|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 5:

Charting the Course: Managers and Management Issues

Park managers and employees have guided the development and operations of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO) from its inception. The initial skeleton staff had the monumental task of establishing a recreation area where there had been neither a park nor even a lake before. Over the years the staff has multiplied and the jobs have specialized. Working first under the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement and now under the 1990 Cooperative Management Agreement, eleven superintendents and their staffs have built and maintained facilities, developed and run a wide variety of programs for the public, and enforced an increasingly complex set of regulations, laws, and agreements. This chapter profiles park managers and discusses selected management issues, some resolved and others ongoing, that have helped shape LARO and its daily operations over the years.

Superintendent Highlights

The National Park Service began working at Lake Roosevelt in 1941, five years before it accepted management responsibilities for the area. After nearly thirty years under Park Service direction, LARO officially became a unit of the National Park System following passage of the Act of August 18, 1970 (Public Law 91-383).

During the sixty years of Park Service management at LARO, there have been eleven superintendents. Three of them (Claude E. Greider, Homer W. Robinson, and Gary J. Kuiper) had relatively long tenures, ranging from nine to twelve years; two (Howard H. Chapman and David A. Richie) remained for brief terms of less than two years; and the remaining six (Hugh Peyton, Wayne R. Howe, William N. Burgen, William W. Dunmire, Gerald W. Tays, and Vaughn L. Baker) have led the park for periods of three to five years.

Claude E. Greider, the first superintendent at LARO, guided the park through the entire planning stage and into the initial development. Greider was a State Supervisor with the Park Service in Portland when he was appointed in November 1939 to head the Problem No. 26 committee that was looking into the recreational potential for the lake that would form behind Grand Coulee Dam. He secured the services of Philip W. Kearney, Associate Landscape Architect, who became the first Park Service employee at the slowly rising reservoir in March 1941. Greider joined him in late December 1942, doubling the staff. With the arrival of Frances Fleischauer, a clerk-typist, in March 1943, the initial Park Service office was complete. Budgets were equally small, with just $10,000 a year supplied from Reclamation. Because it came from project funds, the appropriation could be used only for administration and planning, with nothing for construction or development work. [1]

Both personnel and budgets increased by the late 1940s. Greider's staff grew following the signing of the Tri-Party Agreement in December 1946 that established the Park Service as the agency in charge of administering the national recreation area (NRA). LARO gained an engineer, landscape architect, chief ranger, and clerk-stenographer by May 1947, but Greider still termed this number "barely adequate" to do the current work. [2] By mid-1950, another ranger and a boat operator had joined the staff, bringing the total to eight. The initial Congressional appropriation of $26,000 for LARO came in FY1949. Greider knew he needed much more money to start development work at the park. He was particularly concerned that the Park Service get basic road and utility work completed to encourage private development with concessionaires. In addition, he recognized the need to do a massive debris cleanup on the lake to clear the waters for boating. Greider told the Regional Director that he had no suggestions for the Physical Improvements budget "other than to triple the amount of funds" if possible. [3] The following year did indeed bring a sizeable increase, with $48,600 for Administration, Protection, and Maintenance, and $137,200 for development, including roads, employee housing, and reservoir cleanup. [4]

During his eleven-year stay at the NRA, Greider worked "by the book" in planning, development, and regulations. When wartime rationing was lifted, local residents were ready to take advantage of camping and boating opportunities on the new lake. Lack of appropriations had prohibited any Park Service developments, however, and Greider discouraged recreational use of the area until the federal agency could proceed with "a conservative and orderly program." [5] This eventually caused resentment toward the Park Service, which was compounded during the prolonged fight over regulations for the new NRA. Much of this may have been due to Greider's personality, which one long-time employee described as "kind of . . . pompous." [6] He was less of a field person than later superintendents, but his office and organizational skills may have been what were needed to get the park started. Greider transferred to the Portland Office on August 12, 1953, where he took charge of the Rogue River Recreation Survey. [7]

Hugh Peyton arrived August 16 to replace Greider. He had experience at one of the two other recreation areas at the time, having been Custodian and Superintendent at Millerton Lake in Friant, California. Peyton was familiar with some of the issues facing LARO, particularly the controversy over regulations, since he and Greider had worked together to revise the rules in 1951. In contrast to the "spit-and-polish" style of the first superintendent, Peyton was a down-to-earth leader who let the employees know he was on their side. "He just turned us loose," remembered Don Everts. "Do it right or else you'll get your butt chewed." [8] Peyton was "a junk gatherer" like Everts, and the two of them procured many vehicles and loads of materials from their regular scanning of General Services Administration catalogs. These surplus materials were used throughout the park, from liners in pit toilets to the radio system. Park construction really began under Peyton, and he won the approval of many local people who were pleased to see any development at LARO. One man reported that the superintendent and his crew were "doing miracles with small money," well beyond anything Greider had done. Park supporters were pitching in to help with privately owned bulldozers and donated labor to provide "Free access to Roosevelt Lake for every body." [9] Peyton retired in January 1958. [10]

|

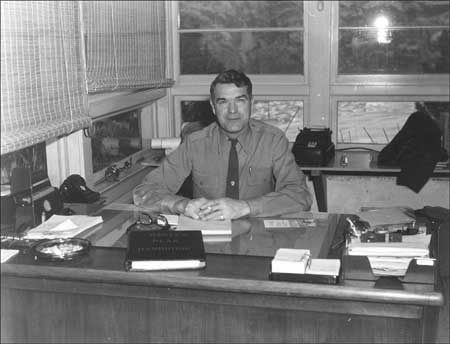

| Superintendent Homer Robinson, January 1960. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Homer W. Robinson replaced Peyton as Superintendent, arriving at LARO February 10, 1958. Robinson began his federal career working on fire lookouts for the U.S. Forest Service in Oregon. He then transferred to the Park Service and was assigned to Yosemite, where he worked as Assistant Chief Ranger. He then served as Superintendent at Millerton Lake Recreation Area in California, followed by national monuments in Colorado. During his tenure at LARO, he guided the park during the major development work of the Mission 66 period. Robinson is remembered as a "hands-on" superintendent who liked to get out of the office and into the field where the action was. He particularly enjoyed running heavy equipment and periodically would "relieve" a LARO employee using a bulldozer during road or campground construction. His involvement continued with other types of work as well. For instance, during the restoration at Fort Spokane, Robinson fabricated the posts for the guardhouse veranda. Under Robinson's administration, LARO undertook major restorations of the historic buildings at Fort Spokane, acquired for the NRA in 1960. The park also developed its first interpretive program at the fort during this time. [11]

Even with the increased funding of the Mission 66 program, LARO still felt the pinch of too little money. As Sis Robinson, Homer's widow, remembered, "you were just working on a shoestring all the time." The Robinsons and other staff donated time to the park, helping with tree planting at the North Marina or clearing rocks and brush at Keller Ferry on a Sunday. Like Peyton before him, Robinson stretched the park budget by taking advantage of government surplus materials available through GSA catalogs. [12]

Although LARO was still a small, relatively isolated unit of the National Park System in the 1960s, Robinson and his wife believed it was important for the staff to understand their part in the larger system. Thus, whenever members of the regional office came to LARO, the Robinsons would gather their staff for a picnic with the visitors. "And we thought . . . that our people ought to know who all these supposedly important people were," Sis Robinson remembered. "We wanted our people to know . . . the people . . . who were making the rules and telling us what they wanted done. And I think we did that." A side benefit of these gatherings was giving the Regional staff a favorable impression of Coulee Dam and the NRA. After nine years at LARO, Superintendent Robinson retired from the Park Service in 1967. He and Sis lived in Myrtle Point, Oregon, for thirteen years and then returned to Coulee Dam in 1980. [13]

