|

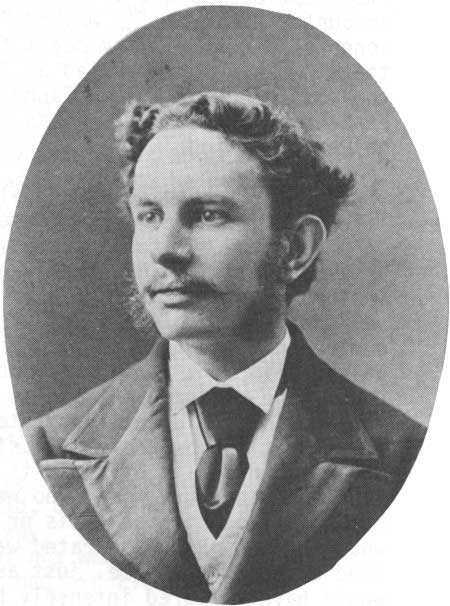

LONGFELLOW

Papers Presented at the Longfellow Commemorative Conference April 1-3, 1982 |

|

LONGFELLOW IN HIS FAMILY RELATIONS

By Edward Wagenknecht

Edward Wagenknecht has taught at the University of Chicago, the Illinois Institute of Technology, the University of Washington, and Boston University, where he is now Professor of English, Emeritus. He has published more than sixty books, including three on Longfellow.

When I came to the Boston area to live in 1947, I was deep in my Cavalcade of the American Novel for Henry Holt and Company. I soon made up my mind that my next substantial enterprise would be a series of books on the great New England writers which would enable me to make use of the rich literary deposits that were now all around me, and I decided to begin with Longfellow.

This was an almost inevitable choice, for Longfellow had been my introduction to Literature with a capital L. I clearly remembered, as a boy in grade school, walking down to the school book store one evening to buy, for fifteen cents, a copy of Evangeline, which was Number 1 in the Riverside Literature Series, and when I was in the sixth grade my mother and I went downtown one Saturday morning and at one of the Chicago department stores purchased a copy of Longfellow's Complete Poems in the Household Edition. These, I suppose, I may call my first "standard" books. I still have them both.

I knew that the poet's late grandson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana, had brought together a great collection of manuscripts at the Longfellow House; so I applied there, and Thomas H. de Valcourt, who was then in charge, welcomed me royally. The Longfellow manuscripts were not moved to the Houghton Library until I had nearly finished my work, and in spite of the many happy hours I have spent at Houghton since in connection with other projects and the friends I have made there, I have always been glad that I became the last scholar to work with Longfellow's manuscripts in his own house.

I suppose I should blush to acknowledge that I repaid Mr. Longfellow's hospitality by falling in love with his wife. What I mean is that one of the first things I discovered was that an extensive collection of her letters and journals was available and that these furnished delightful, as well as, valuable material that so far had been almost completely overlooked. I made up my mind that these manuscripts must be published, not in their entirety (they were too repetitive for that) but in a volume of judicious selections. Fanny Appleton Longfellow died eight years before my mother was born; it was hard to believe that these materials should have been saved all through these years for me.

I ran a "card" in the book review journals. In those days we had not only The New York Times Book Review but the Herald-Tribune Books, and the Saturday Review was still The Saturday Review of Literature. My "card" was seen by John L. B. Williams, then an editor for Longmans, Green, who had previously published me for both Appleton's and Bobbs Merrill. Williams wrote me to say that Longmans would be very glad to publish my book on Longfellow. I replied, "There are going to be two Longfellow books — one about him and the other a selection from Mrs. Longfellow's letters and journals. If you are interested, you will have to contract for both." This I did with some qualms of conscience, since, though I was sure of the quality of Mrs. Longfellow's materials, I was less sure of her sales potential. Williams and Longmans accepted my terms without blinking, however, and I am sure that any feminists who may be present will be delighted to hear that Mrs. Longfellow performed in the book stores more impressively than her husband. She also got an English edition, a small book club selection, and sold serial rights to a metropolitan newspaper. Candor forces me to add, however, that Longfellow, A Full-Length Portrait was afterwards revised and republished by Oxford University Press as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Portrait of an American Humanist, and I suppose that, taking the two editions together, the poet finally overtook his wife. And now if there are any anti-feminists present and lying low, let them take whatever comfort they can find in this!

