|

LONGFELLOW

Papers Presented at the Longfellow Commemorative Conference April 1-3, 1982 |

|

"STANDING ON THE GREEN SWARD: THE VEILED CORRESPONDENCE OF NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE AND HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW

By Rita K. Gollin

A graduate of Queens College, New York, and the University of Minnesota, Dr. Gollin is Professor of English at the State University of New York at Geneseo and President of the Nathaniel Hawthorne Society. Her most recent publications include Nathaniel Hawthorne and The Truth of Dreams, as well as "The Hawthornes' Golden Dora," and "The Mathew Brady Photographs of Nathaniel Hawthorne," both published in 1981 in Studies in the American Renaissance.

Has the reader gone wandering, hand in hand with me, through the inner passages of my being, and have we groped together into all its chambers, and examined their treasures or their rubbish? Not so. We have been standing on the green sward, but just within the cavern's mouth, where the common sunshine is free to penetrate, and where every footstep is therefore free to come. I have appealed to no sentiment or sensibilities save such as are diffused among us all. So far as I am a man of really individual attributes, I veil my face.

(Mosses from an Old Manse, pp. 32-33)A veil may be needful, but never a mask.

(American Notebooks, p. 23)

If we try to define Hawthorne's relationship to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the short form is that they were classmates at Bowdoin; that twelve years later Hawthorne sent Longfellow a copy of Twice-told Tales, his first published book, whereupon Longfellow published an enthusiastic review of it; and that from then on they were warm friends who exchanged dozens of letters, dined together, counselled together, and congratulated each other on their publications. But this does not take into account the complexities of Hawthorne's self-presentations—neither the self protective strategies of his requests, nor the many ways Hawthorne used Longfellow both as a yardstick and sounding board for his own professional ambitions. Even when Hawthorne's letters sound most relaxed and least ironic, when he rejoiced in his friend's latest literary triumphs, they hint at anxieties about his own role as writer and even question the value of reputation.

One way of coming to terms with the relationship that lasted more than forty years is to look at several points of professional juncture crucial to Hawthorne's career—the first centering on Twice-told Tales in 1837, the second on a projected collaboration between the two men a year later, and a third on Longfellow's publication of Evangeline in 1847. We must examine these junctures, but also determine what preceded and followed them.

On the seventh of March, 1837, the day after his first volume of short stories was published, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a brief and relatively formal note to a Bowdoin classmate who had already won literary acclaim. "Dear Sir," he began, "The agent of the American Stationers Company will send you a copy of a book entitled 'Twice-told Tales' of which, as a classmate, I venture to request your acceptance." With this request went another unstated one: Hawthorne hoped Longfellow, a Harvard Professor and author of language textbooks and the well-received travel sketches, Outre-Mer, might publicly praise the collection of tales and thus advance the career of its author. The tone of the note is humble and even apologetic. "We were not, it is true, so well acquainted at college, that I can plead an absolute right to inflict my 'twice-told' tediousness upon you," Hawthorne said, but immediately modified the apology to plead a relative if not an absolute right: "I have often regretted that we were not better known to each other, and have been glad of your success in literature, and in more important matters." Then he implicitly withdrew his concern about inflicting "tediousness" by stating that the tales had not only won publication before but seemed "worth offering to the public a second time." Hawthorne concluded gracefully with the hope that the tales would repay "some part of the pleasure which I have derived from your own Outre Mer" (under the guise of courteous modesty ranking his first book with Longfellow's), then signing himself "Your obedient servant."

In this letter, Hawthorne was at once courting Longfellow and asserting himself as an equal, trying to advance his career despite a modicum of anxiety about the merits of his case. And with the letter Hawthorne initiated a relationship that would serve him well in establishing and defining himself as a man of letters. In the thirty or more letters addressed to Longfellow in the course of the next twenty-seven years, Hawthorne often presented himself with self-denigration, whether ruefully or whimsically, even when little seemed at issue beyond an invitation to dinner. Particularly at the beginning of the correspondence, Hawthorne approached as a petitioner, directly or indirectly soliciting practical assistance, veiling his deep concerns or surrounding them with ironic disclaimers. This is not to say that Hawthorne was a hypocrite; but in writing to Longfellow he adopted personae calculated to flatter the receiver and advance his career while protecting himself from embarrassment. Truth is laced with whimsy or projected with artful fantasy in these letters just as in the prefaces Hawthorne addressed to readers of his books: he presented himself honestly as a man of letters intent on pursuing an "intercourse with the world," yet determined to keep his "inmost me" concealed.

"Has the reader gone wandering, hand in hand with me, through the inner passages of my being," Hawthorne asked in the preface to Mosses from an Old Manse, "and have we groped together into all its chambers, and examined their treasures or their rubbish?" The answer is immediate and unequivocal. "Not so. We have been standing on the green sward, but just within the cavern's mouth, where the common sunshine is free to penetrate, and where every footstep is therefore free to come." [2] Hawthorne's correspondence with Longfellow takes the same position. "So far as I am really a man of individual attributes, I veil my face," Hawthorne said in the Mosses; and the veil is firmly in place in the letters to Longfellow. It must be said that Longfellow was evidently satisfied by this relationship content to stand on the green sward without trying to penetrate the cavern. The two writers played roles with one another, but without dissembling. Hawthorne once commented in his notebook, "A veil might be needful, but never a mask"; [3] and delicately but deliberately, he offered Longfellow moments of privileged insight. Even in his last letter to his old friend, in January 1864, after praising the newly published Tales of a Wayside Inn, he confessed his fear that his own career was nearly over, though he might yet write one last best book. Then he concluded poignantly, though with a characteristic note of mild flattery, "You can tell, far better than I, whether there is ever anything worth having in literary reputation, and whether the best achievements seem to have any substance after they grow cold."