Howard H. Chapman served a brief stint as LARO Superintendent in 1967. After graduating with a degree in forestry from Colorado State University, he started as a ranger with the Park Service at Saratoga National Historic Park in New York. He later moved on to Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, the Northeast Regional Office in Philadelphia, Yellowstone National Park, and Albright Training Center in Arizona. He came to LARO in late February from Blue Ridge Parkway where he had been Chief Park Ranger. Chapman had considerable management training and evidently needed experience as a Superintendent before moving on to a higher position. In November 1967, he transferred to Grand Teton National Park where he served as Superintendent until December 1971. He then accepted an appointment as Regional Director for the Western Region, remaining in that position until May 1987. During his brief time at LARO, the park began to formalize policies for managing the NRA lands, including private docks. These issues got more attention during the next decade. [14]

Chapman was followed by David A. Richie, who came to LARO in November 1967 with a background in law. He graduated from Haverford College and followed it with a law degree from George Washington University in Washington, D.C. His initial years of government service included work as Assistant Superintendent at Mount Rainier National Park. He remained at LARO until August 1969, when he resigned to teach history at Westtown School, a private Quaker school in Pennsylvania. He then returned to the Park Service in July 1971 as the Superintendent for the George Washington Memorial Parkway. He followed this with an appointment as Deputy Regional Director of the North Atlantic Region from January 1974 to March 1976. Richie then transferred to the Appalachian National Scenic Trail where he served as Project Manager from March 1976 until July 1987. [15]

|

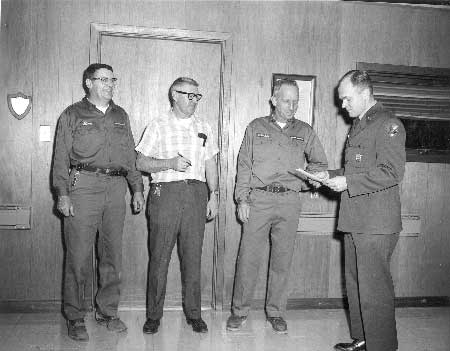

| Superintendent David A. Richie presenting awards to LARO employees Don Everts, Bert Norton, and Lee Randall, April 1969. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Wayne R. Howe replaced Richie at LARO in August 1969. He had been with the Park Service since 1946, working at Crater Lake, Olympic, and Sequoia-Kings Canyon. He was then promoted to Chief Ranger at Bryce Canyon, followed by Assistant Chief Ranger at Yosemite and Chief Ranger at Yellowstone. He had most recently headed the Branch of Visitor Activities Management at Park Service headquarters in Washington, D.C., since 1966. When he arrived at LARO, he was excited about what he perceived as the park's untapped recreational possibilities. Fishing enthusiasts had discovered walleye pike in Lake Roosevelt by the mid-1960s, and the popularity of this fish increased rapidly by the next decade, bringing recognition — and visitors — to LARO. [16]

One of the most challenging issues for Howe was the ramifications of the Red Power movement on the local reservations that took the form of disagreements over fishing rights as well as physical confrontations at the Sanpoil campground. He became the initial Park Service representative to the Secretary of the Interior's Task Force that formed in 1972 to investigate complaints from both the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) and the Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI). After he transferred to the regional office in July 1972, Howe represented that office on the Task Force. He continued to work as the Associate Regional Director for Management and Operations for the Pacific Northwest Region until February 1976. [17]

Following Howe's reassignment to the regional office, William N. Burgen took over as LARO Superintendent in July 1972. His previous station had been the Albright Training Academy at Grand Canyon, Arizona. His four-and-a-half year stay at LARO saw visitation rise once again, after falling during construction of the third powerhouse for Grand Coulee Dam. This increase in visitors was reflected in the budgets as well. The appropriation for FY1975 totaled just over $425,000. This increased dramatically the following year to $1,187,580, which included funding for FY1976 as well as the Transition Quarter as federal budgets made the change from calendar to fiscal year. Once back to the twelve-month appropriation in FY1977, the budget still showed a considerable increase over FY1975, with a total of $976,820. [18]

Under Burgen's leadership, the seasonal work force expanded to a total of seventy-two in 1976, with one in Administration, thirty-five in Maintenance, and thirty-six in the Ranger Division. These included six minority men and nineteen women (four of whom were minority). Burgen reported that the park had recruited a higher than average number of minorities for the Region but was lower than average with female recruits, "probably because we hire so few temporaries or seasonals in clerical positions." [19] The park also increased its participation in programs under Title I of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). Eight enrollees worked with Maintenance all summer, but the park had mixed reviews for the program. Even though the salaries were paid with CETA funding, the teenagers needed considerable supervision, and staff viewed the program "more as a service to the community than a benefit to the Area." [20]

During Burgen's tenure at LARO, tensions continued between the Park Service and the neighboring CCT and STI. Incidents on both reservations suggested to Burgen that the Indians were attempting to seize control of all the lands in the Indian Zones. The 1974 Solicitor's Opinion concerning tribal rights at Lake Roosevelt caused the Secretary of the Interior to order the Park Service, Reclamation, and Bureau of Indian Affairs to negotiate a new management agreement that would include the tribes. Negotiations stalled almost immediately, but the Park Service worked out an agreement with the tribes to return the federal campgrounds within the Indian Zones to tribal ownership.

Another trend that began under Burgen's leadership was the move to get control over special use permits and encroachments. The park hired its first Land Management Specialist in 1974, who began full-time work to inventory permits and check transgressions. This effort increased considerably a decade later.

Burgen transferred to Yosemite in January 1977 and was replaced by William W. Dunmire, who had been serving as chief of the Interpretation Division at the Washington Support Office. The budget increased regularly during Dunmire's tenure, rising from a total of $1,060,120 in FY1978 to $1,245,579 in FY1981. During the same time, the cost per visitor dropped from $1.40 to $1.34. By 1980, LARO had twenty-five permanent employees and seventy seasonals, in addition to twenty-four young people in the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) during the summer and another ten youths year-round in the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC). [21]

Dunmire led the team that wrote the first General Management Plan (GMP) for LARO in 1980. The Park Service moved away from Master Plans in the late 1970s because it found that it was often spending considerable money on elaborate plans that were never completed. The agency instead instituted biennial Statements for Management to supplement the more complete GMP, which ideally was updated every fifteen to twenty years. The GMP provides overall direction and management philosophy for individual units of the National Park System. During the GMP process, the Park Service consults with other agencies and members of the public to develop an approach to managing the park and its resources. Dunmire and LARO staff, assisted by the Denver Service Center (DSC), began work on the GMP in 1978. Information gained from a visitor-use survey that summer and four public meetings in 1979 provided direction for four proposed alternatives. The final document, approved in July 1980, described park facilities; provided visitor statistics and priority needs; and outlined directions for park programs. [22]

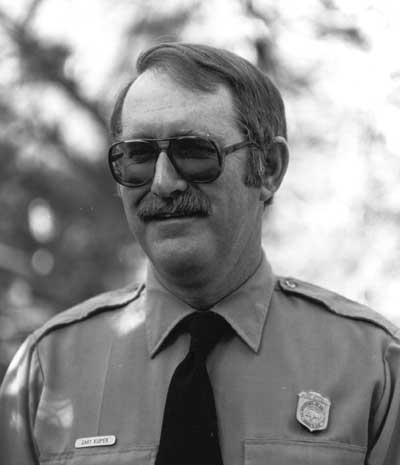

After Dunmire left LARO in February 1981 to take a position as Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns, he was replaced by Gary J. Kuiper, who arrived in May 1981 from the Grand Canyon. After his graduation from the University of Montana, Kuiper transferred from seasonal work with the Forest Service to full-time employment with the Park Service. His first job in 1961 was at Natchez Trace Parkway in Mississippi where his work as a ranger started his career-long interest in reversing trends of inappropriate use of park lands. The Parkway, like LARO, was plagued by its narrow strip of federal land, lack of well-marked boundaries, and multiple encroachments by neighboring landowners. Kuiper worked with the park's neighbors to begin to turn the situation around. After a stint at Blue Ridge Parkway, he served as Chief Ranger at Lava Beds, where relations with the neighboring gateway community were poor. Kuiper liked the challenge of public relations and believed he helped the Park Service there to improve its image within the community. Then, from 1973-1977, he worked as the Assistant Superintendent/Chief Ranger at North Cascades National Park in Washington, where the North Cascades Highway had recently opened. Kuiper then served as Chief Ranger at the Grand Canyon until coming to LARO. "After the hectic life in the Grand Canyon," Kuiper remembered, "I came here and said, 'Is this all there is?' There was nothing in my 'in' box." [23]

