|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART ONE: THE CULTURAL SETTING |

II. MOUNT RAINIER AND AMERICAN SETTLEMENT

INTRODUCTION

National park managers have long understood that land uses outside parks, indeed long distances from parks, can produce environmental changes inside park boundaries. There are so many interrelationships between one kind of land use and another that no mere political boundaries can completely insulate an area from the environmental changes occurring around it. Wildlife populations, fire ecology, scenic vistas, and even air quality are affected by changes in the land around Mount Rainier National Park. Moreover, major land uses such as logging, the construction of the transcontinental railroads, and urbanization have shaped the political environment of Washington state. State and local politics, too, have had an important bearing on how the park was administered.

The cultural setting of western Washington is integral to Mount Rainier National Park's historical development. This section focuses on three salient features of this cultural setting: the timber industry, transportation links, and urbanization. The timber industry became the leading sector in the regional economy as early as the 1850s and remained so well into the twentieth century. Transcontinental railroads exerted enormous influence on the area's development in the 1880s and after. The railroads in turn created the necessary conditions for the rise of Seattle and Tacoma in the last twenty years of the nineteenth century. The cities did more than any other factor to reshape people's attitudes about the wilderness and the way they used it.

THE TIMBER INDUSTRY

Early visitors to western Washington found that its wet climate had produced a lush growth of Douglas fir, hemlock, spruce, and cedar, from the slopes of the Cascades to the very edge of Puget Sound. Early lumbermen recognized the region's economic potential as soon as the California gold rush created a market for lumber on the west coast. The industry began on the shores of Puget Sound in the early 1850s with California-owned sawmills erected at Port Ludlow, Port Blakely and Port Madison, and with a New England-owned sawmill built at Port Gamble. The new companies soon expanded on their coastal trade by finding markets in Hawaii and around the Pacific Rim. Approximately eighty percent of investment in Washington Territory's economy in the 1860s and 1870s went into lumbering. [1] Nevertheless, without railroad connections to eastern markets the industry remained small in comparison to lumbering operations elsewhere in the nation. Before the coming of the railroads, one historian has written, "northwest lumber [was] something like Robinson Crusoe's pile of gold; there was lots of it but it was worth very little since there was so little opportunity to use it." [2]

The first major change in Washington's timber industry occurred with the completion of the transcontinental Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883. The railroad stimulated settlement, created local markets for lumber, and linked the Pacific Northwest to markets back east. These changes also attracted new investment capital to the region, particularly from Midwestern lumber barons who faced dwindling supplies of timber for their operations in the Great Lakes States. They found Washington lands not only more heavily timbered per acre than what they were used to, but far cheaper as well. Making often fraudulent use of the Timber and Stone Act of 1878, lumber companies acquired hundreds of thousands of acres of timberland from the public domain in the 1880s. The land grab by these lumber companies was an important spur to the creation of Washington's first forest reserves in the 1890s. [3]

The center of lumbering in Washington shifted in these years from the upper Puget Sound region southward to Tacoma and westward to Grays Harbor. Lumber interests built numerous branch railroads inland to exploit new timberlands. They were aided further by the introduction of the steam-powered donkey engine which could move logs farther and faster than the old ox-team and skid road method of logging. While the old mill ports continued to handle the waterborne lumber trade, these mostly California-owned companies found themselves at a competitive disadvantage with the new lumber companies which used the railroads to reach much wider markets. [4]

A second major change in Washington's lumber industry developed after the turn of the century as lumbermen began coming to grips with the fact that the state's timber supply was not limitless. The larger companies began to seek a change from the "cut-and-run" logging operations of the nineteenth century to less wasteful methods of timber harvesting based largely on economy of scale. Symbolic of this transition was Midwest timber magnate Frederick Weyerhaeuser's purchase in 1900 of 900,000 acres of Washington timberland from the Northern Pacific's land grant holdings. In three and a half years Weyerhaeuser increased the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company's interests in western Washington to 1.3 million acres. These huge holdings by one of the nation's leading timber barons showed that the center of the timber industry had shifted from the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest. At the same time, lumbermen began to work in cooperation with government foresters to address what were seen as the two biggest imperatives for improved efficiency in the timber industry: protection of forests from wildfire and reform of the property tax system. To this end, lumbermen and foresters formed the Washington Forest Fire Association in 1908 and the Western Forestry and Conservation Association in 1909, and supported the establishment of a Forestry School at the University of Washington in 1907. [5]

