|

Lincoln Boyhood

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER IV:

Euro-American/American Indian Relations

The tenor of relations between American Indians and Euro-Americans in the Northwest Territory was shaped by a variety of factors, including the formation of trade networks, the development of a patriarchal relationship between the French (and later the British) and the various Indiana tribes, and struggles for military and political control of the region. Epidemics and displacement of eastern tribes greatly affected the Indians' ability to respond to the changes in their traditional lifeways that intercourse with Europeans demanded. The succession of French and British traders by American settlers proved even more disruptive to traditional ways. Ultimately, American hegemony forced the Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, and other tribes to surrender all of their claims north of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi rivers.

PROTOHISTORIC AND CONTACT PERIOD ABORIGINAL OCCUPATION (ca. 1600 to 1750)

The identities of the tribes occupying Indiana in the early 1600s have not been established with certainty. Considerable displacement and migration was taking place among Indian tribes at this time, largely as a result of European colonization of the eastern seaboard. Furthermore, during the early-seventeenth century, the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) in northern New York carried on a lucrative trade with the Dutch and the English, exchanging beaver pelts for manufactured goods. By the 1640s, overtrapping had severely depleted the beaver population in Iroquois territory. Beginning in 1641, the Iroquois mounted a series of expeditions to the Western Great Lakes region seeking to gain control of the fur trade that the Huron and other western tribes conducted with the French. The Iroquois were equipped with firearms procured from traders in New York, which gave them a tactical advantage over their rivals and enabled them to drive the Huron from their traditional territory. Tribal warfare continued throughout the late-seventeenth century, with the Iroquois sporadically dispatching military expeditions into New England, south to Chesapeake Bay and the southern Appalachians, north beyond the headwaters of the Ottawa, and westward into Illinois. As a result, a number of western indigenous groups were displaced further to the east, west, and south. [54]

Around 1680, western tribes armed and supported by their French allies began a counter-offensive that ultimately succeeded in arresting the Iroquois ascendancy. In 1701, the representatives of the Iroquois League, the French, the British, and more than twenty western, eastern, and northern indigenous groups met in councils at Onondaga, Albany, and Montreal. A final council the same year in Montreal resulted in a comprehensive peace, ending the Iroquois Wars. [55]

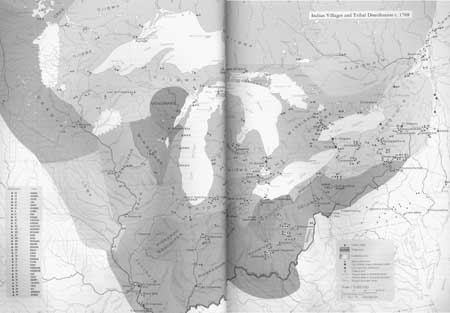

Large scale population shifts among Indian tribes were ongoing during this period and continued for more than a century. The Miami, Wea, and Piankeshaw are known to have arrived in northern and central Indiana after 1680. The Miami occupation may have preceded this date, as historical links between this tribe and Upper Mississippian cultures in Indiana and Illinois have been speculated, but not yet proven. The Kickapoo established villages in the Wabash Valley during the 1740s. By the 1780s, Delaware tribes migrated to Indiana from Ohio, and some groups of Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Wyandotte came shortly thereafter; the Shawnee also have been linked to the Fort Ancient culture of the 1600s in Ohio. [56] These groups were the first tribes encountered by European explorers during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5: Indian Villages and Tribal Distribution in the Northwest Territory, c. 1768 (Tanner, 1987: 58-59) |

EURO-AMERICAN OCCUPATION (1675 TO

1785)

The first forays by European explorers into Indiana occurred on a sporadic basis from the late-seventeenth through the mid-eighteenth centuries. Father Jacques Marquette may have crossed the dune country of northern Indiana in 1675. His successor, Father Allouez, probably crossed the St. Joseph Valley. Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle ascended the St. Joseph River in 1679, to the site of modern South Bend, Indiana. In 1681, and for several years thereafter, La Salle conducted extensive explorations throughout the region that became Indiana. By 1720, dozens of fur trading French voyageurs or coureurs de bois were engaged in trade with the Miami villages clustered along the Wabash River and its tributaries. In order to maintain open communication between Lake Erie and the Mississippi River, the French constructed forts along the Wabash-Maumee line across Indiana, at Miami, Ouiatenon, and Vincennes. These were the first permanent European settlements in Indiana and were constructed between 1715 and 1731. [57]