My subject is "Longfellow in his Family Relations." Men ordinarily spend their lives in two families — that into which they are born and that which, through marriage, they establish. Longfellow wrote that "homekeeping hearts are the happiest," and so they were in his case, except upon those occasions when, through domestic calamities, they were the saddest.

His father, Stephen Longfellow, was a prominent lawyer and a member of the Hartford Convention who served in both the Massachusetts State Legislature and the Congress of the United States. His mother, Zilpah Wadsworth, who was related to John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, was the daughter of a Revolutionary War hero, General Peleg Wadsworth, and at General Wadsworth's house in Hiram, Maine, where the poet spent many happy boyhood days, he came as close to the frontier as Cooper did at Cooperstown or Mark Twain at Uncle John Quarles's farm near Hannibal, Missouri. The Longfellows had eight children, of whom two, both girls, died young.

Stephen Longfellow has sometimes been criticized for not encouraging his son's literary ambitions. This is most unfair, for he was never unsympathetic; he simply felt that the boy should have a profession, not staking his livelihood upon his pen. This is good advice even today, and it was better advice in his time, when the professional American man of letters was virtually non-existent. Zilpah Longfellow was an intelligent woman of courage, strong convictions, and deeply religious spirit. She had humor and sound common sense, as well as a mind of her own, which she did not hesitate to use. The daughter of a general, she had as little sympathy with the military life as her son was to manifest. In later years, when she was an invalid, she notified her children that she expected them to write to her but did not hold herself bound to answer their letters. I think the fact that Longfellow seems to have written more letters to his father than to her has no particular significance. In those days, it seems, there was a species of indelicacy involved in sending a lady's name through the mails, so that even when you wrote to her, you addressed the letter to her husband, as one whose ruder nature might be better able to sustain the shock, though to avoid confusion you might endorse the missive "For Mrs. Longfellow" within protective parentheses.

I get the impression that Anne, afterwards Mrs. Pierce, was the sister who was closest to Longfellow, though since Mary (Mrs. Greenleaf) lived on Brattle Street in a house that still stands, he must have seen a good deal of her. His relations with his brother Alexander, who became an engineer, were perfectly cordial and friendly, but temperamentally he was closer to the youngest son Samuel, a clergy-man, who became his biographer. The only strain Alexander suffered from his relationship to Henry came when people assumed that, as the brother of a famous poet, he ought at least to be able to write valentine verses for them; on such occasions he reminded himself of the young man who, upon being asked whether he spoke German, replied in some confusion, "No, I do not, but I have a brother who plays the German flute." Longfellow's older brother Stephen was a very different story, for Stephen was the problem child of the family, and his life brought little but sorrow to anybody connected with him. "What can have made the difference between our two sons," Zilpah asked her husband in 1825, "educated as they were together and alike." The end of the story, which is terrible, need not be told here; worse still, Stephen passed on his characteristics to his son, and both persons caused the poet much sorrow.

Compared to Fanny Appleton, Longfellow's first wife, Mary Storer Potter, daughter of Judge Barrett Potter of Portland, is a shadowy figure. The couple were married on September 14, 1831, and the marriage lasted only a little over four years. We have few of Mary's letters, and Longfellow burned her journals after her death, which occurred in Rotterdam, after a miscarriage suffered during the trip which Longfellow had undertaken to prepare himself for the Smith Professorship at Harvard. As in the case of Theodore Roosevelt, he seems never to have spoken of his first wife in later years.

