|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 7:

Building and Maintaining the Park: Administrative and Visitor Facilities

The administrative and visitor facilities at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO) range from headquarters to employee housing to a wide range of visitor facilities. Each new building or developed area has required planning, construction, and maintenance. Besides the facilities constructed by the Park Service, concessionaires also provide certain visitor facilities within the national recreation area.

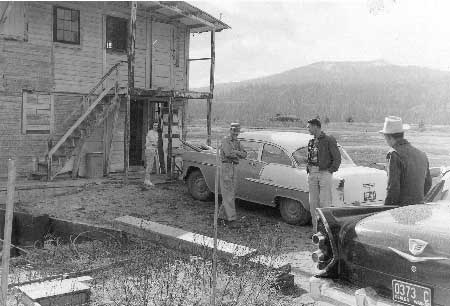

Headquarters

The first official National Park Service facility in the Lake Roosevelt area was workspace for Park Service staff that the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) provided under the terms of the 1941-1946 interbureau agreements. Between 1942 and 1952, Park Service personnel worked out of several rooms on the second floor of a temporary general store building in Coulee Dam, located near today's public rest area. The best location for permanent administrative headquarters was discussed at great length during the 1940s and 1950s. Proposed locations included Coulee Dam, Colville, Fort Spokane, Kettle Falls, Spring Canyon, and South Marina (Crescent Bay). Under the terms of the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement, Reclamation agreed to provide facilities in the Reclamation Zone for Park Service administration of the national recreation area (NRA). In 1947, Reclamation provided LARO staff with a new warehouse, four-car garage, and a small shop building next to the Coulee Dam theater to supplement the existing 600 square feet of office space. Reclamation planned to raze the temporary office building in 1952, so by the late 1940s LARO's Superintendent Claude Greider was searching for funding for the construction of a new building for NRA headquarters. [1]

|

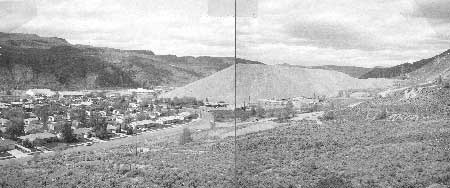

| LARO headquarters (in front of sand pile) and six employee houses on Crest Drive (curved road in fore-ground), 1967. The three houses on the right were constructed in 1966. (File A94 3rd Power Plant: Other Ramifications 1966-76, box 3 of 3, LARO #95, Cat. #3250, LARO.HQ.PAO.) |

In January 1952, the small Park Service staff moved temporarily into the Reclamation field office on the main highway to Coulee Dam. A week later, Greider commented approvingly to the Regional Director that the modern building overlooked Lake Roosevelt, was convenient to the public, and was "all that can be desired." [2] LARO's new offices consisted of three rooms totaling 1,138 square feet. The Park Service paid Reclamation an annual fee for utilities and other services for these and other facilities at Coulee Dam. LARO's stay in this building was short-lived, however. In late 1953 or early 1954, LARO headquarters moved to a building that had been occupied by Reclamation's Parks and Street crew on Crest Drive. The Park Service also used adjacent outside storage space. LARO agreed to maintain the building and Reclamation to provide electricity, sewer and water service, and garbage collection, for which it was reimbursed. [3]

|

| Women landscaping LARO headquarters, 1960s. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

LARO staff continued to examine the possibility of relocating headquarters to a more central location. During the Mission 66 period, LARO personnel favored Fort Spokane, but the Regional Office favored retaining headquarters in Coulee Dam, partly because of the continuing possibility of LARO taking over the administration of recreation on Banks Lake. In the spring of 1959, as part of the privatization of the town of Coulee Dam, LARO received jurisdiction and control over the headquarters building on Crest Drive and an adjacent 5.7 acres of land. The Park Service paid Reclamation over $93,000 for the administration building and almost $37,000 for a garage and shop in Coulee Dam. LARO used Accelerated Public Works money in the fall of 1962 to convert the attached glass greenhouse into 2,250 square feet of additional office space. [4] This complex still serves as LARO's administrative headquarters.

Employee Housing

Housing for LARO employees was first provided in the town that is now known as Coulee Dam. This community was constructed in the 1930s as Mason City, headquarters for the Grand Coulee Dam contractors. Residences, barracks, businesses, a high school, and dining halls were built almost immediately. Across the river was Engineers Town, a showplace government town for Reclamation engineers that is now the western section of Coulee Dam. From the start, Mason City was heated only by electricity. When the dam was completed and the contractors moved out, Reclamation took over Mason City. [5]

In the 1940s, when only a handful of Park Service personnel worked out of Coulee Dam, Reclamation used a point/drawing system to allot housing in Coulee Dam, based on seniority, size of family, rank, years of service, and other factors. But Frank Banks of Reclamation did manage to save a "choice" residence for Claude Greider, the Park Service Recreation Planner assigned to live at Coulee Dam in 1941. According to the 1942 Reclamation/Park Service agreement, however, other Park Service employees had to "take their chances" through the point system for their living quarters. In other words, they were given no assurance of being able to obtain government housing. By 1948, Greider was complaining that the houses provided in Coulee Dam by Reclamation were inadequate, and he included proposals for eight residences and five apartments for employee housing in the recreation area's 1948 Master Plan. Reclamation agreed to reserve vacant lots in Coulee Dam for Park Service employee housing. [6]

In 1950, Congress appropriated $48,600 to construct three five-room dwellings in Coulee Dam for Park Service housing, and they were completed that December at 606, 608, and 610 Crest Drive. The occupants paid Reclamation for utilities plus an annual charge for amortization of Reclamation's investment in municipal improvements. Some locals strongly criticized the construction of Park Service housing before recreation sites had been developed. For example, the manager of the Grand Coulee Navigation Company, a LARO concessionaire, commented in 1951, "There is a strong and growing feeling among the people of this area that their tax money is being used to provide salaries and superior living quarters for government employees rather than for development of a recreational area to the benefit of the public." [7]

The town of Mason City (Coulee Dam) declined in population in the early 1950s as Reclamation converted from dam construction to long-term operation and maintenance. In 1953, a study recommended that the 450 federally owned temporary houses and the shopping center be sold to the residents. Congress authorized the conversion from government town to self-governing community in 1957, and the sale was essentially completed the following year. The Park Service, of course, was concerned that it might lose its three new houses and the use of three Reclamation houses rented by LARO employees. In 1959, Reclamation transferred to the Park Service the three lots with Park Service houses plus two Reclamation houses that were already being used by Park Service employees (425 and 804 Yucca). In addition, four permanent Park Service employees owned their own homes in Coulee Dam. LARO acquired ten town lots for future residences in Coulee Dam in 1960, probably as a no-fee transfer from Reclamation. [8]

|

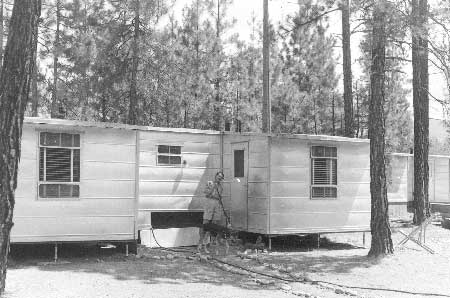

| Transa-house for seasonals at Kettle Falls, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

The challenge of providing housing to employees subject to frequent transfers continued in the 1960s. The volatile housing market in the general Lake Roosevelt region hindered LARO's planning efforts to meet housing needs. The construction work on the third powerhouse during this period led to the removal of nine businesses and fifty-seven residences in Coulee Dam; housing once again grew scarce. The Park Service built three new residences in Coulee Dam in 1966. The three Park Service houses on Crest Drive built in 1950 were located within the Reclamation "taking line" and were scheduled to be moved in 1968. LARO Superintendent Howard Chapman wrote, "I believe we should not be stampeded into moving without a careful appraisal of the situation." In the end, however, the three older houses and one other were moved to new locations in Mason City. LARO turned the three houses built in 1950 plus the one at 804 Yucca over to the Bureau of Indian Affairs between 1983 and 1994. [9]

