|

Moores Creek National Battlefield North Carolina |

|

NPS photo | |

The Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, February 27, 1776

At Moores Creek Bridge a brief, violent clash at daybreak on February 27, 1776, saw patriots defeat a larger force of loyalists marching toward a rendezvous with a British naval squadron. Brief but important, the battle effectively ended royal authority in the North Carolina colony and stalled a full-scale British invasion of the South. The patriot victory emboldened North Carolina, on April 12, 1775, to instruct its delegation to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia to vote for independence from Britain. It was the first American colony to do so.

As economic and political issues with Great Britain became open rebellion in the mid-1770s, North Carolina was a divided colony: patriots would fight for independence, but loyalists opposed war. Loyalists were mainly Crown officials and wealthy merchants and tidewater planters, along with Scottish Highlanders—recent immigrants—and western, frontier Carolinians. Frontiersmen had unsuccessfully rebelled in 1771 against the colony's legislature and court system that coastal interests controlled. Patriot and loyalist numbers were even, but feelings weren't so clear cut. Neither side at first wanted to kill the other. Each hoped the other would give in.

First Moves Toward War News of the Lexington and Concord fighting in April 1775 further eroded royal authority. Unable to stop revolution in the colony, Royal Governor Josiah Martin abandoned the capital of New Bern and fled to Fort Johnston on the lower Cape Fear River, but by mid-July, North Carolina militia forced him to flee offshore to the British warship Cruizer. In exile Martin laid plans to re-take North Carolina. He would raise an army of 10,000 and march it to a coastal rendezvous with Lord Cornwallis, Sir Henry Clinton, and naval officer Sir Peter Parker. Martin persuaded his London and North American superiors that his plan would restore royal rule in the Carolinas—but he could raise only 1,600 loyalist soldiers.

Patriots had not been idle. In August and September 1775, they set up a Provincial Council government and, as the Continental Congress had recommended, raised two regiments of the Continental Line and several battalions of minutemen and militia. At news of loyalists assembling at Cross Creek (Fayetteville), the patriots gathered forces, too. In Wilmington they threw up breastworks and prepared to fight. New Bern authorities mustered the district militia under Col. Richard Caswell with orders to join other militia to counter the loyalists. Col. James Moore, senior officer of the 1st North Carolina Continentals and the first to take the field, was given command.

Loyalists planned to advance along the Cape Fear River to the coast, provision British naval troops, and join them in conquering the colony. On February 20, 1776, the loyalist force under British Gen. Donald MacDonald moved toward the coast. Blocked by Moore's forces at Rockfish Creek, he decided instead to march eastward toward Caswell's patriot force—expecting little opposition on his way to Wilmington.

Outmaneuvered by MacDonald's shift, for the next five days the patriots sought possession of the bridge over Moores Creek, 20 miles above Wilmington. A crucial crossing point, it was the patriots' last chance to halt the loyalists' march to the coast—where the patriots were not likely to stop a combined loyalist army and naval force. Moore sent Col. Alexander Lillington and his men to join Caswell. Then Moore sailed for the coast with his patriots, landing just north of Wilmington and blocking the route between Moores Creek bridge and the sea.

Engagement at the Bridge First to arrive at Moores Creek bridge on February 25, Lillington quickly grasped the position's defensive advantages. The creek wound through swampy terrain, and the bridge was the only nearby place to cross it. To control the crossing, Lillington's 150 men built a low earthwork overlooking the bridge and its eastern approach. Joining Lillington the next day, Caswell's 850 men built an earthwork on the bridge's other side. MacDonald's loyalists, 1,500 strong but with arms for fewer than 800, were now camped six miles away.