Efficiency was also the watchword of the new conservation movement. Led by Gifford Pinchot, forestry "professionals" sought to manage forests as though they were crops, harvesting trees when they were "ripe," protecting stands against fire and disease, guarding against deforestation and soil erosion. Government forestry initially focused on research and conceived of its role as an advisory one; after the turn of the century, however, the Forestry Bureau (later the U.S. Forest Service) began to concern itself primarily with the management of forest reserves (national forests). In Washington, as elsewhere in the West, leaders in the timber industry generally supported conservation as part of their drive to resolve problems of overcompetition and supply. Opposition to the forest reserves came mainly from smaller concerns as well as agricultural and mining interests. The groundswell of suspicion by westerners toward federal control of resources reached a peak during the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt, in the first decade after Mount Rainier National Park was established.

All of the land included in the park today was previously set aside as forest reserve or national forest land. The Pacific Forest Reserve, proclaimed on February 20, 1893, formed roughly a square thirty-five miles on a side, with the summit of Mount Rainier on its western edge. A subsequent presidential proclamation on February 22, 1897 changed the name of the reserve to the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve and greatly enlarged its boundaries to the west and south. [6] By the time Mount Rainier National Park was established in 1899, the timber industry was already shaping western Washington's cultural landscape in ways that reached far beyond the extent of actual logging operations. Forest lands throughout the Cascade Mountains were being surveyed, purchased, taxed, protected from fire, and placed in reserves for future logging operations and for watershed protection. These myriad forest activities created a political and economic climate which continued to affect land use around and even inside the national park after it was established.

THE RAILROADS

Railroads shaped the cultural setting of Mount Rainier in a very different way than the timber industry. Their primary significance was in binding the Pacific Northwest more closely to the national economy. They not only brought a flood of new settlers to Washington and carried Washington's products to eastern markets, but their advent encouraged an influx of investment capital into the Pacific Northwest as well. The railroads themselves required great concentrations of capital; consequently, the railroad companies wielded enormous political and economic power. The railroads were engines of economic growth in their own right, consuming locally-produced timber and coal and employing labor in railroad construction. [7] They even had the ability, through their popular advertising posters and brochures, to mold public attitudes toward the national parks. [8] Finally, branch lines affected land use and settlement patterns in the vicinity of Mount Rainier.

Washington's railroad history began in 1853, when the territory's first governor, Isaac I. Stevens, journeyed west to take up his new post in Olympia. Stevens actually wore three hats when he came west: besides governor, he was Superintendent of Indian Affairs and leader of the survey of the northern route for a transcontinental railroad. Stevens' role in making treaties with the Indians has been noted; his transcontinental railroad survey was one of four which Congress authorized with a view to binding the far western territories to the nation and improving commercial access to Asia. Due to growing sectional differences between North and South, however, the federal government delayed action on the transcontinental railroad schemes until the Civil War. Congress then passed a law which chartered the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific (1862) and the Northern Pacific (1864), the latter to follow the approximate route of the Stevens survey. [9]

The government provided the Northern Pacific with an enormous land grant, the largest of any land-grant railroad, with which to pay for construction. The grant consisted of a strip of land 200 feet wide as a right of way, plus a swath of alternate sections along the railroad's entire length, ten miles to either side of the railroad in the states and twenty miles in the territories. As the original charter provided that the railroad would cross the Cascade Range by way of the Yakima River, the Northern Pacific's grant covered the area of the future Mount Rainier National Park. The company, however, could not claim title to the land until it built the railroad and surveyed the lands, so to help the company out of financial straits Congress modified the charter such that the railroad could mortgage its land grant beforehand. [10] When the Northern Pacific went bankrupt in 1873 without having completed the line, Washington residents demanded that the grant be rescinded so that the lands would be open for other uses. But the Northern Pacific retained these lands, and popular resentment toward the railroad and the land grant continued to be very strong for many years. [11]

The coming of the Northern Pacific Railroad spurred an intense competition between Tacoma and Seattle to be chosen for the terminal city. Seattle lost. In 1870, the company modified its plan so that the main line would follow the Columbia River to Portland, utilizing an existing twenty-mile railroad section belonging to the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, and then go north up the west side of the Cascades to Tacoma, thereby acquiring an additional 2 million acres of timber land along the Columbia and Cowlitz valleys. [12] Though the line from the Columbia River to Tacoma was completed before the company went bankrupt, it still did not link the city by rail to the eastern United States or give Tacoma much assurance that it would become the queen city in western Washington. Seattle fought hard in the 1870s to hold its ground as the most populous settlement on Puget Sound, attempting among other things to build its own railroad over the mountains to eastern Washington using local capital and labor. Both cities had to wait nearly another decade for their long-sought railroad connection to the eastern United States. In 1881 railroad financier Henry Villard brought all the existing railroads in Oregon together with the Northern Pacific and the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company and completed the transcontinental connection through Idaho and Montana two years later.

