|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART FOUR: DEPRESSION AND WAR YEARS, 1930-1945 |

XII. RESEARCH AND INTERPRETATION IN THE 1930s

INTRODUCTION

In the years prior to the New Deal, the Park Service strove to build up its interpretive program and its research capabilities. Tomlinson, together with all park superintendents, kept statistics on the number of contacts between park visitors and what was then called the Education or Nature Guide Department, demonstrating year after year that this function of the park administration was a proven success with the public. In the area of research, the NPS made important strides with the system-wide wildlife survey undertaken by George M. Wright, Ben H. Thompson, and Joseph M. Dixon, the appointment of John D. Coffman as NPS chief of forestry, and the establishment of a Branch of Research and Education headed by Assistant Director Harold C. Bryant, all in 1930-31. Wright's and Thompson's field work in Mount Rainier and Coffman's detailed report on fire protection in the park were two early results of this new push. Thus, the Park Service had already established a commitment to research and interpretation before the coming of the New Deal. The main significance of the New Deal was that it gave these developing programs a large boost of funding. Mount Rainier National Park's research and interpretive programs grew substantially in this era.

The funding increases had a collateral effect. As the Branch of Research and Education grew, it obtained greater respect within the service's hierarchy. Park naturalists and experts in the NPS Wildlife Division were soon advising on policy matters with almost as much frequency as the park landscape architects and their superiors in the NPS Landscape Division. In Mount Rainier National Park, Tomlinson sought the advice of biological experts on everything from the CCC's blister rust control work to proposed boundary changes. Still, the influence of biologists should not be exaggerated. With so many public works programs underway in the 1930s, the NPS continued to place heavy emphasis on developing the park for recreational purposes.

WILDLIFE RESEARCH

In 1934, the park staff acquired an assistant naturalist, or wildlife technician, named E.A. Kitchin. Like the four new assistant landscape architects and engineers assigned to Mount Rainier, Kitchin was recruited by the NPS using ECW funds. He took up residence at Longmire where he was nominally responsible to the park naturalist, C. Frank Brockman. For the most part, however, Kitchin was allowed to pursue his own research program. Acting Director Arthur E. Demaray outlined a research program for Kitchin covering three main projects. These consisted of investigating the exotic elk population and recommending a policy; surveying the winter range for deer south of the park with a view toward a possible boundary extension; and monitoring the effects of CCC roadside cleanup on wildlife habitat. [1]

Exotic Elk

The elk problem engaged Kitchin's attention first. Another transplant of Yellowstone elk had been made in the Cascade Mountains east of Mount Rainier in 1932. One year later, park rangers reported that elk were ranging into the park near Cowlitz Divide. [2] Just as it had twenty years earlier (see Chapter VI), the introduction of Yellowstone elk raised concerns that these animals were taking over range which ought to be preserved for rehabilitating the native Roosevelt elk. As the Wildlife Division's Ben H. Thompson described the situation, "it is not too late to rectify the damage by some means whereby the Yellowstone elk might be replaced by Roosevelt elk, provided all the factors of the case are known." [3] Roosevelt elk could be obtained from the Olympic Mountains. The reason that this population had not been used for a source of stock before was that their rugged, woodland habitat made them more difficult to capture than the more distant Yellowstone elk. [4]

Kitchin's field work confirmed that elk were using both sides of the park for summer range. Working with the park's chief ranger, Preston Macy, Kitchin devised three alternatives for eliminating the elk: (1) employ agents of the Biological Survey to kill the elk on the elk's winter range outside the park; (2) encourage the State Game Commission to open a season on the elk and permit sport hunters to kill the elk on its winter range; (3) kill the elk on its summer range inside the park, packing the meat out for distribution to welfare agencies. Tomlinson favored the first option even though it would require NPS funds; he thought the last option would likely arouse public protest. The state game director indicated that he would publicly support any of these options provided that the destroyed elk were replaced with Roosevelt elk. [5] This initiative by the Wildlife Division got no further than the planning stage, however, presumably for lack of funds. Tomlinson did not include an item for elk management in either his park budget recommendations or his CCC project proposals.

