|

Manzanar National Historic Site California |

|

NPS photo | |

We were judged, not on our own character... but simply because of our ethnicity.

—Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga

ONE CAMP • 10,000 LIVES ONE CAMP • 10,000 STORIES

In spring 1942, the US Army turned the abandoned townsite of Manzanar, California, into a camp that would confine over 10,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants. Margaret Ichino Stanicci later said, "I was put into a camp as an American citizen, which is against the Constitution because I had no due process. ... It was only because of my ancestry."

For decades before World War II, politicians, newspapers, and labor leaders fueled anti-Asian sentiment in the western United States. Laws prevented immigrants from becoming citizens or owning land. Immigrants' children were born US citizens, yet they too faced prejudice. Japan's December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor intensified hostilities toward people of Japanese ancestry.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the military to remove "any or all persons" from the West Coast. Under the direction of Lt. General John L. DeWitt, the Army applied the order to everyone of Japanese ancestry, including over 70,000 US citizens. DeWitt said, "You just can't tell one Jap from another. ... They all look the same. ... A Jap's a Jap."

They were from cities and farms, young and old, rich and poor. They had only days or weeks to prepare. Businesses closed, classrooms emptied, families and friends separated. Ultimately, the government deprived over 120,000 people of their freedom. Half were children and young adults. Ten thousand were incarcerated at Manzanar. From this one camp came 10,000 stories.

We could only carry what we could carry, and my suitcase was full of diapers and children's clothes.

—Fumiko Hayashida

TWO FAMILIES • TWO STORIES

Before the war, the Miyatake and Maruki families lived near each other in Los Angeles. In Manzanar, they lived in neighboring blocks, yet their experiences were far apart. The Miyatakes' eldest son Archie met and fell in love with Takeko Maeda. They later married and spent over 70 years together.

The Marukis' eldest daughter Ruby came to Manzanar married and pregnant. She died in the camp hospital on August 15, 1942, along with the twin girls she was delivering. Decades later, Ruby's youngest sister Rosie said, "My mother never got over it. It just broke her heart."

CONFLICT

Why didn't the government give us the chance to prove our loyalty instead of herding us into camps?

—Joseph Kurihara

People's diverse reactions to incarceration and conditions in Manzanar often led to conflict, erupting on December 6, 1942. A large crowd gathered to protest the jailing of Harry Ueno. The confrontation escalated and military police fired into the crowd, killing two men and injuring nine others. Soon the consequences of what came to be known as the Manzanar "riot" reverberated through all ten camps. Government officials issued a controversial questionnaire to identify and segregate those they deemed "disloyal." Koo Sakamoto and her husband gave conflicting answers. She was 19 and pregnant with their second child when her husband was sent never saw each other again.

REMEMBRANCE

It was shocking to your soul, to your spirit, and it took many years for people to talk about it.

—Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston

The Manzanar camp closed on November 21, 1945, three months after the war ended. Despite having regained their freedom, some people found life equally difficult after the war. Most spent decades rebuilding their lives, but few spoke openly about their wartime experiences. Buddhist and Christian ministers returned to the cemetery each year to remember the dead. In 1969, a group of activists came on their own pilgrimage of healing and remembrance. With the formation of the Manzanar Committee, this pilgrimage grew into an annual event attended by over one thousand. Efforts to remember and preserve the camp led to the creation of Manzanar National Historic Site in 1992.

APOLOGY

America is strong as it makes amends for the wrongs it has committed ... we will always remember Manzanar because of that.

—Sue Kunitomi Embrey

In the 1980s, a congressionally authorized commission concluded "race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership" led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. It recommended a presidential apology and individual payments of $20,000. After receiving her apology letter from President George H. W. Bush, Miho Sumi Shiroishi "felt as though the shame of all these years had been lifted and I was able to talk about the experience with much more ease. This letter of apology has meant a great deal to me, more than anyone can imagine."

Let It Not Happen Again

I have come to a conclusion after many, many years that we must learn from our history and we must learn that history can teach us how to care for one another.

