|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART FIVE: CONTENTIOUS YEARS, 1945-1965 |

XVI. MISSION 66 FOR MOUNT RAINIER

INTRODUCTION

Mount Rainier National Park served as the pilot model for the two most significant planning efforts in the history of the national park system. Mount Rainier's role in the development of the master plan concept at the end of the 1920s was discussed in Chapter IX. In a reprise of that role nearly thirty years later, Mount Rainier figured as the first national park to have a development plan under the Mission 66 program of 1956-66. This was no accident. The park's proximity to a major metropolitan area and its location within a fast-growing region of the country made it a bellwether of changing public use patterns throughout the national park system. The three salient trends in national park visitation during the first fifty years of the Park Service—greater use of private automobiles, shorter stays, and growing use overall—each manifested itself early in Mount Rainier National Park. The first national park to admit automobiles, Mount Rainier continued to signal new management concerns for other national parks. Over the years, these management concerns included the demand for free public campgrounds, plummeting per capita revenues for the concession which accompanied the shift from overnight to day use, and problems with overcrowding. Since many of the problems that arose from changing patterns of visitor use needed attention in Mount Rainier before they did in other parks, it was logical that Mount Rainier should twice be a model for planning.

Director Conrad L. Wirth conceived of Mission 66 as a means of summoning administration and congressional support for massive federal investment in the national parks. Instead of going to the Bureau of the Budget and Congress for development funds in two- and three-year driblets, Wirth's idea was to submit a comprehensive plan for the renovation of the national park system over a ten-year span. The completion of the program in 1966 would coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service.

Wirth was helped in this endeavor by individuals and organizations in the conservation movement whose writings in the mid-1950s brought about a heightened public awareness of the state of the parks. For example, Bernard DeVoto's scathing article in Harper's Monthly, "Let's Close Our National Parks," described the decaying infrastructure and demoralizing working conditions in the national parks, and an article in Reader's Digest by Charles Stevenson, titled "The Shocking Truth About Our National Parks," warned prospective visitors of the unsanitary, even slumlike conditions that were typical of the hotels and campgrounds. Closer to Mount Rainier, The Mountaineers added their voice to this rising chorus of protest. Addressing the director of the Bureau of the Budget, the president of The Mountaineers wrote:

Our investigations of the matter show that the Parks are being placed on a stand-by basis in this time of national emergency. We feel that this is a false economy which will be more burdonsome [sic] in the years to come. Besides, the attendance in these parks, even though we have the emergency, have been increasing at an alarming rate. Over 100% in the last fourteen years. [1]

First and foremost, then, Wirth persuaded President Eisenhower and the key committees in Congress to support Mission 66 because it would rectify nearly fifteen years of neglect resulting from budget cutbacks during World War II and the Korean War; it would restore the parks to a condition that would satisfy the growing millions of Americans who used them each year.

Wirth also conceived of Mission 66 as an opportunity to rethink concepts of national park design. Like the master planning which the NPS undertook in the late 1920s, Mission 66 sought to address underlying problems in park design which stemmed from changing visitor use patterns. As Wirth remembered his instructions to his staff years later in his book, Parks, Politics, and the People, the Mission 66 staff and steering committee were to question any elements of national park design that they thought had outlived their usefulness.

Nothing was to be sacred, except the ultimate purpose to be served. Men, method, and time-honored practices were to be accorded no vested deference. Old traditions seem to have determined standards far beyond their time; for instance, the distance a stagecoach could travel in a day seemed to have been a controlling factor in establishing public facilities in some parks. [2]

Like the earlier master planning effort, Mission 66 sought to provide the right mix and distribution of visitor services to alleviate crowding while satisfying public demand. If the first effort at master planning in the 1920s had followed the triumph of the private automobile over the old combination of railroad and stage in national park use, the new effort at master planning recognized the primacy of the day-use visitor over the overnight visitor. In Mount Rainier National Park, day users now accounted for fully 92 percent of park visitors; overnight campers amounted to 5 percent of the total while hotel visitors amounted to a mere 3 percent. [3]

Visitor use of Mount Rainier differed from most national parks in one important particular and that was its problematical winter season. Winter use of Mount Rainier had grown remarkably during the 1930s but had waned since 1946. In the early 1950s, park planners concluded that adverse weather conditions made Paradise less desirable for downhill skiing than other, newly developed Cascade locations, but local business interests prevailed on the NPS to keep the area open for winter use anyway. By 1954, the NIPS had adopted a compromise plan that would develop Paradise for day use but not overnight use during the winter. The future of overnight lodging in the Paradise area during the summer was left for further study. That further study, as it turned out, put Mount Rainier in a position to serve as a pilot park for the Mission 66 program. [4]

In February 1955, Wirth created a seven-member Mission 66 committee and a seven-member steering committee comprised of the supervisors of the people on the main committee. Mount Rainier's former park naturalist, Howard Stagner, sat on the Mission 66 committee; and the principal author of Mount Rainier's original master plan, Thomas C. Vint, sat on the steering committee. Wirth wanted the report on Mission 66 drafted and ready to submit to the President and Congress within one year. In the course of that year, the Mission 66 committee devoted more study to Mount Rainier than to any other national park. [5] The Mount Rainier development plan was the first to be completed by the Mission 66 staff after the Mission 66 program was approved by President Eisenhower and submitted to Congress on February 2, 1956.

Ironically, when Wirth unveiled the Mission 66 plan for Mount Rainier National Park on March 15, 1956, it plunged the park into controversy once more. The twin objectives of Mission 66 were (1) to upgrade and expand facilities for the rising tide of day-use visitors, and (2) to revamp visitor circulation in order to alleviate crowding. In Mount Rainier National Park these broadscale objectives translated into one overall solution: move all overnight guest and administrative facilities to lower elevations, if not entirely out of the park. After the recent controversies over the concession contract, government acquisition of the RNPC's buildings, and non-authorization of a permanent chair lift at Paradise, the plan appeared to be counter to everything that business interests and the state's political leaders had been advocating during the past decade. Ignoring the fact that Mission 66 promised to lavish $10 million on new development in the park, business leaders joined state politicians in denouncing the plan. They focused narrowly on the proposal to relocate overnight accommodations away from Paradise. Elsewhere in the nation Mission 66 was well-received by the public; in Washington state it met with opposition and rancor.

This chapter focuses on what Mission 66 actually accomplished for Mount Rainier National Park in terms of its twin goals of updating the physical plant and improving the circulation of visitors. The first section looks at the outcome of Mission 66 for overnight lodging. Since overnight lodging lay at the heart of the controversy, this section also treats the politics of the Mission 66 program, which had repercussions for other elements of the program in Mount Rainier as well. The second section discusses the plan to move park headquarters to a lower elevation, from Longmire to a site outside the park near Ashford. In the third and fourth sections, road and campground development are summarized respectively. The fifth section looks at changes in the interpretive program in this era, with particular reference to the role of visitor centers and wayside exhibits.

OVERNIGHT LODGING FACILITIES

On March 15, 1956, the Park Service announced that the Mission 66 plan for Mount Rainier called for more than $10 million in development over the next ten years in order to meet the needs of the one million visitors expected in the park annually by 1966. Of this amount, approximately $4.3 million would be for road development, $2.7 million for transfer of park headquarters to a new site, and $3.8 million for visitor use facilities, including visitor centers, campgrounds, and picnic areas. Overnight accommodations, according to the Park Service's first press release on the subject, would eventually be relocated to "scenic sites close to the park's borders." [6]

The press release quoted Wirth as saying that the present RNPC concession contract would be renewed on an annual basis, if necessary, until privately-owned and operated lodging facilities were available at new locations. "In seeking the most practical and desirable solutions to the problem of overnight accommodations," Wirth explained, "all the facts indicated that such facilities should be located at lower elevations. The normal development of motels along the approaches to the park can be expected to take care of much of the need, but we shall continue to seek the best possible place, in or out of the park, for development of new accommodation centers." [7] The $3.8 million apportioned for visitor use facilities would go primarily to day-use facilities. This was a reasonable allocation in light of the fact that 92 percent of park visitors did not stay overnight.