The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883 began a period of economic boom in Washington state's history. This period was punctuated by the completion of three more transcontinental lines over the next two and a half decades. In the mid-1880s, the Union Pacific constructed a branch from its main transcontinental line known as the Oregon Short Line. This line went from Ogden, Utah through southern Idaho and eastern Oregon to the Columbia River, and made the Union Pacific the second transcontinental to reach the Pacific Northwest. [13] In 1889, railroad magnate James J. Hill inaugurated a plan to construct another transcontinental—the Great Northern—further north, relying on many local feeder lines rather than federal land grants to help finance it. This time Seattle, with the help of its short, pre-existing railroads, secured the prize of western terminal. The railroad's golden spike was driven at Stevens Pass in 1893. [14] In 1909, still one more transcontinental line was built to Puget Sound: the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul (known as the Milwaukee Road) completed the only electrified line from the Midwest to Seattle. Later these four transcontinental railroads—Northern Pacific, Union Pacific, Great Northern, and the Milwaukee Road—would figure prominently as potential financiers in the development of Mount Rainier National Park.

Branch railroads were almost as important as the transcontinentals in shaping the cultural landscape around Mount Rainier. Branch lines linked Seattle and Tacoma to coal fields in the Cascade foothills, stimulated agricultural development, and determined the location of outlying farm communities. The rail connections between the Puget Sound cities and the coal fields were essential to the development of western Washington's coal mines, which supplied the steamships engaged in the timber industry. Seattle businessmen were particularly aggressive in getting rail connections to the coal beds, for it was largely coal exports which enabled the small city of about 1,000 residents to maintain its lead over Tacoma in population growth during the late 1870s and early 1880s. The development of the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, built as far as Renton in the 1870s, gave the city an early advantage over Tacoma in attracting the coal trade, while the Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad pushed from Renton to the Black Diamond coal mines in 1882 and into the Cedar River Valley in 1884. [15]

Further south and nearer Mount Rainier, Northern Pacific surveyors discovered coal beds in the Carbon River drainage in 1875 while surveying the Northern Pacific's eventual route over the Cascades via Stampede Pass. Years before it completed its main line over the Cascades, the Northern Pacific built a branch line from Tacoma through South Prairie to these coal beds, giving rise to the mining town of Wilkeson at the end of the line. As the Northern Pacific began construction of its main line over the Cascades in 1884-85, it stimulated interest in the timber resources on the plateau between the White and Puyallup rivers and the clearing of bottomlands for agriculture. New towns sprang up along the railroad. Enumclaw was platted between 1885 and 1890 and had a population of nearly 500 by 1900. [16] The Orting townsite was filed in 1887, while the platting of South Prairie and Buckley followed the next year. The former enjoyed steady growth as the Puyallup Valley was turned into farmland; the latter thrived as fruit growers moved into the White River Valley. [17]

Both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road took an interest in developing branch lines to tap the timber and mineral resources in the upper Nisqually and Cowlitz valleys. In 1890, the Milwaukee Road incorporated the Puget Sound, Mt. Tacoma and Eastern Railroad Company, whose tracks were to run southeast from Tacoma past Lake Kapowsin to the Nisqually River, and then up that valley toward Mount Rainier. As the depression of 1893 delayed construction, the initiative temporarily passed to the Northern Pacific, who sold an option on its extensive timber holdings in the upper Nisqually and Cowlitz valleys to the St. Paul and Tacoma Lumber Company in exchange for that company's promise to build a line into the area. By 1896, this railroad, the Tacoma, Orting and Southeastern Railroad, had reached the western shore of Lake Kapowsin but was running into financial difficulty. The Northern Pacific, more interested in selling its timber holdings than gaining the additional traffic over its system, backed the Puget Sound, Mt. Tacoma and Eastern Railroad instead. [18] In 1902, the so-called Tacoma and Eastern reached the new town of Eatonville, and two years later reached as far as Ashford, seven miles from the new national park boundary. [19]