At Bowdoin, as Hawthorne later recalled, "no two men could have been more unlike." The future poet and professor "was a tremendous student, and always carefully dressed, while he himself was extremely careless of his appearance, no student at all, and entirely incapable at that period of appreciating Longfellow." [4] The outlines of the contrast are valid. The two young men graduated together in 1825, members of a class that numbered only 38. They had worked under the same professors and satisfied the same requirements. But differences of age and (more important) of temperament explain their relative indifference to one another as undergraduates. Longfellow was only fifteen when he and his older brother Stephen entered Bowdoin as sophomores: he was a serious and well-disciplined young man, never tempted by such distractions as card-playing or wine-drinking. Predictably, he joined the more scholarly and politically conservative of Bowdoin's two literary societies, the Peucinian. Aiming at a distinguished literary career, he published poems and essays in such well-known periodicals as the American Monthly Magazine; and at his classmates' request he composed a poem for their final social meeting. Graduating fourth in his class, Longfellow was elected to the just-formed chapter of Phi Beta Kappa; and even more gratifying, he was appointed to Bowdoin's new chair of modern languages, a position he would assume after studying languages abroad. [5] Professors and classmates could have made good guesses about the professional distinction Longfellow would achieve; but only an acute professor or an intimate friend could have predicted Hawthorne's.

At Bowdoin, Hawthorne was remembered as a reserved and independent young man who nonetheless made close friends and joined several social clubs as well as the Athenean literary society. It is clear that he had a low tolerance for regulations, amassing fines for such infractions as missing religious services and playing cards. Nevertheless, his essays and Latin translations were admired and his class rank of eighteen was respectable. But he was relieved to learn that because of what he called "neglect of Declamation," he would not be permitted to deliver a commencement address. Although he bragged to his sister Louisa about his "splendid appearance" on the only occasion when he declaimed in Chapel—speaking in Latin as did only one other of the fifteen participants, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—public speaking was always a burden for him. [6] He would court public approval in a more solitary manner. But perhaps only his friend Horatio Bridge could have guessed that he would leave Bowdoin to write stories in Salem for what he would call his "twelve lonely years," or that he would later establish a remarkable career as a writer of fiction.

To the casual observer, Longfellow, the successful scholar graduating at eighteen, had little in common with the intractable if somewhat irresolute twenty-two year old Hawthorne. Regarded with the clarity of hindsight, by 1825 both had defined professional paths they would follow throughout their lives—Longfellow's straight, Hawthorne's meandering. Yet when Longfellow gave his commencement address predicting that "palms are to be won by our native writers," he adumbrated the direction of Hawthorne's career as well as his own, and established a base line for their mature friendship.

Although from a pragmatic perspective, Hawthorne's first letter to Longfellow is the most important, an invitation to the dance expressed with deferential assertiveness, his second letter is most artful (as well as the longest) and indirectly the most confessional. The letter that provoked it has not survived, but Hawthorne's response establishes that Longfellow had written a "kind and cordial" reply, expressing interest in Hawthorne's "situation", and referring to "troubles and changes" of his own (presumably the death of his wife and his new teaching position at Harvard). Reluctant "to burthen you with my correspondence," Hawthorne waited nearly two months before proffering his concerted effort at self-assessment.

Then, protesting that "your quotation from Jean Paul, about the 'lark-nest', makes me smile," he compared himself to a more dismal bird: "like the owl, I seldom venture abroad till after dusk," he said. The rest of the long first paragraph is a complaint about how lonely and insubstantial his life had been since they last met. At first he disavowed responsibility for his predicament: "By some witchcraft or other—for I really cannot assign any reasonable why and wherefore—I have been carried apart from the main current of life, and find it impossible to get back again." But then putting aside the notion of wholly innocent victimization, Hawthorne accepted blame for at least initiating his problem: "I have secluded myself from society; and yet I never meant any such thing, nor dreamed what sort of life I was going to lead. I have made a captive of myself and put me into a dungeon; and now I cannot find the key to let myself out—and if the door were open, I should be almost afraid to come out." He almost completely devalued himself and his past ten years: "I have not lived, but only dreamed about living"; the few pleasures of his dream life were neither substantial nor enduring.

The next paragraph continues the ambivalent self-denigration. Longfellow supposed he was studious, but he had merely "turned over a good many books"; and he made light of his writings without impugning them: "I do not think much of them—neither is it worth while to be ashamed of them." They would have been better if he had been more deeply involved in the real world; but the public was at least partly to blame because he never had "warmth of approbation, so that I have always written with benumbed fingers." Nonetheless he claimed credit for managing to capture glimpses of the real world in a few writings which "please me better than the others."

The first two paragraphs have received a lot of critical attention, and rightly so. They present in the fullest form Hawthorne's own self-dramatization as an idle dreamer deprived of the real existence that fiction requires (a dramatization that would recur in the courtship letters to Sophia and that turns up in the Oberon sketches as well as in the dedication of the Snow Image), intermixing self-pity, self-mockery, and self-exoneration.

But the next three paragraphs are also interesting and important, and furthermore almost devoid of self-pity. Here as in the first letter to Longfellow, Hawthorne presented himself not as a fragile isolato but as a practical man of letters. He announced himself committed to "scribble for a living," and willing to take on the drudgery of editing or of writing children's books. Then he responded to Longfellow's praise with a four step minuet: he was pleased that Longfellow had previously read and admired some of the stories; he felt inclined to discount this praise since "you could not well help flattering me a little"; but on the other hand he valued Longfellow's "praise too highly not to have faith in its sincerity"; and finally, the book was selling "pretty well."