Winter Range for Deer

Tomlinson and the men of the Wildlife Division also found that their priorities differed in the matter of obtaining additional winter range for deer. During their survey of wildlife conditions in the national parks, Wright, Thompson, and Dixon had characterized Mount Rainier as a classic "mountaintop park"—a park whose boundaries had been too tightly drawn around the principal scenic feature, the mountain. It was the common failing of mountaintop parks that the populations of deer and elk—and the predators that depended on them—ranged in the park's high country during the summer only, and migrated out of the park to the surrounding low country during the winter. Mount Rainier's deer population sometimes suffered heavy losses from sport hunters and poachers when it ranged outside the park's protective boundaries. Kitchin's second assignment was to survey the deer's winter range and recommend boundary changes. [6]

The Wildlife Division had been interested in a south side addition to Mount Rainier ever since Wright, Thompson, and Dixon made their faunal survey of the park in 1930. It was thought that the addition of a strip of land from three to seven miles wide between the present park boundary and the crest of the Sawtooth Range would go far to protect the deer population. [7] Kitchin made a reconnaissance of the area, together with logged-off lands west of the park, and suggested that both areas made ideal winter range for deer. Chief Ranger John M. Davis objected to the idea of bringing logged-off lands into the park. This problem notwithstanding, the Wildlife Division kept the proposal alive through 1935. But Tomlinson ultimately quashed the plan. In Tomlinson's view, the Park Service's major priority in Washington state was to acquire the desired rainforest additions to Mount Olympus National Monument and have that highly-prized area upgraded to a national park; minor adjustments to Mount Rainier National Park should not distract the NPS and Washington conservationists from their main purpose. In making this judgment about conservation politics in Washington state, the superintendent received the full backing of senior NPS officials in Washington, D.C. The Wildlife Division had to let the matter drop. [8]

Monitoring of Roadside Cleanup

In the matter of monitoring roadside cleanup, the Wildlife Division wanted Kitchin to alert his superiors to instances where such activity might be causing excessive damage to the natural resources. Here the NPS was responding to those few, insightful critics who had begun to suggest that emergency conservation work was, contrary to its intended purpose, actually taking a toll on the land. In his instructions to Kitchin, Ben Thompson quoted from a recent article by Aldo Leopold in the Journal of Forestry in which that sage conservationist expressed grave doubts about the CCC:

There was, for example, the road crew cutting a grade along a clay bank so as permanently to roil the troutstream which another crew was improving with dams and shelters; the silvicultural crew felling the "wolf trees" and border shrubbery needed for game food; the roadside-cleanup crew burning all the down oak fuel wood available to the fireplaces being built by the recreation-ground crew; the planting crew setting pines all over the only open clover-patch available to the deer and partridges; the fire-line crew burning up all the hollow snags on a wild-life refuge, or worse yet, felling the gnarled old veterans which were about the only scenic thing along a "scenic road." In short, the ecological and esthetic limitations of "scientific" technology were revealed in all their nakedness. [9]

In another few years the Wilderness Society and other preservationist groups would be headlining their opposition to the CCC's frenetic road and trail development program, but at this early date that criticism was still relatively muted. It is to the Park Service's credit that NPS officials tried early in the ECW program to minimize the kind of mischief that Leopold described. Indeed, Thompson urged Kitchin to do no less than conceptualize the flora and fauna of Mount Rainier as a "complex biological society." Kitchin tried to convey this thought in his lectures to the CCC camps. [10] Helping to instill that new ecological thinking in the service was perhaps the Wildlife Division's most important contribution.

Underscoring its goal of pushing ecological research as a management tool, the Wildlife Division proposed in 1935 to set aside an area of Mount Rainier National Park as a "wilderness research area" or "primitive area." Kitchin and an assistant CCC enrollee surveyed a wedge-shaped area on the north side of the mountain bounded by the Carbon River on the west, Huckleberry Creek on the east, and the park boundary on the north. To give this area greater protection, Kitchin proposed closing the Carbon River Road and the Northern Loop Trail, leaving the Wonderland Trail as the only improved access through the area. [11] George M. Wright, chief of the Wildlife Division, endorsed the plan on January 17, 1936. [12] Over the next several months, Tomlinson exchanged views with the Wildlife Division's Adolph Murie, Victor H. Cahalane, and Lowell Sumner on precise boundaries and on the implications of a "research area" for recreational users. Finally, he objected to the idea outright, suggesting that to establish a specially protected area was, by implication, to throw open the rest of the park to unlimited development. Sumner wrote to Cahalane: "This is the old argument with which we are all familiar, but since it appears that Supt. Tomlinson feels quite strongly on the subject it would seem better for us not to press the matter at this time." [13]

