officially recognized form of tribal government, neither was in a strong position when Reclamation began the massive Columbia Basin Irrigation Project. Instead, they relied on the OIA to look out for their interests. At the start of dam construction in July 1933, Harvey K. Meyer, Superintendent of the Colville Indian Agency, warned OIA officials that the Indians claimed half of the river. After thorough study, Assistant Commissioner William Zimmerman, Jr., agreed, and he promised that the Federal Power Commission would pay careful attention to protecting Indian rights. He asked Meyer to keep him "advised of any important development affecting the Indians' interest." [5] Later that fall, Frank R. McNinch, Chairman of the Federal Power Commission, asked for information on how the project at Grand Coulee would affect Colville and Spokane Indian rights. Zimmerman responded that the enormity of the project made it difficult to advise at that point, but he described the potential power production from the dam and concluded that it "could bear a reasonable annual rental . . . for the Indians' land and water rights involved." According to Zimmerman, the Solicitor's Office stated that Reclamation would take care of tribal interests. [6]

Reclamation tried to get a handle on the monetary value of Indian losses. In 1934, L. M. Holt, Supervising Engineer in Salt Lake City, made an initial estimate of the value of Indian lands and timber. He also recognized the importance of salmon to the Colville Tribe and noted that while the value of the annual catch was difficult to determine, $15,000 per year seemed like "the proper figure" to use. More importantly, he acknowledged only the Colville Indians' rights to a share of the undeveloped power, estimating the compensation due at $1 per horsepower, or a total one-time payment of $345,000. He claimed that the amount of water needed for power generation that originated on both reservations was negligible when compared to the total flow of the Columbia. In addition, the dam's location on the north bank was on a white homestead rather than Indian land. He figured that annual payments to the Colville Tribe of $34,419 and just $690 to the Spokane Tribe would compensate them both fairly for the loss of lands and timber and would further compensate the Colville Tribe for their loss of salmon and undeveloped water power. Reclamation, however, found by 1937 that it was busy with other urgent matters, and concern for Indian rights to power revenue and compensation for loss of the salmon runs fell by the wayside. The Indians remembered this promise, though, and in January 1941 Mr. Adolph reminded the Colville Business Council saying, "One of our Indians asked Mr. Wheeler about our royalty. Mr. Wheeler stated that we would be entitled to royalty." [7] Despite these promises, the settlement would take decades to resolve.

Reclamation and the OIA worked together to acquire Indian lands needed for the project. During 1937, the General Land Office surveyed Colville Indian allotments and tribal lands along the projected high-water line. The following year, Reclamation drafted legislation that allowed it to obtain rights-of-way across Indian lands. With the legislation evidently delayed and waters starting to rise behind the dam, Reclamation grew anxious to resolve the issue. It negotiated a memorandum of understanding with the OIA, signed on April 6, 1939, to purchase Indian lands. The MOU noted that some of these lands had already been inundated and the water was approaching others, necessitating the immediate purchase of all Indian interests in these tracts. It stipulated that Reclamation's appraisals be adopted over those of the OIA since they were more favorable to the Indians. Other interbureau agreements during this period covered additional lands as well as relocation of utility lines and roads. [8]

Payment was slow in coming, however, causing worry for Louis Balsam, who served at the Colville Indian Agency as Field Representative in Charge. He claimed that each day of delay caused genuine harm to many tribal members, and he urged prompt payments so that people could afford to relocate at upper elevations. Most of the condemned lands were used for agriculture and grazing and thus were important for subsistence, so Balsam recommended that both commissioners of Reclamation and Indian Affairs consider the annual crop cycle when acquiring lands. "The taking of these lands for clearing, which is absolutely necessary, is causing unrest among the Indians," he wrote. "Any delay now in paying for these lands means that starvation conditions may result during the 1940 crop year." He urged prompt settlement and noted Reclamation had been making payments to fee title holders, most of whom were non-Indians, for more than four years. Doing the same for tribal allottees would help "allay understandable charges that Indians have not been accorded equality in these right of way matters." [9]

Act of June 29, 1940

With waters rising rapidly, Congress finally enacted legislation, drafted by Reclamation and the OIA, to acquire Indian lands for the Grand Coulee project. A few months prior to passage, John C. Page, Commissioner of Reclamation, had suggested wording to tighten up the language concerning Indian rights. This limitation was needed, he explained, to help the Bureau "sponsor the greatest possible development of reservoirs" by working with other federal agencies. He believed that the limits of any reserved rights had to be clearly defined before the agencies could effectively plan their work. [10] The Act of June 29, 1940 (Acquisition of Indian Lands for Grand Coulee Dam, 54 Stat.703), gave the United States "all the right, title, and interest of the Indians in and to the tribal and allotted lands within the Spokane and Colville Reservations," up to 1,310-foot elevation, except at the Klaxta townsite where the government was allowed to take lands above that line. In addition, the act gave the government the right to take additional reservation lands "from time to time" as needed for utilities and roads in connection with the Grand Coulee project. The Secretary of the Interior was allowed to determine "just and equitable compensation," with payments for tribal lands being transferred to the appropriate tribal account. Compensation due to individual owners was transferred to the Superintendent of the Colville Agency to credit to the person's account. The Secretary of the Interior was then permitted to use these funds to purchase other lands and improvements or move existing improvements to a new site to benefit the allottee. [11]

Section 1 of the 1940 Act contained a key paragraph that has generated more confusion, controversy, and pages of legal opinion than probably any other document pertaining to the Grand Coulee project. It states,

The Secretary of the Interior, in lieu of reserving rights of hunting, fishing, and boating to the Indians in the areas granted under this Act, shall set aside approximately one-quarter of the entire reservoir area for the paramount use of the Indians of the Spokane and Colville Reservations for hunting, fishing, and boating purposes, which rights shall be subject only to such reasonable regulations as the Secretary may prescribe for the protection and conservation of fish and wildlife: Provided, That the exercise of the Indians' rights shall not interfere with project operations. The Secretary shall also, where necessary, grant to the Indians reasonable rights of access to such area or areas across any project lands. [12]

The Committee on Problem No. 26, set up to provide guidance for the recreational development of the reservoir area, wrestled with the implications of this paragraph. What area was included in "approximately one-quarter of the entire reservoir"? What did "paramount use" mean? What rights were Indians giving up in exchange for one-quarter of the reservoir? "Isn't the setting aside of one-fourth of the entire reservoir area for the paramount use of the Indians going to create some serious difficulties?" asked one committee member. [13] The problems became immediately apparent and during the next year, state and federal officials planning the new recreation area realized they needed help, particularly from the Indians. Unable to obtain advice from the tribes, a subcommittee appointed to clarify the 1940 Act concluded that the area reserved for Indians applied to the water only and recommended that this be adjacent to reservation lands. It further determined that "paramount" was not "exclusive," so non-Indians could fish in an area designated for the paramount use of the Indians as long as they had a special license like that needed for fishing on reservation lands. Details for administration of the area set aside for the Indians would be worked out between the OIA and the agency chosen to administer recreation in the new reservoir. [14]

