|

Lincoln Boyhood

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER V:

Settlement and Immigration

The conclusion of the War of 1812 removed the British as a permanent presence in the Northwest Territory and greatly reduced Indian resistance to white settlement in the region. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, American settlement required resolution of several critical issues. Land surveys, administration of land sales, and establishment of a system of governance had to be established in a manner that both satisfied would-be settlers and addressed the competing claims of various state governments and land speculators. Moreover, the newly created United States government was anxious to take advantage of the region's untapped economic potential. Under the Articles of Confederation, land sales were one of the few ways available for the national government to generate revenue. The United States Congress responded to these issues with a series of legislative acts that created a rational system for organizing and settling the territory, transferring land ownership from public to private hands, and admitting new states into the Union.

FEDERAL LAND LAWS (1785-1820)

Prior to the 1780s, four eastern states claimed portions of the Northwest Territory on the basis of language in their colonial charters. The most tenuous claim was New York's. Under its 1699 charter, New York was granted guardianship over the members of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois had once included part of the Northwest Territory in their sphere of influence, a state of affairs that had become irrelevant by the late eighteenth century. Consequently, New York ceded its claim to western lands in 1780. Virginia, on the other hand, had the strongest claim to the Northwest Territory, since Virginia's 1609 charter granted it authority over all of the Northwest Territory, as well as portions of present-day Pennsylvania and Kentucky. The commonwealth assumed a large share of responsibility for the military protection of the area during the American Revolution, providing most of the soldiers and material that allowed George Rogers Clark to complete his successful campaign in Vincennes in 1779. In exchange for a reserve of land between the Scioto and Little Miami rivers in eastern Ohio, Virginia agreed to surrender its claims to the remainder of the Northwest Territory; an offer accepted by Congress in 1784. The claims held by Massachusetts to the Northwest Territory were settled in 1785. A year later, Connecticut, too, won a concession of a reserve of land in present-day Ohio. Located in northeastern Ohio, the Western Reserve lay between Lake Erie and the forty-first parallel, and extended 120 miles west from the Pennsylvania border. [78]

|

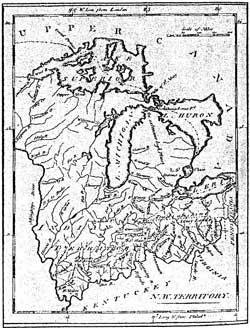

| Figure 8: Map of the Northwest Territory as Established by the Ordinance of 1787 (Day, 1988: 28) |

With the issue of western land claims by eastern states resolved, the Federal government possessed all the 265,000 square miles encompassed by the Northwest Territory (Figure 8). Thomas Jefferson headed a committee appointed by Congress to devise a system of government for the area. A revised version of his committee's report, known as the Ordinance of 1784, was passed by Congress in April 1785. The legislation called for the eventual creation of ten states from the area. Upon attaining a population of 20,000 residents, each prospective state would be admitted to the Union. This was the first concrete evidence of the Federal government's intention to treat newly established states on equal terms with the original thirteen states. The Ordinance of 1784 also formalized a number of other basic principles. The new state governments were required to swear permanent allegiance and subordination to the United States; respect the boundaries of Federally owned lands; exempt Federal lands from state taxation; assume a proportional share of the national debt; commit to republican forms of government; and tax resident and nonresident landowners at the same rate. Formal strategies for accomplishing these principles were not laid out in the Ordinance of 1784. Nevertheless, this served as a declaration of Federal authority over the region, with the interests and agents of the United States held supreme above all others. [79]

THE LAND ORDINANCE OF 1785

Congress established its first public-land policy for the administration and sale of Northwest Territory lands with the Land Ordinance of 1785. This law established that all land would be surveyed into townships with an area of six square miles as soon as questions of Indian title were resolved. Each township would include 36 sections, each containing 640 acres. [80] The survey was to begin at the junction of Pennsylvania's western boundary with the Ohio River and continue westward. A portion of the Northwest Territory, approximately one-seventh of the total area, was set aside to pay bounties to American Revolutionary War veterans. The legislation also required that one section in each township be set aside for the purpose of establishing and maintaining a public school, marking the first time that the issue of public education was addressed at a national level. Remaining sections of land were to be sold in 640-acre tracts at public sale for not less than one dollar per acre. [81]

The task of surveying the Northwest Territory was enormous. The work was carried out by hand, and the entire countryside, including swamps, cane breaks, and marshes, was crossed. A survey crew typically consisted of a deputy surveyor, responsible for directing the operation with the use of a magnetic compass; two chainmen, who stretched the traditional four-rod measuring chain on the survey line; at least one flagman to mark the spot toward which the chainmen worked; one or two axmen who cleared the line of vision and blazed corners; and perhaps a hunter and a cook. Although the task was physically arduous, many men competed for surveyors' jobs, since it offered them an opportunity to scout the best land in a given area. [82]