He must have seen her in Portland during his youth, but apparently he paid no attention to her until after his first return from Europe, when he was so impressed by her appearance at church one day that he followed her home, though without speaking to her. His very circumspect wooing was conducted through Sister Anne, and the letters he wrote home when Mary died sound unbelievably stiff and formal to modern ears (can any human being, we wonder, ever have been quite so proper in his inner abiding place as these letters sound). I am convinced, however, that this impression is unfair to Longfellow; we have other evidence which testifies to the deep, sincere grief he felt. For some time he went on seeing Mary in everything he tried to read, finding it impossible to center his mind upon anything else; and when he traveled through the Tyrol even the mountains seemed sad. He was never a nature pantheist, however, and even then he was clear sighted enough to attribute this impression not to nature itself but to "my sick soul." In fairness to Mary, it should be noted that though she was only twenty-three when she died, she was no more in awe of her husband than Emerson's remarkable girl-wife, who was dead before she was twenty, was of him, for she calls him "a good little dear," and when, before the offer from Harvard came, he was making frantic efforts to get away from the position he did not like at Bowdoin, she wisely acted as a restraining influence. Longfellow stands at quite the opposite extreme from what is now known as a "confessional" poet; he did not wear his heart nor any other organ upon his sleeve. But Mary had promised him on her deathbed that she would never leave him, and though we do not know how close he ever came to a sense of mystical communion with her, he tells us that he felt "assured of her presence" with him afterwards. This clearly is what he refers to in "Footsteps of Angels," where he speaks of

. . . the Being Beauteous,

Who unto my youth was given,

More than all things else to love me,

And is now a saint in heaven.

With a slow and noiseless footstep

Comes that messenger divine,

Takes the vacant chair beside me,

Lays her gentle hand in mine.

And she sits and gazes at me

With those deep and tender eyes,

Like the stars, so still and saint-like,

Looking downward from the skies.

Yet when all is said and done, the great love of Longfellow's life was Fanny Appleton, the mother of his children, with whom he lived for eighteen years of happiness as perfect as it is given to human beings to know. As he wrote her sister after her tragic death, he still thanked God hourly "for the beautiful life we led together, and that I loved her more and more to the end . . . I never looked at her without a thrill of pleasure; she never came into a room where I was without my heart beating quicker, nor went out without my feeling that something of the light went with her. I loved her so entirely, and I know she was very happy."

To be sure she had given him seven years of pain as a prelude to the eighteen years of happiness. He met her in Switzerland the summer after Mary's death, when she was nineteen, a little more than ten and one-half years younger than he. Her father was the wealthy industrialist Nathan Appleton, and the family lived at 39 Beacon Street, in a house now the home of the Women's City Club; Louise Hall Tharp has told the story of the whole clan in her fine book, The Appletons of Beacon Hill.

|

| Figure 2. Carte-de-Visite photograph of Frances Appleton (1817-1861), possibly by Black & Batchelder, Boston, 1854-1861. Longfellow NHS Collection. |

She was generally considered beautiful, though there are dissenting opinions. Longfellow called her "the Dark Ladie," and the portrait of her by Healy in the Longfellow House is much in the Spanish style, but the lock of hair still kept there is not black but a rich brown, very fine in texture and still radiating light and warmth after more than a hundred years. Her social position was of course higher than that of the Longfellows, and when the engagement was announced, his family seems at first to have been a little in awe of her, partly because she had kept him dangling so long but also because she was what later came to be called a "society girl," but her sweet friendliness and piety soon took care of that.

In Switzerland she seems to have enjoyed her association with "the Prof." as she then called him, but after their return to Boston and Cambridge she gave him no encouragement; aside from the fact that he certainly made the situation worse by writing and publishing Hyperion, in which everybody knew she was Mary Ashburton and he Paul Flemming, it is not easy to see why; indeed she herself seems never in retrospect to have understood it quite clearly. The Hyperion business was quite out of character for so reserved a man as Longfellow; it shows how his nature had been stirred to its depths and goes far toward invalidating the mild, quiet image of him that most persons have. "I shall win this lady," he cries, "or I shall die, and he did not exaggerate his feelings when in 1845 he wrote "The Bridge," looking back upon what he had experienced during those tortured days:

How often, oh how often,

In the days that had gone by,

I had stood on the bridge at midnight

And gazed on that wave and sky!