Across the lake, the Colville Business Council tried to make sense of the same issues. Mr. Adolph, a Council member, noted that Indians had not been consulted prior to either construction of the dam or passage of the Act of June 29, 1940. "And still today, we were not asked what did we want," he reminded the Council. "The 1/4 that was offered to us, there is a question as to where it may be taken. Therefore, I say let us take it slowly and consider it thoroughly as far as our lake rights are concerned." Following questions from other Council members, Colville Agency Superintendent Robertson said that one-quarter of the total reservoir area would amount to approximately 22,255 acres, yet if they used the reservation boundary of the middle of the river, the Indians would get over 33,600, an increase of more than 11,000 acres. Mr. Lemery picked up on this point. Remembering the loss of the north half of the reservation, he challenged fellow Council members: "We Indians are dumb and I guess we got to admit it," he said. "If you consent to concede these 11,600 acres, you are conceding your right to the boundary in the middle of the river. I think you should stand on your ground, and if you have to bring a suit, you should do it." Carthon Patrie, OIA Acting Regional Forester with the Colville Indian Agency, agreed that the Council did not need to rush this matter but he applied some pressure by suggesting that the sooner they could tell the Secretary what they wanted, the more favorable response they would get. He thought they could probably get the reservoir area bordering the reservations out to the thread of the river. By the end of the meeting, the Council refused to accept the terms of the Act of June 29, 1940, and instead chose "to retain all rights, powers and privileges heretofore held by them by virtue of previous treaties and/or agreements between said Indians and the United States Government." [15]

The Spokane Indians reacted with similar concerns. At a tribal council meeting held in January 1941, Superintendent Robertson gave figures for one-quarter of the reservoir area but explained that if the Indians got all of the Spokane River and half of the Columbia River where they bordered reservations, they would get 40,480 acres. He told them that the Secretary of the Interior had authority to set this much land aside for the tribes, but he wanted to hear views from the Indians. After much discussion, the Council passed a resolution "that we should have all the rights and full control of the entire Columbia Basin Lake, to the 1310 level, where it borders on the Spokane reservation, as long as these rights do not interfer [sic] with the operation of the Grand Coulee project; provided that the acceptance of this area does not jeopardize any claims the Spokane Indians may have because of losses sustained by the tribe." [16] Late in 1941, a delegation of members from both the CCT and STI went to Washington, D.C., to protest the limitation of their rights directly to the OIA. The outcome of this trip is unknown. [17]

Local OIA officials reiterated the Indians' statements and noted that both tribes were more concerned about their rights than the amount of land. They recognized the great potential for both commercial and recreational development of the new reservoir and they wanted to be able to participate. There was still great resentment on the reservations over the way land acquisition had been handled, and Superintendent F. A. Gross warned, "There is far more at stake than the hunting, fishing, and boating privileges interpreted in the strict sense of the meaning of these words." He went on to make several farsighted recommendations, many of which were finally embodied in the 1990 Multi-Party Agreement. These included Indian rights in an area of more than 40,000 acres; full control, including licensing, over activities and concessions for fishing, hunting, and boating between the 1,310 line and the thread of the Columbia and on the entire Spokane River; a deciding vote on decisions to allow commercial, business, grazing, and other uses on the freeboard lands adjoining their reservations; exemption from federal and state fishing regulations; and finally, steps to prevent pollution of the reservoir. [18]

Interagency Agreement

In addition to working through the implications of the 1940 act, many of the same people were working on a memorandum of agreement for planning, development, and administration of recreation in the reservoir area. Both Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes and National Park Service Director Newton B. Drury had approved negotiations among the Park Service, Reclamation, and OIA. Indeed, the results were a foregone conclusion, and the announcement that the Park Service would soon be taking over jurisdiction of the reservoir was released nine days before the agreement was drafted. The agency relied heavily on its experience at Boulder Dam National Recreation Area, and Boulder Superintendent Guy D. Edwards played a key role in producing the agreement. Edwards arrived a week early to meet with Claude E. Greider, State Supervisor, and Raymond E. Hoyt, Chief of the Recreation Planning Division. Greider and Hoyt had written a rough draft based on the interbureau agreement used at Boulder Dam. They were joined by Charles L. Gable, Chief of Park Operators Division, and the four men refined the draft to eliminate items that had not worked well at Boulder Dam. Edwards and Greider then drove to Coulee Dam to represent the Park Service at the meeting to formally draft the interbureau agreement. [19]

Attending the meeting on September 25-26, 1941, were F. A. Gross, Superintendent of the Colville Reservation; Carthon R. Patrie, OIA Regional Forester; Melvin L. Robertson, Colville Indian Agency; L. N. Runnels, Colville Business Council; Claude E. Greider, State Supervisor for the Park Service; Guy B. Edwards, Superintendent at Boulder Dam NRA; Frank A. Banks, Reclamation Supervising Engineer; Philip R. Nalder, Reclamation Associate Engineer; and the Land Clerk from the Colville Indian Agency. Edwards warmed up the group with a presentation on Boulder Dam NRA, discussing its history, development, and administration. Greider then took over and presented the agreement. Discussion proceeded paragraph by paragraph, and the group referred as needed to both the MOA for Boulder Dam NRA, approved on October 13, 1936, and the Cooperative Agreement between the OIA and the Park Service concerning the Hualpai Indian Reservation, approved November 11, 1937. [20]

Although they made few changes in the draft agreement during two days of negotiations, each of the three agencies was able to present its views. Reclamation was concerned about its potential liability for injuries or damages due to landslides, so a special clause excluding them from damage suits was inserted into the agreement. The OIA remained concerned about Indian rights and insisted on having the authority to approve any leases or permits for use of the freeboard lands adjoining the reservations. In addition, it wanted to ensure that fees from licenses, permits, and leases for hunting, fishing, and boating in the area were used to benefit Indians. The Park Service balked, however, at the OIA's request to assume total jurisdiction over the Indian lands acquired under the 1940 act and insisted on administering all the lands as the only way to implement Park Service objectives. The agency further argued that a strict interpretation of the 1940 act gave Indians one-quarter of the water surface and only a "reasonable right of ingress and egress across the strip of land between the water surface and the 1310 line." At the conclusion of the meeting, a draft MOA was in place and endorsed by all attendees. [21]

This draft agreement never went into effect because Park Service Director Drury wanted to wait until detailed studies of the recreation area were completed and the agency had resolved the question of the area's national significance. The Director received a copy of the document within a week of its signing in September 1941, along with a memo from the Regional Director who stressed the importance of securing adequate funding to administer the new area before signing the agreement. Formal agreement on management of the recreation area remained in limbo until Reclamation and the Park Service signed a memorandum of agreement on July 22, 1942, that assigned planning and administration of the area to the Park Service. This was renewed annually through 1946. [22]