Locating forts and trading posts in close proximity to rivers represented a sensible and opportunistic choice on the part of the French. Rivers were central to eighteenth century life in Indiana. In addition to serving as the principal means of transportation, they were sources for water and fish, and the rich bottomlands proved to be fertile farmland. But while the French preferred to travel to their various posts by water, the Miami predilection was to travel overland. Numerous trails crisscrossed the region, serving as arteries for trade, hunting, and war parties. [58] The landscape through which these trails passed was vastly different from that of the late-twentieth century. Hardwood forests covered much of the region, with only 13 percent of the future state's area given over to prairie. Fowl and game were plentiful, and agriculture provided a principal means of sustenance as well, most notably cultivation of maize, beans, squash, and melons. The fur trade, however, caused overtrapping, initiating a process of ecological imbalance that would have far reaching implications for the Native American tribes. Forced to travel ever greater distances to acquire the pelts they needed to trade for European goods, tribes such as the Miami became involved in trade networks that skewed their traditional lifeways and subsistence patterns. The transformation of Indian cultural practices brought on by the fur trade reached even more deeply than a desire for technologically superior manufactured goods. The symbolic value of European goods was held in equally high regard. European glass beads could be likened to native crystals for their ceremonial use, and mirrors, like water, were useful for divination rituals. Consequently, a process began in which European items gradually began to supplant traditional native materials for many rituals. Perhaps the most vivid was the widespread use of iron tools, knives, kettles, and necklaces of beads in burial ceremonies, often in dramatically greater amounts than grave goods had been provided in the precontact period. Such instances illustrate that, within Indian culture, the symbolic value of these materials in the social and political realms often outstripped their utilitarian value. [59]

The rich symbolism with which Indian tribes endowed European goods influenced their approach to maintaining trade networks as well. In many instances, the French developed close, even paternalistic, relationships with the Indian tribes with whom they traded. The devastation wrought by epidemics and displacement from their traditional eastern territory led tribes such as the Miami to welcome such relationships, as they buttressed the primacy of social relationships in their traditional systems of exchange while also bringing them into the sphere of a much larger world economy. Ironically, the paternalistic role did not translate into greater cultural hegemony for the French, but instead obligated them to mediate conflicts amongst the tribes and provide material goods to those in need. [60]

Expansionist pressure from the English colonies on the Atlantic coast and British efforts to control the fur trade disrupted the status quo by the mid-eighteenth century. Escalating episodes of conflict culminated in the French and Indian War, which began in 1754 and ended early in 1763. Defeated, the French surrendered their claims to the Northwest Territory in the Treaty of Paris. However, renewed Indian resistance to European influence left British control of the territory often tenuous. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that, in their relations with the resident Indian tribes, the British enjoyed a lesser degree of success than had the French at establishing productive trade networks. In a misguided attempt at economy, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, British commander-in-chief, ordered his western commanders to limit the provision of gifts, ammunition, and liquor to Indians. Such measures made the British appear ungenerous and inhospitable in the eyes of Native Americans, and had the disastrous consequence of disrupting commerce throughout the Great Lakes region. Frustrated tribes turned to armed reprisals, under the leadership of the Ottawa war chief Pontiac. [61]

Pontiac's War soon devolved into a conflict of attrition, with various tribes laying siege to Detroit and military outposts along the Wabash and Maumee rivers. Belated word of the Treaty of Paris, in which the French abrogated their claims to the Northwest Territory, proved demoralizing to the Indians. A stalemate occurred, with the Native American tribes ultimately conceding that the British might prove as adept as the French had been in maintaining beneficial relations. The replacement of General Amherst with Sir William Johnson, who saw to it that trade goods and gifts flooded into the Great Lakes region, helped ease the sting of military defeat. Furthermore, in an attempt to maintain peaceable relations with the Native Americans, a royal decree issued in 1763 forbade white settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. The Quebec Act of 1774, which incorporated the territory north of the Ohio River into the Province of Quebec and forbade immigration from the eastern seaboard colonies, was another attempt to limit settlement in the region. [62] Enforcement of the proclamations proved almost impossible; however, and the incursions of land speculators and squatters not only continued, but increased west of the mountains.