In the final analysis, Tomlinson did not support the Wildlife Division on any of its three major initiatives in Mount Rainier—the Roosevelt elk transplant, the south side boundary addition, or the north side primitive area. And in each case, the superintendent's opposition or lack of support definitely killed the initiative. Yet the Wildlife Division provided expertise on a host of minor questions as they arose, and Kitchin accomplished much important work of a routine nature, such as monitoring CCC projects, inventorying wildlife, and contributing to the Naturalist Division's biological collections and Nature Notes. In doing so, NPS biologists were moving the park administration closer to an ecologically-informed approach to park management. [14]

FORESTRY RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTATION WITH RADIO

NPS forestry had roots in the utilitarian school of silviculture. During the New Deal, NPS forestry continued to emphasize the protection of green timber from wildfire, disease, and other infestations. Throughout the Park Service's extensive restructuring in the 1930s, Albright and Cammerer kept the service's Branch of Forestry separate from the naturalist or interpretive branch of the organization. NPS administrators still viewed forest protection as primarily a ranger activity. [15] Nevertheless, the growing emphasis on ecology occasionally brought the two separate spheres together, as occurred in the case of blister rust control in Stevens Canyon when it was discovered that the white pines were being killed by porcupines as well as the forest-tree disease. What to do about blister rust (and the porcupines) was one significant area of forest-related research in Mount Rainier in the 1930s; the other was experimentation with radio communications in fire suppression.

As described in Chapter VII, blister rust had been discovered in Mount Rainier National Park in 1928. Eradication of the host ribes bushes began in a white pine stand near Longmire in 1930. Two years later, the main blister rust control effort shifted to the Muddy Fork-Stevens Canyon area, where it was carried on by CCC labor after 1933. After four seasons of work in this section, the trees seemed to be dying faster than the CCC crews could eradicate the ribes bushes. The density of ribes bushes, steep topography, and a continual diversion of funds to other CCC projects owing to "the mild interest taken in this work by the resident park staff" conspired to undermine the blister rust control's effectiveness. Or so it seemed. In 1936, it was suggested that the work be discontinued. [16]

As the NPS assessed the situation further, another ecological factor came into play. Individual white pines that seemed large enough to fight off an attack of blister rust were being killed by another assailant—either the porcupine or the Mount Rainier mountain beaver. Now the choices were more complicated: abandon the ribes eradication and risk allowing the blister rust to come back, or continue the ribes eradication and risk the possibility that the white pines would simply succumb to the rodent instead, or identify the offending rodent and attempt to control it as well as the blister rust. At this point, two wildlife technicians, the park naturalist, and a plant pathologist were brought into the investigation to determine which animal was feeding on the bark at the base of the trees, and what to do about it. As the NPS's consulting plant pathologist, Emilio P. Meinecke, observed:

It is highly important to know whether we have to deal with one animal or two, and whether an eventual control will have to be directed against an ecologically interesting species like the Mt. Rainier Mountain beaver which is strictly confined to Mt. Rainier, or to a far more common one like the porcupine which was not known to exist in the Park until 18 months ago and therefore cannot be regarded as belonging to the native and characteristic fauna of the Park. [17]

In the end, the biologists offered no definitive answers but counselled restraint. After a field study in the spring, Kitchin and Brockman concluded that the barking was the work of the yellow-haired porcupine, but found that the phenomenon had been occurring for several years. [18] When officials in the Branch of Forestry proposed the use of a poison, ammonium thiocyanate, to attack the blister rust problem more aggressively, officials in the Wildlife Division objected. The circumstances in Stevens Canyon, they insisted, did not warrant "making an exception to the established National Park Service policy against the use of poison for control work." [19]

Meanwhile, the Mount Rainier park staff was pioneering the use of radios in forest protection work. This investigation seems to have been started solely through the initiative of Park Engineer R.D. Waterhouse. Waterhouse began his radio tests in 1928, carrying an 80-pound "portable" radio into the backcountry, testing its range for voice and telegraph communications, and demonstrating the new technology's utility for fire protection. He soon had the support of Tomlinson and Chief Engineer Kittredge, and by 1932 he was also getting help from the University of Washington and the Westinghouse Company's research department. With the advent of the New Deal, Tomlinson regularly assigned CCC enrollees to assist Waterhouse with his radio experiments. [20]