1945 Solicitor's Opinion

The question of Indian rights under the Act of June 29, 1940 (Acquisition of Indian Lands for Grand Coulee Dam), continued to concern the agencies working in the newly formed reservoir area. There were calls for a Solicitor's opinion as early as September 1941 when Leroy D. Arnold, OIA Director of Forestry, suggested that such a decision was needed "to obviate any possible unpleasant misunderstandings or disagreements later on." [23] Two years later, Walter V. Woehlke, with the OIA in Chicago, urged the Secretary to define Indian rights soon and went on to offer his interpretation of their paramount rights. These included the right to hunt and fish, without license fees, within the exterior boundaries of their reservations; the right to build and operate docking facilities and rent boats, all without license fees; and the right to use shore lands to water stock. In addition, he urged that the OIA be given jurisdiction over all the freeboard land within reservation boundaries. [24]

Predictably, both the Park Service and Reclamation objected to Woehlke's ideas, particularly the suggestion that the OIA manage reservation shore lands. Greider stressed the need for a single agency to maintain full administrative responsibility throughout the reservoir area, and he claimed that the public interest would not be served by Woehlke's plan to give Indians exclusive rights along the shore. "Undoubtedly, any qualified agency responsible for the administration of the area as a whole could amply provide for all legitimate interests of the Indians," wrote Greider, "and accomplish it in a manner that would not jeopardize certain esthetic, recreational, or other values which should be preserved." [25] Frank A. Banks agreed and added, "I am somewhat concerned because of the change in attitude of the Indian Service officials." [26]

The controversy and bickering ended, at least for a while, with the Solicitor's Opinion of December 29, 1945. Solicitor Warner G. Gardner did not resolve all issues and he left key decisions to the Secretary of the Interior, but he did lay the groundwork for nearly thirty years of jurisdiction at Lake Roosevelt. According to his opinion, the one-quarter of the reservoir area to be set aside for the Indians could include freeboard lands as well as water area, if the Secretary wished. Specific areas had to be allocated to the tribes, either one area to be shared or two separate areas; Gardner suggested that the one-quarter area be divided according to population, with 75 percent going to the CCT and 25 percent to the STI. Furthermore, these lands should be adjacent to or near reservation lands to ensure rights of access to the reservoir. "Other things being equal, this means that they should be located along the former shoreline of the Indian lands," wrote Gardner. The rights of ingress and egress across the freeboard lands should be proportionate with the intended use of the Indians' part of the reservoir. For instance, tribal members would be allowed to build a reasonable number of docks for their boating operations and could build other structures to use in hunting and fishing. On the question of rights, Gardner ruled that "the special rights granted to the Indians under the act were themselves obviously deemed to be a form of compensation for the riparian rights of the Indians for which no separate compensation had been made." While these were not exclusive rights, the Secretary had the power "to make the Indian rights exclusive where necessary to insure the realization of their privileges." Gardner refused to decide whether Indians had the right to grant licenses to others, but he did rule that they should not be charged fees for hunting, fishing, or boating and would be subject only to reasonable regulations to help protect and conserve wildlife. [27]

Tri-Party Agreement

The uncertainty that had clouded jurisdictional issues for several years dissipated immediately, and federal agencies revived their work on a cooperative agreement. Park Service Director Drury sent a copy of the Solicitor's opinion to Regional Director Owen A. Tomlinson asking for his opinion on areas to be set aside for paramount use of the Indians. Although it was primarily the responsibility of Reclamation and the OIA to delineate these areas, Drury suggested that it would be good for the Park Service to be involved in these discussions. He also urged Tomlinson to revise the draft agreement of September 26, 1941, and have it reviewed by the other agencies. If necessary, the Park Service could negotiate separate agreements with Reclamation and the OIA. [28]

Banks pushed for a commitment from the Park Service, causing it to pull back temporarily. Greider and Raymond E. Hoyt, Regional Chief, Recreation Study Division, had a meeting with Banks on February 16, 1946. When they arrived, they found that not only had he invited Reclamation and OIA officials, but he also expected Hoyt to work out the interbureau agreement so that the Park Service could take over management of the recreation area on July 1st. Both Hoyt and Greider made it clear that they were not aware of these plans and furthermore, they had no authority to commit the Park Service to this. Banks, in turn, was unhappy when he found out that the agency had not budgeted any funds to cover the costs of administering the area in FY1947. Despite these disagreements, the federal representatives reached consensus that one agency should have administrative responsibility for the entire area, including commercial operations. The only exception to this was that the OIA would retain control of agricultural and grazing permits in the Indian Zones. The points discussed that day formed the basis for the eventual agreement. Banks scheduled another meeting for the following month, and Park Service officials realized he wanted action. "The attitude of the Bureau people was one of wishing to be relieved of all administrative responsibility above the dam," noted Hoyt. "We feel from their remarks that they will insist that the National Park Service assume the entire responsibility." [29]

Negotiations continued, and on April 8, 1946, twenty-three people met at Coulee Dam to prepare a final draft of the interbureau agreement, including Supervising Engineer Frank A. Banks, Right-of-Way Engineer Thoralf Torkelson, and Regional Counsel H. Stinson for Reclamation; Herbert Maier, Raymond E. Hoyt, George Collins, and Claude E. Greider for the Park Service; and the superintendents of the Colville and Spokane reservations, other OIA officials, and various members of the tribal councils representing Indian interests. Using a memo from Hillory Tolson as a guide, Maier was pleased to report that seven hours of negotiations produced an agreement that incorporated nearly all of the Park Service proposals. After considerable discussion of a name, the delegates agreed on Coulee Dam Recreational Area. A more difficult point involved funding. Banks argued that Reclamation should not have to fund the work since the Park Service was responsible for recreation development and administration. Maier countered that the agency could not request funding for developing and administering an area that was not part of the National Park System. Banks conceded this point, but Maier noted, "It is my feeling that Mr. Banks acquiesced only with the thought in mind that when he transmits the draft to the Commissioner he will suggest further consideration of this item before final submission to the Secretary." [30]

The OIA continued to have some reservations about the agreement. The agency insisted that it be designated to issue permits and administer log dumping operations within the Indian Zones, after consultation with the Park Service. More importantly, Acting Commissioner John McGue maintained that since Indian rights had not yet been defined, he hesitated to sign a document that might be viewed later as a departmental interpretation of these rights. Until the Secretary defined these rights, McGue wanted the agreement to include "a specific provision to the effect that nothing therein contained shall be construed as a waiver of any rights the Indians may have." [31] This statement was included in the final agreement.

