|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Lewis and Clark Trail A Proposal for Development |

|

THE EXPEDITION

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

The Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806 is considered by many historians as the single most important event in the development of the western United States. Politically it secured the recent American purchase of the Louisiana Territory and extended American claims to the Pacific. Economically it provided the first knowledge of the resources which eventually led to the opening of the western lands for development and settlement.

In 1804 the United States was a young Nation of 17 States. Although having won independence from Great Britain, it was still dependent on rivalry among the three great powers—Great Britain, France, and Spain—for its survival.

Of the three, Spain was the weakest. In 1762 as its booty for helping Great Britain win the French and Indian War, Spain had been ceded the interior of the Continent west of the Mississippi River along with the key French city of New Orleans. The new lands merely added to Spain's already vast American holdings. So even after control of most lands east of the river passed to the United States in 1783, Spain continued to exploit her more immediately lucrative holdings in Mexico, Peru, and the Caribbean. She appears to have failed completely to grasp the significance of the fertile and temperate Mississippi Valley in the balance of world power.

Conquered by Napoleon early in the 19th Century, Spain made peace by returning all of the Louisiana Territory to France.

President Thomas Jefferson was at once alarmed. He knew the global political and economic significance of the rich Mississippi Valley, and he suspected that Napoleon did too. Dealing with a deteriorating and incompetent Spanish colonial administration had given the American Government no real worries. The ferment of revolutions for independence was stirring across all of Spanish America. When the revolutions came and the Spanish empire collapsed, Louisiana could be expected to fall easily into American hands. There was no occasion to join the push until Spain was actually at the brink.

Napoleon was a different matter. The most brilliant and effective of European military and political leaders in a millennium, he had conquered virtually the entire continent and possessed both the military might and the organizational genius to take real control of his possessions.

Jefferson correctly saw French control of New Orleans as an iron gate across the main artery of internal American commerce. Despite his own feelings about the limited powers of the national government, he boldly sent representatives to Paris to buy New Orleans.

They found Napoleon facing another war with Great Britain and embroiled in a hapless adventure in the Caribbean. Moreover, he was in debt and in need of money. If the French leader knew the global value of the western half of the Mississippi Valley, he was also realist enough to know that the Americans would take it sooner or later, for without a navy he could not hold it by force of arms against them. Should he sell New Orleans, he would have no way to exploit the rest of the continent. So, Napoleon gracefully startled the American negotiators by offering to sell all of the Louisiana Territory for $15 million.

Jefferson seized his opportunity and consummated the bargain, brushing aside any questions about the French title to the land.

On October 25, 1803, the United States Senate ratified the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. The following May 14, with the firing of cannon shot, the Lewis and Clark Expedition set forth from their winter camp at the mouth of Wood River, Illinois, to nail down the American claim to Louisiana and to extend American claims to the Pacific. Jefferson saw the 13 colonies for whom he had written a Declaration of Independence only 28 years earlier as a continental power which could some day be first in the world if her leaders were bold enough to act decisively when opportunity knocked.

The timing of the Treaty and the Expedition was fortuitous. Jefferson actually had planned the Expedition long before Napoleon made his offer and had proposed the appropriation of $2,500 for the journey in his address to Congress on January 18, 1803. Indeed, Congress had appropriated the money before it adjourned that March.

The need for such an expedition was clear. A route across the continent to the Oregon country was needed. Relations with Great Britain were strained and British fur traders were entrenched along the Missouri River. War with Great Britain could bring hordes of Indians attacking the frontier settlements. It was important that the United States Government know as much about the area as possible.

Few similar excursions were so well managed and so free from errors in judgment, miscalculations and tragedy. The trip lasted two years, four months and nine days. The Expedition traveled about 7,500 miles through a wilderness inhabited by warlike, hostile Indians and wild animals. Yet, there was only one dangerous incident with the Sioux Indians at the mouth of the Bad River and another with the Blackfeet which resulted in the death of two Indians. Only one member of the expedition died enroute, the probable cause a ruptured appendix. The Expedition was boldly conceived, well-planned and led by men whose abilities enabled it to attain its objectives.

The Expedition contributed substantially to shaping the political future of the North American continent. The contacts made by Captains Lewis and Clark with the various Indian tribes were of material assistance in the Government's later dealings with the Indians. By making a land traverse to the headwaters of the Columbia and then down that river to the Pacific Ocean, before the British were able to do so, the Expedition also provided a buttress to the American claim on the Oregon country.