Experimentation with radio sets paralleled another important development in fire protection: lookouts. Permanent lookout buildings appeared in the national forests in the 1920s, but their usefulness was limited at first by the necessity for telephone links between lookouts and standby fire crews. As the number of lookouts proliferated, the Forest Service began its own experimentation with radio in the hope of installing radios in lookouts. Waterhouse cooperated with his counterparts in the national forests adjacent to Mount Rainier, but it soon became clear that the two agencies had somewhat different objectives: while the Forest Service wanted to establish radio communications for its lookout system, the Park Service, not having any lookouts, was interested in portable radio sets that could be used on patrol or at the scene of a fire. Furthermore, the Forest Service emphasized range for coded messages, the Park Service wanted clarity for voice transmissions. [21] As it turned out, the national park was only a step behind the national forests in developing a lookout system of its own. In the summer of 1932, the NPS built four lookouts at Gobbler's Knob, Windy Knoll, Shiner Peak, and Tolmie Peak. It added two more at Mount Fremont and Crystal Mountain in 1934. [22]

|

| Artist's rendition office dispatchers. The scene was used in an exhibit in Ohanapecosh Forest House. (Photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

As other national parks instituted a more aggressive system of fire protection in the early 1930s, NPS officials looked to Mount Rainier National Park for advice in the procurement and use of radio equipment. [23] One report, written for general circulation in the service, described two types of radio sets which had been "developed, tried out and accepted for use by the Forest Service and in Mount Rainier National Park." One was a portable set weighing ten pounds which could transmit and receive up to forty miles; the other was a semi-portable set approximately eighteen inches square, weighing sixty pounds, with a range of about one hundred miles. This report went on to recommend that the technology for radio communication with voice transmission was now sufficiently reliable to be adopted for use by fire-fighting crews, fire lookouts, construction camps, district ranger headquarters within the park, and headquarters. [24]

Despite the cumbersome size and expense of early radios, Tomlinson moved quickly to adopt radio communications in the park. Radios were installed at all district ranger stations in 1933 and two lookouts were equipped with portable radio sets to augment telephone service. The superintendent commented, "The establishment of radio service in the park has been a most valuable addition to park administration and protection work during the winter months when telephone communication is cut off with outlying districts." [25] In 1940, park rangers adopted the use of portable radios in patrol cars. [26] The park administration's use of radio in this era represented innovative, pioneering work. Radio technology improved dramatically during World War II, and radio communications became much more common in the postwar years. [27]

GLACIER STUDIES

Beginning in the early 1920s, the park naturalist made yearly measurements of glacial recession in Mount Rainier. By 1933, the Naturalist Department was conducting yearly glacial recession surveys on the Nisqually, Paradise, Carbon, South Tahoma, and Emmons glaciers, some in cooperation with the city of Tacoma and the U.S. Geological Survey. The primary purpose of these surveys was to contribute to the science of glaciology. Another purpose was to monitor the tremendous forces of nature that made Mount Rainier not only an interesting place but a potentially hazardous one, too.

One of the most destructive natural events in the park up to this time occurred on October 14, 1932, when an ice dam which had formed on top of the Nisqually Glacier burst, sending a wall of water almost thirty feet high over the snout of the glacier and down the Nisqually river bar. The sudden flood smashed into the Nisqually Bridge, took out the center span, and carried it almost in one piece about one-half mile down the river. It was the park's first experience with a glacial outburst flood. Various explanations for the phenomenon were proposed, but nothing could be deduced with certainty from the single experience. [28]

Whenever a glacial outburst flood or other unusual phenomenon occurred in the park it was the Naturalist Department's responsibility to document it. He hoped that correlations between glacial activity and volcanic activity would someday provide the park administration with part of an early warning system for coping with an imminent volcanic eruption.