LARO staff dealt with two major issues during Kuiper's time at LARO: special park uses and renegotiation of the Tri-Party Agreement. Starting with the 1982 Resources Management Plan, Kuiper and his staff began to identify the underlying problems with special park uses and moved to resolve scores of illegal uses of NRA lands. These efforts culminated in the Special Park Use Management Plan in 1990, LARO's effort to bring the NRA into line with the Servicewide policies of NPS-53. These changes in policy were unpopular with many neighboring landowners who had their long-time permits phased out for docks, buoys, stairways, and lawns. The controversy continued well into the 1990s after Kuiper retired.

|

| Superintendent Gary J. Kuiper, no date. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (file H18 Biographical Data and Accounts, LARO.HQ.ADM). |

While negotiations for a new management agreement were on the back burner during the early 1980s, the three agencies and two tribes actually sat down to talk in October 1985. The next several years were a rocky ride for the Park Service as the parties met periodically to listen to long-standing concerns. Negotiations moved from the local to national level in 1987, and a final round of meetings from 1988 into 1990 resulted in the Lake Roosevelt Cooperative Management Agreement, also known as the Multi-Party Agreement, signed on April 5, 1990.

Superintendent Kuiper was actively involved in the negotiations for the new agreement, but the primary negotiator for LARO was Kelly Cash, Assistant Superintendent. The park added this position in 1983 at the request of Regional Director Jim Tobin, and Cash filled it until his retirement in January 1995. His early career had been at Shasta Lake NRA. He then transferred to the Department of the Interior in 1968, working as a management intern in Washington, D.C. He followed this with assignments as a recreation planner in regional offices in San Francisco and Seattle. Cash then served as a Division Chief for Water Resources and, later, as Chief of Planning for the Pacific Northwest Region. After coming to LARO, Cash helped develop and implement policy on special park uses, in addition to his key role in negotiations for the Multi-Party Agreement. Kuiper came to count on Cash's good legal mind and clear grasp of policy for drafting a wide variety of documents. [24]

One of the most striking features of Kuiper's term as Superintendent was the dramatic rise in visitation that occurred in the late 1980s. The totals rose from just over 500,000 in 1985 to more than 1.7 million in 1991. This placed a strain on staff and facilities, made even more acute by the lack of budget increases. LARO received a base funding increase for the FY1985 budget but no further increases during the period of rapid growth, causing the NRA in 1989 to cut all funding for seasonal lifeguards, cancel some interpretive programs, and close the Fort Spokane visitor center one day each week. Congressman Tom Foley helped secure an additional appropriation of $570,000 for LARO for 1991, bringing the budget to over $2 million for the first time. The extra monies were earmarked for additional staff ($300,000) and for retrofit design work for boat launches to accommodate fluctuating lake levels ($270,000). Growth at the park had finally caught the attention of Congress and the Park Service, and LARO budgets increased to more than $2.5 million during CY1993. [25]

Gerald W. Tays arrived at LARO in July 1993 to take over as Superintendent after Gary Kuiper's retirement from the Park Service in April 1993. Following graduation from the University of Maine with a Master's degree in geology, Tays taught school in Switzerland for a year. He began his career with the Park Service in 1968, working at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area until transferring to Yellowstone in 1972. A meeting with Park Service Director George Hartzog led to Tays' transfer to Washington, D.C., where he worked in the Office of Legislative and Congressional Affairs for five years. During the last two years in the capital, he served as Executive Assistant to Gary Everhart, the director of the agency, tracking legislative issues and advising Everhart on legislation. After leaving the capital, he served three years as District Ranger at Mount Rainier and three years as District Manager at Marblemount in the North Cascades. Tays then went to Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, where he served as both Assistant and Acting Superintendent. He returned to WASO in 1988, where he helped reestablish the Office of Legislation after it had been dismantled under Secretary of the Interior James Watt. Tays worked there for five years before transferring to LARO in 1993 to become Superintendent. [26]

Two critical issues, special park uses and management of cultural resources, had been heating up at LARO prior to Tays' appointment. During his tenure, however, a number of factors converged to create a contentious situation that contributed to his removal as Superintendent. The controversy over special use permits dated from Kuiper's term, when LARO instituted its Special Park Use Management Plan that mandated the eventual removal of all private docks on Lake Roosevelt. Some permittees vocally opposed these changes. During this same period of time, the CCT and STI had assumed responsibility for archaeological surveys on tribal lands within the Reservation Zone. When they tried to extend this to Park Service lands that encompassed their area of traditional use, Tays insisted that the tribes meet professional standards, as specified in the Archaeological Resources Protection Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and follow the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act.

The tribes resented Park Service demands and found common ground with local county commissioners who wanted greater influence over management decisions at Lake Roosevelt. While their concerns were quite different, they agreed that Superintendent Tays, with his insistence on following federal law and Park Service regulations, was a roadblock to resolving these issues. They joined forces to generate political pressure to bring change to LARO, voicing their concerns to both the Park Service and their representative to Congress. The congressional delegation was already well aware of tensions at Lake Roosevelt from several years of constituent complaints over special park uses. In March 1996, the Park Service decided that Tays could no longer be effective as Superintendent at LARO and transferred his position to the Seattle Support Office, working under Deputy Field Director William Walters. The Park Service then re-assigned Tays, under the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, to work with Washington State Parks in Olympia. He retired from the Park Service two years later and signed on with State Parks, first as a volunteer and then as an employee to begin a new program of historic preservation. [27]

The issues that led to the removal of one superintendent did not go away and soon faced Vaughn L. Baker, who was appointed Superintendent at LARO in 1996. After graduating from Montana State University with a degree in earth sciences, Baker took a job with the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. He then transferred to the Bureau of Land Management and finally to the Park Service. His first Park Service job was at the Alaska Regional Office in 1984, followed two years later by a position at Wrangell-St. Elias in Alaska. In 1989, he was appointed Assistant Superintendent at Mammoth Cave where he stayed until taking a position at WASO in 1992. He then served as Assistant Superintendent at Shenandoah from 1994-1996. Baker was asked to take the position of Superintendent at LARO in 1996 and was able to move laterally into the job. [28]

Baker had some serious public relations issues to deal with as soon as he arrived. When he talked with others in the area, he found that relations between the Park Service and surrounding county and tribal governments were "pretty strained." In addition, he found the LARO staff "fairly demoralized . . . , especially at the management level." Baker and the Park Service decided that the best way to begin to deal with the ongoing controversies at LARO was to update the 1980 GMP, a move that had been recommended during an Operations Evaluation in 1994. Senator Slade Gorton earmarked $180,000 in the FY1997 budget to begin two years of planning. "We needed a process to re-engage everybody," said Baker, "and the planning process was the way to do it." The Park Service invited the tribes, various state and federal agencies, county and city governments, conservation groups, citizens groups, and individuals to participate in the GMP planning. [29]

The draft GMP was essentially done "in house." The primary responsibility fell to a Park Service planner, Harold Gibbs, who came from the DSC to LARO for the two-year process. Baker believed that having Gibbs live in the area would enable him to get to know the staff and the many other players at Lake Roosevelt while still having the support of the Denver office. The new plan classified all the lands around the lake into Management Areas and specified the type of development allowed. In addition, it reviewed the controversial issue of special use permits, most of which were phased out by that time. The idea proposed in the draft GMP for community access points, in lieu of private and community docks, was a new approach to this contentious issue that offered the potential to solve complaints about lack of access. In addition, such access points would lessen the Park Service's responsibility for building and maintaining public lake access. If approved, community access points would not go into effect until 2001. After numerous public meetings to discuss the draft GMP, Baker believed the process had helped address many concerns. "We weren't able to necessarily do what people thought we should do," said Baker, "but I think at least people by and large feel they . . . were heard." [30]