Both tribal councils passed resolutions approving the April 1946 draft MOA, but they also voiced concern. In fact, the Colville Business Council passed a second resolution the same day asking that Indians of both reservations be allowed to hunt and fish within the Indian Zones without being charged for a license. In addition, they wanted access to, and the right to build and operate, docking facilities within their zones, as well as the right to rent and operate boats without paying any fees. If their paramount interests were later found to be in jeopardy, they requested that the Secretary set aside all or part of the Indian Zones for their exclusive use. [32]

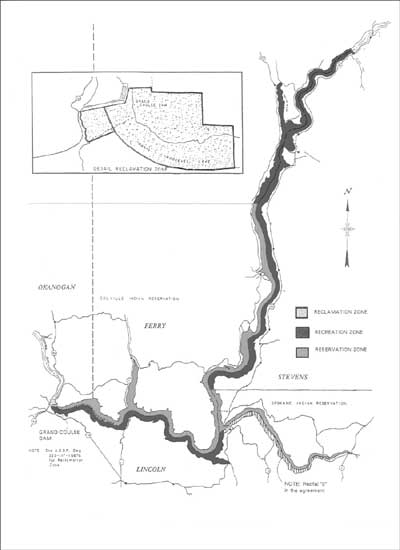

The final MOA, known as the Tri-Party Agreement, was signed on December 18, 1946. It divided the reservoir area into three zones: Reclamation, Recreation, and Indian. The Bureau retained jurisdiction over activities in the Reclamation Zone, including recreation, although the agency was to consult with the Park Service on development of any recreational facilities there. The OIA had responsibility for both the Colville and Spokane Indian Zones, including issuing agriculture, grazing, and log dump permits; fire prevention; and construction and maintenance, in consultation with the Park Service, of any structures needed in conjunction with Indians' paramount rights. The OIA also agreed to provide the Park Service with any help needed in its relations with individual Indians at the new recreation area. [33]

A large portion of the agreement spelled out Park Service duties in the new recreation area. One of the primary functions, of course, was developing and implementing plans for facilities throughout the recreation area. In addition, the Park Service agreed to consult with the OIA in locating and protecting potential recreation sites in the Indian Zones. The agency was also directed to establish policies covering uses of all the land in the recreation area, except for agriculture and grazing in the Indian Zones and special hunting, fishing, and boating rights of Indians. The Park Service took responsibility for issuing and administering permits for special uses, including industrial and recreational, for all the land in the recreation area, and grazing and agricultural uses for lands outside the Indian Zones. The agreement also designated the Park Service as the agency to promulgate rules and regulations governing public uses and protection of resources. Finally, the Park Service agreed to advise both Reclamation and the OIA in recreation matters in their respective zones. [34]

While the federal agencies were still fine-tuning their final agreement at Lake Roosevelt, Congress passed a law that added legitimacy to Park Service administration of the recreation area. Public Law 633, passed August 7, 1946, authorized Park Service appropriations for "Administration, protection, improvement, and maintenance of areas, under the jurisdiction of other agencies of the Government, devoted to recreational use pursuant to cooperative agreements." [35] The Secretary of the Interior issued a statement in July 1947 on the Department's policy for recreation development and administration at Reclamation reservoirs. The Park Service would assist Reclamation on a reimbursable basis to develop preliminary plans for recreational facilities at reservoir areas. As part of this work, the Park Service would submit estimates of construction costs to Reclamation to be included in the annual costs of reservoir construction. If funded by Congress, the Park Service would agree to build these recreational facilities. This information left both Greider and Banks scrambling to determine how it applied to Coulee Dam Recreational Area. Both had just submitted their 1949 estimates to their respective regional offices, and they wondered if Reclamation was to cover Park Service estimates. Regional Director Tomlinson reassured Greider that he believed this new policy did not apply to recreational areas already taken over by the Park Service, so the budgets remained unaltered. [36]

Termination and Relocation

While Reclamation and the Park Service worried about budgets for the newly formed Coulee Dam Recreational Area, Indian tribes had much larger issues confronting them. Faced with their very survival as federally recognized tribes, the Colville and Spokane tribal governments did not have much time during the 1950s and 1960s for issues at the adjoining recreation area. Federal Indian policy changed following World War II and bureaucrats were joined by many Indians, particularly returning war veterans, in favoring full integration of native people into mainstream American society. This led to federal policies of termination (ending federal trust status) and relocation throughout the United States, as well as the work of the Indian Claims Commission.

The push for termination began during President Harry Truman's term and accelerated following the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952. It started with the Zimmerman Plan in 1947 that ranked tribes according to their perceived ability to survive withdrawal of federal trust status. Truman's 1950 appointment of Dillon S. Myer to be Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs ( BIA, formerly Office of Indian Affairs) put pressure on both the tribes and the agency. Myer proposed training and job placement assistance for those who wanted to leave the reservation, and he offered help in developing industrial programs for those who chose to remain. Both programs shared the same goal, that of making Indians independent of the federal government. Although Myer urged BIA officials to help tribes understand the effects of termination, he insisted on proceeding even without tribal cooperation. Myer also reorganized the BIA, and there was talk of eventually terminating the agency along with the tribes. In 1953, the Republican Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108 with little discussion. Supported by the Department of the Interior, the bill established the policy of termination, ending the tribes' status as wards of the government and moving to withdraw all federal responsibilities to Indian tribes. Bills targeting specific tribes followed. [37]

Under termination, tribes were given two options to dispose of their tribally owned lands: either they could form a corporation to manage the properties under a trustee of their choice, or they could liquidate their assets and distribute the proceeds among tribal members. Should a tribe choose neither option, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to transfer titles to a trustee who would then liquidate the holdings. Once targeted for termination, tribes had two to five years to complete the process. The push to terminate tribes weakened by the late 1950s, especially as states and local governments began to realize that the costs of taking over social services on former reservation lands far exceeded any benefits from taxing these lands. Before the effort ended, only 3 percent of all federally-recognized Indians were terminated. [38]

|

[The word "termination" spread] like a prairie

fire of a pestilence through Indian country. It stirred conflicting

reactions among my people; to some it meant the severing of ties already

loose and ineffective; others welcomed it as a promise of early sharing

in tribal patrimony. Many outsiders realized that it provided a first

step towards acquiring Indian resources. The great majority of my

people, however, feared the consequences. The action of Congress,

accompanied by the phrase "as rapidly as possible," sounded to them like

the stroke of doom.

-- George Pierre, former CCT leader[39] |

As a corollary to termination, the federal government pushed a policy of relocation to encourage Indians to move from reservations to urban areas where there were more job opportunities and the potential for a higher standard of living. The BIA believed that once tribal members adjusted to their new lives in the cities, there would be no need for reservations. Some Indians volunteered to move and in the decade following World War II, approximately 100,000 left reservations throughout the country. The change proved disastrous for many, however, who suffered profound culture shock and lacked basic urban skills such as knowing how to use a telephone. By the late 1950s, the BIA changed the focus from relocation to employment assistance, attracting interest from Indians wanting vocational training. Indian centers opened in cities to help relocated Indians. Ultimately, the failure of both termination and relocation helped fuel the Red Power movement of the 1960s. [40]

In 1954, a congressional report rated both the Spokane and the Colville Indians as able to handle their own affairs and thus ready for termination. The STI, however, moved quickly to squelch this idea. In a strong statement made to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1955, the tribe said that it was neglected by the federal government. When the Agency had moved from the Spokane to the Colville Reservation nearly thirty years earlier, the tribe had lost many services to which they were entitled. During these years, the STI had only a sub-agency and consequently the tribe had received essentially only what was left after the Colville Agency took first choice. The STI blamed the BIA for this and went on to suggest that the federal government improve services to tribal members instead of withdrawing support. The STI refused to consider termination until their long-standing land claim was settled by the Indian Claims Commission. The tribe later asked to be separated administratively from the CCT in 1966, due to "widely divergent" ideologies. [41]