Surveyors oriented each tract to lines of latitude and longitude based on an arbitrarily placed north-south meridian and an east-west baseline. Numbered range and township lines, running parallel to the meridian and base lines, established the grid of six-mile-square townships. Townships then were divided in the same fashion. Thomas Jefferson has been credited with developing this rationalist approach to surveying, which differed sharply from traditional approaches that relied on the placement of natural features for orientation and measurements. Subsequent legal descriptions for land ownership throughout the Northwest Territory were based upon these land subdivisions. This orderly system was modeled after the New England plan of prior survey, township platting, and granting of a deed in fee simple, and encouraged controlled development and a more compact pattern of settlement. [83] et Faragher points out that "a persistent traditionalism" was evident in the surveying efforts. Principal meridians usually were started at the mouths of rivers, which played a critical role in the penetration of the Northwest Territory's interior, instead of relying on pure geometry. Township sections were numbered in oscillating rows from left to right and then right to left, in the same fashion as a plow criss-crossed the land. Jefferson's suggestion for use of a decimal system of measurement was, however, overruled in favor of the traditional 66-foot chain, which allowed incorporation of the traditional rod, acre, and statue mile measurements familiar to most nineteenth century Americans. [84]

This Federal survey method stood in sharp contrast to the more haphazard approach that prevailed in the territory south of the Ohio River, which relied upon a convoluted system of warrants, certificates, caveats, and grants that often obliterated a clear chain of title. The goal of the Federal system was to encourage purchase of land by converting untracked wilderness into an easily traded commodity. The required minimum purchase of 640 acres, however, promoted speculation and precluded many prospective settlers. In response, some established homesteads on land without formally purchasing it, becoming squatters. [85]

Such illegal settlement in the Northwest Territory had been a significant problem for some time, notwithstanding the hostilities engendered by the American Revolution and ongoing Indian resistance to white settlement. The Federal government viewed squatting with considerable hostility for several reasons. The presence of squatters conveyed a sense of weakness and inefficacy on the part of the United States, since they demonstrated its inability to control territory over which it claimed dominion. Deeply in debt and with minimal resources, the fledgling government further feared that a rapid influx of squatters would provoke warfare with the resident Indian tribes that had so recently allied themselves with the British. [86] Conflicting popular views of squatters were held. Easterners, for the most part, tended to regard squatters as opportunistic and lawless, while Westerners tended to consider them independent, enterprising, and adventurous.87 These disparate opinions highlighted both regional differences already emerging in the nascent nation and, perhaps, class conflict between entrenched property owners and the landless.

THE NORTHWEST ORDINANCE OF 1787

With passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Congress established a formal system of governance for the Northwest Territory. The legislation established a single government for the entire territory, with provision for the eventual creation of three to five smaller territories. Each territory would initially be governed by a governor, secretary, and three judges, all of whom were to be Federally appointed. When the population numbered 5,000 free adult males, a bicameral territorial legislature was to be formed. When the total population in the territory numbered at least 60,000 the territory could apply for statehood on an equal basis with the original thirteen states. [88] Significantly, slavery was prohibited in the Northwest Territory, a condition that would have a significant role in the evolution of the balance of power between free and slave-holding states over the course of the early- to mid-nineteenth century.

As had been the case with the Ordinance of 1784, the Northwest Ordinance reiterated the supremacy of the United States government's authority over the territory. In essence, according to Cayton, the 1784, 1785, and 1787 ordinances "entailed nothing less than the complete transformation of the region . . . they assumed the adaptation of the Indians, the French, and the natural landscape to the economic and political imperatives of the United States." [89] As such, the Northwest Territory was to serve as an incubator for the political experiment begun with the American Revolution.

Working to the advantage of the United States in its quest for dominion over the Northwest Territory was the existing power vacuum in the region. Construction of military forts heralded the arrival of Federal power, and the army acted as the primary agent for expressing Federal policies to the area's residents, including Indian tribes, French residents, lingering British troops in remote outposts, and illegal settlers. With a few notable exceptions, the Indians displayed an inability to unite against Federal incursions into territory they still regarded as their own. Wartime privations had left the French disillusioned with the British and Virginia (whose government had assumed responsibility for the region during the Revolution). The British were proving reluctant to abandon their northwestern posts, in violation of the terms of the Treaty of Paris. Settlers, finally, were too few and had no legal standing in the region. In the absence of effective opposition, the United States was able to convey the illusion of being both a dominant force and an arbiter of disputes among the various parties, primarily through the actions of its military and the territorial government. [90]