Then, in the last paragraph, Hawthorne surrendered, if temporarily, the role of owl: he planned a summer excursion "somewhere in New England," which would make him feel "as young as I did ten years ago." In the last two sentences, self-effacement is once again followed by self-assertion. "What a letter am I inflicting on you!" he said, undercutting the entire bravura performance; but he ended confidently, "I trust you will answer it."

The third and last letter of this springtime exchange with Longfellow is as short as the first but wholly different in tone. Hawthorne wrote it two weeks later, immediately after reading with "huge delight" Longfellow's long and laudatory review of Twice-told Tales for the influential North American Review. [7] "I frankly own that I was not without hopes that you would do this kind office for the book," he admitted, "though I could not have anticipated how very kindly it would be done." There is no trace of the imagery of witchcraft or dreamland in his jocular assertion that "there are at least five persons who think you the most sagacious critic on earth—viz, my mother and two sisters, my old maiden aunt, and finally, the sturdiest believer of the whole five, my own self." Here the new persona is that of a brashly confident "scribbler," determined to doubt only "those who censure me," and to hold a talk" with his kind critic. The first letter had been a plea for help, the second a plea for sympathy, and the third an anticipation of friendship.

Longfellow's generous review is the key to the change, designed to unlock Hawthorne's dungeon and make him willing to come out. In response to his classmate's overture, Longfellow enthusiastically introduced him to readers of the most influential Whig journal as a major new American writer. Downplaying the dark strains in the narratives, Longfellow stressed Hawthorne's bright vitality.

The tone is established at the start by the lofty image of Hawthorne as a "new star in the heavens." In a mild burst of humor, Longfellow anticipated that other "star-gazers" would merely report on the new star's magnitude and assign it a constellation; but what he proceeded to offer is unstinted praise for this "sweet, sweet book" which "has the freshness of morning and of May." It is easy to dismiss Longfellow's diction and imagery as conventional, and it is true that his conception of Hawthorne's heart as peaceful and gentle is simplistic. Yet he was astute enough to recognize "deep waters" in Hawthorne's inner life, saying that "to him external form is but the representation of inner being," and warning readers that they could envisage on the "calm, thoughtful face" of the writer an occasional "strange and painful expression." But he did not otherwise prepare them for the blackness of such tales as "The Wedding Knell," "The Minister's Black Veil," or "The Hollow of the Three Hills," nor for the skeptical irony of "The Haunted Mind" or "The Gentle Boy." He presented Hawthorne to the genteel readers of The North American Review in terms they would value—as a "man of genius," a loving poet, a friendly man with a "pleasant philosophy" and "quiet humor" who feels "a universal sympathy with Nature, both in the material world and the soul of man," one who "has wisely chosen his themes among the traditions of New England," and whose style is "as clear as running water." As a typical mid-century reviewer, Longfellow devoted most of his space to quotations, predictably from such accessible sketches as "A Rill from the Town Pump." Then, gracefully identifying himself as one of many admirers, he concluded, "Like children we say, 'Tell us more.'"

Fourteen years later, near the end of his preface to a new edition of Twice-told Tales, Hawthorne spoke of the "kindly feeling" of the book's first readers who regarded him "as a mild, shy, gentle, melancholic, and not very forcible man." He might have recalled Longfellow's review when he wrote that, and when he said some of his later writings might be construed as efforts "to fill up so amiable an outline." Certainly his self-definition was in part determined by what he saw mirrored in Longfellow's response. In 1837, Twice-told Tales had led "to the formation of imperishable friendships," he said; and Longfellow's wide-eyed pastoral enthusiasm helped define the terrain of their ongoing relationship. [8]

A year after the first letter to Longfellow, Hawthorne requested a different kind of professional assistance. His letter of 21 March 1838 centers on a project they had already discussed: collaborating on a collection of children's stories. Hawthorne's eagerness for the venture is evident beneath his equable and even business-like tone. He began with regret that Longfellow had "not come to dinner on Sunday" and ended with an intention to visit him soon; but the bulk of the letter urges the collaboration. Hawthorne mentioned his other literary projects and responsibilities only to urge that this one "need not impede any other labors." He referred to "your" book and invited Longfellow to shape out "your" plan, saying "you shall be the Editor, and I will figure merely as contributor," since "the conception and system of the work will be yours." But beneath this veil of deference, Hawthorne presented himself in the posture of an equal. He suggested that the stories be connected by a narrative thread (as he would later connect his own children's books); he suggested that they all be "either original or translated—at least, for the first volume"; and he even had a particular length in mind—two to three hundred pages of large print. Aware that he had more to gain than Longfellow, he temptingly predicted a new kind of fame: they would "twine for ourselves a wreath of tender shoots and dewy buds" at the same time that they would "perchance put money in our purses." He even offered to "get our baby-house ready by October."

Longfellow did visit Hawthorne in "dull, Sunday-looking Salem" on the following Sunday, and discussed "literary matters" with him. Although a hint of condescension is detectable in the journal entry—"he is much of a lion here, fed, and expected to roar"—Longfellow believed Hawthorne was "a man of genius and fine imagination" who was "destined to fly high." [9] But if the collaboration was discussed, Longfellow did not think it worth recording.

