|

Lincoln Boyhood

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER VI:

Pioneer Lifeways

TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS

The first wave of settlers to southern Indiana generally relied upon the region's rivers and streams to move people and goods. Settlement and economic development were intricately intertwined processes in which transportation was the principal theme. As farms became established and moved beyond a subsistence level of production, transportation improvements to waterways and roads proved critical to their ability to access the national market economy. While rivers and streams initially served as the primary transportation corridors, a network of local roads developed along the system of range and township lines used by the county surveyors and parallel to the waterways. The range and township system defined parcel boundaries, and it was within this imposed grid that local settlement patterning occurred, based on topography, water, roads, and community services such as mills and smiths.

RIVERS AND STREAMS

Rivers and streams comprised the first major transportation network in Indiana. Most of the state's first farms and communities were established along rivers, such as the Ohio, Wabash, Whitewater, and White. In southern Indiana, tributary streams, including the Little Pigeon Creek, Crooked Creek, Patoka River, and Great Pigeon Creek, provided routes to inland settlements. Waterways were the first and most important outlet for farmers wishing to sell surplus agricultural products in distant markets. Geography dictated that southern Indiana was oriented toward the Ohio-Mississippi river trade from the late eighteenth century through the onset of the Civil War. The Ohio River was the most significant artery for commerce, as it joined the Mississippi River and provided a direct route to New Orleans. From the port city, Indiana's agricultural products could be shipped to a worldwide market. Furthermore, it was only from New Orleans that Indiana farmers could gain access to the well-established East Coast markets. The Appalachian Mountains posed a major barrier to shipping goods overland to eastern markets in Philadelphia and New York, and rivers and streams generally flowed southwest, making it prohibitively expensive to ship products upriver. [130]

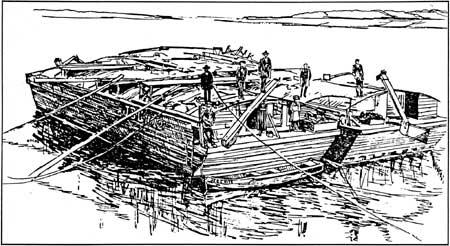

Manually powered flatboats were the primary means available to farmers for shipping their goods (Figure 15). Measuring approximately 10 feet wide and 40 feet long, the wooden boats had a steering oar (also known as "sweep") at the stern, side sweeps or poles, and often a short bow oar (also called a "gouger") for keeping the boat in the current. For the most part these vessels drifted downstream on the current; flatboats were poorly suited to upstream travel. A rough wood shelter covered the boat, shielding both crew and cargo from the elements. Cargo included agricultural products such as corn, flour, pork, honey, hay, and whiskey, as well as raw materials such as lumber and lime. [131]

|

| Figure 15: Drawing of Early Ohio River Flatboat (Sieber and Munson, 1994: 27) |

Given their small size and light draft, flatboats could navigate narrow and shallow streams, allowing farmers in the remote interior access to the Ohio River trade artery. Farmers often pooled their resources to construct a flatboat and ship their goods to market. The trip downstream to New Orleans generally required from eight to twelve weeks, depending upon weather conditions. Because the boats were so simple and inexpensive, and because upstream travel was so difficult, upon reaching New Orleans farmers usually had their boats broken up and sold for lumber and then set off for home on foot. In 1828, nineteen-year-old Abraham Lincoln was among the farmboys making the journey from the Little Pigeon Creek to New Orleans. This occasion marked the first time he left Indiana outside the company of his family. [132]

For shipping goods upstream, keelboats were the best option available in the early years of the nineteenth century. Approximately 10 feet wide and 80 feet long, the boat was pointed at both ends to facilitate travel against the current. Keelboats typically were fitted with a mast and sail, but often moved upstream by manually poling the boat against the current or by pulling it with tow ropes like a canal boat. The work was extremely laborious, and a boat with a cargo of 10 to 40 tons and a crew of 8 to 20 men generally progressed only an average of 6 miles a day. As a result, keelboats were practical only for shipping goods of low bulk and weight, or of very high value. Coffee, molasses, salt, and sugar were among the goods sent upriver from New Orleans to Indiana in keelboats. [133]