Wirth anticipated that the plan would meet with objection from Washington state business interests. When he informed the RNPC's Paul Sceva of the plan, Sceva immediately raised such strong reservations that Wirth found it necessary to request Sceva's confidence until the plan was made public, and more, to order Superintendent Macy and all park staff to refrain from any discussion of the plan with Sceva until they were instructed differently. Sceva denounced Wirth' s directive as a "gag order" and fumed about it six months later to a committee of Congress. Sceva also criticized the NPS for not seeking the RNPC's input sooner in view of the company's forty years of experience as the park concession. [8] Wirth retorted that Sceva had acted irresponsibly by leaking information to selected pro-development groups. Moreover, the RNPC had already explained its position on overnight accommodations at Paradise during the recent negotiations over its contract concession. Indeed, the NPS itself had been on record in favor of moving overnight accommodations to lower elevations for more than a decade as the problem had been under study since World War II.

Alternatives to Paradise and Sunrise

The concept of moving overnight accommodations out of Paradise and Sunrise to lower elevations had three sources, all of them originating in the period 1942-46. The first in time, if not importance, was the decision in 1943 to evaluate alternative sites for the park headquarters. While the paramount consideration in this case was the danger of flooding by the Nisqually River, Longmire's 2,000-foot elevation and the dark and damp conditions prevailing through the winter at the base of Mount Rainier were also cited as reasons for relocating the headquarters to a lower elevation in or outside the park. This proposal was under consideration all the time that NPS officials deliberated over the future of visitor facilities at Paradise.

The second precedent for this important concept was the removal of the 425 housekeeping cabins located at Paradise and Sunrise in 1943-44. The RNPC maintained that the primary reason it got rid of the cabins was that they were obsolete; park visitors wanted better accommodations. But company officials acknowledged that the drafty, unheated cabins had never proven popular with the public and that the cabins were structurally unfit to withstand the winters. Several had collapsed under snowloads, and maintenance costs for all the others were high. When the RNPC sold the cabins for emergency housing during the war and had them removed, RNPC and NPS officials agreed that the cabins were a failure and would not be replaced, at least at such high elevations. [9] After the war, Superintendent Preston discussed with officials of the neighboring Snoqualmie National Forest the need for cabin developments at lower elevations, perhaps along the White River outside the northeast corner of the park. Although nothing definite came from the talks, it was the first instance of the park administration seeking to develop visitor accommodations outside the park. [10]

The third and most important source for this concept was the pressure which state politicians and the tourist industry brought to bear on the NPS to develop new all-year visitor facilities. At the end of World War II, Governor Mon C. Wallgren accorded high priority to the development of Washington state's tourist industry. Tourist industry representatives contended that Mount Rainier National Park ranked as the premier tourist attraction in the Pacific Northwest. Overnight accommodations must figure prominently in the postwar development plans for the park, they insisted. Each tourist turned away from Mount Rainier for lack of hotel space constituted a reduction in the state's tourist industry. It was incumbent on the NPS to maximize the national park's vacation potential. Specifically, the governor and the tourist industry demanded the development of new visitor facilities at Paradise. [11]

Everything that the NPS had learned from its experience with the RNPC argued against such a development. Even if day-use facilities and a range of overnight accommodations were combined into one building, and the building were given a vertical design in order to minimize the snowload, and it were made of concrete to ensure fire safety—even then, NPS architects cautioned, it would cost about $2 million. Surely there were better areas where $2 million could be spent on new visitor facilities in Mount Rainier National Park. Thus did state politicians and the tourist industry provide the third source of inspiration for moving visitor accommodations to a lower elevation. In 1946, NPS planners began to scour the park for alternative sites for a $2 million visitor facility.

Two alternative sites emerged as favorites, one for Sunrise and one for Paradise. On the east side, the favored development site was found along the lower portion of Crystal Creek. Consisting of several acres on either side of the creek, the site was located a short distance off the Mather Memorial Parkway inside the northeast corner of the park. With some clearing of trees it would afford a fine view of Mount Rainier and it was convenient to Sunrise, the Tipsoo Lake-Cayuse Pass area, and the proposed Corral Pass ski area northeast of the park. On the south side, NPS planners considered an area along Kautz Creek south of the park road, but ended up in favor of a site on Skate Creek, just outside the boundary of the park on the south side of the Nisqually River. The site would be accessed by a new state road between Ashford and Packwood (Skate Creek Road) and a short connecting road to Longmire. [12]

By the time these two sites were included in Mission 66 for Mount Rainier, the Park Service had determined that private capital should be sought to develop them. Apparently NPS planners believed that the gentler climatic conditions found at these lower elevations, together with the growing amount of park visitation, would induce private capital to invest in overnight accommodations at the edges of the park if not in its center. Ironically, they compared their vision for Mount Rainier to the situation in Great Smoky Mountains. There, virtually all concession services were furnished by the community of Gatlinburg, Tennessee—a place that would become so overrun by the tourist industry in the 1960s and 1970s that it would stand as the most notorious example in the nation of a national park gateway town. [13]

The plan struck developers as odd and inconsistent. Although the Secretary of the Interior's concession policy statement of 1950 had endorsed the idea of government ownership of visitor facilities, the NPS now seemed to be going back to Mather's idea of placing greater reliance on private capital for visitor accommodations. The Mission 66 plan declared: "It is a long-standing National Park policy—a policy in which Congress has repeatedly manifested its concurrence—that the construction and operation of concessions are proper functions of private enterprise." [14] This was somewhat disingenuous in view of the recent act of Congress which had authorized the government to purchase the RNPC's buildings.

Neither the Crystal Creek site nor the Skate Creek site was ever developed. Washington business interests and politicians and Washington's congressional delegation rejected the very concept of moving overnight accommodations to lower elevations in or outside the park. This crucial part of Mission 66 for Mount Rainier was eliminated, and the Park Service was forced to go back to the drawing board and explain how it would redevelop the Paradise area for overnight use.

Paradise Reconsidered

Senators Magnuson and Jackson played a key role in amending Mission 66 for Mount Rainier. In March 1956, the two senators wrote a joint letter to Senator James Murray, chairman of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, questioning the wisdom of the development plan and requesting a hearing. The two Washington senators subsequently grilled Director Wirth at two hearings, the first held on Capitol Hill, the second in Tacoma. At the second hearing, held in October 1956, David Brower of the Sierra Club tried to educate the senators to a central tenet of the NPS 's opposition to overnight accommodations at Paradise: that the hotel would draw so many people as to exceed the "carrying capacity" of the area. But this unfamiliar concept sailed over the heads of the senators. Not satisfied with the work of the Park Service's own Mission 66 committee, the senators directed Wirth to make two further studies: one to determine what inducements could be offered to private enterprise to build or operate overnight accommodations at Paradise; the other to present alternative sites and building plans for overnight accommodations, regardless of whether they were built by private or public funds. [15]

The NPS completed the latter report in March 1957. The building design was so odd and incongruous in a national park as to be impossible to consider seriously. Taking into account snowloads, NPS architects proposed a ten-story building that would house all government and hotel operations at Paradise. The first three floors would be used for parking, the fourth floor would be on a level with the average depth of snow in winter and would contain the lobby and dining room. The six floors above this would contain 270 guest rooms, 60 employees' rooms, and an employee dining room. The estimated cost for the building was $5 million. [16] Upon receiving this report, Senator Jackson wrote to Wirth, "I am pleased that the report is labelled 'preliminary,' because, frankly, it strikes me that some more feasible plan could be devised than for a 10-story hotel that will lose more than $318,000 a year." [17]

Senator Magnuson, working with House conferees on the House appropriations bill, had an item included in the Senate report directing the Park Service "to complete its studies and make recommendations as to how private enterprise might be encouraged to do the job." Acting on this directive, Senator Jackson invited Laurance S. Rockefeller of Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., to conduct this feasibility study on the Park Service's behalf. [18] Three months later, on October 15, 1957, Wirth agreed to fund such a study by Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc.