The first governor of the Northwest Territory under the 1787 ordinance was Arthur St. Clair. A Scotsman whose career included military service in the French and Indian War, service on George Washington's staff during the American Revolution, and a stint in Congress, St. Clair proved an unpopular choice for the position. His condescending manner and propensity for arbitrary judgements led many to liken his manner to that of the royal governors prior to the Revolution. The 1791 defeat of military forces under his command by Indian tribes further eroded his reputation. He remained, however, governor of the territory until 1798, when a sufficient population was achieved to divide the region into two territories. The eastern division ultimately became the State of Ohio in 1803. The western division was the Indiana Territory, and extended from the west boundary of Ohio to the Mississippi River, and north from the Ohio River to the Canadian border. [91]

THE LAND ACT OF 1800 AND THE INTRODUCTION OF A CREDIT SYSTEM

Disposition of land remained a critical issue in the Northwest Territory in the late 1790s. Jay's Treaty of 1796 finally resolved the lingering issue of British outposts in the region. The Greenville Treaty cleared title to the southern two-thirds of Ohio, as well as approximately 25,000 square miles in southeastern Indiana. With this resolution of two significant obstacles to legal settlement, and with illegal settlement continuing at a rapid rate, the question of administration of land sales north of the Ohio River was again raised. In 1796, Congress passed new legislation to address land sales, but made few changes to the procedures established in 1785. The rectangular system of surveying was made permanent. The price per acre was increased to two dollars, while the minimum land purchase remained 640 acres. Sales continued to be made at public auctions in the East, with prospective settlers often bidding against speculators with much deeper capital reserves. Under the leadership of William Henry Harrison, who served as congressional delegate for the Northwest Territory during the 1790s, Westerners began to lobby increasingly for smaller tracts, lower prices, a credit system, and preemption rights. [92]

Congress eventually responded with the Land Act of 1800. This law created a system for the relatively simple, legal acquisition of Federal land by private individuals. To administer the process, four land sale offices were opened within the Northwest Territory, at Chillicothe, Marietta, Steubenville, and Cincinnati. Each office included a staff of two officers; a registrar who recorded applications and land entries, and a receiver who handled financial transactions. A credit system was introduced. Although the price remained two dollars per acre and the minimum purchase remained 640 acres, an applicant had forty days to pay one-fourth the total price, two years to pay another quarter, three years for the third quarter of the purchase price, and four more years to retire the debt. An interest rate of 6 percent was levied on these credit arrangements. [93]

The legislation proved successful in encouraging more rapid settlement of the Northwest Territory. By the end of the first year under the act, 398,646 acres of land had been sold, at a price of $834,887. With the exception of 1803, sales increased annually each year thereafter, with the peak level of activity taking place in 1805, when 619,266 acres were sold for almost $1.26 million. [94] This was the year that land in southern Indiana was opened to legal sale for the first time. Although a fair amount of land speculation took place, it generally did not involve large parcels, and less than 10 percent of the land sold in southern Indiana went to speculators. [95]

The increased level of sales in 1805 resulted from passage of the Land Act of 1804, which reduced the minimum purchase amount to 160 acres, and the establishment of additional land offices at Detroit, Vincennes, and Kaskaskia. Interest was no longer charged to purchasers until after payment was due and several processing fees were also abolished. [96] This law remained in force for sixteen years, with an amendment in 1808 that raised the price per acre to four dollars. It was this legislation under which Thomas Lincoln filed for his farmstead in Spencer County. Additionally, as previously noted, during this same period, Indiana's territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, negotiated a series of treaties that resulted in Indian cessions of vast tracts in Indiana. These included the 1803 Treaty of Fort Wayne, the 1804 Treaty of Vincennes, the 1805 Treaty of Grouseland, and the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne. With these agreements, legal settlement became possible throughout the southern third of Indiana.

In the midst of this progress two critical issues developed that threatened the system of land sales in the Northwest Territory. Thousands of individuals had purchased more land than they could afford, and their forfeitures threatened to destabilize this important source of revenue for the Federal government. In addition to the potential loss of revenue, forfeitures placed the government in the position of initiating unpopular evictions and forfeitures upon settlers in areas where Federal authority remained thinly stretched. Second, national political policy affected the credit system. American trade embargoes against European nations drastically reduced demand for agricultural products, and exports fell from an approximate $30 million annual average at the turn of the century to $5 million by 1808. Congress responded to both these problems with a series of relief acts aimed at preventing forfeitures among farmers and preserving the credit system. [97] These were generally stopgap measures that temporarily eased the financial crisis without addressing the systemic faults causing the credit system to fail.