In addition, economic benefits resulted from this Expedition across the Louisiana area. Contact with the Indians permitted trappers to penetrate into the area, followed by traders who purchased furs from these Indians. Lewis and Clark established that the western region contained a treasure of beaver, and exploitation began almost immediately. The fur trade, which was to be the principal industry of this region for many years, steadily increased in importance until late in the 1830's when prices for beaver pelts declined.

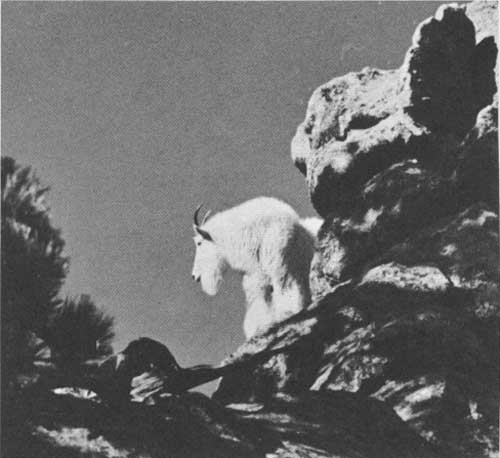

The scientific results added a great deal of information to the knowledge existing at that time. Descriptions of flora and fauna were made by Captain Lewis and other members of the Expedition and, when possible, specimens were taken. A number of birds and a prairie dog along with boxes of hides and Indian articles were returned to civilization. Detailed descriptions were prepared of the pronghorned antelope, the Columbia blacktailed deer, the mountain beaver, bobcat and numerous foxes, wolves, and squirrels. Also, for the first time, there was a reliable inventory of Indian tribes of the Northwest, with valued observations on their customs.

Geographically, the Expedition had more far reaching effects. At the outset it was generally assumed that by going up the Missouri River to its source, a short portage of possibly 20 miles would bring them to the headwaters of the Columbia River, which would run to the sea. The existence of an extensive mountain range such as the Rocky Mountains was not anticipated. As it turned out, they missed the headwaters of the Clark's Fork which would have given them easy passage to the Columbia and instead traversed some 200 miles of extremely rugged mountains to reach a tributary of the Snake. The Expedition provided much new material for the making of maps and dispelled once and for all the long-cherished idea of a northwest water passage to the Orient.

|

|

"These hills exhibit a most extraordinary and romantic appearance as the water has worn the soft sandstone into a thousand grotesque figures which seem the productions of art, so regular is the workmanship. . . Lewis and Clark Journals

1805 |

PHYSICAL SETTING

On their journey from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Pacific Coast and back, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traversed nearly 7,500 miles of western America and found a wide diversity of land formations, vegetation, and climate. From the hardwood forests of the Northern Ozarks to the rolling grasslands and cottonwood river bottoms of Kansas, Nebraska, and Iowa, they followed the muddy Missouri River north into what is now the Dakotas. Great herds of bison and antelope were seen along the rolling grasslands and other game was plentiful.

The explorers passed through the beautiful but desolate region of eastern Montana and on into the foothills of the Rockies. Here they encountered the fast, crystal-clear tributaries of the upper Missouri where steep canyons and pine covered slopes dominated the scene. Their arduous route continued through snow covered mountain passes, over the Continental Divide, and down the tributaries of the mighty Columbia to the Pacific. The cold, damp winter of 1805-1806 on the densely forested Pacific Coast provided an uncomfortable and dreary letdown after the heroic journey across half a continent.

Before starting on its journey, the Expedition spent the winter camped at the mouth of the Wood River near East St. Louis, Illinois just opposite the mouth of the Missouri River. The eastern portion of their route up the Missouri traversed what is now the heartland of America's "Grain Belt." This is still a region of flat, undulating terrain, but the boundless expanse of prairie grasses has been cultivated into carefully manicured fields layed out in squares like a huge checkerboard.

What was once the wide, wild Missouri has now been harnessed, channeled and diked. Cities and towns now line its banks and some of the brown sediment that gave the "big muddy" its uncomplimentary nickname has been settled out behind the upstream dams. Yet much of the charm remains. Cottonwoods line its banks, catfish lurk in the old oxbows and geese, ducks and other waterfowl still follow its course in their seasonal migration between feeding and nesting grounds. Today, the placid, predictable river offers abundant opportunities for boating and fishing. With more provisions for access and better regulations against water pollution, the Missouri could become the "playground of the prairie."