The controversy over phasing out special use permits, especially docks, has largely died out during Baker's administration. He and his predecessors shared the same Park Service guidelines, particularly NPS-53, but they differed some in their approach to enforcement. "A lot of this requires having great patience," noted Baker. "You always try to get people's cooperation." For instance, in 1996 eleven of the fourteen owners due to remove their private docks chose to cooperate with the Park Service. "That's pretty good," remarked Baker. Another owner went to federal court where his case was dismissed in September 2000, ending the uncertainty surrounding the remaining two docks. Similarly, the concern over cultural resource management has lessened as the Park Service found ways that Baker believes meet the intent of the laws through working with both tribes. [31]

By the late 1990s, LARO was once again feeling the pinch of a tight budget. The park had received no base funding increase since FY1995. Within two years, LARO had to cut some popular interpretive programs, and the draft GMP in 1998 noted that lack of money led to the staff being spread too thin, as well as reduced maintenance, decreased ability to protect resources, fewer programs for visitors, and reduced visitor safety. The park base was $3,321,000 in FY1998, and LARO was given a park increase in FY2000 and FY2001 to be used for protection of archaeological resources. The NRA receives additional income each year through its designation as a fee demonstration area. It collected approximately $320,000 in fees in 1999 and was allowed to keep close to 80 percent, providing extra funds for projects such as expanding launch ramps, improving accessibility in rest rooms and rehabilitating picnic shelters. [32]

Staff Reorganization

Over the years, there have been various reorganizations of the staff at LARO, primarily reflecting changes in emphasis within the National Park Service. For instance, the ranger and interpretation divisions merged in 1969 to form the division of Interpretation and Resource Management. This divided once again in 1977 to form two new divisions: 1) Visitor Protection and Resource Management and 2) Interpretation and Visitor Services. The interpretive staff position was converted at this time to Chief of Interpretation. This change followed the trend in the Park Service during this period away from the old-style rangers, who performed a wide variety of tasks, to specialists trained for more particular duties. Continuing this trend, LARO reorganized the Ranger Division in 1990 to form a separate Division of Interpretation. The park hired its first Interpreter for the South District in 1991. LARO also worked to create a new Resources Management Division during this time. It began with a Natural Resources Specialist trainee in 1990 who, two years later, became the Resources Management Specialist in charge of both natural and cultural resources. LARO hired the first Archeologist in 1993 and the following year moved all into the new Division of Resources Management. [33]

During the mid-1990s, efforts to cut the size of the federal bureaucracy led to a major reorganization of the National Park Service. The former Regions were consolidated into larger Field Areas that, in turn, were broken into "Clusters" where management was directed by committee. LARO became part of the Columbia Cascades Cluster, with the System Support Office in Seattle. It, in turn, was part of the Pacific West Field Area, with headquarters in San Francisco. Several LARO employees began serving on the advisory committee. A result of this reorganization and downsizing was that individual parks took over a number of functions that the regional offices had done in the past. One of these with critical implications for LARO was the transfer of responsibility for compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act to the park Superintendent. [34]

Concurrent with this overall reorganization of the Park Service, LARO underwent a major park reorganization in 1994. Early that summer, a scaled-down Operations Evaluation emphasized the areas of Administration, Concessions, and Interpretation. The Park Service was particularly concerned with the traditional park organization that they believed encouraged thought and actions along division lines. To counter this, the evaluators recommended increased emphasis on teamwork to break down divisions and improve communications. They suggested reassigning some duties to free administrative staff from various clerical functions. In addition, they recommended combining similar functions into one position, along with adding "interest and complexity" to support positions within the districts. In the area of concessions, the evaluators stressed the need for a new GMP to help the park assess the rapid growth and ensure that any development plans were well conceived. Finally, the team praised the "impressive changes" made in the interpretive program but emphasized the lack of understanding among park staff over the role of interpretation in a recreational park. They recommended development of a five-year Interpretive Plan. The evaluators ranked LARO's management of facilities and grounds as "outstanding." [35]

The results of the Operations Evaluation led to a considerable reorganization within the Division of Administration. LARO consolidated the administrative workload, assigning these tasks to the lowest possible level within the organization. It also placed all administrative positions within the park into the Division of Administration, redescribing and upgrading many of these jobs. The end result was a Chief of Administration who supervised a team of specialists and support staff at Headquarters and two Administrative Technicians in each district. With the retirement of the Assistant Superintendent in 1995, this position was discontinued and replaced with a Civil Engineer assigned to the Maintenance Division. In addition, LARO upgraded four Subdistrict Rangers, two District Rangers, and the Chief Ranger to fully implement the Ranger Careers initiative. The park also reorganized its original three districts (Kettle Falls, Fort Spokane, and Coulee Dam) into two, with the North District office at Kettle Falls and the South District office at Fort Spokane. [36]

Diversity in the Workforce

With LARO adjacent to two Indian reservations, the Park Service was aware early on of the good potential for diverse workforce. Seasonal labor positions initially offered the best opportunity for employment with the agency. Don Everts, long-time LARO employee, remembered many tribal members who worked with maintenance crews throughout the park, with many concentrating on the lakewide debris cleanup. He also recalled Superintendent Wayne Howe saying that he would not look for minorities outside the region when he had two reservations with available labor next door. Indeed, Howe hired two Indians for permanent staff positions by 1972, using the provision for Excepted Appointments as suggested by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). [37]

LARO began keeping count of women and minorities in its workforce at least by the late 1970s. For instance, in 1978 LARO hired thirty-two seasonals in Maintenance, including six American Indians (two women and four men). Another Indian man and an Asian woman worked as seasonal rangers that year. In addition, the park was making a special effort to do business with minority-owned firms. To increase employment of tribal members, LARO began making personal contacts with the CCT, the STI, and the American Indian Community Center in Spokane at least by 1979. These contacts expanded in 1983 to include the Yakima Tribal Employment Office. Although the seasonal labor force included both women and minorities, all nine vacancies for permanent positions in 1981 were filled with non-minority men. [38]

During the mid-1980s, the Park Service once again looked into ways to use Excepted Service Appointing Authority to provide Indian preference at LARO. Because this could be used only for jobs related to providing service to Indians, LARO calculated that it could justify using the authority to hire three seasonal employees. By 1992, however, the Office of the Solicitor restricted this authority to the BIA. The Park Service encouraged its units to convert any Indians hired under Excepted Service to career service if the individual had worked three continuous years and had a satisfactory record of work. LARO hired a seasonal interpreter from the CCT in FY1993, sharing the cost equally through the Job Training and Placement Act. The success of this appointment encouraged the park to pursue a similar agreement the following year with the STI. In 1995, Superintendent Tays tried to fill the vacant Chief of Interpretation position with a highly qualified woman who was a CCT tribal member; he was disappointed, but not surprised, when she accepted a much better offer from the private sector. Late in 1997, LARO developed additional strategies to increase the diversity of its seasonal workforce, based on a full range of demographic variables. The park planned to use the Veteran's Readjustment Appointment Authority and Contiguous Area Appointment Authority to supplement established Park Service hiring practices. In June 2000, LARO hired Frank Andrews as the Team Leader for Planning and Resource Management. Andrews, a Colville tribal member, had worked for the BIA as an environmental protection specialist in Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. He became the first local tribal member to hold a management level position at LARO. [39]

VIPs, SCA, and YCC

The National Park Service uses several programs to provide supplemental labor at park units nationwide. One of the most popular is the Volunteers in Parks (VIP), established in 1970. Although the intent of the program was to augment the services normally provided, VIPs frequently perform ordinary Park Service duties, especially in interpretation. Such volunteers help the agency deal with inadequate budgets and staffing. LARO had a VIP program at least by 1972, when volunteers led campfire programs and helped run the information desk. The program has grown over the years, benefiting the park in many ways. During 1981, volunteers worked nearly 1,400 hours for a total park expenditure of not quite $700, or less than fifty cents per hour, "a genuine deal for us and a good experience for the volunteer." [40] By 1982, VIPs worked as campground hosts in addition to interpretation. The park estimated that the twenty-nine volunteers in 1985 donated nearly $35,000 worth of labor. [41]