During the 1810s, river transportation was transformed by the introduction of the steamboat. Robert Fulton and his associates, including Nicholas Roosevelt, played an instrumental role in establishing steam navigation on the Ohio River. In 1811, their first steamboat, the New Orleans, traveled from Cincinnati to Louisville and back, and then continued south to New Orleans. [134] Advances in design allowed the boats to travel in shallow water and at increasing rates of speed. In 1817, a round trip from Louisville to New Orleans could be accomplished in only 41 days; within two decades, the upstream journey from New Orleans required only 8 days. Farmers also had the option of continuing to ship their goods downstream by flatboat, then making the return journey upstream via steamboat; greatly reducing travel time and permitting three or four trips a year to the New Orleans markets instead of only one. Shipping by steamboat proliferated, with the number of boats licensed for the Mississippi trade rising from 72 in 1820 to 130 by 1824; this number increased to 230 by 1834 and to 450 in 1842. [135]

Yet river travel presented a number of obstacles. Low water during the summer and ice during winter often closed the river to navigation. Shipping routes were forced to follow existing waterways, leaving many areas beyond reach. Unpredictable weather, storms, and obstructions in the river, including snags and sandbars, led to numerous accidents. Shipment of high-bulk, heavy freight with a comparatively low value, such as coal and lumber, was not economically profitable. Finally, the primitive steamboat engines often exploded. In Indiana, these problems were fitfully addressed by the State legislature. In 1820, construction of mill dams on navigable rivers was prohibited to preserve the stream flow. In 1827, a safety inspection of steamboats was passed, but enforcement proved lax. The Federal government also initiated efforts to remove river obstructions and improve navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. [136] Many of the problems with river travel proved intractable, and as swelling populations sparked settlement away from navigable rivers, improvements in overland travel became increasingly essential.

ROADS

Construction and Maintenance

In the early nineteenth century, most roads were simple dirt tracks maintained on an irregular basis at the county or township level. Local statutes often permitted property owners to "work off" their road tax by spending a few days per year helping with maintenance. The road surface was smoothed using hand-held rakes or horse-drawn scrapers. Deep ruts and holes were usually filled with saplings or cut logs and then covered with a layer of dirt. [137] The haphazard character of the maintenance, the essentially unstable quality of the building material, and changing weather conditions generally assured that dirt roads of this type were in very poor condition, if passable at all.

In an effort to address the shortcomings of dirt roads, several other road building technologies were employed. During the early to mid-1800s, timber plank roads enjoyed a popularity far out of proportion to their durability and cost. This paving was created by laying milled wood planks over longitudinal stringers compressed into a sand ballast, creating a wood roadway flush with the ground. Most plank roads had only one lane, albeit with wide earthen shoulders that could be used for passing. Turnpike companies, which charged users a toll, were responsible for construction of many plank roads. The paving originally was touted as lasting seven to twelve years, which would have allowed turnpike companies to recoup construction costs through tolls. In fact, plank roads generally lasted scarcely three years, and their unexpectedly high maintenance costs bankrupted many turnpike companies. [138]

Gravel proved a highly effective road surface, although construction and maintenance remained labor intensive. Several means of gravel construction were pioneered during the nineteenth century. Developed in 1805, the Telford system called for a foundation of large flat stones topped with layers of smaller, broken pieces. The pressure of passing traffic would compress the stone layers into a firm surface. [139] Perhaps the best known graveling technique is macadam, named for its inventor, John Loudon McAdam (or Macadam). With a macadam road, the roadbed began with a twelve-to-fifteen foot wide trough cut slightly below grade and compacted. Three layers of broken stone gravel were laid into the trough. The first layer was about four inches thick and comprised of stone pieces between two and two-and-one-half inches in size. The middle four-inch course was made of stone broken into pieces between three-quarters of an inch and two inches in size. The top two-inch layer featured rock varying in size from sand to three-quarter inches. Each layer was compacted before the next layer was applied. The dust created from breaking the stone was applied last, and then the top layer was regraded to create a crowned roadbed with slight berms and ditches flanking the road for drainage. A final rolling was undertaken to compact the sand and dust into the gravel, creating a smooth hard surface capable of shedding water. [140] Although gravel surfacing was extremely effective, the laborious process of building such roads meant that they generally were concentrated around larger communities and densely settled areas, such as the moderately prosperous town of Rockport in Spencer County.