The Board of Trustees of Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., appointed a committee to oversee the study. Former director of the NPS Horace M. Albright was appointed chairman. Other committee members were Raymond C. Lillie, vice president and general manager of the Grand Teton Lodge Company; Eldridge T. Spencer, an architect who had designed visitor accommodations in Yosemite, Grand Teton, and other national park areas; and Allan C. George, a partner in the hotel consulting firm of Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company. Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company performed a market analysis of overnight visitor demand in Mount Rainier National Park in conjunction with Jackson Hole Preserve's feasibility study. [19]

In the course of several visits to Mount Rainier during different seasons of the year and with the benefit of many interviews with prominent businessmen, civic leaders, and conservationists in the region, Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., found that there were "no completely satisfactory solutions" to the problem of overnight accommodations in Mount Rainier National Park. "If there had never been any development," Rockefeller stated to Jackson, "the problems would seem much simpler." Instead, the adverse climate conditions at Paradise had to be weighed alongside the tradition of visitor accommodations, the location of Paradise relative to the existing road system, and the aim of Mission 66 to develop extensive day-use facilities in the park.

In January 1959, Jackson Hole Preserve gave qualified support to the proposal to build new overnight accommodations at Paradise:

Our conclusions without question support the view of Director Wirth of the National Park Service that overnight facilities in Mount Rainier National Park cannot be operated on a profitable basis if interest and depreciation on the initial investment are taken into consideration. On the other hand, our Trustees, with one exception, feel that if a way can be found to finance the construction of modern and adequate facilities at Mount Rainier, the most desirable site appears to be in the Paradise area. We believe that it is practical to construct facilities in that area, and that such facilities so located might more satisfactorily serve the public need than in any other location. We further believe that the idea of coordinating National Park Service plans for day use facilities with overnight accommodations in the Paradise area, all to be operated by one concessionaire, has merit. [20]

As might be expected from such an equivocal finding, Jackson Hole Preserve's report was interpreted in opposite ways. To Acting Secretary of the Interior Roger Ernst, the report supported the Park Service's longstanding contention that a lodge at high elevation in Mount Rainier was not economically feasible. Moreover, Ernst pointed out, the subsidiary report by Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company overlooked the imperative to protect basic national park values. Jackson Hole Preserve had provided no compelling reasons for building a lodge at government expense, and absent any legislation by Congress the NPS had no intention of undertaking such a project. [21]

But Washington's congressional delegation argued that Jackson Hole Preserve had endorsed the idea of a government-subsidized hotel development. In the spring of 1960, Representative Tollefson and Senators Magnuson and Jackson introduced House Joint Resolution 774 and Senate Joint Resolution 193, "To Authorize the Construction of a Hotel and Related Facilities in Mount Rainier National Park," and when the joint resolutions failed the first time the three men reintroduced them the following year. Representative Tollefson claimed that 85 percent of Washington residents favored overnight accommodations at Paradise, as did nearly every daily newspaper in the state. According to Tollefson, the Rockefeller Foundation endorsed this view. [22]

Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall requested, through the Office of the Solicitor, a report by the NPS director on the House and Senate joint resolutions. Wirth stood firm. He reiterated what he had said (and what David Brower had described more pointedly) in the congressional hearings, that the development of overnight facilities at Paradise would jeopardize basic park values by bringing too many people into a fragile area. "It is not simply a matter of finding space for a hotel, but of finding adequate space needed for a facility which in itself becomes a magnet in holding people in the area beyond the time devoted to scenic enjoyment and recreational pursuits." He also reemphasized the economic argument that a government subsidy would not only be necessary, but would need to be large. Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company had estimated that a 300-room capacity hotel would cost $6.9 million. Wirth declared that this estimate was conservative, and when the rebuilding of water and sewer systems were taken into account, the cost would be at least $12 million. [23] Secretary Udall personally inspected Paradise that summer, backed up the NPS director, and reported unfavorably on the joint resolutions to Congress.

Diversion: The Crystal Creek Site Proposal

But Udall was too astute a politician to try to let the matter simply drop. He offered a consolation prize to the Washington delegation: the Department of the Interior would cooperate with the Department of Agriculture in a joint survey of high elevation sites on the northeast side of the park where snowfall was less. Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson explained that the goal of the survey was to "provide a long-needed first-class mountain inn so located as to save Mount Rainier's wilderness and snow areas without disturbing its natural beauty." [24] In October 1961, the Department of the Interior announced that a tentative site for all-year overnight accommodations had been selected. [25]

The Interior Department's Director of Information James N. Faber made the announcement at a closed meeting in Seattle attended by Magnuson, Jackson, and a dozen public officials and businessmen from Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia. The site was on Crystal Creek, proposed five years earlier in the original Mission 66 development plan; it was not at a high elevation though it was inside the park. Now, however, it could be developed in conjunction with the new Crystal Mountain ski resort in Snoqualmie National Forest—a federally-subsidized hotel in the park, and a privately-financed ski resort and chair lift on nearby Crystal Mountain in the national forest. Business representatives said that the proposal was a trial balloon to test whether local public opinion would settle for something more modest or continue to demand new overnight accommodations at Paradise, They also thought the site was flawed; located deep in the forest, hotel guests would find nothing to do there. Faber insisted that the Crystal Creek proposal was the best plan that Washington residents could expect to get from Congress. As a reporter for the Tacoma News Tribune interpreted Faber's announcement, "It appears it is Crystal Creek or nothing—all locked up, signed, sealed and delivered." [26]

But Washington's politicians successfully reopened the issue. In November, Governor Albert D. Rosellini set up a six-member citizens' advisory group to study the problem of overnight accommodations in Mount Rainier National Park. [27] In January, Rosellini suggested that the NPS reconsider the development of a chair lift at Paradise. Even more ominously, he appointed Clayton D. Anderson to the directorship of Washington State's Department of Parks and Recreation. Anderson, a former horse wrangler at Paradise, had already spoken out against the Mission 66 plan to move campgrounds to lower elevations. [28] Out of this fractious debate emerged another political deal: the Department of the Interior and the Washington State Department of Commerce and Economic Development would each contribute $10,000 toward yet another study, this one to consider four sites in the park for development: Paradise, Longmire, Crystal Creek, and Klickitat Creek. [29]

The governor and the Department of the Interior took more than a year to agree on a consultant for the study and finally the contract was awarded to Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company, the consulting firm which had participated in the study by Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., four years earlier. Two members of that firm, Henry Maschal and Richard Raymond, visited the park in May and June, 1963. The firm considered each site from the standpoint of winter and summer use, local natural features, climate, and historical development. The findings by Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company were emphatic. "We do not recommend the construction of any hotel type accommodations within Mount Rainier National Park," the report stated. [30]

Washington state officials were dismayed by the conclusion. [31] At the closed-door briefing on the report, held at the Hilton Inn in Tacoma on August 7, 1963, one state official wanted to know why Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company had made an apparent complete reversal from the Rockefeller report. Maschal replied that the earlier study had looked at the feasibility of overnight accommodations based on the assumption that the government would provide $9 million. The latter study proceeded on no such assumption. [32] Moreover, the Park Service's insistence that visitor facilities must be oriented to the rising tide of day-use visitors had finally made a strong impression. "The very limited areas available for development are and will in the future be increasingly needed for day use facilities and accommodations and for overnight camping," the report stated. "Camping facilities are in this respect favored over hotel type facilities because such camping facilities can be provided in available areas unsuited to hotel sites and because of the appreciably lower cost of facilities and operation per person accommodated." [33]

Conservation groups applauded the study's findings. The findings squared with the position taken by The Mountaineers, that the purposes of the national park would be best served if the significant features of the park were preserved for recreational, educational, and inspirational enjoyment, while overnight accommodations were relocated to less fragile and significant areas of the park. [34] The findings were welcomed by the National Parks Association, which went on record in favor of eliminating overnight accommodations at Paradise at the end of the Paradise Inn's useful life. [35]