The Student Conservation Program (later Student Conservation Association, or SCA) was established in 1957 to help supplement staff in National Park units and other federal lands. With just a couple of pilot projects initially, the program expanded to fourteen parks by 1969. LARO had a student volunteer by 1990 who worked in the interpretation program at Fort Spokane. In subsequent years, SCA volunteers have worked also in resource management. [42]

The SCA served as a model for the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC), a program for teenagers. LARO hosted its first YCC camp in 1977 and the program, while small, has continued every year since. That first year, ten enrollees and three supervisors rebuilt the Lava Bluff Trail, built and cleared fire trails, repaired fencing, worked on timber stand improvement, and helped control noxious weeds. The group also constructed a short-lived, tent-frame YCC camp at Coulee Dam. The program expanded to twenty-four enrollees the following year and was complemented with a non-resident Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC), with ten workers. Over the years, YCC and YACC crews have worked on a wide variety of maintenance projects that the regular park workforce would have been unable to complete. Project costs were split evenly between regional energy accounts and LARO. As Park Service funding dwindled during the 1980s, LARO dropped the YACC program in FY1982 and cut back on the YCC in 1985, dropping to between seven and ten enrollees per year. The park added a Native Youth Corps, sponsored by the STI, for 1994; the eight participants worked with the YCC group, concentrating on maintenance projects in the Fort Spokane District. [43]

Radio Communications

Communication has presented a challenge to Park Service staff at Lake Roosevelt since the beginning. Many of the problems stem from the physical nature of the park, a narrow band of land and water stretching more than 150 miles, bounded by hills and mountains. Inadequate budgets also contributed to communication difficulties in this remote area.

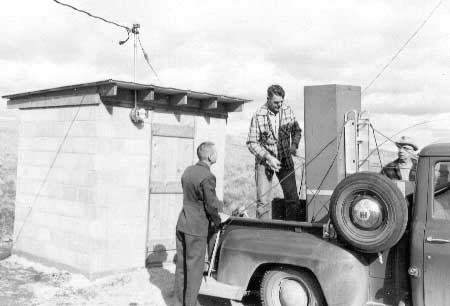

In 1947, Reclamation helped the Park Service install a radio antenna, with two more added the following year. Park Service staff initially maintained a radio room in the Federal Guard building in Coulee Dam but later moved the base station to the North Marina. The equipment was old, however, and in 1950, Superintendent Claude Greider reported that the results remained unsatisfactory after three years of trying to make the outdated equipment work. He decided not to spend any more money or time at that point, preferring to wait for an improved system. That may not have come until 1962 when Superintendent Homer Robinson reported that the park had received $234,298 for a complete communications system. It was to include three base stations, twelve mobile radios, and five portable stations. He believed that coverage should be complete, improving both operations and administration for LARO. [44]

That system was deemed inadequate nearly ten years later due to increasing interference with the radio signal. At that time, Reclamation took care of maintaining the system but did no preventative maintenance. The regional office approved a Project Construction Proposal for a high-band radio system for the entire park in February 1971. Over the next year and a half, representatives from both the Western Service Center and the DSC came to LARO to analyze the park's needs. They recommended a new system with a repeater on Monumental Mountain, southwest of Colville, and a second one in the hills above Jones Bay. Superintendent Burgen submitted justification for the new system in October 1973, saying that the radios were needed to cover the NRA because only five of the twenty-five developed sites had a telephone. Repairs on the radio system in the last fifteen months had cost close to $2,000, causing a great deal of down time. In addition, interference during the critical summer months came from as far away as Arkansas. Don Everts remembered one time when he had tried for half an hour without success to reach Kettle Falls from the south end of the lake. Finally a person who was hearing both sides broke in to ask Don if he needed help in relaying the message. It turned out to be the regional office in Santa Fe, New Mexico. [45]

One of the main improvements in the radio system in the 1970s was the addition of a repeater station within the park boundaries. Because the Park Service lacked the authority to purchase any land, Superintendent Burgen turned to the Mount Rainier Natural History Association for help. In 1974, the Association paid $330 for one-quarter acre of land on the plateau above Keller Ferry and donated it to Reclamation, who then put it under the administration of the Park Service. LARO staff constructed a concrete block building and erected a 160-foot radio tower that year. Reclamation's repeater on Monumental Mountain was "in various stages of obsolescence" at this time, and it asked permission to make a couple of additions to the new Park Service repeater to allow the agencies to share frequencies. Burgen turned down the request, however, saying that the Park Service needed to be able to control confidentiality in its transmissions, a special concern of law enforcement. He offered to occasionally loan portable units to Reclamation instead. Installation of the new radio system, including new base stations and mobile units, continued at least into mid-1975. At the turn of the new century, LARO still maintains a repeater on Monumental Mountain. The other repeater has been moved from Creston Butte to Johnny George Mountain on the Colville Reservation. [46]

|

| Paul McCrary, Homer Robinson, and Al Drysdale installing equipment in the radio transmitter building, March 1961. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

The most recent significant change in the radio system at Lake Roosevelt has been the mandated reduction in bandwidth in all federal VHF radio channels to be completed by 2005. By the summer of 1998, however, all radio equipment at LARO was still the old wideband type and included three fixed-base stations, one mobile base station, nineteen remote-controlled units, one bay-communication console, one commercially powered repeater, three solar-powered repeaters, eight marine radios, forty-five mobile radios, and seventy portables. At that time, LARO staff was interested in cellular phones as possible replacements for the radio system, since close to 75 percent of the park could be reached with cellular service. The park had six cellular phones in 1998 and anticipated increased use in the future. [47]

Staff at LARO have used radios for many purposes over the years. In 1998, there were forty full-time equivalents, twenty seasonals, and ten volunteers who needed radios, with the heaviest use occurring from May through September. First priority was law enforcement, followed by fire protection, maintenance, natural resources, and administration. Law enforcement personnel at Lake Roosevelt needed to communicate not only with each other but also with other law enforcement agencies outside the park. LARO approached the Stevens County Sheriff in 1975 to arrange for direct communication from the park to both the Sheriff and State Patrol. Since the Park Service planned to purchase units for some vehicles that year, LARO hoped to buy ones that would be compatible with nearby agencies. LARO continued to establish cooperative relationships with local agencies during the 1980s, including the Stevens County Department of Emergency Services in 1984, Lincoln County Fire Protection District #7 in 1987, and Stevens County Fire Radio System in 1989. When Reclamation eliminated its dispatch services, on which the Park Service had depended, LARO contracted in 1996 with Lincoln and Stevens counties to take over dispatch full-time. [48]

Computers and Electronic Mail

The advent of computers and electronic mail, or email, changed communications at LARO. Email now supplements telephone communication, enabling staff to send and receive written messages at their convenience. In addition, email within the National Park System has altered communications among parks and regional offices, frequently replacing traditional written communications sent through the postal system.

LARO purchased its first computer, a Datapoint 1800, in 1982. Employees soon developed programs for use within the park. The system expanded rapidly two years later with the addition of a Wang word processing system with terminals in maintenance, administration, and the office of the Superintendent's secretary. The used equipment was acquired from the regional office, saving close to $25,000. The original Datapoint computer enabled LARO to transmit the payroll to the regional office electronically by 1984. The park developed a five-year computer plan that year. [49]

Computers, designed to save time with work, actually led to a backlog of work in 1988. By that year, nearly every office in the park had a work station, and employees all wanted to learn to use the new technology. The administrative staff had gained expertise on computers, mostly outside normal working hours, teaching themselves and others. "We crossed our fingers and forged ahead as a team," wrote Superintendent Kuiper, "sharing knowledge and learning as we progressed." The administrative personnel then spent extra time tutoring other staff, leaving lower priority tasks undone. This caused a backlog of work by the end of the year that the park realized would take considerable time to clear up. Still, they had seven new work stations up and running that year, "thanks to this pioneering spirit!" LARO hired its first computer specialist in April 1991. [50]