How often, oh how often,

I had wished that the ebbing tide

Would bear me away on its bosom

O'er the ocean wild and wide!

For my heart was hot and restless,

And my life was full of care,

And the burden laid upon me

Seemed greater than I could bear.

By 1840 he had pretty well made up his mind that it was impossible his hopes should be realized and had adjusted himself to his disappointment as best he could. Then, on an April evening in 1843, the lady who had laid the burden upon him abruptly lifted it, and did it in such a way as to make it clear that she had not read Romeo and Juliet for nothing. He encountered her at the Nortons', a night or two before the scheduled departure of her brother for Europe, and she told him how lonely she expected to be after Tom's departure and then added, "You must come and comfort me, Mr. Longfellow." Whereupon, if she were Juliet, he might have been the Othello who reported that "Upon this hint I spake." She accepted him in a note written on the tenth of May, and he walked forthwith, "with the speed of an arrow," from Brattle Street to Beacon Street, because he was "too restless to sit in a carriage—too impatient and fearful of encountering anyone!" walked "amid the blossoms and sunshine and songs of birds, with my heart full of gladness and my eyes full of tears!" They were married at 39 Beacon Street on July 13. Perhaps the most generous act of Fanny's life was her wedding gift to her husband. It was her European sketch book, inscribed "Mary Ashburton to Paul Flemming."

Their happiness made all other pleasures pale. "My whole life is bound up now in my home and children," she would write. "I am spoiled by it for society, which seems to me very barren and unsympathetic, giving us only glassy surface or sharp corners instead of the genial depth or lofty inspiration we crave." Not only was she completely in love with her husband but she entirely admired him and took as much interest in his work as he did himself, helping him with it in every possible way. Many wives could no doubt have served him quite as devotedly in this aspect, but not many could have done it so intelligently. Though she was far from being what is now known as a strong-minded woman, she took a keen interest in public affairs; it is noteworthy that, unlike many nineteenth century women who were adept at telling people what their husbands thought about this or that issue, Fanny always tells us what she thought. She hated war, and if she had to die young, she died at the right time, just as the Civil War was beginning; she would have suffered intensely because of it and her oldest son's participation and injury in it. Her religious faith was assured, and hers was a deeply devotional spirit, quite free of bigotry. The Appletons, like the Longfellows, were Unitarians, but you will derive no understanding of what she believed by reference to modern Unitarianism. Fanny's theology was Arian, and her Christ was a divine being, subordinate to the Father, but in no sense merely human.

Mrs. Longfellow bore her husband six children: Charles, Ernest, Fanny, Alice, Edith, and Annie Allegra. Everybody knows the names of the three younger girls—"grave Alice and laughing Allegra and Edith with golden hair"—from "The Children's Hour," but most of Longfellow's readers are unaware of even the existence of Fanny, who endured for only a year upon this mortal plane. Yet her birth was notable, for it was when she came into the world that her mother became the first woman in the western world to bear a child under the influence of ether at the Massachusetts General Hospital. We have all heard enough and to spare of the courage of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who introduced inoculation for smallpox into England by inoculating her own daughter, but here are the reputedly timid Longfellows doing an equally daring thing for which they have received no popular credit whatever. All the living Longfellow descendants derive from either Edith (Mrs. Richard Henry Dana III) or Annie Allegra (Mrs. J. G. Thorp). Neither Alice, who lived in the Longfellow House into a time that some of us can remember, nor Charles ever married. Ernest did, but had no children. Fanny loved them all and worried over them and cherished their individualities and saw their limitations as clearly as if they had been somebody she was reading about. There is much material among her papers devoted to their childish doings; no mother can possibly have been more devoted nor guided her children more lovingly, more wisely, nor more unsentimentally.