—Rose Hanawa Tanaka

The story of Manzanar has not ended—Japanese Americans and others keep it alive. At age 95, Fumiko Hayashida testified before Congress to support the Nidoto Nai Yoni ("Let it not happen again") memorial on Bainbridge Island, Washington. She was photographed at that site in 1942, holding her daughter—an image that became an icon of the World War II Japanese American experience. At age 100, Fumiko and her daughter Natalie returned to Manzanar for the first time since World War II. Today, thousands of people who visit Manzanar and other sites of conscience feel connected to these places and their stories. At Manzanar, some see their own struggles reflected in the injustices that over 10,000 Japanese Americans faced here.

There is not much there anymore in the way of structures... but a lot of memories remain.

—Miho Sumi Shiroishi

Reading the Manzanar Landscape

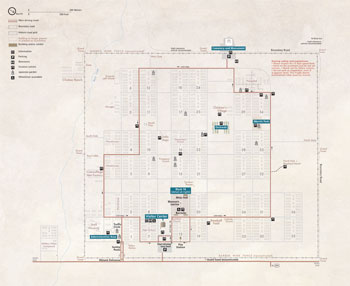

(click for larger map) |

After the war, the government removed most of the structures, and buried gardens and basements. As time passed, Manzanar was further buried, both in sand and in memory. Today, when visitors see Manzanar, they may think there's nothing out there. Yet for those who learn to read the landscape, the place comes to life. A pipe sticking out of the ground becomes a water faucet where children splashed their faces in the summer heat. A foundation reveals the shoe prints of a child who crossed the wet cement. Ten iron rings embedded in a concrete slab evoke the humiliation of ten women forced to sit exposed next to strangers, enduring private moments on public toilets.

Whether driving the 3-mile self-guiding tour or exploring Manzanar on foot, visitors can see a number of Japanese gardens and ponds. People built gardens to beautify the dusty ground outside their barracks. Others built larger gardens near mess halls where people waited in line for meals three times a day. The most elaborate garden was Merritt Park, which Tak Muto, Kuichiro Nishi, and their crew built as Manzanar's community park. In 2008, the Nishi family helped park staff remove decades of soil to reveal the park.

The National Park Service continues to uncover and preserve historic features, including elements of the early 1900s farming town of Manzanar. This land is home to the Owens Valley Paiute, whose own stories have been passed down through millennia and are an important part of the history of Manzanar.

TO READ MANZANAR'S LANDSCAPE, LOOK FOR:

• Rocks arranged to personalize barracks "yards" or create gardens

• Sidewalks that led to doorways

• Water pipes that stood at corners of barracks

• Concrete foundations of latrines, laundry rooms, and ironing rooms

• Concrete blocks that supported barracks

Many pieces from Manzanar's past lie scattered on the ground. It is against federal law to disturb or collect these items.

Administration Area

Over 200 War Relocation Authority (WRA) staff—and often their

families—lived and worked here, trying to reconcile directives from

Washington, DC, with the realities of managing an incarcerated community. Erica

Harth recalled, "The administrative section where we lived was literally white.

Its white painted bungalows stared across at the rows of brown tarpaper

barracks." Scores of Japanese Americans also worked in WRA offices.

Cemetery Monument

Catholic stone mason Ryozo Kado built this obelisk in 1943 with help from

residents of Block 9 and the Young Buddhist Association. On the east face,

Buddhist Reverend Shinjo Nagatomi inscribed kanji characters that mean "soul

consoling tower." People attended religious services here during the war. Today

the monument is a focal point of the annual pilgrimage, serving as a symbol of

solace and hope.

City of Barracks

Manzanar was arranged into 36 blocks. In most blocks, up to 300 people crowded

into 14 barracks. Initially, each barracks had four rooms with eight people per

room. Everyone ate in a mess hall, washed clothes in a public laundry room, and

shared latrines and showers with little privacy. The ironing room and recreation

hall offered spaces for classes, shops, and churches. Over time, people

personalized their barracks and the blocks evolved into distinct

communities.