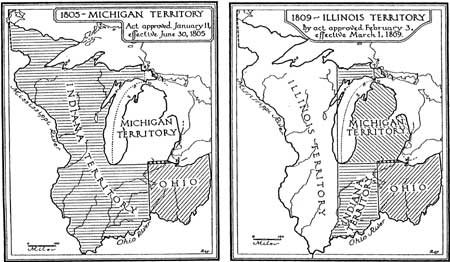

The Land Act of 1800 and the introduction of a credit system had the indisputable consequence of encouraging a steadily increasing rate of settlement in the Northwest Territory during the first decade of the nineteenth century. Along with the growth in population and the penetration of white settlement into the interior, the territorial government matured. In 1805, Michigan Territory was created from Indiana, and in 1809 the Illinois Territory was split off, thus establishing Indiana's present boundaries (Figure 9). Appointed by Thomas Jefferson, Harrison served as Indiana's governor from 1800 to 1813. [98] During this period, Indiana passed through the first two stages of government specified in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787: first, rule by a governor, secretary, and three judges (appointed by the President) and, second, by a bicameral legislature with representatives elected by a landed class of voters.

|

| Figure 9:Map Depicting Separation of Michigan and Illinois Territories (Buley, 1950: 1:63) |

Effects of the War of 1812

|

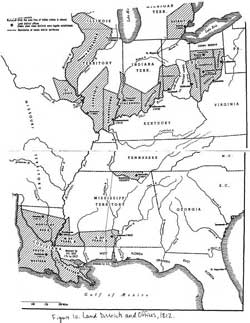

| Figure 10: Land Districts and Offices, 1812 (Rohrbough, 1968) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The outbreak of the War of 1812 had very little impact on the rate of settlement in the Northwest Territory, despite the fact that armed conflicts with British soldiers and their Indian allies necessitated the abandonment of some outlying posts and farms. In Spencer County, for example, the Meeks family in Luce Township was attacked by an Indian war party in May 1811, and William Meeks was killed. Raids by Indians also hampered Federal surveying efforts. By 1812, the southern third of Indiana and Illinois had been surveyed, but of the 2.8 million acres in southwestern Indiana acquired under the terms of the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne, the majority remained unrecorded as late as 1815. Nevertheless, a total of 324,000 acres in Indiana were sold at public auction between 1811 and 1814. Settlement advanced northeast from Vincennes along the White River, and northwest from the Ohio border along the Whitewater River. Between 1810 and 1815, Indiana's population increased from 24,520 residents to 63,897. Federal land offices established in Vincennes (1804) and Jeffersonville (1812) administered the sale of land (Figure 10). [99]

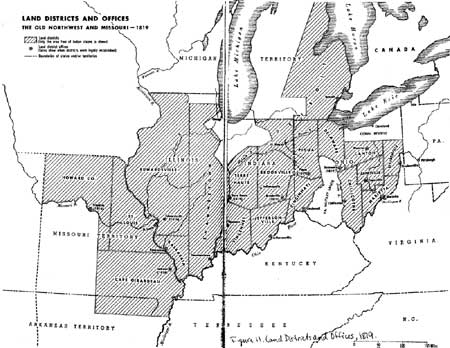

Following the end of the War of 1812, the rate of settlement increased at an exponential rate. With Indian resistance broken, what has been termed the "greatest westward migration in the history of the young nation" took place. [100] Land sales at the Federal office in Jeffersonville increased by 30 percent from 1815 to 1816. During the same period, sales increased a staggering 425 percent at the Vincennes office. In 1817, sales at Vincennes totaled more than 286,500 acres at a price of $570,923, while Jeffersonville brought in $512,701 for 256,350 acres. To facilitate land sales in central and northern Indiana, Federal land offices also were established in Brookville and Terre Haute in 1819 (Figure 11). By 1820, the United States had collected almost $5.14 million from the sale of over 2.49 million acres. Approximately 42,000 people are believed to have immigrated to Indiana in 1815 alone, and from 1810 to 1820, Indiana's population more than quintupled from 24,520 inhabitants to 147,178. The massive demand was partially due to the relative cheapness of land in Indiana, especially compared to Ohio, and the rampant land speculation and muddying of titles occurring in Kentucky. Nationwide economic prosperity, an open and flexible banking system, and rising prices for agricultural products, propelled the westward movement as well. [101]

|

| Figure 11: Land Districts and Offices, 1819 (Rohrbough, 1968) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The population explosion in the Northwest Territory was sufficient to allow the creation of five new states, including Indiana, between 1816 and 1821. [102] Statehood for Indiana had been proposed as early as 1811 by the territorial assembly. Congress passed the enabling legislation for Indiana's petition for statehood in April 1816. A state constitutional convention took place two months later. Constitutions from the neighboring states of Ohio and Kentucky served as models for Indiana's, as did the United States Constitution, with its Bill of Rights and system of checks and balances on government power. Indiana's 1816 constitution divided power among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government, with the lion's share of power concentrated in the hands of the legislature and, at the local level, in county officials. The franchise was limited to white males at least twenty-one years of age and residents of Indiana for a minimum of one year. The state constitution also incorporated Revolutionary-era concepts of individual liberty and freedom of worship, speech, the press, and assembly. [103]