Electronic communications within and among offices became available in the late 1980s and 1990s. The Park Service installed SEADOG nodes in three districts in 1989 but still had no way to share data between offices. Instead, staff carried diskettes among the twelve work stations at Headquarters, a method they found "annoying, but tolerable." [51] LARO installed a Local Area Network at Headquarters in 1992 and followed with one in the North District in 1994-1995 and one in the South District in 1996. Electronic mail became available in 1992 at LARO Headquarters and the District offices. A router installed two years later allowed the park to link up with the Department of the Interior network. The router also improved the speed and efficiency of electronic mail between LARO and the Seattle Support Office and enhanced utilization of the budget programs, Federal Financial System and the Federal Pay Pers System. In addition to adding new capabilities to the computer system, LARO upgraded individual computers so that nearly all of the older 286 models had been eliminated by 1995. The park also moved to change all of the technology to work in the Windows-based system, training some of the staff in this program in 1996. [52]

Signs

Unlike many other National Park units, there is no main entrance to LARO. Park Service lands there are confined to a narrow strip on either side of the river, extending roughly 150 miles upriver from Grand Coulee Dam. Visitors reach campgrounds and boat launches on multiple access roads from nearby state highways and county roads. This configuration has made signs particularly important at LARO. The park began working with the Washington Department of Highways in 1974 to erect brown-and-white highway signs to direct tourists to Park Service areas from state highways; installation of these signs was completed the following year, but two years later the state installed another fifty directional signs. Superintendent Gary Kuiper asked for a waiver of rules for highway signs in 1985 to allow listing the full name of the NRA on the Spring Canyon sign, the first one seen by north-bound tourists. He believed this was important because it would alert visitors to the change from Banks Lake, administered under State Parks regulations, to Lake Roosevelt, administered under Park Service regulations. [53]

Initially, all signs within LARO boundaries were traditional wooden ones with routed and/or painted lettering. The park had a sign committee at least by the mid-1960s that inspected all park signs in May. They ensured that the sign was still needed, provided adequate information, and retained an attractive appearance. Any that were deemed unnecessary were removed. Maintenance and repairs were done during the winter months to be ready for the summer season. New signs had to be approved by the committee. [54]

LARO began to switch to metal signs with standardized Park Service symbols in the 1970s at the instigation of Maintenance Supervisor Bill Schieber. The committee completed a Sign Survey and Inventory of existing signs in 1972-1973 and then ordered new signs, made by Federal Prison Industries, through the regional office. Installation of the metal signs did not begin until the spring of 1975, so the park continued to use and maintain wooden signs. In 1976, Superintendent William Burgen complained about excessive delays on sign orders placed through the regional office. When LARO installed new fish cleaning stations that year, the park decided to make routed wooden signs instead of waiting at least five or six months for a sign request to be filled. Burgen noted that if they had sent in a request, they would not have received the signs for the summer season and, moreover, they probably would not have received them in time for the following season. LARO was still waiting for approximately two hundred metal signs in 1977, but it had decided to keep the wooden signs in historic areas to help maintain integrity. [55]

|

| Al Drysdale and James Todd installing new headquarters sign, February 1959. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

There were no major changes to the LARO sign program until the mid-1980s when the park's Maintenance Division photographed and categorized all park signs and entered the information into a computer. LARO approved a Sign Plan in March 1990 to codify the park's approach to signage. It emphasized the need to give entrance signs a friendly, instead of authoritative, tone to welcome visitors. In addition, the plan stressed the need to present a distinct visual image for the NRA within the overall Park Service identity. [56]

Fluctuating Lake Levels

When Grand Coulee Dam created Lake Roosevelt, the United States signed a treaty with Canada confirming that the level of Lake Roosevelt would never rise above the elevation of 1,290 feet. Each year, however, the lake level drops well below full pool, principally during winter and spring drawdowns. This fluctuation in the lake level has presented significant challenges to LARO staff over the years, particularly since the 1980s when drawdowns sometimes have occurred during the summer season. Fluctuating lake levels affect recreation, industry, water quality, aquatic ecology, shoreline erosion, cultural resources, and water supplies.

Many competing interests are factors in determining the reservoir's water level. These include power generation, irrigation, flood control, and, more recently, recreation, fish, and wildlife. In 1948, after extensive regional flooding, the official purposes of Grand Coulee Dam expanded to include flood control. This enabled water managers to draw the lake level down in anticipation of flooding; until the 1960s, however, only the upper thirty feet could be used for this purpose. Reclamation prefers to keep the reservoir full to maximize power production and irrigation potential. The filling and release of Lake Roosevelt is controlled by the Bureau of Reclamation (irrigation), the Corps of Engineers (flood control), the Bonneville Power Administration (power generation), and several other interests (fisheries mitigation). These agencies base decisions on the various authorized uses of the reservoir, annual weather conditions, and thermal plant operations. The National Park Service has no decision-making power over the level of Lake Roosevelt. LARO prefers an elevation of 1,288 feet during the recreation season because this slight drawdown from full pool leaves a small band for retaining stranded debris on shore. It also makes it easier to beach boats and reach the shore from the water. [57]

Current firm constraints on the level of Lake Roosevelt stipulate certain conditions. First, the lake's maximum level is always 1,290 feet, while the minimum level is 1,208 feet except under exceptional circumstances. Second, the maximum draft in twenty-four hours is 1.5 feet to reduce landslide potential. Third, the minimum pool elevation by May 31 is 1,240 feet to provide safe and efficient irrigation pumping to Banks Lake. The Corps and Reclamation signed formal flood-control rule curves in 1978 as part of the Columbia River Treaty. These are used in determining the lake level to store water to meet power generation demands; prevent downstream flooding; and protect anadromous fish by limiting downstream spills that raise nitrogen levels in the water and lead to gas-bubble disease. Increased flows are required April 15 to June 15 for smolt out-migration (this is known as the water budget), which can delay filling the lake until late June or early July. [58]

During the 1940s, when the Problem No. 26 committee was putting together the preliminary plans for recreation on the new reservoir, the various agencies were confident that the reservoir would consistently be at full pool, 1,290 feet, from June to October of each year. All special use permits included a clause stating that the water level of Lake Roosevelt could fluctuate a maximum of eighty feet. The winter drawdown was expected to be to 1,240 feet, perhaps occasionally down as low as 1,210 feet. In fact, from 1941-1951 the drawdown did not exceed thirty feet, and from 1952-1965 it stayed close to forty feet each winter. [59]

|

| Kettle Falls Marina during drawdown, May 1983. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives P222 117 61732, 5-11-83). |

In 1950 and 1951, the Roosevelt Lake Log Owners Association complained to politicians and agencies about the difficulties that fluctuating lake levels caused its members. The thirteen firms depending on Lake Roosevelt for log storage and transportation employed over two thousand workers. The drawdowns, which the association believed were due to "experimental" flood control, affected the Kettle Falls water supply, the few LARO beaches that had been established, log dumping sites, transportation and storage facilities, fire protection, transportation of logs on the lake, and docking facilities. The association reported that 70 percent of all operations on the lake required an elevation of 1,274 feet or higher. It was agreed that either the Park Service (on weekdays) or the Corps of Engineers (on weekends) would notify the association of any anticipated drawdowns that might seriously affect their operations. [60]

Under the terms of the Columbia River Treaty signed in 1961, Canada agreed to provide reservoir storage in exchange for a share of the resulting power benefits at the eleven downstream U.S. power-generating plants. The U.S. also agreed to pay Canada for water storage that helped with flood control in the United States. Canada then built three storage dams and reservoirs to hold flooding spring waters for gradual release later in the year. The new upstream reservoirs were expected to reduce the need for seasonal drawdowns at Lake Roosevelt, but this did not materialize because of the construction of the third powerhouse at Grand Coulee Dam that began in the 1960s. [61]

|

Annual drawdown of the lake from October

through April leaves a wide desolated band of discolored rock between

the shoreline plant communities and low water. An average draft of 40

to 60 feet exposes either vast expanses of sand or steeply eroding banks

at most development sites.