Even in the face of the study's negative recommendations, pro-development interests did not give up. The governor's Mount Rainier Study Committee asked the authors of the study, Maschal and Raymond, to include in their final report what they thought could be done with a $2 million appropriation. [36] And before waiting for the final report, Representative Tollefson made a last-ditch effort to get new overnight accommodations at Paradise by introducing House Joint Resolution 685 in the House of Representative on September 5, 1963. The resolution called upon the Congress to donate matching funds for the construction of overnight facilities at Paradise, and it cited the independent study by Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., for support (saying nothing of the adverse finding by Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company). Once again the NPS advised the Secretary of the Interior, through the Department's legislative counsel, to recommend against the adoption of H.J. Res. 685. [37]

|

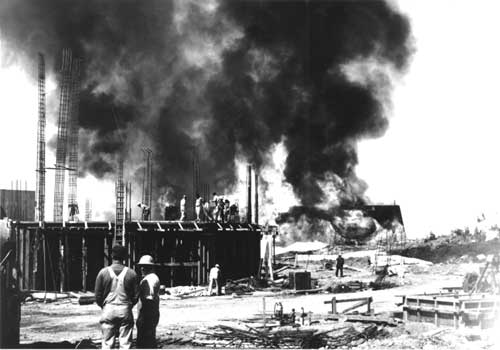

| The Paradise Visitor Center is under construction as Paradise Lodge burns in the background, June 3, 1965. The destruction of Paradise Lodge stirred local sentiment about Mount Rainier's other historic buildings. (Ed Bullard photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

Compromise: The Paradise Visitor Center

Senators Jackson and Magnuson, meanwhile, had set to work on a more promising line of approach for promoting new development. In the early summer of 1963, Senator Jackson made his own inspection of Paradise, Longmire, and the Skate Creek site, and decided that Paradise should be developed for day use only. Whether overnight facilities should be located at Longmire or Skate Creek he could not decide, but now his first priority was to secure funds for a new visitor center at Paradise. The senator may have arrived at this decision out of personal conviction after his tour of the park with Superintendent John Rutter; he may have been impressed by the growing determination of conservationists to resist new, overnight hotel development in the park; or he may have simply decided that a good many of his constituents who used the park would regard half a loaf as better than none. [38] In any case, Jackson obtained Magnuson's help in securing $465,900 for the NPS budget for the 1964 fiscal year as a start toward construction of an all-year day-use building or visitor center at Paradise. The visitor center was to include a restaurant, museum, information center, ski rental shop, and warming hut. [39] Construction of the Paradise Visitor Center began in 1964 and reached completion in 1966. As expected, its eventual cost far exceeded the original allocation. Indeed, the Paradise Visitor Center preempted NPS plans for a new visitor center at Sunrise. [40] At $2 million, it was the most expensive building in the national park system. [41]

The public's response to the new facility was mixed. The building's modern design pleased some and disappointed others. Designed by the two architectural firms of Wimberly, Whisenand, Allison and Tong of Honolulu and McGuire and Muri of Tacoma, the building's round layout and conical roof were supposed to relate the structure to its mountain setting. Other visual design features included "the swooping, bough-like shape of the beams, the branching 'tree' columns, the 'switchback trail' ramps, and the sloped 'cliffs' of the stone base." [42] To many people's way of thinking, however, the building did not harmonize with the landscape in the least. People complained that it looked like a satellite, pagoda, or flying saucer. Its weird, extraterrestrial effect was enhanced when Paradise was shrouded in fog, as was often the case. Or when snow still lay on the ground, people joked that the new visitor center looked like the Seattle Space Needle—up to its neck in snow. And when it became known that Senator Jackson had used his influence to get the Department of the Interior to contract with a Honolulu-based architectural firm to design the building, a legend grew among the park's devotees that the building had been designed for a site in the Hawaiian Islands but had been dumped on Mount Rainier instead. This was not true, however. [43]

|

| The modern design of Paradise Visitor Center met with mixed reactions. (R.L. Lake photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

The public not only felt dubious about what they had gained, they mourned what had been lost. Ironically, the opening of the Paradise Visitor Center in the summer of 1966 coincided not only with the conclusion of Mission 66 but with a burgeoning public sentiment for the preservation of historic buildings and places. The National Historic Preservation Act, which would have profound implications for the Paradise area in years to come, was passed by Congress that same year. It was a sign of the public's growing unease about the pace of new development that the most newsworthy event during the construction of the Paradise Visitor Center occurred on June 3, 1965, when Paradise Lodge was burned to the ground to make room for new parking. No sooner was the building destroyed than NPS officials were having to make assurances that the Paradise Inn would remain standing; the obliterated building was only the more modest and recent of the two hotels at Paradise. [44] To these officials it seemed like only yesterday that the public was agreeing with them that the old buildings had outlived their usefulness; now the public valued the buildings for their age—the older the better.

Congress's approval of funds for the Paradise Visitor Center proved to be one of two crucial decisions that perpetuated Paradise's long-held and perplexing role as a focal point of visitor use in Mount Rainier National Park. The second crucial decision came more than ten years later with the designation of Paradise Inn as an historic building in an historic district (see Chapter XX). The latter decision finally resolved the long public debate over new overnight facilities at Paradise by establishing a third alternative that no one had even bothered to consider during the whole Mission 66 era: to preserve the original Paradise Inn as a charming reminder of the park's early years.

Unfortunately, these two decisions undermined the main organizing principle of Mission 66 for Mount Rainier. That principle was to separate day use from overnight use by relocating key visitor facilities to lower elevations in or outside the park. Jackson's and Magnuson's forceful intervention on behalf of the Mount Rainier development lobby in the 1950s and 1960s had lasting consequences for the pattern of visitor use in the park. The episode stands as one of the best examples in the park's history of how local interests intertwined with Park Service initiatives to reshape the park as a cultural landscape.

RELOCATION OF PARK HEADQUARTERS

As suggested in the previous section, the idea of moving headquarters from Longmire to a new site outside the park was one of the wellsprings of the Mission 66 development plan for Mount Rainier. There were many advantages to be gained by moving headquarters to a lower elevation outside the park. Costs for building maintenance would be lower farther from the base of the mountain where snowfall was lighter. Employee morale would be better if park employees and their families had easier access to schools and other community services located away from the park. Congestion in the confined area around Longmire would be alleviated. Most importantly, headquarters would not be in danger of destruction by an outburst flood or mudflow coming down the Nisqually River. These arguments preceded Mission 66's general proposition that major development sites in Mount Rainier National Park should be located at lower elevations farther from the mountain.

Unlike the plan to relocate overnight accommodations to lower elevations, however, the plan to move headquarters outside the park did not elicit much public debate. Congress balked at the plan simply because of the costs involved. It questioned spending $2.5 million for administrative buildings when the money could be put to visitor facilities instead. [45] For this reason alone, the Park Service's efforts to move headquarters outside the park took some 35 years to bear fruit.

Since the plan to move headquarters was relatively uncontroversial, its chronological development can be sketched briefly. The idea first formed in 1943 and received serious study in 1945-46; it became an integral part of Mission 66 development planning in 1955-56; Congress authorized the purchase of an administrative site, called Tahoma Woods, near Ashford, in 1960; and the new headquarters buildings were completed and occupied in 1976. Relocation of headquarters received low priority because it had low public visibility; therefore, the plan progressed very slowly.

This section examines the four main factors that weighed in the decision to relocate park headquarters: (1) cost efficiency, (2) living conditions, (3) protection of park values around Longmire, and (4) risk assessment of the potential for a natural disaster at Longmire.