THE INTERPRETIVE PROGRAM

Mount Rainier's interpretive program in the 1930s built upon foundations laid in the 1920s. Guided nature walks, campfire talks, lectures in the community buildings at Longmire and Paradise, museum development, and scientific research remained the staples of the program. C. Frank Brockman became Mount Rainier's second park naturalist in 1928 and held that position until 1941. Brockman oversaw a growing staff of seasonal ranger-naturalists (from three in 1928 to nine in 1940), and supervised significant improvements in the park's museums. He produced the park's first museum prospectus in 1939.

The naturalist department passed a critical test in 1933. For some years the RNPC's guide department had complained about unfair competition from the free nature walks led by ranger-naturalists. Tomlinson acknowledged that the interpretive program was taking some business away from the guide department, and he and Brockman made several attempts to work out a cooperative plan with the company so that the two programs would not overlap and compete. In the summer of 1933, the company agreed to let ranger-naturalists give public lectures in the Community House at Paradise and accepted the Naturalist Department's plans to offer longer nature walks. But as the RNPC's patronage dwindled, company guides became increasingly critical of the ranger-naturalist activities. In August, the RNPC guide department began giving rival lectures in the lobby of the Paradise Inn, where it plugged its own guided trips while denigrating those offered by the NPS. Tomlinson reacted by suspending the naturalist program at Paradise "in order to make a test of what visitors really want." Hundreds of visitor complaints quickly affirmed the public's desire for an interpretive program. Harold C. Bryant, chief of the Branch of Research and Education, inspected the park at the end of August and made suggestions for further separation of the two services. Henceforth, the RNPC's guide department would specialize in summit climbs, glacier trips, and trail rides. As a gesture of good will, the guides were given a five-minute spot during the ranger-naturalists' evening lectures with which to publicize their activities. [29]

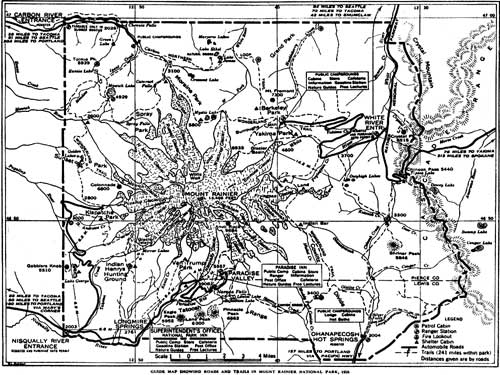

|

| Guide Map for park visitors, 1938. |

The growing popularity of the lecture program was quite impressive. In 1933, Brockman and his staff delivered 196 lectures. These lectures drew an estimated 16,092 people, an average of eighty people for each talk. During the off-season, Brockman gave lectures at schools, chambers of commerce, and other public places in the region. Brockman's lectures outside the park attracted audiences of several hundred people each. [30]

The ranger-naturalists made most contacts with park visitors as the latter circulated through the Longmire Museum or past the floral exhibits and relief model in the Community House at Paradise. Whereas fewer than two percent of park visitors went on ranger-led nature walks, and less than ten percent attended lectures, a solid majority entered the museums. These public contacts in the museum, though brief, allowed the ranger-naturalists to dispense information and perhaps equally important, to personalize the visitor's impression of the park administration. Moreover, museum displays appeared to be the Naturalist Department's most effective venue for conveying interesting information to the visitor which would enhance his or her enjoyment of the park.

Brockman's 47-page museum prospectus provides a clear picture of what the Naturalist Department deemed to be Mount Rainier's most educational and inspirational features in the 1930s. Brockman proposed that the park should eventually have four museums located at Longmire, Paradise, Sunrise, and Ohanapecosh, each with a different focus in keeping with its immediate environs. Thus, the Ohanapecosh museum would tell the story of the lowland forests, the Sunrise museum would tell the geologic story of Mount Rainier, the Longmire Museum would offer biological exhibits together with a minor emphasis on the history and ethnology of the area, and the Paradise museum would focus on "inter-relationships." Brockman's concept for the Paradise museum was the most original, and exemplified the early influence of ecological thought on NPS interpretation. He elaborated:

This museum will explain, in dramatic fashion, the manner in which all features of interest in Mt. Rainier National Park (geology, botany, zoology, and human relationships) are inter-related, correlated and dependent upon one another. It will interpret the scenic beauty and the various features of natural history of which this scenery is composed not as separate units but as a single entity. The motif of the museum, then, will be [the] inter-relationship of all things in nature as exemplified in Mt. Rainier National Park. It will serve as an explanation of how the varied interests in this area bear a definite relationship to one another to bring about a complete interesting and inspiring picture. All exhibits, whether geological or biological, will be definitely aligned with this theme. [31]