-- NPS, A Master Plan for Coulee Dam National Recreation Area, 1968 [62] |

The third powerhouse affected the elevation of Lake Roosevelt on both a temporary and long-term basis. During the construction of the new plant, Reclamation drew the level of Lake Roosevelt down 130 feet in 1969 and 133 feet in 1974 to allow for dry excavations. Crowds came to view the re-emerged Kettle Falls each time. Since completion of the third powerhouse, Grand Coulee Dam has been used to cover peak loads rather than base loads. This "peaking" caused the reservoir levels to fluctuate more than in previous years. The normal maximum fluctuation in water level each year is now eighty-two feet, although the average is lower. In a typical year, the reservoir is drawn down from January through June in preparation for spring runoff and peak seasonal power demand. It reaches its lowest level during April, and it is generally at full pool between July and December. The Kettle Falls Chamber of Commerce initiated a campaign in the 1960s to maintain high summer lake levels on behalf of recreation on Lake Roosevelt, but this was a losing battle. The drawdowns met complex needs throughout the Columbia River Basin, making their modification unlikely to meet the recreational requirements of one reservoir in the system. [63]

LARO's original recreation facilities were not designed for the large drawdowns that began in the late 1960s. By 1971, however, LARO staff had modified management objectives to include the goal of making launch ramps and docks at selected sites useable during drawdowns of up to fifty feet below full pool. Park staff regularly submitted Project Construction Proposals for extending or building new launch ramps that would be useable at lower elevations. Two new low-water ramps were built in 1974, but few others were funded in the 1970s. LARO staff planned that eventually all the docks would be floating. Until then, drawdowns of just three feet had serious negative impacts on recreation. In 1975, for example, only the floating docks at Spring Canyon were useable between 1,285.5 and 1,288 feet. At that elevation, only four launch ramps were functional, many swim areas could not be used, and none of the fuel docks could be reached by boat. After a public meeting in 1976, Reclamation and the Park Service worked together on a plan to build additional boat ramps and floating gas facilities at various places within LARO. [64]

In the mid-1980s, most of LARO's facilities still had not been adapted to lower summer lake levels. At 1,270 feet, about half the launch ramps were not operational. Below about 1,235 feet, no ramps were useable and most water recreation stopped. Designated swim beaches could not be easily used, and some became dangerous. Some campground water systems were left high and dry, and boat-in campgrounds became unusable. Courtesy docks were stranded on dry land at elevations below 1,280 feet, and many boat harbors could not be reached. Log booms for swim beaches, mooring buoys, and navigational aids had to be moved. Concessionaires' marinas had to be repositioned, making them inconvenient to use and operate. [65]

|

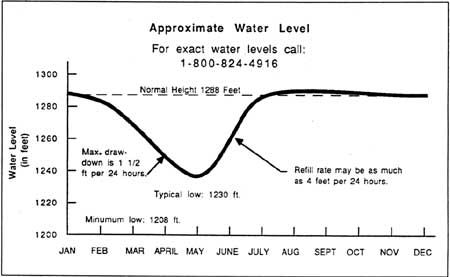

| Typical water levels of Lake Roosevelt over the course of an average year in the 1990s. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake, Southern Part, map prepared by Northwest Map Service, Spokane, 1996.) |

An unexpected drawdown during the recreation season sometimes damages boats and other facilities. Visitation drops, particularly when the media report on the drawdown, and concessionaires suffer economic hardship. This happened in the summers of 1984 and 1985. In July 1984, the lake level dropped to 1,277 feet despite continuing predictions of stable or rising lake levels. This unexpected drawdown was caused by a combination of high power demand, weekend shutdowns of Hanford Nuclear Plant, and poor forecasting. In 1985, the lake was at 1,267 feet in mid-June and it did not reach a pool elevation of 1,288 feet until after September. The concessionaires at Kettle Falls and Keller Ferry were severely impacted, suffering both damaged boats and lowered visitation. [66]

LARO tried to deal with the 1984 and 1985 extreme drawdowns in several ways. Park Service staff established a toll-free telephone number that provided daily lake levels and predictions. They also produced a video with Reclamation illustrating how lake fluctuations impair their ability to serve the public; this led to meetings with BPA in 1986 and the start of an information project. Maintenance staff did extensive work parkwide in 1985 to keep facilities operational, moving swimming areas, adding protective log booms, relocating courtesy docks, installing additional steps and ramps, and moving buoys. LARO also installed elevation markers at various locations around the lake to aid boaters. [67]

Reclamation made some changes in the early 1990s that somewhat improved the fluctuating lake level situation on Lake Roosevelt. In 1990, a new minimum-lake-level limit of 1,220 feet replaced the earlier limit of 1,208 feet, effective except in critical flood-control situations. In addition, Reclamation instituted a costly hard constraint of 1,285 feet by July 1. The agency followed this in 1991 by listing recreation as an "A" priority for the first time ever. [68]

In 1986, the DSC did a full engineering and cost study of the extensive modifications required to make LARO's facilities at twenty-eight developed areas usable by the public at elevations down to 1,270 feet. The DSC found items most affected by the new design level were swim areas and marine access to developed areas. The one-time retrofitting and redesign cost was estimated to be approximately $1.3 million, primarily for labor and materials for new boom floats, extended launch ramps, and revised anchorages. In addition, annual maintenance costs would increase. LARO Assistant Superintendent Kelly Cash put together a project proposal for congressional funding. Then, because BPA was identified as the agency responsible for the drawdowns necessitating the retrofit, the BPA congressional liaison in Washington, D.C., took the proposal to Rep. Tom Foley and others. The resulting funding helped widen and extend seven launch ramps (generally down to 1,267 feet), and built six new ramps in 1993. By 1997, all LARO launch ramps were useable down to 1,282 feet, and some went as low as 1,229 feet. [69]

One of the causes of low summer elevations since 1984 has been the use of water from Lake Roosevelt to help flush anadromous smolt (salmon and steelhead) toward the Pacific Ocean. Starting in 1984, three million acre-feet of Lake Roosevelt water was dedicated annually for spring and early summer salmon flushes. Following the passage of the Endangered Species Act and the 1993 inclusion of Snake River chinook, sockeye, and coho salmon on the endangered species list, an additional 3.5 million acre-feet was dedicated to the flushing project. In July 1994, a drawdown to help anadromous fish caused the lake level to drop below 1,274 feet through early August. As a result, the concessionaire's marina at Kettle Falls had to move its rental docks out of the harbor for the first time during the visitor use season. In 1995, a Biological Opinion allowed as much as ten feet of water to be drafted from Lake Roosevelt, generally in August, to augment flows for downstream fisheries. LARO's 1998 draft GMP noted, "Recreation and fisheries within the national recreation area will continue to be a secondary consideration for the overall operation of the reservoir." [70]

Landslides

Landslides along the shores of Lake Roosevelt were a major problem in the early years of the reservoir when the rising waters caused hillsides to slump. Lake drawdowns continue to cause landslides because the steep, saturated banks become unstable when support from the water in the lake is removed. Waves from boat wakes or high winds also cause shoreline erosion, and other minor factors include heavy rainfall, earthquakes, irrigation of adjoining land, freezing and thawing, building construction, and wedging action by tree roots.

|

| Building a concrete retaining wall at Evans Beach, early 1960s. Gabions and metal-sheet piling have also been used to reduce erosion at developed sites. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Many slides occurred in the 1940s, both as the reservoir filled and after it reached high pool in mid-July of 1942. Perhaps the largest was a 1949 slide in Hawk Creek Bay that created a wave some sixty-five feet high that swept across the lake and continued more than one hundred feet up the opposite bank. All told, about five hundred slides occurred between 1941 and 1953. Sand slides along the lakeshore usually stabilized after one slippage, but slides in silt and clay slid repeatedly. [71]

The Bureau of Reclamation has always had lead responsibility for dealing with landslides and shore erosion along Lake Roosevelt, but it is really a joint concern with the Park Service because landslides directly affect LARO operations. Reclamation policy since the 1940s has been to acquire any lands that are located within potential slide areas that have been or could be readily improved. If landowners are unwilling to sell, Reclamation seeks releases from damages due to slides. Between 1941 and 1969, some six thousand acres of slide-prone land were acquired. For land in potential slide areas within the two reservations, legislation amending the Act of June 29, 1940, allowed the federal government to take such land without challenge. The government did have to pay fair market value, however. Graves from a number of cemeteries had to be relocated in the 1940s and 1950s because they were located in critical slide areas. [72]