Seven months later, in a letter of 12 October 1838, Hawthorne breezily yet earnestly raised the topic once more. He began by complaining "It is a dreadful long while since we have collogued together," then said he had enjoyed "rambling about since the middle of July"; but the next few sentences assert his main purpose. "Mean time, how comes on the 'Boy's WONDER-HORN?'" he asked. Then he punningly enlarged the question but self-protectively anticipated disappointment: "Have you blown your blast?—or will it turn out to be a broken-winded concern?" He claimed that he himself had no "breath to spare, just at present," then doubly retracted this objection: "I think it a pity that the echoes should not be awakened," he said, stressing that the venture would require little time or effort. His entire second (and last) paragraph concerns the possibility of Longfellow lecturing at the Salem Lyceum: the local lion Hawthorne promised to "set in motion all the machinery over which I have any control" and "puff-puff-puff-in the newspapers." Clearly, however, he was far less interested in a Lyceum lecture than in a financially profitable joint venture. The letter ends confidently with an unusually peremptory request. "Write forthwith," Hawthorne ordered, then signed, "Truly your friend."

Hawthorne's abrupt shifts of tone and stance might well have confused Longfellow. Shortly after receiving this letter, he told a friend he planned to see Hawthorne the following day; but he does not sound eager. Perhaps recalling Hawthorne's earlier self-definition, Longfellow reflected, "He is a strange owl; a very peculiar individual, with a dash of originality about him very pleasant to behold." [10] The word "behold" does not suggest a prospective collaborator.

Hawthorne had evidently given up hope for the collaboration by the time of his next letter, dated 12 January 1839. At this point Longfellow intended to assemble the children's book alone, though he never did complete it. Somewhat petulantly, Hawthorne said his imminent appointment as Inspector of the Boston Custom House made it "more tolerable that you refuse to let me blow a blast upon the 'Wonder-Horn,'" and he even warned that he might prepare a competing volume. But he downplayed his disappointment. Briefly he assumed a comic persona for his prospective governmental role: he had "as much confidence in my suitableness for it, as Sancho Panza had in his gubernatorial qualifications." That is, Hawthorne professed a robust optimism despite his total inexperience. With unwontedly hearty whimsy, he speculated that as "Port-Admiral," he might write sketches with such titles as "Trials of a Tide-Waiter."

At the same time he had another practical project in mind. If he renounced hope of one form of collaboration, he hinted at another. He knew Longfellow had been thinking of establishing a literary newspaper, but not that the idea was already abandoned. Stressing that he would have a lot of free time when he came to Boston, he offered "whatever aid a Custom-House officer could afford." Somewhat coyly he even suggested a name for the journal: his own title—"The Inspector."

During the next few years while Hawthorne worked joylessly as Custom Inspector, his letters to Longfellow are relatively few, brief, and forthright. He urged a visit from Longfellow; he arranged to buy cigars for him. But concern about his vocation, never far beneath the surface, emerges painfully in his letter of 16 May 1839, which querulously begins, "Why do you never come and see me?" He was worried about publishing a second volume of stories, and more important, about surviving as a writer: "If I write a preface," he said, "it will be to bid farewell to literature; for, as a literary man, my new occupations entirely break me up."

Longfellow did not in fact visit Hawthorne until five months later, but he responded immediately to Hawthorne's implicit request by writing to his New York publisher, Colman, suggesting publication of two volumes of tales by "a great favorite with the public, . . . who is in future to stand very, very high in our literature." Colman was interested, but unfortunately he went bankrupt before anything could come of it. Again Longfellow had failed Hawthorne, though this time not for want of trying. After his long-deferred visit to his friend in October, Longfellow once again heartily praised Hawthorne in his journal (repeating the initial metaphor of his review of Twice-told Tales)—"He is a grand fellow, and is destined to shine as a 'bright particular star' in our literary heavens." [11] Yet evidently he felt no further inclination to give destiny a helping hand.

Hawthorne"s letter two months later clearly establishes that at this time he measured himself as a literary failure in contrast to Longfellow. He earnestly praised Longfellow"s two recent volumes, Hyperion and Voices of the Night: he read them "over and over . . . and they grow upon me at every re-perusal." But because his "heart and brain are troubled and fevered now with ten thousand other matters," he felt unable to write his planned review of them. Even his optimistic protestation, "but soon I will set about it," is undercut by the humility of his closing wish: "God send you many a worthier reviewer!" Characteristically, Hawthorne had even less to say about his state of mind in person: "Hawthorne is a taciturn youth," Longfellow noted on 5 April 1840. "He never speaks except in a tete-a-tete, and then not much." [12]

But the last letters of this period are quite cheerful. Not only was Hawthorne about to end his term as Inspector—"I have broken my chain and escaped from the Custom-House," he announced in October—but he had successfully re-entered the lists as a man of letters. His first children's book, Grandfather's Chair, was nearing publication, and he already had another in mind. His letter of November 20 makes fun of himself as Grandfather, hyperbolically exaggerating his feeling of age, though the mockery is laced with complacency: "By occupying Grandfather's Chair, for a month past, I really believe I have grown an old man prematurely—and not very prematurely either," Hawthorne wrote "My youthful ardor and adventurous spirit have left me, and I love to keep my feet on the hearth, and dread many shapeless perils, when I contemplate such a journey as from here to Cambridge. . . . It is easy to detect a serious note beneath the conceit: for years Hawthorne had worried about his slow professional advancement, worried that he might grow old before he became famous. Thus it was important for him to relinquish the sedentary posture of "aged men." He would soon journey to Cambridge, and he invited Longfellow to visit him in Boston, where he generally walked out between twelve and three, "dining in the interim."