These railroads were built primarily to exploit the timber and coal resources in the Cascade foothills rather than to profit from passenger traffic to Mount Rainier. However, the railroads were always looking for additional sources of income for their lines and they were certainly not blind to the possibility of developing a lucrative tourist business, as the Tacoma and Eastern's subsequent investments in Mount Rainier National Park would demonstrate. After 1899, the Northern Pacific would repeatedly consider the possibility of extending its line from Wilkeson into the northwest corner of the park with this purpose in view. Yet, defying expectations, Mount Rainier National Park never developed as close a relationship to the major railroad companies as some other western national parks did. The simple explanation for this is that tourism was incidental to the area railroads' main objectives, which were timber and coal. More importantly, however, the relationship between the railroads and this national park was tempered by the proximity of Seattle and Tacoma. These two cities would prove to be the real driving forces of Mount Rainier National Park's development, providing local initiative for road and hotel construction and a concentrated population of park users with an effective political voice.

THE CITIES

Surpassing the influence of both Washington's timber industry and the railroads, the growth of a major metropolitan area on Puget Sound became the most important feature of Mount Rainier National Park's cultural setting. The cities of Seattle and Tacoma provided much of the stimulus for the establishment of Mount Rainier National Park and much of the capital for its development. The cities' chambers of commerce boosted the national park and involved themselves deeply in its administration, both through the state's senators and congressmen and through their self-appointed Rainier National Park Advisory Board. Residents of Seattle and Tacoma accounted for a large proportion of the park's visitors, many of whom found a voice for influencing park administration through outing clubs like The Mountaineers. The proximity of Mount Rainier National Park to the two cities made the park increasingly oriented to weekend and day use by automobilists. Arguably, the relationship of this park to its nearest cities was more pronounced than that of any other national park in the United States. [20]

|

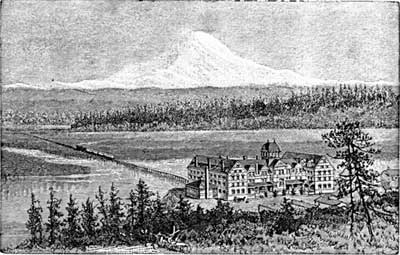

| Puget Sound cities made Mount Rainier into an icon. In this 1878 etching the Northern Pacific Railway Company 's terminal city of Tacoma and Mount Rainier appear bound together by destiny. Only the tideflats separate the city and the wilderness. |

Even before the establishment of Mount Rainier National Park, citizens of Seattle and Tacoma laid claim to the mountain as a symbol of the good life in the Pacific Northwest. The beauty of Puget Sound's forests, lakes, tidewater, and mountains was a source of civic pride, and the image of Mount Rainier looming on the horizon beyond Seattle's Lake Washington or Tacoma's Commencement Bay was the most commonly used symbol of that pride. This is evident from the booster literature of the period. Boosters were the advertising professionals of their day; they were sensitive to public tastes and attitudes. Boosters for Seattle and Tacoma, of which there was no shortage in the late nineteenth century, were probably not being unrealistic when they perceived western Washington's scenery as a selling point for attracting immigrants, investment capital, and tourists to their cities. But Seattle's and Tacoma's boosters were not simply describing the way things were; they were crafting an image of their respective cities which would have far-reaching consequences for the development of Mount Rainier National Park.

In describing Mount Rainier's natural beauty, boosters generally implied that the mountain had a tonic effect on the cities' residents even as they viewed it from Seattle or Tacoma. One offering by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce described the city's setting as "magnificent," with the Cascades visible to the east and the Olympics to the west, while to the south, "even these grand features are dwarfed by the stupendous Mt. Rainier." [21] A souvenir edition by the Seattle Daily Times in 1900 asserted that Puget Sound possessed greater scenic attractions than any place in the country, "and it is very much doubted if any other spot on earth can excel it." [22]Crawford & Conover Publishers averred, "The Scenery on Puget Sound, and especially that in the immediate neighborhood of Seattle, is truly grand. This adds not a little to the pleasure of living in this favored region." [23] To drive home the connection between the Puget Sound cities and the mountain scenery, these works frequently used a view of Mount Rainier for their frontispiece. [24] Scenic appreciation became such a motif in the booster literature on Seattle and Tacoma that it eventually provoked the otherwise incomprehensible book title, You Still Can't Eat Mt. Rainier! [25]

Seattle's appropriation of the mountain's image reached a climax with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909. The city's boosters intended to demonstrate that Seattle had arrived as one of the great cities of the nation, and the AYP fair featured exhibitions on Alaska and the Orient, underscoring Seattle's importance as a port city. Seattle invested $10 million on the buildings and grounds near Lake Washington, on what would become the University of Washington campus, and advertisements projected an image of a sophisticated "Ivory City" in a land of Eden.