Construction of homes along the lakeshore in the 1960s led to higher land values. Reclamation focused on acquiring unstable areas that were most likely to be developed. During the 1970s, the CCT expressed concerns about the Reclamation program to acquire land threatened by landslide activity. They wanted any such lands that had shown no slide activity returned to the tribes. Some people believed that land had been taken under false pretexts. This remained an issue into the 1980s, but Reclamation continues to acquire land in potential slide areas. [73]

LARO's Superintendent and staff were quite involved with the landslide studies of the 1940s because identification of potential slide areas affected planning of recreational areas and issuing of special use permits. As LARO Superintendent Claude Greider commented in 1950, "It is becoming increasingly evident that geological factors are more and more important to our planning program." The Park Service solicited help from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in evaluating areas proposed for major recreational development, summer homes, and industrial or agricultural uses. As a result, USGS, Reclamation, and the Park Service agreed on plans for a multi-year study, starting in 1949, conducted by Fred Jones of the USGS. LARO provided boat transportation for the project. The primary purpose was to understand slide conditions along the Upper Columbia River, but Jones also provided detailed informal reports on specific sites as requested by the Park Service. Discovery of potential slide conditions necessitated new master plans for certain areas, such as Fort Spokane. LARO began to install warning signs in 1951 to alert the public to danger from landslides and to diminish Park Service liability in case a landslide harmed a park visitor. [74]

Although landslide activity decreased after the 1950s, some large slides did occur in later years. In March 1969, a landslide dammed the Spokane River for nearly thirty-six hours. The river rose approximately thirty feet behind the 15 million cubic yards of earth before breaching the dam. This and other slides that year were associated with the extreme drawdown due to the construction of the third powerhouse. Overall slide activity increased between 1969 and 1975 and then tapered off again. LARO's 1968 master plan noted that landslides were still a major planning consideration. Erosion of the lakeshore by wave action also remained a problem at some developed areas and caused many trees to fall into the lake. Reclamation had an ongoing program to stabilize the most critical slide areas. LARO maintenance personnel began measuring all eroding shorelines in major developed areas in 1972 and installed concrete sea walls, gabion bags, or riprap to counteract the erosion process. [75]

|

| Sockemtickem slide near Fort Spokane, April 1969. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

The 1961 Jones report determined the relationship between increasing frequency and magnitude of landslides and increasing severity of reservoir drawdown. It served as a guide for later investigations along the lakeshore. Reclamation initiated annual inspections and photographs of active landslides along Lake Roosevelt in the 1960s. These trips often identified problem areas, such as roads that needed additional marking or berms to prevent traffic in areas with active landslides. A program of selective logging was initiated along the lakeshore to harvest timber within a short distance of the water line. Since the 1970s, Reclamation has tried to avoid creating landslides by keeping the rate of drawdowns less than 1.5 vertical feet per day. [76]

Various experts and officials spent considerable time in the late 1940s and early 1950s studying landslide potential at the landings for the Gifford-Inchelium ferry. This ferry, located 78.5 miles upstream from Grand Coulee Dam, was an important transportation link for Indians living on the reservation. Prior to any landslide assessment, the ferry owner obtained a twenty-year lease from Reclamation in 1941 to operate the ferry and build approach roads over federal land. In 1949, an examination revealed that the approach on the Gifford side (Stevens County) was in a critical slide area. Reclamation believed that the Park Service should help find a new location and that the counties should build and maintain the approach roads between the federal boundaries and the main highway. Fred Jones of USGS proposed possible replacement ferry landings 1.7 miles downstream. Feelings ran high on all sides over the location of the new landings and responsibility for construction of access roads; even the current owner remained undecided about continued operations. LARO Superintendent Greider spent a great deal of time responding to public and agency inquiries about the situation. [77]

The Park Service allowed the ferry to keep operating during the 1950 season while it worked with the operator and other agencies to find a solution. In early 1950, Greider recommended that the ferry be moved to the proposed site 1.7 miles downstream. LARO agreed to build and maintain the sections of the approach roads within the NRA boundaries. The question of who would build the roads between LARO and the main highways, however, was difficult to resolve. LARO maintained it was a county responsibility, but the two counties - and the Park Service Director — believed that Reclamation should do the work since the creation of the reservoir had caused the problem. Having reached an impasse, the Park Service canceled the ferry license at the end of 1950. As expected, county commissioners complained to their congressman about the hardships caused by the closure. Within six weeks, a compromise was reached whereby the existing Inchelium landing was retained and the Gifford landing was moved about one mile downstream to where old State Highway 22 ran into the lake. LARO built an approach road to connect the old and new highways. The ferry service became a public utility operated by the counties involved, under a lease agreement with the Park Service, and the counties assumed all liability. [78]

The seasonal Gifford-Inchelium ferry ceased operations in 1974 because the business was not profitable. As a result, people had to drive an additional one and a half hours to cross the river. The CCT asked Reclamation to operate a free ferry service at the site. As the CCT and BIA solicited Congress for funding, Reclamation provided interim emergency service with a helicopter and radio communications. The Solicitor's Office determined in 1975 that Reclamation was not responsible for the ferry. Instead, the Department of the Interior agreed to fund the ferry, with the BIA taking over operations. The first BIA ferry was a barge and tug loaned by Reclamation, but in 1981 the sixty-passenger Columbia Princess took over the service. In 1994, the CCT took over operation of the ferry from the family that had run it since 1975. [79]

Floating Debris on Lake

Roosevelt

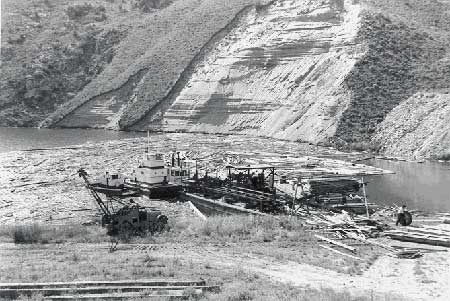

In the 1940s and 1950s, floating logs, trees, and other "woody debris" on Lake Roosevelt caused great concern to LARO and Reclamation staff. This debris was largely composed of logs, snags, and slash from logging operations, as well as uprooted trees and brush from lakeshore erosion that extended from Keller Ferry upstream. After the flood of 1948, the banks of Lake Roosevelt were lined with a band of "trash" as much as fifty feet in width. The debris piled up on beaches, while logs and "deadheads" (logs that have sunk at one end) posed a hazard to small boats and float planes. If the debris were not collected, it continued down the Columbia River and passed over a series of dams. Every year, spring high water brought more from Canada and large tributaries, and the floating debris filled the lake in a solid mass from the dam to above Spring Canyon. Debris cleanup was one of the first activities to receive funding at LARO. [80]

|

| Driftwood on beach, Lake Roosevelt, 1956. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center. |

During years that sawmills were booming and towing logs on the lake, stray logs were also a constant management headache. LARO Superintendent Claude Greider began to address the problem of stray logs and "deadheads" by informing logging operators on Lake Roosevelt that Reclamation would collect loose saw logs floating on the lake. In May 1948, Reclamation began removing stray logs from the lake and its shores. The Park Service regional office consulted with the Director about the possibility of LARO granting a permit to a private individual to boom and take possession of logs in consideration for his agreement to clean up the debris, but ownership questions made this impossible. The Park Service did, however, have authority to remove floating logs and debris from the lake as long as the merchantable timber was returned to the legal owners. [81]

The Roosevelt Lake Log Owners Association, formed in the early 1950s, hired a contractor to salvage loose logs. After just a short time, they terminated the Grand Coulee Navigation Company, the first contractor as well as LARO concessionaire, because of unsatisfactory work. They next hired Hal Marchant, a former LARO maintenance employee, to salvage their logs. This work, while improving the floating debris situation somewhat, did not eliminate all the trash from the lake. [82]