|

| Figure 3. (above, left) Charles Appleton Longfellow (1844-1893), photograph by Allen & Rowell, Boston, ca. 1865. |

|

| Figure 4. (above, right) Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow (1845-1921), photograph by Whipple, Boston, 1865. |

|

| Figure 5. (below) Photograph of Longfellow's three daughters (left to right): Edith (1853-1915), Alice (1850-1928), Anne Allegra (1855-1934), by F. Gutekunst, Philadelphia, 1876. |

Charley was the harum-scarum member of the family. As a boy he maimed his left hand by the explosion of a gun his father had foolishly permitted him to have, against his mother's advice; later he ran off to the Civil War, where he first came down with camp fever, then got himself dangerously wounded. On both occasions his father went to Washington to nurse him. Oliver Wendell Holmes made literary capital out of "My Search for the Captain," his best-known short piece of prose, written after the wounding of his namesake, the future Supreme Court justice, but Longfellow could never have dreamed of doing such a thing; his devotion, therefore, remains virtually unknown except to his biographers.

Charley Longfellow seems never to have caused his father the kind of anxiety inflicted upon him by his wayward brother and nephew, but his recklessness, extravagance, and disinclination to settle to anything did cause difficulties. There was one hilarious episode in his career. The Longfellows summered at Nahant, and one summer the formidable Jessie Fremont, who was also in residence, had Charley arrested for nude bathing. The case was dismissed when the defense attorney showed that he had bathed in a sufficiently secluded spot so that Mrs. Fremont's modesty could not have been offended without the aid of her binoculars.

I have moved on in my discussion of the children beyond Mrs. Longfellow's lifetime, perhaps because the end of her story is so painful that I have tried to postpone it as long as possible. Though it cannot be passed over, for it represented a turn of fortune's wheel as dramatic as any that mediaeval men ever chronicled, I will deal with it as briefly as I can. It all happened in a moment, in July 1861, just as the Civil War was getting under way. It was a hot, windy day and Mrs. Longfellow was sitting by an open window in the library of the Longfellow House, "sealing up in paper packages some locks of her two younger daughters' hair." By some fluke, a lighted match or some burning wax fell upon her light summer dress, and in a moment she was enveloped in flames. Frightened, she ran for help to her husband in his adjoining study. He wrapped a rug about her and held her close, extinguishing the flames but burning his own face and hands so badly that he was obliged to grow the beard by which we know him best but which Fanny never saw. After a brief period of intense suffering, she was put to sleep with ether and slept into the night, when she awoke calm and free of pain. In the morning she was able to drink some coffee, but she soon fell into a coma from which she never awakened, and before the day was over, she was dead. She was buried at Mount Auburn on July 13, the eighteenth anniversary of her wedding, her head, unmarred by flames, crowned with a wreath of orange blossoms. Her husband, too badly burned to leave his bed, was unable to attend the funeral; half delirous, he heard, through the open door, echoes of the service in the library, where neither men nor women were able to control their sobs.

His mental sufferings were far greater than the physical, and he bore them as everybody who knew him must have been sure he would. Lowell said it best:

Some suck up poison from a sorrow's core,

As nought but nightshade grew upon earth's ground:

Love turned all his to heart's-ease; and the more

Fate tried his bastions, she but forced a door

Leading to sweeter manhood and more sound.

I have said that Longfellow was not a "confessional" poet, and this is true, but, like all poets and all writers, he did build his writings out of the experiences life brought him, and his wife's death yielded one of his greatest sonnets, "The Cross of Snow." He wrote it on July 10, 1879 and put it away in his desk, where it was found after his death and first printed in Samuel Longfellow's biography. The catalyst was a picture in a book of Western scenery, showing a mountain so lofty that it carried a deposit of snow at its heart all summer long in the shape of a gigantic cross. Unlike the "confessional" poets of today, Longfellow freed his record of his own experience from unpleasant egotism and embarrassing exhibitionism by concentrating upon the essential universal humanity that was as significant for his readers as for himself.