|

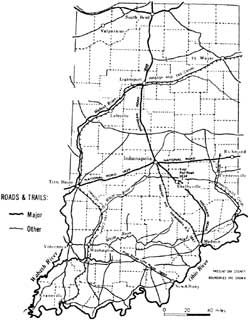

| Figure 16: Early Roads and Trails in Indiana (Madison, 1990: 76) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Consequently, in frontier Indiana during the early nineteenth century, dirt roads predominated. A modest network of overland routes developed by the 1820s, including local roads, stagecoach routes, and turnpikes (Figure 16). Local roads often followed the system of range and township lines used by the county surveyors or paralleled waterways such as Little Pigeon Creek. Tax-supported county roads were not common in Indiana until after State legislation in 1879; before that date most local roads were either informally maintained or private toll roads. [141]

Roads in Southern Indiana

The Vincennes-Troy Road ranked among the earliest roads in southern Indiana. In 1814, a survey was undertaken for the portion of this route that ran from Darlington, the county seat of Warrick County, to Troy, the seat of Perry County. The following year, the Perry County Court authorized construction along an alignment that followed an earlier trail to Polk Patch in Warrick County. The roadway was to be twelve feet wide and sufficiently cleared to allow the passage of carriages. In 1816, this was the road followed by Thomas Lincoln and his family as they traveled to their new homestead in Section 32 of Carter Township in Spencer County. How much the road had been improved by that time is unknown. According to family tradition, the sixteen-mile trip from Troy to the new farmstead was the most difficult part of the Lincolns' migration from Kentucky. Although the Vincennes-Troy Road presumably had been cleared by this date, its unimproved earthen surface was undoubtedly in poor condition. Moreover, the farm site was located four miles west of the road, and the bottomlands in between were filled with dense, almost impenetrable thickets and underbrush. The Lincolns reportedly had to cut their way through the thickets and fell trees with an ax in order to make room for their wagon's passage. [142]

Another early overland route was the Buffalo (or Vincennes) Trace. Originally surveyed in 1805, this route began at the Ohio River near Jeffersonville and continued across the state to Vincennes and the Wabash River. During the early nineteenth century, this roadway was the principal means for crossing southern Indiana and provided settlers with a way to reach Indiana's remote inland areas. Established in 1820, the first stagecoach line in southern Indiana followed the Buffalo Trace. Another road ran from Vincennes south to the Ohio River along the Red Banks Indian trail and extended north to Terre Haute. The Three-Notch Road followed an Indian trail from the Falls of the Ohio to Indianapolis. It was joined at the East Fork of the White River by Berry's Trace, which led to settlements in southeastern Indiana. [143]

Statehood brought increased government interest in road construction. The Enabling Act of 1816 allowed the allocation of 3 percent of proceeds from the sale of government lands within Indiana to be used for transportation improvements. In 1821, the State Legislature appropriated funds for the construction of 24 state roads, with the majority of these radiating from the new state capital at Indianapolis. The legislation's intent was to develop a road system that would reach all areas of the state. Unfortunately, primitive road building technologies and high costs meant that the designated roads were poorly constructed and maintained. Many were little more than partially cleared trails with numerous stumps. The road from Vincennes to Indianapolis, for example, was laid out by dragging a log behind an ox team through the woods, prairies, and marshes that comprised the route. During rainy spring and fall weather, the roads became quagmires that challenged the most daring traveler. [144]

Beginning in 1826, the State government also undertook construction of the Michigan Road, which was intended to connect Lake Michigan to the Ohio River at Madison, by way of Indianapolis. Construction of the federally funded National Road through Indiana began at around this same time. The project's goal was to provide an east-west corridor from Maryland to the western frontier. Construction began as early as 1806 in Maryland, but proceeded at a slow and fitful pace for the next two decades. The road crossed Indiana through Richmond, Indianapolis, and Terre Haute, and ultimately terminated in Vandalia, Illinois. West of Indianapolis, however, the National Road was never fully improved by the Federal government and this segment reverted to state control in 1839. Despite this shortcoming, the road created an important link for the small Indiana towns along its route, and served as the main overland route to and from the East. Both the Michigan and National roads also facilitated settlement of Indiana's interior beyond those areas accessible by waterway. [145]