The undoing of British aspirations in the Indiana territory, however, lay in the monarchy's growing rift with its American colonists. The British failed to maintain control over land speculation and the revenue generated by trade networks, and overextended themselves by dint of the enormous territory they sought to control from a distance. Consequently, they proved unable to maintain either a strong military presence or a coherent bureaucratic process for trade, governance, and land transactions. [63] These difficulties left the British poorly equipped to follow up the military victories of the French and Indian Wars. At the outbreak of the American Revolution, in 1775, there was no British garrison in all of Indiana.

In 1777, British commanders belatedly sent temporary garrisons to the region with explicit orders to incite Indian attacks on American frontiersmen. Such a charge was not difficult, as many Indian tribes had grown increasingly alarmed by the rapid influx of white settlers and the increasing stridency of land speculators determined to acquire huge tracts of land. The year 1777 became known as the "bloody year," as a result of the ensuing Indian attacks. Atrocities were committed by combatants on all sides producing an enduring legacy of hatred and fear between Native Americans and American settlers. [64]

Under the leadership of George Rogers Clark, an American expeditionary force won a decisive American victory over the British at Vincennes on February 25, 1779. Thereafter, the two sides stood at a military stalemate in the Northwest Territory until the American victory at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. [65] During the ensuing peace treaty negotiations, one of the most important issues was the location of the boundaries of the United States. Eventually, the British conceded designation of the Mississippi River as the western boundary, a major victory for the newly recognized nation.

Other parties, however, were not prepared to accept the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The Miami, Shawnee, and other tribes that occupied the Northwest Territory were not parties to the negotiation and saw no reason to recognize its legitimacy. French inhabitants, many of whom were descendants of the region's earliest French explorers, were also wary of American intentions. Additionally, the British proved reluctant to surrender their forts and outposts to the upstart nation. [66] Americans, on the other hand, quickly came to regard the Northwest Territory as theirs to exploit in whatever manner they deemed appropriate.

EXPANSIONISM BY THE UNITED STATES (1785-1815)

Three major problems confronted the United States with regard to the disposition of the Northwest Territory: Indian resistance; a lack of an orderly and democratic system to transfer land ownership from government to private hands; and a system of government for the territory. The most immediate and critical of these issues was that of Indians' insistence that the land in question remained under their hegemony rather than that of the United States.

Following a series of poorly managed diplomatic missions and military adventures, the Indian tribes of Ohio and Indiana allied into the Miami Confederacy (led by Chief Little Turtle), in an effort to slow the influx of American settlers and defend against further military incursions. With British encouragement, fierce raids on American frontier settlements succeeded for a time in drastically reducing the influx of new settlers along the Ohio River. The defeat of an American force under the command of General Josiah Harmar by Shawnee and Miami warriors at the Maumee and St. Joseph rivers in 1790 bolstered the native confederacy's resolve. This was further enhanced by the route of American military forces led by General Arthur St. Clair near present-day Portland, Ohio, in 1791. [67]

Indian resistance to American incursions stemmed from a number of important cultural differences. First and foremost, the Americans appeared cheap compared to their predecessors, the British and French. Federal agents did not distribute gifts or engage in ceremonies that signaled recognition of Indians as equals. This was partially due to the fact that the newly formed government had little money, but more importantly, it reflected an American ideology with regard to the Northwest Territory. Americans had little interest in establishing relations or trade networks with resident tribes as the French and British had. Instead they sought to transform utterly land uses in the region. In American eyes, the territory was destined to be rearranged into an agrarian landscape peopled by independent farmers. If they wished to stay, Indians would have to surrender their traditional lifeways and mirror the customs and social organization of Americans. [68]