The CCT was not able to escape the termination effort without a difficult fight that caused great dissension within the tribes. The BIA informed the Colville Business Council in February 1953 that it would assign technical staff to help them work on termination, which the Council had already been studying. The process began in earnest, however, with the passage of Public Law 772 on July 24, 1956. This law returned to tribal ownership over 800,000 acres of former tribal lands that had not been disposed of under the Homestead Act. A condition of this land return was that the Colville Business Council had to propose legislation to terminate federal supervision within five years. Ironically, had the CCT voted in favor of the Indian Reorganization Act twenty years earlier, the Secretary of the Interior could have returned these lands to the tribe without any termination provision, but he was not allowed to do this for a non-IRA tribe. A group within the CCT that favored termination drafted legislation that was introduced in Congress in 1962, but the bill died in committee. Similar legislation was introduced but not passed in each Congress through 1970. The Park Service fully expected termination to pass and planned to assume responsibility for fire protection for lands on the west side of the lake. The movement for Colville termination came as the country was shifting away from this program and tribes across the nation fought against these CCT bills. On the Colville Reservation, however, there were many who supported the move, and some of these supporters were elected to the Colville Business Council. Although termination plans were eventually dropped, hard feelings persisted among pro- and anti-termination factions on the reservation. [42]

Indian Claims Commission

The work of the Indian Claims Commission (ICC) provided a partial counterbalance to the post-war federal programs of termination and relocation. The 1946 legislation that established the ICC set a five-year period during which tribes could file claims, followed by another five years during which the three-person commission would reach decisions. The Commission heard 852 cases in the first 5 years. To accommodate the large number of claims, Congress allowed extensions until it finally dissolved the ICC in 1978. The STI, through the law firm of Wilkinson, Boyden & Cragun (later Wilkinson, Cragun & Barker), filed a claim in August 1951, asking for additional compensation for lands taken in 1887. The tribe asserted that the amount paid, totaling thirty-two cents per acre for 3.14 million acres, was too low and the ICC agreed, awarding the tribe an additional $6.7 million in 1967. In addition, the Spokane Tribal Council asked the Secretary of the Interior in 1949 for compensation for the flooding of nearly 3,000 acres of land following completion of Grand Coulee Dam. They waited too long to file this claim with the ICC, however. At the time of the large CCT settlement in the 1990s, the STI asked the House of Representatives to waive the statute of limitations and allow similar compensation to the tribe for its fishery loss and share of power revenue, noting that to compensate the CCT but not the STI "would be an egregious miscarriage of justice." This case is still pending. [43]

The CCT also filed a number of claims with the ICC. Various tribes of the CCT claimed millions of acres had been taken unfairly. After the Secretary of the Interior initially opposed these claims, the CCT finally agreed in 1956 to a settlement of $1 million for a total of 1.7 million acres. Tribal members received a payment of $350 per capita in 1961. The tribes filed another claim in 1973 that dealt primarily with the loss of their fishery due to Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams; this claim was settled for $3.257 million in 1978. An even more important case concerned the CCT claim to power revenue from Grand Coulee based on their claim to Columbia River waters. The tribes began negotiating with the government in the mid-1970s, but a special task force found the tribal legal claims without merit in 1980. The tribes sued and eventually won a settlement in 1994 in the Court of Appeals that included a lump sum of $53 million and annual payments of at least $15.25 million. [44]

Testing the Waters: Indian Rights,

1949-1960

As the federal government was looking into ways to end its trust responsibility to the tribes, the Spokane Tribe quietly began to test the limits of Indian rights at Lake Roosevelt. The first target was lands on the Fort Spokane Military Reservation, administered by the OIA (and later by the BIA). Department of the Interior (DOI) Solicitor Nathan R. Margold had ruled in December 1939 that the government did not need to compensate any tribe for lands flooded at Fort Spokane, reasoning that there was never any treaty concerning these lands. Furthermore, he wrote, when the President set aside lands for a potential reservation in November 1873, the government assumed that the tribe's acceptance of the reservation meant that they had relinquished title to any lands outside of its boundaries. Local Reclamation and Park Service staff eyed the remaining Fort Spokane lands above the 1,310 line as early as 1943 because of the location's recreation potential, but departmental officials cautioned against trying to withdraw the remainder of the military reservation, noting that the land was not required for the purposes of the Columbia Basin Project. Superintendent Greider raised the subject again in 1947 and noted that he had the support of Wade Head, Superintendent of the Colville and Spokane reservations. While the Commissioner of Reclamation still opposed the idea, Reclamation's Regional Director enthusiastically supported withdrawal of these lands for recreational development as part of the new national recreation area (NRA). [45]

While Reclamation and the Park Service discussed the propriety of adding Fort Spokane lands to LARO, the Spokane Business Council passed a resolution on March 17, 1949, asking for confirmation of their title to these same lands. This claim distressed Park Service officials who believed that the STI was trying to get Margold's 1939 decision reversed. "It is unfortunate that this somewhat belated assertion of rights in the land by the Indians will delay, if not entirely block, the addition of the lands to the recreational area," wrote Paul R. Franke, Acting Director of the National Park Service, in October 1950. He realized, however, that the agency could do nothing until the BIA had completed its study and the Department of the Interior made a decision. [46] Due to the uncertain situation, the Park Service decided to forego any plans for the main fort grounds and instead planned to confine its concession developments there to the lower bench area that it already controlled. BIA Commissioner Myer sided with the STI early in 1951, noting that the 1873 agreement to relinquish lands, including the fort grounds, had never been ratified and there had been no compensation for the loss of this land. He said that the Indians believed that they had never given up their claims to these lands and thus still had "valid rights in and to the lands based on their aboriginal use and occupancy thereof." The BIA agreed that the Indians at least had a "strong moral claim to the land." [47] The Solicitor concurred with this moral claim and went further to say that even though aboriginal title had been extinguished, the STI might be entitled to compensation. He also suggested that the lands could not be withdrawn for recreation purposes unless Congress authorized such action. [48]

Faced with these opinions and tribal opposition, the Park Service attempted to reach a compromise on Fort Spokane lands. The agency realized that it might not need all of the 331.31 acres and decided to propose a division of the lands designed to achieve legislative approval. They hoped to secure a water supply for recreation development and in return were willing to offer the Indians a concession there for the sale of arts and crafts. BIA representatives supported this proposal as long as the United States agreed to recognize tribal ownership of the fort lands outside the recreation area. They believed that the Indians might support the settlement once they recognized the advantages of federal money used for recreation development, along with a display for local handicrafts. The STI refused to capitulate, however. At a meeting in April 1952, Council members reiterated that they still were not sure of their rights to the Fort Spokane lands and until this was cleared up, "they could do no horse trading without horses to trade." [49]