A Search for Cost Efficiency

As park planners updated the master plan for Mount Rainier during World War II, they pointed out a need for much new construction at park headquarters. They anticipated that park operations and staffing would grow with the expected boom in visitation after the war, and they noted that many of the existing buildings were obsolete or deteriorated and would need replacing. Yet expansion and rehabilitation of the headquarters area at Longmire posed some problems. The amount of level terrain was limited, the ground was rocky and costly to excavate, and additional forest would have to be cleared. In addition, further flood control work on the Nisqually River would be necessary before the terrain could be safely occupied. All of these cost factors suggested that it might be more efficient to begin with a new headquarters site somewhere else. [46]

Park planners investigated three alternative sites in 1943. These were at the confluence of Kautz Creek and the Nisqually River inside the park, at Nisqually Entrance immediately outside the park, and near the town of Ashford about six miles outside the park. [47] The Kautz Creek site was eliminated after the Kautz Creek flood of 1947, and the Nisqually Entrance site did not have much to recommend it, so the Ashford site emerged as the favorite. In 1951, Director Wirth recommended a site on the Mather Memorial Parkway immediately north of the park, or in the town of Enumclaw. Relocating park headquarters to the east side of the park seemed desirable only if the park's major winter use area was to be on the east side, so that idea was abandoned soon thereafter. [48]

Detailed cost comparisons were made between Longmire and the Ashford site. While river protection revetment at Longmire would cost an estimated $55,000, similar costs would be incurred near Ashford for building an access road and water and sewer systems. Approximately the same number of new buildings were listed in either plan. One important difference was that the Longmire plan called for a new museum building, while the Ashford plan called for a new administration building and conversion of the administration building at Longmire into a museum. The cost comparison made in 1943 ended up with two very similar figures: $668,780 for expanding the Longmire administrative site as compared with $631,750 for developing a new administrative site near Ashford. [49]

The Park Service more than tripled these cost estimates in 1955. Labor and construction costs rose sharply in the postwar era, and the need for employee housing expanded considerably during the decade, too. Once again, the two figures were remarkably close—$2,078,700 as opposed to $2,067,350. The cost of additional residences and equipment storage sheds in the Ashford plan was more than offset by the cheaper construction costs overall due to the milder climate, better soil conditions, smoother terrain, and shorter haul for building materials. Park planners did not venture to make a detailed comparison for operation and maintenance costs, but they offered the following points:

1. The Ashford site was more convenient to local business centers for pickup and delivery of equipment and supplies.

2. The Ashford site was within the fifty-mile zone for office machine repair, thereby allowing the park administration to pay for repairmen to come to the site rather than having to take broken equipment to repair shops in Tacoma or Seattle.

3. The Ashford site was adjacent to a regular distribution line of public power and telephone. Public services to the employee residences would reduce park operation and maintenance costs.

4. Costs of snow removal would be comparatively minor at the Ashford site. With headquarters personnel and their families located at Longmire, it was sometimes necessary to plow the park road early in the morning and again in the afternoon to permit the school bus to get in and out.

5. The milder climate at Ashford would reduce heating costs.

6. Increased travel time for personnel to and from the park would be partially offset by reduced travel time between park headquarters and other points such as Tacoma and Olympia.

In the final Mission 66 prospectus, it was estimated that development of the Ashford site would cost $2,355,700. Acting Secretary of the Interior Roger Ernst approved the plan, as did the Bureau of the Budget. Congress did not question the cost efficiency of the Ashford site as compared with similar headquarters development at Longmire; rather, it questioned spending $2.5 million for buildings which almost all of the visiting public would never see. Was there really a need?

A Need to Improve Living Conditions

When park superintendents submitted their budget estimates, employee housing was usually the thing they least wanted to ask for. Practically everything else in the budget could be justified to Congress either in terms of a public need which visitors could directly perceive, or as a resource which the NPS was charged with protecting. But employee living conditions had no immediate effect on either the public's enjoyment or preservation of national parks, so to apportion more funds for employee housing always required the strongest proofs for Congress. Living conditions generally had to decline to the point that they were demonstrably undermining employee morale before the superintendent could expect to get anything done about it. Yet no superintendent wanted to report that his staff had low morale. The problem of personnel housing placed park superintendents in a Catch-22 situation.

|

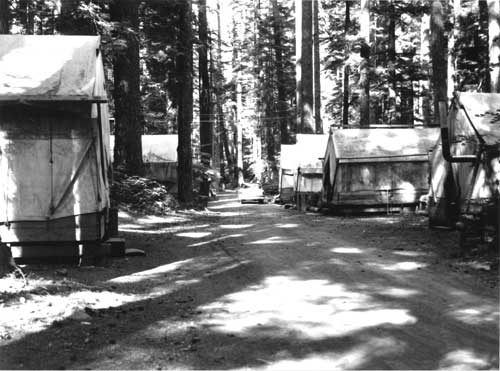

| Seasonal park employees lived in "Tent City" at Ohanapecosh. These housing conditions persisted into the 1960s. (J. Boucher photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

In their 1943 study of the headquarters relocation question, Regional Engineer R.D. Waterhouse and Regional Chief of Planning E.A. Davidson stated that there were twenty-six residential quarters in Longmire. Of these, seven were relatively new and on a par with modern housing standards, ten were sub-standard and in need of replacement, five were fit for summertime use only, and four were unfit even for summertime use. In addition to these poor housing conditions, Longmire residents had to contend with large amounts of snow when their neighbors fifteen miles down the road generally did not, and they had to drive long distances for schools, groceries, and social activities outside the park. Furthermore, Longmire could be an oppressive place to live; the forest setting greatly reduced the amount of light and sunshine. Waterhouse and Davidson concluded, "there is a definite increase in labor efficiency in an area which is free from snow, with consequent savings to the government." [50]

The housing shortage in Longmire became acute as former park employees returned from military service after World War II, some of them accompanied by new families. In 1946, Superintendent Preston suggested to Regional Director Tomlinson that a stopgap solution might be to convert the Longmire Mess Hall into living quarters and to relocate the old CCC mess hall from Paradise to a site near the Longmire Community House and turn it into apartments. [51] Two years later, when no appreciable progress had been made, Preston described the situation as desperate. Tomlinson informed Drury that employee housing at Mount Rainier had been neglected so long as to be mostly a product of "salvaged material, contributed labor and piecemeal throwing together." Preston's report on the situation suggested to Tomlinson "that we can no longer neglect the vital question of housing of our employees—we must place their housing at or near the top of our priority lists." [52]

Ten years after the end of World War II, it only seemed reasonable that Mission 66 for Mount Rainier should carry a large item for rehabilitation of park headquarters—including employee housing—along with funds for road, trail, and campground development and new visitor centers. Indeed, the $2.5 million price tag for relocation of headquarters constituted one fourth of the total Mission 66 program. But NPS officials recognized that it would still be a tough sell to Congress. As if conceding that the various items directly related to visitor use would be given priority, NPS officials consistently buried the $2.5 million item at the back of each Mission 66 development plan. Even then, they eschewed any mention of new employee housing.

There was one exception. An in-house report, drafted in the summer of 1955, provided a frank discussion of the need to improve living conditions for park staff. The report gave seven reasons why employees might prefer living near the Ashford site to living at Longmire. [53]

Park employees who were stationed at headquarters had to wait many years before they were provided with new housing at Tahoma Woods. However, one of the later Mission 66 projects involved the construction of NPS housing units for employees who were stationed on the east side. Located in a secluded site near the Ohanapecosh developed area, the site had many of the advantages that were sought in the site near Ashford. The project took precedence over Tahoma Woods because it was located in rural Lewis County, thereby making it eligible for partial funding under the Accelerated Public Works program.