Outside of Coulee Dam, the housing situation for LARO employees was "most unsatisfactory" in the 1950s, according to LARO's Mission 66 Prospectus. No housing in the Fort Spokane area was available, and there was an acute shortage of housing in Kettle Falls. In 1957, LARO installed three "transa-houses" (small, modular frame houses) at Fort Spokane and one portable building and two transa-houses at Kettle Falls so that seasonal and permanent employees could live close to their work sites. The nationwide trend towards standardized Park Service residences did not affect LARO employee housing until 1962, when two standard Mission 66 residences were built at Fort Spokane. [10]

By 1963, LARO's employee housing situation had improved somewhat to include nine permanent and fifteen temporary quarters. The rates charged the occupants were based on rents charged in Omak, Colville, and Spokane. LARO administration continued to work on obtaining more housing for the growing staff. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Columbia Basin Job Corps out of Moses Lake built portable seasonal quarters for LARO employees at all the major campgrounds, replacing some seasonal trailers and the transa-houses. A new seasonal housing area at Fort Spokane was established in 1973. By 1979, employee housing had increased to eight houses at Coulee Dam, five at Fort Spokane, and five at Kettle Falls, plus fourteen trailers at seven sites. In general, maintenance staff was hired locally and did not require housing, and seasonal employees were often unmarried and could live in shared housing. [11]

|

1996 Employee Housing at LARO:

Coulee Dam — 3 permanent houses, 1 seasonal trailer Spring Canyon — 1 seasonal house, 2 seasonal trailers Keller Ferry Campground — 1 seasonal house Fort Spokane — 3 seasonal houses, 2 seasonal trailers, 2 permanent houses Porcupine Bay Campground — 1 seasonal house, 1 seasonal trailer Hunters Campground — 1 seasonal trailer Kettle Falls area — 2 seasonal trailers, 2 permanent houses, 1 seasonal house Evans Campground — 1 seasonal house [12] |

During the 1980s, LARO formalized its planning for employee housing by preparing a Housing Management Plan. Quarters continued to be added and subtracted; for example, two permanent quarters in Coulee Dam were surplused in 1985 as part of a plan to reduce housing at headquarters. In 1986, as the result of an analysis showing that seasonal rents did not even cover the cost of utilities, all rates were recalculated and increased. In 1988, the annual rents ranged from $4,212 for a Fort Spokane house for a permanent employee to $460 for a trailer for a seasonal at Hunters. A 1993 rent appeal by employees living in government housing in the Fort Spokane District resulted in refunds to fourteen LARO employees. The appeal was based on the assertion that rents should be based on those in the nearby Davenport area rather than the Spokane metropolitan area. [13]

Because of the short season and the difficulty in obtaining rental housing locally, LARO felt that providing housing was critical to recruiting seasonal employees. From the end of the Mission 66 program in 1966 until 1988, no significant funding was available for Park Service units to build or rehabilitate employee housing. Starting in 1989, however, the Park Service received funding through a Housing Initiative for major rehabilitation and trailer replacement along with line-item funding for construction of new or replacement housing. LARO established partnerships with the Park Service's Rocky Mountain System Support Office and the Washington, D.C., Office in 1996 to obtain designs for a four-bedroom dormitory and a duplex. By the late 1990s, LARO policy emphasized providing park housing to seasonal workers, and one of the park goals was to remove, replace, or upgrade to good condition employee housing classified as in poor or fair condition. The last trailer at LARO was removed in 1999. [14]

With sixteen houses and eight mobile homes in 1988, LARO staff felt no additional housing was necessary. With the exception of certain employees who had to occupy government housing in order to provide visitor services and to protect government property, all other LARO employees were assigned housing under competitive bidding using a point system based on salary, number of dependents, and years of government service. LARO staff preferred to retain three houses in Coulee Dam while they evaluated the impact of the anticipated rapid expansion of concession operations at Grand Coulee and Keller Ferry. In response to Congressional concerns in the mid-1990s about the Park Service housing program, housing built for permanent employees' use was re-designated for use by seasonal employees as the units were vacated. The park is trying to keep a permanent employee in residence at Fort Spokane grounds to address visitor and resource protection concerns. [15]

Roads

When LARO was established in 1946, a number of roads already existed within the NRA. As is true today, state and county highways paralleled the lakeshore and provided the major access and approach roads to Lake Roosevelt. LARO employees have been concerned primarily with the access roads that lead to the park's developed areas. Park Service staff in the 1940s felt that the construction of approach roads to recreational sites was of primary importance to developing the NRA, partly because good access roads would allow concessionaires to develop particular sites. As soon as funding was available for construction, in 1950, the roads to the Kettle Falls, Fort Spokane, and North Marina recreation areas were improved. By the late 1950s, LARO had some twenty-seven miles of primary and secondary roads within the NRA boundaries. Most were graded and graveled to a minimum standard "to preserve the primeval effect of the shoreline," [16] but those in areas of heavy use were paved. LARO also maintained many spurs, loops, parking areas, interchanges, and terraces. [17]

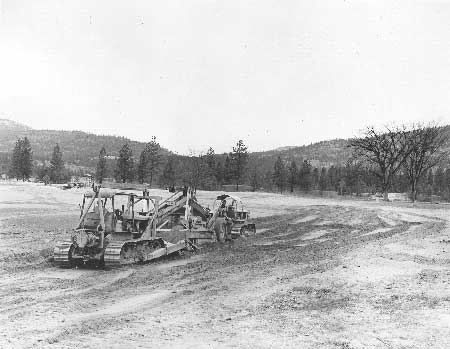

Mission 66 proposals related to LARO's roads involved improving existing roads and building new roads to provide access to proposed new areas. Some seventy-three new miles of roads were proposed to be added to the existing twenty-three miles under the roads and trails budget of $90,000. In some years of the Mission 66 program, road improvements were the largest item. LARO maintenance crews maintained the roads within the NRA, and local, state, county, and city crews worked on the roads on an equipment-rental basis. One of the on-going jobs was making sure that old roads that ran right into the reservoir were well marked or barricaded. During the 1970s, routine maintenance work continued with re-surfacing and grading roads and parking lots. The roads in the NRA have not yet reached the levels anticipated in the Mission 66 prospectus; as of 1994, the total road mileage was sixty miles, of which twenty were abandoned roads. [18]

LARO prepared a preliminary inventory and survey of needs for roads within the NRA in 1980 that provided sufficiency ratings compared to national standards. The Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982 authorized the Federal Lands Highway Program to implement phased improvements of Park Service roads. As a result, the Park Service conducted Servicewide transportation planning for all public use and administrative park roads. LARO maintenance staff worked with the Denver Service Center and the Federal Highway Administration on an updated road inventory and needs study, campground road classification, and road improvement study. The resulting report concluded that LARO's roads were generally in fair to good condition, despite some deficiencies, and it made specific recommendations for construction and maintenance projects. [19]

Road maintenance equipment at LARO in 1980 consisted of three 2-1/2-ton trucks, one backhoe, and two tractors. Maintenance crews at that time spent 2 to 5 percent of their time on road maintenance. The work included mowing the roadsides, repainting traffic stripes, plowing snow, irrigating several locations, and picking up litter along roads. [20]

Increased visitation beginning in the 1970s led to visitors venturing into previously little-used areas of LARO, many driving off-road vehicles (ORVs). Old farm and logging roads were opened up, and new trails were created to access the land exposed during the winter drawdowns. Some visitors destroyed physical barriers in order to access particular spots. This spread-out use created problems with sanitation, fires, soil erosion and compaction, disturbance of wildlife, damage to cultural resources, and noise (particularly in the Crescent Bay Lake area). [21]

Executive Order 11644 (Use of Off-Road Vehicles on Public Lands) issued in 1972 directed federal land-managing agencies to develop regulations and designate areas of use for ORVs. In 1974, the Park Service closed all National Park System areas to ORV use except those specially designated as open by Federal Register notice or special regulation. In 1980, LARO employees installed about three hundred barrier posts, and the following year LARO rangers instituted special measures that were only partly successful to control the use of unauthorized roads by ORVs. LARO's 1982 Resource Management Plan identified ORVs as a major management problem and recommended a survey, policy development, barricading of sensitive sites, and restoration of damaged areas. In 1982, a survey recorded over fifteen kilometers of unauthorized roads in the Fort Spokane district, most accessible by two-wheel-drive vehicles from public road systems and not associated with ORVs. The survey provided a method for classifying LARO's roads, and it resulted in the closure of many of the unauthorized roads in that district. [22]