Americans also proved unable to bridge an ideological divide between themselves and Native Americans. They had little interest in assuming the paternalistic role undertaken by the French and, to a lesser degree, the British. The republican ideology born of the American Revolution rejected such ties of dependency. "Liberty" meant the ability to behave autonomously, independently and freely, without fealty owed to kings, priests, aristocrats, or any other ruling class. The inherent contradictions in the republican ideology, particularly with regard to the institution of slavery, were conveniently ignored, at least when it came to the Federal government's dealings with Indians. Ultimately, it was the unpredictability of the Americans that proved most unsettling to their Indian counterparts. Having no sense of the ritual of mutual obligation and personal reciprocity, which had defined Indian relations with European powers, the Americans posed a far greater threat to Indian sovereignty and society. Their rhetoric and behavior demonstrated that the future they planned for the Northwest Territory held little room for Indians in any role. [69] The various Indian tribes, particularly the Miami, Wea, Shawnee, Piankashaw, and Delaware, responded to this threat with military reprisals.

The momentum of Indian victories proved to be short lived. In the summer of 1794 an American force under the command of Anthony Wayne defeated the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on the Maumee River. The American triumph led to negotiation of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The defeated tribes ceded control of the southern two-thirds of present-day Ohio and a narrow strip of southeastern Indiana. Although the treaty clearly established the boundaries for legal settlement in Indiana, American squatters penetrated further west in increasing numbers, representing the first wave of a rising tide of immigration. [70]

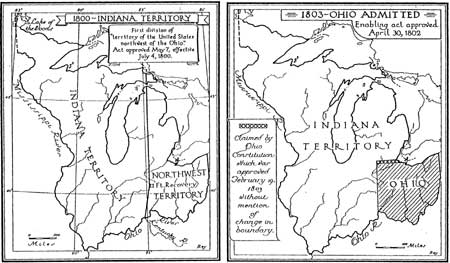

In 1800, the U. S. Congress approved the division of the Northwest Territory into the territories of Ohio and Indiana. Indiana Territory encompassed an area bounded on the east by the Northwest (later Ohio) Territory, on the south by the Ohio River, on the west by the Mississippi River, and on the north by the Canadian border (Figure 6). Vincennes was designated the territorial capital. [71] This demarcation of boundaries was made in accordance with the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris despite the continuing refusal by Indian tribes to recognize the legitimacy of the treaty's terms.

|

| Figure 6: 1800 and 1803 Maps of Indiana Territory (Buley, 1950:1:62) |

LAND CESSIONS BY INDIAN TRIBES

|

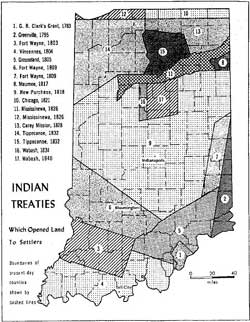

| Figure 7: Indian Treaties and Land Cessions (Sieber and Munson, 1994: 22) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Subsequent to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson conceived the idea of removing all Native American tribes to a "sanctuary" west of the Mississippi River. This notion had the added advantage of addressing the persistent problem of the tribes' rejection of the Treaty of Paris. William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, acted as the principal agent in negotiating a series of treaties with the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Miami tribes whose goal was the displacement of the Indians to western territories (Figure 7). Through "aggressive use of threats, trickery, and bribery, creating and capitalizing on tribal dissensions, Harrison, in treaty after treaty, gained the cession of millions of acres of Indian lands." [72] Negotiated in rapid succession over the next several years, these treaties included the 1803 Treaty of Fort Wayne, which granted the United States a portion of southwestern Indiana; the 1804 Treaty of Vincennes, which encompassed an area immediately north of the Ohio River; and the 1805 Treaty of Grousland, which took in territory in southeastern Indiana. Two years later, the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne further expanded American holdings in southeastern and southwestern Indiana.