Protection of Park Values at Longmire

Park planners argued that Longmire must not be permitted to grow much larger because the administrative site itself would detract from the scenic and natural values of the national park. Waterhouse and Davidson declared this unequivocally in their 1943 report. "Growth and expansion of villages within the boundaries of national parks is diametric to principles of preservation as stated in basic park law," they wrote. One particular concern was that the additional clearing of forest needed to expand facilities would be clearly visible from high points such as Ricksecker Point, forming an unsightly hole in an otherwise "practically virgin forest landscape." [54]

Waterhouse and Davidson contended that the "pioneer" period of development at Longmire had passed, and most of the buildings were at the end of their useful life. Rather than rebuild them on the site, they should be replaced with buildings at another location. Eventually, they argued, the Longmire area should be either devoted exclusively to hotel and campground development or returned to a natural condition. [55]

What was evident in the report by Waterhouse and Davidson was a change in thinking about the proper presentation of government buildings in national parks. In the Park Service's early years, government buildings were given prominent placement. The administrative building at Longmire, for example, faced a curve in the road such that motorists coming from the Nisqually Entrance could not fail to see it as they broke out of the forest and rounded the meadow. Similarly, the administrative building at Sunrise was placed at the end of the plaza, in clear view on the approach through Yakima Park. Government buildings were perhaps never more conspicuous in the national parks than in the 1930s, when the architectural style known as National Park Service Rustic made its mark. By contrast, the Mission 66 development plan for Mount Rainier offered the following commentary on government buildings in the park:

A headquarters development includes no public use facilities. It is the administrative center and the service center for the Park, and includes offices, shops, warehouses, garage and storage facilities, and the residential area for headquarters employees—behind-the-scenes facilities which the visitor seldom needs to see or use. [56]

An unusually sharp exchange on this subject occurred between Davidson and Preston in 1943. It seemed to Davidson that the Park Service was serving the public most effectively when it was serving them unobtrusively. Park visitors should be allowed to indulge in the feeling of driving through an uncrowded, wild, and unencumbered landscape. Davidson wrote, "It is difficult to imagine a more beneficial or desirable use of parks than the opportunity they afford for people to escape from the regimentation of their daily lives into a natural and wide open, unregulated (to every possible intent), and free out-of-doors! Just as far as we MUST infringe on this Utopia, to that extent we lessen the highest service and enjoyment a park can render." [57]

Preston took exception to the implication that the NPS had previously wanted to make itself conspicuous "in order to impress visitors...and regiment all who come within our scope." With regard to buildings, it seemed to Preston that they should always be located wherever there was a public need. "Time and again in my experience this has been one point the landscape people forget. If we are going to construct a building, why not put it where it will be used most effectively?" Preston asked. "If in the interests of the preservation of the natural scene, we have to place it where it is not effective for its intended use, why build it?" [58] Preston, together with his assistant superintendent, chief clerk, chief ranger, and park naturalist, submitted a lengthy report in 1943 that sought to refute the need to move headquarters out of the park; they preferred to expand the facilities at Longmire. [59]

The impact of headquarters development on park resources had to be figured in relation to other factors such as cost efficiency, employee morale, and public safety. But those in favor of moving headquarters out of the park could always insist on the primacy of resource protection. Regional Landscape Architect Sanford Hill underscored this point in a planning report for Mount Rainier in 1946. "Conservation, Protection, and Preservation, must be considered in number one priority in any discussion of the Overall Plan," he wrote. "These responsibilities dictate a conservative approach on all proposed facilities." [60] Eventually this planning principle proved decisive in resolving the question of where park headquarters should be located.

Reckoning with the Threat of a Natural Disaster

The most problematic question involved in the possible relocation of park headquarters was the extent to which Longmire was threatened by natural disaster. The Longmire area straddled the Nisqually River and was built in its flood plain. The Nisqually River had flooded a number of times since the creation of the park. The floods seemed to be correlated with heavy rainfall, but they emanated from the river's glacier source and were sudden, violent, and not well-understood. According to Regional Engineer H.L. Crowley in 1943:

The River is fed by the normal rainfall and the melting glacier. Apparently these sometimes combine to produce surges of water brought about, according to observers, when a series of small lakes form in depressions in the ice and the upper one overflows, cutting a channel in the ice to one lower down. This causes the lower lake to overflow and cut a channel and so on until the series is drained, thus developing a surge such as piled 15 feet or more of debris and rocks on the Nisqually Bridge several years ago. Another cause for the surges has been given as the damming of the River by the moraine which forms a lake. When the dam is topped it washes out and a flood occurs. [61]

During the CCC era, log cribbing and rock revetments were built and maintained to protect Longmire from flooding. But more extensive revetment seemed to be required. Proposed strategies and cost estimates for flood control in the Longmire area varied widely.

One important result of the concern about a natural disaster was to eliminate other potential administrative sites—the Kautz Creek site and the Nisqually Entrance site—from consideration. They, too, were situated on the Nisqually River and would be threatened by natural disaster. The Kautz Creek flood in 1947 made the point most forceably, inundating an area that had been suggested for park headquarters only four years before. This left the site near Ashford, if in fact Longmire was to be abandoned because of the flood hazard. [62]

The threat of a natural disaster played well before Congress, too. Like the problem of snowloads, it was a condition unique to the area that demanded special consideration. In the brief congressional debates that preceded the Act of Congress of June 27, 1960, authorizing the Department of the Interior to acquire the Tahoma Woods administrative site for Mount Rainier National Park headquarters, the flood hazard at Longmire figured prominently.

ROADS AND TRAILS

When the NPS initially spelled out Mission 66 for Mount Rainier, the development plan included an estimated $4,265,000, or 42 percent of the estimated total investment, for construction and improvement of roads. The main projects were (1) completion of the Stevens Canyon Road, (2) construction of the new winter access road to Paradise (now called the Paradise Loop Road, because it allowed traffic to flow in a loop through Paradise Valley during the summer), and (3) improvement of the Westside and Mowich Lake roads. This constituted the third and final spate of road-building in the development of the park.

Road development was central to the basic thrust of Mission 66, which aimed to head off overcrowding by dispersing visitors more widely around the park. Most day-use visitors were highly mobile, dependent on their cars, and essentially roadbound. NPS planners thought that by modernizing the park infrastructure to suit the day-use visitor, they could keep traffic flowing, reduce the feeling of crowding, and thereby increase the park's visitor carrying capacity. To this end, the driving tour would be encouraged; the car, the road, and the wayside exhibit would increasingly frame the common visitor experience at Mount Rainier. The Park Service's March 1956 press release on Mission 66 for Mount Rainier said as much when it announced that "numerous scenic overlooks, picnic areas and campgrounds provided in the 10-year program will encourage the dispersal of visitors over a wide area and [will] reduce the damaging overcrowding at Paradise and other popular centers within the park." [63] A memo on Mission 66 dated August 31, 1956, expressed even greater enthusiasm about the potential for roads to disperse the public: "This entire road system will be treated in such a way that the visitor will enjoy numerous scenic, recreational, and interpretive experiences as he drives through the park." [64]

Stevens Canyon Road

Although the completion of the Eastside Road in 1940 had finally given the park a through-road, few park visitors used the road connections with U.S. Highway 410 and U.S. 12 to make a grand loop around Mount Rainier. To fulfill the longstanding idea of an around- the-mountain auto trip it was necessary to tighten the loop. That was the main purpose of the Stevens Canyon Road. Motorists would be able to make a complete trip around the mountain leaving Seattle or Tacoma in the morning and returning the same day. A secondary purpose was to connect the two main centers of the park at Paradise and Sunrise in order to improve administrative efficiency.