One area that received special attention was Rattlesnake Canyon east of Crescent Bay Lake, where motorcycles and ORVs were causing erosion and noise pollution. In 1982, LARO and Reclamation banned ORVs from the area. Although LARO staff prepared draft ORV regulations in 1982, they proved controversial and were not enacted. Instead, staff recommended a review of the current status and preparation of a management plan that would designate ORV routes as required by the 1972 Executive Order. Finally, in 1992, LARO established a new policy restricting motor vehicles to established roads within the NRA and specifically prohibiting their use in drawdown areas. This decision was made primarily to protect archaeological sites. Two years later, the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) also restricted non-member ORV use, including snowmobiles and dirt bikes. Regulating ORV use is not currently a significant issue for LARO's law-enforcement personnel; the problems are small in scale and mostly occur during drawdown periods. [23]

Owners of land adjacent to certain roads within the NRA have requested easements for access roads over the years. One example is the road to the Spring Canyon developed area. In 1952, the Julius Johnson estate gave land for this road and other purposes to the Park Service, and the road was constructed a couple of years later. At least one person was given verbal approval for infrequent access to his land from the road for agricultural purposes. In 1986, several requests were made for residential access from the road to proposed subdivisions. The Park Service opposed all these requests because they believed that other practical access routes existed and because they did not want to grant an easement and set a precedent. In the early 1990s, LARO formalized its easement policy by stating that no new roads would be considered for easement recommendation to Reclamation; that any easements had to remain open to the public; and that adverse impacts to the NRA must be minimal or non-existent. Some easements were granted on roads predating the acquisition of the lands by the federal government and in cases where the Park Service had made previous commitments to provide easements. [24]

Until recently, the Park Service was not authorized to participate financially or otherwise in road maintenance projects on roads outside the NRA boundaries. This has led to some difficulties at LARO. For example, in the 1980s many residents along the county road between Laughbon's Landing and Porcupine Bay, built by a developer, complained about the dust generated along the gravel road. LARO and Lincoln County and the homeowners all agreed the road should be paved. County commissioners were unwilling to spend money on the road because a very high percentage of the traffic consisted of Porcupine Bay campground users. Eventually, however, the county did pave the road. [25]

Trails

|

Due to the large water area and small land

base, we have not developed a major emphasis on trails. . . . The

southern half of the lake is quite dry and hot with limited hiking

interest even though I find spring and fall very pleasant to kick around

in the sagebrush. (Snakes are somewhat of a deterrent!)

-- Jerry Rumburg, LARO Chief of Interpretation, 1981 [26] |

LARO has not developed an extensive trail system, primarily because the NRA consists of a narrow strip of land along the shores of Lake Roosevelt and is not particularly conducive to hiking. The Mission 66 prospectus for LARO proposed a lakeshore foot trail running the entire length of the lake with layover points and shelters spaced a day's hike apart, but this has not been constructed. In 1972, LARO had only one trail more than one mile long: the self-guided interpretive trail at Fort Spokane. LARO considered constructing a nine-mile trail between Fort Spokane and Porcupine Bay in 1979, but this was never built. A number of trails were constructed in the 1970s, so that in 1980 LARO had six trails totaling 3.83 miles: Bunch Grass Prairie Nature Trail, Lava Bluff Trail, Fort Spokane interpretive trail, Fort Spokane campground trail, Kettle Falls interpretive trail (connecting campground and beach), and St. Paul's Mission trail. Of these, the Fort Spokane interpretive trail was the most popular, with highest daily use in 1979 of sixty-five visitors. By 1987, LARO had nine miles of trails. [27]

|

| Constructing a trail at North Marina, 1963. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Sewage Disposal and Electric

Lines

In 1943, when Park Service personnel were preparing the layouts for various recreation sites along Lake Roosevelt, the Regional Engineer commented that sewage disposal was probably the greatest technical problem the Park Service would face. He recommended locating comfort stations high enough so that the necessary drop in elevation to disposal fields could be provided. The initial sewage facilities at LARO were septic tanks/leach fields for buildings and pit toilets. [28]

A good example of LARO's creative re-use of surplus materials was the conversion of short-term air-base runway landing mats into liners for outhouse pits. Maintenance workers stored "tons and tons" of these 14-inch-wide interlocking mats at the yard at headquarters, according to former LARO employee Don Everts. They welded them together to form boxes. The mats were pierced with holes that were "about the size of a coffee cup. There was enough to keep the solids in and the fluids would run out." Everts noted, "It made a real good pit. . . . .You just dropped them in the hole with a backhoe and backfilled it and there you had it." Unlike wooden pit liners, which rotted quickly, these steel liners lasted virtually forever. The recycled mats worked well in LARO's many outhouse pits until the Mission 66 program called for the replacement of pit privies with vault toilets. [29]

As visitation to LARO increased in the 1970s and 1980s, so did problems associated with sanitation. Assistant Superintendent Kelly Cash quipped in 1989, "People are camping on beaches. Human waste is a problem. On some of the beaches, it looks like a Kleenex factory has exploded." [30] By the 1980s, most of LARO's pit toilets had been replaced with vault toilets, and several comfort stations had running water.

Campers on beaches without sewage disposal facilities are required to bring portable toilets with them. Today, sewage is not a significant problem at LARO. [31]

In the early 1970s, LARO used Regional Reserve funding to convert some of its overhead power lines in developed sites to underground, in accordance with Park Service policy on utilities for recreation areas. This costly project to improve the appearance of the sites was mostly done by contractors. LARO's 1990 Special Park Use Management Plan required all existing electric lines to be underground within the NRA. This raised concerns with local electrical utilities. All or almost all the lines are now underground within the recreational area boundaries. [32]

Trash and Hazardous Materials Disposal

Trash disposal by visitors, both on water and on land, was another important concern at LARO in the early years. The general practice in the 1950s was to put garbage in a sack and toss it into the deep waters of Lake Roosevelt (LARO Superintendent Greider recommended taking the trash ashore and burying it). By 1963, LARO employees were collecting some 26.5 tons of garbage per week from the various campgrounds. Trash was disposed of by burning in incinerators or disposal in landfills. Some campgrounds had sunken-barrel trash containers in which the garbage was periodically burned. In 1976, a Park Service directive instructed all units to attempt to have all solid waste disposed of outside the park by private contractors, giving preference to sanitary landfills over incineration. LARO's maintenance personnel then began collecting the trash and hauling it to landfills in Coulee Dam, Davenport, and Kettle Falls in plastic bags. [33]

|

| Installation of privy at Tiffany campground, 1961. This was one of many privies that were constructed out of prefabricated panels by crews living and working on a Reclamation barge that traveled from one campground to another. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

LARO began annual park-wide hazardous waste surveys in 1987 in response to increased state and federal regulations and awareness of the human health hazards associated with toxic wastes. In cooperation with Reclamation, LARO maintenance personnel developed procedures for identifying and disposing of hazardous substances and containers, based on national guidelines. Hazardous wastes hauled away as part of LARO's ongoing safety program include unused pesticides, lead-based paints, and automotive shop oils and solvents. The 1997 Resource Management Plan acknowledged that LARO needed to identify hazardous materials used in the park, clean up hazardous waste sites, and train Park Service and concession employees on the issues. LARO staff is currently preparing a Hazardous Materials Management plan. [34]

Gasoline and chemicals are shipped by railroad, trucks, and ferries around and through the NRA. Park Service staff responds to accidental spills of hazardous and/or toxic substances from commercial or private sources throughout the Lake Roosevelt area. The park developed an Oil and Hazardous Substance Spill Plan in 1989. The park has spill containment supplies that are available at various sites. In the 1990s, park staff worked with the Lake Roosevelt Forum's emergency services committee to develop a regional spill response plan. [35]

LARO's underground storage tanks became an issue in the late 1980s because of new Environmental Protection Agency standards. The park began phasing out its gasoline operations in many areas of the park and instead provided vehicles, boats, and equipment with credit cards for use at service stations. The park prepared a Storage Tank Management Plan in 1991 for the nineteen regulated tanks used by park and concession staff and for the four unregulated tanks at Park Service headquarters. By 1993, LARO had only three underground storage tanks. [36]