Two years later, Hawthorne had four volumes of children's stories in print, his expanded Twice-told Tales had been praised by Poe as well as Longfellow, and he was at last married to his beloved Sophia. Consequently, his few letters to Longfellow from the Old Manse sound remarkably contented. Indeed, the few requests they make of Longfellow can as easily be interpreted as favors to Longfellow. On 26 November 1842, soon after Longfellow's return from half a year abroad, Hawthorne good-naturedly invited congratulations on his marriage, and entreated a visit: a lecture at the Concord Lyceum would gratify Emerson and the other good people of Concord, including "my wife and me." The following month he wrote apologetically about his delay in answering Longfellow's letter, but almost braggingly explained, "I am very busy with the pen, and hate to ink my fingers more than is necessary." He was diligently producing tales and sketches as well as performing some editing tasks. Deferring the pleasure of dining with Longfellow in Cambridge, he again urged a visit to Concord: to counter the discomforts of Winter, he offered "the glow of felicity" and the sport of early morning ice-skating. He ended with a flattering comment: surprised to hear Longfellow had "poetized a practical subject" in Poems on Slavery, he nevertheless had "faith in their excellence."

Relations were even warmer after Longfellow remarried. He reported his delight with "The Birthmark" and urged "Hawthornius" to visit. Hawthorne did indeed dine at Craigie House and met the new Mrs. Longfellow; but the busy poet never made it to Concord.

Hawthorne's third letter to Longfellow from the Old Manse comes near the end of his three year tenancy, declining to visit Longfellow and his brother Stephen in Cambridge "for various weighty reasons." Cordially he invited Stephen to Concord but ironically commented he would no longer even bother to invite Longfellow himself. Then he hinted at his expectation of an exotic political appointment, warning that he might soon move "beyond the limits convenient for visiting—perhaps as far as Pekin."

Of course, Hawthorne did not go to Peking, but to Salem; and the letters to Longfellow during his term as Surveyor at the Salem Custom House reflect the increased intimacy between them. Apparently at this period (which I have called their third professional juncture), Hawthorne felt a new parity in their relation hip. He had a respected political appointment, the stories he wrote were soon in print, and Mosses from an Old Manse was published and well-reviewed. Hawthorne was often a guest at Craigie House, feeling free to ask if he could bring along a guest of his own, while Longfellow enjoyed playing host. Although a meal with Hawthorne in a Salem hotel gave him no pleasure—"No German village with a dozen houses in it could have furnished so mean a one," he insisted in his journal—at his own table, matters were different. Two weeks after the unpleasant Salem dinner, he wrote in his journal that he was "more and more struck with Hawthorne's manly beauty and strange, original fancies," then noted Hawthorne's opinion that he should resign his professorship and devote "these golden years of life to literature alone." [13] The two men were easy companions, but usually at Longfellow's table and on his terms.

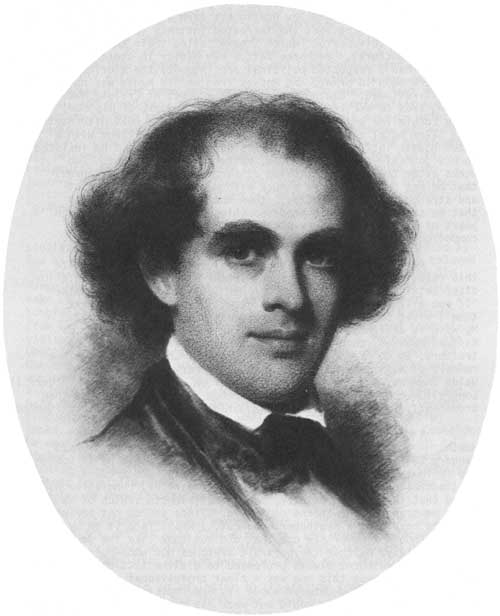

At this time, two episodes involving portraits dramatize this relative intimacy. The first letter Hawthorne sent Longfellow after settling in Salem, on 14 October 1846, ends with a promise: "If you will speak to Mr Johnson, I will call on him the next time I visit Boston, and make arrangements about the portrait. My wife is delighted with the idea," he said. The idea was for Eastman Johnson, then a young artist specializing in crayon portraiture, to do crayon and chalk drawings of Longfellow and close members of his family as well as four literary friends—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sumner, C. C. Felton, and Hawthorne. (Figure 1) Longfellow commissioned and paid for them all, then displayed them prominently in Craigie House. Undoubtedly Hawthorne felt complimented. [14]

|

| Figure 1. Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) by Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) Boston, 1846. Crayon and chalk on tan wove paper. Longfellow NHS Collection. |

A second portrait venture suggests in another way that Hawthorne and Longfellow were publicly regarded as peers. On 23 January 1847, Hawthorne wrote Longfellow that he would be in Boston the following week "and will call on Mr. Martin, and arrange a sitting, either here or there." Four days earlier, Longfellow had noted that the English painter "made a full-length sketch of me for a newspaper." Hawthorne continued, "Since you do not shrink from the hazard of a newspaper wood-cut, I shall face it in my own person, though I never saw one that did not look like the devil." [15] (Unfortunately, neither the portrait sketches nor wood-cuts have surfaced.) Hawthorne always professed to dislike sitting for portraits, but perhaps because this one was a clear professional compliment, he was unusually good-natured about it, and comically wondered what he should wear. He could not wear his dressing-gown to Boston; he had given away the "blue woollen frock" he wore outdoors at Brook Farm and Concord; so he would choose the less formal of his only two options: "in a dress-coat, I should look like a tailor's pattern, . . . so that I think I shall show myself in a common sack, with my stick in one hand and hat in the other."