Several progressive elements also were included in Indiana's first constitution. A system of free public education was established, as well as a penal system based on reformation of prisoners rather than merely punishment. The issue of slavery also was addressed. The institution had been established in Indiana by French settlers concentrated around Vincennes during the early- to mid-eighteenth century. Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 specifically forbade slavery, the territorial government under St. Clair and Harrison had allowed indentured servitude to continue in various guises. In 1802, Harrison made a failed attempt to have the ban upon slavery lifted, arguing that it would attract more settlers to the area. Anti-slavery forces ultimately prevailed, and Indiana's 1816 constitution confirmed that slavery was illegal in the state. The provision was not made retroactive; however, and 190 slaves were recorded in the 1820 census of Indiana. Shortly thereafter, the Indiana Supreme Court issued several decisions that made slavery and indentured servitude illegal in all instances. [104]

Indiana's constitution went into effect on June 29, 1816. Elections took place in August for the state's first General Assembly, and the first governor, Jonathan Jennings, was elected. In December 1816, President James Madison signed the congressional resolution that admitted Indiana to the Union as the nineteenth state.

The Panic of 1819

Statehood led to a reduced Federal presence in the region, particularly with regard to the military. The emphasis of government passed from the maintenance of security and protection against hostile powers to economic development, particularly via public land sales. Congress had created the institutional framework for achieving this objective with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the various Federal land laws passed between the 1780s and 1805. The first pioneers in the region built upon this administrative structure, creating processes and institutions that suited American goals for transforming the landscape of the Northwest to suit their needs. These constituted the processes followed by the vast majority of settlers in the Northwest who reached the region between 1810 and 1830. Consequently, by 1815, the frontier experience had become increasingly orderly, standardized, and cyclical. [105]

Public land sales were the engine that powered development within Indiana, and this process continued to be controlled by the Federal land offices established throughout the Northwest. As the chief administrator for placing huge quantities of land on the market and recording sales, the land agent stood at the center of the Federal bureaucracy, hiring clerks and survey crews to undertake the arduous chore of surveying land and recording sales. In recognition of their influential role, land agents also occupied significant positions in frontier society and politics. As such, they became the central figures of Federal authority in the Northwest. [106]

The methodical and systematic distribution of land from the public domain to private hands suffered a major setback with the national financial panic in 1819. After the War of 1812, unfettered circulation of currency without specie guarantees by the Second Bank of the United States and state-chartered banks created rapid inflation and fictitious values on everything from land and agricultural produce to manufactured goods. When the Bank of the United States was forced by administrative necessities to require guarantees of currency with specie, it was discovered that many state banks lacked the monetary resources demanded. Much of the circulating currency, in essence, proved worthless. The United States Treasury began to refuse acceptance of the currency for discharge of debts, unhinging the credit system through which the majority of settlers had acquired land in the Northwest Territory. Scrambling to remain financially solvent, state banks called in loans of all types, consequently depressing trade and stultifying market activity throughout the country. Rapid deflation, economic depression, forfeitures, and defaults on taxes followed in rapid succession. [107]

Reversions of land to the United States in 1819 totaled 365,000 acres, of which 153,000 were located in the Northwest Territory. The following year, the unpaid balance due on land sales reached more than $21 million, an amount equal to more than one-fifth of the total national debt. Of that amount, $6.6 million was for land in the Northwest. The situation was made more critical by a slump in agricultural prices. In 1820, the value of export products from the Ohio Valley was only half what it had been the year before. [108] Congress eventually responded to the crisis with two pieces of legislation: the Land Act of 1820 and the Relief Act of 1821.

THE LAND ACT OF 1820

Passed by Congress on 24 April 1820, the Land Act of 1820 abolished the credit system and required cash sales for public lands after 1 July 1820. The law has been called "the single most important piece of land legislation since the original 1785 ordinance," since it created "the most liberal provisions [for buying title to land claims] in the history of the republic." [109] Tracts as small as 80 acres were made available at a cost of only $1.25 per acre. Only $100 was needed to gain clear title to 80 acres of land, whereas, under the credit system, $80 had been required to make just a one-fourth payment on 160 acres. The new law consequently made land purchases more affordable than ever before to a broader spectrum of the American public. Further, it helped quell land speculation, even in the aftermath of numerous forfeitures brought on by the financial difficulties associated with the Panic of 1819. [110]

The 1820 land law did not address the $23 million in land debt that resulted from overextended buyers and the 1819 panic. Many Westerners petitioned Congress to provide a means of relief, especially in light of the fact that national policies concerning trade and banking practices had contributed greatly to the magnitude of the financial depression. Congress responded with the Relief Act of 1821, which allowed debtors to relinquish a portion of their land and have all previous payments applied to the remaining land. Such a measure allowed many farmers to retain ownership of their land, particularly given the limited availability of credit since 1819.