Losing the race to the bridge forced MacDonald to choose—avoid a battle again, or fight? He sent a letter offering the patriots a last chance to lay down arms and swear allegiance to the Crown. The patriots declined. A scout reported that patriot troops were vulnerable—but he did not know earthworks and cannon waited east of the creek. At a council of war the loyalists decided to attack. At 1:00 am, February 27, with Maj. Donald McLeod commanding, the loyalists started marching to the bridge. Swampy terrain hindered them. During the night Caswell's patriots abandoned camp, withdrew across the creek, removed the bridge planks, and greased the girders. Posting artillery to cover the bridge, the patriots awaited advancing loyalists.

Discovering Caswell's camp deserted, McLeod's loyalists regrouped in nearby woods to wait for daybreak. Gunfire erupted near the bridge before dawn, but McLeod could wait no longer. With broadswords drawn, his loyalists rushed the partly demolished bridge. When they were 30 paces from the patriot earthwork, they met musket and artillery fire. The advance party was all but cut down in minutes, and the whole force had retreated. Over 30 loyalists were killed, and 40 wounded. Only one patriot died. The patriots had blocked the loyalist march to the coast.

Within weeks most loyalists were captured. Spoils taken included 1,500 rifles, 350 "guns and shot-bags," 150 swords and dirks, and £15,000 sterling. Leaders were imprisoned or banished from the colony. Some went to Nova Scotia, and some returned to Scotland. Most loyalist soldiers were paroled to their homes.

The battle was small, but its implications loomed large. The victory showed the surprising patriot strength in the countryside. It discouraged growth of loyalist sentiment in the Carolinas and spurred revolutionary feeling in the colonies. The British seaborne force, finally arriving in May, moved on to Sullivans Island off Charleston, S.C. In late June patriot militia there repulsed Sir Peter Parker's land and naval attack, ending for two years any British hopes of squashing rebellion in the South.

Had Britain conquered the South in early 1776, historian Edward Channing concluded, "it is entirely conceivable that rebellion would never have turned into revolution." Here at Moores Creek, and then again at Sullivans Island, "Carolinians turned aside the one combination of circumstances that might have made British conquest possible."

Traces of the Past

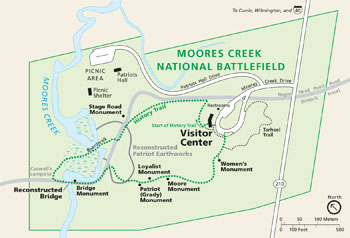

(click for larger map) |

This 87-acre park preserves the site of the Revolutionary War Moores Creek Bridge battle fought February 27, 1776, between loyalists supporting the British Crown and patriots of North Carolina. Original remains are the bridge site and a stretch of the old Negro Head Point Road. In 1856 a Wilmington newspaper reported that some original bridge timbers and earthwork traces could be seen. The National Park Service works to preserve and protect this site unimpaired for this and future generations. Over 20 National Park System sites primarily commemorate the Revolutionary War.

Earthen mounds seen today mark the line of earthworks built by Col. Alexander Lillington's troops, the first patriots to reach the bridge. The earthworks used the high ground to advantage. One end was anchored in swampy ground, the other by the creek itself. In this position Lillington could fend off enemies fording the creek to attack his side or rear. Here he also straddled the road loyalists must use to try to cross the bridge. Rehabilitated in the late 1930s, these earthworks line up accurately, but their true, original height is not known.

A Tour of the Battlefield

Allow at least 90 minutes to tour the battlefield and see the visitor center

exhibits and video. A diorama depicts the bridge scene as patriots opened fire

early on February 27, 1776. Original weapons—a Highland pistol, Brown Bess

musket, half-pounder swivel gun, and broadsword—are displayed.

The History Trail (1 mile) begins at the visitor center and connects the battlefield's historical features in an easy stroll. It briefly follows the trace of historic Negro Head Point Road, dating from 1743 and used by both sides in 1776. A boardwalk across Moores Creek leads to Caswell's campsite's loyalist-eye view of the bridge. Crossing the bridge takes you to Bridge Monument and the patriot earthworks where the partly dismantled bridge was key to the patriot victory.