Domestic Water Supply

The domestic water supply for LARO relies on wells and springs. Year-round wells have always been a challenge. The annual winter drawdowns make some wells and pumps unusable since the groundwater levels near the lake are within a few feet of lake level and fluctuate as the lake does. Through agreements with Reclamation and the Washington Department of Health, LARO installed a series of small water systems at its developed sites in the 1950s. Because they used seepage water from Lake Roosevelt, they did not function during the winter. Some wells eventually failed completely. [37]

|

| Laying water pipes at Fort Spokane, 1963. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

LARO maintenance worker Don Everts remembers that he and his co-workers "got a little fascinated with drilling for water" in the 1950s. At Fort Spokane, for example, U.S. Geological Survey geologist Fred Jones used a drill rig to dig a well that did not produce any water, and the Geological Survey was not willing to try again without reimbursement. Superintendent Hugh Peyton then turned the job over to Everts, who read all he could find on drilling wells. Everts decided to "blow" the well drilled by the Geological Survey using dry ice brought in from Spokane. They lined the well with rubber and dropped cakes of dry ice down the hole. They were standing on top when the water reached the top and literally blew them off — the water shot fifty feet into the air. After dropping more ice down the well and watching the water blow out a number of times, they pumped the water out of the hole and dropped a pump in it. They never pumped it dry after that. Water for several restrooms and all the campground water came out of that "dry well." [38]

By the late 1960s, twenty-two of LARO's thirty-five developed campgrounds and picnic areas had water supplies, some adequate and some inadequate. LARO continued to experience problems with wells that went dry during low reservoir levels. In 1969, LARO asked the U.S. Geological Survey to help investigate the availability of additional water supplies at all campgrounds and picnic areas. It was found that groundwater, preferred over surface water because it did not require treatment, could be obtained at most of LARO's campgrounds. The chemical quality of the groundwater was found to be good, although hard and in some places high in iron. [39]

Sampling of LARO's drinking water at campgrounds in the 1960s and 1970s found that some water supplies occasionally had high coliform levels. Treatment consisted of the installation of chlorinators and iodinators. Generally, the lower end of the lake maintained acceptable coliform levels. Two of LARO's sixteen water systems that used wells (Kettle Falls campground used city water) were closed in 1975, and the Park Service began sampling all water systems twice a month when they were in use. In 1976, new drinking water standards became effective with the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act. District rangers were required to sample drinking water systems on a regular basis. [40]

As regulations on drinking water tightened, the time spent by LARO personnel monitoring water supplies also increased. In 1979, LARO expended 283 person-hours, 7,206 vehicle miles, and 12 boat hours on water sampling and monitoring. Even so, in 1980 eight out of seventeen quality failures in the region occurred at LARO. Two wells were closed until disinfection equipment could be installed, and LARO planned improvements at several water supply systems to comply with national standards. As a result, six new wells, two pumping units, and fifteen iodinators and chlorinators were installed. By 1997, all twenty of LARO's wells had treatment systems, and they all had satisfactory microbiological quality. [41]

The largest spring within LARO is the historic spring at Fort Spokane, first used by the military and now by the Park Service. In 1994, the Park Service filed a formal protest with the Washington Department of Ecology against a planned large withdrawal of water for a nearby proposed recreational vehicle park because it was believed to threaten the spring. The permit is currently on hold until a state moratorium for new water rights on the Columbia River is lifted. [42]

Maintenance

In the 1940s, the primary maintenance tasks at LARO involved minor or routine work on Park Service equipment such as vehicles and boats and on the radio communications system; there were no government facilities to maintain. Reclamation employees in Reclamation shops did all major repair work on Park Service vehicles. Reclamation also frequently loaned heavy equipment to LARO personnel. The park's first two permanent maintenance positions were established in 1962. LARO's maintenance employees have traditionally been mostly seasonal workers who already lived in the area when they were hired. [43]

LARO began to acquire and develop more equipment, buildings, and recreational facilities in the 1950s. Many of the boats, vehicles, and pre-assembled buildings were military, Reclamation, or other federal agency surplus. By 1950, the NRA had five boats and a warehouse/workshop building in the North Marina area (the latter was locally referred to as the "hobby shop"). LARO put up a corrugated aluminum building at Kettle Falls in 1951 to store picnic tables, noxious weed eradication supplies, and other materials. Soon the Park Service owned several residences and garages, all of which were maintained by NRA maintenance crews. As recreational sites were developed, LARO added comfort stations, bathhouses, and visitor contact stations to its facilities. [44]

|

| Kettle Falls Ranger Station, no date. This building was one of the first to be constructed at LARO, and it is still in use as a contact station. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center (HFC 64-155). |

|

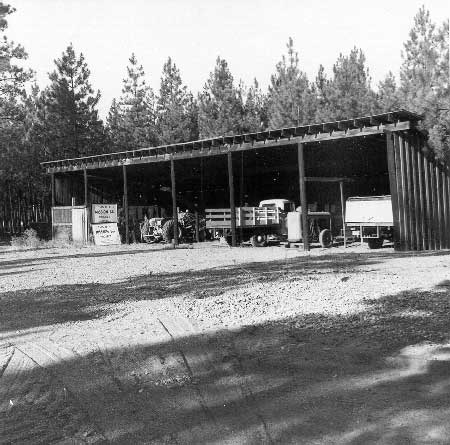

| Park Service equipment shed at Kettle Falls, 1960. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

LARO maintenance crews were responsible for a great variety of tasks, including road maintenance, equipment repair, facility maintenance, landscaping, grading beaches and placing log booms, maintaining communications systems, maintenance and extension of boat launch ramps, installing floating comfort stations, trail maintenance, building concrete fireplaces and other campsite amenities, maintaining utilities, plowing snow, and fencing. Most of the building maintenance was done between September and May rather than during the visitor season, and lakeshore facilities were often worked on during the annual winter/spring drawdowns. [45]

LARO employees went over the catalogues of General Services Administration surplus property published three or four times a month and put in requests for items they wanted, ranging from vehicles and boats to smaller items such as buoys and cables. Later Superintendents may not have been as enthusiastic about searching for used equipment, but Hugh Peyton and Homer Robinson saw the savings and rose to the challenge. All of LARO's early boats were surplus from government agencies. One, a thirty-six-foot Criscraft, was fast and expensive, popular with Regional Office staff and resented by local people. LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson obtained LARO's military-surplus fifty-six-foot flat-bottomed landing craft (named the Pelican but renamed the Heron by mistake during an overhaul) from a Navy yard in Seattle. This watercraft proved to be extremely useful for establishing boat-in areas and for cleaning floating debris because it could haul trucks and bulldozers and other heavy equipment to sites that lacked road access. [46]

|

| Pelican, LARO's military-surplus landing craft, being lowered into Lake Roosevelt, 1961. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

One of LARO's unusual acquisitions during the 1950s was heavy cast-iron practice bombs with fins on the back ends. Don Everts hauled two or three truckloads to LARO from a military air base, and NRA personnel painted the bombs white and installed them fins down as guard rails. Everts thought they were "a work of art" and unrecognizable to the average person, but someone from the Regional Office in San Francisco recognized the surplus practice bombs and ordered them replaced immediately with concrete posts. [47]

|

This place was built on surplus material.

-- Don Everts, LARO employee 1951-1982, 1999 [48] |

LARO personnel during the 1950s and 1960s generally exhibited a "can do" attitude that permeated every aspect of their jobs. The Superintendents gave the maintenance staff free rein to solve problems with ingenuity and creativity, recognizing that they had limited funds and equipment with which to work. As Don Everts commented about much of his work during this period, "Here we go again with our little old pickups and hammers." [49]

During the 1960s, more work and storage space was provided in the three districts for the maintenance division, gradually replacing the old war-surplus buildings in some locations. The older, temporary buildings needed much more maintenance than those that replaced them. [50]

|

| LARO personnel converting oil drums into garbage cans, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

The creation and maintenance of swim beaches is an ongoing job at the NRA. Two hundred tons of sand are lost each year due to wind, waves, and drawdowns. LARO maintains at least one sandpit as a source of replacement sand. The sand in the gigantic sand pile in Coulee Dam, behind park headquarters, is the size of pea gravel. Although it is not suitable for beaches, the Park Service and county and state highway departments use it for road work. [51]