Thomas Lincoln was among many Indiana farmers who secured final title to his land under this law. Within seven months of the law's passage, the balance due to the Federal government on all lands diminished by almost one half. Subsequent relief efforts made steady progress toward eliminating the debt possible by 1830. [111]

The twin objectives of encouraging settlement in the Northwest Territory and maintaining a democratic process for land distribution dated back to the Land Ordinance of 1785. The 1820 land law and the 1821 relief act provided the final impetus required to achieve these goals. According to Cayton, this legislation made possible the completion of a remarkably egalitarian process of transferring land from one group (Indians) to another through the intermediary action of a government on a scale "unmatched anywhere else in the history of the world." During the 1820s, Indiana land offices sold 1,963,947 acres at a cost of $2.5 million. Between 1830 and 1837, a staggering 5.55 million acres of land in Indiana transferred from the public domain to private hands. In the year 1837, the Fort Wayne land office alone collected over $1.62 million for 1,294,357 acres. [112]

SETTLEMENT OF SOUTHERN INDIANA

|

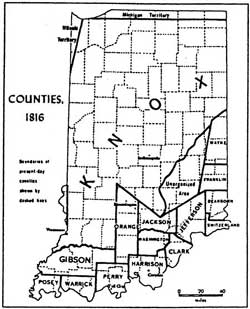

| Figure 12: Indiana Counties, 1816 (Sieber and Munson, 1994: 24) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Federal policies and treaty negotiations played a major role in the location of the earliest settlements in southern Indiana. The first legal settlement in the region was located at Clarksville, on Virginia military grant lands provided to men who had fought at the 1783 Battle of Vincennes. Squatters occupied a considerable amount of land, with upwards of 2,000 illegal settlers believed to have reached the Northwest Territory by 1785. However, ongoing hostilities with Indian tribes and Federal endeavors to control illegal incursions kept the overall number of American settlers in Indiana low. Following the American victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, resident Indian tribes ceded claims to the southern two-thirds of Ohio and a narrow strip of southeastern Indiana. Legal settlement in this area, combined with the long-established French settlements in western Indiana, brought Indiana's population to an estimated 5,641 by 1800. Further land cessions by Indian tribes occurred in 1803, 1804, and 1805 with the treaties of Fort Wayne, Vincennes, and Grouseland, respectively. [113]

Thereafter, notwithstanding the vagaries of war and financial crises, settlement of Indiana occurred with remarkable rapidity, and generally proceeded northward from the Ohio River (Figure 12). In 1800, the population was estimated to be at only 5,041 persons. By 1810, the number of inhabitants had more than quadrupled to 24,520. Within six years, the population swelled past 60,000, the required minimum number of settlers before statehood could be accomplished, and by 1820, the number had leapt to 147,178. This was the period of the Great Migration, in which, according to contemporary observers, all of "Old America [seemed] to be breaking up and moving westward." The rate of population growth slowed somewhat in subsequent decades, reaching 343,031 by 1830, and 685,866 by 1840. Settlement declined precipitously in the following decade, with only 9,080 migrants arriving, and between 1850 and 1860, 40,000 people chose to pull up stakes and move further west with the advancing frontier. [114]

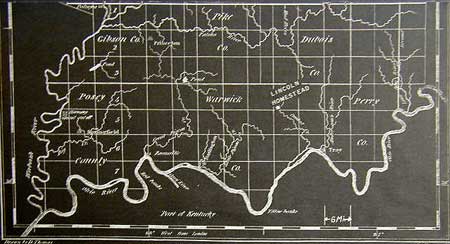

In addition to political events, geography and topography influenced the patterns of settlement and development in Indiana. The earliest historic frontier settlements in southern Indiana were clustered along navigable (and some not-so-navigable) river valleys in a U-shaped pattern, with the bottom of the U formed by the Ohio River, the eastern arm formed by the Whitewater River, and the western arm formed by the Wabash River (Figure 13). To reach the interior, settlers followed the Buffalo Trace, which crossed the Indiana Territory from the Falls of the Ohio opposite Louisville to the Wabash River at Vincennes. It has been estimated that, in 1810, 80 percent of the population lived within 75 miles of the Ohio River. Between 1810 and 1820, the area within this southern crescent filled, and by 1820 settlement reached as far north as the White River valley. The exploding population was reflected in the amount of improved land in Indiana, which increased from 125,530 acres in 1810 to 1,751,409 acres by 1830. [115]