The Patriot (Grady) Monument, erected in 1857, commemorates both the battle and Pvt. John Grady, the only patriot killed. Nearby, the Loyalist Monument, dedicated in 1909, honors supporters of the British cause who "did their duty as they saw it;" the James Moore Monument honors a Moore's Creek Battleground Association president; and a monument honors heroic women of the Cape Fear region and the role of women in the American Revolution.

The Tarheel Trail (0.3 mile) begins near where the History Trail ends. Pathside exhibits tell about producing naval stores (tar; pitch, and turpentine), the region's chief Revolution-era industry.

About Your Visit

The battlefield is 20 miles northwest of Wilmington, N.C. From Wilmington take

I-40 or U.S. 421 north to the junction with N.C. 210, then travel west on 210 to

the park entrance. The battlefield is open 9 am to 5 pm daily, except December

25 and January 1. Groups may contact the park staff in advance to arrange a

guided tour.

Safety

• Be careful: banks along the creek are slippery. • The park is home

to several species of poisonous snakes; do not approach or startle snakes or any

other wild animals.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment

Moores Creek National Battlefield — September 8, 1980 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Background Study of Fences and Monuments at Moores Creek National Monuments (Jamie Blankenship, August 1, 1989)

A Floristic Study of the Vascular Plants on 11.77 Acres of Moores Creek National Battlefield (David J. Sieren, July 15, 1984)

An Administrative History: Moores Creek National Battlefield (Michael A. Capps and Steven A. Davis, June 1999)

An Archeological and Electromagnetic Survey of Moores Creek National Battlefield (31PD273), Pender County, North Carolina SEAC Technical Reports No. 6 (John E. Cornelison, Jr., 1997)

Anuran Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield: 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2015/982 (Briana D. Smrekar and Michael W. Byrne, October 2015)

Archeological Overview and Assessment, Moores Creek National Battlefield (Lou Groh and Patricia Dietrich, 1998)

Assessment of Water Resources and Watershed Conditions in Moores Creek National Battlefield, North Carolina NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2009/132 (Michael A. Mallin and Matthew R. McIver, July 2009)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Moores Creek National Battlefield: Summary of Results NPS 324/186749 (K.M. Peek, H.L. Thompson, B.R. Tormey and R.S. Young, November 2022)

Foundation Document, Moores Creek National Battlefield, North Carolina (December 2012)

Foundation Document Overview, Moores Creek National Battlefield, North Carolina (February 2013)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Moores Creek National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2006/012 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, July 2006)

Hydrologic Restoration of a Wet Pine Savanna at Moores Creek National Battlefield, North Carolina Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2001/293 (Scott W. Woods and Joel Wagner, December 2001)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRDS—2011/304 (Michael W. Byrne, Joe C. DeVivo and Brent A. Blankley, September 2011)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield: 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2017/1082 (Elizabeth A. Kurimo-Beechuk and Michael W. Byrne, January 2017)

Master Plan, Moores Creek National Military Park (HTML edition) (1969)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Moore's Creek National Military Park (Raymond L. Ives, March 31, 1975, June 1976)

Moore's Creek National Military Park (Boundary Increase) (December 12, 1986)

Park Newspaper (Living History Guild): January 2017 • April 2017

Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2011/178 (Michael W. Byrne, Briana D. Smrekar, Marylou N. Moore, Casey S. Harris and Brent A. Blankley, July 2011)

Terrestrial Vegetation Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield: 2022 Data Summary NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/211 (M. Forbes Boyle and Mallorie A. Davis, November 2024)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2012/250 (Michael W. Byrne, Sarah L. Corbett and Joseph C. DeVivo, February 2012)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Moores Creek National Battlefield: 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2017/1093 (Sarah Corbett and Michael W. Byrne, March 2017)

Vegetation Mapping at Moores Creek National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2012/319 (Rachel H. McManamay, Anthony C. Curtis and Michael W. Byrne, May 2012)

The Moore's Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776 (Hugh F. Rankin, extract from North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. XXXX No. 1, January 1953)

mocr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025