Local business interests saw the completion of the Stevens Canyon Road as a potential boon. If it were possible to explore both sides of the park without having to drive out of the park, they reasoned, then Mount Rainier might attract more of the kind of destination tourists that the park's boosters had always desired to attract. For the Rainier National Park Advisory Board's Elmun R. Fetterolf, it seemed that "the completion of this highway will do much to hold visitors within the park area." [65] The RNPC was skeptical about what the through-road would do for its hotel business, but it entertained high hopes for a lucrative around-the mountain transportation service. Martin Kilian, owner and operator of the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs concession, believed that the completion of the Stevens Canyon Road would bring substantially more business to the southeast corner of the park. [66]

|

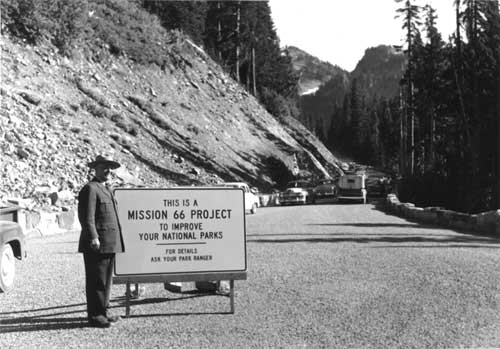

| Completion of the Stevens Canyon Road was the most anticipated Mission 66 project for Mount Rainier. This is opening day, September 4, 1957. (Richard Neal photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

No one could predict with any certainty how the completion of the Stevens Canyon Road would affect visitor use. Some park planners anticipated that the Stevens Canyon Road would entice a considerable percentage of day-use visitors to enter the park from one side and exit from the other, thereby spreading use more evenly around the park. Others thought that an overnight center in the lower part of Stevens Canyon would be needed to draw people away from Paradise and Sunrise, or cautioned that the new road might attract large numbers for the first few years and then fall into disuse. [67] The Mission 66 committee optimistically predicted that completion of the Stevens Canyon Road would "revolutionize the present travel pattern within the park." [68] Skeptics predicted—most accurately as it turned out—that the vast majority of day-use visitors would continue to drive to either Paradise or Sunrise and return by the same road.

Construction of the Stevens Canyon Road had begun in 1931, with most of the right-of-way reaching completion by World War II. After an eight-year hiatus, construction of the Stevens Canyon Road resumed in 1950. Between 1950 and 1952, contractors built bridges at the Muddy Fork and Nickel Creek, viaducts below Stevens Creek, a tunnel near the Muddy Fork, and masonry retaining walls and parapets. By the summer of 1952, the road was passable to trucks and was used to a limited extent for administrative purposes. [69] Mission 66 provided the last burst of funds to bring the project to completion, 25 years after it was begun. By then, the Stevens Canyon Road was no longer the biggest item in the park's road construction program; this honor belonged to the new winter road from Narada Falls to Paradise. But the long anticipated road had the highest public profile. The road was opened to the public in the summer of 1957.

Paradise Loop Road and Parking

Mission 66 for Mount Rainier included construction of a new road from Narada Falls to Paradise. The road began at Marmot Point and ascended the mountain by switchbacks to the relatively level ground known as Barn Flat which stretched to the south of the Paradise Lodge. The road had a dual purpose: in summer, it would form a loop with the existing road through Paradise Valley, easing weekend traffic congestion; in winter, it would provide a safer route to Paradise, obviating the need to use the avalanche-prone section of road at the lower end of Paradise Valley.

The Paradise area had always been plagued by a shortage of parking, and it was clear that the new road would not alleviate this situation by itself; additional parking space must be developed, too. Mission 66 aimed to double or triple the amount of parking. The main question was whether to put the additional parking space underground, on the surface, or in a multi-level enclosed structure. The architectural model for this last option was the new, eleven-story Downtown Center Garage in San Francisco. To build a large parking garage in a national park was a novel concept and certainly pointed up the dimension of the parking problem. Although the plans for underground or multi-level parking were eventually rejected in favor of additional parking space on the surface, it is worth reviewing the arguments for and against such a development.

The main argument in favor of underground or multi-level parking was that either one would take up less ground surface and reduce the amount of scarring of the landscape. The plan for underground parking envisioned two or three sublevel floors of parking underneath a new day-use building; it would be the least obtrusive, visually. The plan for an above-ground parking garage envisioned a concrete structure similar to the one in San Francisco, but with exterior walls made of reinforced concrete in order to brace the building against inclement weather and snowloads. Another advantage to both of these designs was the fact that they would obviate the need for snowplowing the existing parking lot or any additional parking lots. [70]

The disadvantages varied between the underground and above-ground parking garages. The main drawback of the underground parking garage was that it was thought to be prohibitively expensive—perhaps $3 million (in addition to the cost of the day-use building above it). The above-ground parking garage would be expensive, too—perhaps $2,250,000 for 1,200 parking stalls. But it had the further disadvantage that it would be unsightly and unappealing to use. The aesthetics of parking would be especially important during the summer, when visitors would have a choice of parking in the open air near the Paradise Inn or driving into a parking structure. Certainly they would prefer the former. If the government were to build a parking garage and try to recover some of the cost by charging parking fees, it would not do to have the parking garage serve as overflow parking, standing empty and not drawing any revenue most of the time. [71]

Westside and Mowich Lake Roads

Mission 66 for Mount Rainier provided the clearest statement of policy on road development for the west side in twenty years. It can be viewed as a turning point for that section of the park. The Westside and Mowich Lake roads would be improved, but they would not be extended or joined together as originally intended. The area in between the ends of these two roads would be retained in a wilderness condition. The Park Service' s emphasis on wilderness values on the west side was not seriously contested until many years later, when road and campground closures brought protests from some user groups.

It will be recalled that the original plan was for the Westside Road to connect with the Carbon River Road, forming a leg in the eventual around-the-mountain road. Later, the steep topography around Ipsut Pass convinced NPS officials to modify the plan such that the Westside Road would exit the park near Mowich Lake. Rather than forming a leg in an around-the-mountain road, the Westside Road would create a spectacular loop drive intersecting the west side of the park. To get this started, Pierce County was encouraged to build a road to the park boundary west of Mowich Lake, and the NPS would complete the Westside Road via the North Puyallup Canyon, Sunset Park, the Mowich River, and Mowich Lake. In 1931, road crews completed clearing work on the right-of-way approximately half the distance from the North Puyallup River to Sunset Park; in 1932, the road was opened to cars as far as the North Puyallup River. At the other end of the road, meanwhile, the county had a passable road completed to the park boundary by 1933, when the new park entrance was dedicated in honor of Dr. William Tolmie's visit to the area exactly one hundred years earlier. But then people began to express doubts about the project.

Landscape Architect Ernest A. Davidson offered the most forceful criticism of the Westside Road in 1934. He wrote,

Surely the most rabid road enthusiast will agree that highways enter a satisfactory number of spectacular canyons about Mt. Rainier when he finds that roads and highways enter Nisqually Canyon, Stevens Canyon, Cowlitz Canyon, Ohanapecosh Canyon, White River Canyon, Carbon River Canyon, Tahoma Creek Canyon, South Puyallup Canyon and North Puyallup Canyon... .This has carried highway development far enough for a small park. [72]

Others expressed similar concerns, and road development on the west side was all but suspended. On September 9, 1938, Secretary of the Interior Ickes advised that no further road construction would be authorized in Mount Rainier after the completion of the Stevens Canyon Road, and Director Cammerer had the master plan revised accordingly. [73]

Responding to public pressure after World War II, Superintendent Preston and Landscape Architect Vint proposed to complete the six miles of road from the park boundary to Mowich Lake so that Pierce County would have something to show for its investment. [74] Regional Director Tomlinson argued that this would only excite more demand—demand for completion of the Westside Road as envisioned earlier, demand for overnight accommodations at Mowich Lake, and possibly even demand for development of another ski area at Spray Park. In short, Tomlinson visualized all the difficulties of Paradise being duplicated on the northwest side of the mountain.

The surfacing of the road will head us squarely into all the difficulties of a dead-end road which would open one of the choice areas of the park nearer to centers of population than any of the other developed areas of the park. Not only will pressure develop for overnight accommodations, but there will be increasing demand for facilities for winter use of the area. [75]

Tomlinson won his point, and the road was not opened to Mowich Lake until 1955. By then, it was evident that there would be no serious pressure for overnight accommodations or ski facilities in that area.

Mission 66 provided funds for repairs and resurfacing of the whole length of the Westside Road.

Trails

Park staff predicted in 1955 that backcountry use would increase over the next ten years but to a lesser extent than total visitation. [76] Citing the fact that the park already had 290 miles of trails, Mission 66 for Mount Rainier gave trail development low priority. The Mission 66 development plan did include two major trail projects, however.