In the long, sleepless watches of the night,

A gentle face — the face of one long dead—

Looks at me from the wall, where round its head

The night-lamp casts a halo of pale light.

Here in this room she died; and soul more white

Never through martyrdom of fire was led

To its repose; nor can in books be read

The legend of a life more benedight.

There is a mountain in the distant West

That, sun-defying, in its deep ravines

Displays a cross of snow upon its side.

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

Mrs. Longfellow's death left her husband both father and mother to his children, and it is difficult to see how any man could have functioned more wisely and lovingly in these capacities. William Dean Howells wrote that "all men that I have known, besides, have had some foible, . . . or some meanness, or pettiness, or bitterness; but Longfellow had none, nor the suggestion of any." He was not the man to romp with children, and he seems to have been more at home with little ones than with growing boys and girls, but his sympathy and understanding never failed, and when comfort was needed, he was always there to give it. "It would be in vain for me to try to send you any news," he once wrote Annie Allegra when they were separated. "I can only send you my love, and that is anything but news. It is as old as you are." When the children were small, he had an endless store of childish treasures to amuse them, and he never wearied of making up stories for them, some of which have survived in manuscript. Nor was his interest confined to his own offspring. Eleanor Hallowell Abbott, who was "little in Cambridge when everybody else was big," has recorded how she and the other children she knew would throw themselves into his "hospitable" arms when they met him on the street, and there is the delightful story of the boy who, shocked at Longfellow's admission that he had no copy of Jack and the Beanstalk in his library, went out and bought him one. Longfellow insisted on the child's autographing the little book and promised to keep it among his dearest treasures.

There is one bibliographical problem in this connection. Everybody knows the famous doggerel:

There was a little girl

And she had a little curl

Right in the middle of her forehead.

And when she was good

She was very, very good,

But when she was bad she was horrid.

Did Longfellow write this or did he not? His son Ernest claimed that he did, but none of the other members of the family seem to have agreed with him, and there is certainly no conclusive evidence. The one thing that is certain is that he did not write the other stanzas sometimes appended to it. There was a learned and probably conclusive discussion of the matter by Sidney Kramer in the 1946 volume of the Bibliographical Society of America Papers.

Longfellow was fifty-four years old when Fanny Appleton died, and he had twenty-one more years to live. Was he ever seriously interested in any other woman? Ambrose Bierce says that he who thinks he has loved twice has not loved once. However that may be, let us look at the record.

To begin with, completely proper as Longfellow's conduct always was, there can be no question that he was sensitive to the beauty of women. "You were ever an admirer of the sex," writes one who knew him early, "but they seemed to you something enshrined and holy, — to be gazed at and talked with and nothing further," and Longfellow's brother Sam adds that it might have been said of him as of Villemain that "whenever he spoke to a woman it was as if he were offering her a bouquet of flowers." Even in his old age, Mrs. James T. Fields heard him say to himself, as he stood near the staircase at a formal entertainment, "Ah, now we shall see the ladies come downstairs!"

Longfellow enjoyed friendships with a number of women after his wife's death, most of them literary or musical ladies who had sought him out for his fame or in admiration for his work. I shall mention only three. I am quite sure that Longfellow was never immoderately attracted by Blanche Roosevelt, who appeared in the opera made from The Masgue of Pandora, but he welcomed her to his house and entertained her there, much to the displeasure of his daughters, who seem to have disliked her and suspected her of "using" him. After his death she published a rather silly book called The Home Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, which she claimed had been approved by him. Blanche Roosevelt may have been "a very nice person," as Longfellow told Edith, but I get the idea that she was quite capable of using her contacts with him to her own honor and profit. But she was not important enough in his life so that anything more needs to be said about her, nor, for that matter, can it be said authoritatively on the basis of the information we have.