|

| Figure 13: Map of Southwestern Indiana Taken from the Diary of David Thomas, 1816 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The origins of Indiana's settlers, their socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds, and their goals for establishing new homesteads profoundly shaped the state's development throughout the early- to mid-nineteenth century. Most of Indiana's early settlers were from the North Carolina Piedmont and the Upland South (Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee). These populations usually came to Indiana via the Ohio River or along overland routes. [116] According to Meinig, these people were part of the "Greater Virginia migration stream" that drew upon Kentucky, Tennessee, and western North Carolina. Emigration was driven partially by the astonishing rate of population growth in the United States from 1800 to 1850. The average rate of increase each decade was 33 percent, with the total population rising from 5.3 million in 1800 to almost 23.2 million a half-century later. [117] In addition to Upland Southerners, a significant number of ethnic German families moved west into Indiana from Ohio and Pennsylvania via the Ohio River, settling in the southern portion of the state, and a smaller proportion of settlers moved from New York, Maryland, and the New England states. Throughout the frontier period, southerners constituted the majority of Indiana's population; as late as 1850, less than 10 percent of the state's total population was comprised of Yankee-born settlers. [118]

The first settlers to reach southern Indiana displayed a marked preference for the uplands, colloquially known as the Knobs. This landscape displayed a number of characteristics that were familiar to Upland Southerners and desirable for early-nineteenth century agricultural practices. The hilly terrain was well drained, had plentiful springs, possessed fertile soil, and the dense forests offered plentiful game, fuel, and building materials. The uplands also had fewer pests, such as mosquitoes, and overland travel along the hillsides was immensely easier than in the lower marshlands. The bottomlands were little more than poorly drained thickets filled with briars and dense undergrowth, and prairie farming became attractive only with the development of selfscouring steel plows in the late 1830s. [119]

That many of the original settlers in southern Indiana hailed from the Upland South left a distinctive mark upon the area's cultural and social development. Upland Southerners were typically of English and Scots-Irish origin, along with some Germanic peoples. They generally were yeoman farmers who raised livestock and farmed their own land. [120] When these settlers came to Indiana, they brought with them their traditional agricultural practices; cultivating corn and raising hogs predominated in the early years. A distinctive Upland South influence on southern Indiana culture persisted for decades, evidenced by patterns of word usage and pronunciation, religion, place names, foodways, and vernacular architecture. [121]

Much has been made of the migration of Upland Southerners from the slaveholding south to the so-called free territory of the Northwest. A disdain for the peculiar institution has been supposed, but the historical record provides a conflicting statement as to the attitudes truly held by Indiana's white settlers. As previously noted, Indiana's territorial governors, St. Clair and Harrison, permitted slavery to exist in the territory, despite the ban on involuntary servitude included in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Indiana's 1816 state constitution forbade slavery as well, but the same document expressly prohibited free blacks from voting. Interracial marriage was outlawed by 1818, and blacks also were declared incompetent to serve as witnesses in a trial. The public education system, established in stages between the 1820s and 1850s, was racially segregated, with no provision made for the education of black children. [122]

Such antislavery sentiments as did exist among settlers during the early nineteenth century typically were rooted in fear that bonded labor would diminish the ability of freemen to support themselves and their families. Propertyless whites also harbored the hope that the elimination of slavery would force the breakup of large plantations and improve tenant farmers' chances to acquire land. Settlers who came to Indiana as part of the Great Migration arrived with the expectation of being able to achieve land ownership, security, and even a measure of material wealth, at least as far as could be measured by the ability to live independently on one's own homestead. [123] The various Federal legislative acts that made possible large-scale redistribution of land from the public domain to private hands directly benefited these individuals. Of these, the Land Act of 1820, which reduced the minimum unit of land to be sold at public auction to 80 acres at a cost of $1.25 per acre, was the most important. Equally important was the knowledge that Federal surveys ensured that land purchased in Indiana came with a clear title, a fact that also may have contributed to the relatively low number of squatters in Indiana, even during the frontier period. Such circumstances stood in marked contrast to the situation in most southern states, such as Kentucky, where a convoluted system of warrants, certificates, caveats, and grants often obliterated a clear chain of title and resulted in thousands of pioneer families losing the lands they had broken. Consequently, it appears that economic opportunity, rather than antislavery sentiments, appears to have been the primary motivator for Upland Southerners in their decision to relocate.