Right after this overflow of mock-vanity comes a serious comment about Longfellow's work on Evangeline: "I rejoice to hear that the poem is near its completion." Ten months later he wrote of his great pleasure in reading it. Possibly a sense of proprietorship in the subject of the poem contributed to his further feeling of intimacy with Longfellow. The poet had thought of Evangeline as Hawthorne's "generous gift" since 1841, when Horace Conolly had told him about the Acadians at Hawthorne's request; and Longfellow's letter of 29 November 1847 affirms that the success of Evangeline "I owe entirely to you, for being willing to forego the pleasure of writing a prose tale, which many people would have taken for poetry, that I might write a poem which many people take for prose." [16] Hawthorne's letter of November 11 praises Evangeline, predicts it would "prove the most triumphant of all your successes." and mentions his review which would appear two days later in "our democratic paper, which Conolly edits," the Salem Advertiser. The review itself is concise but enthusiastic, using some of the same images and criteria that Longfellow had used for Twice-told Tales over a decade before: it is a "sweet and noble" work "founded on American history" and written "as naturally as the current of a stream." [17]

But at the very moment that he unstintingly praised Evangeline, Hawthorne was wrestling with heavy problems. "How seldom we meet!" he complained: his responsibilities at the Custom House and home left him little leisure; and worse, he found himself unable to write. His letter to Longfellow states the problem: "I am trying to resume my pen; but the influences of my situation and customary associates are so anti-literary, that I know not whether I shall succeed. Whenever I sit alone, or walk alone, I find myself dreaming about stories, as of old; but these forenoons in the Custom House undo all that the afternoons and evenings have done. I should be happier if I could write—also, I should like to add something to my income, which though tolerable, is a tight fit." Then Hawthorne again asked Longfellow for help, more directly than before: "If you can suggest any work of pure literary drudgery I am the very man for it."

Longfellow tried to respond to this last request, but without addressing the deeper problem. Over two months later, thinking "with friendly admiration" of his friend's review of Evangeline, he suggested that Hawthorne might write a history of the Acadians before and after their expulsion, using documents that Felton had located in the state archives. But even though Hawthorne said he was willing to "talk it over," he did not feel the material was in any sense his. [18]

He had felt no compunctions about giving over his claims to the story of Evangeline. What now depressed him was his near paralysis as a writer of fiction. That he requested of Longfellow "some work of pure literary drudgery" is a measure of his new state of despondency.

A year and a half later, his problem was different and worse. He began his letter to Longfellow of 5 June 1849 by praising the newly published Kavanagh, using familiar pastoral imagery: "It is . . . as fragrant as a bunch of flowers, and as simple as one flower . . .—as true as those reflections of the trees and banks that I used to see on the Concord." But "political bloodhounds," he complained, made it impossible for him to write a review for the Democratic Advertiser.

Most of this unusually long letter expresses Hawthorne's furious response to the political vendetta that would soon remove him from office. He assumed the burlesque posture of a blameless victim intent on revenge: he might "immolate one or two" of his enemies, bury the treacherous monster Conolly "in oblivion," but "let fall one little drop of venom" on a worthier adversary to "make him writhe before the grin of the multitude," and pursue others with satire designed to poison even their bedchambers and their graves. Perhaps the fact that his two children had nearly died of scarlet fever intensified his black-humored malice, which would soon color the pages of "The Custom-House." But Hawthorne at once justified and modulated his rage by venturing a more exalted if more generalized self-definition. Without claiming to be a poet, he "cannot but feel that some of the sacredness of that character adheres to me, and ought to be respected in me." He insisted that the vengeance he contemplated was not merely personal but "in your behalf as well as mine," since what was violated is "the sanctity of the priesthood to which we both, in our different degrees, belong." As a writer he too was a holy man, though clearly he believed Longfellow's "degree" was higher.

Three days later he learned of his dismissal; and not long thereafter he wrote Longfellow a brief note that announces his equanimity despite political decapitation. "I feel pretty well since my head has been chopt off," he said wryly. "It is not so essential a part of the human system as a man is apt to think." [19]

The next few years were the great years of Hawthorne's rising fame, the years during which three major novels emerged in rapid succession, as well as new volumes of stories. Predictably, the correspondence with Longfellow is mellow, assuming mutual concern and abiding friendship. Now most of the compliments come from Longfellow. Right after The Scarlet Letter was published he noted in his journal, "a most tragic tragedy. Success to the book!" After reading Melville's anonymous review of Mosses from an Old Manse, he wrote Hawthorne to endorse every comment of the "appreciating and sympathizing critic," and a year later he told Hawthorne of his "intense interest" in The House of Seven Gables. [20] Rarely does Hawthorne even hint at inner problems during this period. He wrote on 8 May 1851 that he felt almost too comfortable in Lenox: "sometimes my soul gets into a ferment . . . and becomes troublous and bubblous with too much peace and rest." The two men were on a relaxed plateau of friendship. They introduced each other to new admirers; Longfellow helped Hawthorne house hunt; then from his new Concord residence, Hawthorne wrote contentedly, "I am beginning to take root here, and feel myself, for the first time in my life, really at home." At the high point of this period of shared contentment, Longfellow gave a dinner to honor Hawthorne, who was about to assume the well-paid and well-respected post of American Consul in Liverpool. "The memory of yesterday sweetens today," Longfellow reported in his journal for 15 July 1853. "It was a delicious farewell to my old friend. He seemed much cheered." [21]

During the years Hawthorne was in Liverpool, they corresponded as cronies, with Hawthorne repeatedly urging Longfellow to come to England to bask in his fame. Hawthorne enjoyed being able to offer Longfellow the privileges of the diplomatic pouch, on one occasion venturing to tease him about a letter addressed to a young woman as "one of your flirtations." [22]

In several letters, Hawthorne examined his ambivalence about his native land, from the dual vantage point of England and established literary reputation. "America is a good land for young people," he told Longfellow, but "I have had enough of progress." Only occasionally did he feel at all homesick. He speculated that "we have so much country that we have really no country at all; and I feel the want of one, every day of my life. This is a sad thing."