Unlike many other Park Service units, at LARO the district rangers supervised routine or minor maintenance operations while the park engineer offered technical assistance and was responsible for major maintenance, engineering, and construction. Maintenance staffing expanded in 1965 to 4 permanent positions and 5.6 seasonal. They were responsible for over 450 campsites and some 240 picnic sites at 34 different locations, plus all the associated visitor and administrative facilities. One of the first women hired in a seasonal maintenance position at LARO was Ranae Colman, hired in 1972 and converted to full-time subject-to-furlough in the 1990s. [52]

In 1972, LARO's maintenance staff placed the maintenance of buildings, picnic tables, wooden signs, and garbage cans throughout the NRA on a scheduled program. Soon other maintenance tasks were added to the cyclic maintenance program, such as chipping and sealing roads, working on docks and floating facilities, bank stabilization, buoys, markers and anchors, painting building exteriors, residing buildings, roof replacement, and furniture replacement. In 1976, LARO added the historic buildings and foundations at Fort Spokane to the cyclic maintenance program. The funding was initially used for painting and foundation stabilization. Some of the park's permanent maintenance employees have received training in historic preservation techniques to better care for the historic military structures. The current cyclic maintenance program includes three types of projects: regular, natural resources, and exhibits. Parks submit their projects each year based on a ten-year program. LARO's base funding does not provide for adequate routine maintenance; having maintenance employees work longer seasons would help reduce the backlog. [53]

The 1980 State of the Parks report to Congress found that all Park Service units were in trouble. As a result, facility maintenance and repair received increased attention throughout the National Park System. The Park Restoration and Improvement Program of 1981-1985 was a high-profile program aimed at upgrading park facilities and infrastructure that had suffered years of neglect. For example, LARO used funds from this program for shoreline stabilization, surface coating of major gravel roads, replacement of swim floats and lifeguard stands, and rebuilding the boardwalk at Fort Spokane. [54]

Computers have allowed LARO's maintenance staff to track their time better on a wide variety of projects, rather than just special projects as had been previously done. The field people have become more involved in computerized recordkeeping. LARO used Maintenance Management System, a program established in the late 1980s to provide a Servicewide preventive maintenance program. It required detailed inventory information on physical assets and the work associated with maintaining each asset. LARO staff developed and computerized their own version and put it into use in 1989. This software was not Y2K compliant, however, so in 1999, reports South District Maintenance Supervisor Ray Dashiell, "we shot it." LARO is now one of about thirty parks participating in a pilot program to test new maintenance software called Maximo. [55]

|

| Clearing the beach at Kettle Falls, 1963. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

Former LARO Superintendent Gary Kuiper commented that in the 1980s LARO had a reputation for looking good, saying, "Our maintenance crew, to the person, was so sensitive to how they came across and how they made the place look." [56]

During the 1980s, LARO's maintenance workload increased greatly because of higher visitation, more developed areas to maintain, the noxious weed control program, maintaining the fee collection systems, increased marine maintenance, the hazard tree/thinning program, more work related to concessions, and additional agency paperwork. By 1990, many routine maintenance items such as tree pruning, working on signs, road maintenance, and weed control were no longer accomplished routinely or on schedule. This was mostly due to increased visitation and to the need to provide minimum services at each developed area. The LARO Facility Manager requested that, like other LARO divisions, maintenance subject-to-furlough positions be converted to full-time positions. About half a dozen maintenance positions were converted. This change spread the workload out more evenly over the year, since winter work could include tree thinning, inside work on facilities, equipment care and repair, dock repair, and repair and construction of tables, benches, and garbage cans. During the busy summer season, maintenance crews spend most of their time cleaning and caring for campground facilities. [57]

|

LARO's Assets, 1989 39 miles of roads8 miles of trails 50 housing units 151 public and administrative buildings 188 utility systems 1,870 acres of grounds (182 acres mowed, 43 acres irrigated) 435 miles of shoreline 257 docks/bulkheads/ramps 64 boats [probably includes canoes and rowboats] 35 park vehicles plus: campgrounds, picnic areas, swimming beaches [48] |

LARO's Facility Manager completed the park's Fleet Management Plan in 1990. It established policy for operating, maintaining, and acquiring all motor vehicles, equipment, and boats owned or leased by LARO. LARO had about sixteen boats and over thirty vehicles in 1992. The NRA made a major change in 1999 when it turned over its vehicles to the General Services Administration. The park now leases most of its vehicles under 26,000 pounds gross vehicle weight from this agency. The leased vehicles are replaced more frequently, which improves safety, but the additional cost — about 3 percent of LARO's budget — has had to be absorbed by the recreation area. This conversion from Department of Interior ownership to leasing was done in response to national directives to use leased vehicles wherever possible. [59]

The Recreation Fee Demonstration Program, established in 1996, allows parks to keep a percentage of the fees they collect. This program provides a reliable source of funding to LARO for minor construction, rehabilitation, and cyclic maintenance. Some of the projects funded by this program in the late 1990s include installing solar lighting for various visitor facilities; making restrooms accessible; extending launch ramps; constructing picnic shelters; installing curbing and sidewalks; and adding shore anchor and courtesy dock improvements. [60]

LARO began participating in the nationwide Youth Conservation Corps program in 1977. The first crew built a tent camp to house the teenage enrollees. The crews work with park maintenance crews on tasks such as putting up fences, painting, and picking up litter, and they are supervised by maintenance foremen. The number of enrollees over the years has ranged from about ten to twenty-four, and currently all crews are composed of local young people. The projects accomplished by these crews have varied widely, from building the Lava Bluff Trail to timber stand improvement, noxious weed control, installing gabions, building a boat launch ramp, and campground maintenance. In 1993, the Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI) funded a Native Youth Corps program at Fort Spokane district. This program has been discontinued, however, because it required so much time of supervisors. [61]

Landscaping LARO's developed areas has been recognized as a major maintenance item since the planning period of the early 1940s. Although Park Service policy encourages incorporating "sustainable design" into park work programs, the establishment of irrigated lawns and shade trees has always been seen as critical at the recreation area. Park staff did experiment with letting some areas go natural, but the resulting powdery dirt and dying trees proved unacceptable to visitors. [62]

|

| Spring Canyon Campground, 1956. Note the young trees planted to provide shade and shelter for campers in future years. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center (HFC, WASO-B-828). |

During the initial construction work on the major areas in the 1950s, topsoil was hauled in, lawns were seeded, and hundreds of shade trees were planted in picnic and campground areas. Sometimes this required almost heroic efforts. At North Marina, for example, LARO personnel used a surplus telephone-pole digger to dig holes. Then they filled the bottoms with powder and blasted them to break up the clay and rocks before filling with topsoil and planting trees. Other ongoing tasks have included applications of fertilizer, mowing, pruning, rodent control, and spraying to control insects. On occasion, attempts were made to eradicate native sagebrush from developed areas. Lawns, shrubs, and shade trees require much water for irrigation because the soil is sandy. LARO upgraded its water and irrigation systems in the early 1970s using regional reserve funds, including installing a large water-storage tank at Fort Spokane and replacing the "old hodge-podge watering system" [63] at Spring Canyon. The headquarters building was landscaped in 1972 using a plan prepared by the Regional Office. By 1989, about half of LARO's recreation sites had some maintained landscaping. Until the 1990s, most of the trees and shrubs were exotic species purchased from nurseries (native grasses were planted a little earlier, beginning in the 1980s). [64]

The Park Service directed all parks to reduce energy consumption in the early 1970s. At LARO, this initially affected vehicle use, causing reductions in off-site staff training. Maintenance staff developed energy conservation measures for LARO's buildings, including insulation, double-paned windows, and lower thermostat settings. The park also began separating and recycling selected materials and using biodegradable and/or recyclable materials as much as possible. Wood-burning stoves were installed in some employee dwellings. LARO appointed an Energy Coordinator in 1978, reflecting the program's high-priority status. In 1979, a concerted and successful effort was made to lower energy consumption by reducing lawn mowing, combining vehicle trips, reducing air conditioner use, and other means. LARO Superintendent William Dunmire, in a letter to all employees, commented, "Those Park Service bikes now in use at Kettle Falls don't use a drop of gas; more are on order for Fort Spokane." [65] High-mileage compact vehicles gradually replaced the NRA's "land whales." The interpretive program included energy-related programs such as a solar energy demonstration. Energy conservation and recycling projects continue to the present, although employees no longer save energy by riding bicycles while on duty. Currently, LARO has some solar lighting for vault toilets and bulletin boards. [66]