Despite this setback, Park Service officials continued unilaterally to make plans for the development of the Fort Spokane lands during the next few years; these plans covered not only the strip of land owned by the Park Service, but also the entire fort grounds administered by the BIA. Their concern increased in 1957 when they discovered that the BIA recently had abandoned the old fort buildings. LARO Superintendent Hugh Peyton pointed out the historical significance of the area and warned that removal of any part would be tragic. He asked the BIA to hold off any disposal until the Park Service could assess the site and its preservation possibilities. Because the public was increasingly interested in historic sites, Peyton believed that tourists to the fort would benefit the reservation's economy. [50]

While the STI was hoping to negotiate an agreement with the Park Service over Fort Spokane lands, some tribal members continued to push for an expansion of their rights on the reservoir. William Kieffer, a Spokane Indian who operated a small gas station on Highway 25, wanted to install a dock with gas pump on the Spokane Arm in 1958. LARO officials discouraged this and viewed the action as an indication that the STI was questioning the Park Service's authority to regulate and administer concessions within the Indian Zones. BIA representatives warned the Park Service that the Spokane Tribal Council was "considerably agitated" by the ruling against Kieffer. They had changed their thinking on Fort Spokane and now wanted to trade these lands for shore lands bordering the Spokane Reservation. LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson referred Kieffer's request to the Field Solicitor who ruled in favor of the Park Service, saying that the 1946 agreement gave the agency sole responsibility for approving and supervising concessions catering to the general public on any site in the recreation area. [51]

Attorneys for the STI issued a lengthy opinion strongly disagreeing with the Solicitor's conclusions. They argued that before construction of the dam, Indians had exclusive rights to license non-Indians for hunting and fishing on reservation lands, and the 1940 Act did not terminate these rights. They also had the right to exclude non-Indians from such activities, and "if the Indians could exclude, they could license." They concluded that Congress did not intend to limit Indian rights further with the 1940 Act since this

would not be fair in light of the rights previously enjoyed by the Indians. . . . Thus, we say the public should be excluded from the land portions of the Indian Zone, and that the Indians can use the land portions to set up concessions or make such other ordinary uses as they previously could. If they cannot do at least this, then they are entitled to compensation for loss of valuable rights . . . .

Actually, the Indians do not want further compensation; they want to share to some small extent in the economic opportunities made available by the vast lake created by Coulee Dam. The river bank land and access to the water was formerly one of their most important assets; it would be a most serious loss for them — not only of revenue but of opportunities for employment and self-enterprise — if they were to lose all benefits in this asset. The Act clearly contemplates that this asset was to be an "Indian Zone," and that the Indians were to have special rights in it. The Field Solicitor's opinion would deprive them of those special rights. [52]

The attorneys concluded that the Park Service could neither prohibit nor regulate concessions in the Indian Zones. Although such control would be advantageous, the agency must not trample Indian rights to gain it. The Indians were willing to cooperate and negotiate agreements with the Park Service, but until then, "they resist any attempted abridgments of their rights." Soon after this, tribal representatives met with Department of Interior (DOI) officials, and all agreed to have the Solicitor consider the issues. [53]

Superintendent Homer Robinson downplayed this disagreement, saying that he did not know of any actual plans that Indians had for concessions on the lake. Instead, he believed that they only wanted to establish a policy allowing them to provide services to the general public. Nonetheless, he worried that the Park Service might have to give Indians "preferential contracts to protect them from marginal operations intended only to skim the cream from the available business." [54]

The STI's request for a Solicitor's determination of their rights languished for nearly a year, during which time the Park Service was moving closer to acquiring the Fort Spokane lands from the BIA. A tribal attorney complained about this, saying that the Indians wanted to be part of any recreation plans for the area near their reservation and they hoped to work out an agreement with the Park Service. They were unable to proceed with this, however, without a determination of their rights. Because the STI was so poorly compensated for the loss of their lands, the attorney believed it was only fair for the Park Service to share the economic potential of the new recreation area. When the Solicitor's opinion finally arrived in May 1960, however, once again it went against the tribe. Deputy Solicitor Edmund T. Fritz concurred with the Field Solicitor's 1958 opinion that Indians, "like anyone else," needed to get a Park Service permit before developing or operating public concessions in the Indian Zones. [55]

In the spring of 1960, the Park Service not only prevailed with the Solicitor's office but also acquired the entire 331.31 acres of Fort Spokane. Public Land Order No. 2087 of May 9,1960, revoked the 1882 Executive Order that had established the military reservation, along with the Executive Order of November 17, 1887, that modified the boundaries, and turned the lands over to the jurisdiction of the Park Service "for use as an administrative, museum and historic site in connection with the Coulee Dam National Recreation Area." [56]

Turning Up the Heat: Indian Rights,

1960s

The CCT briefly raised the issue of fishing rights in 1963 when a tribal game officer stopped a non-tribal member who was fishing within the Indian Zones without a reservation permit. The officer did not prohibit the man, who had a state fishing license, from fishing, but he told him to purchase a tribal permit and forward the information to the tribe or risk having his case turned over to the U.S. Attorney. When Superintendent Robinson heard about the incident, he asked the Field Solicitor if the tribes had the right to require special permits within the Indian Zones so the Park Service could inform visitors to prevent such misunderstandings. The Solicitor replied that although the BIA required a special permit to fish on any waters within the reservation, he did not believe that it had yet been decided if this applied to the waters of Lake Roosevelt. He thought that this was probably an isolated incident brought on by a tribal game officer who was unclear about his authority. He offered to write an opinion if there were a repeat incident, but the issue remained dormant for several years. [57]

Despite its loss over Fort Spokane lands, the STI continued to push for both definition and expansion of Indian rights at Lake Roosevelt. The tribe hired a consulting firm in 1967 to complete a land-use study of reservation lands, including shore lands. According to the tribal attorney, the consultants needed to know what rights tribal members had to shore lands and if there were additional rights that they could negotiate with the Park Service. Tribal attorney Robert D. Dellwo met with LARO Superintendent David Richie in August 1968 to discuss mutual rights and responsibilities in the freeboard lands within the Indian Zones. During the evidently cordial meeting, they worked out an agreement under which Park Service rangers would issue permits on the spot to tribal members camping on freeboard lands, allowing them to have campfires except when fire danger was high. Dellwo explained that the tribe did not intend to provoke a controversy over Indian rights at this time and instead assumed that the Park Service would recognize these rights and cooperate with the tribe as it went ahead with its plans. The tribe understood "that the best safeguard of its rights is in cooperation and in the ultimate exercise of the tribe's responsibilities in regard to them." [58] Richie responded that he believed that the interests of the Park Service and the tribe were "in essential harmony" and that they would be able to reach mutual understandings. [59]

The issues became more difficult, however, as the STI moved from campfire permits to water rights in 1969. Dellwo complained to Richie that the Park Service had charged tribal member William Wynecoop $25 for a water pump permit to withdraw water from the lake. He believed that tribal members retained the right of free access across freeboard lands to use the water and thus should not be charged. In addition, he warned that such actions were "a real irritant" to both the tribe and the Business Council and should be left dormant until a decision was reached on water rights. [60] Superintendent Wayne Howe compounded the problem two years later when he informed Wynecoop that he needed a pump permit from the Army Corps of Engineers in addition to his Park Service permit. Dellwo complained again that it had been difficult enough for the STI to develop a consensus of operation with both the Park Service and Reclamation, and he believed that it should not be forced to work with the Corps as well. He asked the Corps to reconsider this requirement to avoid a legal confrontation over Spokane tribal water rights at Lake Roosevelt. The STI was concerned that if the Corps had the right to grant permits, it also had authority to refuse them, causing a clash with tribal property rights. Dellwo suggested that the Corps delegate its regulatory authority at Lake Roosevelt to the Park Service. The Corps at first reiterated its authority in this situation but subsequently deferred such permits to the Park Service. [61]