|

| Like Tacoma, Seattle tried to incorporate Mount Rainier into its own image. In 1909 Seattle's Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition featured a view of Mount Rainier down Rainier Vista. Note that this is a composite photograph in which the mountain and forest appear closer to the city than they really are. (Frank Nowell photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. Nowell 1040A.) |

On every hand stretch green lawns, shaded walks and glowing flower beds. In every nook and corner the cactus dahlias, rhododendrons and flowering shrubs of the big woods of Washington are massed in profusion. Down Rainier Vista, across the sparkling blue waters of Lake Washington, majestic Mt. Rainier raises her massive head among the clouds, and over all, the blue sky and balmy air of summer on the Puget Sound make of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition a veritable fairyland. [26]

Rainier Vista formed the main axis of the fairgrounds, so that the view of Mount Rainier was framed by beautiful buildings down either side of the promenade and the play of Geyser Fountain in the center foreground. This was the scene around which the whole complex was oriented.

While the 1890s and 1900s marked the heyday of Seattle's identification with Mount Rainier, Tacomans had been trying to lay claim to the mountain's symbolism for much longer. Indeed, their city took the name Tacoma from the Indian word for "snow peak," which it was said the Indians applied specifically to Mount Rainier, and much of the boosters' efforts to identify their city with Mount Rainier focused on getting the name of the mountain officially changed to Mount Tacoma. The effort dated from as early as 1873, though it reached fever pitch on three subsequent occasions: in 1890 and 1917, when it was twice brought before the United States Geographic Board, and in 1925, when it briefly claimed the attention of Congress. The desire of Tacomans to capitalize on this name association was, of course, the real basis for the feud over the mountain's name, even though the debate focused mainly on the authenticity of the Indian name "Tacoma" and the allegedly unpatriotic and prosaic flavor of the official name "Rainier." [27]

According to testimony given to the United States Geographic Board in 1917, the founder of Tacoma, one Morton M. McCarver, decided to change the name of his new townsite from Commencement City to Tacoma on the advice of a visitor who had just read Theodore Winthrop's Canoe and Saddle and had been struck by Winthrop's use of the Indian name "Tacoma" for Mount Rainier. [28] McCarver's whole object in founding Tacoma was to select a townsite which the Northern Pacific Railroad would choose as its western terminus, and naming his town for the region's most prominent landmark was shrewd. When the Northern Pacific did choose Tacoma, it too saw the advantage of linking the mountain to the city by name association. In 1883, the company announced in its Northwest Magazine:

The Indian name Tacoma will hereafter be used in the.. .publications of the Northern Pacific Railroad.. .instead of Rainier, which the English Captain Vancouver gave to this magnificent peak when he explored the waters of Puget Sound in the last century. [29]

Ironically, the railroad's decision probably did more than anything else to perpetuate the use of "Mount Tacoma" even while it gave opponents their strongest evidence that the name change was a promotional scheme. [30]

The controversy over the mountain's name revealed how both Puget Sound cities, through their symbolic use of the mountain's image, were trying to claim a kind of proprietary interest in it. It was symptomatic of the two cities' keen competition not only to become the most well-known city in the Pacific Northwest, but also to gain the best railroad connections, capture the most hinterland, and even (as will be seen in later chapters) secure the best access roads to Mount Rainier. Mount Rainier historian Arthur D. Martinson has written, "in hindsight, it seems strange, perhaps silly, that Seattle and Tacoma spent an inordinate amount of time trying to prove which one owned Mt. Rainier. By the same token, beneath all the flimflam carried out in the newspapers and other publications, the controversy showed some enduring western characteristics: local pride, developmental patterns and, above all, love of landscape." [31] That the name of the mountain could stir such strong partisan feeling for so many years was proof of the boosters' claims that residents of Seattle and Tacoma genuinely cherished their mountain scenery.

The cities' boosters were right about the local inhabitants in another respect: residents of Seattle and Tacoma came to view a trip to the mountain as a favorite destination for country outings, and a climb to its summit as the supreme physical challenge in the region. As late as the 1880s, a trip to the mountain was still almost an expeditionary event, but in the last decade of the nineteenth century it evolved fairly rapidly into a more commonplace activity. By the early twentieth century, the new national park was already experiencing the kind of visitor use pattern that would become more and more pronounced as time went on: the weekend day-trippers had arrived.