The first trail project was to build a new trail between Paradise and Indian Bar. The trail would replace sections of the Wonderland Trail which had been obliterated by the Stevens Canyon Road. Some wanted a highline route along Stevens Ridge. The highline route was rejected, however, which left this southern segment of the Wonderland Trail within sight and sound of automobile traffic on the Stevens Canyon Road. [77]

The second trail project, called the Tatoosh Trail, was intended to connect the Pinnacle Peak Trail and the Eagle Peak Trail. Starting at the saddle of Pinnacle Peak, the trail was to traverse along the crest of the Tatoosh Range to the shoulder of Eagle Peak, providing a spectacular alternative route between Reflection Lake and Longmire. (The existing route paralleled the road except where it went up the lower Paradise River Valley, below Ricksecker Point to Narada Falls.) For reasons that remain unclear, the Tatoosh Trail was never built.

Taken together, these two projects appear to have been aimed at mitigating the effects of the Stevens Canyon Road on wilderness use. The Mountaineers had expressed concerns about the completion of that road. Had the two trails been built, they would have given Wonderland Trail hikers a spectacular highline route all the way from Longmire to Summerland, with only the single road crossing at Reflection Lakes. Instead, with neither a trail along the crest of the Tatoosh Range nor a trail over Stevens Ridge, hikers of the Wonderland Trail had no alternative but to take the old Caner Falls Trail from Longmire to Reflection Lakes and the new Stevens Canyon Trail from Reflection Lakes to Box Canyon. From the standpoint of the around-the-mountain hiker, the south side segment of the Wonderland Trail left much to be desired compared to the west, north, and east sides after the opening of the Stevens Canyon Road.

CAMPGROUNDS AND PICNIC AREAS

Mission 66 for Mount Rainier included plans to develop 1,200 new camping and picnic sites, or nearly four times what the park already had. The goal was to be able to accommodate 3,500 additional visitors per day by 1966. Two key components of the plan were to separate day use and overnight use areas, and to locate the latter almost entirely at low elevations. As in the case of road development, NPS planners expressed optimism that new campgrounds and picnic areas could disperse use more widely through the park. These developments would "enable the Park to absorb two or three times its present travel, satisfy more fully the needs of all visitors, and do so without further encroachment upon or impairment of the primary scenic areas." [78]

In 1956, the park had eight campgrounds and nine picnic areas, some of them quite small and primitive. There were three campgrounds at high elevations (one at Paradise and two at Yakima Park), and five at low elevations (Longmire, Ohanapecosh, White River, Ipsut Creek, and Tahoma Creek). The Mission 66 development plan proposed to expand the five campgrounds at low elevation, while keeping the campgrounds at Paradise and Yakima Park small with a view to eliminating them altogether eventually. It also proposed new campgrounds and picnic areas at Sunshine Point, Mowich Lake, and Klickitat Creek, and new picnic areas at Stevens Creek, Box Canyon, Cayuse Pass, and Tipsoo Lake. [79]

This scheme was modified somewhat in the course of the ten-year program. A new campground and picnic area were laid out at Paradise in the meadow known as Barn Flat, and the old campground was abandoned. The old CCC-built campground and picnic area at Sunrise (near Shadow Lake) was rehabilitated and the smaller campground beside the visitor center was converted to a picnic area. At Ohanapecosh, a steel bridge was built across the Ohanapecosh River and several new loops were added to the campground. Additional loops were added to the south and east sides of the Longmire campground, and the Ipsut Creek and White River campgrounds were enlarged as planned. Small campgrounds were established at Mowich Lake and Sunshine Point. Plans for the campground and picnic area at Klickitat Creek were abandoned, and instead a large campground and picnic area was built at Cougar Rock, two miles up the road from Longmire. [80]

|

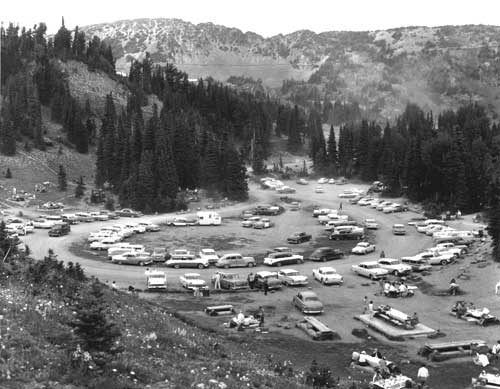

| Campground and picnic area at Sunrise, July 1960. Mission 66 called for the development of 1,200 new camping and picnicking sites mostly at lower elevations in order to disperse visitor use and alleviate crowded conditions such as seen here. (J. Boucher photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

MUSEUMS AND WAYSIDES

The Mission 66 development plan sought to integrate all areas of park development into a unified whole. As part of that plan, the Mission 66 committee crafted an interpretive program for the park that would serve the day visitor better and would assist with the overall goal of spreading use more evenly throughout the park. The interpretive program had two main elements: a decentralized museum plan that divided the park story between four museums at Longmire, Paradise, Sunrise, and Ohanapecosh; and an emphasis on wayside exhibits that facilitated self-guided automobile tours of the park. Mission 66 was a turning point in the evolution of Mount Rainier's interpretive program both in terms of design and funding.

Like other elements of the Mission 66 development plan, the interpretive program sought to take into account changes in the visitor use pattern since World War II. Statistics compiled on the number of visitor "contacts" made by the interpretive program from 1940 to 1956 demonstrated the declining effectiveness of the interpretive program in the face of this changing pattern of visitor use:

Visitor Contacts by Interpretive Program, 1940-1956

| Travel Year | Total Visitors |

Percent of Visitors Contacted by Interpretive Program |

| 1940 | 456,637 | 70.6 |

| 1941 | 476,776 | 59.4 |

| 1942 | 343,575 | 56.1 |

| 1943 | 124,474 | 73.2 |

| 1944 | 135,277 | 50.4 |

| 1945 | 304,227 | 69.1 |

| 1946 | 470,903 | 65.2 |

| 1947 | 519,698 | 58.8 |

| 1948 | 570,053 | 69.4 |

| 1949 | 584,004 | 42.9 |

| 1950 | 573,685 | 72.1 |

| 1951 | 873,877 | 38.2 |

| 1952 | 877,388 | 46.7 |

| 1953 | 768,015 | 60.0 |

| 1954 | 794,955 | 61.2 |

| 1955 | 839,214 | 48.7 |

| 1956 | 850,747 | 45.3 |

Not only was total visitation rising in proportion to the number of naturalists on the park staff, but the number of local visitors was increasing in proportion to the number of out-of state visitors. It was the out-of-state visitors who were most likely to stay overnight in the park, attend interpretive programs, and visit the park museums. Local visitors were most inclined to come only for the day and make their own way around the park. Local visitors might take advantage of wayside exhibits or, at most, stop at a museum. Wayside exhibits and museums seemed to be the best means of serving this group.

Another important feature of the Mission 66 development program was the "visitor center." The idea of placing visitor information, park interpretive exhibits, and day-use facilities together in one building and encouraging park visitors to make the visitor center their first stop in the park was a significant innovation. The visitor center was an effective tool for managing visitor circulation and use, and other federal and state agencies and even private enterprises soon adopted it. [81] By the end of the Mission 66 era, Mount Rainier had two new visitor centers at Ohanapecosh and Paradise.

Museum Development

Mission 66 for Mount Rainier called for the development of three main visitor centers at Paradise, Sunrise, and Longmire, and three smaller establishments at Ohanapecosh, Crystal Creek, and on the south bank of the Nisqually River by Skate Creek Road. Of the six, only the first four would have museums. The latter two sites, located outside the park boundary, were later dropped from the plan. [82]

Anticipating that the typical day use visitor would have a very limited amount of time to peruse the museum exhibits, the plan called for a select number of exhibits in each museum that would focus on one aspect of the Mount Rainier story. At Paradise, the museum exhibits would emphasize the glacier story of Mount Rainier. The visitor center at Sunrise would present the story of volcanism at Mount Rainier. The Ohanapecosh visitor center would give the story of the lowland forests. At Longmire, the museum exhibits would emphasize the national park idea and local history. [83]