While the debate over permitting Wynecoop's pump was irritating to the STI, the more serious water rights debate centered on a proposed withdrawal for a uranium mill on the reservation. Western Nuclear, Inc., conducted a feasibility study for a processing plant in 1969, which included a daily requirement of 17,500 tons of water or 45,000 acre feet/year, with most coming from Lake Roosevelt. The STI, which was leasing land to the company, argued that there should be no charge for this water since the tribe believed it retained water rights to the Columbia River. Dellwo said that the "unconscionably low" financial compensation paid to the STI in 1940 for lands taken for reservoir construction indicated that the government intended the tribe to be compensated instead with liberal rights, including the same water rights as before the Act of June 29, 1940. [62]

In making his case, Dellwo cited the Winters Doctrine, a precedent quoted in most Indian water rights cases. The doctrine stemmed from a 1906 decision, upheld by the Supreme Court two years later, in a case brought by the government against a group of Montana farmers who had appropriated so much water from the Milk River that there was not enough left for Indian use downstream on the Fort Belknap Reservation. The court ruled that establishment of a reservation implied that sufficient unappropriated water was reserved for the tribe to accomplish the purposes for which the reservation was established. These rights began the day the reservation was established and continued in perpetuity. The Indians could use the water in any way that fulfilled the purposes of the reservation, and they could not lose these rights if they did not use the water. Thus, tribal water rights usually superceded those of farmers since the reservations were established before most western waters were appropriated. Despite this powerful precedent, the federal government generally did not assert tribal rights under the Winters Doctrine for over fifty years. The 1963 Arizona v. California case reaffirmed the doctrine, and both the STI and CCT soon recognized its applicability to Lake Roosevelt. [63]

The STI's request drew a mixed response from Reclamation officials. One of them took exception to the tribe's claim that it had not been fairly compensated for lands lost to the reservoir and suggested that it could take its case to the Indian Claims Commission. He noted that these waters, raised "at great expense," were now available for irrigation and were "no longer in or being maintained in their former less advantageous natural state." [64] Grand Coulee Project Manager W. E. Rawlings pointed out that water users were not charged for water withdrawal, and he asked for advice on whether or not to continue this policy. Reclamation Regional Director Harold T. Nelson reassured him that there was plenty of water to meet project needs, and he saw no conflict between Reclamation interests and the proposed mining development. More important to him was the need to avoid application of the Winters Doctrine, which was being invoked at other federal reclamation reservoirs. "We see no need to involve this large-scale battle of 'principles' in this situation," he wrote, since there was plenty of water for both Indian and non-Indian uses. [65]

After Reclamation officials appeared to approve a free water withdrawal for Western Nuclear, the STI upped the ante. In its proposed lease to the mining firm, the tribe included a statement that "the tribe will make no charge for these waters and asks that lessee not make any payment for them to any department or agency of the United States Government or to any one else." This concerned Field Solicitor Paul Lemargie, who believed it might create a precedent that was inconsistent with the views of the Solicitor. [66] Assistant Solicitor J. Lane Morthland met with tribal attorney Dellwo in February 1971, and assured him that there would be no charge for water used by Western Nuclear as long as either the company or the tribe obtained a valid state water right along with a special use permit from the Park Service. But Dellwo informed him that the "Indians do not want to recognize the need for securing a state water right in their own name." Morthland then suggested the alternative - and circuitous - solution of having the tribe work out an agreement with Reclamation for water to irrigate a selected tract of land; once approved, the water could be used by either the tribe or a lessee for uses other than agriculture, at no charge. This "would in effect be a recognition by the Department of a Winters Doctrine right without adjudication," noted Morthland. Dellwo agreed, "provided it would not jeopardize or prejudice the Indians' claim to additional waters under a Winters Doctrine adjudication." [67] Later, however, a Reclamation official granted the STI the right to divert 646 acre feet of water annually, but added that Western Nuclear still would need to get permits from the Park Service and the Corps and pay required fees. It is not known how the STI reacted to this requirement. [68]

Bringing Things to a Boil: Indian Rights,

1970s

While the STI was pursuing its claims with the assistance of tribal attorneys, unrest was starting to sweep through reservations across the country. In Washington, state officials did not recognize many Indian treaty rights and attempted to tightly control Indian fishing. Indians began to protest in the 1950s, staging "fish-ins" on the lower Columbia as a form of civil disobedience. Arrests led to test cases in court and finally to what became known as the Boldt Decision in 1973, in which the federal government represented fourteen tribes in a suit against Washington state, defended by Attorney General Slade Gorton. Judge George H. Boldt ruled in favor of the tribes, saying that they were entitled to half of the catch that migrated through their usual and accustomed fishing sites. This meant that the government had to limit ocean fishing to prevent decimation of river runs. In addition, Boldt affirmed tribal rights to regulate and manage their share of the fishery. [69]

Nationally, the civil rights movement began to resonate with American Indians, especially the younger generation. Discontent increased as spending cuts diminished popular anti-poverty programs that had benefited many young Indians. The American Indian Movement (AIM) formed in Minneapolis in 1968 and urban Indians soon began to rally to the cry of "Red Power!" Three major incidents galvanized Indians across the country and drew worldwide attention to Indian demands. These included the takeover of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay in November 1969; the Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan to Washington, D.C., in 1972 and the subsequent takeover of the Department of the Interior building; and the bloody occupation of Wounded Knee that began in February 1973, lasted seventy-two days, and resulted in the deaths of two Indian men and the paralysis of a federal agent. [70]

During this time, the push for Indian rights at Lake Roosevelt took on an active dimension to counterbalance the previous legal approach. The CCT joined the fray in August 1971 when the tribal council banned all hunting on reservation lands, complaining of trespassing by non-tribal members along with a basic lack of respect shown to tribal members and their lands by these uninvited visitors. CCT Game Officer, Howard "Doodle" Stewart did not favor such a closure but noted, "We are sitting on a powder keg." [71] The hunting ban expanded in November to include the requirement for a tribal fishing license, first for waters within reservation lands and later for Lake Roosevelt. Stewart followed guidelines from the tribal Fish and Wildlife Committee but kept local Park Service officials informed of the changes. LARO Superintendent Wayne R. Howe appreciated the information since he wanted to keep the public informed of the new requirements to avoid inadvertent violations, but he knew that the issue would have to be resolved in court eventually. The Washington Department of Game reacted more vigorously and claimed that the state owned the waters of Lake Roosevelt and thus there was no special license required. The CCT disagreed, however, and believed that all of the waters adjoining the reservation belonged to the tribes. "Let someone else prove they're not [ours]," challenged CCT Chairman Mel Tonasket. He noted that although they would have to fight for their rights, "we're not going to back up any more. We're not going to stop making waves." [72] BIA Superintendent Sherwin Broadhead supported the CCT claim while other officials went so far as to imply that the agency believed that the purchase of Indian lands for the Grand Coulee Dam had been "accomplished illegally." [73] During this time of confusion, Howe appealed for help. "I hope that some statement can be forthcoming from the Director's office or Secretary's office before too long," he wrote, "as this whole thing can get a bit sticky by next summer." [74]