The most important changes in the Missouri River during the past 160 years, however, have been brought about by the construction of six huge reservoirs along its main stem. As a result, many of the historic sites and physical features of the Expedition's route now lie under the waters of these "Great Lakes of the Missouri." Although banes to history buffs, these reservoirs have become a boon to the water recreationists. Sailboats, motorboats, water skiers, and swimmers now enjoy the deep, clear waters which have replaced the shallow, twisting channels traversed by the cumbersome riverboats of Lewis and Clark.

Beyond the Mandan Villages these first voyagers were required to use smaller and lighter craft because of the increasing shallowness of the river. Passing the mouth of the Yellowstone River they found the surrounding terrain much more rugged. Above what is now Fort Peck Reservoir they entered the Missouri "Breaks," a desolate yet spectacular region where fantastically shaped rock formations towered above the river on both sides. It was from the summit of one of these pinnacles that Lewis got his first glimpse of the lofty crags of the Rocky Mountains—that rugged spine of America around, through or over which the Expedition would have to work its way to find the rivers that flowed down to the Pacific.

This region remains today much as it was in the spring of 1805. In fact, the 180-mile stretch of the Upper Missouri between the upper reaches of Fort Peck Reservoir and Fort Benton is the only major section of the Expedition's water route where present-day adventurers can relive the wilderness experience of the first explorers and can still marvel at the same scenic spectacles which inspired both Lewis and Clark to pages of imaginative prose. Now, too, game and other wildlife are only slightly less numerous than the abundance found by the Expedition.

As the Expedition moved forward, the river itself became narrow and crooked and the current more rapid. Upon reaching the Great Falls of the Missouri, the party was forced to perform a difficult portage which took four arduous weeks to accomplish. From the Great Falls to Three Forks, the route entered the Rocky Mountains where in many places granite walls rose perpendicularly to great heights. At Three Forks where the Gallatin, the Madison, and the Jefferson Rivers join to form the Missouri, the captains chose the southwest fork (the Jefferson) and proceeded to the mouth of the Beaverhead River. Ascending the Beaverhead to its headwaters, the brave band finally reached the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass and descended into the Salmon River Valley. Here they met the main body of the Shoshones and obtained horses for the rest of their trip over the mountains.

After the Expedition crossed to the Pacific side of the Divide they followed the scenic Salmon River for a short distance, until impassable terrain forced them to turn back. Friendly Indians then guided the explorers north over Lost Trail Pass and into the beautiful Bitterroot Valley. From there they traveled over the imposing Bitterroot Mountains via Lolo Pass and Lolo Trail until they found the descending waters of the Clearwater River. The extreme roughness of the terrain and lack of game made this by far the most difficult part of the journey. This region consisted of steep valleys, coniferous forests, lakes, and rapid flowing streams.

Upon reaching the Clearwater River, the Expedition constructed dugout canoes in which they floated down the river to where it joins the Snake at present-day Lewiston, Idaho. The Snake River was full of rapids and shoals which added to the scenic beauty but proved dangerous for the party. Today, this section of the Snake River is being tamed by dams which provide different types of water experience. But the deep canyons through which the river flows have limited road access and kept this section remote and isolated.

After the Columbia River was reached progress was more rapid for the next 200 miles to the now famous Columbia River Gorge which bisects the Cascade Range. Major portages were necessary in this stretch before reaching the tidewater which extends 140 miles upstream to the cascades from which the Cascade Range takes its name. The men found the going much easier from here through the Oregon Coast Range to the Pacific.

Like much of the Missouri and the Snake, this section of the powerful Columbia River has been harnessed into a series of lakes. Unlike the Snake, though, these impounded waters are paralleled by good roads and are readily accessible to the people living in and near the Columbia Valley.

In Montana, on the return trip, Lewis and Clark separated to explore the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers in more detail. With minor exceptions most of the land along these rivers today is in private ownership. The Marias has been changed somewhat by the construction of the Tiber Dam and Reservoir but it is generally remote from major highways. Several of Montana's larger cities are located along the Yellowstone. The construction of dams has altered the appearance of the Yellowstone very little.

In addition to these two major side trips the Expedition made several others. Generally, however, they followed the same route on their return to St. Louis in 1806.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

lecl/proposal-for-development/expedition.htm

Last Updated: 11-Jun-2012