LARO began working on making its visitor facilities more accessible to people in wheelchairs as early as 1970 by installing ramps and widening comfort station stalls at major developed areas. The Spring Canyon bathhouse was the first facility designed for disabled visitors. The Park Service was required to do this by the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968. In 1978, a Regional Office employee surveyed wheelchair access at LARO, and plans for retrofitting facilities were adopted in the following year. Maintenance worker Don Everts remembers that it was difficult to retrofit some facilities according to Regional Office designs; "they could sit down there with their drawing boards and pencils and pictures and maps and come up with some beautiful stuff," but making the changes in the field was not always so easy. LARO's 1980 General Management Plan stated that all new facilities would be fully accessible and that existing facilities would be retrofitted wherever possible. The maintenance division completed an accessibility survey in 1988 and found several problem areas, such as the buildings at Fort Spokane, comfort stations and pit toilets, picnic areas, and swim beaches. Some of these facilities have been replaced or retrofitted since 1988. In 1992, the Park Service was required to use the more stringent ADA Accessibility Guidelines rather than the Uniform Federal Accessibility Standard that parks had been using in designing construction projects. Full accessibility of LARO's land and water facilities has not yet been achieved. [67]

Today, visitor satisfaction with LARO's facilities is high. One complaint that is frequently heard, however, concerns the lack of hot showers. The park's position, however, is that showers are provided by the private sector near Park Service facilities, and LARO does not want to compete with local businesses. [68]

Concessions, 1940s-1956

As the reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam filled in the early 1940s, the Park Service and other interested agencies debated the merits of public and private services for recreationists. By the fall of 1940, a commercial boating company was operating on Lake Roosevelt under a Reclamation permit, and by the spring of 1941, Reclamation had received many inquiries from people wanting to start commercial operations. The committee working on Problem No. 26 in 1940 felt that it needed a preliminary plan for managing the recreation on Lake Roosevelt to ensure a "rational coordination" of early private development and subsequent public development. Some of the Reclamation and Park Service caution in recreation planning was perhaps related to the experience of these agencies at Lake Mead in the 1930s. At that man-made reservoir, a private Nevada corporation had established ambitious tourist facilities near Boulder Dam in the late 1930s that took over small, independent concessions but was virtually ruined within just a few years. Frank Banks of Reclamation in Coulee Dam had heard that there was "some friction" between Reclamation and the Park Service at Boulder Dam. He expressed concern in 1941 that Reclamation had "no plan of operations [for recreational development of Lake Roosevelt], and 'hit and miss' development of recreation facilities is obviously undesirable." [69]

In the debate over which agency or agencies should administer recreation on Lake Roosevelt, the possibility of tribal members or the tribes establishing recreation enterprises within the Indian Zones was discussed by Problem No. 26 committee members as early as 1940. The CCT and the STI expressed their desire to earn revenue from the sale of leases, licenses, and permits for fishing, hunting, and boating; in fact, a 1943 Office of Indian Affairs memo proposed that tribal members should have the exclusive right to establish boat docking facilities on the waters adjacent to their lands. The 1945 Solicitor's Opinion resolved this issue for the time being by holding that Indians had the same rights and opportunity for private and commercial uses and public recreational development of the entire reservoir as anyone else, but they did not have the exclusive right to use the Indian Zones for commercial or public recreational purposes. F. A. Gross, Superintendent of the Colville Indian Agency, felt that forestry, stock raising, and mining — not recreation — would bring the greatest economic benefit to the Indians. He commented, "We believe that white owners of concessions on white owned or leased land along the reservoir shore will dominate the situation, largely to the exclusion of the Indians, who will continue to develop their more natural aptitude in logging and stock raising." [70]

LARO's Superintendent Claude Greider, on the other hand, believed that the Indians could benefit greatly from future recreational development of the lakeshore; he mentioned the townsite of Klaxta opposite Fort Spokane as a potential resort site. [71]

The Reclamation office initially handled all permits for private recreational developments on Lake Roosevelt. The Grand Coulee Navigation Company, founded by two men from Everett, Washington, was granted a permit in June 1940 to operate a passenger boat service on Lake Roosevelt. From then until the fall of 1944, the company operated a 65-foot passenger boat, the Miss Coulee, between its docks near Grand Coulee Dam, Narrows Bridge, and Kettle Falls bridge (this boat was then sold and moved to Lake Chelan). The company sold stocks in the Lake Roosevelt area and was under local control by 1942. C. E. Marr began a boat fuel and storage operation at Fort Spokane in 1941. He installed above-ground gas tanks that LARO landscape architect Phil Kearney called "most unsightly." Kearney also noted that, "Members of the Bureau staff have shown some dissatisfaction with the way our project has stalled along and I certainly cant [sic] blame them but the result is that they have been rather lenient with private interests and we can have little to say to that." [72] Finally, in the summer of 1942 the Park Service took over the responsibility of handling all inquiries concerning commercial uses of the reservoir, including potential and existing concessionaires. [73]

|

| Miss Coulee brings tourists close to the construction work at Grand Coulee Dam, 1940. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection. |

Interest in providing rental houseboats to the public was acknowledged in the Development Outline for Lake Roosevelt prepared in 1944, but houseboats were not recommended because of sanitation problems and the need to protect scenic values. Thirty years later, however, the concessionaire at Spring Canyon, Boyce Charters, offered one houseboat for rent. [74]

|

Our [Reclamation] office at the dam has had

many inquiries from people wanting to start something to make money.

There are three or four organizations that have made efforts to tie it

all up for themselves. We have managed to stave off attempts such as

this up to now but now people are building boats and going for rides on

the lake and everybody seems to be getting ready to utilize this

playground.

-- Phil Nalder, Reclamation, 1941 [76] |

The 1944 Development Outline for Lake Roosevelt spelled out some concession-related policies. It stated that all public facilities for which a user fee was charged would be under private operation, while the administrative agency would manage the free facilities. The Park Service did not want to provide overnight housing within its parks unless accommodations were not available adjacent to the NRA. At Lake Roosevelt, however, the policy was to avoid competition with private enterprise near Grand Coulee and Kettle Falls; there was also concern about private development failing to meet the government's high standards and a tendency for private enterprise to exploit the public. To allay some of these concerns, LARO's 1948 Master Plan stated that concessionaires' plans for buildings and grounds had to be approved by the Park Service. [75]

Meanwhile, applications for concession permits from investors continued to land on Greider's desk. In 1945, a western Washington investor proposed leasing 320 acres at old Fort Spokane to establish a lodge and club house, summer cottages, golf course, swimming pool, tennis courts, landing strip, and complete service for pleasure boats. The investor had been talking with Frank Banks about his plans since about 1938. This deal never happened. Instead, in these early years the Park Service proceeded cautiously, granting temporary permits to companies that offered to provide the services that LARO considered most essential and turning down or postponing decisions on many others, such as proposals by inexperienced returning veterans and proposals for "low-grade resorts." The temporary permits issued between 1940 and 1945 did not confer any prior rights to long-term concessions once the administrative authority for the area was established. [77]

LARO, unlike many other Park Service units, has never had just one concessionaire operating as a regulated monopoly. By 1945, three operators were providing boating services on Lake Roosevelt. The Grand Coulee Navigation Company had two boats that carried 25 and 125 passengers on both scheduled and charter trips. Most of that company's income came from bus tourists and the charter and cruise business. The two other operators offered short speedboat trips to visitors at the dam. One of these, the Coulee Dam Amphibious Aircraft Company, received its initial permit in 1944 for operating a fueling service for boats and seaplanes near the dam. Soon they were also offering flying instructions, sightseeing boat and airplane rides, and boats and planes for hire. [78]

The Tri-Party Agreement of 1946 designated the Park Service as the official administrative agency for recreation on Lake Roosevelt and thus the agency that issued permits for concessions within the NRA, including within the Indian Zones. The Park Service took over this function on July 1, 1947. The revenues from fees charged the commercial operations reverted to the Reclamation Fund, Grand Coulee Dam Project and, in turn, Reclamation helped fund LARO's administration and planning. From the beginning, LARO personnel planned on full development of the NRA as coming from a combination of federal and private funds. LARO's major challenge in its early development program was to obtain the funds to provide the roads, utilities, parking areas, picnic areas, swim beaches, and landscaping necessary at the major development sites to attract private concessionaires to invest. [79]