It is not surprising that Hawthorne also shared with Longfellow some of his speculations about his future as a man of letters. As he wrote in May 1855, he expected that after leaving the Consulship, his savings would support his family for a few years "with everything but luxuries—and with those, I hope, my pen will not be too blunt or stiff to provide us, for some years yet to come." The year before, he had rejoiced that coming to England relieved him "from the tyranny of public opinion," presumably including opinions about his writings. But his concern went beyond money and reputation. "Don't you think that the autumn may be the golden age both of the intellect and the imagination?" he asked. There is a hint of envy in his praise of Longfellow: "You certainly grow richer and deeper at every step of your advance in life. I shall be glad to think that I, too, may improve—that, for instance, there may be something ruddier, warmer, and more genial, in my latter fruitage." Even more playfully, he said "Ale is an excellent moral nutriment; so is English mutton; and perhaps the effect of both will be visible in my next romance." Perhaps he recalled his letter to Longfellow of June 1837 worrying that his life was so secluded that his writings lacked substance. Now, twenty-eight years later, he still yearned to improve, to produce "ruddier, warmer" fruit.

When the Hawthornes returned to Concord in the summer of 1860, the two writers immediately resumed their affectionate relationship. Hawthorne attended the monthly meetings of the Saturday Club in Boston, contriving to sit next to his old friend, who seemed younger if less well groomed than before. [23] But the following year after his beloved wife died horribly of burns, Longfellow no longer attended club dinners; and Hawthorne told his friend and publisher James T. Fields that he could not "reconcile this calamity to my sense of fitness. One would think that there ought to have been no deep sorrow in the life of a man like him; and now comes this blackest of shadows, which no sunshine hereafter can ever penetrate! I shall be afraid to meet him again. . ." [24] He had thought Longfellow led a charmed life; but that idea was no longer tenable.

Perhaps his new response to Longfellow explains the unwonted solemnity in his letter of 2 January 1864. He expressed his "comfort and delight" in the Tales of a Wayside Inn, undoubtedly pleased that Longfellow mentioned him in the poem and assumed its readers were familiar with "My Kinsman, Major Molineux." But he concentrated on his own admixture of ambition and melancholy resignation: he hoped he might be able to write one last book "full of wisdom about matters of life and death . . . and yet it will be no deadly disappointment if I am compelled to drop it." Then he raised the question lurking beneath their correspondence of nearly three decades—"whether there is ever anything worth achieving in literary reputation."

Four months later Hawthorne would be dead. Longfellow would serve as one of his pallbearers and would stand bareheaded beside Holmes, Whittier, Lowell, Pierce, and Emerson as Mrs. Hawthorne's carriage left Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. In his poem entitled "Concord, May 23, 1864," he mourned the loss of Hawthorne's "magic power," saying, "The unfinished window in Aladdin's tower / Unfinished must remain!" Pastoral images, which had characterized their praise of each other's writings, now render homage to a departed friend: Hawthorne was buried on "that one bright day / In the long week of rain"; he lay "on the hill-top hearsed with pines," where a "tender undertone" expressed "The infinite longings of a troubled breast, / The voice so like his own." [25] The poet's deep affection would be expressed in yet another way: he hung in Craigie House a portrait of Hawthorne as he appeared in the 1860s. [26]

If we ask how well Longfellow knew Hawthorne, it seems fair to answer "as well as any but Sophia and such intimate friends as Bridge or Fields." Longfellow's comment on The Marble Faun—"A wonderful book; with the old, dull pain in it that runs through all Hawthorne's writings" [27]—suggests he understood his friend's dark fictions and responded appropriately to them in private, while confining public comment to the comfortable green sward. His 1837 review of Twice-told Tales had compared its author to a star, his style to running water; and though even at that point he glimpsed Hawthorne's anguish, he chose not to pursue it.

Today's readers, who recognize the great profundity of Hawthorne's writings, must wonder whether Hawthorne honestly shared his contemporaries' high opinion of Longfellow. The answer has to be yes. For the same reasons that he agonized over his own never-ending forays into life's darkest mysteries, he valued Longfellow's constant affirmations and his "grand old strains." As to the even more engrossing question of whether Hawthorne considered himself a superior writer—we can never be sure. Certainly not in the first dozen years of their friendship. But by the time he reached his stride as a novelist, he was surely at least intermittently aware of his own greater heights and depths.

Through the letters to Longfellow, we can enlarge our understanding of the lifelong play of contradictions in Hawthorne's definition of himself as a writer—the mix of self-pity, self-exoneration, and self-affirmation, all controlled by an ironizing skepticism and contained within an enduring commitment to his vocation as writer. Hawthorne was ambitious, and sometimes surprisingly aggressive in pursuing that ambition. Yet he always questioned the importance of his chosen role and his own merit, wondering if his writings could earn the fame, the personal satisfaction, or the money he required. The letters to Longfellow can be examined as artful autobiography: they express his ambition, render it ironic, then reaffirm it in a sequence of affirmation—recoil, or self-effacement and recoil, or flattery of Longfellow balanced by self-assertion. Hawthorne always expressed his will to succeed coupled with an expectation of failure calculated to shield him from disappointment. Thus his ironizing skepticism was itself a pragmatic stance.