The situation had already become sticky, however, as trouble erupted at Sanpoil campground during the summer of 1971. Apparently a contingent of Indians from outside the area spent time there and hosted loud parties that lasted so late that others no longer enjoyed camping at Sanpoil. Campers had to be evacuated after one incident, which may have involved threats with guns. Prominent CCT members, backed by BIA officials, aired their concerns at a November meeting with Park Service officials. At that time, the CCT expressed interest in taking over operations at Sanpoil campground. Howe agreed that this was possible under the Tri-Party Agreement, and he said he would send any formal request through channels to see if it could be accomplished. [75]

In an effort to stave off further trouble, LARO staff met with members of the Colville Business Council, a CCT Game Officer, and BIA officials in April 1972. Superintendent Howe acknowledged that he wanted to avoid any trouble like the recent Sanpoil campground incidents and he asked for cooperation from the CCT to avoid responding with Park Service law enforcement. CCT members suggested several solutions: turn the campground over to the tribes to run, provide full-time staffing to keep tourists from trespassing on Indian lands, or shut it down. Underlying these suggestions were long-standing grievances, including a belief that the lands had been taken illegally and resentment over exclusion of the tribes from the Tri-Party Agreement. BIA officials supported the CCT claims and fanned the embers of resentment. George Davis, Programs Officer with the BIA, suggested that Sanpoil campground should be closed to see if "we can get the issue hot enough to get it settled." LARO Chief Ranger Paul Larson countered that such an action would generate negative publicity and might "build up so much . . . resentment that you would never be able to take it over." Despite the tensions, the meeting ended on a positive note with discussions about establishing a program of cultural demonstrations. [76]

With the campground controversy still unresolved, the CCT renewed its push for control of fishing by passing an ordinance to require all non-Indians to purchase a tribal license before fishing in waters claimed by the tribes. These included all of the Okanogan River and half of each reservoir, including Lake Roosevelt, bordering the Colville Reservation. Despite the Regional Solicitor's opinion that there was no basis for this action, the CCT threatened to arrest anyone caught fishing without a tribal permit. Local LARO staff felt caught "on the horns of a dilemma: Responsible for keeping the public informed, but unable to sanction, or dispute the issue." [77]

The public did not take kindly to CCT demands. In March 1972, Superintendent Howe warned of the possibility of violence against any tribal game warden who arrested a non-Indian. Some non-Indians felt strongly about what they saw as high-handed actions by the CCT, causing Howe concern that Lake Roosevelt had "the potential of becoming a battleground with the Service in the middle." After CCT's Law and Order Committee asked if the Park Service would allow CCT officers to sell and enforce tribal licenses within the Sanpoil campground, Howe again appealed to the regional office for guidance on ramifications of enforcing tribal law in the Indian Zones and emphasized that he needed answers as soon as possible. [78]

Problems at Sanpoil were not easily resolved, however. Incoming Superintendent William N. Burgen described the campground as a "festering thorn in the side" of both the Park Service and the CCT and he noted that "only close coordination with the Council and mutual respect have prevented an unpleasant showdown at the site." In 1972, the site required three people per day to prevent weekend disturbances, more staffing than any other LARO area. [79] As rumors of tribal takeovers spread to neighboring towns, the Wilbur Chamber of Commerce came out in opposition to control by any ethnic group. The dam, lake, and recreation facilities had been built with taxpayers' money "and the combined efforts of all citizens regardless of race, color, or creed," the Chamber wrote. "By the same token, these facilities should be for the equal and non-discriminatory use of all citizens." [80]

1972 Task Force

Increasing tension at Lake Roosevelt led Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton to appoint a Task Force to hear tribal complaints and attempt to find solutions for the conflicts plaguing the recreation area and adjoining reservations. Chaired by Emmet E. Willard, Morton's Field Representative in Portland, the Task Force included members of the Colville Business Council and Spokane Tribal Council; tribal attorneys; various specialists from both the Colville and Spokane agencies; local and regional representatives of the Park Service, Reclamation, and BIA; representatives of the Corps of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration (BPA); specialists with the Department of the Interior; and various Washington state officials.

| Task Force members heard about the reality of reservation life from a passionate and angry Mel Tonasket. He described the terrible poverty and 40 percent unemployment rate on the Colville Reservation and wondered why just 5 Indians were employed at the dam with its workforce of nearly 290 people. "The more I talk the more angry I get, because I see my people hungry, I see my people living in shanty houses and I go off reservation and I see new . . . homes going up all over," he said. "I see a white man cry if he only makes $6,000 a year. I could cry everyday." [81] |

When the Task Force first convened on February 7, 1972, tribal representatives raised issues of concern, giving agency personnel a chance to hear their grievances. Mel Tonasket, CCT Chairman, touched on many hot-button issues: losses of land, buildings, cemeteries, and fish stemming from reservoir construction; lack of compensation for these losses; and the claim of rights under the Winters Doctrine for the use of Indian waters for power production. He also discussed the frustrating irony that Grand Coulee was built to facilitate irrigation and generate electricity, using Indian land and water, yet the reservations had no irrigation projects and paid high electrical rates. Others mentioned the irritations caused by both the Park Service and the Corps requiring permits for the same project, but LARO Superintendent Howe noted that neither he nor STI attorney Dellwo had been able to change this. Dellwo said that he would like to see the Task Force reevaluate the Tri-Party Agreement and clarify the issue of paramount rights. [82]

When the discussion turned to Indian employment, Howe noted that he had hired two Indians for his permanent staff using excepted appointments, as the BIA had also done. He admitted that this might not be legal but said that Civil Service in Seattle knew of his actions. Willard assured him that DOI officials believed such use of excepted appointments was legal, and Sherwin Broadhead, Superintendent of the Colville Agency, expressed his appreciation for Howe's initiative. [83]

After this first meeting, Willard evidently asked members to submit written questions to help guide the direction of the Task Force. Some dealt with topics brought up in the first session, such as land acquisition and the need to revise the Tri-Party Agreement, while others headed into new areas. Park Service Regional Director John A. Rutter was concerned about jurisdictional issues. What were the implications of the CCT move to require tribal fishing licenses? What were the geographical limits of this tribal authority? What court system would try these cases? Would the tribes honor the established responsibilities of the Park Service and Reclamation within LARO boundaries? Would they allow the Park Service to help with recreation planning on reservation lands that adjoin LARO? Did the tribes honor the original acquisition of Indian lands by the federal government? [84]