As of August 1947, LARO had five special use permits with individuals or companies providing recreational services, as follows:

- Walter McAviney, Gifford-Inchelium ferry, with heavy summer recreational traffic,

- Coulee Dam Amphibious Aircraft at Coulee Dam, providing public boat rides, float plane rides, boat dock facilities, hangar, mechanical service to boats and planes, flying instructions, and refreshments,

- Grand Coulee Navigation Company at Fort Spokane, round-trip daily boats between Fort Spokane and Grand Coulee Dam, not prospering,

- Stranger Creek Grange at Gifford (discontinued in fall 1947), picnicking, bathing, dancing, and boating facilities available to the public, primarily locals, and

- W. J. Bisson at Kettle Falls, boat fueling facilities at Kettle Falls in conjunction with camping development on operator's adjoining private land. [80]

The lack of Congressional appropriations to LARO for construction projects continued to hamper the efforts of Park Service personnel to attract private investment to Lake Roosevelt. For example, in 1948 Congress allocated only $15,000 of the $1.7 million that LARO had requested for developing the three major areas on the lake. The Park Service continued to turn away some interested private parties, but this was also a period when many expired Park Service concessions around the nation attracted no bidders, despite the booming tourist industry. [81]

Small problems with the Grand Coulee Navigation Company (GCNC) surfaced almost immediately, hinting of larger problems to come. For example, in 1944 Greider informed the president that his company had not complied with the conditions of his special use permit or with a letter asking him to remove a small building on the bank of Lake Roosevelt. By 1947, Greider had decided not to renew the annual permit issued to GCNC because it was still disregarding major requirements of its permit with the Park Service. [82]

Greider either reconsidered his opinion of the GCNC or was overruled. By May 1948, after "lengthy consideration," he recommended that the company be granted a concession permit for the Fort Spokane area. The company planned to build a dock immediately, followed by various visitor facilities once the Park Service had constructed the water and sewer system. The company was formed of well-to-do and politically well-connected businessmen and farmers of Davenport who were reportedly prepared to spend $200,000 or more during the first six years of operation. Previously, concessionaires' fees at LARO had been flat fees. Greider recommended (and it was eventually so decided) that the GCNC fee be based on net earnings of the company above 6 percent net profit. Reclamation and the Park Service drew up a five-year concession permit for GCNC in August 1948, but because the Secretary of the Interior withheld his approval, LARO ended up extending the existing GCNC special use permit for one year. GCNC, however, did not sign the temporary permit because it lacked support for their intended investments. [83]

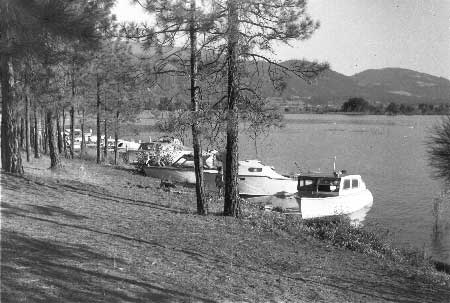

|

| Boats moored to trees and bushes at Kettle Falls, 1956. This was a common sight in the early years because of the lack of public docks. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center. |

By 1947, the Coulee Dam Amphibious Aircraft Company (CDAA) had a plane hangar, a boat dock (used by the Park Service for their boats for a fee), and a fueling station for planes and boats near the dam. The company was financed by Standard Oil Company, and as of summer 1948, it had invested some $70,000 in its facilities. Because of CDAA's heavy investment, the Park Service intended to replace their special use permit with a concession permit. The company suffered a heavy blow, however, in the summer of 1948 when Arthur Loepp, president and principal stockholder, was killed in an airplane accident. In May 1949, in a move that Greider believed would solve the concessionaire problems at Coulee Dam and Fort Spokane, GCNC purchased and took control of the Coulee Dam Amphibious Aircraft Company. The CDAA was dissolved in May 1950, its permit was cancelled, and a twenty-year GCNC concession contract was approved January 1950. The contract gave GCNC preferred but not exclusive rights in all of LARO and was amended to cover the CDAA's airplane business. In 1950, the Park Service began to build roads and establish utilities at Kettle Falls and Fort Spokane, and GCNC provided boat dock and fueling facilities at both these sites in addition to its boat and seaplane base at Coulee Dam. [84]

At a 1950 meeting with manager Cliff Hutsell of GCNC, the Park Service agreed to include construction of utilities at Fort Spokane and Kettle Falls in the fiscal year 1952 program. The plans, approved by the Park Service, called for tourist cabins at both locations, although the layouts prepared for Fort Spokane were dependent on Park Service acquisition of the Fort Spokane Military Reservation lands. Park Service personnel pointed out to Hutsell that Park Service funds were always dependent on Congress and so could not be guaranteed. Most of GCNC's income after World War II until 1951 came from flight instruction, which was largely government-financed under the GI Bill. The company added new services to its list in 1950: boat and motor rental, buoy moorage, and boathouse service/work space. [85]

GCNC's finances were always precarious. In 1951, even with boat launch ramps, fueling stations, and docks at Kettle Falls and Fort Spokane, the company was not earning enough money to pay its attendants' wages. When LARO determined that it would not be able to provide the needed facilities at these locations in 1951, GCNC requested permission to move in temporary buildings to house an office, lunchroom, and store at each location. The Park Service approved this plan with some hesitation, including the relocation of a store previously located at Miles. Hutsell agreed to build a general store and six cabins at Kettle Falls. But he also began a letter-writing campaign to his Congressional representatives complaining about the slow pace of development at Lake Roosevelt and urging that LARO development of access roads, sanitary facilities, and drinking water be concentrated at one site rather than spread thinly around the reservoir. The Park Service agreed with this latter point and even tried to transfer funds from a power-line project and from the Lake Roosevelt debris-cleanup project to constructing a ranger station, dredging the harbor, and sign construction at Kettle Falls in order to support GCNC's plans to build facilities there in 1952. [86]

The GCNC antagonized LARO personnel and others in 1952 when it bought a tugboat and began towing logs and barging lumber for Roosevelt Lake Log Owners Association. Lafferty Transportation Company complained about the competition, but Greider defended GCNC's right to pursue this avenue of earning revenue, stating that Lafferty had been doing the job carelessly. Within a few months, however, the log owners' association terminated its agreement with GCNC because of unsatisfactory work performance. Hutsell filed complaints with the Park Service about various aspects of the new contractor's work, but Greider was disinclined to pay much attention. By this time, he recognized that unless the GCNC could get proper financing, "it may constitute quite an administrative problem." Greider continued, "I am doing what I feel proper to keep Mr. Hutsell's spirits and activities in proper line." [87]

In 1952, GCNC agreed to build a coffee shop, boat repair shop, and seven cabins at Kettle Falls but was unable to complete the work because of lack of funds. LARO, although restricted by limited funding, did construct utilities and roads at Kettle Falls that year. LARO also constructed a road, parking area, and launch ramp at Fort Spokane, but GCNC did not have the funds to do the promised work there either. Meanwhile, the Park Service was being criticized for its concession policy at LARO, and the Regional Office began asking the company to furnish evidence of its intention and ability to fulfill its commitments. That summer, the Park Service disapproved GCNC's proposal to buy the Miles store, which Hutsell saw as a "killing blow" to his efforts to restore public confidence. Hutsell blamed his stockholders' discouragement on the negative public response to the proposed regulations for LARO combined with the uncooperative attitude and development restrictions imposed by the Park Service and Reclamation. He did acknowledge that World War II and the Korean War played a role in disrupting the plans of his company and of the Park Service. [88] The following is an example of the tone of Hutsell's many letters to Park Service officials:

Our recurrent suspicion that the local administration of the National Park Service is inimical to the interests of this company has developed into a conviction. It does not seem possible that unbiased stupidity could have resulted in an administration so consistently adverse to the interests of this company and to, what we believe is, the purpose of the National Park Service in this area. . . . The result is public antipathy to the National Park Service administration of the area and unnecessary operating losses to this company. [89]