As the frontier receded and southern Indiana became more densely populated, the need for improved transportation became increasingly critical. Expensive improvements also became feasible for the first time, as the population base was sufficient to support such projects. In Spencer County, the Rockport & Gentryville Plank Road Company was established in November 1850. This organization sprang from the demand for rapid transportation from the farms in the northern half of the county to shipping points along the Ohio River. The road extended a distance of 17 miles, operating as a toll road for seven years, before it fell victim to the falling revenues and high maintenance expenses that typically forced such companies to cease operations. [146]

AGRICULTURAL HISTORY

SIGNIFICANT FACTORS IN LAND SETTLEMENT

As previously noted, the Upland South origins of many of southern Indiana's first settlers profoundly shaped the cultural and social development of the region. Typically of English and Scots-Irish origin, most were either yeoman farmers who raised livestock and farmed their own land, or they aspired to that level of independence. They arrived with the expectation of acquiring secure title to land and even a measure of material wealth, at least as far as could be measured by the ability to hold title to one's own homestead. [147] The knowledge that a clear title was guaranteed in Indiana, as a result of the federal land system, was of particular importance to many settlers, such as Thomas Lincoln, who had lost their holdings as a result of competing land claims and the confusion brought on by the Virginia survey system. Ruinous speculation and litigation proliferated in Kentucky, where overlapping claims made it almost impossible to establish proper ownership. Legislative attempts to resolve the problems generally favored the powerful upper classes and left many homesteaders dispossessed of land they had cleared and tilled, sometimes for years. Furthermore, slavery spread rapidly in Kentucky during the late eighteenth century, partly due to repeated confirmation by the State courts and legislature of the institution's legality. Many settlers who came to Indiana held antislavery sentiments, although these opinions were primarily rooted in fear that bonded labor would diminish the ability of freemen to support themselves and their families. [148]

Just as the political and legal systems of Kentucky failed to promote a democratic distribution of land ownership and free labor competition, the Federal, territorial, and State governments assured the opposite in Indiana. While a few pockets of slavery existed in Indiana from the 1780s through the late 1820s, no government legislation recognized the legality of the institution. As a result, slavery was unlikely to spread north of the Ohio River and pose a threat to the livelihoods of small landholders. Equally important was the knowledge that Federal surveys ensured that land purchased in Indiana came with a clear title, a fact that may have contributed to the relatively low number of squatters in Indiana, even during the frontier period. Finally, legislation such as the Land Acts of 1800 and 1820 created systems for more equitable distribution of land than existed in Kentucky or elsewhere in the Upland South.

Following the end of the War of 1812, thousands of Kentuckians crossed the Ohio River to settle in southern Indiana. As one of the southernmost counties in Indiana, Spencer County was quickly settled, with many townships entirely bought up by the 1820s. The majority of the county's settlers exhibited the previously noted preference for settling first on the Knobs and along the margins of forests. Such a landscape was familiar to Kentuckians and also offered strategic advantages. The nearby forests provided a ready supply of fuel and building materials, while numerous springs offered a convenient water source. A variety of game filled the forests, providing an important supplement to settlers' diets, and hogs could be left to range freely through the woods . The unglaciated soil of the Knobs was more easily tilled, than the prairies, where sodbreaking proved an arduous task that required heavy plows and oxen beyond the financial means of many settlers. Finally, the Knobs were removed from the wetter bottomlands, which were generally considered to be breeding grounds for malaria, and the poorly drained soil was believed to be of a lesser quality than that of the uplands. [149]