ORGANIZATION OF SPENCER COUNTY

Located between the river settlements of Louisville and Owensboro, Kentucky, and Evansville, Indiana, present-day Spencer County remained largely untouched by settlement in the first decade of the nineteenth century. The first Federal land survey of the area took place in 1805. The small village of Troy, Indiana, in neighboring Perry County was situated on the east bank of the Anderson River at its confluence with the Ohio River. Squatters settled here as early as 1800 and the locale's readily available supply of hardwood forests later attracted investors Nicholas J. Roosevelt and Robert Fulton, who established a lumberyard at the site to provide fuel for steamboats. Downriver, the tiny village of Grandview in Spencer County was settled by a group led by Ezekial Ray, and in 1803, John Sprinkle squatted on high ground east of Pigeon Creek. Uriah Lamar also has been suggested as one of the first (albeit illegal) settlers in Spencer County, making his homestead in present-day Hammond Township. Meanwhile, a cluster of cabins midway up a bluff alongside the Ohio River was known as Hanging Rock after a pair of massive columnar rock formations. Arriving in 1807, Daniel Grass changed this community's name to Mount Duvall. The same year, Grass generally is held to have made the first legal land entry in Spencer County. His homestead was located in Section 26 of Ohio Township. Approximately five years after purchasing the land, Grass and his family moved from Bardstown, Kentucky. At that time, little settlement had taken place on the Indiana side of the Ohio River, and Grass reportedly traveled to Owensboro, Kentucky, to obtain supplies. [124]

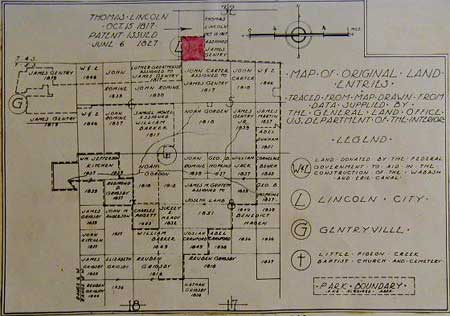

Following the end of the War of 1812, thousands of Kentuckians began to cross the Ohio River into southern Indiana. Thompson's Ferry, opposite Troy, Indiana, served as a primary entry point for many Kentuckians, including the family of Thomas Lincoln. Other river towns such as Lewisport, Hawesville, Shawneetown, Golconda, and Hamlet's Ferry also acted as conduits for the northward migration. Arriving around 1815, Thomas Carter has been credited with staking the first claim in Spencer County's Carter Township. The following year, Thomas Lincoln bought a tract in Section 32 of the township (Figure 14). Other early land entries in the vicinity were made by John Romine, Noah Gordon, James Martin, and Samuel Howell. Nearby, in sections 5 and 6 of Clay Township, original land entries were made by James Gentry, John Carter, Abel Crawford, and Reuben Grigsby, among others. All of the land in both townships had been purchased by the early 1820s. [125]

|

| Figure 14: Map of Original Land Entries in Vicinity of Lincoln Farmstead (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Spencer County's first settlers exhibited the previously noted preference for settling first on the Knobs and on the margins of forests. Such a landscape would have been familiar to settlers from Kentucky, and the proximity of the forests provided a ready supply of fuel and building materials. Numerous hilltop springs offered a convenient water source. The wetter bottomlands were generally considered to be breeding grounds for malaria, and the poorly drained soil was believed to be of a lesser quality than that of the uplands. Land entries for the county from 1807 to as late as 1830 show a consistent avoidance of the bottomlands, which did not begin to come under cultivation until the 1840s and 1850s. [126]

Indiana achieved statehood in 1816, and just one year later, all six counties on the state's southern border had been formed. Warrick County was the earliest, having been organized in 1813, followed by Perry and Posey (1814) and Crawford, Spencer, and Vanderburgh (1818). Spencer County was carved out of portions of Warrick and Perry counties. During his tenure as a state representative, Daniel Grass, who was one of the first settlers in the area, is credited with introducing the legislation authorizing the county's creation. He reportedly named the county in honor of Captain Spier Spencer, who fought at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. The county consisted of nine townships, which were settled in the following order: Ohio (1807); Luce (1807); Huff (1811); Hammond (1811), Clay (1815); Carter (1817); Jackson (1818); Harrison (1818); and Grass (1818). In late 1816, Abraham Lincoln's family settled in the area that was designated Carter Township. As the largest settlement in Spencer County, Hanging Rock (also known as Mount Duvall) was designated the county seat. Promoters platted a new village atop the bluff and dubbed it Rockport. Lots were sold beginning in June 1818. A modest amount of commercial development took place over the course of the next decade, with a tannery and a pork packing plant established by 1826. [127]

Many of Spencer County's earliest records were destroyed by fire in 1818. Nine years later, the first county courthouse also burned. [128] Information concerning the early history of the county consequently is scant. The published historical record, however, shows that during the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the northern portion of Spencer County remained thinly settled with a handful of hamlets interspersed among recently cleared farmsteads. The Pigeon Baptist Church was organized in 1816 in present-day Warrick County, and moved a short time later to Clay Township in Spencer County. The tiny hamlet of Gentryville was established in neighboring Jackson Township by 1827, and was centered around a general store operated by Gideon Romine, Benjamin Romine, and James Gentry. [129] Over the course of the next half-century, improved transportation and ongoing settlement began to ease the area's isolation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003