MORE INFORMATION

The Manzanar Visitor Center features exhibits about the camp and area history,

plus a film and bookstore. Block 14 includes exhibits about the challenges of

daily life. The grounds are open daily, sunrise to sunset. Check the park

website for visitor center hours, programs, events, and special exhibits.

Safety and Regulations It is against federal law to disturb or collect artifacts. • Drive only on the designated tour road. • Wear sturdy footwear, a hat, and sunscreen. • Drink lots of water. • Pets are allowed outside if leashed. • Firearms are prohibited in federal buildings.

Emergencies dial 911

Accessibility We strive to make facilities, sen/ices, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment Manzanar National Historic Site — March 3, 1992 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942 (Togo Tanaka, January 1943)

Accessibility Self-Evaluation and Transition Plan Overview: Manzanar National Monument, California (November 2017)

An Annotated Bibliography for Manzanar National Historic Sites (Arthur A. Hansen, Debra Gold Hansen, Sue Kunitomi, Jane C. Wehrey, Garnette Long and Kathleen Frazee, February 1995)

An Historiography of Racism: Japanese American Internment, 1942-1945 from Historia, Volume 13 (John Rasel, 2004)

Condition Assessment and Preservation Plan for Various Structures, Manzanar National Historic Site (Mark L. Mortier, December 31, 2000)

Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (HTML edition, UW Press 2002 rev. ed.) Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 74 (Jeffrey F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord and Richard W. Lord, 1999)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Manzanar National Historic Site (2004)

Cultural Landscape Report, Manzanar National Historic Site (2006)

Draft General Management Plan & Environmental Impact Statement, Manzanar National Historic Site (December 1995)

Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center: Historic Resource Study, Special History Study, Volume One (Harlan D. Unrau, 1996)

Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center: Historic Resource Study, Special History Study, Volume Two (Harlan D. Unrau, 1996)

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942 (J.L. DeWitt, 1943)

Foundation Document, Manzanar National Historic Site, California (Draft, August 2015)

Foundation Document, Manzanar National Historic Site, California (August 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Manzanar National Historic Site, California (January 2016)

Garden Management Plan: Gardens and Gardners at Manzanar (Jeffrey F. Burton, 2015)

General Management Plan & Environmental Impact Statement, Manzanar National Historic Site, California (August 1996)

Geologic Map of Manzanar National Historic Site (March 2009)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Manzanar National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/130 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2009)

Historic Preservation Report — Volume I: Manzanar National Historic Site Record of Treatment - Manzanar Historic Structures Rehabilitation Project (Glenn D. Simpson, FY2001)

Historic Preservation Report — Volume II: Manzanar National Historic Site Documentation Report - Inscription and Graffiti Documentation (Glenn D. Simpson, FY2001)

Historic Preservation Report — Volume III: Manzanar National Historic Site Record of Treatment - Manzanar Concrete Feature Conservation (Robert Hartzler, FY2001)

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study — The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center Volumes One and Two (HTML edition) (Harlan D. Unrau, 1996)

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study — The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center — Volume One (Harlan D. Unrau, 1996)

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study — The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center — Volume Two (Harlan D. Unrau, 1996)

Historic Structure Report: The History and Preservation of the Manzanar Auditorium-Gymnasium, Manzanar National Historic Site, California (Robert L. Carper, Gordon Chappell, Robbyn Jackson, Andrew M. Roberts, Elizabeth Smith, Dave Snow and Charles Svoboda, December 1998)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Manzanar National Historic Site, 2004 (Daniel J. Stynes, June 2006)

Inventory of Amphibians and Reptiles at Manzanar National Historic Site, California Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2006-1232 (Trevor B. Persons, Erika M. Nowak and Scott Hillard, September 2006)

I Rei To: Archeological Investigations at the Manzanar Relocation Center Cemetery, Manzanar National Historic Site, California Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 79 (Jeffery F. Burton, Jeremy D. Haines, and Mary M. Farrell, 2001)

Japanese American Confinement Sites Digital Collection (National Japanese American Historical Society)

Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Barbara Wyatt, ed., August 2012)