Aubrey Haines has told the history of Mount Rainier's pioneer climbs in Mountain Fever (1963), while Dee Molenaar has carried the story into the twentieth century in The Challenge of Rainier (1971). Haines in particular has shown how early climbing expeditions fostered local interest in the mountain and even contributed to the national park movement. Many of the pioneer climbers subsequently played important roles in the campaign to establish the park. Among the first four men to reach the summit—Hazard Stevens and Philemon B. Van Trump in August 1870, and Samuel F. Emmons and A.D. Wilson in October 1870—two of them, Van Trump and Emmons, actively supported the national park campaign in the 1890s. Other pioneer climbers who later worked on behalf of Mount Rainier's preservation included George B. Bayley, who reached the summit with Van Trump and James Longmire in 1883; John Muir and Edward S. Ingraham, who climbed the mountain in 1888; Ernest C. Smith, Fay Fuller, and Eliza R. Scidmore, who publicized their climbs in the early 1890s with writings, lectures, and lantern slide presentations; and Israel C. Russell and Bailey Willis, members of a geological party who were the first to traverse the mountain's summit in 1896.

Mount Rainier climbers formed the Washington Alpine Club in 1891, and its long-lived offspring, The Mountaineers, a few years later. Seattle and Tacoma newspapers followed the climbers' exploits with avid interest. The return of a mountain climbing party was cause for much excitement, as when Ingraham's party of thirteen men and women paraded down the street in Tacoma in 1894, attired in alpine clothing and alpenstocks in hand, looking "like a band of warriors." [32] According to a newspaper account, the Ingraham party drew a crowd of one hundred or more onlookers, and obviously courting the attention, shouted in unison to the crowd:

We are here!

We are here!

Right from the top

Of Mount Rainier!

Such antics seem silly one hundred years later, but they were indicative of the unique cultural setting being formed in the Puget Sound cities. The local mountaineers would play a substantial role in the national park's founding. Some of the individuals in the Ingraham party, for example, would shortly engage in a vigorous debate in the Tacoma Ledger over the source and extent of vandalism at Paradise Park and what ought to be done about it.

Closely akin to the mountain climbing expeditions in this era were the horseback riding, fishing, and camping parties who visited Mount Rainier. As early as the 1880s, the Northern Pacific Railroad found that sufficient demand existed to run excursion cars from Tacoma to Wilkeson, where tourist parties hired horses and guides for trips into the Carbon River highcountry. The best-known guide for the northwest approach to Mount Rainier was George Driver, proprietor of the Valley Hotel in Wilkeson. [33] Meanwhile, on the southwest side of the mountain, Yelm mountain guide and pioneer James Longmire, seeing the future in tourism, found an attractive site by a mineral springs on which to develop his own hotel and spa. In 1884, with the help of some Indians, Longmire cleared a wagon road from Succotash Valley (Ashford) thirteen miles to the springs (Longmire), where he built a rough cabin. [34] In 1887, he filed a mineral claim of twenty acres, and the following year his son Elcaine built a second cabin outside the mineral claim. By 1889, the Longmire family had two bathhouses and some guest cabins completed and were advertising their health spa in the Tacoma newspapers, and by next season they were operating a rustic two-story hotel. [35]

James Longmire looked to the cities not only for business but for help in developing Mount Rainier's tourist potential. In 1891, he addressed a joint meeting of the Washington Alpine Club and the Tacoma Academy of Science, proposing the construction of a road from Kernahan's ranch (Ashford) to Paradise Park (Paradise) "so that a buggy might get up there." [36] Tacomans reacted favorably to the idea. They saw an opportunity to detain in Pierce County a portion of the summer tourists who visited the Puget Sound region each summer. Moreover, it was rumored that King County was sending out surveyors to locate a route from Seattle to Mount Rainier. As one member of the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce remarked to the Board of County Commissioners, "We want to be known the world over as a park city . . . why should we not profit by this—one of our great natural resources?" [37]

As it turned out, Tacomans were not as generous as they initially indicated that they would be, and Longmire built the road with his own money and with a gang of laborers whom he hired locally. Nevertheless, the incident reflected how like-minded Tacoma businessmen and the business-minded Longmire were about the commercial possibilities of scenic appreciation. The idea that Mount Rainier's scenic grandeur was a commodity which could be packaged and sold came to be shared by many people in Tacoma and Seattle in the course of the next century. It would form an important part of the national park's cultural setting.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000