Examining Hawthorne's correspondence with Longfellow does not give us a "new" Hawthorne, but we understand him better as a practical careerist who vouchsafed veiled glimpses of his deepest anguish. No serious student of Hawthorne can ignore his self-presentations as a lonely dreamer, as a consular official with thwarted imagination, as a priest-like Rumpelstiltskin cast out of office and anticipating revenge, or as an autumnal writer longing to ripen his last fruit. To no one else but Longfellow did he present himself in all those roles. Perhaps, at some level, he saw Longfellow as his double, his happier self—a literary success even before leaving Bowdoin; beloved on both sides of the Atlantic; and further, a man who never had to worry about making a living.

Finally, as we recognize how generous Hawthorne and Longfellow were with each other, personally and professionally, both seem enlarged. It is true that they both held back from directly sharing each other's deepest sorrows, from venturing into each other's innermost passages. But on the ample plain where they could share both professional achievements and domestic satisfaction, the relationship prospered. Although Hawthorne never did get Longfellow to collaborate on a single publication, he did succeed in scripting his collaboration as an ideal reader—"standing on the green sward, but just within the cavern's mouth."

NOTES

1 Hawthorne's correspondence is cited from typescripts prepared for the forthcoming Centenary edition. I am grateful to L. Neal Smith and Thomas Woodson for providing me with them. Original manuscripts of Hawthorne's letters to Longfellow are at Harvard University except for the letter of 14 October 1846, which is in the collection of C. E. Frazer Clark, Jr.

2 Mosses from an Old Manse (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1974), pp. 32-33.

3 The American Notebooks (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1972), p. 23.

4 Annie T. Fields, "Longfellow: 1807-1882," in Authors and Friends (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1897), p. 5.

5 For information about Longfellow at Bowdoin, see Lawrence Thompson, Young Longfellow (New York: Macmillan, 1938), pp. 30-73 and Samuel Longfellow, ed., Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow with Extracts from His Journals and Correspondence Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1891), I, pp. 26-66.

6 For information about Hawthorne at Bowdoin, see Arlin Turner, Nathaniel Hawthorne (New York: Oxford, 1980), pp. 34-44 and James Mellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne in his Times (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980), pp. 25-34.

7 North American Review, XLV (July, 1837), pp. 59-73.

8 Twice-told Tales (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1974), p. 7.

9 Journal entry for 25 March 1838, manuscript at the Houghton Library, Harvard University; and Longfellow, Life, I, p. 292f.

10 Letter to George Washington Greene dated 22 October 1838, in Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1966), II, p. 107.

11 Hilen, Letters, II, p. 148; journal entry for 10 October 1839 in Longfellow, Life, I, p. 334.

12 Longfellow, Life, I, p. 363.

13 Journal entries for 10 October and 27 October 1846, Houghton Library; and Longfellow, Life, II, pp. 59, 61. Both Longfellow and his wife several times noted in their journals their admiration of Hawthornes tales and "manly beauty," but also their regret that he was rarely talkative or cheerful.

14 See Hilen, Letters, III, p. 124; and Longfellow, Life, II, 56f.

15 Harvard manuscript. The painter was Charles Martin, son of the celebrated English historical painter John Martin.

16 Hilen, Letters, III, p. 14Sf. See Longfellow, Life, II p. 70f on the roles of Conolly and Hawthorne in conveying the story to Longfellow.

17 Reprinted in Randall Stewart, "Hawthorne's Contribution to The Salem Advertiser," American Literature, V (January 1934), pp. 333-35.

18 Hilen, Letters, III, p. 158. Hawthorne replied two days later.

19 The letter is dated 19 June 1849. Longfellow wrote Sumner on the same day inviting him to dinner two days later, when he hoped Hawthorne would be there; but Hawthorne could not attend (Hilen, Letters, III, p. 204). At dinner on June 10, Longfellow and Sumner had "discussed Hawthorne's dismissal from the custom house in terms not very complimentary to General Taylor and his cabinet." (Longfellow, Life, II, p. 153).

20 Letters dated 24 August 1950 and 8 August 1851 in Letters, III, p. 266f. and 306. Longfellow commented that The House of the Seven Gables "has not the tragic simplicity of plot of 'The Scarlet Letter'; but nevertheless it is grander in its variety . . . ." Then he asserted, "I was a true prophet in predicting your success as a Romance Writer!" He closed reporting Field's praise of the Wonder-Book, to be published two months later.

21 Longfellow, Life, II, p. 250. He had noted the previous day that the guests were Hawthorne, Emerson, Clough, Lowell, Charles Norton, and his brother Sam. Hawthorne's letter from Concord is dated 5 October 1852.

22 Hawthorne's comments are from letters dated 30 August and 24 October 1854 and 11 May 1855. Longfellow wrote on 25 April 1855 that he was using Hawthorne "to an alarming extent. But then in return you are in a fair way of finding out all my flirtations" (Hilen, Letters, III, p. 476).

23 Letter to his English friend Henry Bright, 17 December 1860.

25 See Turner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, pp. 392-94, Mellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, p. 578f., and Longfellow, Life, III, pp. 36, 38f, and 40f. The threnody was first published in the August 1864 issue of the Atlantic Monthly.

26 This is a photographic copy of a crayon drawing by the noted portrait artist Samuel Rowse, commissioned by James T. Fields in 1866 and based on a photograph taken by the well-known Boston photographer W.H. Getchell on 19 December 1861. See my forthcoming Portraits of Nathaniel Hawthorne: An Iconography (Dekalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 1983).

27 Longfellow, Life, II, p. 400. The entry is dated 1 March 1860.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

symposium82/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 23-Nov-2009