Relations between Greider and Hutsell rapidly deteriorated until in January 1953 Hutsell told the Park Service Regional Director that he did not wish to meet or deal with Greider at all. The company continued to lose money, as it had every year since 1940. Hutsell's criticism and blame for the company's poor showing and inability to obtain funding covered a variety of topics, such as bad public relations, poor boating conditions due to driftwood on the lake, Park Service non-cooperation with GCNC, lack of signs directing visitors to facilities, Reclamation competition with public docks at North Marina, and inefficient use of appropriated funds (he was particularly incensed at the construction of employee housing). In a statement aimed directly at Greider, he cited the "tactless and belligerent" handling of the negotiations of the regulations for the NRA as leading to widespread bad publicity. Greider, in turn, began urging the Regional Office to cancel GCNC's concession privileges at Kettle Falls and Fort Spokane. [90]

After much deliberation on both sides, in April 1953 GCNC decided to relinquish its claims to the Kettle Falls area. Two months later, Claude Greider was transferred from LARO to the Park Service's Portland office. In 1956, the concession contract with the GCNC was terminated and LARO released a prospectus asking for proposals for a new concessionaire. [91]

Concessions at LARO, 1957-1986

National Park Service concessionaires at LARO and other parks face a number of challenges, including seasonal operation; the need to have Park Service approval of all facility plans, designs, and materials; and Park Service regulation of rates, prices, and sale items. But the advantages include protection from competition and a guaranteed flow of customers. In 1958, the Park Service extended the maximum term of concession contracts from twenty to thirty years to provide additional advantages to concessionaires. The Concession Policy Act of 1965 reaffirmed the established concession-related policies of the Park Service. It required the Park Service to limit concessions to those necessary and appropriate to the parks' purposes, and it tried to ensure a reasonable opportunity for concessionaires to make a profit. The concessionaire may gain a "possessory interest" (all but legal title) to physical improvements, plus it has preferential rights for renewal, if operations are satisfactory. Legislation in 1970 confirmed that all Park Service areas, including NRAs, come under Park Service concession statutes. [92]

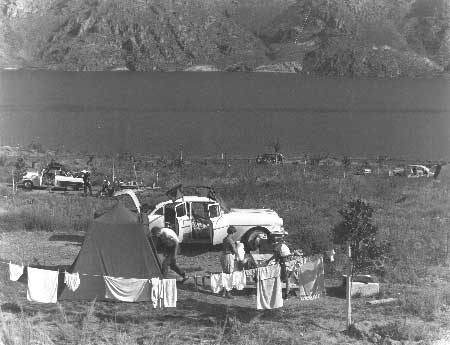

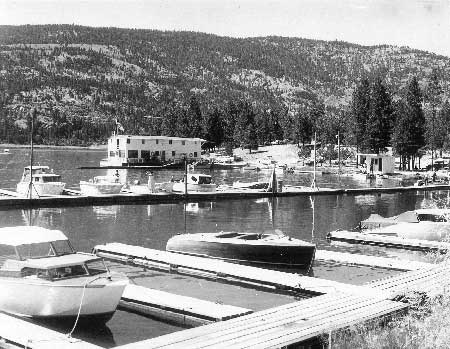

|

| Kettle Falls Marina, 1958. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

From the termination of the GCNC contract in 1956 until the 1980s, LARO concessionaires were small mom-and-pop operations, typically run by individuals or couples who offered visitors seasonal snack shops and perhaps docks and marina services. Most had such a low volume of business that LARO had difficulty finding people to operate them. Some years, the services were minimal at best. In 1957, for example, the only concession operation at LARO was a small food stand at Spring Canyon. In some of the major development sites in the late 1950s, boaters on Lake Roosevelt were advised to contact LARO rangers to obtain fuel for their boats. LARO's Mission 66 program called for concessionaires at Kettle Falls, Fort Spokane, North Marina, and Spring Canyon. The facilities desired included cabins and lodges, trailer sites, stores, eating facilities, gas stations, and docks. By 1963, however, LARO had decided that concessionaire accommodations were not necessary at LARO because private developments in nearby communities were adequate. [93]

|

| Concessionaires Mr. and Mrs. William Brauner and LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson at the Kettle Falls boathouse, 1958. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

In 1966, at the end of the Mission 66 program, LARO's visitor and administrative facilities reflected the lack of concessionaire investment in the NRA. Park Service facilities were valued at close to $760,000, while concession facilities were worth just over $4,000. [94]

Throughout the 1970s, LARO's concession operations continued to be marginal for most permittees. For example, only two of the eight concession permittees grossed over $5,000 in 1974. A permit for the rental of houseboats was issued for the first time for the 1973 season, but the concessionaire was hurt by the gas shortage. Another new idea was that of having students operate the Spring Canyon concession for school credit, which was put into effect in 1976 but was cancelled at the end of the year due to a substantial financial loss. LARO also implemented the Park Service's new Servicewide Concession Evaluation system in 1976. LARO staff worked on establishing a marina concession at Seven Bays, and this opened in 1978 with thirty boat slips and a small store (this concession, originally operated by developer Win Self, is now managed by the CCT). [95]

|

| Concession stand at Spring Canyon, 1968. This sandwich-and-pop stand was typical of LARO's concessions during the 1960s and 1970s. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). |

By 1978, LARO's two potential full-spectrum concession operations were located at Seven Bays and at Keller Ferry. A concession was needed at Kettle Falls, but previous efforts had proven to be economically unfeasible. Visitors surveyed that year opposed having restaurants and lodging facilities within the NRA, but they complained about the lack of showers and thought water ski areas, moorage, marine repair and supply services, boat trailer parking, hookups, and boat rentals might be desirable. Park staff identified additional boat moorage as LARO's greatest need, followed by boat maintenance services. The four concessionaires operating in 1978, all on five-year revocable concession permits, were as follows: 1) snack bar and boat fueling service at Spring Canyon, 2) marina with moorage for fifty boats at Keller Ferry, 3) thirty-boat marina at Seven Bays, and 4) camper supply and boat fueling service at Kettle Falls. LARO Superintendent William Dunmire noted that the Park Service would likely authorize the expansion of the two existing marinas, although it had been taking a "go-slow posture" in authorizing requests for additional concession services. [96]

|

Concessions at LARO, 1963

Kettle Falls — rental boats, mooring and storage services, sale of gas and oil, boat charter, sale of meals, groceries, drinks, ice, candy, souvenirs, camping supplies, laundromat, rental space for meetings (concession contract) Evans Campground — refreshment stand (concession permit) Pitney Point — boat mooring, oil and gas for boats, marine supplies (concession permit) Fort Spokane — boat fuel, oil, and marine supplies (concession permit) North Marina and Spring Canyon — rental lockers, boat fuel and services, refreshments, mobile vending truck selling ice (concession permit) -- "Master Plan," 1963 [98] |

By 1981, the value of the concession facilities at LARO had jumped to $230,000, about 8 percent of the value of Park Service visitor facilities. All LARO concessions (Spring Canyon, Keller Ferry, Seven Bays, and Kettle Falls) took in about $80,000 in gross receipts in that year. Some of the concessionaires were severely impacted by the unanticipated low lake levels in 1984 and 1985 during the visitor season. Congress established a Visitor Facility Fund in 1982 that used the franchise and building use fees charged concessionaires to fund maintenance and rehabilitation of government-owned, concessionaire-operated visitor facilities. As visitation to Lake Roosevelt increased in the 1980s, various landowners and corporations made proposals to LARO for concession operations, and LARO staff began to feel the need for a lake-wide comprehensive concession management plan. [97]

The CCT actively investigated a partnership proposal with the Del E. Webb Corporation, which had facilities at Lake Powell, for developing a marina-resort at Seven Bays, but in 1986 that company decided against the joint venture. [99]

Tribal Regulation of Concessions within the

Indian Zones, to 1975

The question of tribal rights to regulate and administer concessions located in LARO's Indian Zones was raised as early as 1958. As a result, LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson asked the Solicitor's Office for an opinion on the authority of the Park Service to regulate and administer concessions in the recreation area's Indian Zones. The 1958 opinion held that Indians had the same rights and opportunities for private and commercial uses and public recreational development of the entire reservoir as any other member of the general public but did not have the exclusive right to use the Indian Zones for such purposes. The Solicitor noted that in 1946 representatives of the Park Service, Office of Indian Affairs, and Reclamation favored having a central administrative agency control all commercial uses of the reservoir, including within the Indian Zones. So, the Park Service was granted the responsibility for approving and supervising the operation of any concession within the NRA, and the tribes were given no preference in obtaining concession contracts within the Indian Zones. [100]