Land quality was of critical importance to Indiana's first settlers, as farming was their primary occupation throughout the early to mid-nineteenth century. Other economic endeavors in southern Indiana during this period, such as milling, distilling, tanning, and salt making, largely entailed the processing of agricultural products. Indeed, in 1816, the only factories in Indiana were grist or sawmills. This included Uriah Lamar's small gristmill on Big Sandy Creek, George Taylor's mill in Warrick County, Whittinghill's gristmill in Jackson Township, and Captain Finch's sawmill at Grandview in Spencer County. A limited range of additional commercial activity, including store- and inn-keeping, blacksmithing, quarrying, and iron production, also existed, but the majority of the states' residents lived in rural areas and practiced agriculture. [150] From circa 1800 to 1830, farmers in southern Indiana generally engaged in subsistence farming, but the combination of a favorable climate and rich soils within the study area made small family farms economically viable from an early date. [151]

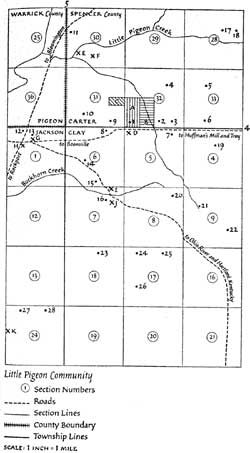

Settlement in Spencer County began during the early 1800s, but proceeded most rapidly between 1816 and 1820. Often, members from one or two families or groups of settlers from the same region migrated together. This pattern is evident in the Little Pigeon Community where the Lincolns settled (Figure 17). The Grigsby, Carter, Gentry, and Wright families had extensive relations in the area and intermarriage was common; Sarah Lincoln, older sister of Abraham, married Aaron Grigsby. On that basis, Spencer County's agricultural community established close-knit relationships strengthened by cooperative efforts to accomplish the large amounts of work necessary to make the land ready for farming. The farm household acted as the center of production, with everyone working together to provide for the family. Many of these close-knit relationships were established before the family moved north. [152]

HOMESTEADING

No matter where the family settled, their first task focused on establishing a temporary shelter, which often was nothing more than an open-faced camp or lean-to that served as the family's home for the first year. This type of shelter was built because it was much easier and less time consuming to construct than a full-scale dwelling. Constructed of a pair of forked trees that supported a cross-beam, the shelter did not require hewing of logs or measuring. Large logs placed onto the frame served as walls and a sapling roof was added. The walls were daubed with clay, mud, and brush for insulation. Animal skins, along with a large hearth, provided interior warmth. [153]

This rude shelter normally was replaced within a year by the family's first permanent dwelling. Built of log, a typical house was usually one story in height, with one or two rooms, and measured approximately 10 feet by 16 to 20 feet. A farmer and his neighbors would raise the hand-hewn and notched logs. The cracks between the logs were chinked with wedges of wood and rocks, and then plastered with mud or clay. Windows and doors were frame and normally planked wood. Greased paper or animal skins served as windowpanes until glass became available. Within these modest structures, family members often slept, cooked, ate, worked, and entertained in the same room. There is evidence to suggest that privies were also included on most pioneer farmsteads. With regard to other ancillary structures, fences typically ranked high among the pioneer's priorities, as they kept animals out of vulnerable cultivated fields and indicated the perimeter of a farm's holdings. Frontier farmers built few outbuildings, although these became more commonplace by the 1830s. Among the first outbuildings constructed were a smokehouse and/or meathouse. Both buildings were used to shelter the meat curing process, a process essential to the frontier family. In later years, crop storage facilities and animal housing were added, including corncribs, granaries, stables, and chicken houses. [154]

Taking precedence even over construction of a dwelling, however, was the task of clearing the land. Settlers viewed this as their most laborious task since it was both time-consuming and backbreaking labor. Trees were cut down or girdled by removing the bark and cambium to kill the tree. Downed trees were rolled into piles and burned. Many times, brush was piled at the base of large trees and set ablaze. This burning of excess timber and brush was said to create a permanent smoky haze over the territory. [155]

After clearing the forest, farmers undertook the arduous task of manually breaking the land for cultivation. Typically, the plows used did not till the land deeply, which tended to encourage soil exhaustion after a few growing cycles. Early plows were made of wood and wrought iron and had a 10-foot beam. A farmer or carpenter hewed the moldboard from a tree, then iron was added, along with old horseshoes. The point of the plow was often made of metal and had to be sharpened frequently. By 1820, numerous patents for improved plow designs had been issued, but most farmers continued to use a traditional plow or plain shovel. [156]