In a sense, Sherwood Bonner, the Mississippi local color writer, "used" Longfellow too; unlike Blanche Roosevelt, she even enjoyed his financial bounty and that of his daughter Alice after his death, but this talented, restless, ambitious, unfortunate woman deserves considerable sympathy; after having suffered many sorrows and misfortunes, she died, at the age of thirty-four, only a year after Longfellow himself. There is said to be unpublished manuscript material bearing upon Longfellow's acquaintance with Sherwood Bonner, but nobody seems to know where it is. All I can say is that there is nothing in any of the letters I have read that could possibly be interpreted to indicate that he was ever anything to her except a kindly, affectionate, elderly patron and friend.

There is another woman, however, who deserves more serious consideration, a beautiful English girl named Alice Frere, the daughter of William Frere of Bitton, Judge of the High Court of Bombay, and later Mrs. Godfrey Clerk. She was thirty-four years Longfellow's junior, and he met her in Boston, when she was visiting there with her father in 1867. A number of letters passed between them while she was in Boston and others later. She lived with her husband, a major in the British army, in Egypt and India, bore at least one son, and in 1873 published a volume of tales translated from the Arabic, of which she sent Longfellow a copy. On the eighth of April in 1867 Alice Frere wrote Longfellow a letter in Boston in which she told him that she had been engaged to Clerk for three years but that financial difficulties had hitherto prevented their union, and his reply to this letter contains two postscripts which, to say the least of it, tease curiosity. The first reads:

I keep very sacred and precious the memory of Monday evening. It was the revelation of a beautiful soul; a Song without Words, whose music I shall hear through the rest of my life.

And the second:

The secret I told you I know is safe in your keeping. I could not help telling it to you. It was the cry of my soul. And yet I would not have told it had I known yours. Of that I beg you to tell me more. It interests me very deeply. Speak to me as frankly as I have spoken to you.

That is all we know. But if Longfellow knew any woman after Fanny's death who interested him deeply, Alice Frere has the best claim.

My mind goes back to a story Harry Dana used to tell about one of my predecessors among the researchers in the archives at the Longfellow House. This gentleman, a good scholar, whose name you would all recognize if I were to speak it, kept hoping against hope that in some letter or journal of Longfellow's he might find something lively. One day he came out from the room where he had been reading in high spirits. He had discovered Longfellow, during his first European sojourn, expressing enthusiasm over a "Frau Boudour"; here at last was something he could hang on to! "Frau Boudour"? said Dana. "I do not recall any such name in the Longfellow papers. It doesn't sound quite right. 'Frau' is German, and 'Boudour' sounds French. Better let me look at the passage." When he did, he found that what Longfellow was being enthusiastic about was the poetry of the Troubadours.

It makes one wonder, does it not, how many "Frau Boudours" have wormed their way into literary history because some scholar could not read the author's handwriting?

Longfellow's contacts and correspondence with Alice Frere were first made known in my Longfellow, A Full-Length Portrait, and I was much afraid that the reviewers would play it up and exaggerate its importance out of all proportion to its place in the book and in Longfellow's life. To my astonishment, not one reviewer (and there were many) even mentioned it. But after thinking the matter over, I concluded that this was what I ought to have expected after all. I had not dug up anything that was either discreditable to Longfellow and Alice Frere or that could be misconstrued as such. Had I done so, I might have created a legend comparable to that which has developed around Dickens and Ellen Ternan, whom one commentator parrots another in describing as his mistress, although nobody has ever ventured to reply to my book, Dickens and the Scandalmongers, in which all the extant evidence bearing upon this matter is weighed and shown to be inconclusive.

Whatever Longfellow may or may not have felt about Alice Frere, I am sure his association with her remained a fragrant memory during his last years. Did he think of her, I wonder, when he wrote these lines in Tales of a Wayside Inn:

Ships that pass in the night, and speak each other in passing,

Only a signal shown and a distant voice in the darkness;

So on the ocean of life, we pass and speak one another,

Only a look and a voice, then darkness again and a silence.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

symposium82/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 23-Nov-2009