By this date Native American resistance to American expansion had become more organized than at any time since the early 1790s. Beginning in 1806, elements of the Shawnee, Wyandotte, Potawatomi, and other tribes began gathering at Prophet's Town on the north bank of the Wabash River, creating a geographic focus for the growing unease with which the Native American population held the United States. Indian resistance was organized by the visionary Shawnee leader Tecumseh, aided by a revitalization movement led by his half-brother Tenskwatawa (the Prophet). In 1811, Tecumseh traveled through the mid-south attempting to garner support for a united native opposition to American encroachment. While Tecumseh was gone, Prophet's Town became a target for an American military incursion under orders from President James Madison. The invasion culminated in the Battle of Tippecanoe, fought November 7, 1811. [73] Although the Americans won the battle and destroyed Prophet's Town, the Native American resistance continued with British aid throughout the period known as the War of 1812.

Indian raids on frontier settlements continued, coupled with the outbreak of armed conflict between the United States and Great Britain. Of the major Indian tribes residing in the Northwest Territory, only the Miami chose to remain neutral. The United States suffered a series of military defeats during 1812, including the loss of Detroit and Fort Dearborn. Indian assaults against settlers took place throughout Indiana and forced the abandonment of outlying (illegal) American settlements. Attacks against Fort Harrison and Fort Wayne also took place. Harrison resigned his commission as governor of the Indiana Territory and took command of the northwestern American army. In October 1813, his forces defeated the British and their Indian allies at the Battle of the Thames. [74] The war continued for two more years, culminating in United States victory against the British at the Battle of New Orleans. In negotiating the peace treaty, the United States and Great Britain agreed to restoration of the status quo antebellum with regard to territorial relations. Longstanding matters of dispute concerning claims to territory that dated back to the 1780s also were resolved, thus securing American rights to exploit the Northwest Territory without interference from European powers. [75]

As for Indian resistance to American expansionism, Tecumseh was among those killed at the Battle of the Thames. Meanwhile, Tenskwatawa's credibility had largely been destroyed by his loss at the Battle of Tippecanoe and he ultimately migrated to Canada. The loss of the two Indian leaders spelled the end of organized, united Indian resistance to American expansion into the Northwest Territory. Aside from their military and technological advantage, the sheer scale of the environmental, economic, and demographic transformations the Americans brought to the region proved overwhelming. [76] In the two decades following the War of 1812, the Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware were forced to surrender their remaining claims in Indiana. The fact that, unlike other tribes, the Miami had remained neutral during the War of 1812 was given little credence by the United States.

The trend of major land cessions by Indians began with the Maumee Treaty of 1817, in which a small area of northeastern Indiana, adjacent to the Ohio border, was ceded. The following year, a treaty signed at St. Mary's in Ohio by representatives of the Delaware, Miami, Wea, and Potawatomi surrendered title to about 8 million acres and became known as the "New Purchase." The lands of the New Purchase included most of what is now central Indiana, and these lands were legally opened to settlement in 1820. Thereafter, smaller tracts in northern Indiana were signed over in a succession of treaties: the Chicago Treaty of 1821, the Mississinewa Treaties of 1826, the Carey Mission Treaty of 1828, the Tippecanoe Treaties of 1832, and the Wabash Treaties of 1834 and 1840.

The first American settlement in southern Indiana was near the modern site of Clarksville. It was sited on Virginia military grant lands provided to the officers and men who had participated in the battle at Vincennes under Clark's command. Legal settlement in the remainder of southern Indiana became possible as a result of the treaties of Greenville (1795), Vincennes (1804), and Grouseland (1805). Spencer County was part of the territory ceded by the Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware tribes with the Treaty of Vincennes. The first federal land survey of this area took place in 1805-1806, and the first legal land entry at the federal office in Rockport was made by Daniel Grass in May 1807. [77] Hostile relations with resident Indian tribes remained problematic for more than a decade thereafter. Additional issues facing settlers in the Northwest Territory were the need to create a method for administering land sales on a large scale and of establishing a system of governance for the area. Addressing these problems required an intensive effort on the part of the Federal government equivalent to that applied to relations with Indians.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/hrs/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003