Once the field was plowed, the first crop was sown. Corn usually was the first crop planted, for it provided the maximum amount of food per acre and could be used to feed hogs or distilled into whiskey. Corn also grew well in rich soil with high levels of phosphate, a byproduct of the burning of trees. Corn and pork served as the principal staples for the frontier family's diet. Pioneer women prepared corn for consumption as mush, johnnycakes, corn pone, and hominy. Raising hogs was a relatively simple task, with the animals left to forage freely in the nearby forests. They were rounded up in the fall and penned for a few weeks, during which time they were fed surplus corn in order to fatten them prior to butchering. Virtually all of the hog carcass was used. The meat was seasoned or cured to make sausage, headcheese, pickled pork, hams, and bacon. The intestines provided sausage casings, while the fat renderings were used in making soap. Even the bladder could be turned into a ball for children's play. What little remained of butchered hogs ultimately was fed to chickens. [157]

As frontier farms became more established and surplus products proliferated, the Ohio River provided a critical means of transporting these goods to distant markets. Animal and agricultural products, timber, furs, and hides were shipped via flatboat or steamboat to the Mississippi River and eventually to the Gulf Coast. In a typical year, flatboats carried a quarter-million bushels of corn, 100,000 barrels of pork, 10,000 hams, and 2,500 head of cattle down the Ohio River to New Orleans, which was the leading market center for the West. Auxiliary industries related to export, such as boat building and pork packing, also proliferated in many riverside communities. The proximity of the Ohio River and access to these distant markets meant that Indiana was not an isolated frontier area, but rather an active participant in the national economy. A "triangular trade" pattern developed, in which Midwestern agricultural products were shipped to Gulf Coast market centers, where merchants used their profits to acquire and ship essential commodities, such as cotton, or highly valued products, such as sugar, to East Coast cities. Eastern factories, in turn, produced manufactured goods that reached Midwestern markets by floating down the Ohio River. Farmers used the cash income they received from selling their surplus products in Gulf Coast markets to acquire these manufactured goods. Although somewhat crude, given the transportation technology that was available during the 1810s and 1820s, this trade pattern represented an important stage in the development of a national economy that bound together all the regions of the United States into an interdependent entity. [158]

Surplus agricultural products allowed frontier farmers to purchase manufactured goods, such as stoves, shoes, and woven cloth, as well as luxury items like coffee and sugar, but for their daily foodstuffs, the family typically remained a self-supporting unit. The forests provided ample game, while fruit-bearing trees and vines were cultivated. Some farmers kept honeybees as well. [159] Women tended a "kitchen garden" that included beans, potatoes, onions, and squash. Many of the vegetables were harvested for out-of-season use. Beans, peppers and strips of pumpkin could be dried, while jellies and preserves commonly included pickled cucumbers and kraut. Root vegetables, such as potatoes and carrots, were buried in either a root cellar or a simple hole in the ground near the house. Such produce helped to diversify the frontier diet, which was based primarily on corn and pork. Additional domestic activities including churning butter and making cheese. These latter chores, along with soap making, weaving cloth, and raising poultry were important elements of the "domestic economy." Although such duties were viewed primarily as tasks to be performed by the females of a family, the cooperative character of the farm was driven by profit and all family members could be expected to help. The arrangement worked in the reverse as well, with women often performing chores, such as plowing fields and harvesting crops, that were customarily the provenience of men. [160]

SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Agricultural societies in Indiana were established as early as 1809, with the first on record organized in Vincennes. These societies promoted progressive farming practices and reforms that emphasized technological innovations and sought to make businessmen of farmers. In 1835, Indiana, by act of the State legislature, provided for the organization of county societies and created a state board of agriculture. This was followed by the organization of the Indiana Horticultural Society in 1840. Annual state fairs were first organized during this period. All these organizations promoted the creation of an organized, record-keeping, profit-making farm that did not rely on a single cash crop, but grew diverse products using the latest technologies to promote higher yields while conserving the soil. Many of these organizations published farm journals and agricultural articles. Although their influence between 1800 and 1850 on the typical farmer in southern Indiana is unknown, progressive farming practices became commonplace by the second half of the nineteenth century. [161]