Japanese-American Internment Sites Preservation (January 2001; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Manzanar National Historic Site (October 2018)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Manzanar National Historic Site (August 2007)

Manzanar Free Press (1942-45) Selected Issues: Vol. 1 No. 1, April 11, 1942 • Vol. 3 No. 23, March 20, 1943 • Vol. 4 No. 1, September 10, 1943 • Vol. 16 No. 4, September 28, 1945

Manzanar National Historic Site (audio and video)

Museum Management Plan, Manzanar National Historic Site (Blair Davenport, Steve Floray, Mark Hachtmann, Brenna Lissoway, Alisa Lynch, Diane Nicholson and Pamela Beth West, 2012)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Manzanar War Relocation Center (Manzanar) (Sue Kunitomi Embrey, July 31, 1975)

Manzanar War Relocation Center (Manzanar Internment Camp) (Erwin N. Thompson, August 12, 1984)

Native American Consultations and Ethnographic Assessment: The Paiutes and Shoshones of Owens Valley, California (Lawrence F. Van Horn, November 1995)

Natural Resource Condition Assessments for Six Parks in the Mojave Desert Network NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR-2019/1959 (Erica Fleishman, Christine Albano, Bethany A. Bradley, Tyler G. Creech, Caroline Curtis, Brett G. Dickson, Clinton W. Epps, Ericka E. Hegeman, Cerissa Hoglander, Matthias Leu, Nicole Shaw, Mark W. Schwartz, Anthony VanCuren and Luke Z. Zachmann, August 2019)

Nicholson Papers

Introduction to the Nicholson Papers (Tom Ryan, 2020)

Herbert V. Nicholson and His Son (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Going to Karuizawa (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Japanese Feudal History (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Feudal Observation Sites (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Our Return to Japan (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Canadian Academy (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Coleville (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Riding Trains Right After the War (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

The Merchant Potter (Samuel O. Nicholson, 2020)

Oral History Interviews, Manzanar National Historic Site (audio and video)

Orchard Management Plan, Manzanar National Historic Site (2010)

Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Part 1 (HTML edition) (December 1982)

Self-Guided Tours of Manzanar (Manzanar Committee, undated)

Snapshots of Confinement: Memory and Materiality of Japanese Americans' World War II Era Photo Albums (©Whitney J. Peterson, Master's Thesis University of Denver, November 2018)

Soil Survey of Manzanar National Historic Site, California (2013)

Teacher's Guide Primary Source Set: Japanese American Internment (undated)

The Archeology of Somewhere: Archeological Testing Along U.S. Highway 395, Manzanar National Historic Site, California Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 72 (Jeffrey F. Burton, 1998)

The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (1946)

The Lost Years: 1942-1946 (Sue Kunitomi Embrey, ed., ©Manzanar Committee, 1972, all rights reserved)>

The Manzanar Pilgrimage: A Time for Sharing (©Manzanar Committee, 1981, all rights reserved)

The Oasis (Mojave Desert Network)

The Sands of Manzanar: Japanese American Confinement, Public Memory, and the National Park Service, Manzanar National Historic Site Administrative History (Theodore Catton and Diane L. Krahe, 2018)

Three farewells to Manzanar / The archeology of Manzanar National Historic Site, California, Part 1 Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 57 (Jeffrey F. Burton, et al., 1996)

Three farewells to Manzanar / The archeology of Manzanar National Historic Site, California, Part 2 Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 57 (Jeffrey F. Burton, et al., 1996)

Three farewells to Manzanar / The archeology of Manzanar National Historic Site, California, Part 3 Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 57 (Jeffrey F. Burton, et al., 1996)

Treasure in Earthen Vessels: God's Love Overflows in Peace and War (©Herbert V. Nicholson, December 1974, with permission of his son, Samuel O. Nicholson, all rights reserved)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Manzanar National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/MANZ/NTRT-2014/868 (Dan Cogan and Jeanne Taylor, May 2014)

Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans (©Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, 2009)

Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans (©Roger Daniels, 2005)

Interpretive Center Grand Opening, Manzanar NHS - Part 1 (2004)

manz/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025