Brockman suggested that the Paradise museum would address, among other things, the unintended effects of visitor use on nature in a national park. In planning this particular display, Brockman anticipated the Park Service's vigorous effort many years later to educate the public about the need to stay on designated trails. He described his proposed exhibit on "human relationships" this way:

This feature, because of the great popularity of the national parks and the many complications that arise from such interest, should be given some consideration in order to effect a better understanding on the part of the public as to many of the administrative problems of the park and their relation to certain of our rules and regulations. This should develop a better co-operative spirit. It involves the problem of modifying natural conditions by fire, destruction of plants, by heavy concentration of people, feeding of animals, etc. It also enables one to discuss the relations of human beings, particularly the early [I]ndians, with their interest in or fear of the mountain, their use of plants as food, and various materials for artifacts characteristic of the region. [32]

One can only assume that Brockman was already noting the effects of large numbers of park visitors on Mount Rainier's most accessible alpine meadows. More than twenty years later, while working as a professor of forestry at the University of Washington, he would contract with the NPS to conduct specialized research on meadow rehabilitation around Paradise and Tipsoo Lakes (Chapter XVII).

Although the full scope of Brockman's museum prospectus would not be realized until the Mission 66 period, emergency relief funds paid for considerable expansion and improvement of museum facilities in the 1930s. By 1935, the Naturalist Department was managing small museums at Longmire, Paradise, and Sunrise, and the superintendent was boasting that the park's naturalist program was of "a professional caliber." [33] In 1939, a CCC crew erected a temporary museum building at Ohanapecosh from scrap lumber as it dismantled its own CCC camp buildings. The building would serve as a museum until 1964. [34]

After Brockman left the NPS, he went on to become a leading scholar of outdoor recreation policy and management. In 1978, he published an article in the Journal of Forest History on "Park Naturalists and the Evolution of National Park Service Interpretation through World War II." He described his own efforts in Mount Rainier and the efforts of his contemporaries as truly pioneering work, for early park naturalists were faced with inadequate research, a lack of unified objectives or planning, and minimal financial support. The gradual improvement of the interpretive program in these years, he wrote, "resulted from the interest, efforts, and ingenuity of early workers who persisted, often at personal expense and at sacrifice of personal time, despite criticism and even ridicule." [35]

No doubt an important part of the interpretive program's development in these years was its struggle for credibility. Brockman's own comments on the dubious status of the NPS interpretive program are interesting, though it is unclear how directly the comments pertained to his situation in Mount Rainier National Park. In his article on the evolution of NPS interpretation, Brockman recalled that while ranger-naturalists generally received many accolades from the visiting public, they seldom received much respect from the science academy, which questioned (often with good reason) the scientific credentials of park naturalists. At the same time, the ranger-naturalists sometimes did not fit in with the rest of the park staff. Many ranger-naturalists were teachers who worked in the park during their summer vacations and the permanent rangers often belittled them by calling them "nature fakers," "posy pickers," or "Sunday supplement scientists." [36]

Even Secretary of the Interior Ickes complained that Park Service interpretation could be superficial. He thought that museums simply did not belong in national parks, and that scientific research by park staff was a waste of effort. Worse yet, Ickes maintained, ranger-naturalists too often burdened the visitor with heaps of disconnected facts. "Nothing makes me want to commit murder so much as to have someone break in on a reverential contemplation of nature in which I may be indulging by giving me a lot of statistical or descriptive information relating to what I am looking at," Ickes once fumed. [37] With the Secretary of the Interior expressing thoughts like these, it was no wonder that some park naturalists felt a little insecure about their work.

Brockman, however, proved to be one of the most talented park naturalists in the service. During the winter of 1935-36, Brockman was granted leave after receiving the first of several scholarships awarded to NPS employees for graduate study at Yale University's School of Forestry. [38] Brockman founded the Mount Rainier Natural History Association in 1939, and published his book, The Story of Mount Rainier National Park, the following year. In March 1941, he was promoted to park naturalist at Yosemite, and less than two weeks later Howard R. Stagner took his place at Mount Rainier. [39]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap12.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000