Another significant institution in frontier Indiana was the church. A wide range of denominations were active in southern Indiana, with the most common being Methodist and Baptist. Churches often were the first organized presence in a newly settled area. For example, the Pigeon Baptist Church was founded in 1816, only a couple of years after the pace of settlement in northern Spencer County began to increase. The Pigeon Baptist Church was similar to other churches in the region, since it reflected the shared values and beliefs of the community and gave individuals a place to meet and socialize. The first church meetings were held in individual homes until a church building could be erected. The construction of a church normally occurred within the first five years of its founding and all the land, materials, and labor were donated by its members. The Pigeon Baptist Church was constructed in 1820 and was originally called the "Little Pigeon Meeting House." From the name, it may be inferred that the building was conceived for multiple purposes, including functioning as a school and community center. The church itself served multiple roles, including educating youth, promoting social order, and uplifting the morals of local residents. [162]

As the frontier society stabilized, and population increased, additional institutions were introduced, including schools. During the early frontier period, many children were home-schooled by their mothers and the family typically possessed only one or two books, including a Bible and perhaps a volume such as Pilgrim's Progress. Sunday schools were introduced in Indiana during the 1810s, and by 1829, there were 100 such schools in the state. The schools emphasized religious instruction, including Bible verses, hymns, and moral principles, but they also taught spelling and reading, and many times provided children with their only opportunity to read a book other than the family Bible. Other informal schools also were established. Parents usually paid a small subscription fee of around $1.50 to $2.00 per pupil to finance the exceedingly modest salary that teachers earned. The school calendar often was limited to only two or three months, and teachers seldom were available in remote school districts more than once every two years. Children could attend the schools only in seasons when they could be spared from work on the family farm. [163]

Indiana's 1816 state constitution called for the establishment of a public school system, but a statewide system was not introduced until after 1850. As the countryside became more densely settled, however, county governments began to make provisions for the establishment of a school system financed through public land sales, thereby following the principles that first had been set forth in the original Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Parents often still had to pay subscription fees to finance the educational system as no state or local tax was levied to support schools, but modest one-room schoolhouses began to spring up alongside dusty country roads and a more regular calendar was kept. Children learned by rote to read, write, spell, and cipher to the rule of three, which provided them with at least a rudimentary set of intellectual skills. No system existed for certifying teachers and their level or education and dedication varied widely, but most parents believed it to be sufficient if teachers conveyed to children the ability to read and write and perform simple arithmetic. Attempts to establish more advanced educational levels met with public resistance well into the mid-nineteenth century, particularly in southern Indiana. Many people believed education to be a luxury that should not be indulged until improvements such as roads, canals, and railroads had been provided. Others opposed the introduction of taxes, or believed that education beyond a basic level simply was not necessary to everyday life in the West, or were wary of any attempt to establish a centralized system that would erode local control and, ultimately, individual liberty. As a result, the schools that were available in southern Indiana in the early decades of the nineteenth century typically were a haphazard collection with irregular calendars, teachers of uncertain merit, and pupils who attended only when weather, chores, and family means to pay tuition did not interfere. [164]

While the public resisted establishment of a formal school system, there is evidence of strong support to other educational institutions, such as libraries, despite the fact that books were very expensive. In Spencer County, an 1831 law set aside 10 percent of the proceeds from the sale of town lots for the purpose of founding and maintaining a county library. The same year, several books were purchased for the library, including a theological dictionary, collections of sermons and meditations, monographs on ancient history and geography, and a few literary works such as Shakespeare's plays and Byron's works. By 1855, Spencer County could boast six small libraries with a combined collection of 300 volumes. [165]

In a matter of only a few decades, Spencer County's settlers transformed the landscape from a nearly trackless wilderness to a prosperous agricultural community. With easy access to waterways and gradually improving roads, local farmers participated in the national market economy from an early date, moving from subsistence to commercial farming with rapidity. Commercial success allowed the continuation of social and cultural development, as evidenced by the presence of agricultural societies, churches, and libraries. It was within this rapidly evolving environment that the Lincoln family established their homestead in 1816.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/hrs/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003